Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gloss (optics)

View on Wikipedia

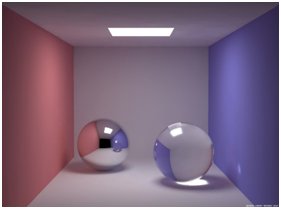

Gloss is an optical property which indicates how well a surface reflects light in a specular (mirror-like) direction. It is one of the important parameters that are used to describe the visual appearance of an object. Other categories of visual appearance related to the perception of regular or diffuse reflection and transmission of light have been organized under the concept of cesia in an order system with three variables, including gloss among the involved aspects. The factors that affect gloss are the refractive index of the material, the angle of incident light and the surface texture.

Apparent gloss depends on the amount of specular reflection – light reflected from the surface in an equal amount and the symmetrical angle to the one of incoming light – in comparison with diffuse reflection – the amount of light scattered into other directions.

Theory

[edit]

When light illuminates an object, it interacts with it in a number of ways:

- Absorbed within it (largely responsible for colour)

- Transmitted through it (dependent on the surface transparency and opacity)

- Scattered from or within it (diffuse reflection, haze and transmission)

- Specularly reflected from it (gloss)

Variations in surface texture directly influence the level of specular reflection. Objects with a smooth surface, i.e. highly polished or containing coatings with finely dispersed pigments, appear shiny to the eye due to a large amount of light being reflected in a specular direction whilst rough surfaces reflect no specular light as the light is scattered in other directions and therefore appears dull. The image forming qualities of these surfaces are much lower making any reflections appear blurred and distorted.

Substrate material type also influences the gloss of a surface. Non-metallic materials, i.e. plastics etc. produce a higher level of reflected light when illuminated at a greater illumination angle due to light being absorbed into the material or being diffusely scattered depending on the colour of the material. Metals do not suffer from this effect producing higher amounts of reflection at any angle.

The Fresnel formula gives the specular reflectance, , for an unpolarized light of intensity , at angle of incidence , giving the intensity of specularly reflected beam of intensity , while the refractive index of the surface specimen is .

The Fresnel equation is given as follows :

Surface roughness

[edit]

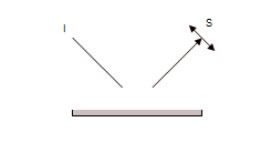

Surface roughness influences the specular reflectance levels; in the visible frequencies, the surface finish in the micrometre range is most relevant. The diagram on the right depicts the reflection at an angle on a rough surface with a characteristic roughness height variation . The path difference between rays reflected from the top and bottom of the surface bumps is:

When the wavelength of the light is , the phase difference will be:

If is small, the two beams (see Figure 1) are nearly in phase, resulting in constructive interference; therefore, the specimen surface can be considered smooth. But when , then beams are not in phase and through destructive interference, cancellation of each other will occur. Low intensity of specularly reflected light means the surface is rough and it scatters the light in other directions. If the middle phase value is taken as criterion for smooth surface, , then substitution into the equation above will produce:

This smooth surface condition is known as the Rayleigh roughness criterion.

History

[edit]The earliest studies of gloss perception are attributed to Leonard R. Ingersoll[1][2] who in 1914 examined the effect of gloss on paper.[non-primary source needed] By quantitatively measuring gloss using instrumentation Ingersoll based his research around the theory that light is polarised in specular reflection whereas diffusely reflected light is non-polarized. The Ingersoll "glarimeter" had a specular geometry with incident and viewing angles at 57.5°. Using this configuration gloss was measured using a contrast method which subtracted the specular component from the total reflectance using a polarizing filter.

In the 1930s work by A. H. Pfund,[3] suggested that although specular shininess is the basic (objective) evidence of gloss, actual surface glossy appearance (subjective) relates to the contrast between specular shininess and the diffuse light of the surrounding surface area (now called "contrast gloss" or "luster").[non-primary source needed]

If black and white surfaces of the same shininess are visually compared, the black surface will always appear glossier because of the greater contrast between the specular highlight and the black surroundings as compared to that with white surface and surroundings. Pfund was also the first to suggest that more than one method was needed to analyze gloss correctly.

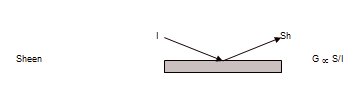

In 1937 R. S. Hunter,[4] as part of his research paper on gloss, described six different visual criteria attributed to apparent gloss.[non-primary source needed] The following diagrams show the relationships between an incident beam of light, I, a specularly reflected beam, S, a diffusely reflected beam, D and a near-specularly reflected beam, B.

- Specular gloss – the perceived brightness and the brilliance of highlights

Defined as the ratio of the light reflected from a surface at an equal but opposite angle to that incident on the surface.

- Sheen – the perceived shininess at low grazing angles

Defined as the gloss at grazing angles of incidence and viewing

- Contrast gloss – the perceived brightness of specularly and diffusely reflecting areas

Defined as the ratio of the specularly reflected light to that diffusely reflected normal to the surface;

- Absence of bloom – the perceived cloudiness in reflections near the specular direction

Defined as a measure of the absence of haze or a milky appearance adjacent to the specularly reflected light: haze is the inverse of absence-of-bloom

- Distinctness of image gloss – identified by the distinctness of images reflected in surfaces

Defined as the sharpness of the specularly reflected light

- Surface texture gloss – identified by the lack of surface texture and surface blemishes

Defined as the uniformity of the surface in terms of visible texture and defects (orange peel, scratches, inclusions etc.)

A surface can therefore appear very shiny if it has a well-defined specular reflectance at the specular angle. The perception of an image reflected in the surface can be degraded by appearing unsharp, or by appearing to be of low contrast. The former is characterised by the measurement of the distinctness-of-image and the latter by the haze or contrast gloss.

In his paper Hunter also noted the importance of three main factors in the measurement of gloss:

- The amount of light reflected in the specular direction

- The amount and way in which the light is spread around the specular direction

- The change in specular reflection as the specular angle changes

For his research he used a glossmeter with a specular angle of 45° as did most of the first photoelectric methods of that type, later studies however by Hunter and D. B. Judd in 1939,[5] on a larger number of painted samples, concluded that the 60 degree geometry was the best angle to use so as to provide the closest correlation to a visual observation.[non-primary source needed]

Standard gloss measurement

[edit]Standardisation in gloss measurement was led by Hunter and ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) who produced ASTM D523 Standard test method for specular gloss in 1939. This incorporated a method for measuring gloss at a specular angle of 60°. Later editions of the Standard (1951) included methods for measuring at 20° for evaluating high gloss finishes, developed at the DuPont Company (Horning and Morse, 1947) and 85° (matte, or low, gloss).

ASTM has a number of other gloss-related standards designed for application in specific industries including the old 45° method which is used primarily now used for glazed ceramics, polyethylene and other plastic films.

In 1937, the paper industry adopted a 75° specular-gloss method because the angle gave the best separation of coated book papers.[6] This method was adopted in 1951 by the Technical Association of Pulp and Paper Industries as TAPPI Method T480.

In the paint industry, measurements of the specular gloss are made according to International Standard ISO 2813 (BS 3900, Part 5, UK; DIN 67530, Germany; NFT 30-064, France; AS 1580, Australia; JIS Z8741, Japan, are also equivalent). This standard is essentially the same as ASTM D523 although differently drafted.

Studies of polished metal surfaces and anodised aluminium automotive trim in the 1960s by Tingle,[7][8] Potter and George led to the standardisation of gloss measurement of high gloss surfaces by goniophotometry under the designation ASTM E430. In this standard it also defined methods for the measurement of distinctness of image gloss and reflection haze.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ingersoll Elec. World 63,645 (1914), Elec. World 64, 35 (1915); Paper 27, 18 (Feb. 9, 1921), and U. S. Patent 1225250 (May 8, 1917)

- ^ Ingersoll R. S., The Glarimeter, "An instrument for measuring the gloss of paper". J.Opt. Soc. Am. 5.213 (1921)

- ^ A. H. Pfund, "The measurement of gloss", J. Opt. Soc. Am. 20, 23.23 (1930)

- ^ Hunter, Richard S. (January 1937), "Methods of Determining Gloss" (PDF), Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, vol. 18, NBS Research Paper, doi:10.6028/jres.018.006, RP 958

- ^ Judd, D B (1937), Gloss and glossiness. Am. Dyest. Rep. 26, 234–235

- ^ Institute of Paper Chemistry (1937); Hunter (1958)

- ^ Tingle, W. H., and Potter, F. R., “New Instrument Grades for Polished Metal Surfaces,” Product Engineering, Vol 27, March 1961.

- ^ Tingle, W. H., and George, D. J., “Measuring Appearance Characteristics of Anodized Aluminum Automotive Trim,” Report No. 650513, Society of Automotive Engineers, May 1965.

Sources

[edit]- Koleske, J.V. (2011). "Part 10". Paint and Coating Test Manual. USA: ASTM. ISBN 978-0-8031-7017-9.

- Meeten, G.H. (1986). Optical Properties of Polymers. London: Elsevier Applied Science. pp. 326–329. ISBN 0-85334-434-5.

![{\displaystyle R_{s}={\frac {1}{2}}\left[\left({\frac {\cos i-{\sqrt {m^{2}-\sin ^{2}i}}}{\cos i+{\sqrt {m^{2}-\sin ^{2}i}}}}\right)^{2}+\left({\frac {m^{2}\cos i-{\sqrt {m^{2}-\sin ^{2}i}}}{m^{2}\cos i+{\sqrt {m^{2}-\sin ^{2}i}}}}\right)^{2}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/edf132fcf032bbd8ad4957c364c8a259be4a352c)