Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shewanella

View on Wikipedia

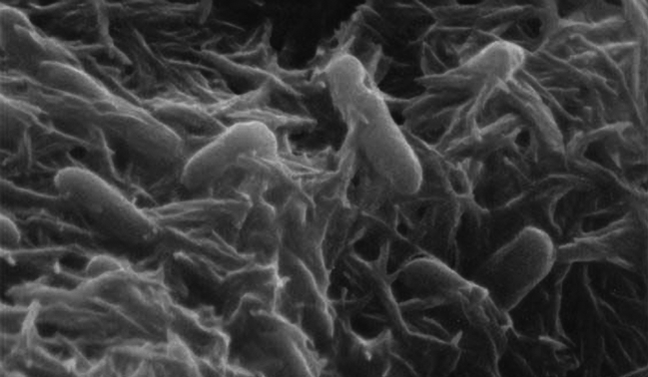

Shewanella is the sole genus included in the marine bacteria family Shewanellaceae. Some species within it were formerly classed as Alteromonas. Shewanella consists of facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative rods, most of which are found in extreme aquatic habitats where the temperature is very low and the pressure is very high.[2] Shewanella bacteria are a normal component of the surface flora of fish and are implicated in fish spoilage.[3] Shewanella chilikensis is a species of the genus Shewanella commonly found in the marine sponges of Saint Martin's Island of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh.[4]

Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is a widely used laboratory model to study anaerobic respiration of metals and other anaerobic extracellular electron acceptors, and for teaching about microbial electrogenesis and microbial fuel cells.[5]

Biochemical characteristics of Shewanella species

[edit]Colony, morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics of Shewanella species are shown in the Table below.[4]

| Test type | Test | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Colony characters | Size | Small, Medium |

| Type | Round | |

| Color | Brownish, Pinkish | |

| Shape | Convex | |

| Morphological characters | Shape | Rod |

| Physiological characters | Motility | + |

| Growth at 6.5% NaCl | + | |

| Biochemical characters | Gram's staining | – |

| Oxidase | + | |

| Catalase | + | |

| Oxidative-Fermentative | Fermentative | |

| Motility | + | |

| Methyl Red | – | |

| Voges-Proskauer | – | |

| Indole | – | |

| H2S Production | + | |

| Urease | + | |

| Nitrate reductase | – | |

| β-Galactosidase | + | |

| Hydrolysis of | Gelatin | – |

| Aesculin | + | |

| Casein | + | |

| Tween 40 | + | |

| Tween 60 | + | |

| Tween 80 | + | |

| Acid production from | Glycerol | – |

| Galactose | – | |

| D-Glucose | + | |

| D-Fructose | + | |

| D-Mannose | + | |

| Mannitol | + | |

| N-Acetylglucosamine | + | |

| Amygdalin | + | |

| Maltose | + | |

| D-Melibiose | + | |

| D-Trehalose | + | |

| Glycogen | + | |

| D-Turanose | + |

Note: + = Positive; – =Negative

Metabolism

[edit]Currently known Shewanella species are heterotrophic facultative anaerobes.[6] In the absence of oxygen, members of this genus possess capabilities allowing the use of a variety of other electron acceptors for respiration. These include thiosulfate, sulfite, or elemental sulfur,[7] as well as fumarate.[8] Marine species have demonstrated an ability to use arsenic as an electron acceptor as well.[9] Some members of this species, most notably Shewanella oneidensis, have the ability to respire through a wide range of metal species, including manganese, chromium, uranium, and iron.[10] Reduction of iron and manganese through Shewanella respiration has been shown to involve extracellular electron transfer through the employment of bacterial nanowires, extensions of the outer membrane.[11]

Applications

[edit]The discovery of some of the respiratory capabilities possessed by members of this genus has opened the door to possible applications for these bacteria. The metal-reducing capabilities can potentially be applied to bioremediation of uranium-contaminated groundwater,[12] with the reduced form of uranium produced being easier to remove from water than the more soluble uranium oxide. Scientists researching the creation of microbial fuel cells, designs that use bacteria to induce a current, have also made use of the metal reducing capabilities some species of Shewanella possess as a part of their metabolic repertoire.[13]

Significance

[edit]One of the roles that the genus Shewanella has in the environment is bioremediation.[14] Shewanella species have great metabolic versatility; they can reduce various electron acceptors.[2] Some of the electron acceptors they use are toxic substances and heavy metals, which often become less toxic after being reduced.[14] Examples of metals that Shewanella are capable of reducing and degrading include uranium, chromium, and iron.[15] Its ability to decrease toxicity of various substances makes Shewanella a useful tool for bioremediation. Specifically, Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 is often used to clean up contaminated nuclear weapon manufacturing sites.[15]

Shewanella also contributes to the biogeochemical circulation of minerals.[2] Members of this genus are widely distributed in aquatic habitats, from the deep sea to the shallow Antarctic Ocean.[14] Its diverse habitats, coupled to its ability to reduce a variety of metals, makes the genus critical for the cycling of minerals.[2] For instance, under aerobic conditions, various species of Shewanella are capable of oxidizing manganese.[16] When conditions are changed, the same species can reduce the manganese oxide products.[16] Hence, since Shewanella can both oxidize and reduce manganese, it is critical to the cycling of manganese.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u LPSN lpsn.dsmz.de

- ^ a b c d Endotoxins : Structure, function and recognition. Wang, Xiaoyuan., Quinn, Peter J. Dordrecht: Springer Verlag. 2010. ISBN 978-9048190782. OCLC 663096120.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Adams and Moss, Food Microbiology, third edition 2008, pp 26, 138, 140,

- ^ a b Paul, Sulav Indra; Rahman, Md. Mahbubur; Salam, Mohammad Abdus; Khan, Md. Arifur Rahman; Islam, Md. Tofazzal (2021-12-15). "Identification of marine sponge-associated bacteria of the Saint Martin's island of the Bay of Bengal emphasizing on the prevention of motile Aeromonas septicemia in Labeo rohita". Aquaculture. 545 737156. Bibcode:2021Aquac.54537156P. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737156. ISSN 0044-8486.

- ^ Gorby, Yuri A.; Yanina, Svetlana; McLean, Jeffrey S.; Rosso, Kevin M.; Moyles, Dianne; Dohnalkova, Alice; Beveridge, Terry J.; Chang, In Seop; Kim, Byung Hong (2006-07-25). "Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (30): 11358–11363. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10311358G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604517103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1544091. PMID 16849424.

- ^ Serres, Genomic Analysis of Carbon Source Metabolism of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1: Predictions versus Experiments, Journal of Bacteriology, July 2006

- ^ Burns, Anaerobic Respiration of Elemental Sulfur and Thiosulfate by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 Requires psrA, a Homolog of the phsA Gene of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium LT2, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 19 June 2009

- ^ Pinchuk et al., Pyruvate and lactate metabolism by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 under fermentation, oxygen limitation, and fumarate respiration conditions., Applied and Environmental Microbiology December 2011

- ^ Saltikov et al., Expression Dynamics of Arsenic Respiration and Detoxification in Shewanella sp. Strain ANA-3, Journal of Bacteriology, Nov 2005

- ^ Tiedje, Shewanella—the environmentally versatile genome, Nature Biotechnology

- ^ Pirbadian et al., Bacterial Nanowires of Shewanella Oneidensis MR-1 are Outer Membrane and Periplasmic Extensions of the Extracellular Electron Transport Components, Biophysical Journal, Volume 108, Jan 2015

- ^ Newsome, The biogeochemistry and bioremediation of uranium and other priority radionuclides, Chemical Geology, Volume 363, pp 164-184, 10 Jan 2014,

- ^ Hoffman et al., Dual-chambered bio-batteries using immobilized mediator electrodes, Journal of Applied Electrochemistry, Vol 43, Issue 7, pp 629–636, 27 Apr 2013

- ^ a b c Dikow, Rebecca B. (2011-05-12). "Genome-level homology and phylogeny of Shewanella (Gammaproteobacteria: lteromonadales: Shewanellaceae)". BMC Genomics. 12 237. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-237. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 3107185. PMID 21569439.

- ^ a b Tim., Friend (2007). The third domain : the untold story of archaea and the future of biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0309102377. OCLC 228173040.

- ^ a b c Wright, Mitchell H.; Farooqui, Saad M.; White, Alan R.; Greene, Anthony C. (2016-08-15). "Production of Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles by Shewanella Species". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 82 (17): 5402–5409. Bibcode:2016ApEnM..82.5402W. doi:10.1128/AEM.00663-16. ISSN 0099-2240. PMC 4988204. PMID 27342559.

- ^ NEW TAXA - Proteobacteria: Kim, D. (2007). "Shewanella haliotis sp. nov., isolated from the gut microflora of abalone, Haliotis discus hannai". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 57 (12): 2926–2931. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.65257-0. PMID 18048751.