Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Join (SQL)

View on Wikipedia

A join clause in the Structured Query Language (SQL) combines columns from one or more tables into a new table. The operation corresponds to a join operation in relational algebra. Informally, a join stitches two tables and puts on the same row records with matching fields. There are several variants of JOIN: INNER, LEFT OUTER, RIGHT OUTER, FULL OUTER, CROSS, and others.

Example tables

[edit]To explain join types, the rest of this article uses the following tables:

| LastName | DepartmentID |

|---|---|

| Rafferty | 31 |

| Jones | 33 |

| Heisenberg | 33 |

| Robinson | 34 |

| Smith | 34 |

| Williams | NULL

|

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|

| 31 | Sales |

| 33 | Engineering |

| 34 | Clerical |

| 35 | Marketing |

Department.DepartmentID is the primary key of the Department table, whereas Employee.DepartmentID is a foreign key.

Note that in Employee, "Williams" has not yet been assigned to a department. Also, no employees have been assigned to the "Marketing" department.

These are the SQL statements to create the above tables:

CREATE TABLE department(

DepartmentID INT PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL,

DepartmentName VARCHAR(20)

);

CREATE TABLE employee (

LastName VARCHAR(20),

DepartmentID INT REFERENCES department(DepartmentID)

);

INSERT INTO department

VALUES (31, 'Sales'),

(33, 'Engineering'),

(34, 'Clerical'),

(35, 'Marketing');

INSERT INTO employee

VALUES ('Rafferty', 31),

('Jones', 33),

('Heisenberg', 33),

('Robinson', 34),

('Smith', 34),

('Williams', NULL);

Cross join

[edit]CROSS JOIN returns the Cartesian product of rows from tables in the join. In other words, it will produce rows which combine each row from the first table with each row from the second table.[1]

| Employee.LastName | Employee.DepartmentID | Department.DepartmentName | Department.DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rafferty | 31 | Sales | 31 |

| Jones | 33 | Sales | 31 |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Sales | 31 |

| Smith | 34 | Sales | 31 |

| Robinson | 34 | Sales | 31 |

| Williams | NULL |

Sales | 31 |

| Rafferty | 31 | Engineering | 33 |

| Jones | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Smith | 34 | Engineering | 33 |

| Robinson | 34 | Engineering | 33 |

| Williams | NULL |

Engineering | 33 |

| Rafferty | 31 | Clerical | 34 |

| Jones | 33 | Clerical | 34 |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Clerical | 34 |

| Smith | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Robinson | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Williams | NULL |

Clerical | 34 |

| Rafferty | 31 | Marketing | 35 |

| Jones | 33 | Marketing | 35 |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Marketing | 35 |

| Smith | 34 | Marketing | 35 |

| Robinson | 34 | Marketing | 35 |

| Williams | NULL |

Marketing | 35 |

Example of an explicit cross join:

SELECT *

FROM employee CROSS JOIN department;

Example of an implicit cross join:

SELECT *

FROM employee, department;

The cross join can be replaced with an inner join with an always-true condition:

SELECT *

FROM employee INNER JOIN department ON 1=1;

CROSS JOIN does not itself apply any predicate to filter rows from the joined table. The results of a CROSS JOIN can be filtered using a WHERE clause, which may then produce the equivalent of an inner join.

In the SQL:2011 standard, cross joins are part of the optional F401, "Extended joined table", package.

Normal uses are for checking the server's performance.[why?]

Inner join

[edit]An inner join (or join) requires each row in the two joined tables to have matching column values, and is a commonly used join operation in applications but should not be assumed to be the best choice in all situations. Inner join creates a new result table by combining column values of two tables (A and B) based upon the join-predicate. The query compares each row of A with each row of B to find all pairs of rows that satisfy the join-predicate. When the join-predicate is satisfied by matching non-NULL values, column values for each matched pair of rows of A and B are combined into a result row.

The result of the join can be defined as the outcome of first taking the cartesian product (or cross join) of all rows in the tables (combining every row in table A with every row in table B) and then returning all rows that satisfy the join predicate. Actual SQL implementations normally use other approaches, such as hash joins or sort-merge joins, since computing the Cartesian product is slower and would often require a prohibitively large amount of memory to store.

SQL specifies two different syntactical ways to express joins: the "explicit join notation" and the "implicit join notation". The "implicit join notation" is no longer considered a best practice[by whom?], although database systems still support it.

The "explicit join notation" uses the JOIN keyword, optionally preceded by the INNER keyword, to specify the table to join, and the ON keyword to specify the predicates for the join, as in the following example:

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID, department.DepartmentName

FROM employee

INNER JOIN department ON

employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

| Employee.LastName | Employee.DepartmentID | Department.DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|

| Robinson | 34 | Clerical |

| Jones | 33 | Engineering |

| Smith | 34 | Clerical |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Engineering |

| Rafferty | 31 | Sales |

The "implicit join notation" simply lists the tables for joining, in the FROM clause of the SELECT statement, using commas to separate them. Thus it specifies a cross join, and the WHERE clause may apply additional filter-predicates (which function comparably to the join-predicates in the explicit notation).

The following example is equivalent to the previous one, but this time using implicit join notation:

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID, department.DepartmentName

FROM employee, department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

The queries given in the examples above will join the Employee and department tables using the DepartmentID column of both tables. Where the DepartmentID of these tables match (i.e. the join-predicate is satisfied), the query will combine the LastName, DepartmentID and DepartmentName columns from the two tables into a result row. Where the DepartmentID does not match, no result row is generated.

Thus the result of the execution of the query above will be:

| Employee.LastName | Employee.DepartmentID | Department.DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|

| Robinson | 34 | Clerical |

| Jones | 33 | Engineering |

| Smith | 34 | Clerical |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Engineering |

| Rafferty | 31 | Sales |

The employee "Williams" and the department "Marketing" do not appear in the query execution results. Neither of these has any matching rows in the other respective table: "Williams" has no associated department, and no employee has the department ID 35 ("Marketing"). Depending on the desired results, this behavior may be a subtle bug, which can be avoided by replacing the inner join with an outer join.

Inner join and NULL values

[edit]Programmers should take special care when joining tables on columns that can contain NULL values, since NULL will never match any other value (not even NULL itself), unless the join condition explicitly uses a combination predicate that first checks that the joins columns are NOT NULL before applying the remaining predicate condition(s). The Inner Join can only be safely used in a database that enforces referential integrity or where the join columns are guaranteed not to be NULL. Many transaction processing relational databases rely on atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability (ACID) data update standards to ensure data integrity, making inner joins an appropriate choice. However, transaction databases usually also have desirable join columns that are allowed to be NULL. Many reporting relational database and data warehouses use high volume extract, transform, load (ETL) batch updates which make referential integrity difficult or impossible to enforce, resulting in potentially NULL join columns that an SQL query author cannot modify and which cause inner joins to omit data with no indication of an error. The choice to use an inner join depends on the database design and data characteristics. A left outer join can usually be substituted for an inner join when the join columns in one table may contain NULL values.

Any data column that may be NULL (empty) should never be used as a link in an inner join, unless the intended result is to eliminate the rows with the NULL value. If NULL join columns are to be deliberately removed from the result set, an inner join can be faster than an outer join because the table join and filtering is done in a single step. Conversely, an inner join can result in disastrously slow performance or even a server crash when used in a large volume query in combination with database functions in an SQL Where clause. [2] [3] [4], A function in an SQL Where clause can result in the database ignoring relatively compact table indexes. The database may read and inner join the selected columns from both tables before reducing the number of rows using the filter that depends on a calculated value, resulting in a relatively enormous amount of inefficient processing.

When a result set is produced by joining several tables, including master tables used to look up full-text descriptions of numeric identifier codes (a Lookup table), a NULL value in any one of the foreign keys can result in the entire row being eliminated from the result set, with no indication of error. A complex SQL query that includes one or more inner joins and several outer joins has the same risk for NULL values in the inner join link columns.

A commitment to SQL code containing inner joins assumes NULL join columns will not be introduced by future changes, including vendor updates, design changes and bulk processing outside of the application's data validation rules such as data conversions, migrations, bulk imports and merges.

One can further classify inner joins as equi-joins, as natural joins, or as cross-joins.

Equi-join

[edit]The equi-join, also known as "the only eligible operation", is a specific type of comparator-based join, that uses only equality comparisons in the join-predicate. Using other comparison operators (such as <) disqualifies a join as an equi-join. The query shown above has already provided an example of an equi-join:

SELECT *

FROM employee JOIN department

ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

We can write equi-join as below,

SELECT *

FROM employee, department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

If columns in an equi-join have the same name, SQL-92 provides an optional shorthand notation for expressing equi-joins, by way of the USING construct:[5]

SELECT *

FROM employee INNER JOIN department USING (DepartmentID);

The USING construct is more than mere syntactic sugar, however, since the result set differs from the result set of the version with the explicit predicate. Specifically, any columns mentioned in the USING list will appear only once, with an unqualified name, rather than once for each table in the join. In the case above, there will be a single DepartmentID column and no employee.DepartmentID or department.DepartmentID.

The USING clause is not supported by MS SQL Server and Sybase.

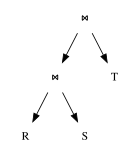

Natural join

[edit]The natural join is a special case of equi-join. Natural join (⋈) is a binary operator that is written as (R ⋈ S) where R and S are relations.[6] The result of the natural join is the set of all combinations of tuples in R and S that are equal on their common attribute names. For an example consider the tables Employee and Dept and their natural join:

|

|

|

This can also be used to define composition of relations. For example, the composition of Employee and Dept is their join as shown above, projected on all but the common attribute DeptName. In category theory, the join is precisely the fiber product.

The natural join is arguably one of the most important operators since it is the relational counterpart of logical AND. Note that if the same variable appears in each of two predicates that are connected by AND, then that variable stands for the same thing and both appearances must always be substituted by the same value. In particular, the natural join allows the combination of relations that are associated by a foreign key. For example, in the above example a foreign key probably holds from Employee.DeptName to Dept.DeptName and then the natural join of Employee and Dept combines all employees with their departments. This works because the foreign key holds between attributes with the same name. If this is not the case such as in the foreign key from Dept.manager to Employee.Name then these columns have to be renamed before the natural join is taken. Such a join is sometimes also referred to as an equi-join.

More formally the semantics of the natural join are defined as follows:

- ,

where Fun is a predicate that is true for a relation r if and only if r is a function. It is usually required that R and S must have at least one common attribute, but if this constraint is omitted, and R and S have no common attributes, then the natural join becomes exactly the Cartesian product.

The natural join can be simulated with Codd's primitives as follows. Let c1, ..., cm be the attribute names common to R and S, r1, ..., rn be the attribute names unique to R and let s1, ..., sk be the attributes unique to S. Furthermore, assume that the attribute names x1, ..., xm are neither in R nor in S. In a first step the common attribute names in S can now be renamed:

Then we take the Cartesian product and select the tuples that are to be joined:

A natural join is a type of equi-join where the join predicate arises implicitly by comparing all columns in both tables that have the same column-names in the joined tables. The resulting joined table contains only one column for each pair of equally named columns. In the case that no columns with the same names are found, the result is a cross join.

Most experts agree that NATURAL JOINs are dangerous and therefore strongly discourage their use.[7] The danger comes from inadvertently adding a new column, named the same as another column in the other table. An existing natural join might then "naturally" use the new column for comparisons, making comparisons/matches using different criteria (from different columns) than before. Thus an existing query could produce different results, even though the data in the tables have not been changed, but only augmented. The use of column names to automatically determine table links is not an option in large databases with hundreds or thousands of tables where it would place an unrealistic constraint on naming conventions. Real world databases are commonly designed with foreign key data that is not consistently populated (NULL values are allowed), due to business rules and context. It is common practice to modify column names of similar data in different tables and this lack of rigid consistency relegates natural joins to a theoretical concept for discussion.

The above sample query for inner joins can be expressed as a natural join in the following way:

SELECT *

FROM employee NATURAL JOIN department;

As with the explicit USING clause, only one DepartmentID column occurs in the joined table, with no qualifier:

| DepartmentID | Employee.LastName | Department.DepartmentName |

|---|---|---|

| 34 | Smith | Clerical |

| 33 | Jones | Engineering |

| 34 | Robinson | Clerical |

| 33 | Heisenberg | Engineering |

| 31 | Rafferty | Sales |

PostgreSQL, MySQL and Oracle support natural joins; Microsoft T-SQL and IBM DB2 do not. The columns used in the join are implicit so the join code does not show which columns are expected, and a change in column names may change the results. In the SQL:2011 standard, natural joins are part of the optional F401, "Extended joined table", package.

In many database environments the column names are controlled by an outside vendor, not the query developer. A natural join assumes stability and consistency in column names which can change during vendor mandated version upgrades.

Outer join

[edit]The joined table retains each row—even if no other matching row exists. Outer joins subdivide further into left outer joins, right outer joins, and full outer joins, depending on which table's rows are retained: left, right, or both (in this case left and right refer to the two sides of the JOIN keyword). Like inner joins, one can further sub-categorize all types of outer joins as equi-joins, natural joins, ON <predicate> (θ-join), etc.[8]

No implicit join-notation for outer joins exists in standard SQL.

Left outer join

[edit]The result of a left outer join (or simply left join) for tables A and B always contains all rows of the "left" table (A), even if the join-condition does not find any matching row in the "right" table (B). This means that if the ON clause matches 0 (zero) rows in B (for a given row in A), the join will still return a row in the result (for that row)—but with NULL in each column from B. A left outer join returns all the values from an inner join plus all values in the left table that do not match to the right table, including rows with NULL (empty) values in the link column.

For example, this allows us to find an employee's department, but still shows employees that have not been assigned to a department (contrary to the inner-join example above, where unassigned employees were excluded from the result).

Example of a left outer join (the OUTER keyword is optional), with the additional result row (compared with the inner join) italicized:

SELECT *

FROM employee

LEFT OUTER JOIN department ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

| Employee.LastName | Employee.DepartmentID | Department.DepartmentName | Department.DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jones | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Rafferty | 31 | Sales | 31 |

| Robinson | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Smith | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Williams | NULL |

NULL |

NULL

|

| Heisenberg | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

Alternative syntaxes

[edit]Oracle supports the deprecated[9] syntax:

SELECT *

FROM employee, department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID(+)

Sybase supports the syntax (Microsoft SQL Server deprecated this syntax since version 2000):

SELECT *

FROM employee, department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID *= department.DepartmentID

IBM Informix supports the syntax:

SELECT *

FROM employee, OUTER department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID

Right outer join

[edit]A right outer join (or right join) closely resembles a left outer join, except with the treatment of the tables reversed. Every row from the "right" table (B) will appear in the joined table at least once. If no matching row from the "left" table (A) exists, NULL will appear in columns from A for those rows that have no match in B.

A right outer join returns all the values from the right table and matched values from the left table (NULL in the case of no matching join predicate). For example, this allows us to find each employee and his or her department, but still show departments that have no employees.

Below is an example of a right outer join (the OUTER keyword is optional), with the additional result row italicized:

SELECT *

FROM employee RIGHT OUTER JOIN department

ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

| Employee.LastName | Employee.DepartmentID | Department.DepartmentName | Department.DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Jones | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Robinson | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Heisenberg | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Rafferty | 31 | Sales | 31 |

NULL |

NULL |

Marketing | 35 |

Right and left outer joins are functionally equivalent. Neither provides any functionality that the other does not, so right and left outer joins may replace each other as long as the table order is switched.

Full outer join

[edit]Conceptually, a full outer join combines the effect of applying both left and right outer joins. Where rows in the full outer joined tables do not match, the result set will have NULL values for every column of the table that lacks a matching row. For those rows that do match, a single row will be produced in the result set (containing columns populated from both tables).

For example, this allows us to see each employee who is in a department and each department that has an employee, but also see each employee who is not part of a department and each department which doesn't have an employee.

Example of a full outer join (the OUTER keyword is optional):

SELECT *

FROM employee FULL OUTER JOIN department

ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

| Employee.LastName | Employee.DepartmentID | Department.DepartmentName | Department.DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Jones | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Robinson | 34 | Clerical | 34 |

| Williams | NULL |

NULL |

NULL

|

| Heisenberg | 33 | Engineering | 33 |

| Rafferty | 31 | Sales | 31 |

NULL |

NULL |

Marketing | 35 |

Some database systems do not support the full outer join functionality directly, but they can emulate it through the use of an inner join and UNION ALL selects of the "single table rows" from left and right tables respectively. The same example can appear as follows:

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID,

department.DepartmentName, department.DepartmentID

FROM employee

INNER JOIN department ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID

UNION ALL

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID,

cast(NULL as varchar(20)), cast(NULL as integer)

FROM employee

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT * FROM department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID)

UNION ALL

SELECT cast(NULL as varchar(20)), cast(NULL as integer),

department.DepartmentName, department.DepartmentID

FROM department

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT * FROM employee

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID)

Another approach could be UNION ALL of left outer join and right outer join MINUS inner join.

Self-join

[edit]A self-join is joining a table to itself.[10]

Example

[edit]If there were two separate tables for employees and a query which requested employees in the first table having the same country as employees in the second table, a normal join operation could be used to find the answer table. However, all the employee information is contained within a single large table.[11]

Consider a modified Employee table such as the following:

| EmployeeID | LastName | Country | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 123 | Rafferty | Australia | 31 |

| 124 | Jones | Australia | 33 |

| 145 | Heisenberg | Australia | 33 |

| 201 | Robinson | United States | 34 |

| 305 | Smith | Germany | 34 |

| 306 | Williams | Germany | NULL

|

An example solution query could be as follows:

SELECT F.EmployeeID, F.LastName, S.EmployeeID, S.LastName, F.Country

FROM Employee F INNER JOIN Employee S ON F.Country = S.Country

WHERE F.EmployeeID < S.EmployeeID

ORDER BY F.EmployeeID, S.EmployeeID;

Which results in the following table being generated.

| EmployeeID | LastName | EmployeeID | LastName | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 123 | Rafferty | 124 | Jones | Australia |

| 123 | Rafferty | 145 | Heisenberg | Australia |

| 124 | Jones | 145 | Heisenberg | Australia |

| 305 | Smith | 306 | Williams | Germany |

For this example:

FandSare aliases for the first and second copies of the employee table.- The condition

F.Country = S.Countryexcludes pairings between employees in different countries. The example question only wanted pairs of employees in the same country. - The condition

F.EmployeeID < S.EmployeeIDexcludes pairings where theEmployeeIDof the first employee is greater than or equal to theEmployeeIDof the second employee. In other words, the effect of this condition is to exclude duplicate pairings and self-pairings. Without it, the following less useful table would be generated (the table below displays only the "Germany" portion of the result):

| EmployeeID | LastName | EmployeeID | LastName | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 305 | Smith | 305 | Smith | Germany |

| 305 | Smith | 306 | Williams | Germany |

| 306 | Williams | 305 | Smith | Germany |

| 306 | Williams | 306 | Williams | Germany |

Only one of the two middle pairings is needed to satisfy the original question, and the topmost and bottommost are of no interest at all in this example.

Alternatives

[edit]The effect of an outer join can also be obtained using a UNION ALL between an INNER JOIN and a SELECT of the rows in the "main" table that do not fulfill the join condition. For example,

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID, department.DepartmentName

FROM employee

LEFT OUTER JOIN department ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID;

can also be written as

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID, department.DepartmentName

FROM employee

INNER JOIN department ON employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID

UNION ALL

SELECT employee.LastName, employee.DepartmentID, cast(NULL as varchar(20))

FROM employee

WHERE NOT EXISTS (

SELECT * FROM department

WHERE employee.DepartmentID = department.DepartmentID)

Implementation

[edit]Much work in database-systems has aimed at efficient implementation of joins, because relational systems commonly call for joins, yet face difficulties in optimising their efficient execution. The problem arises because inner joins operate both commutatively and associatively. In practice, this means that the user merely supplies the list of tables for joining and the join conditions to use, and the database system has the task of determining the most efficient way to perform the operation. The choices become more complex as the number of tables involved in a query increases, with each table having different characteristics in record count, average record length (considering NULL fields) and available indexes. Where Clause filters can also significantly impact query volume and cost.

A query optimizer determines how to execute a query containing joins. A query optimizer has two basic freedoms:

- Join order: Because it joins functions commutatively and associatively, the order in which the system joins tables does not change the final result set of the query. However, join-order could have an enormous impact on the cost of the join operation, so choosing the best join order becomes very important.

- Join method: Given two tables and a join condition, multiple algorithms can produce the result set of the join. Which algorithm runs most efficiently depends on the sizes of the input tables, the number of rows from each table that match the join condition, and the operations required by the rest of the query.

Many join-algorithms treat their inputs differently. One can refer to the inputs to a join as the "outer" and "inner" join operands, or "left" and "right", respectively. In the case of nested loops, for example, the database system will scan the entire inner relation for each row of the outer relation.

One can classify query-plans involving joins as follows:[12]

- left-deep

- using a base table (rather than another join) as the inner operand of each join in the plan

- right-deep

- using a base table as the outer operand of each join in the plan

- bushy

- neither left-deep nor right-deep; both inputs to a join may themselves result from joins

These names derive from the appearance of the query plan if drawn as a tree, with the outer join relation on the left and the inner relation on the right (as convention dictates).

Join algorithms

[edit]

Three fundamental algorithms for performing a binary join operation exist: nested loop join, sort-merge join and hash join. Worst-case optimal join algorithms are asymptotically faster than binary join algorithms for joins between more than two relations in the worst case.

Join indexes

[edit]Join indexes are database indexes that facilitate the processing of join queries in data warehouses: they are currently (2012) available in implementations by Oracle[14] and Teradata.[15]

In the Teradata implementation, specified columns, aggregate functions on columns, or components of date columns from one or more tables are specified using a syntax similar to the definition of a database view: up to 64 columns/column expressions can be specified in a single join index. Optionally, a column that defines the primary key of the composite data may also be specified: on parallel hardware, the column values are used to partition the index's contents across multiple disks. When the source tables are updated interactively by users, the contents of the join index are automatically updated. Any query whose WHERE clause specifies any combination of columns or column expressions that are an exact subset of those defined in a join index (a so-called "covering query") will cause the join index, rather than the original tables and their indexes, to be consulted during query execution.

The Oracle implementation limits itself to using bitmap indexes. A bitmap join index is used for low-cardinality columns (i.e., columns containing fewer than 300 distinct values, according to the Oracle documentation): it combines low-cardinality columns from multiple related tables. The example Oracle uses is that of an inventory system, where different suppliers provide different parts. The schema has three linked tables: two "master tables", Part and Supplier, and a "detail table", Inventory. The last is a many-to-many table linking Supplier to Part, and contains the most rows. Every part has a Part Type, and every supplier is based in the US, and has a State column. There are not more than 60 states+territories in the US, and not more than 300 Part Types. The bitmap join index is defined using a standard three-table join on the three tables above, and specifying the Part_Type and Supplier_State columns for the index. However, it is defined on the Inventory table, even though the columns Part_Type and Supplier_State are "borrowed" from Supplier and Part respectively.

As for Teradata, an Oracle bitmap join index is only utilized to answer a query when the query's WHERE clause specifies columns limited to those that are included in the join index.

Straight join

[edit]Some database systems allow the user to force the system to read the tables in a join in a particular order. This is used when the join optimizer chooses to read the tables in an inefficient order. For example, in MySQL the command STRAIGHT_JOIN reads the tables in exactly the order listed in the query.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ SQL CROSS JOIN

- ^ Robidoux, Greg (2007-05-03). "Avoid SQL Server functions in the WHERE clause for Performance". MSSQL Tips.

- ^ Wolf, Patrick (2006-11-30). "Inside Oracle APEX "Caution when using PL/SQL functions in a SQL statement". Inside Oracle APEX. Archived from the original on 2018-12-27.

- ^ Larsen, Gregory A. (2009-10-29). "T-SQL Best Practices - Don't Use Scalar Value Functions in Column List or WHERE Clauses". Database Journal.

- ^ Simplifying Joins with the USING Keyword

- ^ In Unicode, the bowtie symbol is ⋈ (U+22C8).

- ^ Ask Tom "Oracle support of ANSI joins." Back to basics: inner joins » Eddie Awad's Blog Archived 2010-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Silberschatz, Abraham; Korth, Hank; Sudarshan, S. (2002). "Section 4.10.2: Join Types and Conditions". Database System Concepts (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 166. ISBN 0072283637.

- ^ Oracle Left Outer Join

- ^ Shah 2005, p. 165

- ^ Adapted from Pratt 2005, pp. 115–6

- ^ Yu & Meng 1998, p. 213

- ^ Wang, Yisu Remy; Willsey, Max; Suciu, Dan (2023-01-27). "Free Join: Unifying Worst-Case Optimal and Traditional Joins". arXiv:2301.10841 [cs.DB].

- ^ Oracle Bitmap Join Indexes. "Database Concepts - 5 Indexes and Index-Organized Tables - Bitmap Join Indexes". Retrieved 2024-06-23.

- ^ Teradata Join Indexes. "SQL Data Definition Language Syntax and Examples - CREATE JOIN INDEX". Retrieved 2024-06-23.

- ^ "13.2.9.2 JOIN Syntax". MySQL 5.7 Reference Manual. Oracle Corporation. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

Sources

[edit]- Pratt, Phillip J (2005), A Guide To SQL, Seventh Edition, Thomson Course Technology, ISBN 978-0-619-21674-0

- Shah, Nilesh (2005) [2002], Database Systems Using Oracle – A Simplified Guide to SQL and PL/SQL Second Edition (International ed.), Pearson Education International, ISBN 0-13-191180-5

- Yu, Clement T.; Meng, Weiyi (1998), Principles of Database Query Processing for Advanced Applications, Morgan Kaufmann, ISBN 978-1-55860-434-6, retrieved 2009-03-03

External links

[edit]Join (SQL)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

In SQL, a join is a fundamental operation that combines rows from two or more tables into a single result set based on a specified matching condition, typically involving related columns.[5] This mechanism allows queries to retrieve and relate data across normalized tables, treating them as interconnected entities within a relational database management system (RDBMS).[7] The primary purpose of joins is to enable efficient querying in normalized database designs, where data redundancy is minimized by dividing information into separate tables linked through keys rather than repeating values across structures.[8] By specifying how tables relate—often via primary and foreign keys—joins support complex data retrieval without compromising the integrity or storage efficiency of the underlying relational model.[5] The join concept was introduced by E. F. Codd in his 1970 paper "A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks," which proposed relational algebra operations, including the join, to manipulate data relations mathematically and independently of physical storage.[8] Joins were later incorporated into SQL, with the language standardized by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) as SQL-86 in 1986 and by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) as ISO 9075 in 1987; subsequent revisions, such as SQL-92, further refined their implementation.[9][10] A basic join syntax in SQL follows the formSELECT column_list FROM table1 JOIN table2 ON join_condition;, where the ON clause defines the matching criteria between tables.[5] Effective use of joins presupposes knowledge of relational tables—structured as rows and columns—along with primary keys, which uniquely identify rows in a table, and foreign keys, which reference those primary keys to enforce relationships and data integrity across tables.[11]

Sample Database Tables

To illustrate SQL join operations throughout this article, two sample relational tables are used: the "Employees" table and the "Departments" table. These tables represent a basic organizational database where employees are associated with departments, allowing demonstration of how joins combine data across related entities to retrieve meaningful information. The "Employees" table contains information about individual employees, with the following structure:| EmployeeID | Name | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 101 |

| 2 | Bob | 102 |

| 3 | Charlie | 101 |

| 4 | Dana | NULL |

| 5 | Eve | 103 |

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|

| 101 | HR |

| 102 | Engineering |

| 103 | Sales |

Cartesian and Inner Joins

Cross Join

A cross join in SQL, also known as a Cartesian join, produces the Cartesian product of two tables by pairing every row from the first table with every row from the second table, without any matching condition. This results in a result set containing m × n rows, where m is the number of rows in the first table and n is the number of rows in the second table.[5][12] The explicit syntax for a cross join follows the ANSI SQL standard:SELECT column_list FROM table1 CROSS JOIN table2. An implicit form uses a comma to separate the tables in the FROM clause: SELECT column_list FROM table1, table2, which achieves the same Cartesian product effect.[13][14]

Cross joins are primarily used to generate all possible combinations of rows from two tables, such as creating synthetic test data or preparing datasets for combinatorial analysis like permutations. They are rarely employed in production environments because the output can grow exponentially large, making them impractical for sizable tables.[14][15][13]

For illustration, consider sample tables: an Employees table with 5 rows (columns: EmployeeID, Name) and a Departments table with 3 rows (columns: DeptID, DeptName). The query SELECT * FROM Employees CROSS JOIN Departments yields 15 rows total.

| EmployeeID | Name | DeptID | DeptName |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John | 1 | HR |

| 1 | John | 2 | IT |

| 1 | John | 3 | Finance |

| 2 | Jane | 1 | HR |

| 2 | Jane | 2 | IT |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

Inner Join

The inner join is a fundamental operation in SQL that combines rows from two or more tables based on a matching condition, returning only those rows where the condition is satisfied in both tables. It represents a subset of the Cartesian product (cross join) where the results are filtered to include solely the pairs of rows that meet the specified join predicate, typically an equality comparison between columns such as primary and foreign keys.[16][5] The standard SQL syntax for an inner join uses theINNER JOIN keyword followed by the second table and an ON clause specifying the join condition:

SELECT column_list

FROM table1

INNER JOIN table2 ON table1.column = table2.column;

SELECT column_list

FROM table1

INNER JOIN table2 ON table1.column = table2.column;

table1.key = table2.key), though other predicates like inequalities can be used in some implementations. Key properties include that only rows with matches are returned—if no matches exist for a row in one table, it is excluded entirely; the operation is commutative, meaning swapping the order of the tables yields the same result set; and it preserves the distinctness of rows unless duplicates arise from the data itself.[16][5]

To illustrate, consider two sample tables: Employees (with columns EmployeeID, Name, DepartmentID) containing five rows, including one with a NULL DepartmentID; and Departments (with columns DepartmentID, DepartmentName) containing four rows. The query:

SELECT e.Name, d.DepartmentName

FROM Employees e

INNER JOIN Departments d ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID;

SELECT e.Name, d.DepartmentName

FROM Employees e

INNER JOIN Departments d ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID;

DepartmentID and any unmatched departments:

| Name | DepartmentName |

|---|---|

| Alice | Human Resources |

| Bob | Information Technology |

| Charlie | Sales |

| Dana | Finance |

Equi-Join and Natural Join

An equi-join is a specialized form of inner join in which the join condition exclusively uses the equality operator (=) to match rows from two or more tables based on identical values in specified columns. This approach ensures precise row combinations where the compared columns hold equivalent data, making it the predominant method for linking tables in relational databases.[3] Equi-joins underpin foreign key relationships by aligning primary keys from one table with foreign keys in another, facilitating accurate data associations without extraneous matches.[18] For instance, consider two sample tables: aCustomers table with columns customer_id and name, and an Orders table with columns order_id, customer_id, and amount. An equi-join query might appear as:

SELECT Customers.name, Orders.order_id, Orders.amount

FROM Customers

INNER JOIN Orders ON Customers.customer_id = Orders.customer_id;

SELECT Customers.name, Orders.order_id, Orders.amount

FROM Customers

INNER JOIN Orders ON Customers.customer_id = Orders.customer_id;

customer_id values match exactly, producing a result set that combines customer names with their corresponding orders.

A natural join extends the equi-join concept by automatically performing the equality matching on all columns that share identical names and compatible data types between the tables, eliminating the need for an explicit ON clause.[19] The syntax simplifies to FROM table1 NATURAL JOIN table2, where the database engine identifies common columns—such as customer_id in the previous example—and joins solely on those using equality. Using the same Customers and Orders tables, the natural join would yield identical results to the explicit equi-join if customer_id is the only matching column:

SELECT Customers.name, Orders.order_id, Orders.amount

FROM Customers

NATURAL JOIN Orders;

SELECT Customers.name, Orders.order_id, Orders.amount

FROM Customers

NATURAL JOIN Orders;

region exist with the same name in both tables but represent unrelated data, the natural join would unexpectedly match on both customer_id and region, potentially producing incorrect or bloated results.[20]

Natural joins carry risks of unintended matches when column names overlap coincidentally across tables, leading to ambiguous or erroneous query outcomes that are difficult to debug.[20] This implicit behavior also reduces portability across database schemas, as renaming columns or adding new ones with common names can alter join logic without warning.[19] Consequently, natural joins are often discouraged in favor of explicit equi-joins for maintainability, though they remain useful in controlled scenarios with well-designed schemas.

Both equi-joins via explicit ON conditions and natural joins were formalized in the SQL-92 standard (ISO/IEC 9075:1992), which introduced structured join syntax to replace older, less readable theta-join notations in the WHERE clause.[21] The natural join's implicitness has sparked debate among practitioners for potentially obscuring intent, though it aligns with the standard's goal of concise relational algebra expression.[20]

Outer Joins

Left Outer Join

The left outer join, commonly referred to as a left join, is an SQL operation that retrieves all rows from the left-hand table (the first table specified in the FROM clause) along with the corresponding matching rows from the right-hand table based on a specified join condition. For any rows in the left table that lack a match in the right table, the result includes those rows with NULL values populated in all columns originating from the right table. This behavior ensures the completeness of the left table's data in the output, distinguishing it from an inner join, which excludes unmatched rows entirely.[22][23] The standard syntax for a left outer join follows the ANSI SQL-92 specification and is expressed as:SELECT column_list

FROM left_table

LEFT [OUTER] JOIN right_table

ON join_condition;

SELECT column_list

FROM left_table

LEFT [OUTER] JOIN right_table

ON join_condition;

OUTER keyword is optional in most SQL implementations and is frequently omitted, simplifying the clause to LEFT JOIN. The ON clause defines the matching condition, typically an equality between columns from the two tables, though other predicates are permitted. This syntax integrates seamlessly into the FROM clause of a SELECT statement, allowing for additional filtering via WHERE or aggregation in the broader query.[22][23]

In the resulting dataset, every row from the left table appears exactly once, with right-table columns either filled with matching values or padded with NULLs for non-matching cases—often termed "left orphans." This structure facilitates comprehensive reporting where the primary dataset (left table) must remain intact. For instance, consider sample tables Employees (with columns EmployeeID, Name, DepartmentID) and Departments (with DepartmentID, DepartmentName):

Employees:

| EmployeeID | Name | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 10 |

| 2 | Bob | 20 |

| 3 | Charlie | 10 |

| 4 | David | NULL |

| 5 | Eve | 30 |

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|

| 10 | HR |

| 20 | IT |

| 30 | Sales |

SELECT e.EmployeeID, e.Name, d.DepartmentName

FROM Employees e

LEFT JOIN Departments d

ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID;

SELECT e.EmployeeID, e.Name, d.DepartmentName

FROM Employees e

LEFT JOIN Departments d

ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID;

DepartmentName due to no matching department.[23][22]

Left outer joins are particularly useful for scenarios requiring the identification of unmatched records, such as listing all employees regardless of department assignment to detect unassigned staff. The operation's asymmetry underscores its directional nature: interchanging the left and right tables yields a right outer join, altering which table's rows are fully preserved and which receive NULL padding.[22]

Right Outer Join

The right outer join, also known as RIGHT JOIN or RIGHT OUTER JOIN, is a type of outer join in SQL that returns all rows from the right (second) table in the join operation, along with the matching rows from the left (first) table based on the specified join condition. For rows in the right table that have no corresponding match in the left table, NULL values are returned for all columns from the left table. This ensures that no data from the right table is excluded, making it useful for scenarios where the right table represents the primary dataset of interest.[5][4][16] The syntax for a right outer join follows the standard SQL JOIN clause format:SELECT column_list

FROM left_table

RIGHT OUTER JOIN right_table

ON join_condition;

SELECT column_list

FROM left_table

RIGHT OUTER JOIN right_table

ON join_condition;

RIGHT OUTER JOIN keywords can often be abbreviated as RIGHT JOIN, and the join condition is typically an equality comparison (equi-join) on one or more columns, though other conditions are possible. This syntax is part of the ANSI SQL-92 standard and replaced older proprietary outer join syntax used in some dialects, such as the = and = operators in early SQL Server versions.[1][16][4]

A right outer join is logically equivalent to a left outer join with the roles of the two tables reversed, allowing the same result to be achieved by swapping the table positions and using LEFT JOIN instead. This equivalence is why right outer joins are often avoided in practice, as left joins are more intuitive for left-to-right reading and promote consistency in query writing; developers typically rewrite right joins to use left joins by reordering tables.[3][4]

To illustrate, consider two sample tables: an Employees table with columns EmployeeID, Name, and DepartmentID, containing records for employees in departments 1, 2, and 3; and a Departments table with columns DepartmentID and DeptName, containing records for departments 1, 2, 3, and 4 (an extra department without employees). The query

SELECT e.Name, d.DeptName

FROM Employees e

RIGHT OUTER JOIN Departments d

ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID;

SELECT e.Name, d.DeptName

FROM Employees e

RIGHT OUTER JOIN Departments d

ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID;

Name column in department 4, resulting in four rows total. This demonstrates how the right table (Departments) fully preserves its rows, unlike an inner join which would exclude department 4.[5][16]

Right outer joins are employed in cases where the right table must be comprehensively represented, such as reporting on all departments (right table) including those without assigned employees (optional matches from the left table), ensuring complete coverage of the primary entity. They are less common than left outer joins due to the preference for restructuring queries, but remain valuable when the natural table order aligns with the right table as primary.[5]

Support for right outer joins is universal across modern relational database management systems (RDBMS), including SQL Server, Oracle Database, PostgreSQL, and MySQL, as they conform to the SQL:1999 standard and later revisions. Legacy systems may require alternative syntax like the older =* operator (for right outer joins) in early SQL Server versions, but explicit JOIN clauses are recommended for portability and clarity.[1][4][16][24]

Full Outer Join

The full outer join in SQL combines the results of an inner join with those of a left outer join and a right outer join, producing a result set that includes all rows from both participating tables, with NULL values inserted in places where there is no matching data from the other table.[25][6] This operation ensures that no rows are excluded due to the lack of a match, making it useful for comprehensive data merging.[1] Introduced as part of the ANSI SQL-92 standard, it provides a standardized way to handle outer joins across compliant database systems.[26] The syntax for a full outer join follows the SQL-92 join clause format:SELECT columns

FROM table1

FULL OUTER JOIN table2

ON join_condition;

SELECT columns

FROM table1

FULL OUTER JOIN table2

ON join_condition;

FULL JOIN.[25][6] The ON clause specifies the join condition, typically an equality between columns from the two tables, though other predicates are allowed.[1]

In the result set, rows where data matches the join condition appear with complete information from both tables, similar to an inner join. Unmatched rows from the left table include all columns from the left table populated and NULLs for the right table's columns, while unmatched rows from the right table have NULLs for the left table's columns and full data from the right.[25] This dual inclusion of "orphaned" rows distinguishes it from inner joins, which discard non-matches, and from left or right outer joins, which retain orphans from only one side.[6]

Consider sample tables Employees and Departments. The Employees table might contain:

| EmployeeID | Name | DepartmentID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | 101 |

| 2 | Bob | 102 |

| 3 | Charlie | NULL |

Departments table might contain:

| DepartmentID | DepartmentName |

|---|---|

| 101 | HR |

| 102 | IT |

| 103 | Finance |

SELECT e.EmployeeID, e.Name, d.DepartmentID, d.DepartmentName FROM Employees e FULL OUTER JOIN Departments d ON e.DepartmentID = d.DepartmentID; yields four rows: two matched pairs (Alice-HR, Bob-IT), one unmatched employee (Charlie with NULL department details), and one unmatched department (Finance with NULL employee details).[27]

Full outer joins are commonly used in data reconciliation scenarios, such as identifying differences between two datasets or merging customer records from disparate sources to ensure completeness without losing unique entries. However, not all database management systems support full outer joins natively; for instance, MySQL lacks direct support and requires a workaround using a UNION of left and right joins, despite the SQL-92 standard.[28][29]

Special Join Types

Self-Join

A self-join is a join operation in which a single table is joined with itself to compare or relate rows within that table.[1] This requires referencing the table twice in the FROM clause, once as the left table and once as the right table, using distinct aliases to qualify column names and avoid ambiguity.[30] For instance, the clause might appear asFROM employees e1 JOIN employees e2.[1]

Self-joins are commonly applied to hierarchical data, such as employee-manager relationships where a foreign key in the table points to another row in the same table; to identify duplicate rows by matching identical values across columns; or to conduct intra-table comparisons, like finding pairs of records that satisfy relative conditions.[4] In the employee-manager scenario, the join links subordinates to their supervisors based on a ManagerID column that references the EmployeeID primary key.[30]

The syntax for a basic inner self-join mirrors that of a standard inner join, specifying the join condition in the ON clause to match rows between the aliased instances. Consider this example:

SELECT e1.name AS employee_name, e2.name AS manager_name

FROM employees e1

JOIN employees e2 ON e1.manager_id = e2.employee_id;

SELECT e1.name AS employee_name, e2.name AS manager_name

FROM employees e1

JOIN employees e2 ON e1.manager_id = e2.employee_id;

| EmployeeID | Name | ManagerID |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | NULL |

| 2 | Bob | 1 |

| 3 | Charlie | 1 |

| 4 | David | 2 |

Handling NULL Values

In SQL, predicates involving NULL values operate under a three-valued logic system, where results can be TRUE, FALSE, or UNKNOWN, as defined in the ANSI/ISO SQL standard to handle missing or inapplicable data.[31] This logic propagates through comparisons: any equality or inequality operation with NULL (e.g.,column = NULL or column <> NULL) evaluates to UNKNOWN rather than TRUE or FALSE, since NULL represents an unknown value that cannot be definitively matched.[32] Joins inherit this behavior in their ON clauses, treating UNKNOWN as non-matching, which excludes rows from the result set unless explicitly handled.[31]

For inner joins, a NULL in the join condition causes the entire predicate to evaluate to UNKNOWN, resulting in the exclusion of those rows from the output, as inner joins only include matched pairs.[33] Consider two sample tables: Employees (columns: EmpID, Name, DeptID) with rows including (1, 'Alice', 10), (2, 'Bob', NULL), and (3, 'Charlie', 20); and Departments (columns: DeptID, DeptName) with rows (10, 'HR') and (20, 'IT'). An inner join on Employees.DeptID = Departments.DeptID yields only Alice and Charlie, excluding Bob because NULL = 10 (or any value) is UNKNOWN.[34]

In outer joins, NULL values from non-matching rows are preserved in the result set for the columns of the table without a match, but a NULL in the ON condition still prevents matching and treats the row as unmatched. Using the same tables, a left outer join on Employees.DeptID = Departments.DeptID includes all employees: Alice with 'HR', Charlie with 'IT', and Bob with NULL for DeptName, preserving the unmatched row while filling non-matching columns with NULL.[33] However, if the ON condition itself involves a NULL (e.g., due to a computed value), the row is treated as non-matching regardless of outer join type.[32]

Best practices for handling NULLs in joins emphasize explicit checks to avoid unintended exclusions. Use IS NULL or IS NOT NULL operators in the ON clause or WHERE to target NULLs directly, as they evaluate to TRUE or FALSE without invoking UNKNOWN (e.g., ON e.DeptID = d.DeptID OR (e.DeptID IS NULL AND d.DeptID IS NULL) to match NULL-to-NULL).[33] The COALESCE function provides defaults by returning the first non-NULL value in a list (e.g., ON COALESCE(e.DeptID, 0) = COALESCE(d.DeptID, 0)), though this may alter semantics and impact performance by making conditions non-SARGable (search argument able), preventing index use.[34]

DBMS implementations vary from ANSI SQL standards, affecting NULL handling in joins. Oracle treats empty strings ('') as equivalent to NULL in comparisons, potentially excluding more rows in joins than expected under ANSI rules where empty strings are distinct. In contrast, SQL Server adheres more closely to ANSI NULL handling by default (via SET ANSI_NULLS ON), where = NULL always yields UNKNOWN, but allows legacy mode with SET ANSI_NULLS OFF to treat it as FALSE—though this is discouraged for portability.[35]

NULLs also introduce performance implications in joins, particularly when indexed. Nullable columns reduce index selectivity, as the optimizer must account for potential UNKNOWN results, leading to additional operations like row spools in queries involving NOT IN or outer joins, even if no actual NULLs exist.[36] Joining directly on NULLable columns without explicit handling can force table scans instead of index seeks, exacerbating costs on large datasets; filtered indexes excluding NULLs or adding NOT NULL constraints where possible mitigate this by improving cardinality estimates and plan efficiency.[34]

Alternatives to Joins

Subqueries as Alternatives

Subqueries in SQL consist of nested SELECT statements embedded within a main query, enabling the retrieval of data from multiple tables without explicitly using JOIN operations. These can appear in clauses such as WHERE, FROM, or SELECT, allowing the inner query's results to filter or provide values for the outer query. For example, consider two tables:employees (columns: id, name, department_id) and departments (columns: id, name). To find employee names in the HR department using a subquery:

SELECT name

FROM employees

WHERE department_id IN (

SELECT id

FROM departments

WHERE name = 'HR'

);

SELECT name

FROM employees

WHERE department_id IN (

SELECT id

FROM departments

WHERE name = 'HR'

);

employees contains rows like (1, 'Alice', 10) and (2, 'Bob', 20), and departments contains (10, 'HR') and (20, 'Sales'), this query returns 'Alice', equivalent to the inner join SELECT e.name FROM employees e INNER JOIN departments d ON e.department_id = d.id WHERE d.name = 'HR'.[37][38]

Subqueries prove useful for complex filtering scenarios, such as when a join might generate excessive intermediate rows before applying conditions, or when the logic involves dynamic or unknown result sets from the inner query. Non-correlated subqueries execute independently once, producing a result set that the outer query uses without dependency, making them suitable for straightforward aggregations or existence checks. In contrast, correlated subqueries reference columns from the outer query, executing repeatedly for each outer row, which suits row-by-row comparisons but increases computational overhead.[39][40][41]

While subqueries enhance readability for procedural-style logic or hierarchical data retrieval, they often underperform joins in efficiency, particularly correlated ones due to repeated executions. The SQL-92 standard expanded subquery capabilities, supporting their use in more clauses like SELECT lists and improving portability across compliant systems. However, modern database management systems frequently optimize subqueries by internally rewriting them as equivalent joins, leveraging join algorithms for better execution plans and reduced resource use.[38][42]

Set Operations like UNION

Set operations in SQL provide mechanisms to combine or compare result sets from multiple queries, serving as alternatives to joins when the goal is to merge rows vertically or identify overlaps and differences without relying on key-based matching between tables. These operators treat the outputs of SELECT statements as sets, requiring the queries to be union-compatible—meaning they must return the same number of columns with compatible data types in corresponding positions. Unlike joins, which pair columns across tables horizontally, set operations stack rows and perform set-theoretic manipulations, making them suitable for scenarios involving denormalized data or broad cross-table aggregations. The UNION operator concatenates the rows from two or more SELECT queries into a single result set, automatically eliminating duplicate rows to produce a distinct set. For instance, to compile a unique list of names from employees and department heads without joining the tables, one might use:SELECT name FROM employees

UNION

SELECT department_name FROM departments;

SELECT name FROM employees

UNION

SELECT department_name FROM departments;

Implementation

Join Algorithms

Database management systems employ various algorithms to execute SQL join operations efficiently, selecting the most appropriate one based on factors such as table sizes, available memory, data distribution, and whether the data is presorted or indexed. The primary algorithms include nested loop join, hash join, and sort-merge join, each optimized for different scenarios to minimize computational cost and I/O operations. The nested loop join is the simplest algorithm, iterating through each row of the outer relation and, for each row, scanning the inner relation to find matching rows based on the join condition. In its basic form, it performs a Cartesian product filtered by the condition, resulting in a worst-case time complexity of O(m * n), where m and n are the number of rows in the outer and inner relations, respectively. This approach is suitable for small tables or when the inner relation is indexed, allowing quick lookups instead of full scans, but it becomes inefficient for larger datasets due to repeated scans. Without a join condition, the nested loop join effectively computes a cross join. Hash join algorithms build a hash table on the smaller relation (the build input) using the join attribute as the key, then probe this table with each row from the larger relation (the probe input) to find matches.[43] The average time complexity is O(m + n), assuming uniform hash distribution and sufficient memory to hold the hash table, making it highly efficient for equi-joins on unsorted, large relations.[43] However, it is memory-intensive and performs poorly with severe data skew, where many rows hash to the same bucket, leading to increased collisions and potential spills to disk.[44] Sort-merge join requires sorting both relations on the join attribute before merging them in a single pass, similar to merging two sorted lists. The time complexity is O((m + n) log (m + n)) due to the sorting phase, followed by a linear O(m + n) merge, making it effective for large datasets that are already sorted or when sorting cost is amortized across multiple operations. It handles non-equi joins well but incurs high initial costs if data is unsorted and can suffer from skew in the sorted order. To illustrate, consider two small tables: Employees (5 rows) and Departments (3 rows). A nested loop join would scan Departments 5 times, yielding O(15) operations, which is acceptable. For larger tables, say Employees (1 million rows) and Departments (100,000 rows), a hash join building on Departments and probing with Employees achieves near-linear performance, avoiding the quadratic cost of nested loops.[43] Query optimizers select among these algorithms using statistics on table sizes, cardinalities, and histograms to estimate costs, often employing dynamic programming to generate execution plans. For multi-table joins, plans can be structured as left-deep trees, where each join adds one new relation to the right of the previous result, or bushy trees, allowing more balanced parallelism but increasing enumeration complexity. Left-deep trees are common for pipelining, while bushy trees benefit shared-nothing architectures by enabling independent subplan execution. Modern extensions include hybrid hash joins, which adapt to limited memory by partitioning the build relation and keeping one partition in memory while spilling others to disk, ensuring graceful degradation without full repartitioning.[45] The GRACE hash join, a partitioned variant, further enhances scalability in parallel environments by distributing buckets across processors.[43]Join Indexes and Optimization

Join indexes are specialized data structures designed to accelerate SQL join operations by providing efficient access paths to join columns or precomputing join results. In database systems like Teradata, a join index materializes the results of joins across multiple tables, allowing queries to retrieve pre-joined data directly rather than performing runtime joins, which is particularly beneficial for aggregations and frequent multi-table accesses.[46] Composite or bitmap indexes on foreign key columns, such as a composite index on(DepartmentID, EmployeeID) in an Employees table, enable faster lookups during joins by avoiding full table scans and supporting selective probing.

The query optimizer enhances join performance through cost-based analysis, selecting the most efficient join order, method, and access paths based on gathered statistics like row counts, cardinality estimates, and data distribution. For instance, optimizers in SQL Server and Oracle prioritize joining smaller tables to larger ones first to minimize intermediate result sizes, leveraging heuristics and dynamic programming to evaluate possible orders.[47] Techniques such as predicate pushdown apply filters early in the join process to reduce the volume of data processed, while materialized views cache results of complex, repeated joins for direct access in subsequent queries.[48] Foreign key constraints further aid optimization by informing the optimizer of referential integrity, enabling it to prune unnecessary searches and assume valid join paths.[5]

For analytical workloads involving large datasets, columnstore indexes optimize joins by organizing data in columnar format, which supports batch-mode execution and achieves up to 100 times better performance compared to traditional rowstore indexes through reduced I/O and compression ratios up to 10:1.[49] An example is creating an index on the DepartmentID column in an Employees table:

CREATE INDEX IX_Employees_DepartmentID ON Employees (DepartmentID);

CREATE INDEX IX_Employees_DepartmentID ON Employees (DepartmentID);