Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pelvis

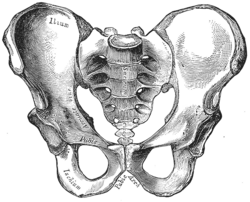

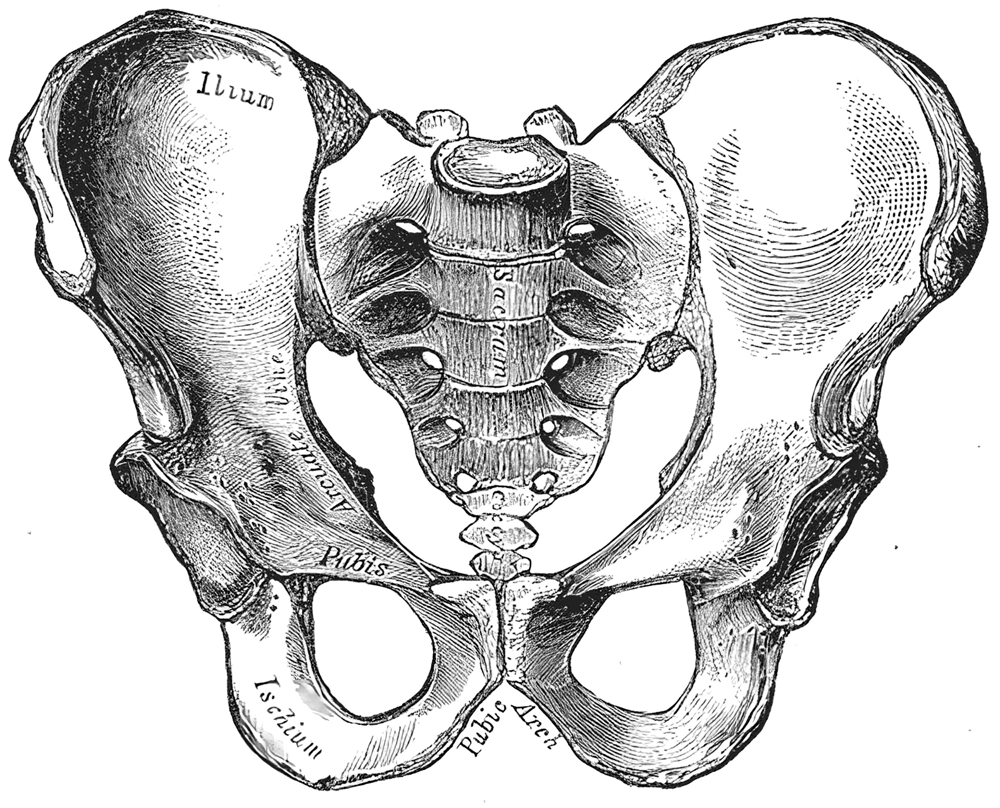

View on Wikipedia| Pelvis | |

|---|---|

Male type pelvis | |

Female type pelvis | |

| Details | |

| Nerve | Pelvic splanchnic nerves, superior hypogastric plexus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pelvis |

| MeSH | D010388 |

| TA98 | A02.5.02.001 |

| TA2 | 129 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The pelvis (pl.: pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of an anatomical trunk,[1] between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton[2] (sometimes also called bony pelvis or pelvic skeleton).

The pelvic region of the trunk includes the bony pelvis, the pelvic cavity (the space enclosed by the bony pelvis), the pelvic floor, below the pelvic cavity, and the perineum, below the pelvic floor.[1] The pelvic skeleton is formed in the area of the back, by the sacrum and the coccyx and anteriorly and to the left and right sides, by a pair of hip bones.

The two hip bones connect the spine with the lower limbs. They are attached to the sacrum posteriorly, connected to each other anteriorly, and joined with the two femurs at the hip joints. The gap enclosed by the bony pelvis, called the pelvic cavity, is the section of the body underneath the abdomen and mainly consists of the reproductive organs and the rectum, while the pelvic floor at the base of the cavity assists in supporting the organs of the abdomen.

In mammals, the bony pelvis has a gap in the middle, significantly larger in females than in males. Their offspring pass through this gap when they are born.

Structure

[edit]The pelvic region of the trunk is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs.[1] It includes several structures: the bony pelvis, the pelvic cavity, the pelvic floor, and the perineum. The bony pelvis (pelvic skeleton) is the part of the skeleton embedded in the pelvic region of the trunk. It is subdivided into the pelvic girdle and the pelvic spine. The pelvic girdle is composed of the appendicular hip bones (ilium, ischium, and pubis) oriented in a ring, and connects the pelvic region of the spine to the lower limbs. The pelvic spine consists of the sacrum and coccyx.[1]

- the pelvic cavity, typically defined as a small part of the space enclosed by the bony pelvis, delimited by the pelvic brim above and the pelvic floor below; alternatively, the pelvic cavity is sometimes also defined as the whole space enclosed by the pelvic skeleton, subdivided into:

- the greater (or false) pelvis, above the pelvic brim

- the lesser (or true) pelvis, below the pelvic brim

- the pelvic floor (or pelvic diaphragm), below the pelvic cavity

- the perineum, below the pelvic floor

Pelvic bone

[edit]

2–4. Hip bone (os coxae)

1. Sacrum (os sacrum), 2. Ilium (os ilium), 3. Ischium (os ischii)

4. Pubic bone (os pubis) (4a. corpus, 4b. ramus superior, 4c. ramus inferior, 4d. tuberculum pubicum)

5. Pubic symphysis, 6. Acetabulum (of the hip joint), 7. Obturator foramen, 8. Coccyx/tailbone (os coccygis)

Dotted. Linea terminalis of the pelvic brim.

The pelvic skeleton is formed posteriorly (in the area of the back), by the sacrum and the coccyx and laterally and anteriorly (forward and to the sides), by a pair of hip bones. Each hip bone consists of three sections: ilium, ischium, and pubis. During childhood, these sections are separate bones, joined by the triradiate cartilage. During puberty, they fuse together to form a single bone.

Pelvic cavity

[edit] |

|

|

The pelvic cavity is a body cavity that is bounded by the bones of the pelvis and which primarily contains reproductive organs and the rectum.

A distinction is made between the lesser or true pelvis inferior to the terminal line, and the greater or false pelvis above it. The pelvic inlet or superior pelvic aperture, which leads into the lesser pelvis, is bordered by the promontory, the arcuate line of ilium, the iliopubic eminence, the pecten of the pubis, and the upper part of the pubic symphysis. The pelvic outlet or inferior pelvic aperture is the region between the subpubic angle or pubic arch, the ischial tuberosities and the coccyx. [3]

- Ligaments: obturator membrane, inguinal ligament (lacunar ligament, iliopectineal arch)

Alternatively, the pelvis is divided into three planes: the inlet, midplane, and outlet.[4]

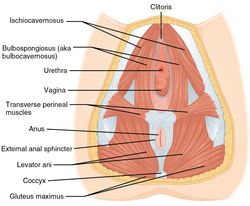

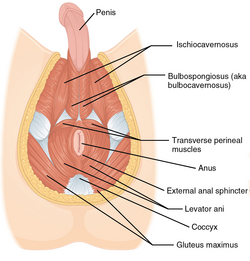

Pelvic floor

[edit]The pelvic floor has two inherently conflicting functions: One is to close the pelvic and abdominal cavities and bear the load of the visceral organs; the other is to control the openings of the rectum and urogenital organs that pierce the pelvic floor and make it weaker. To achieve both these tasks, the pelvic floor is composed of several overlapping sheets of muscles and connective tissues.[5]

The pelvic diaphragm is composed of the levator ani and the coccygeus muscle. These arise between the symphysis and the ischial spine and converge on the coccyx and the anococcygeal ligament which spans between the tip of the coccyx and the anal hiatus. This leaves a slit for the anal and urogenital openings. Because of the width of the genital aperture, which is wider in females, a second closing mechanism is required. The urogenital diaphragm consists mainly of the deep transverse perineal which arises from the inferior ischial and pubic rami and extends to the urogenital hiatus. The urogenital diaphragm is reinforced posteriorly by the superficial transverse perineal.[6]

The external anal and urethral sphincters close the anus and the urethra. The former is surrounded by the bulbospongiosus which narrows the vaginal introitus in females and surrounds the corpus spongiosum in males. Ischiocavernosus squeezes blood into the corpora cavernosa penis and clitoridis.[7]

Variation

[edit]Modern humans are to a large extent characterized by bipedal locomotion and large brains. Because the pelvis is vital to both locomotion and childbirth, natural selection has been confronted by two conflicting demands: a wide birth canal and locomotion efficiency, a conflict referred to as the "obstetrical dilemma". The female pelvis, or gynecoid pelvis,[8] has evolved to its maximum width for childbirth—a wider pelvis would make human females unable to walk. In contrast, human male pelvises are not constrained by the need to give birth and therefore are more optimized for bipedal locomotion.[9]

The principal differences between male and female true and false pelvis include:

- The female pelvis is larger and broader than the male pelvis which is taller, narrower, and more compact.[10] The female pelvis is lighter and thinner than the male pelvis.[11]

- The female inlet is larger and oval in shape, while the male sacral promontory projects further (i.e. the male inlet is more heart-shaped).[10]

- The sides of the male pelvis converge from the inlet to the outlet, whereas the sides of the female pelvis are wider apart.[12]

- The angle between the inferior pubic rami is acute (70 degrees) in males, but obtuse (90–100 degrees) in females. Accordingly, the angle is called subpubic angle in males and pubic arch in females.[10] Additionally, the bones forming the angle/arch are more concave in females but straight in males.[13]

- The distance between the ischia bones is small in males, making the outlet narrow, but large in females, who have a relatively large outlet. The ischial spines and tuberosities are heavier and project farther into the pelvic cavity in males. The greater sciatic notch is wider in females.[13]

- The iliac crests are higher and more pronounced in males, making the male false pelvis deeper and more narrow than in females.[13]

- The male sacrum is long, narrow, more straight, and has a pronounced sacral promontory. The female sacrum is shorter, wider, more curved posteriorly, and has a less pronounced promontory.[13]

- The acetabula are wider apart in females than in males.[13] In males, the acetabulum faces more laterally, while it faces more anteriorly in females. Consequently, when males walk the leg can move forwards and backwards in a single plane. In females, the leg must swing forward and inward, from where the pivoting head of the femur moves the leg back in another plane. This change in the angle of the femoral head gives the female gait its characteristic (i.e. swinging of hips).[14]

Development

[edit]Each side of the pelvis is formed as cartilage, which ossifies as three main bones which stay separate through childhood: ilium, ischium, pubis. At birth the whole of the hip joint (the acetabulum area and the top of the femur) is still made of cartilage (but there may be a small piece of bone in the great trochanter of the femur); this makes it difficult to detect congenital hip dislocation by X-raying.

"In terms of comparative anatomy the human scapula represents two bones that have become fused together; the (dorsal) scapula proper and the (ventral) coracoid. The epiphyseal line across the glenoid cavity is the line of fusion. They are the counterparts of the ilium and ischium of the pelvic girdle."

— R. J. Last – Last's Anatomy

There is preliminary evidence that the pelvis continues to widen over the course of a lifetime.[15][16]

Functions

[edit]The skeleton of the pelvis is a basin-shaped ring of bones connecting the vertebral column to the femora. It is then connected to two hip bones.

Its primary functions are to bear the weight of the upper body when sitting and standing, transferring that weight from the axial skeleton to the lower appendicular skeleton when standing and walking, and providing attachments for and withstanding the forces of the powerful muscles of locomotion and posture. Compared to the shoulder girdle, the pelvic girdle is thus strong and rigid.[1]

Its secondary functions are to contain and protect the pelvic and abdominopelvic viscera (inferior parts of the urinary tracts, internal reproductive organs), providing attachment for external reproductive organs and associated muscles and membranes.[1]

As a mechanical structure

[edit]

The pelvic girdle consists of the two hip bones. The hip bones are connected to each other anteriorly at the pubic symphysis, and posteriorly to the sacrum at the sacroiliac joints to form the pelvic ring. The ring is very stable and allows very little mobility, a prerequisite for transmitting loads from the trunk to the lower limbs.[17]

As a mechanical structure the pelvis may be thought of as four roughly triangular and twisted rings. Each superior ring is formed by the iliac bone; the anterior side stretches from the acetabulum up to the anterior superior iliac spine; the posterior side reaches from the top of the acetabulum to the sacroiliac joint; and the third side is formed by the palpable iliac crest. The lower ring, formed by the rami of the pubic and ischial bones, supports the acetabulum and is twisted 80–90 degrees in relation to the superior ring.[18]

An alternative approach is to consider the pelvis part of an integrated mechanical system based on the tensegrity icosahedron as an infinite element. Such a system is able to withstand omnidirectional forces—ranging from weight-bearing to childbearing—and, as a low energy requiring system, is favoured by natural selection.[19]

The pelvic inclination angle is the single most important element of the human body posture and is adjusted at the hips. It is also one of the rare things that can be measured at the assessment of the posture. A simple method of measurement was described by the British orthopedist Philip Willes and is performed by using an inclinometer.

As an anchor for muscles

[edit]The lumbosacral joint, between the sacrum and the last lumbar vertebra, has, like all vertebral joints, an intervertebral disc, anterior and posterior ligaments, ligamenta flava, interspinous and supraspinous ligaments, and synovial joints between the articular processes of the two bones. In addition to these ligaments the joint is strengthened by the iliolumbar and lateral lumbosacral ligaments. The iliolumbar ligament passes between the tip of the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra and the posterior part of the iliac crest. The lateral lumbosacral ligament, partly continuous with the iliolumbar ligament, passes down from the lower border of the transverse process of the fifth vertebra to the ala of the sacrum. The movements possible in the lumbosacral joint are flexion and extension, a small amount of lateral flexion (from 7 degrees in childhood to 1 degree in adults), but no axial rotation. Between ages 2–13 the joint is responsible for as much as 75% (about 18 degrees) of flexion and extension in the lumbar spine. From age 35 the ligaments considerably limit the range of motions. [20]

The three extracapsular ligaments of the hip joint—the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments—form a twisting mechanism encircling the neck of the femur. When sitting, with the hip joint flexed, these ligaments become lax permitting a high degree of mobility in the joint. When standing, with the hip joint extended, the ligaments get twisted around the femoral neck, pushing the head of the femur firmly into the acetabulum, thus stabilizing the joint.[21] The zona orbicularis assists in maintaining the contact in the joint by acting like a buttonhole on the femoral head.[22] The intracapsular ligament, the ligamentum teres, transmits blood vessels that nourish the femoral head.[23]

Junctions

[edit]

The two hip bones are joined anteriorly at the pubic symphysis by a fibrous cartilage covered by a hyaline cartilage, the interpubic disk, within which a non-synovial cavity might be present. Two ligaments, the superior and inferior pubic ligaments, reinforce the symphysis.[3]

Both sacroiliac joints, formed between the auricular surfaces of the sacrum and the two hip bones. are amphiarthroses, almost immobile joints enclosed by very taut joint capsules. This capsule is strengthened by the ventral, interosseous, and dorsal sacroiliac ligaments.[3] The most important accessory ligaments of the sacroiliac joint are the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments which stabilize the hip bone on the sacrum and prevent the promonotory from tilting forward. Additionally, these two ligaments transform the greater and lesser sciatic notches into the greater and lesser foramina, a pair of important pelvic openings.[24] The iliolumbar ligament is a strong ligament which connects the tip of the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra to the posterior part of the inner lip of the iliac crest. It can be thought of as the lower border of the thoracolumbar fascia and is occasionally accompanied by a smaller ligamentous band passing between the fourth lumbar vertebra and the iliac crest. The lateral lumbosacral ligament is partly continuous with the iliolumbar ligament. It passes between the transverse process of the fifth vertebra to the ala of the sacrum where it intermingle with the anterior sacroiliac ligament.[25]

The joint between the sacrum and the coccyx, the sacrococcygeal symphysis, is strengthened by a series of ligaments. The anterior sacrococcygeal ligament is an extension of the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) that run down the anterior side of the vertebral bodies. Its irregular fibers blend with the periosteum. The posterior sacrococcygeal ligament has a deep and a superficial part, the former is a flat band corresponding to the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) and the latter corresponds to the ligamenta flava. Several other ligaments complete the foramen of the last sacral nerve.[26]

Shoulder and intrinsic back

[edit]

The inferior parts of latissimus dorsi, one of the muscles of the upper limb, arises from the posterior third of the iliac crest.[27] Its action on the shoulder joint are internal rotation, adduction, and retroversion. It also contributes to respiration (i.e. coughing).[28] When the arm is adducted, latissimus dorsi can pull it backward and medially until the back of the hand covers the buttocks.[27]

In a longitudinal osteofibrous canal on either side of the spine there is a group of muscles called the erector spinae which is subdivided into a lateral superficial and a medial deep tract. In the lateral tract, the iliocostalis lumborum and longissimus thoracis originates on the back of the sacrum and the posterior part of the iliac crest. Contracting these muscles bilaterally extends the spine and unilaterally contraction bends the spine to the same side. The medial tract has a "straight" (interspinales, intertransversarii, and spinalis) and an "oblique" (multifidus and semispinalis) component, both of which stretch between vertebral processes; the former acts similar to the muscles of the lateral tract, while the latter function unilaterally as spine extensors and bilaterally as spine rotators. In the medial tract, the multifidi originates on the sacrum.[29]

Abdomen

[edit]The muscles of the abdominal wall are subdivided into a superficial and a deep group.

The superficial group is subdivided into a lateral and a medial group. In the medial superficial group, on both sides of the centre of the abdominal wall (the linea alba), the rectus abdominis stretches from the cartilages of ribs V-VII and the sternum down to the pubic crest. At the lower end of the rectus abdominis, the pyramidalis tenses the linea alba. The lateral superficial muscles, the transversus and external and internal oblique muscles, originate on the rib cage and on the pelvis (iliac crest and inguinal ligament) and are attached to the anterior and posterior layers of the sheath of the rectus.[30]

Flexing the trunk (bending forward) is essentially a movement of the rectus muscles, while lateral flexion (bending sideways) is achieved by contracting the obliques together with the quadratus lumborum and intrinsic back muscles. Lateral rotation (rotating either the trunk or the pelvis sideways) is achieved by contracting the internal oblique on one side and the external oblique on the other. The transversus' main function is to produce abdominal pressure in order to constrict the abdominal cavity and pull the diaphragm upward.[30]

There are two muscles in the deep or posterior group. Quadratus lumborum arises from the posterior part of the iliac crest and extends to the rib XII and lumbar vertebrae I–IV. It unilaterally bends the trunk to the side and bilaterally pulls the 12th rib down and assists in expiration. The iliopsoas consists of psoas major (and occasionally psoas minor) and iliacus, muscles with separate origins but a common insertion on the lesser trochanter of the femur. Of these, only iliacus is attached to the pelvis (the iliac fossa). However, psoas passes through the pelvis and because it acts on two joints, it is topographically classified as a posterior abdominal muscle but functionally as a hip muscle. Iliopsoas flexes and externally rotates the hip joints, while unilateral contraction bends the trunk laterally and bilateral contraction raises the trunk from the supine position.[31]

Hip and thigh

[edit]

|

|

| |

| Muscles of the hip. Anterior view for the top-left and right diagrams. Posterior view for the bottom-left diagram | |

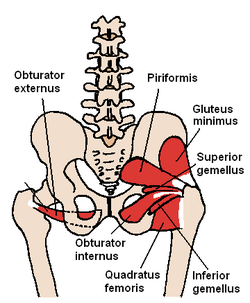

The muscles of the hip are divided into a dorsal and a ventral group.

The dorsal hip muscles are either inserted into the region of the lesser trochanter (anterior or inner group) or the greater trochanter (posterior or outer group). Anteriorly, the psoas major (and occasionally psoas minor) originates along the spine between the rib cage and pelvis. The iliacus originates on the iliac fossa to join psoas at the iliopubic eminence to form the iliopsoas which is inserted into the lesser trochanter.[32] The iliopsoas is the most powerful hip flexor.[33]

The posterior group includes the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus. Maximus has a wide origin stretching from the posterior part of the iliac crest and along the sacrum and coccyx, and has two separate insertions: a proximal which radiates into the iliotibial tract and a distal which inserts into the gluteal tuberosity on the posterior side of the femoral shaft. It is primarily an extensor and lateral rotator of the hip joint, but, because of its bipartite insertion, it can both adduct and abduct the hip. Medius and minimus arise on the external surface of the ilium and are both inserted into the greater trochanter. Their anterior fibers are medial rotators and flexors while the posterior fibers are lateral rotators and extensors. The piriformis has its origin on the ventral side of the sacrum and is inserted on the greater trochanter. It abducts and laterally rotates the hip in the upright posture and assists in extension of the thigh.[32] The tensor fasciae latae arises on the anterior superior iliac spine and inserts into the iliotibial tract.[34] It presses the head of the femur into the acetabulum and flexes, medially rotates, and abducts the hip.[32]

The ventral hip muscles are important in the control of the body's balance. The internal and external obturator muscles together with the quadratus femoris are lateral rotators of the hip. Together they are stronger than the medial rotators and therefore the feet point outward in the normal position to achieve a better support. The obturators have their origins on either sides of the obturator foramen and are inserted into the trochanteric fossa on the femur. Quadratus arises on the ischial tuberosity and is inserted into the intertrochanteric crest. The superior and inferior gemelli, arising from the ischial spine and ischial tuberosity respectively, can be thought of as marginal heads of the obturator internus, and their main function is to assist this muscle.[32]

The muscles of the thigh can be subdivided into adductors (medial group), extensors (anterior group), and flexors (posterior group). The extensors and flexors act on the knee joint, while the adductors mainly act on the hip joint.

The thigh adductors have their origins on the inferior ramus of the pubic bone and are, with the exception of gracilis, inserted along the femoral shaft. Together with sartorius and semitendinosus, gracilis reaches beyond the knee to their common insertion on the tibia.[35]

The anterior thigh muscles form the quadriceps which is inserted on the patella with a common tendon. Three of the four muscles have their origins on the femur, while rectus femoris arises from the anterior inferior iliac spine and is thus the only of the four acting on two joints.[36]

The posterior thigh muscles have their origins on the inferior ischial ramus, with the exception of the short head of the biceps femoris. The semitendinosus and semimembranosus are inserted on the tibia on the medial side of the knee, while biceps femoris is inserted on the fibula, on the knee's lateral side.[37]

In pregnancy and childbirth

[edit]In later stages of pregnancy the fetus's head aligns inside the pelvis.[38] Also joints of bones soften due to the effect of pregnancy hormones.[39] These factors may cause pelvic joint pain (symphysis pubis dysfunction or SPD).[40][41] As the end of pregnancy approaches, the ligaments of the sacroiliac joint loosen, letting the pelvis outlet widen somewhat; this is easily noticeable in the cow.

During childbirth (unless by Cesarean section) the fetus passes through the maternal pelvic opening.[42]

Clinical significance

[edit]Hip fractures often affect the elderly and occur more often in females; this is frequently due to osteoporosis. There are also different types of pelvic fracture, often resulting from traffic accidents.

Pelvic pain can affect anybody and has a variety of causes, including bowel adhesions, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and endometriosis in women.

There are many anatomical variations of the pelvis. In the female the pelvis can be of a much larger size than normal, known as a giant pelvis or pelvis justo major, or it can be much smaller, known as a reduced pelvis or pelvis justo minor.[43] Other variations include an android pelvis, a pelvis of the normal male shape in a female, which can prove problematic in childbirth.

History

[edit]Caldwell–Moloy classification

[edit]Throughout the 20th century pelvimetric measurements were made on pregnant women to determine whether a natural birth would be possible, a practice today limited to cases where a specific problem is suspected or following a caesarean delivery. William Edgar Caldwell and Howard Carmen Moloy studied collections of skeletal pelves and thousands of stereoscopic radiograms and finally recognized three types of female pelves plus the masculine type. In 1933 and 1934 they published their typology, including the Greek names since then frequently quoted in various handbooks: Gynaecoid (gyne, woman), anthropoid (anthropos, human being), platypelloid (platys, flat), and android (aner, man).[44][45]

- The gynaecoid pelvis is the so-called normal female pelvis. Its inlet is either slightly oval, with a greater transverse diameter, or round. The interior walls are straight, the subpubic arch wide, the sacrum shows an average to backward inclination, and the greater sciatic notch is well rounded. Because this type is spacious and well proportioned there is little or no difficulty in the birth process. Caldwell and his co-workers found gynaecoid pelves in about 50 per cent of specimens. This gives a round shape to the gluteus region, circle shape to hip region, and circle shape side way profile https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519068/#

- The platypelloid pelvis has a transversally wide, flattened shape, is wide anteriorly, greater sciatic notches of male type, and has a short sacrum that curves inwards reducing the diameters of the lower pelvis. This is similar to the rachitic pelvis where the softened bones widen laterally because of the weight from the upper body resulting in a reduced anteroposterior diameter. Giving birth with this type of pelvis is associated with problems, such as transverse arrest. Less than 3 per cent of women have this pelvis type. This gives an inverted triangle shape to the gluteus region, hip region and straight sideway profile https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519068/#

- The android pelvis is a female pelvis with masculine features, including a wedge or heart shaped inlet caused by a prominent sacrum and a triangular anterior segment. The reduced pelvis outlet often causes problems during child birth. In 1939 Caldwell found this type in one-third of white women and in one-sixth of non-white women. The android pelvis is found in the vast majority of subsaharan african women . The android pelvis gives the human skeleton a triangle shape looking at it from the front and a android shape looking at it from the back these features result in giving steatopygia the basis of its unique specific shape with added relation to the femur.[46] also gives a trapezoidal shape to the gluteus region, hip region, and side way profile https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519068/# This trapezoidal shape is what gives the genetic characteristic steatopygia its specific shape.

- The anthropoid pelvis is characterized by an oval shape with a greater anteroposterior diameter. It has straight walls, a small subpubic arch, and large sacrosciatic notches. The sciatic spines are placed widely apart and the sacrum is usually straight resulting in deep non-obstructed pelvis. Caldwell found this type in one-quarter of white women and almost half of non-white women.[47] This gives a square shape to the gluteus region, also hip region and side way profile https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519068/#

However, Caldwell and Moloy then complicated this simple fourfold scheme by dividing the pelvic inlet into posterior and anterior segments. They named a pelvis according to the anterior segment and affixed another type according to the character of the posterior segment (i.e. anthropoid-android) and ended up with no less than 14 morphologies. Notwithstanding the popularity of this simple classification, the pelvis is much more complicated than this as the pelvis can have different dimensions at various levels of the birth canal.[48]

Caldwell and Moloy also classified the physique of women according to their types of pelves: the gynaecoid type has small shoulders, a small waist and wide hips; the android type looks square-shaped from behind; and the anthropoid type has wide shoulders and narrow hips.[49] Lastly, in their article they described all non-gynaecoid or "mixed" types of pelves as "abnormal", a word which has stuck in the medical world even though at least 50 per cent of women have these "abnormal" pelves.[50]

The classification of Caldwell and Moloy was influenced by earlier classifications attempting to define the ideal female pelvis, treating any deviations from this ideal as dysfunctions and the cause of obstructed labour. In the 19th century anthropologists and others saw an evolutionary scheme in these pelvic typologies, a scheme since then refuted by archaeology. Since the 1950s malnutrition is thought to be one of the chief factors affecting pelvic shape in the Third World even though there are at least some genetic component to variation in pelvic morphology.[51]

Nowadays obstetric suitability of the female pelvis is assessed by ultrasound. The dimensions of the head of the fetus and of the birth canal are accurately measured and compared, and the feasibility of labor can be predicted.

Other animals

[edit]

The pelvic girdle was present in early vertebrates, and can be tracked back to the paired fins of fish that were some of the earliest chordates.[52]

The shape of the pelvis, most notably the orientation of the iliac crests and shape and depth of the acetabula, reflects the style of locomotion and body mass of an animal. In bipedal mammals, the iliac crests are parallel to the vertically oriented sacroiliac joints, where in quadrupedal mammals they are parallel to the horizontally oriented sacroiliac joints. In heavy mammals, especially in quadrupeds, the pelvis tend to be more vertically oriented because this allows the pelvis to support greater weight without dislocating the sacroiliac joints or adding torsion to the vertebral column.

In ambulatory mammals, the acetabula are shallow and open to allow a wider range of hip movements, including significant abduction, than in cursorial mammals. The lengths of the ilium and ischium and their angles relative to the acetabulum are functionally important as they determine the moment arms for the hip extensor muscles that provide momentum during locomotion.[53]

In addition to this, the relatively wide shape (front to back) of the pelvis provides greater leverage for the gluteus medius and minimus. These muscles are responsible for hip abduction which plays an integral role in upright balance.

Primates

[edit]In primates, the pelvis consists of four parts - the left and the right hip bones which meet in the mid-line ventrally and are fixed to the sacrum dorsally and the coccyx. Each hip bone consists of three components, the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis, and at the time of sexual maturity these bones become fused together, though there is never any movement between them. In humans, the ventral joint of the pubic bones is closed.

Larger apes, such as Pongo (orangutans), Gorilla (gorillas), Australopithecus afarensis, and Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees), have longer three-pelvic planes with a maximum diameter in the sagittal plane.[54]

Evolution

[edit]The present-day morphology of the pelvis is inherited from the pelvis of our quadrupedal ancestors. The most striking feature of evolution of the pelvis in primates is the widening and the shortening of the blade called the ilium. Because of the stresses involved in bipedal locomotion, the muscles of the thigh move the thigh forward and backward, providing the power for bi-pedal and quadrupedal locomotion.[55]

The drying of the environment of East Africa in the period since the creation of the Red Sea and the African Rift Valley saw open woodlands replace the previous closed canopy forest. The apes in this environment were compelled to travel from one clump of trees to another across open country. This led to a number of complementary changes to the human pelvis. It is suggested that bipedalism was the result.

Additional images

[edit]-

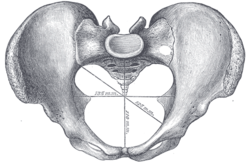

Diameters of pelvic inlet

-

Right hip bone. External surface.

-

Pelvic girdle anatomy

See also

[edit]- Coccygeal plexus – Nerve plexus near the coccyx bone

- Coccyx (tailbone) – Bone of the pelvis

- Pelvimetry – Measurement of the female pelvis

- Pelvis justo major – Congenitally large female pelvis of normal shape

- Pubic symphysis – Cartilaginous joint between the front of the left and right hip bones

- Sacroiliac joint – Joint of the pelvis and spine

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Moore 2014, pp. 357–8.

- ^ "Gray's anatomy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-24. Retrieved 2014-12-20.

- ^ a b c Platzer (2004), p. 188

- ^ Betti, Lia (March 17, 2017). "Human variation in pelvic shape and the effects of climate and past population history". The Anatomical Record. 300 (4): 687–97. doi:10.1002/ar.23542. PMID 28297180.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 137

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 106

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 136

- ^ "Gynecoid pelvis". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 2016-08-21. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Merry 2005, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Thieme Atlas of Anatomy, (2006), p. 113

- ^

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (2013). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 8.3 The pelvic girdle and pelvis. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (2013). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 8.3 The pelvic girdle and pelvis. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ Merry 2005, pp. 50–1.

- ^ a b c d e Merry 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Merry 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Masi AT, Carreiro JE, Danneels L, Willard FH (December 2012). "The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications". Journal of Anatomy (Review). 221 (6): 537–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01564.x. PMC 3512279. PMID 22994881.

- ^ Berger AA, May R, Renner JB, Viradia N, Dahners LE (November 2011). "Surprising evidence of pelvic growth (widening) after skeletal maturity". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 29 (11): 1719–23. doi:10.1002/jor.21469. PMID 21608025. S2CID 19401628.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 112

- ^ Holm (1980), pp. 425–6

- ^ Levin (2003), A Different Approach to the Mechanics of the Human Pelvis: Tensegrity (See conclusions.)

- ^ Palastanga (2006), pp. 331–2

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 381

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 198

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 383

- ^ Palastanga (2006), pp. 326–7

- ^ Palastanga (2006), pp. 332–3

- ^ Morris (2005), p. 59

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 140

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 266

- ^ Platzer (2004), pp. 72, 74

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), pp. 84–91

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 128

- ^ a b c d Platzer (2004), p. 234

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 422.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 424

- ^ Platzer (2004), pp. 240–3

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 248

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 250

- ^ "When should my baby's head engage? If it engages early does that mean I am going to give birth early?". BabyCentre. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Pelvic Pain during Pregnancy". Baby Care Guide. Archived from the original on 2009-03-21. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Female Pelvic Pain". Pain relief medication. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Pelvic Pain (Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction)". Plus-Size Pregnancy Website. April 2003. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Part 2 – Labor and Delivery". Ask Dr Amy. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Justo major pelvis". Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ^ Merry 2005, pp. 52–4.

- ^ Caldwell, W. E.; Moloy, H. C. (1938). "Anatomical Variations in the Female Pelvis: Their Classification and Obstetrical Significance: (Section of Obstetrics and Gynaecology)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 32 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1177/003591573803200101. PMC 1997320. PMID 19991699.

- ^ Nakabuye, Mariam; Kamiza, Abram Bunya; Soremekun, Opeyemi; Machipisa, Tafadzwa; Cohen, Emmanuel; Pirie, Fraser; Nashiru, Oyekanmi; Young, Elizabeth; Sandhu, Manjinder S.; Motala, Ayesha A.; Chikowore, Tinashe; Fatumo, Segun (2022-06-01). "Genetic loci implicated in meta-analysis of body shape in Africans". Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 32 (6): 1511–1518. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2022.03.010. ISSN 0939-4753.

- ^ Merry 2005, pp. 55–6.

- ^ Merry 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Merry 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Merry 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Merry 2005, pp. 58–9.

- ^ Gregory, William K. (1935). "The pelvis from fish to man: a study in paleomorphology". The American Naturalist. 69 (722): 193–210. doi:10.1086/280593. JSTOR 2456838. S2CID 85158234.

- ^ Hall (2007), pp. 254–5

- ^ Sreekanth, R (September 2015). "Human evolution: the real cause for birth palsy". West Indian Medical Journal. 64 (4): 424–8. doi:10.7727/wimj.2014.083 (inactive 12 July 2025). PMC 4909080. PMID 26624599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Bernard Grant Campbell (1998). Human Evolution: An Introduction to Mans Adaptations. Transaction Publishers. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-202-02042-6. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

References

[edit]- Cunningham, Daniel John; Robinson, Arthur (1818). Cunningham's text-book of anatomy. William Wood and company. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- Ebrall, Phillip S.; Sportelli, Louis; Donato, Phillip R. (2004). Assessment of the Spine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-443-07228-4. Retrieved 2010-08-14.[permanent dead link]

- Hall, Brian Keith (2007). Fins into limbs: evolution, development, and transformation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31337-5. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- Holm, Niels J. (1980). "The Internal Stress Pattern of the os Coxae". Acta Orthopaedica. 51 (1): 421–8. doi:10.3109/17453678008990818. PMID 7446021.

- Levin, Stephen M. (2007). "Hang In There!: The Statics and Dynamics of Pelvic Mechanics". Biotensegrity. Archived from the original on 2010-06-10.

- Merry, Clare V. (2005). "Pelvic Shape". Mind – Primary Cause of Human Evolution. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4120-5457-5. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- Moore, Keith L. (2014). Clinically oriented anatomy. Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-1945-9.

- Morris, Craig E. (2005). Low Back Syndromes: Integrated Clinical Management. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-137472-9.

- Palastanga, Nigel; Field, Derek; Soames, Roger (2006). Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-7506-8814-7.

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. 2006. ISBN 978-1-58890-419-5.