Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Static single-assignment form

View on WikipediaIn compiler design, static single assignment form (often abbreviated as SSA form or simply SSA) is a type of intermediate representation (IR) where each variable is assigned exactly once. SSA is used in most high-quality optimizing compilers for imperative languages, including LLVM, the GNU Compiler Collection, and many commercial compilers.

There are efficient algorithms for converting programs into SSA form. To convert to SSA, existing variables in the original IR are split into versions, new variables typically indicated by the original name with a subscript, so that every definition gets its own version. Additional statements that assign to new versions of variables may also need to be introduced at the join point of two control flow paths. Converting from SSA form to machine code is also efficient.

SSA makes numerous analyses needed for optimizations easier to perform, such as determining use-define chains, because when looking at a use of a variable there is only one place where that variable may have received a value. Most optimizations can be adapted to preserve SSA form, so that one optimization can be performed after another with no additional analysis. The SSA based optimizations are usually more efficient and more powerful than their non-SSA form prior equivalents.

In functional language compilers, such as those for Scheme and ML, continuation-passing style (CPS) is generally used. SSA is formally equivalent to a well-behaved subset of CPS excluding non-local control flow, so optimizations and transformations formulated in terms of one generally apply to the other. Using CPS as the intermediate representation is more natural for higher-order functions and interprocedural analysis. CPS also easily encodes call/cc, whereas SSA does not.[1]

History

[edit]SSA was developed in the 1980s by several researchers at IBM. Kenneth Zadeck, a key member of the team, moved to Brown University as development continued.[2][3] A 1986 paper introduced birthpoints, identity assignments, and variable renaming such that variables had a single static assignment.[4] A subsequent 1987 paper by Jeanne Ferrante and Ronald Cytron[5] proved that the renaming done in the previous paper removes all false dependencies for scalars.[3] In 1988, Barry Rosen, Mark N. Wegman, and Kenneth Zadeck replaced the identity assignments with Φ-functions, introduced the name "static single-assignment form", and demonstrated a now-common SSA optimization.[6] The name Φ-function was chosen by Rosen to be a more publishable version of "phony function".[3] Alpern, Wegman, and Zadeck presented another optimization, but using the name "static single assignment".[7] Finally, in 1989, Rosen, Wegman, Zadeck, Cytron, and Ferrante found an efficient means of converting programs to SSA form.[8]

Benefits

[edit]The primary usefulness of SSA comes from how it simultaneously simplifies and improves the results of a variety of compiler optimizations, by simplifying the properties of variables. For example, consider this piece of code:

y := 1 y := 2 x := y

Humans can see that the first assignment is not necessary, and that the value of y being used in the third line comes from the second assignment of y. A program would have to perform reaching definition analysis to determine this. But if the program is in SSA form, both of these are immediate:

y1 := 1 y2 := 2 x1 := y2

Compiler optimization algorithms that are either enabled or strongly enhanced by the use of SSA include:

- Constant folding – conversion of computations from runtime to compile time, e.g. treat the instruction

a=3*4+5;as if it werea=17; - Value range propagation[9] – precompute the potential ranges a calculation could be, allowing for the creation of branch predictions in advance

- Sparse conditional constant propagation – range-check some values, allowing tests to predict the most likely branch

- Dead-code elimination – remove code that will have no effect on the results

- Global value numbering – replace duplicate calculations producing the same result

- Partial-redundancy elimination – removing duplicate calculations previously performed in some branches of the program

- Strength reduction – replacing expensive operations by less expensive but equivalent ones, e.g. replace integer multiply or divide by powers of 2 with the potentially less expensive shift left (for multiply) or shift right (for divide).

- Register allocation – optimize how the limited number of machine registers may be used for calculations

Converting to SSA

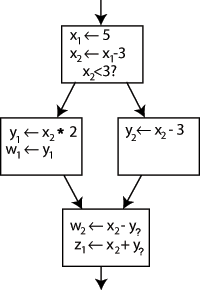

[edit]Converting ordinary code into SSA form is primarily a matter of replacing the target of each assignment with a new variable, and replacing each use of a variable with the "version" of the variable reaching that point. For example, consider the following control-flow graph:

Changing the name on the left hand side of "x x - 3" and changing the following uses of x to that new name would leave the program unaltered. This can be exploited in SSA by creating two new variables: x1 and x2, each of which is assigned only once. Likewise, giving distinguishing subscripts to all the other variables yields:

It is clear which definition each use is referring to, except for one case: both uses of y in the bottom block could be referring to either y1 or y2, depending on which path the control flow took.

To resolve this, a special statement is inserted in the last block, called a Φ (Phi) function. This statement will generate a new definition of y called y3 by "choosing" either y1 or y2, depending on the control flow in the past.

Now, the last block can simply use y3, and the correct value will be obtained either way. A Φ function for x is not needed: only one version of x, namely x2 is reaching this place, so there is no problem (in other words, Φ(x2,x2)=x2).

Given an arbitrary control-flow graph, it can be difficult to tell where to insert Φ functions, and for which variables. This general question has an efficient solution that can be computed using a concept called dominance frontiers (see below).

Φ functions are not implemented as machine operations on most machines. A compiler can implement a Φ function by inserting "move" operations at the end of every predecessor block. In the example above, the compiler might insert a move from y1 to y3 at the end of the middle-left block and a move from y2 to y3 at the end of the middle-right block. These move operations might not end up in the final code based on the compiler's register allocation procedure. However, this approach may not work when simultaneous operations are speculatively producing inputs to a Φ function, as can happen on wide-issue machines. Typically, a wide-issue machine has a selection instruction used in such situations by the compiler to implement the Φ function.

Computing minimal SSA using dominance frontiers

[edit]In a control-flow graph, a node A is said to strictly dominate a different node B if it is impossible to reach B without passing through A first. In other words, if node B is reached, then it can be assumed that A has run. A is said to dominate B (or B to be dominated by A) if either A strictly dominates B or A = B.

A node which transfers control to a node A is called an immediate predecessor of A.

The dominance frontier of node A is the set of nodes B where A does not strictly dominate B, but does dominate some immediate predecessor of B. These are the points at which multiple control paths merge back together into a single path.

For example, in the following code:

[1] x = random()

if x < 0.5

[2] result = "heads"

else

[3] result = "tails"

end

[4] print(result)

Node 1 strictly dominates 2, 3, and 4 and the immediate predecessors of node 4 are nodes 2 and 3.

Dominance frontiers define the points at which Φ functions are needed. In the above example, when control is passed to node 4, the definition of result used depends on whether control was passed from node 2 or 3. Φ functions are not needed for variables defined in a dominator, as there is only one possible definition that can apply.

There is an efficient algorithm for finding dominance frontiers of each node. This algorithm was originally described in "Efficiently Computing Static Single Assignment Form and the Control Graph" by Ron Cytron, Jeanne Ferrante, et al. in 1991.[10]

Keith D. Cooper, Timothy J. Harvey, and Ken Kennedy of Rice University describe an algorithm in their paper titled A Simple, Fast Dominance Algorithm:[11]

for each node b

dominance_frontier(b) := {}

for each node b

if the number of immediate predecessors of b ≥ 2

for each p in immediate predecessors of b

runner := p

while runner ≠ idom(b)

dominance_frontier(runner) := dominance_frontier(runner) ∪ { b }

runner := idom(runner)

In the code above, idom(b) is the immediate dominator of b, the unique node that strictly dominates b but does not strictly dominate any other node that strictly dominates b.

Variations that reduce the number of Φ functions

[edit]"Minimal" SSA inserts the minimal number of Φ functions required to ensure that each name is assigned a value exactly once and that each reference (use) of a name in the original program can still refer to a unique name. (The latter requirement is needed to ensure that the compiler can write down a name for each operand in each operation.)

However, some of these Φ functions could be dead. For this reason, minimal SSA does not necessarily produce the fewest Φ functions that are needed by a specific procedure. For some types of analysis, these Φ functions are superfluous and can cause the analysis to run less efficiently.

Pruned SSA

[edit]Pruned SSA form is based on a simple observation: Φ functions are only needed for variables that are "live" after the Φ function. (Here, "live" means that the value is used along some path that begins at the Φ function in question.) If a variable is not live, the result of the Φ function cannot be used and the assignment by the Φ function is dead.

Construction of pruned SSA form uses live-variable information in the Φ function insertion phase to decide whether a given Φ function is needed. If the original variable name isn't live at the Φ function insertion point, the Φ function isn't inserted.

Another possibility is to treat pruning as a dead-code elimination problem. Then, a Φ function is live only if any use in the input program will be rewritten to it, or if it will be used as an argument in another Φ function. When entering SSA form, each use is rewritten to the nearest definition that dominates it. A Φ function will then be considered live as long as it is the nearest definition that dominates at least one use, or at least one argument of a live Φ.

Semi-pruned SSA

[edit]Semi-pruned SSA form[12] is an attempt to reduce the number of Φ functions without incurring the relatively high cost of computing live-variable information. It is based on the following observation: if a variable is never live upon entry into a basic block, it never needs a Φ function. During SSA construction, Φ functions for any "block-local" variables are omitted.

Computing the set of block-local variables is a simpler and faster procedure than full live-variable analysis, making semi-pruned SSA form more efficient to compute than pruned SSA form. On the other hand, semi-pruned SSA form will contain more Φ functions.

Block arguments

[edit]Block arguments are an alternative to Φ functions that is representationally identical but in practice can be more convenient during optimization. Blocks are named and take a list of block arguments, notated as function parameters. When calling a block the block arguments are bound to specified values. MLton, Swift SIL, and LLVM MLIR use block arguments.[13]

Converting out of SSA form

[edit]SSA form is not normally used for direct execution (although it is possible to interpret SSA[14]), and it is frequently used "on top of" another IR with which it remains in direct correspondence. This can be accomplished by "constructing" SSA as a set of functions that map between parts of the existing IR (basic blocks, instructions, operands, etc.) and its SSA counterpart. When the SSA form is no longer needed, these mapping functions may be discarded, leaving only the now-optimized IR.

Performing optimizations on SSA form usually leads to entangled SSA-Webs, meaning there are Φ instructions whose operands do not all have the same root operand. In such cases color-out algorithms are used to come out of SSA. Naive algorithms introduce a copy along each predecessor path that caused a source of different root symbol to be put in Φ than the destination of Φ. There are multiple algorithms for coming out of SSA with fewer copies, most use interference graphs or some approximation of it to do copy coalescing.[15]

Extensions

[edit]Extensions to SSA form can be divided into two categories.

Renaming scheme extensions alter the renaming criterion. Recall that SSA form renames each variable when it is assigned a value. Alternative schemes include static single use form (which renames each variable at each statement when it is used) and static single information form (which renames each variable when it is assigned a value, and at the post-dominance frontier).

Feature-specific extensions retain the single assignment property for variables, but incorporate new semantics to model additional features. Some feature-specific extensions model high-level programming language features like arrays, objects and aliased pointers. Other feature-specific extensions model low-level architectural features like speculation and predication.

Compilers using SSA form

[edit]Open-source

[edit]- Mono uses SSA in its JIT compiler called Mini

- WebKit uses SSA in its JIT compilers.[16][17]

- Swift defines its own SSA form above LLVM IR, called SIL (Swift Intermediate Language).[18][19]

- The Erlang compiler was rewritten in OTP 22.0 to "internally use an intermediate representation based on Static Single Assignment (SSA)", with plans for further optimizations built on top of SSA in future releases.[20]

- The LLVM Compiler Infrastructure uses SSA form for all scalar register values (everything except memory) in its primary code representation. SSA form is only eliminated once register allocation occurs, late in the compile process (often at link time).

- The GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) makes extensive use of SSA since version 4 (released in April 2005). The frontends generate "GENERIC" code that is then converted into "GIMPLE" code by the "gimplifier". High-level optimizations are then applied on the SSA form of "GIMPLE". The resulting optimized intermediate code is then translated into RTL, on which low-level optimizations are applied. The architecture-specific backends finally turn RTL into assembly language.

- Go (1.7: for x86-64 architecture only; 1.8: for all supported architectures).[21][22]

- IBM's open source adaptive Java virtual machine, Jikes RVM, uses extended Array SSA, an extension of SSA that allows analysis of scalars, arrays, and object fields in a unified framework. Extended Array SSA analysis is only enabled at the maximum optimization level, which is applied to the most frequently executed portions of code.

- The Mozilla Firefox SpiderMonkey JavaScript engine uses SSA-based IR.[23]

- The Chromium V8 JavaScript engine implements SSA in its Crankshaft compiler infrastructure as announced in December 2010

- PyPy uses a linear SSA representation for traces in its JIT compiler.

- The Android Runtime[24] and the Dalvik Virtual Machine use SSA.[25]

- The Standard ML compiler MLton uses SSA in one of its intermediate languages.

- LuaJIT makes heavy use of SSA-based optimizations.[26]

- The PHP and Hack compiler HHVM uses SSA in its IR.[27]

- The OCaml compiler uses SSA in its CMM IR (which stands for C--).[28]

- libFirm, a library for use as the middle and back ends of a compiler, uses SSA form for all scalar register values until code generation by use of an SSA-aware register allocator.[29]

- Various Mesa drivers via NIR, an SSA representation for shading languages.[30]

Commercial

[edit]- Oracle's HotSpot Java Virtual Machine uses an SSA-based intermediate language in its JIT compiler.[31]

- Microsoft Visual C++ compiler backend available in Microsoft Visual Studio 2015 Update 3 uses SSA[32]

- SPIR-V, the shading language standard for the Vulkan graphics API and kernel language for OpenCL compute API, is an SSA representation.[33]

- The IBM family of XL compilers, which include C, C++ and Fortran.[34]

- NVIDIA CUDA[35]

Research and abandoned

[edit]- The ETH Oberon-2 compiler was one of the first public projects to incorporate "GSA", a variant of SSA.

- The Open64 compiler used SSA form in its global scalar optimizer, though the code is brought into SSA form before and taken out of SSA form afterwards. Open64 uses extensions to SSA form to represent memory in SSA form as well as scalar values.

- In 2002, researchers modified IBM's JikesRVM (named Jalapeño at the time) to run both standard Java bytecode and a typesafe SSA (SafeTSA) bytecode class files, and demonstrated significant performance benefits to using the SSA bytecode.

- jackcc is an open-source compiler for the academic instruction set Jackal 3.0. It uses a simple 3-operand code with SSA for its intermediate representation. As an interesting variant, it replaces Φ functions with a so-called SAME instruction, which instructs the register allocator to place the two live ranges into the same physical register.

- The Illinois Concert Compiler circa 1994[36] used a variant of SSA called SSU (Static Single Use) which renames each variable when it is assigned a value, and in each conditional context in which that variable is used; essentially the static single information form mentioned above. The SSU form is documented in John Plevyak's Ph.D Thesis.

- The COINS compiler uses SSA form optimizations as explained here.

- Reservoir Labs' R-Stream compiler supports non-SSA (quad list), SSA and SSI (Static Single Information[37]) forms.[38]

- Although not a compiler, the Boomerang decompiler uses SSA form in its internal representation. SSA is used to simplify expression propagation, identifying parameters and returns, preservation analysis, and more.

- DotGNU Portable.NET used SSA in its JIT compiler.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Kelsey, Richard A. (1995). "A correspondence between continuation passing style and static single assignment form" (PDF). Papers from the 1995 ACM SIGPLAN workshop on Intermediate representations. pp. 13–22. doi:10.1145/202529.202532. ISBN 0897917545. S2CID 6207179.

- ^ Rastello & Tichadou 2022, sec. 1.4.

- ^ a b c Zadeck, Kenneth (April 2009). The Development of Static Single Assignment Form (PDF). Static Single-Assignment Form Seminar. Autrans, France.

- ^ Cytron, Ron; Lowry, Andy; Zadeck, F. Kenneth (1986). "Code motion of control structures in high-level languages". Proceedings of the 13th ACM SIGACT-SIGPLAN symposium on Principles of programming languages - POPL '86. pp. 70–85. doi:10.1145/512644.512651. S2CID 9099471.

- ^ Cytron, Ronald Kaplan; Ferrante, Jeanne. What's in a name? Or, the value of renaming for parallelism detection and storage allocation. International Conference on Parallel Processing, ICPP'87 1987. pp. 19–27.

- ^ Barry Rosen; Mark N. Wegman; F. Kenneth Zadeck (1988). "Global value numbers and redundant computations" (PDF). Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages - POPL '88. pp. 12–27. doi:10.1145/73560.73562. ISBN 0-89791-252-7.

- ^ Alpern, B.; Wegman, M. N.; Zadeck, F. K. (1988). "Detecting equality of variables in programs". Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages - POPL '88. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1145/73560.73561. ISBN 0897912527. S2CID 18384941.

- ^ Cytron, Ron; Ferrante, Jeanne; Rosen, Barry K.; Wegman, Mark N. & Zadeck, F. Kenneth (1991). "Efficiently computing static single assignment form and the control dependence graph" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 13 (4): 451–490. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.100.6361. doi:10.1145/115372.115320. S2CID 13243943.

- ^ value range propagation

- ^ Cytron, Ron; Ferrante, Jeanne; Rosen, Barry K.; Wegman, Mark N.; Zadeck, F. Kenneth (1 October 1991). "Efficiently computing static single assignment form and the control dependence graph". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 13 (4): 451–490. doi:10.1145/115372.115320. S2CID 13243943.

- ^ Cooper, Keith D.; Harvey, Timothy J.; Kennedy, Ken (2001). A Simple, Fast Dominance Algorithm (PDF) (Technical report). Rice University, CS Technical Report 06-33870. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-26.

- ^ Briggs, Preston; Cooper, Keith D.; Harvey, Timothy J.; Simpson, L. Taylor (1998). Practical Improvements to the Construction and Destruction of Static Single Assignment Form (PDF) (Technical report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-07.

- ^ "Block Arguments vs PHI nodes - MLIR Rationale". mlir.llvm.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ von Ronne, Jeffery; Ning Wang; Michael Franz (2004). "Interpreting programs in static single assignment form". Proceedings of the 2004 workshop on Interpreters, virtual machines and emulators - IVME '04. p. 23. doi:10.1145/1059579.1059585. ISBN 1581139098. S2CID 451410.

- ^ Boissinot, Benoit; Darte, Alain; Rastello, Fabrice; Dinechin, Benoît Dupont de; Guillon, Christophe (2008). "Revisiting Out-of-SSA Translation for Correctness, Code Quality, and Efficiency". HAL-Inria Cs.DS: 14.

- ^ "Introducing the WebKit FTL JIT". 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Introducing the B3 JIT Compiler". 15 February 2016.

- ^ "Swift Intermediate Language (GitHub)". GitHub. 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Swift's High-Level IR: A Case Study of Complementing LLVM IR with Language-Specific Optimization, LLVM Developers Meetup 10/2015". YouTube. 9 November 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ^ "OTP 22.0 Release Notes".

- ^ "Go 1.7 Release Notes - The Go Programming Language". golang.org. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ "Go 1.8 Release Notes - The Go Programming Language". golang.org. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- ^ "IonMonkey Overview".,

- ^ The Evolution of ART - Google I/O 2016. Google. 25 May 2016. Event occurs at 3m47s.

- ^ Ramanan, Neeraja (12 Dec 2011). "JIT through the ages" (PDF).

- ^ "Bytecode Optimizations". the LuaJIT project.

- ^ "HipHop Intermediate Representation (HHIR)". GitHub. 30 October 2021.

- ^ Chambart, Pierre; Laviron, Vincent; Pinto, Dario (2024-03-18). "Behind the Scenes of the OCaml Optimising Compiler". OCaml Pro.

- ^ "Firm - Optimization and Machine Code Generation".

- ^ Ekstrand, Jason (16 December 2014). "Reintroducing NIR, a new IR for mesa".

- ^ "The Java HotSpot Performance Engine Architecture". Oracle Corporation.

- ^ "Introducing a new, advanced Visual C++ code optimizer". 4 May 2016.

- ^ "SPIR-V spec" (PDF).

- ^ Sarkar, V. (May 1997). "Automatic selection of high-order transformations in the IBM XL FORTRAN compilers" (PDF). IBM Journal of Research and Development. 41 (3). IBM: 233–264. doi:10.1147/rd.413.0233.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Gautam; Grover, Vinod; Aarts, Bastiaan; Kong, Xiangyun; Kudlur, Manjunath; Lin, Yuan; Marathe, Jaydeep; Murphy, Mike; Wang, Jian-Zhong (2012). "CUDA: Compiling and optimizing for a GPU platform". Procedia Computer Science. 9: 1910–1919. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2012.04.209.

- ^ "Illinois Concert Project". Archived from the original on 2014-03-13.

- ^ Ananian, C. Scott; Rinard, Martin (1999). Static Single Information Form (PDF) (Technical report). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1.9976.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Parallel Computing.

General references

[edit]- Rastello, Fabrice; Tichadou, Florent Bouchez, eds. (2022). SSA-based compiler design (PDF). Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-80515-9. ISBN 978-3-030-80515-9. S2CID 63274602.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Appel, Andrew W. (1999). Modern Compiler Implementation in ML. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58274-2. Also available in Java (ISBN 0-521-82060-X, 2002) and C (ISBN 0-521-60765-5, 1998) versions.

- Cooper, Keith D. & Torczon, Linda (2003). Engineering a Compiler. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1-55860-698-2.

- Muchnick, Steven S. (1997). Advanced Compiler Design and Implementation. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-1-55860-320-2.

- Kelsey, Richard A. (March 1995). "A Correspondence between Continuation Passing Style and Static Single Assignment Form". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 30 (3): 13–22. doi:10.1145/202530.202532.

- Appel, Andrew W. (April 1998). "SSA is Functional Programming". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 33 (4): 17–20. doi:10.1145/278283.278285. S2CID 207227209.

- Pop, Sebastian (2006). "The SSA Representation Framework: Semantics, Analyses and GCC Implementation" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Matthias Braun; Sebastian Buchwald; Sebastian Hack; Roland Leißa; Christoph Mallon; Andreas Zwinkau (2013), "Simple and Efficient Construction of Static Single Assignment Form", Compiler Construction, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 7791, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 102–122, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-37051-9_6, ISBN 978-3-642-37050-2, retrieved 24 March 2013

External links

[edit]- Bosscher, Steven; and Novillo, Diego. GCC gets a new Optimizer Framework. An article about GCC's use of SSA and how it improves over older IRs.

- The SSA Bibliography. Extensive catalogue of SSA research papers.

- Zadeck, F. Kenneth. "The Development of Static Single Assignment Form", December 2007 talk on the origins of SSA.

Static single-assignment form

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition and Motivation

Static single-assignment (SSA) form is an intermediate representation (IR) in compiler design where each variable is assigned a value exactly once in the program, and subsequent uses of that variable refer to this unique definition.[1] To handle control flow merges, such as at join points in the program's control flow graph, SSA introduces special φ-functions that select the appropriate value from incoming paths based on execution history.[1] This renaming of variables—typically subscripted to distinguish definitions, like and —ensures that every use unambiguously traces back to its single static assignment point.[1] The primary motivation for SSA form arises from its ability to simplify data-flow analysis in compilers, where traditional representations complicate tracking variable definitions and uses due to reassignments.[1] By eliminating multiple assignments to the same variable, SSA makes the computation of reaching definitions and live variables straightforward and efficient, often reducible to linear-time algorithms over the control flow graph.[1] This structure facilitates optimizations such as constant propagation, dead code elimination, and partial redundancy elimination by exposing def-use chains explicitly without the overhead of implicit flow dependencies.[1] In contrast to traditional three-address code, where a variable like might be reassigned multiple times—creating anti-dependencies and output dependencies that obscure analysis—SSA avoids these issues by assigning distinct names to each definition, thus decoupling true data dependencies from storage reuse.[1] For example, consider this non-SSA pseudocode snippet with reassignment:if (cond) {

x = a + b;

} else {

x = c + d;

}

y = x * 2;

if (cond) {

x = a + b;

} else {

x = c + d;

}

y = x * 2;

if (cond) {

x1 = a + b;

} else {

x2 = c + d;

}

x3 = φ(x1, x2); // Selects based on path

y = x3 * 2;

if (cond) {

x1 = a + b;

} else {

x2 = c + d;

}

x3 = φ(x1, x2); // Selects based on path

y = x3 * 2;

Basic Representation and Phi Functions

In static single-assignment (SSA) form, the basic representation transforms a program's intermediate representation such that each variable is assigned a value exactly once, ensuring that every use of a variable is preceded by and dominated by its unique definition.[4] This is achieved by renaming variables at each assignment site: for instance, successive assignments to a variable x become x₁ = ..., x₂ = ..., and so on, with all subsequent uses updated to reference the appropriate renamed version based on the control flow path.[4] No variable is ever redefined after its initial assignment, which eliminates the need to track multiple possible definitions during analysis.[4] To handle control flow where multiple paths may reach a point with different versions of a variable, SSA introduces phi functions (φ-functions) at convergence points in the control-flow graph (CFG).[4] A phi function has the syntax , where are the renamed variables from the predecessor basic blocks, and it selects the value from the predecessor block that actually transfers control to the current block.[4] These functions are placed at the entry of basic blocks where control paths merge, such as after conditional branches or loops, ensuring the single-assignment property holds even in the presence of unstructured control flow.[4] In the context of a CFG, which models the program as a directed graph with nodes representing basic blocks and edges indicating possible control transfers, phi functions are inserted precisely at nodes that serve as join points for incoming edges.[4] The arguments of a phi function correspond directly to these incoming edges, with the -th argument linked to the -th predecessor, thereby explicitly representing the merging of values without altering the underlying control structure.[4] This notation facilitates precise data-flow tracking, as the phi function's result becomes a new renamed variable that dominates all subsequent uses in the block.[4]Illustrative Example

To illustrate the transformation to static single-assignment (SSA) form, consider a simple program with an if-then-else structure that conditionally assigns a value to a variableV and then uses it in a subsequent computation.[4]

The original non-SSA code is as follows:

if (P) then

V = 4

else

V = 6

V = V + 5

*use(V)*

if (P) then

V = 4

else

V = 6

V = V + 5

*use(V)*

P is a condition, and the final *use(V)* represents any statement consuming V, such as printing or further computation. This code has a control flow graph (CFG) with three basic blocks: an entry block leading to the conditional branch, a then-block assigning V = 4, an else-block assigning V = 6, and a merge block after the branch where V = V + 5 occurs. The merge block is a join point where paths from the then- and else-blocks converge.[4]

The conversion to SSA form proceeds in steps, renaming variables to ensure each is assigned exactly once and inserting φ-functions at merge points to select the appropriate value based on the incoming control path.

-

Rename definitions along each path: In the then-branch, the assignment becomes

V_1 = 4. In the else-branch, it becomesV_2 = 6. These subscripts distinguish the unique static assignments. -

Propagate renamed uses: In the merge block, the use of

VinV = V + 5now requires the value from the appropriate predecessor path, so a φ-function is inserted at the start of the merge block:V_3 = φ(V_1, V_2). The assignment then updates toV_4 = V_3 + 5, and the final use becomes*use(V_4)*.

if (P) then

V_1 = 4

else

V_2 = 6

V_3 = φ(V_1, V_2)

V_4 = V_3 + 5

*use(V_4)*

if (P) then

V_1 = 4

else

V_2 = 6

V_3 = φ(V_1, V_2)

V_4 = V_3 + 5

*use(V_4)*

V_1 (then-path) and V_2 (else-path), explicitly modeling the data flow selection without implicit aliasing. A simplified textual representation of the augmented CFG is:

Entry

|

v

Cond (P)

/ \

v v

Then Else

(V_1=4) (V_2=6)

\ /

v v

Merge: V_3 = φ(V_1, V_2)

V_4 = V_3 + 5

*use(V_4)*

Entry

|

v

Cond (P)

/ \

v v

Then Else

(V_1=4) (V_2=6)

\ /

v v

Merge: V_3 = φ(V_1, V_2)

V_4 = V_3 + 5

*use(V_4)*

P is known, V_3 can be simplified directly).[4]

Historical Development

Origins and Key Publications

The invention of static single-assignment (SSA) form is credited to Ron Cytron, Jeanne Ferrante, Barry K. Rosen, Mark N. Wegman, and F. Kenneth Zadeck, who developed it between 1988 and 1990 while working at IBM's T.J. Watson Research Center and Brown University.[5] This representation emerged as a way to restructure intermediate code for more effective data flow analysis in optimizing compilers.[4] The initial public presentation of SSA form occurred in the 1989 paper "An Efficient Method of Computing Static Single Assignment Form," delivered at the 16th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages (POPL).[5] This work introduced an algorithm for constructing SSA form efficiently, even for programs with arbitrary control flow. A comprehensive follow-up publication, "Efficiently Computing Static Single Assignment Form and the Control Dependence Graph," appeared in ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems (TOPLAS) in 1991, expanding on the construction methods and linking SSA to control dependence analysis.[4] Early development of SSA was driven by the demands of parallelization and optimization for supercomputers, particularly within IBM's PTRAN project, which focused on automatically restructuring sequential Fortran programs for multiprocessor architectures.[5] Related precursor concepts, such as value numbering—a technique for identifying equivalent expressions across program points to enable common subexpression elimination—provided foundational ideas for tracking variable values, though SSA uniquely enforced a single static assignment per variable to streamline optimizations like code motion and constant propagation.[6]Evolution in Compiler Design

During the 1990s, the introduction of sparse static single-assignment (SSA) form marked a significant milestone in compiler design, enabling more efficient representations by placing phi functions only at dominance frontiers rather than at every merge point. This approach, detailed in the seminal work by Cytron et al., reduced the overhead of SSA construction and made it viable for practical use in optimizing compilers.[1] Additionally, handling of loops was refined through phi insertions at loop headers to capture variable versions across iterations, while extensions like the Static Single Information (SSI) form addressed challenges with exceptions and predicated execution by introducing parameter passing at entry points.[1][7] Adoption of SSA in major compilers began in the late 1990s and accelerated into the 2000s, with limited experimental integration in the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) leading to its full incorporation as Tree SSA in version 4.0 released in 2005.[8] This framework transformed GCC's middle-end optimizations by leveraging SSA for data-flow analyses. Concurrently, SSA profoundly influenced the development of the LLVM compiler infrastructure, initiated in 2000 at the University of Illinois, where it was adopted as the foundational property of the intermediate representation (IR) from the outset to facilitate type-safe, optimizable code generation.[9] Over time, SSA evolved from a temporary transformation applied during specific optimization phases to a core component of the IR in modern compilers, enabling persistent use throughout the compilation pipeline for improved analysis precision and transformation simplicity. In LLVM and GCC, this shift has allowed optimizations like constant propagation and dead code elimination to operate directly on SSA without repeated conversions, enhancing overall compiler performance.[10] In recent trends up to 2025, SSA has been widely adopted in just-in-time (JIT) compilers for dynamic languages, such as V8's TurboFan and Maglev compilers and GraalVM's compiler, which employ graph-based SSA forms (often in a sea-of-nodes style) to enable adaptive optimizations for runtime-generated code.[11][12] Frameworks like LLVM also leverage SSA as a core element of their IR. A notable advancement is the Multi-Level Intermediate Representation (MLIR), introduced in 2019 as part of the LLVM project, which embeds SSA as its core formalism while providing dialect support to model domain-specific abstractions—such as tensor operations or control flow—maintaining SSA properties across progressive lowerings to machine code. This dialect mechanism addresses limitations in traditional SSA by enabling composable, multi-abstraction IRs tailored for heterogeneous computing and JIT scenarios in dynamic environments.[13]Construction Methods

Dominance and Dominance Frontiers

In control-flow graphs (CFGs), a fundamental prerequisite for constructing static single-assignment (SSA) form is the concept of dominance, which captures the necessary control-flow paths for variable definitions. A node dominates a node in a CFG if every path from the entry node to passes through ; this relation is reflexive and transitive.[1] Strict dominance, denoted , holds when dominates and .[1] The immediate dominator of , written , is the strict dominator of that is closest to in the dominance relation, forming the basis for the dominator tree.[1] Dominance frontiers identify the points in the CFG where dominance relations "break," which is crucial for placing -functions in SSA form. The dominance frontier of a node , denoted , is the set of nodes such that there exists a predecessor of where strictly dominates but does not dominate : This set captures the merge points where control flow from -dominated regions converges without dominating the merge.[1] To compute dominators, standard methods rely on data-flow analysis over the CFG. The simple iterative algorithm initializes dominators for each node as the universal set, then iteratively computes until convergence, achieving time complexity in the worst case, where is nodes.[1] For efficiency, the Lengauer-Tarjan algorithm uses depth-first search numbering and link-eval operations on a forest to compute immediate dominators in nearly linear time, specifically , and constructs the dominator tree by linking each node to its immediate dominator. Once dominators are known, dominance frontiers can be computed via a bottom-up traversal of the dominator tree: first, compute local frontiers , then propagate upwards with , yielding , in time.[1] Post-dominators extend dominance symmetrically from the exit node, where a node post-dominates if every path from to the exit passes through ; this is relevant for handling exceptional exits or structured control flow in SSA construction.[1] The post-dominator tree mirrors the dominator tree but is rooted at the exit, aiding in analyses like control dependence.[1]Minimal SSA Computation Algorithm

The minimal static single-assignment (SSA) form computation algorithm, as introduced by Cytron et al., transforms a program's control-flow graph into SSA form by inserting the minimal number of phi functions necessary to resolve variable definitions reaching join points, ensuring each variable is assigned exactly once while preserving the original semantics.[4] This approach avoids extraneous phi functions at non-frontier nodes, distinguishing minimal SSA from more permissive forms that may insert redundant merges.[4] The algorithm operates on arbitrary control-flow graphs, including unstructured code with arbitrary gotos, by relying on dominance relations to guide insertions.[4] The algorithm proceeds in four main steps. First, it computes the dominance relation for all nodes in the control-flow graph, identifying for each node the set of nodes that strictly dominate it (i.e., appear on every path from the entry node to ). This step can be performed efficiently using algorithms such as Lengauer and Tarjan's near-linear time method, achieving complexity where is the number of edges and is the number of nodes and is the inverse Ackermann function, though simpler iterative data-flow analyses yield in the worst case.[4] Second, it calculates the iterated dominance frontiers for each node, which are the points where control paths merge and a variable defined in one path may reach the merge without being redefined; dominance frontiers, as previously defined, form the basis for these iterated sets by propagating frontiers upward through the dominator tree.[4] Third, phi functions are placed at the iterated dominance frontiers of each original variable definition site. For each variable with definition nodes , the algorithm initializes a worklist with and iteratively adds nodes in the dominance frontier of any node in the worklist until saturation, inserting a phi function for at each such frontier node if it has multiple predecessors. This ensures phi nodes appear only where necessary to merge incoming values, with the process running in time proportional to the total number of assignments times the average dominance frontier size, typically linear in practice.[4] Finally, variable renaming is performed using a stack-based approach during a depth-first traversal of the control-flow graph to assign unique SSA names. Each original variable maintains a stack of its SSA versions; uses are replaced with the current top-of-stack version, new versions are pushed for definitions (including phi results), and stacks are popped upon completing the scope of definitions. Phi function arguments are specially handled by assigning the version that was live-out from each predecessor block, ensuring correct merging of values from different paths. This step processes all variable mentions in linear time relative to the program's size.[4] Overall, the algorithm achieves time complexity with efficient dominator computations and linear-time frontier and renaming phases, making it suitable for large-scale compilers even on unstructured code.[4]Optimizations and Variations

Pruned and Semi-Pruned SSA

Pruned static single-assignment (SSA) form refines the basic SSA representation by eliminating unnecessary φ-functions through the incorporation of live-variable analysis, ensuring that φ-functions are only placed where a variable is live upon entry to a convergence point. This approach, introduced in the seminal work on SSA construction, modifies the dominance frontier-based insertion algorithm: for each definition of a variable in a basic block , a φ-function for is inserted at nodes in the dominance frontier of only if is live on entry to those nodes, as determined by a prior backward data-flow analysis to compute liveness information. Such pruning recursively removes dead variables and their associated φ-functions, preventing the introduction of computations that have no impact on the program's observable behavior.[14] The construction of pruned SSA typically involves two phases aligned with liveness computation. First, a backward traversal of the control-flow graph marks live uses of variables starting from program exits and propagating backwards through definitions and uses, identifying variables that reach a use.[1] Then, during forward SSA renaming and φ-placement, unnecessary φ-functions are skipped, resulting in a sparser form without altering the semantic equivalence to the original program. This technique ensures that every φ-function has at least one transitive non-φ use, avoiding "dead" φ-functions that complicate analyses like constant propagation or dead code elimination.[14] Semi-pruned SSA offers a compromise between the full liveness analysis required for pruned SSA and the potentially excessive φ-functions in minimal SSA, by partially pruning based on local or block-boundary liveness without global computation. In this variant, before φ-insertion, variable names that are not live across basic block boundaries—such as those confined to a single block or dead after local uses—are eliminated, treating only "global" names (live into multiple blocks) as candidates for φ-functions.[2] The algorithm proceeds similarly to minimal SSA construction but skips φ-placement for locally dead variables, often via a simplified backward pass limited to intra-block or predecessor liveness checks, followed by forward elimination of redundant φ-operands where only one incoming value is live.[15] This keeps some potentially unnecessary φ-functions for variables that might be live in subsets of paths, prioritizing computational efficiency over maximal sparseness. Both pruned and semi-pruned SSA reduce the overall size of the intermediate representation by minimizing φ-functions, which in turn accelerates subsequent optimization passes and decreases memory usage during compilation.[2] Benchmarks on programs like those in SPEC CPU suites show that pruned SSA can eliminate up to 87% of superfluous φ-functions compared to minimal SSA, with an average reduction of about 70%, while semi-pruned variants achieve significant but lesser pruning at lower analysis cost.[16] These techniques improve compilation speed without requiring φ-placement at every dominance frontier.[2]Argument Passing Alternatives

Block arguments represent an alternative to traditional phi functions in static single-assignment (SSA) form by treating basic blocks as parameterized entities, similar to functions with input parameters. In this approach, values entering a basic block are explicitly passed as arguments from predecessor blocks via branch instructions, eliminating the need for special phi nodes at block entry points. This structural change maintains SSA's single-assignment property while making the intermediate representation (IR) more uniform, as all values—whether from computations or control-flow merges—are handled consistently. For instance, in systems like MLIR and Swift's SIL, a branch to a successor block includes explicit value bindings, such asbr ^successor(%value1, %value2), where %value1 and %value2 become the arguments of the successor block.[17][18]

The insertion of block arguments follows rules based on liveness analysis: arguments are added only for variables that are live-in to the block, meaning they are used before any redefinition within the block. This preserves SSA renaming, where each use refers to a unique definition from a specific predecessor path. Predecessors supply the appropriate SSA-renamed values during construction, ensuring that dominance relations guide the flow without requiring separate phi placement algorithms. In practice, this converts implicit control-flow edges in the control-flow graph (CFG) into explicit data dependencies, simplifying certain graph-based analyses but requiring explicit propagation of values along edges. For example, in a conditional branch, different values for the same logical variable are passed based on the path taken, mirroring phi semantics but embedded in the terminator instruction.[17][19]

This alternative simplifies optimizations and transformations by avoiding the special handling often needed for phi nodes, such as their non-atomic execution semantics or the challenges of unordered argument lists in blocks with many predecessors. It facilitates treating blocks as composable units, beneficial in modular IR designs like MLIR's dialect system or Swift SIL's high-level abstractions, and aligns well with graph-based compilers such as the Sea of Nodes approach in GraalVM, where data edges predominate over explicit CFGs. However, it increases explicitness in the IR, potentially complicating representations of unstructured control flow, such as exception handling, where values may be available only on specific edges without easy parameterization. Additionally, while pruning techniques can reduce unnecessary phis in traditional SSA, block arguments inherently avoid such redundant merges by design. Trade-offs include improved compile-time efficiency for analyses that iterate over uniform instructions but higher verbosity in IR size for programs with frequent merges.[17][18][20]

Precision and Sparseness Improvements

One key improvement in SSA precision involves conditional constant propagation, which leverages the structure of phi functions to identify and fold constants along specific control-flow paths. In SSA form, phi nodes merge values from predecessor blocks, allowing analyses to evaluate whether arguments to a phi are constant under certain conditions; if all relevant inputs to a phi resolve to the same constant value, that constant can be propagated forward, enabling folding of subsequent operations. This approach exploits the explicit def-use chains in SSA to perform path-sensitive constant propagation without requiring full path enumeration, improving the accuracy of optimizations like dead code elimination.[21] Sparse conditional constant propagation (SCCP) extends this by incorporating conditional values (e.g., top for unknown, bottom for overdefined, or specific constants) into the lattice used for data-flow analysis, thereby reducing the explosion of states in branch-heavy code. By propagating constants only along reachable paths—using two worklists to track SSA updates and control-flow reachability—SCCP marks unreachable branches as overdefined, allowing precise elimination of conditional code while maintaining SSA's single-assignment property. This sparsity arises from optimistic initialization and selective propagation, which avoids pessimistic approximations in loops and converges faster than traditional methods.[21] Post-2010 advancements in typed SSA have further enhanced precision for memory models by integrating type annotations directly into the SSA intermediate representation, as seen in formalizations of LLVM's IR. Typed SSA encodes memory operations (e.g., load/store) with type-safe pointers and aggregates, using a byte-oriented model to reason about alignment, padding, and aliasing without introducing undefined behaviors during transformations. This enables verified optimizations like memory-to-register promotion, where phi nodes for memory locations are minimized at domination frontiers. In loop-heavy code, such as those involving recursive data structures, this leads to sparser representations by eliminating redundant memory phis, improving analysis scalability. Recent work on handling aggregates in SSA avoids full scalar expansion by treating collections as first-class value types with dedicated operations, preserving logical structure in the IR. For instance, the MEMOIR framework represents sequential and associative data collections (e.g., arrays, maps) using SSA defs and uses for high-level operations like insert/remove, decoupling physical storage from logical access patterns. This maintains precision in element-level analyses—such as dead element elimination—while achieving sparseness through field elision and sparse data-flow, reducing memory usage by up to 20.8% and speeding up execution by 26.6% on benchmarks like SPECINT's mcf, particularly in loop-intensive sorting routines where phi proliferation is curtailed.[22]Deconstruction and Integration

Converting from SSA Form

Converting from static single-assignment (SSA) form back to traditional variable naming is a necessary step in compiler pipelines to prepare intermediate representations (IR) for code generation, as SSA's phi functions and subscripted variables are not directly executable on most hardware. This process, often called SSA deconstruction or un-SSA, primarily involves replacing phi functions with explicit copies while minimizing redundant assignments through optimization techniques. The goal is to preserve program semantics while reducing the number of introduced copies, which can impact code size and performance. Early approaches, such as those by Sreedhar et al., categorized deconstruction methods based on their use of interference analysis to insert copies selectively.[23] A key technique in SSA deconstruction is copy coalescing, which merges SSA variables that have a single static use—typically those connected via phi functions—into a single traditional variable, thereby eliminating unnecessary copy instructions. This is achieved by analyzing the live ranges of SSA variables and coalescing those without conflicts, often using graph-based methods to identify mergeable pairs. For instance, in a simple control-flow merge, a phi function likex_2 = phi(x_1, x_3) can be coalesced to reuse the name x if x_1 and x_3 do not interfere. Modern implementations prioritize aggressive coalescing before full deconstruction to focus on phi-related variables, reducing copies by up to 90% compared to naive methods.[23][24][25]

Interference analysis plays a central role in this process, modeling conflicts between SSA variables to determine which copies can be safely eliminated or coalesced. Variables are said to interfere if their live ranges overlap and they hold different values, as defined in SSA's value-numbering properties. This analysis constructs an interference graph where nodes represent SSA variables (or congruence classes of equivalent values), and edges indicate non-coalescable pairs based on liveness and value differences. Graph coloring on this structure assigns colors (names) to variables, enabling reuse and resolving phi-induced copies; unlike full register allocation, this focuses on name reuse rather than hardware constraints. Linear-time algorithms exploit SSA's dominance structure to build and color the graph efficiently, avoiding quadratic complexity.[24][23][26]

The standard algorithm for SSA deconstruction proceeds in structured steps to ensure correctness and efficiency:

- Compute liveness information: Determine live-in and live-out sets for each basic block using SSA-specific data-flow analysis, which identifies variables that must retain distinct names across merges. This step leverages fast liveness checks tailored to SSA, such as those using pruned SSA properties, to avoid inserting redundant copies.[23][25]

- Build the interference graph: Connect SSA variables (or phi operands) that interfere based on live-range overlaps and value equivalence, often grouping non-interfering phi arguments into live ranges via union-find structures. This graph captures dependencies from phi functions, enabling selective copy insertion only where necessary.[24][23]

- Perform register allocation or renaming: Color the interference graph to assign traditional names, coalescing non-adjacent nodes to merge variables. Remaining phi functions are translated to parallel copies in predecessor blocks, which are then sequentialized (e.g., via dependence graphs to break cycles) before final code emission. This step integrates with broader register allocation if performed post-optimization.[26][24][25]

if (cond) {

x_1 = a;

} else {

x_2 = b;

}

x_3 = phi(x_1, x_2); // Merge point

use(x_3);

if (cond) {

x_1 = a;

} else {

x_2 = b;

}

x_3 = phi(x_1, x_2); // Merge point

use(x_3);

x_1 and x_2 non-interfering at the phi, allowing coalescing to:

if (cond) {

x = a;

} else {

x = b; // Coalesced from x_2

}

use(x);

if (cond) {

x = a;

} else {

x = b; // Coalesced from x_2

}

use(x);

x_1 live across the else branch), a copy like x = x_2; is inserted in the else predecessor.[24][23]