Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ps (Unix)

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| ps | |

|---|---|

The ps command | |

| Original author | AT&T Bell Laboratories |

| Developers | Various open-source and commercial developers |

| Initial release | February 1973 |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Unix, Unix-like, Plan 9, Inferno, KolibriOS, IBM i |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Type | Command |

| License | Plan 9: MIT License |

In most Unix and Unix-like operating systems, the ps (process status) program displays the currently-running processes. The related Unix utility top provides a real-time view of the running processes.

Implementations

[edit]KolibriOS includes an implementation of the ps command.[1] The ps command has also been ported to the IBM i operating system.[2] In Windows PowerShell, ps is a predefined command alias for the Get-Process cmdlet, which essentially serves the same purpose.

Examples

[edit]# ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

7431 pts/0 00:00:00 su

7434 pts/0 00:00:00 bash

18585 pts/0 00:00:00 ps

Users can pipeline ps with other commands, such as less to view the process status output one page at a time:

$ ps -A | less

Users can also utilize the ps command in conjunction with the grep command (see the pgrep and pkill commands) to find information about a single process, such as its id:

$ # Trying to find the PID of `firefox-bin` which is 2701

$ ps -A | grep firefox-bin

2701 ? 22:16:04 firefox-bin

The use of pgrep simplifies the syntax and avoids potential race conditions:

$ pgrep -l firefox-bin

2701 firefox-bin

To see every process running as root in user format:

# ps -U root -u

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TT STAT STARTED TIME COMMAND

root 1 0.0 0.0 9436 128 - ILs Sun00AM 0:00.12 /sbin/init --

Header line

[edit]| Column Header | Contents |

|---|---|

| %CPU | How much of the CPU the process is using |

| %MEM | How much memory the process is using |

| ADDR | Memory address of the process |

| C or CP | CPU usage and scheduling information |

| COMMAND* | Name of the process, including arguments, if any |

| NI | nice value |

| F | Flags |

| PID | Process ID number |

| PPID | ID number of the process's parent process |

| PRI | Priority of the process |

| RSS | Resident set size |

| S or STAT | Process status code |

| START or STIME | Time when the process started |

| VSZ | Virtual memory usage |

| TIME | The amount of CPU time used by the process |

| TT or TTY | Terminal associated with the process |

| UID or USER | Username of the process's owner |

| WCHAN | Memory address of the event the process is waiting for |

* = Often abbreviated

Options

[edit]ps has many options. On operating systems that support the SUS and POSIX standards, ps commonly runs with the options -ef, where "-e" selects every process and "-f" chooses the "full" output format. Another common option on these systems is -l, which specifies the "long" output format from X/Open System Interfaces (XSI), an optional extension to POSIX.

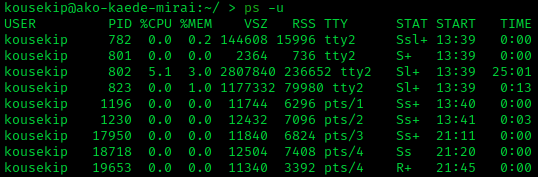

Most systems derived from BSD fail to accept the SUS and POSIX standard options because of historical conflicts. (For example, the "e" or "-e" option will display environment variables.) On such systems, ps commonly runs with the non-standard options aux, where "a" lists all processes on a terminal, including those of other users, "x" lists all processes without controlling terminals and "u" adds a column for the controlling user for each process. For maximum compatibility, there is no "-" in front of the "aux". "ps auxww" provides complete information about the process, including all parameters.

See also

[edit]- Task manager

- kill (command)

- List of Unix commands

- nmon – a system monitor tool for AIX and Linux operating systems

- pstree (Unix)

- lsof

References

[edit]- ^ "Shell - KolibriOS wiki". Archived from the original on 2019-02-11. Retrieved 2019-08-11.

- ^ IBM. "IBM System i Version 7.2 Programming Qshell" (PDF). IBM. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2020-09-05.

Further reading

[edit]- McElhearn, Kirk (2006). The Mac OS X Command Line: Unix Under the Hood. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470113851.

- Shotts (Jr), William E. (2012). The Linux Command Line: A Complete Introduction. No Starch Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 9781593273897. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

External links

[edit]- – Shell and Utilities Reference, The Single UNIX Specification, Version 5 from The Open Group

- – Plan 9 Programmer's Manual, Volume 1

- – Inferno General commands Manual

- Show all running processes in Linux using ps command

- In Unix, what do the output fields of the ps command mean?

Ps (Unix)

View on Grokipediaps (process status) is a command-line utility in Unix and Unix-like operating systems that reports a snapshot of the current active processes, displaying key information such as the process ID (PID), terminal (TTY), cumulative CPU time (TIME), and the command name or executable (CMD).[1][2] By default, it lists only the processes associated with the invoking user's effective user ID and controlling terminal, but options allow selection of all processes or specific subsets based on criteria like user, group, or session.[1][2]

The command supports multiple syntax styles to accommodate historical variations: Unix-style options (prefixed with a single dash, e.g., -e), BSD-style (no dash, e.g., aux), and GNU long options (double dash, e.g., --sort).[2] Common options include -A or -e to show all processes, -f for a full-format listing with parent process ID (PPID) and start time, and -o for custom output formats specifying fields like user ID, priority, or memory usage.[1][2] Output can be sorted by criteria such as CPU usage or memory, and the utility conforms to POSIX.1-2004 standards, ensuring portability across compliant systems.[1][2]

Originally part of the foundational Unix utilities, ps was first defined in POSIX Issue 2 and has been enhanced over time, with modern implementations like those in the procps-ng project adding support for thread display, security contexts (e.g., SELinux), and integration with the /proc filesystem for accurate process data retrieval.[1][2] It remains essential for system administration tasks, such as monitoring resource usage, diagnosing performance issues, and identifying processes for termination via the kill command.[2]

Introduction

Overview

Theps command is a command-line utility in Unix-like operating systems that displays information about active processes on the system. It provides a snapshot of running processes, typically including key details such as the process ID (PID), the associated controlling terminal, cumulative CPU time consumed, and the name or command line of the process.[2] This output helps users identify and examine the state of programs executing in the kernel's process table.

At its core, ps reports on a selection of processes based on criteria like user ownership or terminal association, with options allowing customization to include additional attributes such as memory usage, priority, or start time. The command does not monitor processes continuously but captures a static view at the moment of invocation, making it suitable for one-off diagnostics rather than real-time observation.[2] Privileges may restrict access to information about certain processes, ensuring security in multi-user environments.

In system administration, ps plays an essential role for monitoring resource utilization, debugging application issues, and managing running programs across Unix, Linux, macOS, and other POSIX-compliant systems. It enables administrators to locate problematic processes, assess system load, and prepare for actions like termination via complementary tools.[2] First released in February 1973 by AT&T Bell Laboratories as part of early Unix development, ps has become a foundational utility in process management.[3]

History

The ps command was developed at AT&T Bell Laboratories in 1973 as part of Version 3 Unix, providing an early mechanism for reporting the status of active processes on the system, as documented in the February 1973 Unix Programmer's Manual.[3] Unix's process management concepts drew from ideas pioneered in the Multics operating system, where key Unix developers had earlier contributed to multi-user handling facilities.[4] Version 4 Unix, released later in November 1973, marked a significant shift with the kernel rewritten in the C programming language to improve portability across hardware platforms. A key milestone occurred in 1977 with its inclusion in the first Berkeley Software Distribution (1BSD), which extended the original AT&T implementation by adding user-oriented options such as 'u' for detailed user-specific output and 'a' for processes across all terminals, making it more practical for interactive use. These enhancements reflected BSD's focus on usability for academic and research environments. The command's portability was further solidified by its inclusion in the IEEE POSIX.1-1988 standard, which defined a core set of options like '-e' for all processes and '-f' for full format to ensure consistent behavior across conforming Unix systems. In the 1990s, the Single UNIX Specification (SUS) built on POSIX by incorporating additional extensions, such as support for wide-character locales and enhanced output formatting, to address evolving system requirements in commercial Unix variants. The command's evolution also saw a transition from proprietary AT&T code to open-source implementations; BSD distributions released ps under open licenses starting in the 1980s, while Linux adopted and extended it in the early 1990s. Notably, Plan 9 from Bell Labs, developed in the early 1990s and open-sourced around 2000, included a ps variant under a permissive license akin to the MIT license, facilitating broader adoption and modification in distributed computing contexts. By 2025, the ps command has been in use for over 50 years, exemplifying the longevity of Unix's foundational process model amid ongoing adaptations in modern operating systems.Usage

Syntax

Theps command follows the general syntax ps [options] [select], where options modify the output format, sorting, and other display behaviors, while select criteria specify which processes to report on.[1] This structure allows flexible invocation, with options drawn from POSIX-defined flags such as -a, -d, -e, -f, -l, -g, -G, -o, -p, -t, -u, and -U, among others.[1]

When invoked without any arguments, ps defaults to displaying only those processes that share the invoker's effective user ID and are associated with the same controlling terminal.[1] In this mode, the output includes standard fields like process ID (PID), terminal identifier (TTY), cumulative CPU time (TIME), and command name (CMD), presented without sorting.[2]

The command accepts three main argument types: the no-select form, which relies solely on output-modifying options like -o for custom formats; the select form, which uses process-specification options such as -p for PID lists or -u for user-based selection; and the combined form, integrating both to filter and format results simultaneously.[2] POSIX compliance mandates support for these forms through the specified options in IEEE Std 1003.1, ensuring portability across conforming systems.[1]

As a standard Unix utility, ps is executed from a shell environment like sh or bash, where it interacts with shell-set variables such as COLUMNS to adjust output width and LC_TIME for time formatting, assuming basic familiarity with shell invocation and option parsing.[2]

Process Selection

Theps command in Unix-like systems selects processes for display based on specific criteria, allowing users to filter output according to identifiers such as process ID (PID), user, or terminal association. By default, ps selects all processes with the same effective user ID (EUID) as the current user and associated with the same controlling terminal as the invoker, providing a focused view of the invoking user's interactive processes without requiring additional options.[1][2]

Selection criteria can be specified individually or in combination using options that perform an inclusive OR operation, overriding the default selection when any are provided. Processes can be selected by PID using the -p option followed by a list of process IDs (e.g., -p 1234), which targets specific running processes regardless of ownership or terminal.[1] User-based selection is achieved with -u for effective user ID or login name (e.g., -u username), or -U for real user ID, enabling display of processes owned by designated users.[1] Terminal selection uses -t with a list of terminal identifiers (e.g., -t pts/0), restricting output to processes attached to specified devices like pseudoterminals or console lines.[1] In BSD-style implementations, such as FreeBSD, these options support comma-separated lists for multiple values (e.g., -p 1234,5678 or -u user1,user2), facilitating efficient selection of several PIDs or users in a single invocation.[5]

Advanced selectors extend filtering to job control and related attributes in POSIX-compliant systems. The -g option selects processes by session leaders (e.g., -g grouplist), useful for identifying job control groups in environments with shell job management.[1] Effective user ID criteria are inherently tied to the -u option, while session ID can be indirectly addressed through session leader selection or output fields in job control modes like -j, which displays details such as process group ID (PGID) and session ID (SID).[1][5]

Limitations in process selection arise from system constraints and security models. In many implementations, kernel threads often cannot be selected using standard user or terminal criteria because they lack a controlling terminal and are typically not owned by regular user IDs, though they can be selected by PID if known; however, they may appear in all-process listings (e.g., with -e in Linux) if supported.[2] Additionally, selecting processes owned by other users requires appropriate permissions, such as root privileges, to access restricted process information; unprivileged users are typically limited to their own processes or those explicitly permitted by the system.[6]

Output

Standard Fields

Theps command in Unix-like systems displays a snapshot of current processes, with its standard output consisting of core fields that provide essential information about each process. These fields are derived from kernel data structures, such as the /proc filesystem in Linux or equivalent mechanisms in other Unix variants, which expose process metadata without requiring special privileges.[1][2]

According to the POSIX standard, the basic output (without options) must include at least the PID, TTY, TIME, and CMD fields to ensure portability across conforming systems. Common implementations often display additional fields such as UID (the effective user identifier under which the process runs, often as a numeric ID or username), PPID (the process identifier of the parent process), and others. The PID serves as the fundamental unique identifier for process management tasks like signaling or termination. TTY indicates the controlling terminal associated with the process (or a marker like ? for no terminal). TIME represents the cumulative CPU time consumed by the process in a formatted string such as mm:ss or dd-hh:mm:ss, accumulating the total processor usage across all CPU cores and excluding I/O wait times. CMD is the name of the command or executable that started the process.[1][2]

A common field in extended listings (e.g., the long format with -l) is STAT, which encodes the process state using one or more characters to indicate its current status, such as R for running or runnable, S for interruptible sleep (waiting for an event), D for uninterruptible sleep (typically I/O bound), Z for zombie (terminated but not yet reaped by the parent), and T for stopped (e.g., by a signal).[1][2] These state codes are implementation-defined but follow common conventions across Unix systems to reflect kernel process scheduling and lifecycle stages.[1]

Some fields, such as %CPU (percentage of CPU utilization) and %MEM (percentage of physical memory used by the process's resident set), are optional and vary by implementation, often requiring specific options to display and computed dynamically from kernel statistics.[2] These core fields are typically presented in a tabular format with headers, as detailed in the relevant output formatting guidelines.[1]

Header Line

The header line in theps command output provides column labels aligned above the corresponding data rows for process information, facilitating readability of the tabular format. In the standard Unix implementation, the default header typically displays labels such as PID (process ID), TTY (controlling terminal), TIME (cumulative CPU time), and CMD (command name), with these labels positioned to match the width and alignment of the fields below them.[7]

According to POSIX requirements, headers must be included in the output unless explicitly suppressed, and the labels for standard fields—such as PID, TTY, TIME, and CMD—must use exact predefined text without alteration, ensuring portability across compliant systems. Field alignment in the header follows the data: numeric fields like PID and TIME are right-justified, while text fields like CMD are left-justified, with column widths determined by the longest header label or data entry, typically at least as wide as the header itself.[7]

Customization of the header is possible through format options; for instance, the -o flag allows modification by appending custom text to labels (e.g., -o pid=Process ID) or suppression of specific headers by setting them to null (e.g., -o user=), while wide output modes like -w prevent truncation of command lines in the CMD field, potentially extending the header alignment accordingly. In BSD variants, the aux format includes additional default headers such as USER (username) and %CPU (CPU usage percentage) alongside standard ones like PID, TT (terminal), STAT (state), TIME, and COMMAND, providing a more detailed view by default.[7][8]

Options

POSIX and SUS Options

The POSIX and SUS specifications provide a standardized set of options for theps command, enabling consistent behavior across compliant Unix-like systems for selecting and displaying process information. These options emphasize portability, with core functionality focused on process selection and basic formatting to avoid implementation-specific variations. The base POSIX options include mechanisms for specifying processes by user, group, terminal, or process ID, while SUS (Single UNIX Specification) extensions, marked as XSI (X/Open System Interfaces), add enhanced formatting and selection capabilities.[9]

Core selection options include -A to report information for all processes on the system and -e, an XSI extension equivalent to -A, which also displays all processes. For formatting, -f generates a full listing that includes the effective user ID (displayed as the login name) and the start time of the command, while -l produces a long listing with additional details such as process flags, state (e.g., running, sleeping), nice value, and priority. The -o format option allows for user-defined output specifications, where fields like pid (process ID) and comm (command name) can be selected explicitly, as in ps -o pid,comm to display only those columns. These options allow users to obtain comprehensive views without relying on non-standard features.[9]

SUS extensions further refine selection and output, with -u userlist delivering user-oriented output for specified users, incorporating metrics like %CPU (percentage of CPU time used since start) and %MEM (percentage of physical memory used).[9]

Portability is supported through single-dash syntax, allowing combined options like -ef to select all processes (-e) in full format (-f), which resolves potential conflicts with BSD-style multi-character options like aux. This design ensures scripts and applications remain interoperable across systems. The options are formally defined in POSIX.1-2001 and SUSv3, balancing standardization with essential functionality while excluding some vendor-specific historical features to promote cross-platform reliability.[9]

BSD Options

The BSD options for theps command employ a dashless syntax, enabling multiple single-letter flags to be concatenated without hyphens, a convention that originated in the Berkeley Software Distribution to facilitate grouped specifications and compatibility with earlier UNIX variants. This approach predates POSIX standardization and allows for concise commands like aux while avoiding conflicts with the single-hyphen options common in AT&T-derived systems.[5]

Introduced in 4.3BSD in 1986, these options provide flexible process selection and formatting tailored to user needs in BSD-derived environments. The a option displays all processes associated with terminals across all users, the u option produces a user-oriented output with headers including fields such as percentage CPU usage, percentage memory, virtual memory size (VSZ in KiB), and resident set size (RSS in KiB), the x option includes processes lacking controlling terminals (such as daemons), and the w option generates wide output using at least 131 columns, with repeated w flags enabling unlimited width to prevent command line truncation.[5]

A widely used combination, aux, integrates a, u, and x to list all processes in the user format, including terminal-less ones, offering a comprehensive view with memory details like RSS for physical memory allocation and VSZ for total address space. Extending to auxww further ensures full command visibility without width limits. These options persist as the primary interface in modern BSD systems like FreeBSD and macOS, where they default over POSIX alternatives for legacy and usability reasons.[5]

Examples

Basic Usage

Theps command in its simplest form provides a snapshot of active processes, particularly useful for inspecting those tied to the current terminal and user without additional configuration. When invoked without arguments, ps displays only the processes with the same effective user ID and terminal as the invoking shell, using a default set of fields such as process ID (PID), terminal (TTY), cumulative CPU time (TIME), and command name (CMD).[2]

For example, executing ps in an interactive shell might yield output like the following:

PID TTY TIME CMD

1234 pts/0 00:00:01 bash

PID TTY TIME CMD

1234 pts/0 00:00:01 bash

-f option enables a full-format listing for the current user's processes, adding fields like user ID (UID), parent process ID (PPID), processor utilization (C), start time (STIME), and the full command with arguments. A typical output from ps -f could appear as:

UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD

user 1234 1233 0 10:00 pts/0 00:00:01 /bin/bash

UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD

user 1234 1233 0 10:00 pts/0 00:00:01 /bin/bash

-u option, such as ps -u root, restricts the display to processes owned by that user, which is helpful for examining system daemons or privileged tasks; it uses a user-oriented format with fields including CPU and memory usage (%CPU, %MEM), virtual and resident set sizes (VSZ, RSS), status (STAT), and start time (START). An example output might include:

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

root 1 0.0 0.1 18592 4128 ? Ss Nov13 0:01 /lib/systemd/systemd

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

root 1 0.0 0.1 18592 4128 ? Ss Nov13 0:01 /lib/systemd/systemd

Advanced Filtering

Advanced filtering of process information with theps command often involves piping its output to other Unix utilities like grep, sort, and xargs, enabling targeted inspection without displaying the entire process list. This approach leverages shell pipelines to process and refine the output dynamically, which is particularly useful for system administrators monitoring specific patterns, resource hogs, or process relationships. By combining ps with these tools, users can avoid manual sifting through voluminous data, promoting efficiency in troubleshooting and automation tasks.[10]

A common technique is to filter for processes matching a keyword, such as those related to a web server. For instance, the command ps -A | grep apache lists all processes (-A) and pipes the output to grep to show only lines containing "apache", revealing associated process IDs and commands without scanning the full system output. This method is efficient for quick checks on service status in administrative workflows.[10]

To identify resource-intensive processes, output can be sorted by metrics like CPU usage. The command ps aux | sort -nrk 4 | head -5 displays all processes in BSD-style format (aux), sorts them numerically in reverse order (-nr) by the fourth column (%CPU), and limits to the top five using head. This reveals the highest CPU consumers, aiding in performance diagnostics by focusing on outliers rather than exhaustive lists.[11]

For tracing process hierarchies, such as parent-child relationships, piping can facilitate recursive inspection. A simplified example is pgrep apache | xargs ps -l, where pgrep extracts PIDs matching "apache" and pipes them to xargs to invoke ps -l (long format) on those PIDs, showing detailed parent IDs (PPID) and command lines for targeted lineage analysis. This integration with pgrep and pkill extends to scripting for automation, like dynamically killing processes based on filtered criteria, which is a staple in sysadmin scripts to maintain system efficiency without full scans.[12]

Implementations

Original AT&T Version

Theps command originated as part of the early Unix development at AT&T Bell Laboratories, with its foundational implementation appearing in the Sixth Edition (1975) and refined in the Seventh Edition (V7) released in 1979.[13][14] Developed alongside the V7 Unix system, it provided a basic mechanism to report the status of active processes by accessing the kernel's process table, offering users a snapshot of running tasks without real-time monitoring capabilities. This version focused on essential process indicia for system administrators in multi-user environments, emphasizing reliability over extensive customization.

In its original form, ps displayed core information including the process ID (PID), terminal identifier (TTY), cumulative CPU time (TIME), and command name (CMD) in a short listing by default, limited to processes associated with the invoking terminal.[14] Early options were minimal, such as -a to include all processes with terminals, -x for processes without terminals, and -l for a long listing that added details like flags (F), state (S), user ID (UID), parent PID (PPID), priority (PRI), nice value (NI), memory size (SZ), and wait channel (WCHAN).[14] A full listing option (-f) was introduced in subsequent AT&T commercial releases, enabling display of command arguments by examining memory or swap space, though defunct (zombie) processes were marked as <defunct> with potentially unreliable data.[15] The command relied on direct kernel memory access via files like /dev/mem, /dev/kmem, and the namelist /unix, without initial support for user-oriented views or filtering by user ID or group, prioritizing raw system-level insights.[14][15]

Technically, the original ps queried the Unix kernel's process table—a data structure tracking all active processes—for its output, using system calls to retrieve states such as running (R), sleeping (S), or waiting (W).[13] This approach, inherited from V7, formed the basis for AT&T's commercial Unix variants like System III (1981) and System V (1983), where it was adapted for broader multi-user systems but remained tied to proprietary kernel interfaces without wide interoperability. Limitations included its dependence on superuser privileges for certain memory accesses (e.g., via alternate core files like /usr/sys/core with -k), lack of standardization beyond AT&T ecosystems, and focus on terminal-bound processes in multi-user setups, making it less suitable for diverse hardware or non-AT&T environments initially.[14][15]

As the cornerstone of AT&T's Unix lineage, the original ps influenced System V Release 4 (SVR4) in 1988, which extended its features with additional options like -e for all processes and -u for user-specific views while preserving the core process table reliance.[16] This legacy extended to proprietary Unix systems such as Solaris, where SVR4-based implementations retained the command's foundational structure for process monitoring. The source code for these early AT&T versions was not publicly released until the 1990s, when AT&T licensed it through initiatives like the UnixWare project, enabling further study and adaptation. This evolution laid groundwork for POSIX standardization, though the original remained distinctly proprietary.[16]

BSD and POSIX Variants

The BSD variants of theps command, as implemented in systems like FreeBSD, NetBSD, and OpenBSD, build upon early Unix designs with enhancements focused on user-friendly output and system-specific features. These implementations emphasize intuitive displays, such as the -aux option, which lists all processes (-a), includes those without controlling terminals (-x), and provides a user-oriented format (-u) showing fields like CPU usage, memory consumption, and the full command line in wide output (-w).[5] In FreeBSD, for example, -u defaults to columns including user, PID, %CPU, %MEM, VSZ, RSS, TTY, STAT, START, and TIME, prioritizing readability for administrators monitoring resource usage.[5] Similar options appear in NetBSD and OpenBSD, where ps -aux produces a comparable overview, though OpenBSD's version omits some FreeBSD-specific extensions for simplicity and security.[17][18]

Apple's macOS employs a hybrid approach, derived from BSD but incorporating POSIX and System V influences for broader compatibility. The ps utility in macOS supports traditional BSD-style options without leading dashes (e.g., ps aux), alongside dashed POSIX variants (e.g., ps -ef), allowing seamless use in scripts across Unix-like environments. This blend ensures the command displays process details like those in pure BSD systems while adhering to standards for portability.[19]

The POSIX and Single UNIX Specification (SUS) define a standardized ps for cross-system consistency, mandating options like -e to list all processes and -f for a full-format output including UID, PID, PPID, C, STIME, TTY, TIME, and CMD.[9] Format specifiers via -o enable custom columns, such as pid, ppid, user, pcpu, vsz, comm, and args, introduced in POSIX.2-1992 to allow flexible, user-defined reports without relying on predefined layouts.[9] SUSv4 (2013), aligning with POSIX.1-2008, extends this with fields for security contexts, including ruser and user for real and effective user IDs, and optional support for labels in multi-level secure environments, enhancing visibility of privilege information.[9] These features are implemented in most Unix-like systems, including BSD derivatives, to ensure predictable behavior in portable applications.

BSD implementations prioritize usability over strict adherence to standards, using dashless options and predefined formats like -u for quick insights, whereas POSIX/SUS emphasizes dashed options and modular -o specifiers for consistent, scriptable output across diverse platforms.[5][9] For instance, BSD ps aux provides an immediate, human-readable summary without needing explicit field selection, contrasting with POSIX's requirement for explicit selectors like -A for all processes. This divergence allows BSD systems to offer enhanced defaults while maintaining partial POSIX compliance through options like -o and -e.[20]

In modern BSD releases, ps supports containerized environments, a key evolution for virtualization. FreeBSD, for example, includes the -J option to filter processes within specific jails—lightweight, kernel-level containers akin to Docker—allowing administrators to monitor isolated workloads like those in OCI-compatible setups via tools such as runj.[5][21] Recent versions (e.g., FreeBSD 14+) extend this to display jail IDs and resource usage, facilitating oversight of containerized applications without external tools.[22] NetBSD and OpenBSD offer analogous capabilities through their ps variants, though with less emphasis on jail-specific flags, relying instead on general process selectors for rumsys or similar isolation mechanisms.[17][18]

procps-ng (Linux) Version

The GNU implementation of theps command, provided by the procps-ng package, has been a standard component of Linux systems since the early 1990s, with its initial release as procps version 0.9 in January 1994.[23] This implementation was originally developed to leverage the /proc filesystem introduced in Linux kernel 1.0, allowing efficient access to process information without requiring special permissions beyond standard file reads.[2] In 2010, procps-ng emerged as an active fork to address stagnation in the original procps codebase, incorporating modern enhancements while maintaining backward compatibility.[24]

A key feature of the GNU ps is its support for both BSD-style options (e.g., ps aux) and POSIX-compliant syntax (e.g., ps -ef), enabling flexible process selection across different environments.[2] It includes GNU-specific extensions such as the -N or --deselect option to negate process selections and --ppid for filtering by parent process ID, which facilitate advanced querying beyond standard POSIX requirements.[2] Additionally, the -f option produces a "forest" format that displays process hierarchies in a tree-like structure, aiding visualization of parent-child relationships.[2] The -n option enables numeric output for user IDs and wait channels, supporting numeric UID sorting when combined with the --sort option.[2]

Deep integration with the Linux /proc filesystem is central to its operation, where ps reads runtime data from directories like /proc/PID/stat and /proc/PID/status to report details such as CPU usage, memory consumption, and command lines.[2] Recent versions include support for displaying control group information, with the cgroups field added in procps-ng 3.3.0 and the cgname field in 3.3.12 (e.g., ps -o pid,cgname), reflecting containerized environments common in modern Linux.[25] Similarly, version 4.0.0 added OOM (Out-of-Memory) score and adjustment fields (oom and oomadj), providing insights into the kernel's memory pressure handling for processes. As of November 2025, the latest stable release is 4.0.4.[25][26]

In contemporary Linux distributions such as Ubuntu, the procps-ng package is installed by default and delivers the ps utility, ensuring broad availability for system administration tasks. Security considerations include kernel-level protections via the hidepid mount option for /proc (introduced in Linux 3.2), which can restrict non-owner users from viewing other processes' details in ps output when mounted with hidepid=2.[27] This feature enhances privacy in multi-user environments without altering the ps tool itself, though ps respects kernel-enforced visibility rules.[2]