Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Input/output

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

| Operating systems |

|---|

|

| Common features |

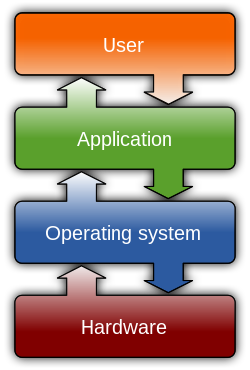

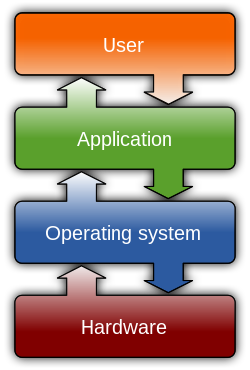

In computing, input/output (I/O, i/o, or informally io or IO) is the communication between an information processing system, such as a computer, and the outside world, such as another computer system, peripherals, or a human operator. Inputs are the signals or data received by the system and outputs are the signals or data sent from it. The term can also be used as part of an action; to "perform I/O" is to perform an input or output operation.

I/O devices are the pieces of hardware used by a human (or other system) to communicate with a computer. For instance, a keyboard or computer mouse is an input device for a computer, while monitors and printers are output devices. Devices for communication between computers, such as modems and network cards, typically perform both input and output operations. Any interaction with the system by an interactor is an input and the reaction the system responds is called the output.

The designation of a device as either input or output depends on perspective. Mice and keyboards take physical movements that the human user outputs and convert them into input signals that a computer can understand; the output from these devices is the computer's input. Similarly, printers and monitors take signals that computers output as input, and they convert these signals into a representation that human users can understand. From the human user's perspective, the process of reading or seeing these representations is receiving output; this type of interaction between computers and humans is studied in the field of human–computer interaction. A further complication is that a device traditionally considered an input device, e.g., card reader, keyboard, may accept control commands to, e.g., select stacker, display keyboard lights, while a device traditionally considered as an output device may provide status data (e.g., low toner, out of paper, paper jam).

In computer architecture, the combination of the CPU and main memory, to which the CPU can read or write directly using individual instructions, is considered the brain of a computer. Any transfer of information to or from the CPU/memory combo, for example by reading data from a disk drive, is considered I/O.[1] The CPU and its supporting circuitry may provide memory-mapped I/O that is used in low-level computer programming, such as in the implementation of device drivers, or may provide access to I/O channels. An I/O algorithm is one designed to exploit locality and perform efficiently when exchanging data with a secondary storage device, such as a disk drive.

Interface

[edit]An I/O interface is required whenever the I/O device is driven by a processor. Typically a CPU communicates with devices via a bus. The interface must have the necessary logic to interpret the device address generated by the processor. Handshaking should be implemented by the interface using appropriate commands (like BUSY, READY, and WAIT), and the processor can communicate with an I/O device through the interface. If different data formats are being exchanged, the interface must be able to convert serial data to parallel form and vice versa. Because it would be a waste for a processor to be idle while it waits for data from an input device there must be provision for generating interrupts[2] and the corresponding type numbers for further processing by the processor if required.[clarification needed]

A computer that uses memory-mapped I/O accesses hardware by reading and writing to specific memory locations, using the same assembly language instructions that computer would normally use to access memory. An alternative method is via instruction-based I/O which requires that a CPU have specialized instructions for I/O.[1] Both input and output devices have a data processing rate that can vary greatly.[2] With some devices able to exchange data at very high speeds direct access to memory (DMA) without the continuous aid of a CPU is required.[2]

Higher-level implementation

[edit]Higher-level operating system and programming facilities employ separate, more abstract I/O concepts and primitives. For example, most operating systems provide application programs with the concept of files. Most programming languages provide I/O facilities either as statements in the language or as functions in a standard library for the language.

An alternative to special primitive functions is the I/O monad, which permits programs to just describe I/O, and the actions are carried out outside the program. This is notable because the I/O functions would introduce side-effects to any programming language, but this allows purely functional programming to be practical.

The I/O facilities provided by operating systems may be record-oriented, with files containing records, or stream-oriented, with the file containing a stream of bytes.

Channel I/O

[edit]Channel I/O requires the use of instructions that are specifically designed to perform I/O operations. The I/O instructions address the channel or the channel and device; the channel asynchronously accesses all other required addressing and control information. This is similar to DMA, but more flexible.

Port-mapped I/O

[edit]Port-mapped I/O also requires the use of special I/O instructions. Typically one or more ports are assigned to the device, each with a special purpose. The port numbers are in a separate address space from that used by normal instructions.

Direct memory access

[edit]Direct memory access (DMA) is a means for devices to transfer large chunks of data to and from memory independently of the CPU.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Null, Linda; Julia Lobur (2006). The Essentials of Computer Organization and Architecture. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 185. ISBN 0763737690. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Abd-El-Barr, Mostafa; Hesham El-Rewini (2005). Fundamentals of Computer Organization and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 161–162. ISBN 9780471478331. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

External links

[edit] Media related to Input/output at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Input/output at Wikimedia Commons

Input/output

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Input/output (I/O) refers to the communication between a computer system and the external world, encompassing the transfer of data into the system (input) or out of the system (output) to enable interaction with peripherals and networks.[3] This process is fundamental to computing, as it allows programs to receive inputs from devices such as keyboards, mice, sensors, or network interfaces and produce outputs on displays, printers, speakers, or storage media like hard disk drives and solid-state drives. Without effective I/O mechanisms, computers would be isolated from their environment, limiting their utility beyond isolated computation.[3] Historically, I/O began in the 1950s with batch processing systems that relied on punched cards for data and program input, as seen in early IBM machines where operators submitted jobs in offline batches to minimize setup times and maximize machine utilization.[8] These systems evolved in the 1960s toward time-sharing and interactive computing, enabling multiple users to access I/O resources concurrently through terminals, which shifted from rigid batch queues to real-time responsiveness and supported the growth of personal computing.[9] I/O plays a critical role in system performance, often acting as a primary bottleneck where the speed of data transfer lags behind CPU processing capabilities, leading to substantial idle CPU time in I/O-bound workloads, such as 50% as the processor waits for device completion.[10] For instance, in scientific and data-intensive applications, I/O demands can dominate execution, shifting bottlenecks from computational FLOPS to IOPS and necessitating optimizations like direct memory access to bypass CPU involvement in bulk transfers.[11] I/O devices are classified by their interaction style and data handling: human-readable devices, such as monitors and printers, facilitate user communication, while machine-readable ones, like disk drives and tapes, exchange data between systems.[12] Additionally, devices are categorized as block-oriented, which manage fixed-size data blocks (e.g., hard drives supporting seek operations for efficient random access), or character-oriented, which handle streams of individual bytes without inherent structure (e.g., keyboards or terminals).[12]Synchronous vs. Asynchronous I/O

In synchronous I/O, also referred to as blocking I/O, the central processing unit (CPU) initiates an input/output operation and suspends execution of the calling process until the operation completes or fails. This model ensures sequential control flow, where the process cannot proceed to subsequent instructions until the I/O request is resolved, such as when data is read from a device or written to storage. A canonical example is the POSIXread() function, which attempts to transfer a specified number of bytes from an open file descriptor into a buffer and blocks the caller if the data is not immediately available.[13] This approach simplifies programming by guaranteeing that the operation's outcome is available immediately upon return from the system call, but it leads to inefficiency when dealing with slow peripheral devices like disks or networks, as the CPU remains idle during the wait.[14]

Asynchronous I/O, or non-blocking I/O, contrasts by allowing the CPU to continue executing other tasks immediately after submitting an I/O request, with the operation proceeding in the background without halting the calling process. Completion is determined later through mechanisms such as polling for status, callbacks, or signals, enabling higher resource utilization. In the POSIX standard, functions like aio_read() exemplify this by queuing a read request—specifying the file descriptor, buffer, byte count, and offset—and returning control to the application right away; the process can then check completion using aio_error() or receive notification via the SIGIO signal if enabled.[15] Asynchronous models often rely on hardware support, such as interrupt-driven I/O, to signal the CPU upon operation finish without constant polling.[16]

Synchronous I/O offers advantages in simplicity and predictability, making it suitable for applications where operations are quick or order is critical, but it suffers from poor scalability under high latency, as each blocking call ties up the CPU thread. Asynchronous I/O improves efficiency for latency-bound tasks by overlapping computation and I/O, though it introduces complexity in managing completion states and potential race conditions, with overhead from queuing and notification that may outweigh benefits for short operations.[14] In benchmarks on storage systems, asynchronous approaches have demonstrated significantly higher throughput for concurrent workloads compared to synchronous ones, albeit sometimes at the cost of per-operation latency due to prioritization in kernel handling.[17]

| Aspect | Synchronous I/O | Asynchronous I/O |

|---|---|---|

| Latency | Higher for slow devices (CPU blocks fully) | Lower effective latency (CPU proceeds; completion deferred) |

| Throughput | Lower in concurrent scenarios (threads idle per operation) | Higher for multiple overlapping requests (e.g., servers handling thousands of connections) |

| Use Cases | Simple scripts, small file reads where operations are fast and sequential | High-concurrency servers, real-time data streaming, or I/O-intensive applications like web proxies |

Hardware Mechanisms

Programmed I/O

Programmed I/O, also known as polled I/O, is the simplest form of input/output operation where the central processing unit (CPU) directly manages data transfer by repeatedly checking the status of an I/O device through software loops.[20] In this method, the CPU executes instructions to read from or write to device registers, typically using specialized instructions such as IN and OUT in x86 architectures, to poll status flags and transfer data one byte at a time.[21] This approach requires no dedicated hardware beyond the device's control registers, making it suitable for basic systems where the CPU can afford to dedicate cycles to I/O tasks.[22] The process begins with device initialization, followed by a polling loop to monitor readiness, data transfer upon confirmation, and error handling if needed. For example, when polling a serial port for input, the CPU first configures the port's control registers. It then enters a loop checking a "data ready" flag in the status register. Once set, the CPU reads the data byte using an input instruction and clears the flag if required. Pseudocode for this serial port polling might appear as follows:initialize_serial_port(); // Set baud rate, enable receiver, etc.

while (more_data_needed) {

while (!(status_register & DATA_READY_FLAG)) { // Poll until data is ready

// CPU busy-waits here

}

data_byte = input_from_port(PORT_ADDRESS); // Read byte using IN instruction

process_data(data_byte); // Handle the received byte

if (error_detected(status_register)) {

handle_error(); // Manage parity or overrun errors

}

}

initialize_serial_port(); // Set baud rate, enable receiver, etc.

while (more_data_needed) {

while (!(status_register & DATA_READY_FLAG)) { // Poll until data is ready

// CPU busy-waits here

}

data_byte = input_from_port(PORT_ADDRESS); // Read byte using IN instruction

process_data(data_byte); // Handle the received byte

if (error_detected(status_register)) {

handle_error(); // Manage parity or overrun errors

}

}

Interrupt-Driven I/O

Interrupt-driven I/O is a hardware mechanism that enables the CPU to respond to I/O events without continuous polling, by having devices signal the CPU via interrupts when they are ready for data transfer or report an error.[12] In this approach, the device controller asserts an interrupt signal on a dedicated line when an event occurs, prompting the CPU to temporarily halt its current execution, save the processor state, and transfer control to an interrupt service routine (ISR) via an entry in the interrupt vector table.[27] The ISR then handles the necessary data transfer or error processing before restoring the CPU state and resuming the interrupted program.[28] Hardware interrupts, the primary type used in I/O operations, can be classified as edge-triggered or level-triggered based on the signaling method.[29] Edge-triggered interrupts are generated by a voltage transition (rising or falling edge) on the interrupt line, suitable for events like key presses where a single pulse indicates the occurrence.[30] Level-triggered interrupts maintain a high voltage level on the line until the interrupt is acknowledged, allowing the CPU to detect persistent conditions such as ongoing data availability.[30] Software interrupts, in contrast, are initiated by the executing program—often through instructions like INT in x86 assembly—to request OS services, such as initiating an I/O operation via a system call that traps to kernel mode.[31] In architectures like x86, interrupts are routed through interrupt request (IRQ) lines connected to a programmable interrupt controller, which assigns priority levels to ensure higher-priority interrupts (e.g., hardware errors) are serviced before lower ones (e.g., disk completion).[28] The controller maps the IRQ to an entry in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT), a vector table in memory that stores the address and segment of the corresponding ISR.[28] Upon interrupt, the CPU performs a context switch by pushing the current program counter, flags, and registers onto the stack, enabling kernel-level execution in the ISR; upon completion, the IRET instruction restores this state.[29] To enhance efficiency, double-buffering may be employed, where the ISR transfers data to or from one buffer while the CPU or application processes the other, minimizing wait times during overlapping I/O and computation phases.[32] A representative example is keyboard input handling: when a key is pressed, the keyboard controller detects the scan code and asserts an IRQ (typically IRQ1 in x86 systems), triggering the ISR.[33] The ISR reads the scan code from the controller's data port, translates it to an ASCII character if needed, stores it in a system buffer, and signals the waiting process or enqueues it for later retrieval, after which the ISR acknowledges the interrupt and returns control to the CPU.[33] This method offers superior CPU utilization over polling by freeing the processor for other tasks during I/O latency periods, facilitating multitasking in operating systems like Unix where multiple processes can interleave execution around interrupt events.[12] However, it incurs overhead from frequent context switches and ISR invocations for each transfer, limiting scalability for high-frequency I/O compared to more autonomous techniques.[12] Historically, interrupt-driven I/O gained prominence in the 1970s with systems like the PDP-11 minicomputers, which introduced a vectored interrupt architecture with a 256-entry table for direct device-specific handler addressing, enhancing I/O throughput in early multitasking environments.[18] This approach underpins asynchronous I/O models, where programs initiate operations non-blockingly and handle completions via interrupts.[12]Memory Access Techniques

Port-Mapped I/O

Port-mapped I/O, also known as isolated I/O, is a technique where input/output devices are addressed using a dedicated address space separate from the main memory, accessed through specialized CPU instructions rather than standard memory operations. In the x86 architecture, this involves a 16-bit I/O address space supporting up to 65,536 ports, numbered from 0x0000 to 0xFFFF, which allows the CPU to communicate directly with peripheral devices without overlapping with memory addresses.[34] The IN instruction reads data from a specified port into a CPU register, such as AL for 8-bit operations or AX for 16-bit, while the OUT instruction writes data from a register to the port, with the port address provided either via the DX register or as an immediate value for ports below 256.[34] This separation ensures that I/O operations assert distinct control signals on the system bus, distinguishing them from memory accesses.[34] Hardware implementation relies on I/O controller chips or bridge circuitry that decode the 16-bit port address transmitted on the I/O bus, enabling selective activation of specific devices while ignoring irrelevant addresses. In x86 systems, the CPU generates dedicated I/O read (IOR#) and I/O write (IOW#) signals to facilitate this decoding, often requiring less complex logic compared to broader memory spaces due to the limited 64K port range. Devices may partially decode addresses, mapping multiple consecutive ports to the same register for compatibility, though this can lead to address conflicts if not managed carefully.[35] Common examples include legacy serial and parallel ports in PC architectures. The first serial port (COM1) is typically mapped to ports 0x3F8 (data), 0x3F9 (interrupt enable), 0x3FA (modem control), and others up to 0x3FF for status and control registers. Similarly, the parallel printer port (LPT1) uses ports 0x378 for data output, 0x379 for status input, and 0x37A for control, allowing direct byte transfers to printers or other peripherals. In software, such as the Linux kernel, port I/O is performed using inline assembly wrappers like outb(), which outputs an 8-bit value to a port; for instance, to send a byte to COM1's data register:outb(0x41, 0x3F8);. These functions, defined in <asm/io.h>, ensure privileged access and handle serialization for safe concurrent use.[36][35][37]

One key advantage of port-mapped I/O is the isolation of the I/O address space from memory, preventing inadvertent software access to devices during normal memory operations and simplifying protection mechanisms, as the operating system can grant user-mode access to specific ports with fine-grained control via instructions like IOPL in x86. Additionally, the smaller address space reduces decoding hardware complexity, making it suitable for early microprocessor designs.[38][39]

However, port-mapped I/O has notable disadvantages, including slower performance due to the overhead of special instructions, which are limited in operand flexibility—often restricted to accumulator registers like EAX—and cannot leverage the full range of memory addressing modes or caching optimizations available for memory accesses. The fixed 64K port limit also constrains scalability in systems with many devices, contributing to its status as a legacy mechanism in modern x86 architectures, where memory-mapped I/O predominates for unified addressing.[40][39] In contrast to memory-mapped I/O, port-mapped requires distinct instructions, avoiding shared address decoding but at the cost of integration with high-level memory operations.[34]

Memory-Mapped I/O

Memory-mapped I/O (MMIO) integrates input/output devices into the CPU's physical or virtual memory address space, enabling the processor to access device registers using the same load and store instructions employed for main memory operations. In this scheme, specific address ranges are reserved for I/O devices, and the hardware decodes these addresses to route transactions to the appropriate peripherals rather than to RAM. This unification simplifies the instruction set architecture by eliminating the need for dedicated I/O instructions, allowing standard memory access primitives like MOV in x86 or LDR in ARM to control devices.[3][41] The mechanism operates by assigning fixed memory addresses to device control, status, and data registers; for instance, a serial port's transmit buffer might be mapped to address 0x1000, where writing a byte via a store instruction sends data to the device. The memory management unit (MMU) or address decoder in the system bus plays a key role in implementation, distinguishing I/O addresses from memory ones through hardware logic, such as additional chip select signals or address range checks, without altering the CPU's core execution flow. This approach is particularly advantageous in reduced instruction set computing (RISC) architectures, where the absence of specialized I/O commands streamlines design and compiler optimization.[39][42] Practical examples abound in embedded systems and high-performance computing. In ARM-based microcontrollers, peripherals like UARTs or timers are routinely memory-mapped; a simple assembly code snippet to read a UART status register might appear as:LDR R0, =0x40002000 @ UART base address

LDR R1, [R0, #0x18] @ Offset for status register

LDR R0, =0x40002000 @ UART base address

LDR R1, [R0, #0x18] @ Offset for status register