Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Point at infinity

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

In geometry, a point at infinity or ideal point is an idealized limiting point at the "end" of each line.

In the case of an affine plane (including the Euclidean plane), there is one ideal point for each pencil of parallel lines of the plane. Adjoining these points produces a projective plane, in which no point can be distinguished, if we "forget" which points were added. This holds for a geometry over any field, and more generally over any division ring.[1]

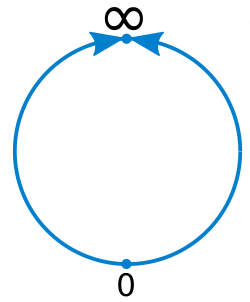

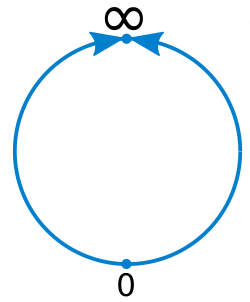

In the real case, a point at infinity completes a line into a topologically closed curve. In higher dimensions, all the points at infinity form a projective subspace of one dimension less than that of the whole projective space to which they belong. A point at infinity can also be added to the complex line (which may be thought of as the complex plane), thereby turning it into a closed surface known as the complex projective line, CP1, also called the Riemann sphere (when complex numbers are mapped to each point).

In the case of a hyperbolic space, each line has two distinct ideal points. Here, the set of ideal points takes the form of a quadric.

Affine geometry

[edit]In an affine or Euclidean space of higher dimension, the points at infinity are the points which are added to the space to get the projective completion.[citation needed] The set of the points at infinity is called, depending on the dimension of the space, the line at infinity, the plane at infinity or the hyperplane at infinity, in all cases a projective space of one less dimension.[2]

As a projective space over a field is a smooth algebraic variety, the same is true for the set of points at infinity. Similarly, if the ground field is the real or the complex field, the set of points at infinity is a manifold.

Perspective

[edit]In artistic drawing and technical perspective, the projection on the picture plane of the point at infinity of a class of parallel lines is called their vanishing point.[3]

Hyperbolic geometry

[edit]In hyperbolic geometry, points at infinity are typically named ideal points.[4] Unlike Euclidean and elliptic geometries, each line has two points at infinity: given a line l and a point P not on l, the right- and left-limiting parallels converge asymptotically to different points at infinity.

All points at infinity together form the Cayley absolute or boundary of a hyperbolic plane.

Projective geometry

[edit]A symmetry of points and lines arises in a projective plane: just as a pair of points determine a line, so a pair of lines determine a point. The existence of parallel lines leads to establishing a point at infinity which represents the intersection of these parallels. This axiomatic symmetry grew out of a study of graphical perspective where a parallel projection arises as a central projection where the center C is a point at infinity, or figurative point.[5] The axiomatic symmetry of points and lines is called duality.

Though a point at infinity is considered on a par with any other point of a projective range, in the representation of points with projective coordinates, distinction is noted: finite points are represented with a 1 in the final coordinate while a point at infinity has a 0 there. The need to represent points at infinity requires that one extra coordinate beyond the space of finite points is needed.

Other generalizations

[edit]This construction can be generalized to topological spaces. Different compactifications may exist for a given space, but arbitrary topological space admits Alexandroff extension, also called the one-point compactification when the original space is not itself compact. Projective line (over arbitrary field) is the Alexandroff extension of the corresponding field. Thus, the circle is the one-point compactification of the real line, and the sphere is the one-point compactification of the plane. Projective spaces Pn for n > 1 are not one-point compactifications of corresponding affine spaces for the reason mentioned above under § Affine geometry, and completions of hyperbolic spaces with ideal points are also not one-point compactifications.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Point at Infinity". mathworld.wolfram.com. Wolfram Research. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1987). Projective Geometry (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-387-40623-7.

- ^ Faugeras, Olivier; Luong, Quang-Tuan (2001). The Geometry of Multiple Images: The Laws That Govern the Formation of Multiple Images of a Scene and Some of Their Applications. MIT Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0262062206.

- ^ Kay, David C. (2011). College Geometry: A Unified Development. CRC Press. p. 548. ISBN 978-1-4398-9522-1.

- ^ Halsted, G. B. (1906). Synthetic Projective Geometry. New York Wiley. p. 7.