Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

File system

View on Wikipedia| Operating systems |

|---|

|

| Common features |

In computing, a file system or filesystem (often abbreviated to FS or fs) governs file organization and access. A local file system is a capability of an operating system that services the applications running on the same computer.[1][2] A distributed file system is a protocol that provides file access between networked computers.

A file system provides a data storage service that allows applications to share mass storage. Without a file system, applications could access the storage in incompatible ways that lead to resource contention, data corruption and data loss.

There are many file system designs and implementations – with various structure and features and various resulting characteristics such as speed, flexibility, security, size and more.

File systems have been developed for many types of storage devices, including hard disk drives (HDDs), solid-state drives (SSDs), magnetic tapes and optical discs.[3]

A portion of the computer main memory can be set up as a RAM disk that serves as a storage device for a file system. File systems such as tmpfs can store files in virtual memory.

A virtual file system provides access to files that are either computed on request, called virtual files (see procfs and sysfs), or are mapping into another, backing storage.

Etymology

[edit]From c. 1900 and before the advent of computers the terms file system, filing system and system for filing were used to describe methods of organizing, storing and retrieving paper documents.[4] By 1961, the term file system was being applied to computerized filing alongside the original meaning.[5] By 1964, it was in general use.[6]

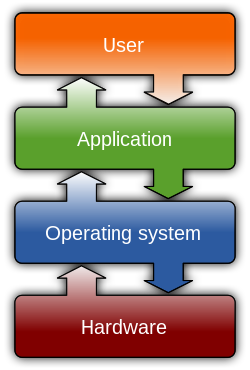

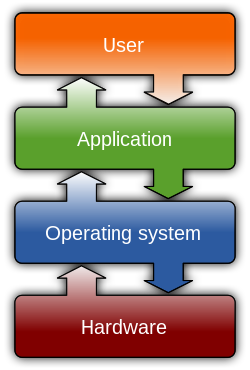

Architecture

[edit]A local file system's architecture can be described as layers of abstraction even though a particular file system design may not actually separate the concepts.[7]

The logical file system layer provides relatively high-level access via an application programming interface (API) for file operations including open, close, read and write – delegating operations to lower layers. This layer manages open file table entries and per-process file descriptors.[8] It provides file access, directory operations, security and protection.[7]

The virtual file system, an optional layer, supports multiple concurrent instances of physical file systems, each of which is called a file system implementation.[8]

The physical file system layer provides relatively low-level access to a storage device (e.g. disk). It reads and writes data blocks, provides buffering and other memory management and controls placement of blocks in specific locations on the storage medium. This layer uses device drivers or channel I/O to drive the storage device.[7]

Attributes

[edit]File names

[edit]A file name, or filename, identifies a file to consuming applications and in some cases users.

A file name is unique so that an application can refer to exactly one file for a particular name. If the file system supports directories, then generally file name uniqueness is enforced within the context of each directory. In other words, a storage can contain multiple files with the same name, but not in the same directory.

Most file systems restrict the length of a file name.

Some file systems match file names as case sensitive and others as case insensitive. For example, the names MYFILE and myfile match the same file for case insensitive, but different files for case sensitive.

Most modern file systems allow a file name to contain a wide range of characters from the Unicode character set. Some restrict characters such as those used to indicate special attributes such as a device, device type, directory prefix, file path separator, or file type.

Directories

[edit]File systems typically support organizing files into directories, also called folders, which segregate files into groups.

This may be implemented by associating the file name with an index in a table of contents or an inode in a Unix-like file system.

Directory structures may be flat (i.e. linear), or allow hierarchies by allowing a directory to contain directories, called subdirectories.

The first file system to support arbitrary hierarchies of directories was used in the Multics operating system.[9] The native file systems of Unix-like systems also support arbitrary directory hierarchies, as do, Apple's Hierarchical File System and its successor HFS+ in classic Mac OS, the FAT file system in MS-DOS 2.0 and later versions of MS-DOS and in Microsoft Windows, the NTFS file system in the Windows NT family of operating systems, and the ODS-2 (On-Disk Structure-2) and higher levels of the Files-11 file system in OpenVMS.

Metadata

[edit]In addition to data, the file content, a file system also manages associated metadata which may include but is not limited to:

- name

- size which may be stored as the number of blocks allocated or as a byte count

- when created, last accessed, last modified

- owner user and group

- access permissions

- file attributes such as whether the file is read-only, executable, etc.

- device type (e.g. block, character, socket, subdirectory, etc.)

A file system stores associated metadata separate from the content of the file.

Most file systems store the names of all the files in one directory in one place—the directory table for that directory—which is often stored like any other file. Many file systems put only some of the metadata for a file in the directory table, and the rest of the metadata for that file in a completely separate structure, such as the inode.

Most file systems also store metadata not associated with any one particular file. Such metadata includes information about unused regions—free space bitmap, block availability map—and information about bad sectors. Often such information about an allocation group is stored inside the allocation group itself.

Additional attributes can be associated on file systems, such as NTFS, XFS, ext2, ext3, some versions of UFS, and HFS+, using extended file attributes. Some file systems provide for user defined attributes such as the author of the document, the character encoding of a document or the size of an image.

Some file systems allow for different data collections to be associated with one file name. These separate collections may be referred to as streams or forks. Apple has long used a forked file system on the Macintosh, and Microsoft supports streams in NTFS. Some file systems maintain multiple past revisions of a file under a single file name; the file name by itself retrieves the most recent version, while prior saved version can be accessed using a special naming convention such as "filename;4" or "filename(-4)" to access the version four saves ago.

See comparison of file systems § Metadata for details on which file systems support which kinds of metadata.

Storage space organization

[edit]A local file system tracks which areas of storage belong to which file and which are not being used.

When a file system creates a file, it allocates space for data. Some file systems permit or require specifying an initial space allocation and subsequent incremental allocations as the file grows.

To delete a file, the file system records that the file's space is free; available to use for another file.

A local file system manages storage space to provide a level of reliability and efficiency. Generally, it allocates storage device space in a granular manner, usually multiple physical units (i.e. bytes). For example, in Apple DOS of the early 1980s, 256-byte sectors on 140 kilobyte floppy disk used a track/sector map.[citation needed]

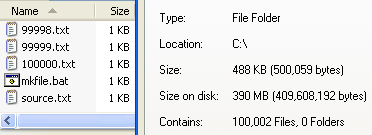

The granular nature results in unused space, sometimes called slack space, for each file except for those that have the rare size that is a multiple of the granular allocation.[10] For a 512-byte allocation, the average unused space is 256 bytes. For 64 KB clusters, the average unused space is 32 KB.

Generally, the allocation unit size is set when the storage is configured. Choosing a relatively small size compared to the files stored, results in excessive access overhead. Choosing a relatively large size results in excessive unused space. Choosing an allocation size based on the average size of files expected to be in the storage tends to minimize unusable space.

Fragmentation

[edit]

As a file system creates, modifies and deletes files, the underlying storage representation may become fragmented. Files and the unused space between files will occupy allocation blocks that are not contiguous.

A file becomes fragmented if space needed to store its content cannot be allocated in contiguous blocks. Free space becomes fragmented when files are deleted.[11]

Fragmentation is invisible to the end user and the system still works correctly. However, this can degrade performance on some storage hardware that works better with contiguous blocks such as hard disk drives. Other hardware such as solid-state drives are not affected by fragmentation.

Access control

[edit]A file system often supports access control of data that it manages.

The intent of access control is often to prevent certain users from reading or modifying certain files.

Access control can also restrict access by program in order to ensure that data is modified in a controlled way. Examples include passwords stored in the metadata of the file or elsewhere and file permissions in the form of permission bits, access control lists, or capabilities. The need for file system utilities to be able to access the data at the media level to reorganize the structures and provide efficient backup usually means that these are only effective for polite users but are not effective against intruders.

Methods for encrypting file data are sometimes included in the file system. This is very effective since there is no need for file system utilities to know the encryption seed to effectively manage the data. The risks of relying on encryption include the fact that an attacker can copy the data and use brute force to decrypt the data. Additionally, losing the seed means losing the data.

Storage quota

[edit]

Some operating systems allow a system administrator to enable disk quotas to limit a user's use of storage space.

Data integrity

[edit]A file system typically ensures that stored data remains consistent in both normal operations as well as exceptional situations like:

- accessing program neglects to inform the file system that it has completed file access (to close a file)

- accessing program terminates abnormally (crashes)

- media failure

- loss of connection to remote systems

- operating system failure

- system reset (soft reboot)

- power failure (hard reboot)

Recovery from exceptional situations may include updating metadata, directory entries and handling data that was buffered but not written to storage media.

Recording

[edit]A file system might record events to allow analysis of issues such as:

- file or systemic problems and performance

- nefarious access

Data access

[edit]Byte stream access

[edit]Many file systems access data as a stream of bytes. Typically, to read file data, a program provides a memory buffer and the file system retrieves data from the medium and then writes the data to the buffer. A write involves the program providing a buffer of bytes that the file system reads and then stores to the medium.

Record access

[edit]Some file systems, or layers on top of a file system, allow a program to define a record so that a program can read and write data as a structure; not an unorganized sequence of bytes.

If a fixed length record definition is used, then locating the nth record can be calculated mathematically, which is relatively fast compared to parsing the data for record separators.

An identification for each record, also known as a key, allows a program to read, write and update records without regard to their location in storage. Such storage requires managing blocks of media, usually separating key blocks and data blocks. Efficient algorithms can be developed with pyramid structures for locating records.[12]

Utilities

[edit]Typically, a file system can be managed by the user via various utility programs.

Some utilities allow the user to create, configure and remove an instance of a file system. It may allow extending or truncating the space allocated to the file system.

Directory utilities may be used to create, rename and delete directory entries, which are also known as dentries (singular: dentry),[13] and to alter metadata associated with a directory. Directory utilities may also include capabilities to create additional links to a directory (hard links in Unix), to rename parent links (".." in Unix-like operating systems),[clarification needed] and to create bidirectional links to files.

File utilities create, list, copy, move and delete files, and alter metadata. They may be able to truncate data, truncate or extend space allocation, append to, move, and modify files in-place. Depending on the underlying structure of the file system, they may provide a mechanism to prepend to or truncate from the beginning of a file, insert entries into the middle of a file, or delete entries from a file. Utilities to free space for deleted files, if the file system provides an undelete function, also belong to this category.

Some file systems defer operations such as reorganization of free space, secure erasing of free space, and rebuilding of hierarchical structures by providing utilities to perform these functions at times of minimal activity. An example is the file system defragmentation utilities.

Some of the most important features of file system utilities are supervisory activities which may involve bypassing ownership or direct access to the underlying device. These include high-performance backup and recovery, data replication, and reorganization of various data structures and allocation tables within the file system.

File system API

[edit]Utilities, libraries and programs use file system APIs to make requests of the file system. These include data transfer, positioning, updating metadata, managing directories, managing access specifications, and removal.

Multiple file systems within a single system

[edit]Frequently, retail systems are configured with a single file system occupying the entire storage device.

Another approach is to partition the disk so that several file systems with different attributes can be used. One file system, for use as browser cache or email storage, might be configured with a small allocation size. This keeps the activity of creating and deleting files typical of browser activity in a narrow area of the disk where it will not interfere with other file allocations. Another partition might be created for the storage of audio or video files with a relatively large block size. Yet another may normally be set read-only and only periodically be set writable. Some file systems, such as ZFS and APFS, support multiple file systems sharing a common pool of free blocks, supporting several file systems with different attributes without having to reserved a fixed amount of space for each file system.[14][15]

A third approach, which is mostly used in cloud systems, is to use "disk images" to house additional file systems, with the same attributes or not, within another (host) file system as a file. A common example is virtualization: one user can run an experimental Linux distribution (using the ext4 file system) in a virtual machine under their production Windows environment (using NTFS). The ext4 file system resides in a disk image, which is treated as a file (or multiple files, depending on the hypervisor and settings) in the NTFS host file system.

Having multiple file systems on a single system has the additional benefit that in the event of a corruption of a single file system, the remaining file systems will frequently still be intact. This includes virus destruction of the system file system or even a system that will not boot. File system utilities which require dedicated access can be effectively completed piecemeal. In addition, defragmentation may be more effective. Several system maintenance utilities, such as virus scans and backups, can also be processed in segments. For example, it is not necessary to backup the file system containing videos along with all the other files if none have been added since the last backup. As for the image files, one can easily "spin off" differential images which contain only "new" data written to the master (original) image. Differential images can be used for both safety concerns (as a "disposable" system - can be quickly restored if destroyed or contaminated by a virus, as the old image can be removed and a new image can be created in matter of seconds, even without automated procedures) and quick virtual machine deployment (since the differential images can be quickly spawned using a script in batches).

Types

[edit]Disk file systems

[edit]A disk file system takes advantages of the ability of disk storage media to randomly address data in a short amount of time. Additional considerations include the speed of accessing data following that initially requested and the anticipation that the following data may also be requested. This permits multiple users (or processes) access to various data on the disk without regard to the sequential location of the data. Examples include FAT (FAT12, FAT16, FAT32), exFAT, NTFS, ReFS, HFS and HFS+, HPFS, APFS, UFS, ext2, ext3, ext4, XFS, btrfs, Files-11, Veritas File System, VMFS, ZFS, ReiserFS, NSS and ScoutFS. Some disk file systems are journaling file systems or versioning file systems.

Optical discs

[edit]ISO 9660 and Universal Disk Format (UDF) are two common formats that target Compact Discs, DVDs and Blu-ray discs. Mount Rainier is an extension to UDF supported since 2.6 series of the Linux kernel and since Windows Vista that facilitates rewriting to DVDs.

Flash file systems

[edit]A flash file system considers the special abilities, performance and restrictions of flash memory devices. Frequently a disk file system can use a flash memory device as the underlying storage media, but it is much better to use a file system specifically designed for a flash device.[16]

Tape file systems

[edit]A tape file system is a file system and tape format designed to store files on tape. Magnetic tapes are sequential storage media with significantly longer random data access times than disks, posing challenges to the creation and efficient management of a general-purpose file system.

In a disk file system there is typically a master file directory, and a map of used and free data regions. Any file additions, changes, or removals require updating the directory and the used/free maps. Random access to data regions is measured in milliseconds so this system works well for disks.

Tape requires linear motion to wind and unwind potentially very long reels of media. This tape motion may take several seconds to several minutes to move the read/write head from one end of the tape to the other.

Consequently, a master file directory and usage map can be extremely slow and inefficient with tape. Writing typically involves reading the block usage map to find free blocks for writing, updating the usage map and directory to add the data, and then advancing the tape to write the data in the correct spot. Each additional file write requires updating the map and directory and writing the data, which may take several seconds to occur for each file.

Tape file systems instead typically allow for the file directory to be spread across the tape intermixed with the data, referred to as streaming, so that time-consuming and repeated tape motions are not required to write new data.

However, a side effect of this design is that reading the file directory of a tape usually requires scanning the entire tape to read all the scattered directory entries. Most data archiving software that works with tape storage will store a local copy of the tape catalog on a disk file system, so that adding files to a tape can be done quickly without having to rescan the tape media. The local tape catalog copy is usually discarded if not used for a specified period of time, at which point the tape must be re-scanned if it is to be used in the future.

IBM has developed a file system for tape called the Linear Tape File System. The IBM implementation of this file system has been released as the open-source IBM Linear Tape File System — Single Drive Edition (LTFS-SDE) product. The Linear Tape File System uses a separate partition on the tape to record the index meta-data, thereby avoiding the problems associated with scattering directory entries across the entire tape.

Tape formatting

[edit]Writing data to a tape, erasing, or formatting a tape is often a significantly time-consuming process and can take several hours on large tapes.[a] With many data tape technologies it is not necessary to format the tape before over-writing new data to the tape. This is due to the inherently destructive nature of overwriting data on sequential media.

Because of the time it can take to format a tape, typically tapes are pre-formatted so that the tape user does not need to spend time preparing each new tape for use. All that is usually necessary is to write an identifying media label to the tape before use, and even this can be automatically written by software when a new tape is used for the first time.

Database file systems

[edit]Another concept for file management is the idea of a database-based file system. Instead of, or in addition to, hierarchical structured management, files are identified by their characteristics, like type of file, topic, author, or similar rich metadata.[17]

IBM DB2 for i [18] (formerly known as DB2/400 and DB2 for i5/OS) is a database file system as part of the object based IBM i[19] operating system (formerly known as OS/400 and i5/OS), incorporating a single level store and running on IBM Power Systems (formerly known as AS/400 and iSeries), designed by Frank G. Soltis IBM's former chief scientist for IBM i. Around 1978 to 1988 Frank G. Soltis and his team at IBM Rochester had successfully designed and applied technologies like the database file system where others like Microsoft later failed to accomplish.[20] These technologies are informally known as 'Fortress Rochester'[citation needed] and were in few basic aspects extended from early Mainframe technologies but in many ways more advanced from a technological perspective[citation needed].

Some other projects that are not "pure" database file systems but that use some aspects of a database file system:

- Many Web content management systems use a relational DBMS to store and retrieve files. For example, XHTML files are stored as XML or text fields, while image files are stored as blob fields; SQL SELECT (with optional XPath) statements retrieve the files, and allow the use of a sophisticated logic and more rich information associations than "usual file systems." Many CMSs also have the option of storing only metadata within the database, with the standard filesystem used to store the content of files.

- Very large file systems, embodied by applications like Apache Hadoop and Google File System, use some database file system concepts.

Transactional file systems

[edit]Some programs need to either make multiple file system changes, or, if one or more of the changes fail for any reason, make none of the changes. For example, a program which is installing or updating software may write executables, libraries, and/or configuration files. If some of the writing fails and the software is left partially installed or updated, the software may be broken or unusable. An incomplete update of a key system utility, such as the command shell, may leave the entire system in an unusable state.

Transaction processing introduces the atomicity guarantee, ensuring that operations inside of a transaction are either all committed or the transaction can be aborted and the system discards all of its partial results. This means that if there is a crash or power failure, after recovery, the stored state will be consistent. Either the software will be completely installed or the failed installation will be completely rolled back, but an unusable partial install will not be left on the system. Transactions also provide the isolation guarantee[clarification needed], meaning that operations within a transaction are hidden from other threads on the system until the transaction commits, and that interfering operations on the system will be properly serialized with the transaction.

Windows, beginning with Vista, added transaction support to NTFS, in a feature called Transactional NTFS, but its use is now discouraged.[21] There are a number of research prototypes of transactional file systems for UNIX systems, including the Valor file system,[22] Amino,[23] LFS,[24] and a transactional ext3 file system on the TxOS kernel,[25] as well as transactional file systems targeting embedded systems, such as TFFS.[26]

Ensuring consistency across multiple file system operations is difficult, if not impossible, without file system transactions. File locking can be used as a concurrency control mechanism for individual files, but it typically does not protect the directory structure or file metadata. For instance, file locking cannot prevent TOCTTOU race conditions on symbolic links. File locking also cannot automatically roll back a failed operation, such as a software upgrade; this requires atomicity.

Journaling file systems is one technique used to introduce transaction-level consistency to file system structures. Journal transactions are not exposed to programs as part of the OS API; they are only used internally to ensure consistency at the granularity of a single system call.

Data backup systems typically do not provide support for direct backup of data stored in a transactional manner, which makes the recovery of reliable and consistent data sets difficult. Most backup software simply notes what files have changed since a certain time, regardless of the transactional state shared across multiple files in the overall dataset. As a workaround, some database systems simply produce an archived state file containing all data up to that point, and the backup software only backs that up and does not interact directly with the active transactional databases at all. Recovery requires separate recreation of the database from the state file after the file has been restored by the backup software.

Network file systems

[edit]A network file system is a file system that acts as a client for a remote file access protocol, providing access to files on a server. Programs using local interfaces can transparently create, manage and access hierarchical directories and files in remote network-connected computers. Examples of network file systems include clients for the NFS,[27] AFS, SMB protocols, and file-system-like clients for FTP and WebDAV.

Shared disk file systems

[edit]A shared disk file system is one in which a number of machines (usually servers) all have access to the same external disk subsystem (usually a storage area network). The file system arbitrates access to that subsystem, preventing write collisions.[28] Examples include GFS2 from Red Hat, GPFS, now known as Spectrum Scale, from IBM, SFS from DataPlow, CXFS from SGI, StorNext from Quantum Corporation and ScoutFS from Versity.

Special file systems

[edit]

Some file systems expose elements of the operating system as files so they can be acted on via the file system API. This is common in Unix-like operating systems, and to a lesser extent in other operating systems. Examples include:

- devfs, udev, TOPS-10 expose I/O devices or pseudo-devices as special files

- configfs and sysfs expose special files that can be used to query and configure Linux kernel information

- procfs exposes process information as special files

Minimal file system / audio-cassette storage

[edit]In the 1970s disk and digital tape devices were too expensive for some early microcomputer users. An inexpensive basic data storage system was devised that used common audio cassette tape.

When the system needed to write data, the user was notified to press "RECORD" on the cassette recorder, then press "RETURN" on the keyboard to notify the system that the cassette recorder was recording. The system wrote a sound to provide time synchronization, then modulated sounds that encoded a prefix, the data, a checksum and a suffix. When the system needed to read data, the user was instructed to press "PLAY" on the cassette recorder. The system would listen to the sounds on the tape waiting until a burst of sound could be recognized as the synchronization. The system would then interpret subsequent sounds as data. When the data read was complete, the system would notify the user to press "STOP" on the cassette recorder. It was primitive, but it (mostly) worked. Data was stored sequentially, usually in an unnamed format, although some systems (such as the Commodore PET series of computers) did allow the files to be named. Multiple sets of data could be written and located by fast-forwarding the tape and observing at the tape counter to find the approximate start of the next data region on the tape. The user might have to listen to the sounds to find the right spot to begin playing the next data region. Some implementations even included audible sounds interspersed with the data.

Flat file systems

[edit]In a flat file system, there are no subdirectories; directory entries for all files are stored in a single directory.

When floppy disk media was first available this type of file system was adequate due to the relatively small amount of data space available. CP/M machines featured a flat file system, where files could be assigned to one of 16 user areas and generic file operations narrowed to work on one instead of defaulting to work on all of them. These user areas were no more than special attributes associated with the files; that is, it was not necessary to define specific quota for each of these areas and files could be added to groups for as long as there was still free storage space on the disk. The early Apple Macintosh also featured a flat file system, the Macintosh File System. It was unusual in that the file management program (Macintosh Finder) created the illusion of a partially hierarchical filing system on top of EMFS. This structure required every file to have a unique name, even if it appeared to be in a separate folder. IBM DOS/360 and OS/360 store entries for all files on a disk pack (volume) in a directory on the pack called a Volume Table of Contents (VTOC).

While simple, flat file systems become awkward as the number of files grows and makes it difficult to organize data into related groups of files.

A recent addition to the flat file system family is Amazon's S3, a remote storage service, which is intentionally simplistic to allow users the ability to customize how their data is stored. The only constructs are buckets (imagine a disk drive of unlimited size) and objects (similar, but not identical to the standard concept of a file). Advanced file management is allowed by being able to use nearly any character (including '/') in the object's name, and the ability to select subsets of the bucket's content based on identical prefixes.

Implementations

[edit]An operating system (OS) typically supports one or more file systems. Sometimes an OS and its file system are so tightly interwoven that it is difficult to describe them independently.

An OS typically provides file system access to the user. Often an OS provides command line interface, such as Unix shell, Windows Command Prompt and PowerShell, and OpenVMS DCL. An OS often also provides graphical user interface file browsers such as MacOS Finder and Windows File Explorer.

Unix and Unix-like operating systems

[edit]Unix-like operating systems create a virtual file system, which makes all the files on all the devices appear to exist in a single hierarchy. This means, in those systems, there is one root directory, and every file existing on the system is located under it somewhere. Unix-like systems can use a RAM disk or network shared resource as its root directory.

Unix-like systems assign a device name to each device, but this is not how the files on that device are accessed. Instead, to gain access to files on another device, the operating system must first be informed where in the directory tree those files should appear. This process is called mounting a file system. For example, to access the files on a CD-ROM, one must tell the operating system "Take the file system from this CD-ROM and make it appear under such-and-such directory." The directory given to the operating system is called the mount point – it might, for example, be /media. The /media directory exists on many Unix systems (as specified in the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard) and is intended specifically for use as a mount point for removable media such as CDs, DVDs, USB drives or floppy disks. It may be empty, or it may contain subdirectories for mounting individual devices. Generally, only the administrator (i.e. root user) may authorize the mounting of file systems.

Unix-like operating systems often include software and tools that assist in the mounting process and provide it new functionality. Some of these strategies have been coined "auto-mounting" as a reflection of their purpose.

- In many situations, file systems other than the root need to be available as soon as the operating system has booted. All Unix-like systems therefore provide a facility for mounting file systems at boot time. System administrators define these file systems in the configuration file fstab (vfstab in Solaris), which also indicates options and mount points.

- In some situations, there is no need to mount certain file systems at boot time, although their use may be desired thereafter. There are some utilities for Unix-like systems that allow the mounting of predefined file systems upon demand.

- Removable media allow programs and data to be transferred between machines without a physical connection. Common examples include USB flash drives, CD-ROMs, and DVDs. Utilities have therefore been developed to detect the presence and availability of a medium and then mount that medium without any user intervention.

- Progressive Unix-like systems have also introduced a concept called supermounting; see, for example, the Linux supermount-ng project. For example, a floppy disk that has been supermounted can be physically removed from the system. Under normal circumstances, the disk should have been synchronized and then unmounted before its removal. Provided synchronization has occurred, a different disk can be inserted into the drive. The system automatically notices that the disk has changed and updates the mount point contents to reflect the new medium.

- An automounter will automatically mount a file system when a reference is made to the directory atop which it should be mounted. This is usually used for file systems on network servers, rather than relying on events such as the insertion of media, as would be appropriate for removable media.

Linux

[edit]Linux supports numerous file systems, but common choices for the system disk on a block device include the ext* family (ext2, ext3 and ext4), XFS, JFS, and btrfs. For raw flash without a flash translation layer (FTL) or Memory Technology Device (MTD), there are UBIFS, JFFS2 and YAFFS, among others. SquashFS is a common compressed read-only file system.

Solaris

[edit]Solaris in earlier releases defaulted to (non-journaled or non-logging) UFS for bootable and supplementary file systems. Solaris defaulted to, supported, and extended UFS.

Support for other file systems and significant enhancements were added over time, including Veritas Software Corp. (journaling) VxFS, Sun Microsystems (clustering) QFS, Sun Microsystems (journaling) UFS, and Sun Microsystems (open source, poolable, 128 bit compressible, and error-correcting) ZFS.

Kernel extensions were added to Solaris to allow for bootable Veritas VxFS operation. Logging or journaling was added to UFS in Sun's Solaris 7. Releases of Solaris 10, Solaris Express, OpenSolaris, and other open source variants of the Solaris operating system later supported bootable ZFS.

Logical Volume Management allows for spanning a file system across multiple devices for the purpose of adding redundancy, capacity, and/or throughput. Legacy environments in Solaris may use Solaris Volume Manager (formerly known as Solstice DiskSuite). Multiple operating systems (including Solaris) may use Veritas Volume Manager. Modern Solaris based operating systems eclipse the need for volume management through leveraging virtual storage pools in ZFS.

macOS

[edit]macOS (formerly Mac OS X) uses the Apple File System (APFS), which in 2017 replaced a file system inherited from classic Mac OS called HFS Plus (HFS+). Apple also uses the term "Mac OS Extended" for HFS+.[29] HFS Plus is a metadata-rich and case-preserving but (usually) case-insensitive file system. Due to the Unix roots of macOS, Unix permissions were added to HFS Plus. Later versions of HFS Plus added journaling to prevent corruption of the file system structure and introduced a number of optimizations to the allocation algorithms in an attempt to defragment files automatically without requiring an external defragmenter.

File names can be up to 255 characters. HFS Plus uses Unicode to store file names. On macOS, the filetype can come from the type code, stored in file's metadata, or the filename extension.

HFS Plus has three kinds of links: Unix-style hard links, Unix-style symbolic links, and aliases. Aliases are designed to maintain a link to their original file even if they are moved or renamed; they are not interpreted by the file system itself, but by the File Manager code in userland.

macOS 10.13 High Sierra, which was announced on June 5, 2017, at Apple's WWDC event, uses the Apple File System on solid-state drives.

macOS also supported the UFS file system, derived from the BSD Unix Fast File System via NeXTSTEP. However, as of Mac OS X Leopard, macOS could no longer be installed on a UFS volume, nor can a pre-Leopard system installed on a UFS volume be upgraded to Leopard.[30] As of Mac OS X Lion UFS support was completely dropped.

Newer versions of macOS are capable of reading and writing to the legacy FAT file systems (16 and 32) common on Windows. They are also capable of reading the newer NTFS file systems for Windows. In order to write to NTFS file systems on macOS versions prior to Mac OS X Snow Leopard third-party software is necessary. Mac OS X 10.6 (Snow Leopard) and later allow writing to NTFS file systems, but only after a non-trivial system setting change (third-party software exists that automates this).[31]

Finally, macOS supports reading and writing of the exFAT file system since Mac OS X Snow Leopard, starting from version 10.6.5.[32]

OS/2

[edit]OS/2 1.2 introduced the High Performance File System (HPFS). HPFS supports mixed case file names in different code pages, long file names (255 characters), more efficient use of disk space, an architecture that keeps related items close to each other on the disk volume, less fragmentation of data, extent-based space allocation, a B+ tree structure for directories, and the root directory located at the midpoint of the disk, for faster average access. A journaled filesystem (JFS) was shipped in 1999.

PC-BSD

[edit]PC-BSD is a desktop version of FreeBSD, which inherits FreeBSD's ZFS support, similarly to FreeNAS. The new graphical installer of PC-BSD can handle / (root) on ZFS and RAID-Z pool installs and disk encryption using Geli right from the start in an easy convenient (GUI) way. The current PC-BSD 9.0+ 'Isotope Edition' has ZFS filesystem version 5 and ZFS storage pool version 28.

Plan 9

[edit]Plan 9 from Bell Labs treats everything as a file and accesses all objects as a file would be accessed (i.e., there is no ioctl or mmap): networking, graphics, debugging, authentication, capabilities, encryption, and other services are accessed via I/O operations on file descriptors. The 9P protocol removes the difference between local and remote files. File systems in Plan 9 are organized with the help of private, per-process namespaces, allowing each process to have a different view of the many file systems that provide resources in a distributed system.

The Inferno operating system shares these concepts with Plan 9.

Microsoft Windows

[edit]

Windows makes use of the FAT, NTFS, exFAT, Live File System and ReFS file systems (the last of these is only supported and usable in Windows Server 2012, Windows Server 2016, Windows 8, Windows 8.1, and Windows 10; Windows cannot boot from it).

Windows uses a drive letter abstraction at the user level to distinguish one disk or partition from another. For example, the path C:\WINDOWS represents a directory WINDOWS on the partition represented by the letter C. Drive C: is most commonly used for the primary hard disk drive partition, on which Windows is usually installed and from which it boots. This "tradition" has become so firmly ingrained that bugs exist in many applications which make assumptions that the drive that the operating system is installed on is C. The use of drive letters, and the tradition of using "C" as the drive letter for the primary hard disk drive partition, can be traced to MS-DOS, where the letters A and B were reserved for up to two floppy disk drives. This in turn derived from CP/M in the 1970s, and ultimately from IBM's CP/CMS of 1967.

FAT

[edit]The family of FAT file systems is supported by almost all operating systems for personal computers, including all versions of Windows and MS-DOS/PC DOS, OS/2, and DR-DOS. (PC DOS is an OEM version of MS-DOS, MS-DOS was originally based on SCP's 86-DOS. DR-DOS was based on Digital Research's Concurrent DOS, a successor of CP/M-86.) The FAT file systems are therefore well-suited as a universal exchange format between computers and devices of most any type and age.

The FAT file system traces its roots back to an (incompatible) 8-bit FAT precursor in Standalone Disk BASIC and the short-lived MDOS/MIDAS project.[citation needed]

Over the years, the file system has been expanded from FAT12 to FAT16 and FAT32. Various features have been added to the file system including subdirectories, codepage support, extended attributes, and long filenames. Third parties such as Digital Research have incorporated optional support for deletion tracking, and volume/directory/file-based multi-user security schemes to support file and directory passwords and permissions such as read/write/execute/delete access rights. Most of these extensions are not supported by Windows.

The FAT12 and FAT16 file systems had a limit on the number of entries in the root directory of the file system and had restrictions on the maximum size of FAT-formatted disks or partitions.

FAT32 addresses the limitations in FAT12 and FAT16, except for the file size limit of close to 4 GB, but it remains limited compared to NTFS.

FAT12, FAT16 and FAT32 also have a limit of eight characters for the file name, and three characters for the extension (such as .exe). This is commonly referred to as the 8.3 filename limit. VFAT, an optional extension to FAT12, FAT16 and FAT32, introduced in Windows 95 and Windows NT 3.5, allowed long file names (LFN) to be stored in the FAT file system in a backwards compatible fashion.

NTFS

[edit]NTFS, introduced with the Windows NT operating system in 1993, allowed ACL-based permission control. Other features also supported by NTFS include hard links, multiple file streams, attribute indexing, quota tracking, sparse files, encryption, compression, and reparse points (directories working as mount-points for other file systems, symlinks, junctions, remote storage links).

exFAT

[edit]exFAT has certain advantages over NTFS with regard to file system overhead.[citation needed]

exFAT is not backward compatible with FAT file systems such as FAT12, FAT16 or FAT32. The file system is supported with newer Windows systems, such as Windows XP, Windows Server 2003, Windows Vista, Windows 2008, Windows 7, Windows 8, Windows 8.1, Windows 10 and Windows 11.

exFAT is supported in macOS starting with version 10.6.5 (Snow Leopard).[32] Support in other operating systems is sparse since implementing support for exFAT requires a license. exFAT is the only file system that is fully supported on both macOS and Windows that can hold files larger than 4 GB.[33][34]

OpenVMS

[edit]MVS

[edit]Prior to the introduction of VSAM, OS/360 systems implemented a hybrid file system. The system was designed to easily support removable disk packs, so the information relating to all files on one disk (volume in IBM terminology) is stored on that disk in a flat system file called the Volume Table of Contents (VTOC). The VTOC stores all metadata for the file. Later a hierarchical directory structure was imposed with the introduction of the System Catalog, which can optionally catalog files (datasets) on resident and removable volumes. The catalog only contains information to relate a dataset to a specific volume. If the user requests access to a dataset on an offline volume, and they have suitable privileges, the system will attempt to mount the required volume. Cataloged and non-cataloged datasets can still be accessed using information in the VTOC, bypassing the catalog, if the required volume id is provided to the OPEN request. Still later the VTOC was indexed to speed up access.

Conversational Monitor System

[edit]The IBM Conversational Monitor System (CMS) component of VM/370 uses a separate flat file system for each virtual disk (minidisk). File data and control information are scattered and intermixed. The anchor is a record called the Master File Directory (MFD), always located in the fourth block on the disk. Originally CMS used fixed-length 800-byte blocks, but later versions used larger size blocks up to 4K. Access to a data record requires two levels of indirection, where the file's directory entry (called a File Status Table (FST) entry) points to blocks containing a list of addresses of the individual records.

AS/400 file system

[edit]Data on the AS/400 and its successors consists of system objects mapped into the system virtual address space in a single-level store. Many types of objects are defined including the directories and files found in other file systems. File objects, along with other types of objects, form the basis of the AS/400's support for an integrated relational database.

Other file systems

[edit]- The Prospero File System is a file system based on the Virtual System Model.[35] The system was created by B. Clifford Neuman of the Information Sciences Institute at the University of Southern California.

- RSRE FLEX file system - written in ALGOL 68

- The file system of the Michigan Terminal System (MTS) is interesting because: (i) it provides "line files" where record lengths and line numbers are associated as metadata with each record in the file, lines can be added, replaced, updated with the same or different length records, and deleted anywhere in the file without the need to read and rewrite the entire file; (ii) using program keys files may be shared or permitted to commands and programs in addition to users and groups; and (iii) there is a comprehensive file locking mechanism that protects both the file's data and its metadata.[36][37]

- TempleOS uses RedSea, a file system made by Terry A. Davis.[38]

Limitations

[edit]Design limitations

[edit]File systems limit storable data capacity – generally driven by the typical size of storage devices at the time the file system is designed and anticipated into the foreseeable future.

Since storage sizes have increased at near exponential rate (see Moore's law), newer storage devices often exceed existing file system limits within only a few years after introduction. This requires new file systems with ever increasing capacity.

With higher capacity, the need for capabilities and therefore complexity increases as well. File system complexity typically varies proportionally with available storage capacity. Capacity issues aside, the file systems of early 1980s home computers with 50 KB to 512 KB of storage would not be a reasonable choice for modern storage systems with hundreds of gigabytes of capacity. Likewise, modern file systems would not be a reasonable choice for these early systems, since the complexity of modern file system structures would quickly consume the limited capacity of early storage systems.

Converting the type of a file system

[edit]It may be advantageous or necessary to have files in a different file system than they currently exist. Reasons include the need for an increase in the space requirements beyond the limits of the current file system. The depth of path may need to be increased beyond the restrictions of the file system. There may be performance or reliability considerations. Providing access to another operating system which does not support the existing file system is another reason.

In-place conversion

[edit]In some cases conversion can be done in-place, although migrating the file system is more conservative, as it involves a creating a copy of the data and is recommended.[39] On Windows, FAT and FAT32 file systems can be converted to NTFS via the convert.exe utility, but not the reverse.[39] On Linux, ext2 can be converted to ext3 (and converted back), and ext3 can be converted to ext4 (but not back),[40] and both ext3 and ext4 can be converted to btrfs, and converted back until the undo information is deleted.[41] These conversions are possible due to using the same format for the file data itself, and relocating the metadata into empty space, in some cases using sparse file support.[41]

Migrating to a different file system

[edit]Migration has the disadvantage of requiring additional space although it may be faster. The best case is if there is unused space on media which will contain the final file system.

For example, to migrate a FAT32 file system to an ext2 file system, a new ext2 file system is created. Then the data from the FAT32 file system is copied to the ext2 one, and the old file system is deleted.

An alternative, when there is not sufficient space to retain the original file system until the new one is created, is to use a work area (such as a removable media). This takes longer but has the benefit of producing a backup.

Long file paths and long file names

[edit]In hierarchical file systems, files are accessed by means of a path that is a branching list of directories containing the file. Different file systems have different limits on the depth of the path. File systems also have a limit on the length of an individual file name.

Copying files with long names or located in paths of significant depth from one file system to another may cause undesirable results. This depends on how the utility doing the copying handles the discrepancy.

See also

[edit]- Comparison of file systems

- Computer data storage

- Disk quota

- List of file systems

- List of Unix commands

- Directory structure

- Shared resource

- Distributed file system

- Distributed Data Management Architecture

- File manager

- File system fragmentation

- Filename extension

- Global file system

- Object storage

- Storage efficiency

- Synthetic file system

- Virtual file system

Notes

[edit]- ^ An LTO-6 2.5 TB tape requires more than 4 hours to write at 160 MB/Sec

References

[edit]- ^ "5.10. Filesystems". The Linux Document Project. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

A filesystem is the methods and data structures that an operating system uses to keep track of files on a disk or partition; that is, the way the files are organized on the disk.

- ^ Arpaci-Dusseau, Remzi H.; Arpaci-Dusseau, Andrea C. (2014), File System Implementation (PDF), Arpaci-Dusseau Books

- ^ "Storage, IT Technology and Markets, Status and Evolution" (PDF). September 20, 2018.

HDD still key storage for the foreseeable future, SSDs not cost effective for capacity

- ^ McGill, Florence E. (1922). Office Practice and Business Procedure. Gregg Publishing Company. p. 197. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ Waring, R.L. (1961). Technical investigations of addition of a hardcopy output to the elements of a mechanized library system : final report, 20 Sept. 1961. Cincinnati, OH: Svco Corporation. OCLC 310795767.

- ^ Disc File Applications: Reports Presented at the Nation's First Disc File Symposium. American Data Processing. 1964. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c Amir, Yair. "Operating Systems 600.418 The File System". Department of Computer Science Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ a b IBM Corporation. "Component Structure of the Logical File System". IBM Knowledge Center. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ R. C. Daley; P. G. Neumann (1965). "A General-Purpose File System For Secondary Storage". Proceedings of the November 30--December 1, 1965, fall joint computer conference, Part I on XX - AFIPS '65 (Fall, part I). Fall Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS. pp. 213–229. doi:10.1145/1463891.1463915. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- ^ Carrier 2005, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Valvano, Jonathan W. (2011). Embedded Microcomputer Systems: Real Time Interfacing (Third ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 524. ISBN 978-1-111-42625-5. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "KSAM: A B + -tree-based keyed sequential-access method". ResearchGate. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Mohan, I. Chandra (2013). Operating Systems. Delhi: PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 166. ISBN 9788120347267. Retrieved 2014-07-27.

The word dentry is short for 'directory entry'. A dentry is nothing but a specific component in the path from the root. They (directory name or file name) provide for accessing files or directories[.]

- ^ "Chapter 22. The Z File System (ZFS)". The FreeBSD Handbook.

Pooled storage: adding physical storage devices to a pool, and allocating storage space from that shared pool. Space is available to all file systems and volumes, and increases by adding new storage devices to the pool.

- ^ "About Apple File System (APFS)". DaisyDisk User Guide.

APFS introduces space sharing between volumes. In APFS, every physical disk is a container that can have multiple volumes inside, which share the same pool of free space.

- ^ Douglis, Fred; Cáceres, Ramón; Kaashoek, M. Frans; Krishnan, P.; Li, Kai; Marsh, Brian; Tauber, Joshua (1994). "18. Storage Alternatives for Mobile Computers". Mobile Computing. Vol. 353. USENIX. pp. 473–505. doi:10.1007/978-0-585-29603-6_18. ISBN 978-0-585-29603-6. S2CID 2441760.

- ^ "Windows on a database – sliced and diced by BeOS vets". theregister.co.uk. 2002-03-29. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ "IBM DB2 for i: Overview". 03.ibm.com. Archived from the original on 2013-08-02. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ "IBM developerWorks : New to IBM i". Ibm.com. 2011-03-08. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ "XP successor Longhorn goes SQL, P2P – Microsoft leaks". theregister.co.uk. 2002-01-28. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ "Alternatives to using Transactional NTFS (Windows)". Msdn.microsoft.com. 2013-12-05. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ Spillane, Richard; Gaikwad, Sachin; Chinni, Manjunath; Zadok, Erez; Wright, Charles P. (2009). Enabling transactional file access via lightweight kernel extensions (PDF). Seventh USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 2009).

- ^ Wright, Charles P.; Spillane, Richard; Sivathanu, Gopalan; Zadok, Erez (2007). "Extending ACID Semantics to the File System" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Storage. 3 (2): 4. doi:10.1145/1242520.1242521. S2CID 8939577.

- ^ Seltzer, Margo I. (1993). "Transaction Support in a Log-Structured File System" (PDF). Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Data Engineering.

- ^ Porter, Donald E.; Hofmann, Owen S.; Rossbach, Christopher J.; Benn, Alexander; Witchel, Emmett (October 2009). "Operating System Transactions" (PDF). Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP '09). Big Sky, MT.

- ^ Gal, Eran; Toledo, Sivan. A Transactional Flash File System for Microcontrollers (PDF). USENIX 2005.

- ^ Arpaci-Dusseau, Remzi H.; Arpaci-Dusseau, Andrea C. (2014), Sun's Network File System (PDF), Arpaci-Dusseau Books

- ^ Troppens, Ulf; Erkens, Rainer; Müller, Wolfgang (2004). Storage Networks Explained: Basics and Application of Fibre Channel SAN, NAS, iSCSI and InfiniBand. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 124–125. ISBN 0-470-86182-7. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Mac OS X: About file system journaling". Apple. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard: Installing on a UFS-formatted volume". apple.com. 19 October 2007. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ OSXDaily (2013-10-02). "How to Enable NTFS Write Support in Mac OS X". Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ a b Steve Bunting (2012-08-14). EnCase Computer Forensics - The Official EnCE: EnCase Certified Examiner. Wiley. ISBN 9781118219409. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ^ "File system formats available in Disk Utility on Mac". Apple Support.

- ^ "exFAT file system specification". Microsoft Docs.

- ^ The Prospero File System: A Global File System Based on the Virtual System Model. 1992.

- ^ Pirkola, G. C. (June 1975). "A file system for a general-purpose time-sharing environment". Proceedings of the IEEE. 63 (6): 918–924. doi:10.1109/PROC.1975.9856. ISSN 0018-9219. S2CID 12982770.

- ^ Pirkola, Gary C.; Sanguinetti, John. "The Protection of Information in a General Purpose Time-Sharing Environment". Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Trends and Applications 1977: Computer Security and Integrity. Vol. 10. pp. 106–114.

- ^ Davis, Terry A. (n.d.). "The Temple Operating System". www.templeos.org. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ a b "How to Convert FAT Disks to NTFS". Microsoft Docs.

- ^ "Ext4 Howto". kernel.org. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Conversion from Ext3". Btrfs wiki.

Sources

[edit]- de Boyne Pollard, Jonathan (1996). "Disc and volume size limits". Frequently Given Answers. Retrieved February 9, 2005.

- "OS/2 corrective service fix JR09427". IBM (FTP). Retrieved February 9, 2005.[dead ftp link] (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- "Attribute - $EA_INFORMATION (0xD0)". NTFS Information, Linux-NTFS Project. Retrieved February 9, 2005.

- "Attribute - $EA (0xE0)". NTFS Information, Linux-NTFS Project. Retrieved February 9, 2005.

- "Attribute - $STANDARD_INFORMATION (0x10)". NTFS Information, Linux-NTFS Project. Retrieved February 21, 2005.

- "Technical Note TN1150: HFS Plus Volume Format". Apple Inc. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- Brian Carrier (2005). File System Forensic Analysis. Addison Wesley.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Arpaci-Dusseau, Remzi H.; Arpaci-Dusseau, Andrea C. (2014). Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces. Arpaci-Dusseau Books.

- Carrier, Brian (2005). File System Forensic Analysis. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-26817-2.

- Custer, Helen (1994). Inside the Windows NT File System. Microsoft Press. ISBN 1-55615-660-X.

- Giampaolo, Dominic (1999). Practical File System Design with the Be File System (PDF). Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. ISBN 1-55860-497-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- McCoy, Kirby (1990). VMS File System Internals. VAX - VMS Series. Digital Press. ISBN 1-55558-056-4.

- Mitchell, Stan (1997). Inside the Windows 95 File System. O'Reilly. ISBN 1-56592-200-X.

- Nagar, Rajeev (1997). Windows NT File System Internals : A Developer's Guide. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-56592-249-5.

- Pate, Steve D. (2003). UNIX Filesystems: Evolution, Design, and Implementation. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-16483-6. Archived from the original on 2013-11-24. Retrieved 2010-10-17.

- Rosenblum, Mendel (1994). The Design and Implementation of a Log-Structured File System. The Springer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-9541-7.

- Russinovich, Mark; Solomon, David A.; Ionescu, Alex (2009). "File Systems". Windows Internals (5th ed.). Microsoft Press. ISBN 978-0-7356-2530-3.

- Prabhakaran, Vijayan (2006). IRON File Systems. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Silberschatz, Abraham; Galvin, Peter Baer; Gagne, Greg (2004). "Storage Management". Operating System Concepts (7th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-69466-5.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (2007). Modern operating Systems (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-600663-3.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Woodhull, Albert S. (2006). Operating Systems: Design and Implementation (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-142938-8.

Online

[edit]- Benchmarking Filesystems (outdated) by Justin Piszcz, Linux Gazette 102, May 2004

- Benchmarking Filesystems Part II using kernel 2.6, by Justin Piszcz, Linux Gazette 122, January 2006

- Filesystems (ext3, ReiserFS, XFS, JFS) comparison on Debian Etch Archived 2008-09-13 at the Wayback Machine 2006

- Interview With the People Behind JFS, ReiserFS & XFS

- Journal File System Performance (outdated): ReiserFS, JFS, and Ext3FS show their merits on a fast RAID appliance

- Journaled Filesystem Benchmarks (outdated): A comparison of ReiserFS, XFS, JFS, ext3 & ext2

- Large List of File System Summaries (most recent update 2006-11-19)

- Linux File System Benchmarks v2.6 kernel with a stress on CPU usage

- "Linux 2.6 Filesystem Benchmarks (Older)". Archived from the original on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- Linux large file support (outdated)

- Local Filesystems for Windows

- Overview of some filesystems (outdated)

- Sparse files support (outdated)

- Jeremy Reimer (March 16, 2008). "From BFS to ZFS: past, present, and future of file systems". arstechnica.com. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

External links

[edit]- "Filesystem Specifications - Links & Whitepapers". Archived from the original on 2015-11-03.

- Interesting File System Projects

File system

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

A file system is an abstraction layer in an operating system that organizes, stores, and retrieves data on persistent storage media such as hard drives or solid-state drives, treating files as named, logical collections of related data bytes.[10][11] This abstraction hides the complexities of physical storage, such as disk sectors and blocks, from applications and users, presenting data instead as structured entities that can be easily accessed and manipulated.[12] File systems are typically agnostic to the specific contents of files, allowing them to handle diverse data types without interpreting the information itself.[11] The primary purpose of a file system is to enable reliable, long-term persistence of data beyond program execution or system restarts, while supporting efficient organization and access for both users and applications.[13] It facilitates hierarchical structuring of files through directories, tracks essential metadata such as file size, creation timestamps, ownership, and permissions, and manages space allocation to prevent data corruption or loss.[14] By providing these features, file systems bridge low-level hardware operations—like reading or writing fixed-size blocks on a disk—with high-level software needs, such as sequential or random access to variable-length streams.[15] Key concepts in file systems distinguish between files, which serve as containers for raw data, and directories, which act as organizational units grouping files and subdirectories into navigable structures.[16] Metadata, stored separately from the file contents, includes attributes like identifiers, locations on storage, protection controls, and usage timestamps, enabling secure and trackable operations.[14] For instance, file systems abstract the linear arrangement of disk sectors into logical views, such as tree-like hierarchies for directories or linear streams for file contents, simplifying data management across diverse hardware.[17][12]Historical Development

The development of file systems began in the 1950s with early computing systems relying on punch cards and magnetic tapes for data storage. Punch cards served as a sequential medium for input and storage in machines like the IBM 701, introduced in 1952, but magnetic tape emerged as a key advancement. The IBM 726 tape drive, paired with the 701 in 1953, provided the first commercial magnetic tape storage for computers, capable of holding 2 million digits on a single reel at speeds of 70 inches per second. These systems treated files as sequential records without hierarchical organization, limiting access to linear reads and writes.[18][19] By the 1960s, the shift to disk-based storage marked a significant evolution, enabling random access and more efficient file management. IBM's OS/360, released in 1966 for the System/360 mainframe family, introduced direct access storage devices (DASD) like the IBM 2311 disk drive from 1964, which supported removable disk packs with capacities up to 7.25 MB. This allowed for the first widespread use of disk file systems in batch processing environments, organizing data into datasets accessible via indexed sequential methods, though still largely flat in structure.[20][21] The 1970s and 1980s brought innovations in hierarchical organization and user interfaces. The Unix file system, developed at Bell Labs in the early 1970s and first released in 1971, popularized a tree-like directory structure with nested subdirectories, inspired by Multics, enabling efficient file organization and permissions.[22] The File Allocation Table (FAT), created by Microsoft in 1977 for standalone Disk BASIC and adopted in MS-DOS by 1981, provided a simple bitmap-based allocation for floppy and hard disks, supporting basic directory hierarchies but limited by 8.3 filename constraints. Meanwhile, the Xerox Alto, unveiled in 1973, introduced graphical user interface (GUI) elements for file management through its Neptune file browser, allowing icon-based manipulation on a bitmapped display, influencing future personal computing designs.[23][24] In the 1990s and 2000s, file systems emphasized reliability through journaling and advanced features. Microsoft's NTFS, launched in 1993 with Windows NT 3.1, incorporated journaling to log metadata changes for crash recovery, alongside support for large volumes, encryption, and access control lists.[25] Linux's ext2, introduced in 1993 by Rémy Card and others, offered a robust inode-based structure succeeding the original ext, while ext3 in 2001 added journaling for faster recovery. Sun Microsystems' ZFS, announced in 2005, advanced data integrity with end-to-end checksums, copy-on-write mechanisms, and built-in volume management to detect and repair silent corruption.[26][27] The 2010s and 2020s saw adaptations for modern hardware, mobile devices, and distributed environments. Apple's APFS, released in 2017 with macOS High Sierra, optimized for SSDs with features like snapshots, cloning, and space sharing across volumes for enhanced performance on iOS and macOS devices. Btrfs, initiated by Chris Mason in 2007 and merged into the Linux kernel in 2009, introduced copy-on-write for snapshots and subvolumes, improving scalability and data integrity in Linux distributions. Distributed systems gained prominence with Ceph, originating from a 2006 OSDI paper and first released in 2007, providing scalable object storage with dynamic metadata distribution for cluster environments. Amazon S3, launched in 2006 as an object store, evolved in the 2020s with file system abstractions like S3 File Gateway and integrations for POSIX-like access, enabling cloud-native scalability for massive datasets in AI and big data applications.[28][29][30] Key innovations across this history include the transition from flat, sequential structures to hierarchical directories for better organization; the adoption of journaling in systems like NTFS, ext3, and ZFS to ensure crash recovery without full scans; and the integration of distributed and cloud paradigms in Ceph and S3 abstractions, addressing scalability for virtualization and AI workloads post-2020.[22][27][30]Architecture

Core Components

The architecture of many file systems, particularly block-based ones inspired by the Unix model such as ext4, includes core components that form the foundational structure for organizing and managing data on storage media. Variations exist in other file systems, such as NTFS or FAT, which use different structures like the Master File Table or File Allocation Table (detailed in the Types section). The superblock serves as the primary global metadata structure, containing essential parameters such as the total number of data blocks, block size, and file system state, which enable the operating system to interpret and access the file system layout.[31] In Unix-like systems, the superblock is typically located at a fixed offset on the device and includes counts of free blocks and inodes to facilitate space management.[32] The inode table consists of per-file metadata entries, each inode holding pointers to data blocks along with attributes like file size and ownership, allowing efficient mapping of logical file contents to physical storage locations.[31] Data blocks, in contrast, store the actual content of files, allocated in fixed-size units to balance performance and overhead on the underlying hardware.[31] These components interact through layered abstractions: device drivers provide low-level hardware access by handling I/O operations on physical devices like disks, while the file system driver translates logical block addresses to physical ones, ensuring data integrity during reads and writes.[33] In operating systems like Unix and Linux, the Virtual File System (VFS) layer acts as an abstraction interface, standardizing access to diverse file systems by intercepting system calls and routing them to the appropriate file system driver, thus enabling seamless integration of multiple file system types within a unified namespace.[34] Key processes underpin these interactions; mounting attaches the file system to the OS namespace by reading the superblock, validating the structure, and establishing the root directory in the global hierarchy, making its contents accessible to processes.[35] Unmounting reverses this by flushing pending writes, releasing resources, and detaching the file system to prevent data corruption during device removal or shutdown.[36] Formatting initializes the storage media by writing the superblock, allocating the inode table, and setting up initial data structures, preparing the device for use without existing data.[31] Supporting data structures include block allocation tables, often implemented as bitmaps to track free and allocated space across data blocks, enabling quick identification of available storage during file creation or extension.[32] Directory entries link human-readable file names to inode numbers, forming the basis for path resolution and navigation within the file system hierarchy.[37] Together, these elements ensure reliable data organization and access, with the superblock providing oversight, inodes and data blocks handling individual files, and abstraction layers bridging hardware and software.Metadata and File Attributes

In file systems, metadata refers to data that describes the properties and characteristics of files, distinct from the actual file content. This information enables the operating system to manage, access, and protect files efficiently. Metadata storage varies by file system type; for example, Unix-like systems store it separately from the file's data blocks in dedicated structures like inodes, while others like NTFS integrate it into file records within a central table.[38][39][40] Core file attributes form the foundational metadata and include essential details for file identification and operation. These encompass the file name (though often handled via directory entries), size in bytes, timestamps for creation (birth time, where supported), last modification (mtime), and last access (atime), as well as file type indicators such as regular files, directories, symbolic links, or special files like devices. Permissions are also core, specifying read, write, and execute access for the owner, group, and others, encoded in a mode field.[41][42][40] Extended attributes provide additional, flexible metadata beyond core properties, allowing for user-defined or system-specific information. Common examples include ownership details via user ID (UID) and group ID (GID), MIME types for content identification, and custom tags such as access control lists (ACLs) in modern systems like Linux. These are stored as name-value pairs and can be manipulated via system calls like setxattr.[43][42] Metadata storage often relies on fixed-size structures to ensure consistent access times and minimize fragmentation. In Unix-derived file systems, inodes serve as these structures, containing pointers to data blocks alongside attributes; for instance, the ext4 file system uses 256-byte inode records by default, with extra space allocated for extended attributes (up to 32 bytes for i_extra_isize as of Linux kernel 5.2). This design incurs overhead, as each file requires its own inode, potentially consuming significant space in directories with many small files—e.g., ext4's default allocates one inode per 16 KiB of filesystem space.[42][38]Organization and Storage

Directories and Hierarchies

In file systems, directories function as special files that serve as containers for organizing other files and subdirectories. Each directory maintains a list of entries, typically consisting of pairs that associate a file or subdirectory name with its corresponding inode—a data structure holding metadata such as permissions, timestamps, and pointers to data blocks. This design allows directories to act as navigational aids, enabling efficient lookup and access without storing the actual file contents. The root directory, often denoted by a forward slash (/), marks the apex of the hierarchy and contains initial subdirectories like those for system binaries or user home folders in Unix-like systems.[38][44] The hierarchical model structures directories and files into an inverted tree, where the root directory branches into parent-child relationships, with each subdirectory potentially spawning further levels. This organization promotes logical grouping, such as separating user data from system files, and supports scalability for managing vast numbers of items. Navigation within this tree relies on paths: absolute paths specify locations from the root (e.g., /home/user/documents), providing unambiguous references, while relative paths describe positions from the current working directory (e.g., ../docs), reducing redundancy in commands and scripts. This model originated in early Unix designs and remains foundational in modern operating systems for its balance of simplicity and extensibility.[45] Key operations on directories include creation via the mkdir system call, which allocates a new inode and initializes an empty entry list with specified permissions; deletion through rmdir, which removes an empty directory by freeing its inode only if no entries remain; and renaming with rename, which updates the name in the parent directory's entry table while preserving the inode. Traversal operations, essential for searching or listing contents, often employ depth-first search (DFS) to explore branches recursively—as in the find utility—or breadth-first search (BFS) for level-by-level scanning, as seen in tree-like listings from ls -R, optimizing for memory use in deep versus wide structures. These operations ensure atomicity where possible, preventing partial states during concurrent access.[46][47] Variations in hierarchy depth range from flat structures, where all files reside in a single directory without nesting, to deep hierarchies with multiple levels for fine-grained organization; flat models suit resource-constrained environments like embedded systems by minimizing overhead, but hierarchical ones excel in large-scale storage by easing management and reducing name collisions. To accommodate non-tree references, hard links create additional directory entries pointing to the same inode, allowing multiple paths to one file within the same file system, while symbolic links store a path string to another file or directory, enabling cross-file-system references but risking dangling links if the target moves. These mechanisms enhance flexibility without altering the core tree topology.[48][49]File Names and Paths