Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reflectance

View on Wikipedia

The reflectance of the surface of a material is its effectiveness in reflecting radiant energy. It is the fraction of incident electromagnetic power that is reflected at the boundary. Reflectance is a component of the response of the electronic structure of the material to the electromagnetic field of light, and is in general a function of the frequency, or wavelength, of the light, its polarization, and the angle of incidence. The dependence of reflectance on the wavelength is called a reflectance spectrum or spectral reflectance curve.

Mathematical definitions

[edit]Hemispherical reflectance

[edit]The hemispherical reflectance of a surface, denoted R, is defined as[1] where Φer is the radiant flux reflected by that surface and Φei is the radiant flux received by that surface.

Spectral hemispherical reflectance

[edit]The spectral hemispherical reflectance in frequency and spectral hemispherical reflectance in wavelength of a surface, denoted Rν and Rλ respectively, are defined as[1] where

- Φe,νr is the spectral radiant flux in frequency reflected by that surface;

- Φe,νi is the spectral radiant flux in frequency received by that surface;

- Φe,λr is the spectral radiant flux in wavelength reflected by that surface;

- Φe,λi is the spectral radiant flux in wavelength received by that surface.

Directional reflectance

[edit]The directional reflectance of a surface, denoted RΩ, is defined as[1] where

- Le,Ωr is the radiance reflected by that surface;

- Le,Ωi is the radiance received by that surface.

This depends on both the reflected direction and the incoming direction. In other words, it has a value for every combination of incoming and outgoing directions. It is related to the bidirectional reflectance distribution function and its upper limit is 1. Another measure of reflectance, depending only on the outgoing direction, is I/F, where I is the radiance reflected in a given direction and F is the incoming radiance averaged over all directions, in other words, the total flux of radiation hitting the surface per unit area, divided by π.[2] This can be greater than 1 for a glossy surface illuminated by a source such as the sun, with the reflectance measured in the direction of maximum radiance (see also Seeliger effect).

Spectral directional reflectance

[edit]The spectral directional reflectance in frequency and spectral directional reflectance in wavelength of a surface, denoted RΩ,ν and RΩ,λ respectively, are defined as[1] where

- Le,Ω,νr is the spectral radiance in frequency reflected by that surface;

- Le,Ω,νi is the spectral radiance received by that surface;

- Le,Ω,λr is the spectral radiance in wavelength reflected by that surface;

- Le,Ω,λi is the spectral radiance in wavelength received by that surface.

Again, one can also define a value of I/F (see above) for a given wavelength.[3]

Reflectivity

[edit]

For homogeneous and semi-infinite (see halfspace) materials, reflectivity is the same as reflectance. Reflectivity is the square of the magnitude of the Fresnel reflection coefficient,[4] which is the ratio of the reflected to incident electric field;[5] as such the reflection coefficient can be expressed as a complex number as determined by the Fresnel equations for a single layer, whereas the reflectance is always a positive real number.

For layered and finite media, according to the CIE,[citation needed] reflectivity is distinguished from reflectance by the fact that reflectivity is a value that applies to thick reflecting objects.[6] When reflection occurs from thin layers of material, internal reflection effects can cause the reflectance to vary with surface thickness. Reflectivity is the limit value of reflectance as the sample becomes thick; it is the intrinsic reflectance of the surface, hence irrespective of other parameters such as the reflectance of the rear surface. Another way to interpret this is that the reflectance is the fraction of electromagnetic power reflected from a specific sample, while reflectivity is a property of the material itself, which would be measured on a perfect machine if the material filled half of all space.[7]

Surface type

[edit]Given that reflectance is a directional property, most surfaces can be divided into those that give specular reflection and those that give diffuse reflection.

For specular surfaces, such as glass or polished metal, reflectance is nearly zero at all angles except at the appropriate reflected angle; that is the same angle with respect to the surface normal in the plane of incidence, but on the opposing side. When the radiation is incident normal to the surface, it is reflected back into the same direction.

For diffuse surfaces, such as matte white paint, reflectance is uniform; radiation is reflected in all angles equally or near-equally. Such surfaces are said to be Lambertian.

Most practical objects exhibit a combination of diffuse and specular reflective properties.

Liquid reflectance

[edit]

Reflection of light occurs at a boundary at which the index of refraction changes. Specular reflection is calculated by the Fresnel equations.[8] Fresnel reflection is directional and therefore does not contribute significantly to albedo which primarily diffuses reflection.

A liquid surface may be wavy. Reflectance may be adjusted to account for waviness.

Grating efficiency

[edit]The generalization of reflectance to a diffraction grating, which disperses light by wavelength, is called diffraction efficiency.

Other radiometric coefficients

[edit]| Quantity | SI units | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Sym. | ||

| Hemispherical emissivity | ε | — | Radiant exitance of a surface, divided by that of a black body at the same temperature as that surface. |

| Spectral hemispherical emissivity | εν ελ |

— | Spectral exitance of a surface, divided by that of a black body at the same temperature as that surface. |

| Directional emissivity | εΩ | — | Radiance emitted by a surface, divided by that emitted by a black body at the same temperature as that surface. |

| Spectral directional emissivity | εΩ,ν εΩ,λ |

— | Spectral radiance emitted by a surface, divided by that of a black body at the same temperature as that surface. |

| Hemispherical absorptance | A | — | Radiant flux absorbed by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. This should not be confused with "absorbance". |

| Spectral hemispherical absorptance | Aν Aλ |

— | Spectral flux absorbed by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. This should not be confused with "spectral absorbance". |

| Directional absorptance | AΩ | — | Radiance absorbed by a surface, divided by the radiance incident onto that surface. This should not be confused with "absorbance". |

| Spectral directional absorptance | AΩ,ν AΩ,λ |

— | Spectral radiance absorbed by a surface, divided by the spectral radiance incident onto that surface. This should not be confused with "spectral absorbance". |

| Hemispherical reflectance | R | — | Radiant flux reflected by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Spectral hemispherical reflectance | Rν Rλ |

— | Spectral flux reflected by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Directional reflectance | RΩ | — | Radiance reflected by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Spectral directional reflectance | RΩ,ν RΩ,λ |

— | Spectral radiance reflected by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Hemispherical transmittance | T | — | Radiant flux transmitted by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Spectral hemispherical transmittance | Tν Tλ |

— | Spectral flux transmitted by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Directional transmittance | TΩ | — | Radiance transmitted by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Spectral directional transmittance | TΩ,ν TΩ,λ |

— | Spectral radiance transmitted by a surface, divided by that received by that surface. |

| Hemispherical attenuation coefficient | μ | m−1 | Radiant flux absorbed and scattered by a volume per unit length, divided by that received by that volume. |

| Spectral hemispherical attenuation coefficient | μν μλ |

m−1 | Spectral radiant flux absorbed and scattered by a volume per unit length, divided by that received by that volume. |

| Directional attenuation coefficient | μΩ | m−1 | Radiance absorbed and scattered by a volume per unit length, divided by that received by that volume. |

| Spectral directional attenuation coefficient | μΩ,ν μΩ,λ |

m−1 | Spectral radiance absorbed and scattered by a volume per unit length, divided by that received by that volume. |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Thermal insulation — Heat transfer by radiation — Physical quantities and definitions". ISO 9288:1989. ISO catalogue. 1989. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ Cuzzi, Jeffrey; Chambers, Lindsey; Hendrix, Amanda (Oct 21, 2016). "Rough Surfaces: is the dark stuff just shadow?". Icarus. 289: 281–294. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.10.018. PMC 6839776. PMID 31708591.

- ^ See for example P.G.J Irwin; et al. (Jan 12, 2022). "Hazy Blue Worlds: A Holistic Aerosol Model for Uranus and Neptune, Including Dark Spots". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 127 (6) e2022JE007189. arXiv:2201.04516. Bibcode:2022JGRE..12707189I. doi:10.1029/2022JE007189. hdl:1983/65ee78f0-1d28-4017-bbd9-1b49b24700d7. PMC 9286428. PMID 35865671. S2CID 245877540.

- ^ E. Hecht (2001). Optics (4th ed.). Pearson Education. ISBN 0-8053-8566-5.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Reflectance". doi:10.1351/goldbook.R05235

- ^ "CIE International Lighting Vocabulary". Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

- ^ Palmer and Grant, The Art of Radiometry

- ^ Ottaviani, M. and Stamnes, K. and Koskulics, J. and Eide, H. and Long, S.R. and Su, W. and Wiscombe, W., 2008: 'Light Reflection from Water Waves: Suitable Setup for a Polarimetric Investigation under Controlled Laboratory Conditions. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 25 (5), 715--728.

External links

[edit]- Reflectivity of metals Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- Reflectance Data.

Reflectance

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Principles

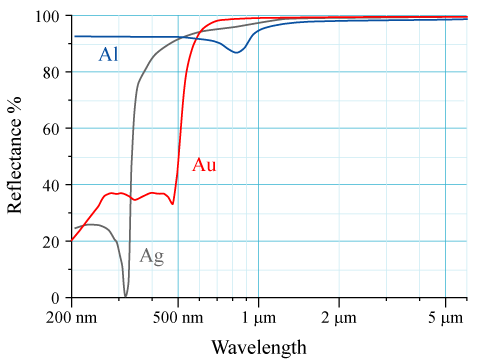

Reflectance is defined as the fraction of incident electromagnetic radiant power, or flux, that is reflected by a surface at the boundary between two media. It is a dimensionless quantity, typically denoted by ρ, and ranges from 0, indicating perfect absorption with no reflection, to 1, representing perfect reflection of all incident power. The basic equation for total reflectance is given by where is the reflected radiant power and is the incident radiant power. This formulation arises from conservation of energy principles in radiometry and applies to optical radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum.[7] The value of reflectance depends on several key factors, including the wavelength of the incident radiation, the polarization state of the light, the angle of incidence, and the physical and chemical properties of the surface, such as its roughness, composition, and microstructure. For instance, at interfaces involving dielectrics or metals, these dependencies lead to variations that can be described through more specialized functions, though the core concept remains the ratio of reflected to incident power. The term reflectance has been formalized in international radiometry standards, such as ISO 80000-7, which specifies quantities for light and optical radiation, including the spectral variant ρ(λ) as the ratio of reflected to incident spectral radiant flux. Early studies on reflection laws date back to Pierre Bouguer's 1729 work Essai d'optique sur la gradation de la lumière, where he conducted the first goniophotometric measurements of reflectance at varying angles of incidence for surfaces like water and glass, laying foundational principles for quantitative photometry.[7][8] Spectral reflectance curves illustrate this wavelength dependence for common materials used in mirrors. For example, evaporated aluminum coatings show high reflectance, often exceeding 90%, from the ultraviolet through the visible spectrum up to about 2 μm in the near-infrared, making it suitable for broadband applications. Silver coatings achieve even higher reflectance, typically above 95% in the visible range (400–700 nm) and extending into the near-infrared, though they oxidize more readily. In contrast, gold mirrors exhibit lower reflectance in the visible (around 40–50% at 500 nm) but increase sharply to over 98% in the mid-infrared beyond 2 μm, due to the material's electronic structure. These behaviors are critical for selecting materials in optical systems, as documented in standard reference measurements.[9][10]Reflectance versus Reflectivity

Reflectivity refers to the intrinsic property of a material to reflect radiation, defined as the reflectance of a layer thick enough that further increases in thickness do not change the value.[11] In contrast, reflectance is the measured ratio of the radiant flux reflected by a specific sample to the incident flux, incorporating effects such as sample thickness, surface imperfections, and geometry.[11] For homogeneous, thick samples, the two terms are equivalent, but they diverge for thin films or layered structures where interference and multiple internal reflections influence the overall reflection.[11] The International Commission on Illumination (CIE) formalizes this distinction in its International Lighting Vocabulary, adopting a convention where terms ending in "-ivity" (e.g., reflectivity) describe generic material properties, while those ending in "-ance" (e.g., reflectance) apply to specific samples under defined conditions of spectral composition, polarization, and geometry.[11] This usage addresses real-world measurements that account for deviations from ideal behavior, such as scattering or absorption in non-ideal surfaces.[12] Reflectivity at a dielectric interface is fundamentally determined by the Fresnel reflection coefficient. For normal incidence, the amplitude reflection coefficient is where and are the refractive indices of the incident and second medium, respectively; the corresponding power reflectivity is then .[13] For a glass-air interface (, ), this yields at normal incidence, representing the ideal single-interface reflectivity.[14] Measured reflectance for an actual glass plate, however, would be higher due to contributions from both air-glass interfaces and partial internal reflections.[15] Standards like ISO 80000-7 define reflectance within radiometric quantities as the ratio of reflected to incident radiant power or flux, emphasizing its role in light and radiation measurements.[16] The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), in its Gold Book, equates reflectivity with reflectance, describing both as the fraction of incident radiation reflected by a surface or discontinuity.[17]Mathematical Formulations

Hemispherical Reflectance

Hemispherical reflectance, also known as hemispherical-hemispherical reflectance, is defined as the ratio of the total radiant flux reflected by a surface to the total radiant flux incident upon it from all directions within the hemisphere above the surface, assuming diffuse or integrated illumination over that hemisphere.[18][19] This quantity is dimensionless, as both fluxes are measured in watts (SI unit for radiant power), and it represents the overall reflective efficiency of a surface under broad, uniform incident light.[19] The key equation for hemispherical reflectance is given by where is the total reflected radiant flux and is the total incident radiant flux.[19] This formulation assumes uniform illumination across the incident hemisphere, and for ideal conservative surfaces that do not absorb energy, has an upper limit of 1, meaning all incident flux is reflected without loss.[18] The derivation of hemispherical reflectance involves integrating the reflected radiant power over the entire reflected hemisphere, which spans a solid angle steradians. Specifically, the total reflected flux is obtained by integrating the reflected radiance weighted by the cosine of the polar angle and the differential solid angle: , normalized by the incident flux to yield . This integration accounts for the projection of reflected light across all outgoing directions, providing a comprehensive measure for surfaces under isotropic incident conditions. In applications such as solar energy systems, hemispherical reflectance is crucial for assessing the performance of reflective surfaces in concentrating solar power (CSP) collectors, where it directly influences the efficiency of redirecting sunlight to receivers.[20] For example, typical white paints used in solar reflectors exhibit hemispherical reflectance values of 0.8 to 0.9 across visible and near-infrared wavelengths, enabling high energy capture while minimizing absorption.[21]Directional-Hemispherical Reflectance

Directional-hemispherical reflectance, denoted as , is defined as the ratio of the radiant flux reflected by an opaque surface into the entire outgoing hemisphere to the radiant flux incident on the surface from a specific direction specified by polar angle and azimuthal angle , assuming a collimated or directional beam illumination.[7] This measure captures the total reflected energy for a given incident direction, integrating over all possible reflection directions in the hemisphere above the surface.[7] The quantity is mathematically formulated in terms of radiance as where is the incident radiance from direction , is the reflected radiance in direction , normalizes for the projected incident area, accounts for the projected reflected area, and the integral is over the reflected solid angle hemisphere .[7] It relates directly to the bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF), , through since the reflected radiance follows .[7] This integration of the BRDF over the reflection hemisphere provides a directional analog to broader reflectance metrics, emphasizing angle-specific surface response without deriving the full BRDF here.[7] The value of varies with the incident angles, depending on the material's scattering properties, and is bounded between 0 and 1 to satisfy energy conservation, with a maximum of 1 for perfectly reflecting surfaces.[7] For specular surfaces, it remains near 1 across incident directions, though the reflected flux distribution peaks sharply at the specular reflection angle, concentrating energy in a narrow lobe.[7] In remote sensing, directional-hemispherical reflectance is essential for modeling the albedo of terrestrial surfaces as viewed by satellites under specific solar illumination geometries.[22]Spectral Reflectance

Spectral reflectance describes the fraction of incident radiant flux that is reflected from a surface as a function of wavelength or frequency , providing a wavelength-resolved measure essential for characterizing colored or dispersive materials where reflection properties vary across the electromagnetic spectrum.[23] This spectral dependence arises from material-specific interactions, such as absorption by electronic transitions in the visible range or scattering in the infrared, enabling precise optical analysis in fields like remote sensing and material science.[24] The spectral hemispherical reflectance, which integrates reflections over the entire outgoing hemisphere, is defined as where is the spectral reflected radiant flux and is the spectral incident radiant flux at wavelength .[19] Similarly, the spectral directional-hemispherical reflectance accounts for incident direction and integrates over the reflection hemisphere: where is the incident spectral radiance from direction , is the reflected spectral radiance in direction , normalizes for the projected incident area, accounts for the projected reflected area, and the integral is over the reflected hemisphere sr.[7] It relates to the spectral bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF), , through since the reflected spectral radiance follows .[7] These formulations use the subscript for per-unit-wavelength quantities; equivalent expressions apply using frequency for per-unit-frequency measures.[19] Broadband or total reflectance can be derived from spectral reflectance by integrating over the spectrum weighted by the incident light source: where represents the spectral power distribution of the source illumination.[19] This integration is crucial for applications like color rendering, where the perceived reflectance depends on both material properties and lighting conditions.[19] Spectral reflectance reveals material-specific behaviors, such as the high near-infrared reflectance of vegetation, typically ranging from 0.5 to 0.8 in the 0.7–1.1 m band, attributed to light scattering by the internal mesophyll cell structure of healthy leaves.[25] This contrast with low visible reflectance enables indices like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) in remote sensing, defined as NDVI = , to quantify vegetation density and health by exploiting spectral differences.[26] In metals, spectral variations are pronounced; for example, gold exhibits low reflectance in the ultraviolet (around 0.2–0.4) due to strong absorption but approaches near-unity reflectance (>0.95) in the infrared, stemming from free-electron behavior that enhances reflection at longer wavelengths.[27]Surface and Material Characteristics

Specular and Diffuse Reflectance

Specular reflectance occurs when light reflects from a smooth surface in a mirror-like manner, where the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection, producing a clear image of the source.[3] This behavior is characteristic of polished or flat interfaces, such as glass or metals, and is fundamentally described by the Fresnel equations, which quantify the fraction of incident light reflected based on the refractive indices of the materials and the angle of incidence.[28] For example, at normal incidence on glass (refractive index ≈1.5) in the visible spectrum, the reflectance is approximately 4%, increasing to around 10% at grazing angles near 60 degrees.[29] In contrast, diffuse reflectance arises from surfaces with microscopic roughness that scatter incident light in many directions, rather than concentrating it in a single specular direction, resulting in no distinct image formation.[30] Ideal diffuse reflectors, known as Lambertian surfaces, exhibit radiance that is independent of the viewing angle. The radiant intensity observed from the surface follows Lambert's cosine law: the intensity is proportional to the cosine of the angle between the surface normal and the line of sight, expressed as where is the intensity at normal incidence.[31] A representative example is matte paper, which achieves nearly uniform diffuse reflectance of about 0.8 across visible wavelengths, appearing equally bright from all angles due to this scattering.[32] Real surfaces often exhibit a transition between specular and diffuse behaviors, influenced by surface microstructure and roughness. Microfacet models treat the surface as composed of tiny mirror-like facets with varying orientations, where the overall reflectance is an average over these facets' contributions.[33] The seminal Torrance-Sparrow model, developed in 1967, incorporates a roughness parameter (the standard deviation of facet slope angles) to predict the broadening of the specular peak; as increases, the reflection shifts toward more diffuse scattering. For instance, a polished metal surface with low (e.g., <0.1 radians) shows predominantly specular reflectance exceeding 70% in the specular direction, while higher roughness values produce intermediate effects blending both components.[32]Reflectance of Liquids and Water

The reflectance of liquids, including water, primarily occurs at the air-liquid interface and is governed by the Fresnel equations, which describe the fraction of incident light reflected based on the refractive index and angle of incidence.[34] For smooth liquid surfaces, this reflection is specular, akin to principles observed in polished solids, but it is dynamically altered by fluid motion and surface perturbations.[35] In calm conditions, the reflectance of water in the visible spectrum ranges from approximately 0.02 at normal incidence to 0.1 at steeper angles, due to its refractive index of 1.33. Water exhibits particularly low surface reflectance compared to many materials, with about 2% at normal incidence arising from the modest refractive index contrast with air, though hemispherical reflectance under diffuse illumination averages around 5%.[36] Spectral variation is minimal across the visible wavelengths (400–700 nm), maintaining near-constant low values, but reflectance increases in the infrared due to higher absorption. On wind-roughened surfaces, capillary waves and larger undulations scatter light, elevating the diffuse reflectance component to up to 0.2, depending on wind speed.[37] To account for these effects, the effective reflectance is modeled as the sum of the Fresnel term for the mean interface and an additional scattering term from capillary waves:where is the specular reflection for a flat surface, and integrates contributions from wave slopes.[38] This formulation correlates with wind speed via models like Cox-Munk, which statistically distribute surface slopes (e.g., Gaussian for low winds, increasing variance with speed up to 10 m/s), enabling predictions of enhanced backscattering. In ocean color remote sensing, such adjustments correct for surface reflectance to isolate water-leaving radiance, facilitating chlorophyll detection by revealing subsurface absorption features around 443 nm.[39] A distinctive feature for water is Brewster's angle, approximately 53° from the normal, where p-polarized (parallel) reflectance drops to zero, as the reflected and refracted rays become perpendicular, eliminating reflection for that polarization.[40] This polarization selectivity is exploited in applications like glint reduction in remote sensing.[41]

Specialized Contexts

Grating Efficiency

In the context of diffraction gratings, grating efficiency generalizes the concept of reflectance to periodic structures, representing the fraction of incident optical power that is reflected into a specific diffraction order rather than a simple total reflection. This efficiency, denoted as for the -th order, is defined as , where is the power diffracted into order and is the incident power.[42] The angular positions of these diffracted orders are determined by the grating equation, , where is the angle of incidence, is the diffraction angle for order , is the wavelength, and is the grating groove spacing.[43] This framework applies particularly to reflection gratings, where light is reflected and dispersed into multiple orders, contrasting with transmission gratings that allow light to pass through the structure. Blazed gratings, a common type of reflection grating, feature asymmetric groove profiles (often sawtooth-shaped) designed to concentrate diffracted power into a single desired order, typically the first order (), achieving efficiencies of 70-90% under optimal conditions. These gratings outperform non-blazed designs by mimicking a specular reflection from the sloped facet of each groove, thereby enhancing energy transfer to the target order while minimizing losses to other orders or zero-order reflection. In contrast, transmission gratings distribute efficiency across orders more evenly but are less common in high-efficiency reflective applications due to material absorption constraints.[44] Grating efficiency is inherently polarization-dependent, with transverse electric (TE, or s-polarization) modes often exhibiting higher efficiency than transverse magnetic (TM, or p-polarization) modes, especially at oblique incidence angles common in spectroscopic setups. This dependence arises from the interaction of the electric field with the grating's periodic microstructure.[42] Reflection gratings with high efficiency are essential in spectrometers, where they enable precise wavelength dispersion for applications ranging from astronomical observations to laser spectroscopy. A notable example is the echelle grating, which operates in high orders (e.g., ) to provide exceptional spectral resolution (often >10,000) over broad bandwidths, with efficiencies maintained above 50% despite the high-order operation, making it ideal for high-throughput instruments.[45]Related Radiometric Coefficients

In radiometry, reflectance is interconnected with other coefficients that describe the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter, providing a complete accounting of incident energy. These include absorptance, transmittance, and emissivity, which together obey conservation principles for energy balance.[46][47] Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation states that, for an opaque body in thermal equilibrium, the emissivity ε equals the absorptance α, and both are related to reflectance ρ by ε = α = 1 - ρ at each wavelength.[48][49] This law ensures detailed balance between emission and absorption processes.[50] Absorptance α is defined as the ratio of absorbed radiant flux Φ_e^a to incident radiant flux Φ_e^i, given by α = Φ_e^a / Φ_e^i.[46][47] Transmittance τ, relevant for transparent or semi-transparent media, is the ratio of transmitted radiant flux Φ_e^t to incident flux, τ = Φ_e^t / Φ_e^i.[46][47] For opaque materials where τ = 0, conservation requires ρ + α = 1.[19][50] The following table summarizes key radiometric coefficients related to reflectance, all of which are dimensionless ratios between 0 and 1:| Coefficient | Symbol | Definition | Key Relation | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reflectance | ρ | Reflected flux / incident flux | For opaque: ρ + α = 1 | Mirror: ρ ≈ 1, α ≈ 0 |

| Absorptance | α | Absorbed flux / incident flux | α = 1 - ρ (opaque) | Blackbody: α = 1, ρ = 0 |

| Transmittance | τ | Transmitted flux / incident flux | ρ + α + τ = 1 (non-scattering) | Clear glass: τ ≈ 0.9, ρ ≈ 0.08 |

| Emissivity | ε | Emitted flux / blackbody flux | ε = α (Kirchhoff's law) | Blackbody: ε = 1 |