Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cross-border flag for Ireland

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

There is no cross-border flag universally accepted as representing both jurisdictions on the island of Ireland. This can be a problem in contexts where a body organised on an all-island basis needs to be represented by a flag in an international context.

The island is politically divided into the Republic of Ireland (a sovereign state comprising 26 of Ireland's 32 traditional counties) and Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom, comprising the remaining 6 counties in the north-east of Ireland), but all-island organisations are common. Examples include the Catholic Church in Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Church of Ireland, the Gaelic Athletic Association, the Orange Order, Scouting Ireland and the Irish Rugby Football Union.

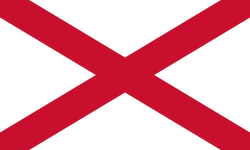

Saint Patrick's Saltire

[edit]The Saint Patrick's Saltire was incorporated into the Union Flag in 1801 by way of the Act of Union 1800 to represent Ireland within the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

The Church of Ireland orders that, apart from the flag of the Anglican Communion, only this saltire may be flown on its church grounds—as opposed to the tricolour, the Union Flag or the former flag of Northern Ireland. This follows the practice of other Anglican churches in England, Scotland, and Wales, which fly the flags of their respective patron saints instead of the Union Flag.[1]

The saltire is also flown by the Catholic St. Patrick's College, Maynooth, on graduation days.

Modified versions have been used formerly by the Irish Rugby Football Union, and currently by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and the Commissioners of Irish Lights.[2]

Irish tricolour

[edit]The tricolour of green, white and orange, the official flag of the Republic of Ireland, was originally intended by nationalists to represent the entire island. When it was first publicly unveiled by Thomas Francis Meagher in Waterford in 1848 he suggested a possible alternative design incorporating the red hand of Ulster:

"If this flag be destined to fan the flames of war, let England behold once more, upon the white centre, the Red Hand that struck her down from the hills of Ulster."[3]

The intended symbolism of unity is rejected by Ulster unionists, as illustrated by an exchange in the House of Commons of Northern Ireland in 1951:[4]

-James McSparran (Nationalist Party): The tricolour is admitted by all nations within the comity of nations to be the national flag of Ireland.

-Honorable members: No.

-McSparran: We are having interruptions already. It is the national flag of the Irish Republic.

-William May (Ulster Unionist Party): That is better.

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) flies this flag at matches regardless of whether either or both teams are from Northern Ireland. It is also used for the Ireland international rules football team, selected by the GAA on an all-island basis.

The Golfing Union of Ireland covers the whole island and competes under the tricolour in international events such as the World Cup, Alfred Dunhill Cup and the Eisenhower Trophy.[5]

Four Provinces flag

[edit]The Four Provinces Flag of Ireland is a quartering of the arms of the four provinces of Ireland. The order of the provinces varies.

Various all-Ireland sports teams and organisations use the Four Provinces Flag of Ireland and a four province Crest of Ireland, including the Ireland field hockey team, Ireland rugby league team, Irish rugby union team and Irish Amateur Boxing Association.

Erne flag

[edit]This flag was initially used on the Shannon–Erne Waterway, which is bisected by the border. Rather than flying a national flag, boats fly this green, white and blue flag.[6][failed verification] It is endorsed by the Inland Waterways Association of Ireland, an all-island organisation.[7] This design is, however, very similar to the national flag of Sierra Leone.

Harp flags

[edit]The harp (or cláirseach) has long been a symbol of Ireland, being first recorded in a French roll of arms known as the Armorial Wijnbergen, which dates to the late 13th century. It first featured on Irish coins in the reign of Henry VIII around 1534.[8] During the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the harp became adorned with progressively more decoration, ultimately becoming a "winged maiden".[9][10] In the nineteenth century, the Maid of Erin, a personification of Ireland, was a woman holding a more realistic harp than the "winged maiden". This style of harp was then also used in Irish flags. The harp on the modern coat of arms of Ireland is modelled on the "Brian Boru" harp in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, as it appeared after an 1840s restoration.

Blue harp flag

[edit]The lower left quadrant of the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom has featured a harp on a blue field, representing Ireland since 1603.[8] The current version, designed in 1953, uses a winged-maiden harp and consists of a golden cláirseach with silver strings on a blue background. The shade of blue in the field was known as Saint Patrick's Blue when used in 1783 for the regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick.[11]

-

Standard of the president of Ireland

-

Quarter of the Royal Standard

Green harp flag

[edit]The flag of a harp on a green background was first used by Owen Roe O'Neil in 1642. The change from blue to green started in the 17th century with Owen Roe O'Neill and Confederate Ireland,[12] The colour green became associated with Ireland from the 1640s onwards. The United Irishmen adopted this flag which already had strong associations with Ireland, it was unofficially the national flag for centuries, The united Irishmen was an Irish nationalist movement associated with both Catholic and Protestant Irish – its leader Wolfe Tone was Anglican Protestant; green was a colour of rebellion in the eighteenth century.[13] Since at least the 17th century Ireland has been known by the poetic name the Emerald Isle due to its abundance of green countryside.[14] This was a common flag used to represent Ireland during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It consisted of a gold cláirseach on a green background. It was associated with moderate nationalism at a time when the tricolour was confined to more radical movements.[citation needed] It is the same as the modern Flag of Leinster. It was used by the Irish team at the 1930 British Empire Games.

Sporting flags

[edit]Several all-island sporting organisations send representative teams to compete internationally. In some cases, a flag unique to that organisation is used in lieu of a national flag. Typically such flags include one of the traditional symbols of Ireland.

Cricket Ireland uses a green flag depicting three shamrocks.

The Ireland national field hockey team uses a bespoke flag with a shield quartered with the symbols of the four provinces.

The Ireland rugby team's flag is a green flag containing the shields of the four provinces and the Irish Rugby Football Union's logo. At matches outside Ireland, this is the only flag displayed. At matches in Northern Ireland (typically at Ravenhill) the Flag of Ulster (yellow background) is also displayed. This is the flag of the nine-county province (including the three Ulster counties in the Republic of Ireland), similar to but distinct from the Ulster Banner (white background), the former flag of the Northern Irish government. At matches in the Republic of Ireland (typically at Lansdowne Road), the Irish tricolour is flown along with the preceding two.

Eddie Irvine, a Formula One driver from Conlig in Northern Ireland, asked for a white flag with a shamrock to be used if he secured a podium finish.[15] There had been controversy when an Irish tricolour had been used incorrectly for him in 1997.[15] The FIA insisted the Union Flag be used in conformance with its regulations.[15]

The Show Jumping Association of Ireland (SJAI; subsequently renamed Showjumping Ireland) used a green flag with its crest based on the four provinces when competing internationally, from its formation after the Second World War. In FEI Nations Cup events, Ireland was represented by the Irish Army Equitation School under the tricolour. From the late 1960s, the SJAI joined forces with the army in FEI competitions and competed under the tricolour, although it retained its own flag in other competitions until the late 1970s.[16]

-

Ireland rugby team flag

-

Ireland cricket team flag

-

Ireland hockey team flag

-

Ireland quidditch team flag

See also

[edit]- Northern Ireland flags issue

- "Ireland's Call", used as a national anthem for the rugby union team

- Korean Unification Flag, used by Unified Korean sporting teams when North Korea and South Korea participate as one team

References

[edit]- ^ Church of Ireland (April 1999). "Church of Ireland General Synod Sub Committee on Sectarianism Report".: Resolution One: The General Synod of the Church of Ireland recognises that from time to time confusion and controversy have attended the flying of flags on church buildings or within the grounds of church buildings. This Synod therefore resolves that the only flags specifically authorised to be flown on church buildings or within the church grounds of the Church of Ireland are the cross of St Patrick or, alternatively, the flag of the Anglican Communion bearing the emblem of the Compassrose. Such flags are authorised to be flown only on Holy Days and during the Octaves of Christmas, Easter, the Ascension of Our Lord and Pentecost, and on any other such day as may be recognised locally as the Dedication Day of the particular church building. Any other flag flown at any other time is not specifically authorised by this Church.

- ^ Dillon, Jim (1995). "The Evolution of Maritime Uniform". Beam. 24. Commissioners of Irish Lights. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

In the Lighthouse Service the cap badge originally was a St George's Cross surrounded by a wreath of laurel leaves but from 1970 the St Patrick's Cross has been used.

- ^ McNally, Frank (25 August 2023). "Bloody Oath – Frank McNally on the red-handed tricolour". IrishTimes.com.

- ^ http://stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk/stormontpapers/pageview.html?volumeno=35&pageno=2093&searchTerm=tricolour#bak-35-2073. Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 35. Commons N.I. 21 August 1951. col. 2073.

{{cite book}}:|chapter-url=missing title (help) Archived 16 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine - ^ MacGinty, Karl (4 November 2008). "McDowell and McGinley fly the flag for Ireland". Irish Independent. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ "Lough Erne Flag & IWAI Pennants". Lough Erne Flag. IWAI. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ "Erne Flag". Inland Waterways Association of Ireland. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ a b Morris, Ewan (2005). Our own devices: National symbols and polititcal conflict in Twentieth-Century Ireland. Irish Academic Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-7165-2663-8.

- ^ Burgers, Andries (21 May 2006). "Ireland: Green Flag". Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Boydell, Barra (1996). "The Iconography of the Irish Harp as a National Symbol". In Patrick F. Devine & Harry White (ed.). Irish Musical Studies. Vol. 5. Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-261-5.

- ^ Cullen, Fintan (1995). "Visual Politics in 1780s Ireland: The Roles of History Painting". Oxford Art Journal. 18 (1). Oxford University Press: 65. doi:10.1093/oxartj/18.1.58. JSTOR 1360595.

- ^ Andries Burgers (21 May 2006). "Ireland: Green Flag". Flags of the World. Citing G. A. Hayes-McCoy, A History of Irish Flags from earliest times (1979)

- ^ Naval Service – Flags and Pennants Archived 23 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How did Ireland come to be called the Emerald Isle?". 13 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "Sporting political gestures". The Irish Times. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ Slavin, Michael (1998). Showjumping Legends: Ireland, 1868–1998. Wolfhound Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780863276576.