Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

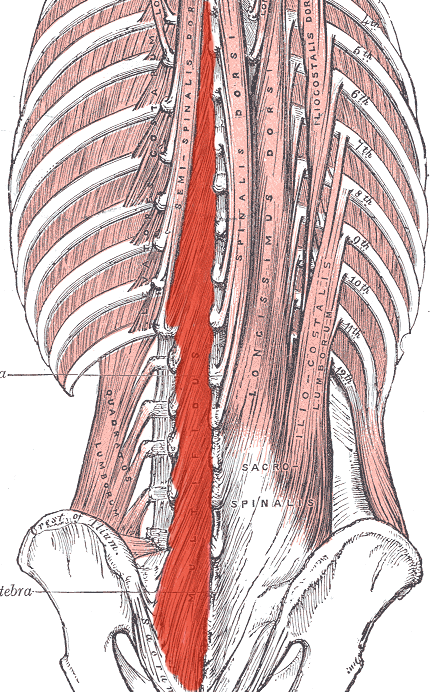

Multifidus muscle

View on Wikipedia| Multifidus muscle | |

|---|---|

Deep muscles of the back. (Multifidus shaded in red.) | |

Sacrum, dorsal surface. (Multifidus attachment outlined in red.) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Sacrum, erector spinae aponeurosis, PSIS, and iliac crest |

| Insertion | Spinous process |

| Nerve | Posterior branches |

| Actions | Provides proprioceptive feedback and input due to high muscle spindle density; Bilateral backward extension, unilateral ipsilateral side-bending and contralateral rotation. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus multifidus spinae |

| TA98 | A04.3.02.202 |

| TA2 | 2276 |

| FMA | 22827 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The multifidus (multifidus spinae; pl.: multifidi) muscle consists of a number of fleshy and tendinous fasciculi, which fill up the groove on either side of the spinous processes of the vertebrae, from the sacrum to the axis. While very thin, the multifidus muscle plays an important role in stabilizing the joints within the spine. The multifidus is one of the transversospinales.

Located just superficially to the spine itself, the multifidus muscle spans three joint segments and works to stabilize these joints at each level.

The stiffness and stability makes each vertebra work more effectively, and reduces the degeneration of the joint structures caused by friction from normal physical activity.

These fasciculi arise:

- in the sacral region: from the back of the sacrum, as low as the fourth sacral foramen, from the aponeurosis of origin of the sacrospinalis, from the medial surface of the posterior superior iliac spine, and from the posterior sacroiliac ligaments.

- in the lumbar region: from all the mamillary processes.

- in the thoracic region: from all the transverse processes.

- in the cervical region: from the articular processes of the lower four vertebrae.

Each fasciculus, passing obliquely upward and medially, is inserted into the whole length of the spinous process of one of the vertebræ above.

These fasciculi vary in length: the most superficial, the longest, pass from one vertebra to the third or fourth above; those next in order run from one vertebra to the second or third above; while the deepest connect two adjacent vertebrae.

The multifidus lies deep relative to the spinal erectors, transverse abdominis, abdominal internal oblique muscle and abdominal external oblique muscle.

Atrophy and association with low back pain

[edit]Dysfunction in the lumbar multifidus muscles is strongly associated with low back pain. The dysfunction can be caused by inhibition of pain by the spine. The dysfunction frequently persists even after the pain has disappeared. Such persistence may help explain the high recurrence rates of low back pain. Persistent lumbar multifidus dysfunction is diagnosed by atrophic replacement of the multifidus with fat, as visualized by magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound.[1][2] One way to help recruit and strengthen the lumbar multifidus muscles is by tensing the pelvic floor muscles for a few seconds "as if stopping urination midstream".[3]

Additional images

[edit]-

The posterior divisions of the sacral nerves

-

The multifidus muscles (labeled left) as seen in a posterior view of the neck

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 400 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 400 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Freeman, Michael D.; Woodham, Mark A.; Woodham, Andrew W. (2010-01-01). "The role of the lumbar multifidus in chronic low back pain: a review". PM&R. 2 (2): 142–6. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.11.006. PMID 20193941. S2CID 22246810.

- ^ Woodham, Mark; Woodham, Andrew; Skeate, Joseph G.; Freeman, Michael (May 2014). "Long-term lumbar multifidus muscle atrophy changes documented with magnetic resonance imaging: a case series". Journal of Radiology Case Reports. 8 (5): 27–34. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v8i5.1401. ISSN 1943-0922. PMC 4242062. PMID 25426227.

- ^ Chad Starkey, ed. (2012). "Additional Spine and Torso Therapeutic Exercises". Athletic Training and Sports Medicine: An Integrated Approach. Jones & Bartlett Publishers – American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-7637-9609-9.

External links

[edit]- Multifidus 1 at the Duke University Health System's Orthopedics program

- PTCentral

- Dissection at ithaca.edu