Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

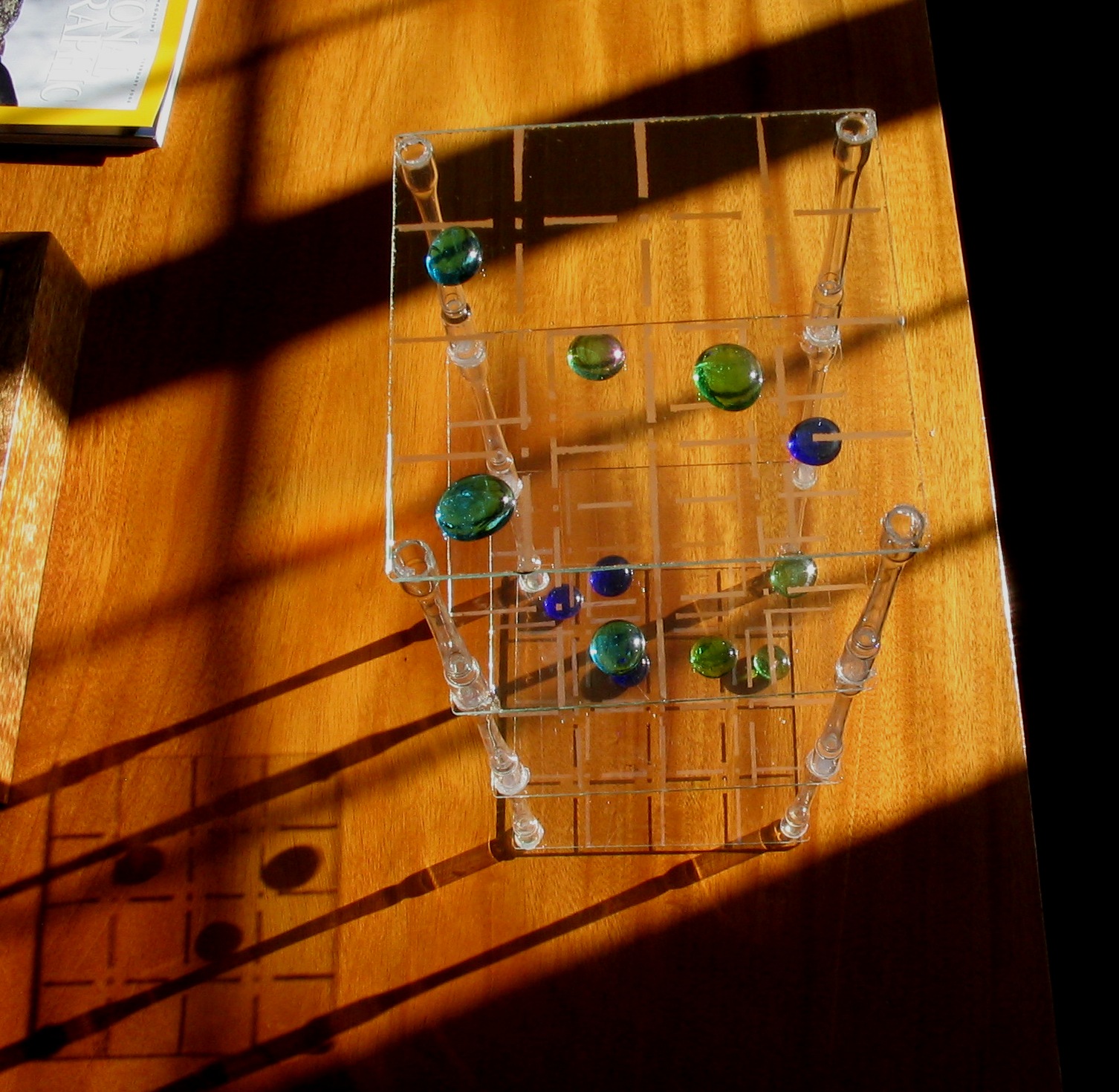

3D tic-tac-toe

View on Wikipedia

3D tic-tac-toe, also known by the trade name Qubic, is an abstract strategy board game, generally for two players. It is similar in concept to traditional tic-tac-toe but is played in a cubical array of cells, usually 4×4×4. Players take turns placing their markers in blank cells in the array. The first player to achieve four of their own markers in a row wins. The winning row can be horizontal, vertical, or diagonal on a single board as in regular tic-tac-toe, or vertically in a column, or a diagonal line through four boards.

As with traditional tic-tac-toe, several commercial sets of apparatus have been sold for the game, and it may also be played with pencil and paper with a hand-drawn board.

The game has been analyzed mathematically and a first-player-win strategy was developed and published. However, the strategy is too complicated for most human players to memorize and apply.

Pencil and paper

[edit]Like traditional 3×3 tic-tac-toe, the game may be played with pencil and paper. A game board can easily be drawn by hand, with players using the usual "naughts and crosses" to mark their moves.

In the 1970s, 3M Games (a division of 3M Corporation) sold a series of "Paper Games", including "3 Dimensional Tic Tac Toe". Buyers received a pad of 50 sheets with preprinted game boards.[1]

Marker sizes variation

[edit]Gobblets Gobbler[2] and Otrio,[3] use marker sizes (small, medium, large) as the replacement of the third element. Players can 'steal' the opponent spot by placing larger marker at the top of the opponent smaller marker or just simply competing with overlapping spot.

"Qubic"

[edit]"Qubic" is the brand name of equipment for the 4×4×4 game that was manufactured and marketed by Parker Brothers, starting in 1964.[4] It was reissued in 1972 with a more modern design. Both versions described the game as "Parker Brothers 3D Tic Tac Toe Game".

In the original issue, the bottom level board was opaque plastic, and the upper three clear, all of simple square design. The 1972 reissue used four clear plastic boards with rounded corners. Whereas pencil and paper play almost always involves just two players, Parker Brothers' rules said that up to three players could play. The circular playing pieces resembled small poker chips in red, blue, and yellow.

The game is no longer manufactured.

Reviews

[edit]Gameplay and analysis

[edit]3×3×3, two-player

[edit]The 3×3×3 version of the game cannot end in a draw[6] and is easily won by the first player unless a rule is adopted that prevents the first player from taking the center cell on his first step. In that case, the game is easily won by the second player. By banning the use of the center cell altogether, the game is easily won by the first player. By including a 3rd player, the perfect game will be played out to a draw. By including stochasticity in the choosing of the side the player must use, the game becomes fair and winnable by all players but is subject to chance. By making the choice of the player piece (× or ⚬) subject to chance, the game becomes fair and winnable by all players.[7]

4×4×4, two-player

[edit]On the 4×4×4 board, there are 76 winning lines: 48 that are parallel to an edge of the cube, 24 that are parallel to a face diagonal, and finally 4 body diagonals of the cube.

The 16 cells lying on these latter four lines (that is, the eight corner cells and eight internal cells) are each included in seven different winning lines; the other 48 cells (24 face cells and 24 edge cells) are each included in four winning lines.

The corner cells and the internal cells are actually equivalent via an automorphism; likewise for face and edge cells. The group of automorphisms of the game contains 192 automorphisms. It is made up of combinations of the usual rotations and reflections that reorient or reflect the cube, plus two that scramble the order of cells on each line. If a line comprises cells A, B, C and D in that order, one of these exchanges inner cells for outer ones (such as B, A, D, C) for all lines of the cube, and the other exchanges cells of either the inner or the outer cells (A, C, B, D or equivalently D, B, C, A) for all lines of the cube. Combinations of these basic automorphisms generate the entire group of 192 as shown by R. Silver in 1967.[8]

3D tic-tac-toe was weakly solved, meaning that the existence of a winning strategy was proven but without actually presenting such a strategy, by Eugene Mahalko in 1976.[9] He proved that in two-person play, the first player will win if there are two optimal players.

A more complete analysis, including the announcement of a complete first-player-win strategy, was published by Oren Patashnik in 1980.[10] Patashnik used a computer-assisted proof that consumed 1500 hours of computer time. The strategy comprised move choices for 2929 difficult "strategic" positions, plus assurances that all other positions that could arise could be easily won with a sequence entirely made up of forcing moves. It was further asserted that the strategy had been independently verified. As computer storage became cheaper and the internet made it possible, these positions and moves were made available online.[11]

The game was solved again by Victor Allis using proof-number search.[12]

Computer implementations

[edit]| 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe | |

|---|---|

Atari 2600 box art | |

| Developer | Atari, Inc. |

| Publishers | Atari, Inc. |

| Programmer | Carol Shaw |

| Platforms | Atari 2600, Atari 8-bit |

| Release | July 1980[13] |

| Modes | Single-player, multiplayer |

Several computer programs that play the game against a human opponent have been written. The earliest of these used console lights and switches, text terminals, or similar interaction: the human player would enter moves numerically (for example, using "4 2 3" for fourth level, second row, third column) and the program would respond similarly, as graphics displays were uncommon.

A program written for the IBM 650 used front panel switches and lights for the user interface.[citation needed]

William Daly Jr. wrote and described a Qubic-playing program as part of his Master's program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The program was written in assembler language for the TX-0 computer. It included lookahead to 12 moves and kept a history of previous games with each opponent, modifying its strategy according to their past behavior.[14]

An implementation in Fortran was written by Robert K. Louden and presented, with an extensive description of its design, in his book Programming the IBM 1130 and 1800. Its strategy involved looking for combinations of one or two free cells shared among two or three rows with particular contents.[15]

A Qubic program in a DEC dialect of BASIC appeared in 101 BASIC Computer Games by David H. Ahl.[16] Ahl said the program "showed up", author unknown, on a G.E. timesharing system in 1968.

Atari released a 4x4x4 graphical version of the game for the Atari 2600 console and Atari 8-bit computers in 1980.[17][18] The program was written by Carol Shaw, who went on to greater fame as the creator of Activision's River Raid.[19] It uses the standard joystick controller. It can be played by two players against each other, or one player can play against the program on one of eight different difficulty settings.[20] The product code for the Atari game was CX-2618.[21]

Three-dimensional tic-tac-toe on a 4x4x4 board (optionally 3x3x3) was included in the Microsoft Windows Entertainment Pack in the 1990s under the name TicTactics. In 2010, Microsoft made the game available on its Game Room service for its Xbox 360 console.

A program library named Qubist, and front-end for the GTK 2 window library are a project on SourceForge.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gaming Unplugged Since 2000". BoardGameGeek.

- ^ McFeetors, P. Janelle; Palfy, Kylie (May 1, 2017). "We're in Math Class Playing Games, Not Playing Games in Math Class". Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School. 22 (9): 534–544. doi:10.5951/mathteacmiddscho.22.9.0534.

- ^ Kubota, Runa; Troillet, Lucien; Matsuzaki, Kiminori (December 2022). "Three Player Otrio will be Strongly Solved". 2022 International Conference on Technologies and Applications of Artificial Intelligence (TAAI). pp. 30–35. doi:10.1109/TAAI57707.2022.00015. ISBN 979-8-3503-9950-9. S2CID 257408458.

- ^ "Trademark Status & Document Retrieval (TSDR)". United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- ^ Freeman, Jon; Jackson, John (August 6, 1979). "The Playboy winner's guide to board games". Chicago : Playboy Press. Retrieved August 6, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Tic-tac-toe game on the cube 3×3×3

- ^ Golomb, Solomon W.; Hales, Alfred W. (August 2002). "Hypercube Tic-Tac-Toe". In Nowakowski, Richard (ed.). More Games of No Chance. Mathematical Sciences Research Institute Publications. Vol. 42. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521155632.

- ^ R. Silver (March 1967). "The group of automorphisms of the game of 3-dimensional ticktacktoe". Amer. Math. Monthly. 74 (3). Mathematical Association of America: 247–254. doi:10.2307/2316015. JSTOR 2316015.

- ^ Eugene D. Mahalko (1976). A Possible Win Strategy for the Game of Qubic (M.Sc. thesis). Brigham Young University.

- ^ Oren Patashnik (September 1980). "Qubic: 4 x 4 x 4 Tic-Tac-Toe". Mathematics Magazine. 53 (4): 202–216. JSTOR 2689613.

- ^ "qubic.dictionary". Google Docs. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ L .V. Allis & P. N. A. Schoo (1992). "Qubic solved again". In H. J. van den Herik & L. V. Allis (eds.). Heuristic Programming in Artificial Intelligence 3: The Third Computer Olympiad. Ellis Horwood, Chichester, UK. pp. 192–204.

- ^ "Atari VCS game release dates". Atari Archive.

- ^ William George Daly Jr. (February 1961). Computer Strategies for the Game of Qubic (PDF) (M.Sc.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Robert K. Louden (1967). "Integer manipulation in FORTRAN". Programming the IBM 1130 and 1800. Prentice-Hall. pp. 179–204. ASIN B0006BRBTQ.

- ^ David H. Ahl (1975). 101 BASIC Computer Games (PDF). Digital Equipment Corporation. pp. 175–177.

- ^ "Atari 2600 VCS 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe". Atari Mania. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ "3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Release Information for Atari 2600 - GameFAQs".

- ^ "AtariAge - Programmers - Carol Shaw". Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ "3-D Tic-Tac-Toe at MobyGames".

- ^ "(Atari Ad)". The San Bernardino County Sun (San Bernardino, California). August 5, 1981. Retrieved August 6, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Qubist source code". SourceForge. December 12, 2018.