Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Public-key cryptography

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Public-key cryptography, or asymmetric cryptography, is the field of cryptographic systems that use pairs of related keys. Each key pair consists of a public key and a corresponding private key.[1][2] Key pairs are generated with cryptographic algorithms based on mathematical problems termed one-way functions. Security of public-key cryptography depends on keeping the private key secret; the public key can be openly distributed without compromising security.[3] There are many kinds of public-key cryptosystems, with different security goals, including digital signature, Diffie–Hellman key exchange, public-key key encapsulation, and public-key encryption.

Public key algorithms are fundamental security primitives in modern cryptosystems, including applications and protocols that offer assurance of the confidentiality and authenticity of electronic communications and data storage. They underpin numerous Internet standards, such as Transport Layer Security (TLS), SSH, S/MIME, and PGP. Compared to symmetric cryptography, public-key cryptography can be too slow for many purposes,[4] so these protocols often combine symmetric cryptography with public-key cryptography in hybrid cryptosystems.

Description

[edit]Before the mid-1970s, all cipher systems used symmetric key algorithms, in which the same cryptographic key is used with the underlying algorithm by both the sender and the recipient, who must both keep it secret. Of necessity, the key in every such system had to be exchanged between the communicating parties in some secure way prior to any use of the system – for instance, via a secure channel. This requirement is never trivial and very rapidly becomes unmanageable as the number of participants increases, or when secure channels are not available, or when (as is sensible cryptographic practice) keys are frequently changed. In particular, if messages are meant to be secure from other users, a separate key is required for each possible pair of users.

By contrast, in a public-key cryptosystem, the public keys can be disseminated widely and openly, and only the corresponding private keys need be kept secret.

The two best-known types of public key cryptography are digital signature and public-key encryption:

- In a digital signature system, a sender can use a private key together with a message to create a signature. Anyone with the corresponding public key can verify whether the signature matches the message, but a forger who does not know the private key cannot find any message/signature pair that will pass verification with the public key.[5][6][7]

For example, a software publisher can create a signature key pair and include the public key in software installed on computers. Later, the publisher can distribute an update to the software signed using the private key, and any computer receiving an update can confirm it is genuine by verifying the signature using the public key. As long as the software publisher keeps the private key secret, even if a forger can distribute malicious updates to computers, they cannot convince the computers that any malicious updates are genuine.

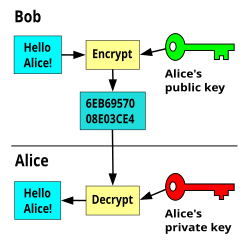

- In a public-key encryption system, anyone with a public key can encrypt a message, yielding a ciphertext, but only those who know the corresponding private key can decrypt the ciphertext to obtain the original message.[8]

For example, a journalist can publish the public key of an encryption key pair on a web site so that sources can send secret messages to the news organization in ciphertext.

Only the journalist who knows the corresponding private key can decrypt the ciphertexts to obtain the sources' messages—an eavesdropper reading email on its way to the journalist cannot decrypt the ciphertexts. However, public-key encryption does not conceal metadata like what computer a source used to send a message, when they sent it, or how long it is.[9][10][11][12] Public-key encryption on its own also does not tell the recipient anything about who sent a message[8]: 283 [13][14]—it just conceals the content of the message.

Applications built on public-key cryptography include authenticating web servers with TLS, digital cash, password-authenticated key agreement, authenticating and concealing email content with OpenPGP or S/MIME, and time-stamping services and non-repudiation protocols.

One important issue is confidence/proof that a particular public key is authentic, i.e. that it is correct and belongs to the person or entity claimed, and has not been tampered with or replaced by some (perhaps malicious) third party. There are several possible approaches, including:

A public key infrastructure (PKI), in which one or more third parties – known as certificate authorities – certify ownership of key pairs. TLS relies upon this. This implies that the PKI system (software, hardware, and management) is trust-able by all involved.

A "web of trust" decentralizes authentication by using individual endorsements of links between a user and the public key belonging to that user. PGP uses this approach, in addition to lookup in the domain name system (DNS). The DKIM system for digitally signing emails also uses this approach.

Hybrid cryptosystems

[edit]Because asymmetric key algorithms are nearly always much more computationally intensive than symmetric ones, it is common to use a public/private asymmetric key-exchange algorithm to encrypt and exchange a symmetric key, which is then used by symmetric-key cryptography to transmit data using the now-shared symmetric key for a symmetric key encryption algorithm. PGP, SSH, and the SSL/TLS family of schemes use this procedure; they are thus called hybrid cryptosystems. The initial asymmetric cryptography-based key exchange to share a server-generated symmetric key from the server to client has the advantage of not requiring that a symmetric key be pre-shared manually, such as on printed paper or discs transported by a courier, while providing the higher data throughput of symmetric key cryptography over asymmetric key cryptography for the remainder of the shared connection.

Weaknesses

[edit]As with all security-related systems, there are various potential weaknesses in public-key cryptography. Aside from poor choice of an asymmetric key algorithm (there are few that are widely regarded as satisfactory) or too short a key length, the chief security risk is that the private key of a pair becomes known. All security of messages, authentication, etc., encrypted with this private key will then be lost. This is commonly mitigated (such as in recent TLS schemes) by using Forward secrecy capable schemes that generate an ephemeral set of keys during the communication which must also be known for the communication to be compromised.

Additionally, with the advent of quantum computing, many asymmetric key algorithms are considered vulnerable to attacks, and new quantum-resistant schemes are being developed to overcome the problem.[15][16]

Beyond algorithmic or key-length weaknesses, some studies have noted risks when private key control is delegated to third parties. Research on Uruguay’s implementation of Public Key Infrastructure under Law 18.600 found that centralized key custody by Trust Service Providers (TSPs) may weaken the principle of private-key secrecy, increasing exposure to man-in-the-middle attacks and raising concerns about legal non-repudiation.[17]

Algorithms

[edit]All public key schemes are in theory susceptible to a "brute-force key search attack".[18] However, such an attack is impractical if the amount of computation needed to succeed – termed the "work factor" by Claude Shannon – is out of reach of all potential attackers. In many cases, the work factor can be increased by simply choosing a longer key. But other algorithms may inherently have much lower work factors, making resistance to a brute-force attack (e.g., from longer keys) irrelevant. Some special and specific algorithms have been developed to aid in attacking some public key encryption algorithms; both RSA and ElGamal encryption have known attacks that are much faster than the brute-force approach.[citation needed] None of these are sufficiently improved to be actually practical, however.

Major weaknesses have been found for several formerly promising asymmetric key algorithms. The "knapsack packing" algorithm was found to be insecure after the development of a new attack.[19] As with all cryptographic functions, public-key implementations may be vulnerable to side-channel attacks that exploit information leakage to simplify the search for a secret key. These are often independent of the algorithm being used. Research is underway to both discover, and to protect against, new attacks.

Alteration of public keys

[edit]Another potential security vulnerability in using asymmetric keys is the possibility of a "man-in-the-middle" attack, in which the communication of public keys is intercepted by a third party (the "man in the middle") and then modified to provide different public keys instead. Encrypted messages and responses must, in all instances, be intercepted, decrypted, and re-encrypted by the attacker using the correct public keys for the different communication segments so as to avoid suspicion.[citation needed]

A communication is said to be insecure where data is transmitted in a manner that allows for interception (also called "sniffing"). These terms refer to reading the sender's private data in its entirety. A communication is particularly unsafe when interceptions can not be prevented or monitored by the sender.[20]

A man-in-the-middle attack can be difficult to implement due to the complexities of modern security protocols. However, the task becomes simpler when a sender is using insecure media such as public networks, the Internet, or wireless communication. In these cases an attacker can compromise the communications infrastructure rather than the data itself. A hypothetical malicious staff member at an Internet service provider (ISP) might find a man-in-the-middle attack relatively straightforward. Capturing the public key would only require searching for the key as it gets sent through the ISP's communications hardware; in properly implemented asymmetric key schemes, this is not a significant risk.[citation needed]

In some advanced man-in-the-middle attacks, one side of the communication will see the original data while the other will receive a malicious variant. Asymmetric man-in-the-middle attacks can prevent users from realizing their connection is compromised. This remains so even when one user's data is known to be compromised because the data appears fine to the other user. This can lead to confusing disagreements between users such as "it must be on your end!" when neither user is at fault. Hence, man-in-the-middle attacks are only fully preventable when the communications infrastructure is physically controlled by one or both parties; such as via a wired route inside the sender's own building. In summation, public keys are easier to alter when the communications hardware used by a sender is controlled by an attacker.[21][22][23]

Public key infrastructure

[edit]One approach to prevent such attacks involves the use of a public key infrastructure (PKI); a set of roles, policies, and procedures needed to create, manage, distribute, use, store and revoke digital certificates and manage public-key encryption. However, this has potential weaknesses.

For example, the certificate authority issuing the certificate must be trusted by all participating parties to have properly checked the identity of the key-holder, to have ensured the correctness of the public key when it issues a certificate, to be secure from computer piracy, and to have made arrangements with all participants to check all their certificates before protected communications can begin. Web browsers, for instance, are supplied with a long list of "self-signed identity certificates" from PKI providers – these are used to check the bona fides of the certificate authority and then, in a second step, the certificates of potential communicators. An attacker who could subvert one of those certificate authorities into issuing a certificate for a bogus public key could then mount a "man-in-the-middle" attack as easily as if the certificate scheme were not used at all. An attacker who penetrates an authority's servers and obtains its store of certificates and keys (public and private) would be able to spoof, masquerade, decrypt, and forge transactions without limit, assuming that they were able to place themselves in the communication stream.

Despite its theoretical and potential problems, Public key infrastructure is widely used. Examples include TLS and its predecessor SSL, which are commonly used to provide security for web browser transactions (for example, most websites utilize TLS for HTTPS).

Aside from the resistance to attack of a particular key pair, the security of the certification hierarchy must be considered when deploying public key systems. Some certificate authority – usually a purpose-built program running on a server computer – vouches for the identities assigned to specific private keys by producing a digital certificate. Public key digital certificates are typically valid for several years at a time, so the associated private keys must be held securely over that time. When a private key used for certificate creation higher in the PKI server hierarchy is compromised, or accidentally disclosed, then a "man-in-the-middle attack" is possible, making any subordinate certificate wholly insecure.

Unencrypted metadata

[edit]Most of the available public-key encryption software does not conceal metadata in the message header, which might include the identities of the sender and recipient, the sending date, subject field, and the software they use etc. Rather, only the body of the message is concealed and can only be decrypted with the private key of the intended recipient. This means that a third party could construct quite a detailed model of participants in a communication network, along with the subjects being discussed, even if the message body itself is hidden.

However, there has been a recent demonstration of messaging with encrypted headers, which obscures the identities of the sender and recipient, and significantly reduces the available metadata to a third party.[24] The concept is based around an open repository containing separately encrypted metadata blocks and encrypted messages. Only the intended recipient is able to decrypt the metadata block, and having done so they can identify and download their messages and decrypt them. Such a messaging system is at present in an experimental phase and not yet deployed. Scaling this method would reveal to the third party only the inbox server being used by the recipient and the timestamp of sending and receiving. The server could be shared by thousands of users, making social network modelling much more challenging.

History

[edit]During the early history of cryptography, two parties would rely upon a key that they would exchange by means of a secure, but non-cryptographic, method such as a face-to-face meeting, or a trusted courier. This key, which both parties must then keep absolutely secret, could then be used to exchange encrypted messages. A number of significant practical difficulties arise with this approach to distributing keys.

Anticipation

[edit]In his 1874 book The Principles of Science, William Stanley Jevons wrote:[25]

Can the reader say what two numbers multiplied together will produce the number 8616460799?[26] I think it unlikely that anyone but myself will ever know.[25]

Here he described the relationship of one-way functions to cryptography, and went on to discuss specifically the factorization problem used to create a trapdoor function. In July 1996, mathematician Solomon W. Golomb said: "Jevons anticipated a key feature of the RSA Algorithm for public key cryptography, although he certainly did not invent the concept of public key cryptography."[27]

Classified discovery

[edit]In 1970, James H. Ellis, a British cryptographer at the UK Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), conceived of the possibility of "non-secret encryption", (now called public key cryptography), but could see no way to implement it.[28][29]

In 1973, his colleague Clifford Cocks implemented what has become known as the RSA encryption algorithm, giving a practical method of "non-secret encryption", and in 1974 another GCHQ mathematician and cryptographer, Malcolm J. Williamson, developed what is now known as Diffie–Hellman key exchange. The scheme was also passed to the US's National Security Agency.[30] Both organisations had a military focus and only limited computing power was available in any case; the potential of public key cryptography remained unrealised by either organization. According to Ralph Benjamin:

I judged it most important for military use ... if you can share your key rapidly and electronically, you have a major advantage over your opponent. Only at the end of the evolution from Berners-Lee designing an open internet architecture for CERN, its adaptation and adoption for the Arpanet ... did public key cryptography realise its full potential.[30]

These discoveries were not publicly acknowledged until the research was declassified by the British government in 1997.[31]

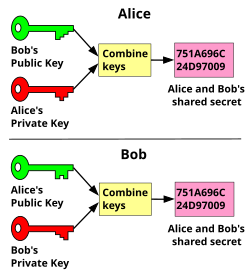

Public discovery

[edit]In 1976, an asymmetric key cryptosystem was published by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman who, influenced by Ralph Merkle's work on public key distribution, disclosed a method of public key agreement. This method of key exchange, which uses exponentiation in a finite field, came to be known as Diffie–Hellman key exchange.[32] This was the first published practical method for establishing a shared secret-key over an authenticated (but not confidential) communications channel without using a prior shared secret. Merkle's "public key-agreement technique" became known as Merkle's Puzzles, and was invented in 1974 and only published in 1978. This makes asymmetric encryption a rather new field in cryptography although cryptography itself dates back more than 2,000 years.[33]

In 1977, a generalization of Cocks's scheme was independently invented by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir and Leonard Adleman, all then at MIT. The latter authors published their work in 1978 in Martin Gardner's Scientific American column, and the algorithm came to be known as RSA, from their initials.[34] RSA uses exponentiation modulo a product of two very large primes, to encrypt and decrypt, performing both public key encryption and public key digital signatures. Its security is connected to the extreme difficulty of factoring large integers, a problem for which there is no known efficient general technique. A description of the algorithm was published in the Mathematical Games column in the August 1977 issue of Scientific American.[35]

Since the 1970s, a large number and variety of encryption, digital signature, key agreement, and other techniques have been developed, including the Rabin signature, ElGamal encryption, DSA and ECC.

Examples

[edit]Examples of well-regarded asymmetric key techniques for varied purposes include:

- Diffie–Hellman key exchange protocol

- DSS (Digital Signature Standard), which incorporates the Digital Signature Algorithm

- ElGamal

- Elliptic-curve cryptography

- Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA)

- Elliptic-curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDH)

- Ed25519 and Ed448 (EdDSA)

- X25519 and X448 (ECDH/EdDH)

- Various password-authenticated key agreement techniques

- Paillier cryptosystem

- RSA encryption algorithm (PKCS#1)

- Cramer–Shoup cryptosystem

- YAK authenticated key agreement protocol

Examples of asymmetric key algorithms not yet widely adopted include:

- NTRUEncrypt cryptosystem

- Kyber

- McEliece cryptosystem

Examples of notable – yet insecure – asymmetric key algorithms include:

Examples of protocols using asymmetric key algorithms include:

- S/MIME

- GPG, an implementation of OpenPGP, and an Internet Standard

- EMV, EMV Certificate Authority

- IPsec

- PGP

- ZRTP, a secure VoIP protocol

- Transport Layer Security standardized by IETF and its predecessor Secure Socket Layer

- SILC

- SSH

- Bitcoin

- Off-the-Record Messaging

See also

[edit]- Books on cryptography

- GNU Privacy Guard

- Identity-based encryption (IBE)

- Key escrow

- Key-agreement protocol

- PGP word list

- Post-quantum cryptography

- Pretty Good Privacy

- Pseudonym

- Public key fingerprint

- Public key infrastructure (PKI)

- Quantum computing

- Quantum cryptography

- Secure Shell (SSH)

- Symmetric-key algorithm

- Threshold cryptosystem

- Web of trust

References

[edit]- ^ R. Shirey (August 2007). Internet Security Glossary, Version 2. Network Working Group. doi:10.17487/RFC4949. RFC 4949. Informational.

- ^ Bernstein, Daniel J.; Lange, Tanja (14 September 2017). "Post-quantum cryptography". Nature. 549 (7671): 188–194. Bibcode:2017Natur.549..188B. doi:10.1038/nature23461. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28905891. S2CID 4446249.

- ^ Stallings, William (3 May 1990). Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice. Prentice Hall. p. 165. ISBN 9780138690175.

- ^ Alvarez, Rafael; Caballero-Gil, Cándido; Santonja, Juan; Zamora, Antonio (27 June 2017). "Algorithms for Lightweight Key Exchange". Sensors. 17 (7): 1517. doi:10.3390/s17071517. ISSN 1424-8220. PMC 5551094. PMID 28654006.

- ^ Menezes, Alfred J.; van Oorschot, Paul C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (October 1996). "Chapter 8: Public-key encryption". Handbook of Applied Cryptography (PDF). CRC Press. pp. 425–488. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Bernstein, Daniel J. (1 May 2008). "Protecting communications against forgery". Algorithmic Number Theory (PDF). Vol. 44. MSRI Publications. §5: Public-key signatures, pp. 543–545. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Bellare, Mihir; Goldwasser, Shafi (July 2008). "Chapter 10: Digital signatures". Lecture Notes on Cryptography (PDF). p. 168. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b Menezes, Alfred J.; van Oorschot, Paul C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (October 1996). "8: Public-key encryption". Handbook of Applied Cryptography (PDF). CRC Press. pp. 283–319. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Danezis, George; Diaz, Claudia; Syverson, Paul (2010). "Chapter 13: Anonymous Communication". In Rosenberg, Burton (ed.). Handbook of Financial Cryptography and Security (PDF). Chapman & Hall/CRC. pp. 341–390. ISBN 978-1420059816.

Since PGP, beyond compressing the messages, does not make any further attempts to hide their size, it is trivial to follow a message in the network just by observing its length.

- ^ Rackoff, Charles; Simon, Daniel R. (1993). "Cryptographic defense against traffic analysis". Proceedings of the twenty-fifth annual ACM symposium on Theory of Computing. STOC '93: ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 672–681. doi:10.1145/167088.167260.

Now, certain types of information cannot reasonably be assumed to be concealed. For instance, an upper bound on the total volume of a party's sent or received communication (of any sort) is obtainable by anyone with the resources to examine all possible physical communication channels available to that party.

- ^ Karger, Paul A. (May 1977). "11: Limitations of End-to-End Encryption". Non-Discretionary Access Control for Decentralized Computing Systems (S.M. thesis). Laboratory for Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. hdl:1721.1/149471.

The scenario just described would seem to be secure, because all data is encrypted before being passed to the communications processors. However, certain control information must be passed in cleartext from the host to the communications processor to allow the network to function. This control information consists of the destination address for the packet, the length of the packet, and the time between successive packet transmissions.

- ^ Chaum, David L. (February 1981). Rivest, R. (ed.). "Untraceable Electronic Mail, Return Addresses, and Digital Pseudonyms". Communications of the ACM. 24 (2). Association for Computing Machinery.

Recently, some new solutions to the "key distribution problem" (the problem of providing each communicant with a secret key) have been suggested, under the name of public key cryptography. Another cryptographic problem, the "traffic analysis problem" (the problem of keeping confidential who converses with whom, and when they converse), will become increasingly important with the growth of electronic mail.

- ^ Davis, Don (2001). "Defective Sign & Encrypt in S/MIME, PKCS#7, MOSS, PEM, PGP, and XML". Proceedings of the 2001 USENIX Annual Technical Conference. USENIX. pp. 65–78.

Why is naïve Sign & Encrypt insecure? Most simply, S&E is vulnerable to "surreptitious forwarding:" Alice signs & encrypts for Bob's eyes, but Bob re-encrypts Alice's signed message for Charlie to see. In the end, Charlie believes Alice wrote to him directly, and can't detect Bob's subterfuge.

- ^ An, Jee Hea (12 September 2001). Authenticated Encryption in the Public-Key Setting: Security Notions and Analyses (Technical report). IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2001/079. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ Escribano Pablos, José Ignacio; González Vasco, María Isabel (April 2023). "Secure post-quantum group key exchange: Implementing a solution based on Kyber". IET Communications. 17 (6): 758–773. doi:10.1049/cmu2.12561. hdl:10016/37141. ISSN 1751-8628. S2CID 255650398.

- ^ Stohrer, Christian; Lugrin, Thomas (2023), Mulder, Valentin; Mermoud, Alain; Lenders, Vincent; Tellenbach, Bernhard (eds.), "Asymmetric Encryption", Trends in Data Protection and Encryption Technologies, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 11–14, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-33386-6_3, ISBN 978-3-031-33386-6

- ^ Sabiguero, Ariel; Vicente, Alfonso; Esnal, Gonzalo (November 2024). "Let There Be Trust". 2024 IEEE URUCON. doi:10.1109/URUCON63440.2024.10850093.

- ^ Paar, Christof; Pelzl, Jan; Preneel, Bart (2010). Understanding Cryptography: A Textbook for Students and Practitioners. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-04100-6.

- ^ Shamir, Adi (November 1982). "A polynomial time algorithm for breaking the basic Merkle-Hellman cryptosystem". 23rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (SFCS 1982). pp. 145–152. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1982.5.

- ^ Tunggal, Abi (20 February 2020). "What Is a Man-in-the-Middle Attack and How Can It Be Prevented – What is the difference between a man-in-the-middle attack and sniffing?". UpGuard. Retrieved 26 June 2020.[self-published source?]

- ^ Tunggal, Abi (20 February 2020). "What Is a Man-in-the-Middle Attack and How Can It Be Prevented - Where do man-in-the-middle attacks happen?". UpGuard. Retrieved 26 June 2020.[self-published source?]

- ^ martin (30 January 2013). "China, GitHub and the man-in-the-middle". GreatFire. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2015.[self-published source?]

- ^ percy (4 September 2014). "Authorities launch man-in-the-middle attack on Google". GreatFire. Retrieved 26 June 2020.[self-published source?]

- ^ Bjorgvinsdottir, Hanna; Bentley, Phil (24 June 2021). "Warp2: A Method of Email and Messaging with Encrypted Addressing and Headers". arXiv:1411.6409 [cs.CR].

- ^ a b Jevons, W.S. (1874). The Principles of Science: A Treatise on Logic and Scientific Method. Macmillan & Co. p. 141. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Weisstein, E.W. (2024). "Jevons' Number". MathWorld. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Golob, Solomon W. (1996). "On Factoring Jevons' Number". Cryptologia. 20 (3): 243. doi:10.1080/0161-119691884933. S2CID 205488749.

- ^ Ellis, James H. (January 1970). "The Possibility of Secure Non-secret Digital Encryption" (PDF). CryptoCellar. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Sawer, Patrick (11 March 2016). "The unsung genius who secured Britain's computer defences and paved the way for safe online shopping". The Telegraph.

- ^ a b Espiner, Tom (26 October 2010). "GCHQ pioneers on birth of public key crypto". ZDNet.

- ^ Singh, Simon (1999). The Code Book. Doubleday. pp. 279–292.

- ^ Diffie, Whitfield; Hellman, Martin E. (November 1976). "New Directions in Cryptography" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 22 (6): 644–654. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.37.9720. doi:10.1109/TIT.1976.1055638. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Asymmetric encryption". IONOS Digitalguide. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Rivest, R.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. (February 1978). "A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 21 (2): 120–126. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.607.2677. doi:10.1145/359340.359342. S2CID 2873616. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Robinson, Sara (June 2003). "Still Guarding Secrets after Years of Attacks, RSA Earns Accolades for its Founders" (PDF). SIAM News. 36 (5).

Sources

[edit]- Hirsch, Frederick J. "SSL/TLS Strong Encryption: An Introduction". Apache HTTP Server. Retrieved 17 April 2013.. The first two sections contain a very good introduction to public-key cryptography.

- Ferguson, Niels; Schneier, Bruce (2003). Practical Cryptography. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-22357-3.

- Katz, Jon; Lindell, Y. (2007). Introduction to Modern Cryptography. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-58488-551-1.

- Menezes, A. J.; van Oorschot, P. C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (1997). Handbook of Applied Cryptography. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8493-8523-7.

- IEEE 1363: Standard Specifications for Public-Key Cryptography

- Christof Paar, Jan Pelzl, "Introduction to Public-Key Cryptography", Chapter 6 of "Understanding Cryptography, A Textbook for Students and Practitioners". (companion web site contains online cryptography course that covers public-key cryptography), Springer, 2009.

- Salomaa, Arto (1996). Public-Key Cryptography (2 ed.). Berlin: Springer. 275. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-03269-5. ISBN 978-3-662-03269-5. S2CID 24751345.

External links

[edit]- Oral history interview with Martin Hellman, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Leading cryptography scholar Martin Hellman discusses the circumstances and fundamental insights of his invention of public key cryptography with collaborators Whitfield Diffie and Ralph Merkle at Stanford University in the mid-1970s.

- An account of how GCHQ kept their invention of PKE secret until 1997

Public-key cryptography

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Public-key cryptography, also known as asymmetric cryptography, is a cryptographic system that utilizes a pair of related keys—a public key and a private key—to secure communications and data. Unlike symmetric cryptography, which relies on a single shared secret key for both encryption and decryption, public-key cryptography employs distinct keys for these operations: the public key is freely distributed and used for encryption or signature verification, while the private key is kept secret and used for decryption or signature generation. This asymmetry ensures that the private key cannot be feasibly derived from the public key, providing a foundation for secure interactions without the need for prior secret key exchange.[6][7] The core principles of public-key cryptography revolve around achieving key security objectives through the key pair mechanism. Confidentiality is ensured by encrypting messages with the recipient's public key, allowing only the private key holder to decrypt and access the plaintext. Integrity and authentication are supported via digital signatures, where the sender signs the message with their private key, enabling the recipient to verify authenticity and unaltered content using the sender's public key. Non-repudiation is also provided, as a valid signature binds the sender irrevocably to the message, preventing denial of origin. These principles rely on the computational difficulty of inverting certain mathematical functions without the private key, often referred to as trapdoor one-way functions.[6][7] Developed in the 1970s to address the key distribution challenges inherent in symmetric systems—where securely sharing a single key over insecure channels is problematic—public-key cryptography revolutionized secure communication by enabling key exchange via public directories. In a basic workflow, the sender obtains the recipient's public key, encrypts the plaintext message to produce ciphertext, and transmits it over an open channel; the recipient then applies their private key to decrypt the message, ensuring only they can recover the original content. This approach underpins modern secure protocols without requiring trusted intermediaries for initial key setup.[7][6]Key Components

Public and private keys form the core of public-key cryptography, generated as a mathematically related pair through specialized algorithms. The public key is designed for open distribution to enable secure communications with multiple parties, while the private key must be kept confidential by its owner to maintain system security. This asymmetry allows anyone to encrypt messages or verify signatures using the public key, but only the private key holder can decrypt or produce valid signatures.[8][9] Certificates play a crucial role in associating public keys with specific identities, preventing impersonation and enabling trust in distributed systems. Issued by trusted certificate authorities (CAs), a public key certificate contains the public key, the holder's identity details, and a digital signature from the CA verifying the binding. This structure, as defined in standards like X.509, allows verification of key authenticity without direct knowledge of the private key.[10][11] Key rings provide a practical mechanism for managing multiple keys, particularly in decentralized environments. In systems like Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), a public key ring stores the public keys of other users for encryption and verification, while a separate private key ring holds the user's own private keys, protected by passphrases. These structures facilitate efficient key lookup and usage without compromising secrecy.[12][13] Different public-key algorithms exhibit varying properties in terms of key size, computational demands, and achievable security levels, influencing their suitability for applications. The table below compares representative algorithms for equivalent security strength, based on NIST guidelines for key lengths providing at least 128 bits of security against classical attacks. Computational costs are relative, with elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) generally requiring fewer resources due to smaller keys and optimized operations compared to RSA or DSA.[3][14]| Algorithm | Key Size (bits) | Relative Computation Cost | Security Level (bits) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSA | 3072 | High (modular exponentiation intensive) | 128 |

| ECC | 256 | Low (efficient scalar multiplication) | 128 |

| DSA | 3072 (modulus) | Medium (discrete log operations) | 128 |

Mathematical Foundations

Asymmetric Encryption Basics

Asymmetric encryption, a cornerstone of public-key cryptography, employs a pair of mathematically related keys: a publicly available encryption key that anyone can use to encipher a message, and a secret private key held only by the intended recipient for decryption. This approach allows secure communication over insecure channels without the need for prior secret key exchange, fundamentally differing from symmetric methods by decoupling encryption and decryption processes. The underlying mathematics is rooted in modular arithmetic, where computations are confined to residues modulo a large composite integer , enabling efficient operations while obscuring the original plaintext without the private key. At the heart of asymmetric encryption lie one-way functions, which are algorithms or mathematical operations that are straightforward and efficient to compute in the forward direction—for instance, transforming an input to an output —but computationally infeasible to reverse, meaning finding given requires prohibitive resources unless augmented by a hidden "trapdoor" parameter known only to the key holder. These functions provide the asymmetry: the public key enables easy forward computation for encryption, while inversion demands the private key's trapdoor information, rendering decryption secure against adversaries. A basic representation of the encryption process uses modular exponentiation: the ciphertext is generated as , where is the plaintext message, is the public exponent component of the public key, and is the modulus. Decryption reverses this via the private exponent , yielding , with the relationship between and tied to the structure of . The security of asymmetric encryption schemes relies on well-established computational hardness assumptions, such as the integer factorization problem, where decomposing a large composite (with and being large primes) into its prime factors is believed to be intractable for sufficiently large values using current algorithms and computing power.Trapdoor One-Way Functions

Trapdoor one-way functions form the foundational mathematical primitive enabling public-key cryptography by providing a mechanism for reversible computation that is computationally feasible only with privileged information. Introduced by Diffie and Hellman, these functions are defined such that forward computation is efficient for anyone, but inversion—recovering the input from the output—is computationally intractable without a secret "trapdoor" parameter, which serves as the private key.[1] With the trapdoor, inversion becomes efficient, allowing authorized parties to decrypt or verify messages while maintaining security against adversaries. This asymmetry underpins the feasibility of public-key systems, where the public key enables easy forward evaluation, but the private key (trapdoor) is required for reversal. Trapdoor functions are typically categorized into permutation-based and function-based types, depending on whether they preserve one-to-one mappings. Permutation-based trapdoor functions, such as those underlying the RSA cryptosystem, involve bijective mappings that are easy to compute forward but hard to invert without knowledge of the trapdoor, often relying on the difficulty of factoring large composite numbers.[4] For instance, in RSA, the public operation raises a message to a power modulo a composite modulus , while inversion uses the private exponent derived from the prime factors and . In contrast, function-based examples like the Rabin cryptosystem employ quadratic residues modulo , where forward computation squares the input modulo , and inversion requires extracting square roots, which is feasible only with the factorization of .[17] These examples illustrate how trapdoor functions can be constructed from number-theoretic problems, ensuring that the public key reveals no information about the inversion process. The inversion process in trapdoor functions can be formally expressed as recovering the original message from the ciphertext using the private key: m = \text{private_key}(c) This operation leverages the secret trapdoor, such as the prime factors in RSA or Rabin, to efficiently compute the inverse without solving the underlying hard problem directly.[4][17] The security of trapdoor one-way functions is established through provable reductions to well-studied hard problems in computational number theory, ensuring that breaking the function is at least as difficult as solving these problems. For permutation-based schemes like RSA and Rabin, security reduces to the integer factorization problem: an adversary who can invert the function efficiently could factor the modulus , a task believed to be intractable for large semiprimes on classical computers.[4][17] Similarly, other trapdoor constructions, such as those based on the discrete logarithm problem in elliptic curves or finite fields, reduce inversion to computing discrete logarithms, providing rigorous guarantees that the system's hardness inherits from these foundational assumptions. This reductionist approach allows cryptographers to analyze and trust public-key schemes by linking their security to long-standing open problems.Core Operations

Key Generation and Distribution

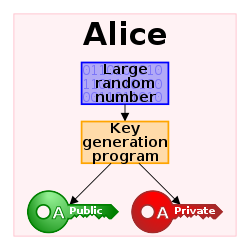

In public-key cryptography, key generation produces a mathematically linked pair consisting of a public key, which can be freely shared, and a private key, which must remain secret. Methods vary by algorithm; for systems like RSA based on integer factorization, this generally involves selecting large, randomly chosen prime numbers as foundational parameters, computing a modulus from their product, and deriving public and private exponents that enable asymmetric operations based on the underlying trapdoor one-way function.[18] In general, the process uses high-entropy random bits from approved sources to select parameters suited to the computational hard problem of the algorithm (e.g., elliptic curve parameters for ECC), and must occur within a secure environment, often using approved cryptographic modules to ensure the keys meet the required security strength.[19] High entropy is essential during key generation to produce unpredictable values, preventing attackers from guessing or brute-forcing the private key from the public one. Random bit strings are sourced from approved random bit generators (RBGs), such as those compliant with NIST standards, which must provide at least as many bits of entropy as the target security level—for instance, at least 256 bits for 128-bit security.[19] Insufficient entropy, often from flawed or predictable sources like low-variability system timers, can render keys vulnerable; a notable example is the 2006-2008 Debian OpenSSL vulnerability (CVE-2008-0166), where a packaging change reduced the random pool to a single PID value, generating only about 15,000 possible SSH keys and enabling widespread compromises.[20] Secure distribution focuses on disseminating the public key while protecting the private key's secrecy. Methods include direct exchange through trusted channels like in-person handoff or encrypted email, publication in public directories or key servers for open retrieval, or establishment via an initial secure channel to bootstrap trust.[21] To mitigate risks like man-in-the-middle attacks, public keys are often accompanied by digital signatures for validation, confirming their authenticity without delving into signature mechanics. Private keys are never distributed and must be generated and stored with protections against extraction, such as hardware security modules. Common pitfalls in distribution, such as unverified public keys, can undermine the system, emphasizing the need for integrity checks during sharing.[19]Encryption and Decryption Processes

In public-key cryptography, the encryption process begins with preparing the plaintext message for secure transmission using methods specific to the algorithm. The message is first converted into a numerical representation and padded using a scheme such as Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding (OAEP) to achieve a length compatible with the key size, prevent attacks like chosen-ciphertext vulnerabilities, and randomize the input for semantic security.[22] In the RSA algorithm, for example, the padded message , treated as an integer less than the modulus , is then encrypted by raising it to the power of the public exponent modulo , yielding the ciphertext .[4] Other schemes, such as ElGamal, employ different operations based on discrete logarithms. This operation ensures that only the corresponding private key can efficiently reverse it, leveraging the trapdoor property of the underlying one-way function.[4] Decryption reverses this process using the private key. In RSA, the recipient applies the private exponent to the ciphertext, computing , which recovers the padded message.[4] The padding is then removed, with built-in integrity checks—such as hash verification in OAEP—to detect and handle errors like invalid padding or tampering, rejecting the decryption if inconsistencies arise.[22] This step ensures the original message is accurately restored only by the legitimate holder of the private key, maintaining confidentiality.[22] Public-key encryption typically processes messages in fixed-size blocks limited by algorithm parameters, such as the modulus in RSA (typically 2048 to 4096 bits as of 2025), unlike many symmetric stream ciphers that handle arbitrary lengths continuously.[4] This imposes a per-block size restriction, often requiring messages to be segmented or, for larger data, combined with symmetric methods in hybrid systems to encrypt bulk content efficiently. Performance-wise, public-key operations incur significant computational overhead due to large-integer arithmetic, which scales cubically with the parameter size and requires far more resources—often thousands of times slower—than symmetric counterparts for equivalent security levels.[4] For instance, encrypting a 200-digit block with RSA on general-purpose hardware in the 1970s took seconds to minutes, highlighting the need for optimization techniques like exponentiation by squaring.[4] This overhead limits direct use for high-volume data, favoring hybrid approaches where public-key methods secure symmetric keys.Digital Signature Mechanisms

Digital signature mechanisms in public-key cryptography provide a means to verify the authenticity and integrity of a message, ensuring that it originated from a specific signer and has not been altered. Introduced conceptually by Diffie and Hellman in 1976, these mechanisms rely on asymmetric key pairs where the private key is used for signing and the public key for verification, leveraging the computational infeasibility of deriving the private key from the public one.[1] This approach allows anyone to verify the signature without needing to share secret keys securely. To create a digital signature, the signer first applies a collision-resistant hash function to the message, producing a fixed-size digest that represents the message's content. The signer then applies their private key to this digest, effectively "encrypting" it to generate the signature. For instance, in the RSA algorithm proposed by Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman in 1978, the signature is computed as , where is the hash of the message, is the private exponent, and is the modulus derived from the product of two large primes.[4] This process ensures that only the holder of the private key can produce a valid signature, as the operation exploits the trapdoor one-way function inherent in the public-key system. For longer messages, hashing is essential to reduce the input to a manageable size, preventing the need to sign each block individually while maintaining security.[23] Other schemes, such as DSA or ECDSA, use different signing operations based on their mathematical foundations. Verification involves the recipient recomputing the hash of the received message and using the signer's public key to "decrypt" the signature, yielding the original digest. The verifier then compares this decrypted value with the newly computed hash; if they match, the signature is valid, confirming both the message's integrity and the signer's identity. In RSA terms, this check is performed by computing , where is the public exponent, and ensuring equals the hash of the message.[4] The use of strong hash functions is critical here, as their collision resistance property makes it computationally infeasible for an attacker to find two different messages with the same hash, thereby preventing forgery of signatures on altered content.[24] A key property of digital signatures is non-repudiation, which binds the signer irrevocably to the message since only their private key could have produced the valid signature, and the public key allows third-party verification without the signer's involvement.[1] This feature underpins applications such as secure email protocols and software distribution, where verifiable authenticity is paramount.[23]Applications and Schemes

Secure Data Transmission

Public-key cryptography plays a pivotal role in secure data transmission by enabling the establishment of encrypted channels over open networks without requiring pre-shared secrets between parties. This addresses the key distribution problem inherent in symmetric cryptography, allowing communicators to securely exchange information even in untrusted environments like the internet. By leveraging asymmetric key pairs, it ensures confidentiality, as data encrypted with a public key can only be decrypted by the corresponding private key held by the intended recipient.[1] In protocols such as Transport Layer Security (TLS), public-key cryptography facilitates key exchange during the initial handshake to derive symmetric session keys for bulk data encryption. For instance, TLS 1.3 mandates the use of ephemeral Diffie-Hellman (DHE) or elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDHE) key exchanges, where parties generate temporary public values to compute a shared secret, providing forward secrecy to protect past sessions against future key compromises. This mechanism authenticates the exchange via digital signatures and encrypts subsequent handshake messages, ensuring secure transmission of application data thereafter.[25][25] For email encryption, standards like OpenPGP and S/MIME rely on public-key cryptography to protect message confidentiality. OpenPGP employs a hybrid approach where a randomly generated symmetric session key encrypts the email content, and that session key is then encrypted using the recipient's public key (e.g., via RSA or ElGamal) before transmission.[13] Similarly, S/MIME uses the Cryptographic Message Syntax (CMS) to wrap a content-encryption key with the recipient's public key through algorithms like RSA or ECDH, supporting enveloped data structures for secure delivery.[26][26] In file sharing scenarios, public-key cryptography enables secure uploads and downloads by allowing senders to encrypt files with the recipient's public key prior to transmission, preventing interception on public networks. OpenPGP implements this by applying the same hybrid encryption process to files as to messages, where symmetric encryption handles the data and public-key encryption secures the session key, ensuring end-to-end confidentiality without shared infrastructure.[13] This approach integrates with symmetric methods for performance, as explored in hybrid systems.[13]Authentication and Non-Repudiation

Public-key cryptography enables authentication by allowing parties to verify the identity of a communicator through the use of digital signatures, which demonstrate possession of a corresponding private key without revealing it.[27] In this context, authentication confirms that the entity claiming an identity is genuine, while non-repudiation ensures that a signer cannot later deny having performed a signing operation, providing evidentiary value in disputes.[4] These properties rely on the asymmetry of key pairs, where the private key signs data and the public key verifies it, binding actions to specific identities.[28] Challenge-response authentication protocols leverage digital signatures to prove private key possession securely. In such protocols, a verifier sends a random challenge—a nonce or timestamped value—to the claimant, who then signs it using their private key and returns the signature along with the challenge.[27] The verifier checks the signature against the claimant's public key; successful verification confirms the claimant controls the private key, as forging the signature would require solving the underlying hard problem, such as integer factorization in RSA.[27] This method resists replay attacks when fresh challenges are used and is specified in standards like FIPS 196 for entity authentication in computer systems.[27] Non-repudiation in public-key systems is achieved through timestamped digital signatures that bind a signer's identity to a document or action, making denial infeasible due to the cryptographic uniqueness of the signature. A signer applies their private key to hash the document and a trusted timestamp, producing a verifiable artifact that third parties can validate with the public key.[28] This ensures the signature was created after the timestamp and before any revocation, providing legal evidentiary weight, as outlined in digital signature standards like DSS.[28] The RSA algorithm, introduced in 1977, formalized this capability by enabling signatures that are computationally infeasible to forge without the private key.[4] Another prominent application is in blockchain and cryptocurrency systems, where users generate public-private key pairs to create wallet addresses from public keys and sign transactions with private keys; verifiers use the public key to confirm authenticity and prevent unauthorized spending, ensuring non-repudiation across distributed networks.[29] Certificate-based authentication extends these mechanisms by linking public keys to real-world identities via X.509 certificates issued by trusted authorities. Each certificate contains the subject's public key, identity attributes (e.g., name or email), and a signature from the issuing certification authority, forming a chain of trust from a root authority.[30] During authentication, the verifier validates the certificate chain, checks revocation status via certificate revocation lists, and uses the bound public key to confirm signatures, ensuring the key belongs to the claimed entity.[30] This approach, profiled in RFC 5280, supports scalable identity verification in distributed systems.[30] In software updates, public-key cryptography facilitates code signing, where developers sign binaries with their private key to assure users of authenticity and integrity, preventing tampering during distribution.[31] For instance, operating systems like Windows verify these signatures before installation, using the associated public key or certificate to block unsigned or altered code.[31] Similarly, in legal documents, electronic signatures employ public-key digital signatures to provide non-repudiation, as seen in frameworks like the U.S. ESIGN Act, which recognizes signatures verifiable via public keys as binding equivalents to handwritten ones.[32] This ensures contracts or approvals cannot be repudiated, with timestamps adding proof of creation time.[32]Hybrid Systems

Combining with Symmetric Cryptography

Public-key cryptography is frequently combined with symmetric cryptography in hybrid cryptosystems to optimize security and performance. Asymmetric methods handle initial key establishment or exchange securely over public channels, deriving a shared symmetric key without prior secrets, while symmetric algorithms then encrypt and decrypt the bulk of the data due to their greater speed and efficiency for large volumes. This hybrid model addresses the computational intensity of public-key operations, which are impractical for direct encryption of extensive payloads, and enhances overall system resilience.[3]Protocol Examples

Key examples of hybrid systems include TLS, where public-key-based key exchanges like ECDHE derive session keys for symmetric ciphers such as AES, securing web communications.[25] In email and file encryption via OpenPGP, a symmetric key encrypts the content, which is then wrapped with the recipient's public key for secure delivery.[13] Similarly, Internet Protocol Security (IPsec) uses Internet Key Exchange (IKE) with Diffie-Hellman to establish symmetric keys for VPN tunnels, combining authentication via digital signatures with efficient data protection.[3]Hybrid Systems

Combining with Symmetric Cryptography

Public-key cryptography, while enabling secure key distribution without prior shared secrets, is computationally intensive and significantly slower for encrypting large volumes of data compared to symmetric cryptography. Symmetric algorithms, such as AES, excel at efficiently processing bulk data due to their simpler operations, but they require a secure channel for key exchange to prevent interception. This disparity in performance—where public-key methods can be up to 1,000 times slower than symmetric ones for equivalent security levels—necessitates a hybrid approach to leverage the strengths of both paradigms.[33][34] In hybrid systems, public-key cryptography facilitates the secure exchange of a temporary symmetric session key, which is then used to encrypt the actual payload. The standard pattern involves the sender generating a random symmetric key, applying it to encrypt the message via a symmetric algorithm, and subsequently encrypting that symmetric key using the recipient's public key before transmission. Upon receipt, the recipient decrypts the symmetric key with their private key and uses it to decrypt the message. This method ensures confidentiality without the overhead of applying public-key operations to the entire data stream.[35][36] The efficiency gains from this integration are substantial; for instance, hybrid encryption achieves approximately 1,000-fold speedup in bulk data processing relative to pure public-key encryption, making it practical for real-world applications like secure file transfers or streaming. Standards such as Hybrid Public Key Encryption (HPKE) incorporate ephemeral Diffie-Hellman key exchanges within public-key frameworks to encapsulate symmetric keys securely, enhancing forward secrecy while maintaining compatibility with symmetric ciphers.[33][35] This conceptual hybrid model underpins many secure communication protocols, balancing security and performance effectively.[35]Protocol Examples

Public-key cryptography is integral to several widely adopted hybrid protocols, where it facilitates initial authentication and key agreement before transitioning to efficient symmetric encryption for the bulk of data transmission. These protocols leverage asymmetric mechanisms to establish trust and shared secrets securely over untrusted networks, ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity. Representative examples include the Transport Layer Security (TLS) handshake, Secure Shell (SSH), and Internet Protocol Security (IPSec) with Internet Key Exchange (IKE). In the TLS 1.3 handshake, public-key cryptography is employed for server authentication and ephemeral key agreement. The server presents an X.509 certificate containing its public key, typically based on RSA or elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), which the client verifies against a trusted certificate authority. The server then signs a handshake transcript using its private key (via algorithms like RSA-PSS or ECDSA) to prove possession and authenticity. Concurrently, the client and server perform an ephemeral Diffie-Hellman (DHE) or elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDHE) exchange using supported groups such as x25519 or secp256r1 to derive a shared secret. This secret, combined with the transcript via HKDF, generates symmetric keys for AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305 encryption of subsequent application data, embodying the hybrid model.[37] The SSH protocol utilizes public-key cryptography primarily for host and user authentication, alongside key exchange for session establishment. During the transport layer negotiation, the server authenticates itself by signing the key exchange hash with its host private key (e.g., RSA or DSA), allowing the client to verify the signature against the server's known public key. User authentication follows via the "publickey" method, where the client proves possession of a private key by signing a challenge message, supporting algorithms like ssh-rsa or ecdsa-sha2-nistp256. Key agreement occurs through Diffie-Hellman groups (e.g., group14-sha256), producing a shared secret from which symmetric session keys are derived for ciphers like AES and integrity via HMAC, securing the remote login channel.[38][39] In IPSec, public-key cryptography is optionally integrated into the IKEv2 protocol for peer authentication and key exchange during security association setup. Authentication employs digital signatures in AUTH payloads, using RSA or DSS on certificates to verify peer identities, with support for X.509 formats and identifiers like FQDN or ASN.1 distinguished names. Key exchange relies on ephemeral Diffie-Hellman (e.g., Group 14: 2048-bit modulus) to establish shared secrets with perfect forward secrecy, from which symmetric keys are derived via a pseudorandom function (PRF) like HMAC-SHA-256. These keys then protect IP traffic using Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) with symmetric algorithms such as AES in GCM mode, enabling secure VPN tunnels. While pre-shared keys are common, public-key methods enhance scalability in large deployments.[40] The following table compares these protocols in terms of public-key types and recommended security levels, based on NIST guidelines for at least 112-bit security strength (equivalent to breaking 2^112 operations).| Protocol | Key Types Used for Authentication | Key Types Used for Key Exchange | Recommended Security Levels (Key Sizes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLS 1.3 | RSA (2048 bits), ECDSA (P-256 or P-384) | ECDHE (x25519 or secp256r1, ~256 bits) | 128-bit (ECC) or 112-bit (RSA/DH) |

| SSH | RSA (2048 bits), ECDSA (P-256 or P-384), DSA | DH (2048 bits, Group 14) | 112-bit (RSA/DH) or 128-bit (ECC) |

| IPSec (IKEv2) | RSA (2048 bits), DSS (2048 bits) | DH (2048 bits, Group 14) | 112-bit (RSA/DSS/DH) |