Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cartesian product

View on Wikipedia

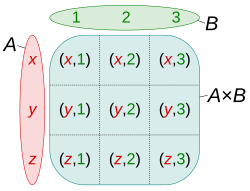

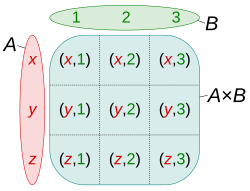

In mathematics, specifically set theory, the Cartesian product of two sets A and B, denoted A × B, is the set of all ordered pairs (a, b) where a is an element of A and b is an element of B.[1] In terms of set-builder notation, that is [2][3]

A table can be created by taking the Cartesian product of a set of rows and a set of columns. If the Cartesian product rows × columns is taken, the cells of the table contain ordered pairs of the form (row value, column value).[4]

One can similarly define the Cartesian product of n sets, also known as an n-fold Cartesian product, which can be represented by an n-dimensional array, where each element is an n-tuple. An ordered pair is a 2-tuple or couple. More generally still, one can define the Cartesian product of an indexed family of sets.

The Cartesian product is named after René Descartes,[5] whose formulation of analytic geometry gave rise to the concept, which is further generalized in terms of direct product.

Set-theoretic definition

[edit]A rigorous definition of the Cartesian product requires a domain to be specified in the set-builder notation. In this case the domain would have to contain the Cartesian product itself. For defining the Cartesian product of the sets and , with the typical Kuratowski's definition of a pair as , an appropriate domain is the set where denotes the power set. Then the Cartesian product of the sets and would be defined as[6]

Examples

[edit]A deck of cards

[edit]

An illustrative example is the standard 52-card deck. The standard playing card ranks {A, K, Q, J, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2} form a 13-element set. The card suits {♠, ♥, ♦, ♣} form a four-element set. The Cartesian product of these sets returns a 52-element set consisting of 52 ordered pairs, which correspond to all 52 possible playing cards.

Ranks × Suits returns a set of the form {(A, ♠), (A, ♥), (A, ♦), (A, ♣), (K, ♠), ..., (3, ♣), (2, ♠), (2, ♥), (2, ♦), (2, ♣)}.

Suits × Ranks returns a set of the form {(♠, A), (♠, K), (♠, Q), (♠, J), (♠, 10), ..., (♣, 6), (♣, 5), (♣, 4), (♣, 3), (♣, 2)}.

These two sets are distinct, even disjoint, but there is a natural bijection between them, under which (3, ♣) corresponds to (♣, 3) and so on.

A two-dimensional coordinate system

[edit]

The main historical example is the Cartesian plane in analytic geometry. In order to represent geometrical shapes in a numerical way, and extract numerical information from shapes' numerical representations, René Descartes assigned to each point in the plane a pair of real numbers, called its coordinates. Usually, such a pair's first and second components are called its x and y coordinates, respectively (see picture). The set of all such pairs (i.e., the Cartesian product , with denoting the real numbers) is thus assigned to the set of all points in the plane.[7]

Most common implementation (set theory)

[edit]A formal definition of the Cartesian product from set-theoretical principles follows from a definition of ordered pair. The most common definition of ordered pairs, Kuratowski's definition, is . Under this definition, is an element of , and is a subset of that set, where represents the power set operator. Therefore, the existence of the Cartesian product of any two sets in ZFC follows from the axioms of pairing, union, power set, and specification. Since functions are usually defined as a special case of relations, and relations are usually defined as subsets of the Cartesian product, the definition of the two-set Cartesian product is necessarily prior to most other definitions.

Non-commutativity and non-associativity

[edit]Let A, B, and C be sets.

The Cartesian product A × B is not commutative, [4] because the ordered pairs are reversed unless at least one of the following conditions is satisfied:[8]

- A is equal to B, or

- A or B is the empty set.

For example:

- A = {1,2}; B = {3,4}

- A × B = {1,2} × {3,4} = {(1,3), (1,4), (2,3), (2,4)}

- B × A = {3,4} × {1,2} = {(3,1), (3,2), (4,1), (4,2)}

- A = B = {1,2}

- A × B = B × A = {1,2} × {1,2} = {(1,1), (1,2), (2,1), (2,2)}

- A = {1,2}; B = ∅

- A × B = {1,2} × ∅ = ∅

- B × A = ∅ × {1,2} = ∅

Strictly speaking, the Cartesian product is not associative (unless one of the involved sets is empty). If for example A = {1}, then (A × A) × A = {((1, 1), 1)} ≠ {(1, (1, 1))} = A × (A × A).

Intersections, unions, and subsets

[edit]A = [1,4], B = [2,5], and

C = [4,7], demonstrating

A × (B∩C) = (A×B) ∩ (A×C),

A × (B∪C) = (A×B) ∪ (A×C), and

A = [2,5], B = [3,7],

C = [1,3],

D = [2,4], demonstrating

The Cartesian product satisfies the following property with respect to intersections (see middle picture).

In most cases, the above statement is not true if we replace intersection with union (see rightmost picture).

In fact, we have that:

For the set difference, we also have the following identity:

Here are some rules demonstrating distributivity with other operators (see leftmost picture):[8] where denotes the absolute complement of A.

Other properties related with subsets are:

Cardinality

[edit]The cardinality of a set is the number of elements of the set. For example, defining two sets: A = {a, b} and B = {5, 6}. Both set A and set B consist of two elements each. Their Cartesian product, written as A × B, results in a new set which has the following elements:

- A × B = {(a,5), (a,6), (b,5), (b,6)}.

where each element of A is paired with each element of B, and where each pair makes up one element of the output set. The number of values in each element of the resulting set is equal to the number of sets whose Cartesian product is being taken; 2 in this case. The cardinality of the output set is equal to the product of the cardinalities of all the input sets. That is,

- |A × B| = |A| · |B|.[4]

In this case, |A × B| = 4

Similarly,

- |A × B × C| = |A| · |B| · |C|

and so on.

The set A × B is infinite if either A or B is infinite, and the other set is not the empty set.[10]

Cartesian products of several sets

[edit]n-ary Cartesian product

[edit]The Cartesian product can be generalized to the n-ary Cartesian product over n sets X1, ..., Xn as the set

of n-tuples. If tuples are defined as nested ordered pairs, it can be identified with (X1 × ... × Xn−1) × Xn. If a tuple is defined as a function on {1, 2, ..., n} that takes its value at i to be the i-th element of the tuple, then the Cartesian product X1 × ... × Xn is the set of functions

Cartesian nth power

[edit]The Cartesian square of a set X is the Cartesian product X2 = X × X. An example is the 2-dimensional plane R2 = R × R where R is the set of real numbers:[1] R2 is the set of all points (x,y) where x and y are real numbers (see the Cartesian coordinate system).

The Cartesian nth power of a set X, denoted , can be defined as

An example of this is R3 = R × R × R, with R again the set of real numbers,[1] and more generally Rn.

The Cartesian nth power of a set X may be identified with the set of the functions mapping to X the n-tuples of elements of X. As a special case, the Cartesian 0th power of X is the singleton set, that has the empty function with codomain X as its unique element.

Intersections, unions, complements and subsets

[edit]Let Cartesian products be given and . Then

- , if and only if for all ;[11]

- , at the same time, if there exists at least one such that , then ;[11]

- , moreover, equality is possible only in the following cases:[12]

- or ;

- for all except for one from .

- The complement of a Cartesian product can be calculated,[12] if a universe is defined . To simplify the expressions, we introduce the following notation. Let us denote the Cartesian product as a tuple bounded by square brackets; this tuple includes the sets from which the Cartesian product is formed, e.g.:

- .

In n-tuple algebra (NTA),[12] such a matrix-like representation of Cartesian products is called a C-n-tuple.

With this in mind, the union of some Cartesian products given in the same universe can be expressed as a matrix bounded by square brackets, in which the rows represent the Cartesian products involved in the union:

- .

Such a structure is called a C-system in NTA.

Then the complement of the Cartesian product will look like the following C-system expressed as a matrix of the dimension :

- .

The diagonal components of this matrix are equal correspondingly to .

In NTA, a diagonal C-system , that represents the complement of a C-n-tuple , can be written concisely as a tuple of diagonal components bounded by inverted square brackets:

- .

This structure is called a D-n-tuple. Then the complement of the C-system is a structure , represented by a matrix of the same dimension and bounded by inverted square brackets, in which all components are equal to the complements of the components of the initial matrix . Such a structure is called a D-system and is calculated, if necessary, as the intersection of the D-n-tuples contained in it. For instance, if the following C-system is given:

- ,

then its complement will be the D-system

- .

Let us consider some new relations for structures with Cartesian products obtained in the process of studying the properties of NTA.[12] The structures defined in the same universe are called homotypic ones.

- The intersection of C-systems. Assume the homotypic C-systems are given and . Their intersection will yield a C-system containing all non-empty intersections of each C-n-tuple from with each C-n-tuple from .

- Checking the inclusion of a C-n-tuple into a D-n-tuple. For the C-n-tuple and the D-n-tuple holds , if and only if, at least for one holds .

- Checking the inclusion of a C-n-tuple into a D-system. For the C-n-tuple and the D-system is true , if and only if, for every D-n-tuple from holds .

Infinite Cartesian products

[edit]It is possible to define the Cartesian product of an arbitrary (possibly infinite) indexed family of sets. If I is any index set, and is a family of sets indexed by I, then the Cartesian product of the sets in is defined to be that is, the set of all functions defined on the index set I such that the value of the function at a particular index i is an element of Xi. Even if each of the Xi is nonempty, the Cartesian product may be empty if the axiom of choice, which is equivalent to the statement that every such product is nonempty, is not assumed. may also be denoted .[13]

For each j in I, the function defined by is called the j-th projection map.

Cartesian power is a Cartesian product where all the factors Xi are the same set X. In this case, is the set of all functions from I to X, and is frequently denoted XI. This case is important in the study of cardinal exponentiation. An important special case is when the index set is , the natural numbers: this Cartesian product is the set of all infinite sequences with the i-th term in its corresponding set Xi. For example, each element of can be visualized as a vector with countably infinite real number components. This set is frequently denoted , or .

Other forms

[edit]Abbreviated form

[edit]If several sets are being multiplied together (e.g., X1, X2, X3, ...), then some authors[14] choose to abbreviate the Cartesian product as simply ×Xi.

Cartesian product of functions

[edit]If f is a function from X to A and g is a function from Y to B, then their Cartesian product f × g is a function from X × Y to A × B with

This can be extended to tuples and infinite collections of functions. This is different from the standard Cartesian product of functions considered as sets.

Cylinder

[edit]Let be a set and . Then the cylinder of with respect to is the Cartesian product of and .

Normally, is considered to be the universe of the context and is left away. For example, if is a subset of the natural numbers , then the cylinder of is .

Definitions outside set theory

[edit]Category theory

[edit]Although the Cartesian product is traditionally applied to sets, category theory provides a more general interpretation of the product of mathematical structures. Product is the simplest example of categorical limit, where the indexing category is discrete. As category of sets can be identified with discrete categories and embedded this way as full subcategory of the diagrams indexing products can be reduced to indexing sets matching the set-theoretic definition.

Graph theory

[edit]In graph theory, the Cartesian product of two graphs G and H is the graph denoted by G × H, whose vertex set is the (ordinary) Cartesian product V(G) × V(H) and such that two vertices (u,v) and (u′,v′) are adjacent in G × H, if and only if u = u′ and v is adjacent with v′ in H, or v = v′ and u is adjacent with u′ in G. The Cartesian product of graphs is not a product in the sense of category theory. Instead, the categorical product is known as the tensor product of graphs.

See also

[edit]- Axiom of power set (to prove the existence of the Cartesian product)

- Direct product

- Empty product

- Finitary relation

- Join (SQL) § Cross join

- Orders on the Cartesian product of totally ordered sets

- Outer product

- Product (category theory)

- Product topology

- Product type

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric W. "Cartesian Product". MathWorld. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Warner, S. (1990). Modern Algebra. Dover Publications. p. 6.

- ^ Nykamp, Duane. "Cartesian product definition". Math Insight. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Cartesian Product". web.mnstate.edu. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "Cartesian". Merriam-Webster.com. 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Corry, S. "A Sketch of the Rudiments of Set Theory" (PDF). Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Goldberg, Samuel (1986). Probability: An Introduction. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Corporation. p. 41. ISBN 9780486652528.

- ^ a b Singh, S. (August 27, 2009). Cartesian product. Retrieved from the Connexions Web site: http://cnx.org/content/m15207/1.5/

- ^ Cartesian Product of Subsets. (February 15, 2011). ProofWiki. Retrieved 05:06, August 1, 2011 from https://proofwiki.org/w/index.php?title=Cartesian_Product_of_Subsets&oldid=45868

- ^ Peter S. (1998). A Crash Course in the Mathematics of Infinite Sets. St. John's Review, 44(2), 35–59. Retrieved August 1, 2011, from http://www.mathpath.org/concepts/infinity.htm

- ^ a b Bourbaki, N. (2006). Théorie des ensembles. Springer. pp. E II.34– E II.38.

- ^ a b c d Kulik, B.; Fridman, A. (2022). Complicated Methods of Logical Analysis Based on Simple Mathematics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-8014-5.

- ^ F. R. Drake, Set Theory: An Introduction to Large Cardinals, p. 24. Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, vol. 76 (1978). ISBN 0-7204-2200-0.

- ^ Osborne, M., and Rubinstein, A., 1994. A Course in Game Theory. MIT Press.

External links

[edit]Cartesian product

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Notation

Set-theoretic definition

In set theory, the Cartesian product of two sets and , denoted , is defined as the set of all ordered pairs such that and . This operation combines elements from each set to form a new set whose members are these pairs, providing a foundational structure for representing relations and functions between sets.[7] Formally, the definition is expressed as An ordered pair differs fundamentally from an unordered pair , as the former preserves the sequence of elements— if and only if and —while the latter does not distinguish order, so . In axiomatic set theory, ordered pairs can be constructed using the Kuratowski definition, , or using the Hausdorff definition, , where 1 and 2 are distinct objects different from a and b, both of which encode order using only sets without assuming pairs as primitives.[8][9] The concept originated with René Descartes in the 17th century, who introduced it through his development of analytic geometry to pair algebraic equations with geometric points via coordinates.[10]Standard notation and abbreviations

The standard notation for the Cartesian product of two sets and in set theory is , where the symbol represents the cross product operation. This notation emphasizes the formation of ordered pairs from elements of the respective sets.[11] For products involving multiple sets indexed by a set , the abbreviated form or is commonly used, particularly when the index set is finite or specified explicitly to avoid ambiguity in chaining binary products. This indexed notation allows for a compact representation of the set of all functions such that for each . In mathematics, the symbol remains the conventional choice for denoting Cartesian products of sets. In computer science, however, subtle variations appear in the context of product types for data structures; for instance, functional programming languages like Standard ML use the asterisk to denote product types, as inint * bool. (Note: This citation references Pierce's "Types and Programming Languages," a seminal work on type systems, where product types are discussed, aligning with notations like those in ML-family languages.)

The empty product, or Cartesian product over an empty index set, is defined as the singleton set containing the empty tuple, , which serves as the identity element for the Cartesian product operation in set theory.[12] This convention ensures consistency in the recursive definition of products, where the nullary case yields a unique "empty" choice.[12]

Examples

Deck of cards

A standard deck of playing cards provides a concrete illustration of the Cartesian product in set theory. The set of suits consists of four elements: hearts, diamonds, clubs, and spades.[13] The set of ranks includes thirteen elements: ace, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, jack, queen, and king.[1][13] The deck itself is the Cartesian product of these sets, denoted as , where is the set of suits and is the set of ranks.[13][14] Each card in the deck corresponds to a unique ordered pair , with the suit appearing first by convention to specify the card's identity, such as for the ace of hearts.[15] This ordered pair structure ensures that no two cards share the same combination, distinguishing, for example, the ace of hearts from the ace of spades.[1][13] To visualize a portion of this product, consider the following partial table for the suits hearts and diamonds crossed with the ranks ace through 3:| Suit / Rank | Ace | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hearts | |||

| Diamonds |

![{\displaystyle (A\times C)\cup (B\times D)=[(A\setminus B)\times C]\cup [(A\cap B)\times (C\cup D)]\cup [(B\setminus A)\times D]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/67cfa315894265914c23ed2d555d05e6255d98a4)

![{\displaystyle (A\times C)\setminus (B\times D)=[A\times (C\setminus D)]\cup [(A\setminus B)\times C]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/401c029889c8cdaaa16d20a38c311158b98cfd41)

![{\displaystyle A=A_{1}\times A_{2}\times \dots \times A_{n}=[A_{1}\quad A_{2}\quad \dots \quad A_{n}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f263e27a488d5c2b133c1511ac31c0742b54937)

![{\displaystyle A\cup B=(A_{1}\times A_{2}\times \dots \times A_{n})\cup (B_{1}\times B_{2}\times \dots \times B_{n})=\left[{\begin{array}{cccc}A_{1}&A_{2}&\dots &A_{n}\\B_{1}&B_{2}&\dots &B_{n}\end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4bc8ec1086612b829272b95bb0ddb3ee54fba7a1)

![{\displaystyle A^{\complement }=\left[{\begin{array}{ccccc}A_{1}^{\complement }&X_{2}&\dots &X_{n-1}&X_{n}\\X_{1}&A_{2}^{\complement }&\dots &X_{n-1}&X_{n}\\\dots &\dots &\dots &\dots &\dots \\X_{1}&X_{2}&\dots &A_{n-1}^{\complement }&X_{n}\\X_{1}&X_{2}&\dots &X_{n-1}&A_{n}^{\complement }\end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1872e97a8f0ed419fe732d9e81da248057d7401)

![{\displaystyle A^{\complement }=]A_{1}^{\complement }\quad A_{2}^{\complement }\quad \dots \quad A_{n}^{\complement }[}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a913f7ef1e9150299787df629e9daefeace55f08)

![{\displaystyle R_{1}=\left[{\begin{array}{cccc}A_{1}&A_{2}&\dots &A_{n}\\B_{1}&B_{2}&\dots &B_{n}\end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f8707632efacd6f90bf7e6412c58f60b92256164)

![{\displaystyle R_{1}^{\complement }=\left]{\begin{array}{cccc}A_{1}^{\complement }&A_{2}^{\complement }&\dots &A_{n}^{\complement }\\B_{1}^{\complement }&B_{2}^{\complement }&\dots &B_{n}^{\complement }\end{array}}\right[}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d2cb4acf40aa40bc7ca0b187501922b0691f319d)

![{\displaystyle P=[P_{1}\quad P_{2}\quad \cdots \quad P_{N}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1990bbdbf2f5b6f9d8a4136c28a52bdc919d7c73)

![{\displaystyle Q=]Q_{1}\quad Q_{2}\quad \cdots \quad Q_{N}[}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2e24a3c1abe35d23b1ae203c96c653eb496b5081)