Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zhao (state)

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Zhao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Zhao" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赵 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

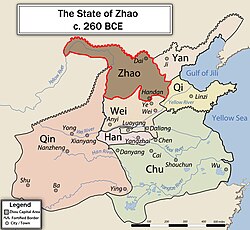

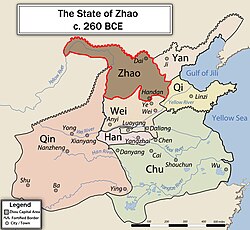

Zhao (traditional Chinese: 趙; simplified Chinese: 赵) was one of the seven major states during the Warring States period of ancient China. It emerged from the tripartite division of Jin, along with Han and Wei, in the 5th century BC. Zhao gained considerable strength from the military reforms initiated during the reign of King Wuling, but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Qin at the Battle of Changping. Its territory included areas in the modern provinces of Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Shanxi and Shaanxi. It bordered the states of Qin, Wei, and Yan, as well as various nomadic peoples including the Hu and Xiongnu. Its capital was Handan, in modern Hebei province.

Zhao was home to the administrative philosopher Shen Dao, Confucian Xun Kuang, and Gongsun Long, who is affiliated to the school of names.[1]

Origins and ascendancy

[edit]The Zhao clan within Jin had been accumulating power for centuries, including annexing the Baidi state of Dai in the mid-5th century BC.

At the end of the Spring and Autumn period, Jin was divided between three powerful ministers, one of whom was Zhao Xiangzi, patriarch of the Zhao family. In 403 BC, the Zhou king formally recognised the existence of the Zhao state along with two other states, Han and Wei. Some historians, beginning with Sima Guang, take this recognition to mark the beginning of the Warring States period.

At the beginning of the Warring States period, Zhao was one of the weaker states. Despite its extensive territory, its northern border was frequently harassed by the Eastern Hu, Forest Hu, Loufan, Xiongnu, and other northern nomadic peoples. Zhao lacked the military might of Wei or the wealth of Qi, and became a pawn in the struggle between them. This struggle came to a head in 354 BC when Wei invaded Zhao, forcing Zhao to seek help from Qi. The resulting Battle of Guiling was a major victory for Qi, reducing the threat to Zhao's southern border.

Zhao remained relatively weak until the military reforms of King Wuling of Zhao (325–299 BC). Zhao soldiers were ordered to dress like their Hu neighbours and to replace war chariots with cavalry archers (胡服骑射; 胡服騎射; húfúqíshè). This reform proved to be a brilliant and pragmatic strategy. With the advanced technology of the Chinese states and tactics of the steppe nomads, Zhao's cavalry became a powerful force. As a result, the newly empowered Zhao were more evenly matched with their greatest threat, Qi.

Zhao demonstrated its increased military prowess by conquering the state of Zhongshan in 295 BC after a protracted war and annexing territory from the neighbouring states of Wei, Yan, and Qin. During this time, Zhao cavalry also occasionally intruded into Qi during latter campaigns against Chu.

Several brilliant military commanders of the period served Zhao contemporaneously, including Lian Po, Zhao She, and Li Mu. Lian Po was instrumental in defending Zhao against Qin. Zhao She was most active in the east, leading the invasion of Yan. Li Mu defended Zhao against the Xiongnu in the Zhao–Xiongnu War and later against Qin.

Fall of Zhao

[edit]By the end of the Warring States period, Zhao was the only state strong enough to oppose the mighty Qin. An alliance with Wei against Qin began in 287 BC, but ended in defeat at Huayang in 273 BC. The struggle then culminated in the bloodiest battle of the entire period, the Battle of Changping in 260 BC. Zhao's forces were utterly defeated by Qin. Although the forces of Wei and Chu saved Handan from a subsequent siege by the victorious Qin, Zhao would never recover from the enormous loss of troops in the battle.

In 229 BC, invasions led by the Qin general Wang Jian were resisted by Li Mu and his subordinate officer Sima Shang (司馬尚) until 228 BC. Li Mu was one of the finest generals of the Warring States period, and although he was unable to defeat Wang Jian (also one of the best generals of the period), Wang Jian was unable to make any headway. The invasion ended in a stalemate. The Qin emperor, Qin Shihuang, realised that he needed to get rid of Li Mu in order to conquer Zhao, and tried to sow discord among the Zhao leadership. The Zhao king Youmiao fell for the plot: on the false advice of disloyal court officials and Qin infiltrators, he ordered Li Mu's execution and relieved Sima Shang of his duties. Li Mu's replacement, Zhao Cong, was promptly defeated by Wang Jian. Qin captured King Youmiao and defeated Zhao in 228 BC. Prince Jia, half-brother of King Qian, was proclaimed King Jia at Dai and led the last Zhao forces against the Qin. This regime lasted until 222 BC, when the Qin army captured him and defeated his forces at Dai.

A rebel named Wu Chen, following the example of Chen Sheng and Wu Guang in Chu, proclaimed himself King of Zhao. Wu was later killed by his subordinate Li Liang (李良), Zhang Er (張耳) and Chen Yu (陳餘), former officials of Zhao, created the Zhao royal Zhao Xie (趙歇) as King of Zhao. In 206 BC, the rebel lord Xiang Yu of Chu defeated the Qin dynasty and made himself and seventeen other lords kings, appointing Zhao Xie the king of Dai. Chen Yu helped Zhao Xie reclaim the land of Zhao from Zhang Er, so Zhao Xie created Chen Yu as Prince of Dai. In 205 BC, Chen Yu's subordinate in Dai, Xia Yue (夏說), was defeated by Liu Bang's generals Han Xin and Zhang Er. Chen Yu was defeated by Han Xin in 204 BC, and later Zhao Xie was killed by Han forces. Liu Bang gave the state of Zhao to Zhang Er.

In 154 BC, an unrelated Zhao, led by Prince of Zhao Liu Sui (劉遂), participated in the unsuccessful Rebellion of the Seven States (Chinese: 七國之亂) against the newly installed sixth emperor of the Han dynasty.

Culture and society

[edit]

Before Qin Shi Huang unified China in 221 BC, each region had its own customs and culture, although elite culture was identical throughout. In the Yu Gong (Tribute of Yu) chapter of the Book of Documents – probably written in the 4th century BC – China is described as divided into nine regions, each with its own distinctive peoples and products. The central theme of this section is that these nine regions are unified into one state through the travels of the eponymous sage, Yu the Great, and the sending of each region's unique goods to the capital as tribute. Other texts also discussed these regional differences in culture and physical environment.[2]

One such text was Wuzi (The Book of Master Wu), a military treatise of the Warring States, written in response to a request from Marquis Wu of Wei for advice on how to deal with the other states. Wu Qi, to whom work is attributed, explained that the government and nature of the people are linked to the physical environment and territory in which they live.[2]

Of Zhao, he said:

The two states of Han and Zhao train their troops rigorously but have difficulty in applying their skills to the battlefield.

— Wuzi, Master Wu

Han and Zhao are states of the Central Plain. Theirs are a gentle people, weary from war and experienced in arms, but have little regard for their generals. The soldiers' salaries are meager and their officers have no strong commitment to their countries. Although their troops are experienced, they cannot be expected to fight to the death. To defeat them, we must concentrate large numbers of troops in our attacks to present them with certain peril. When they counterattack, we must be prepared to defend our positions vigorously and make them pay dearly. When they retreat, we must pursue and give them no rest. This will grind them down.

— Wuzi, Master Wu

List of Zhao rulers

[edit]Before the partition of Jin

[edit]- Chengzi of Zhao

- Xuanzi of Zhao

- Zhuangzi of Zhao

- Wenzi of Zhao

- Jingzi of Zhao (趙景子)

- Jianzi of Zhao (趙簡子)

- Xiangzi of Zhao (趙襄子)

- Huanzi of Zhao (趙桓子)

After the partition of Jin

[edit]- Marquess Xian (獻侯), personal name Huan (浣), ruled 424 BC–409 BC

- Marquess Lie (烈侯), personal name Ji (籍), son of previous, ruled 409 BC–387 BC, noted for several reforms

- Marquess Jing (敬侯), personal name Zhang (章), son of previous, ruled 387 BC–375 BC

- Marquess Cheng (成侯), personal name Zhong (種), son of previous, ruled 375 BC–350 BC

- Marquess Su (肅侯), personal name Yu (語), son of previous, ruled 350 BC–326 BC

- King Wuling (武靈王), personal name Yong (雍), son of previous, ruled 326 BC–Spring 299 BC

- King Huiwen (惠文王), personal name He (何), son of previous, ruled Spring 299 BC–266 BC

- King Xiaocheng (孝成王), personal name Dan (丹), son of previous, ruled 266 BC–245 BC

- King Daoxiang (悼襄王), personal name Yan (偃), son of previous, ruled 245 BC–236 BC

- King Youmiao (幽繆王), personal name Qian (遷), son of previous, ruled 236 BC–228 BC

- Jia, King of Zhao (代王), personal name Jia (嘉), half-brother of previous, ruled 228 BC–222 BC

- Xie, King of Zhao (趙王歇), ruled 209 BC–205 BC. Also known as Zhao Xie. A reinstalled king of Zhao by rioting peasants during the reign of Qin Er Shi. Defeated and killed by Liu Bang.

Zhao in astronomy

[edit]There are two opinions about the representing star of Zhao in Chinese astronomy. The opinions are :

- Zhao is represented with the star Lambda Herculis in asterism Left Wall, Heavenly Market enclosure,[3] and also represented with two stars 26 Capricorni (趙一 Zhao yī, English: the First Star of Zhao) and 27 Capricorni (趙二 Zhao èr, English: the Second Star of Zhao) in asterism Twelve States, Girl mansion.[4] (see Chinese constellation).

- Zhao is represented with the star Lambda Herculis,[5] and also represented with star "m Capricorni".[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Huang Kejian (2016) [2010]. From Destiny to Dao: A Survey of Pre-Qin Philosophy in China. Silkroad Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-62320-070-1.

- ^ a b Lewis, Mark Edward (2009). The Early Chinese Empires : Qin and Han. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 11 - 16. ISBN 9780674024779.

- ^ Chen Huihua (陳輝樺), ed. (23 June 2006). "中國古代的星象系統 (54): 天市左垣、市樓". Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy 天文教育資訊網 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ zh:北方中西星名對照表

- ^ Richard Hinckley Allen (2021) [1963]. "Hercules". Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning.

- ^ Richard Hinckley Allen (2021) [1963]. "Capricornus". Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning.

Zhao (state)

View on GrokipediaGeography and territory

Location and borders

The state of Zhao occupied northern China, centered on the Taihang Mountains that demarcated its western boundary and provided a defensive barrier against incursions from Qin. Its core territory lay east of these mountains in the fertile alluvial plains drained by the Yellow River, supporting agriculture, while extending northward into transitional zones blending highlands with the expansive steppes conducive to pastoralism and cavalry development. This geographical positioning, spanning modern Hebei, Shanxi, and portions of Inner Mongolia, enabled Zhao to leverage diverse terrains for both sedentary farming in the south and adaptation to nomadic warfare tactics in the north.[6] Upon formal recognition following the partition of Jin in 403 BC, Zhao's initial borders encompassed the northern sectors of the former Jin domain, adjoining the newly established states of Wei and Han to the south, Yan to the east across the Zhang River valley, and nomadic groups like the Hu to the north. The southern frontier aligned roughly with the Yellow River, while the western edge hugged the Taihang range, limiting direct access to the Wei River valley held by Qin. These confines positioned Zhao as a buffer state, with the rugged Taihang passes serving as chokepoints that influenced defensive strategies amid interstate rivalries.[6] During the reign of King Wuling (325–299 BC), Zhao aggressively expanded its frontiers, incorporating the Dai region in the far north near the Yanmen Pass and subjugating intermediary polities such as Zhongshan, thereby extending borders to abut the upper Yellow River courses and deeper into steppe territories dominated by tribes like the Lin Hu and Lou Fan. Western advances under these campaigns brought Zhao into proximate rivalry with Qin, probing beyond the Taihang into Shanxi's loess plateaus. The resultant elongated north-south configuration, stretching over 800 kilometers, heightened exposure to flanking threats, as Qin's forces exploited mountain defiles to sever northern supply lines from southern agricultural bases, underscoring how terrain shaped Zhao's military imperatives.[3]Capitals and administrative centers

Handan served as the primary capital of the Zhao state following its relocation there around 386 BC, functioning as the central hub for governance and military command during the Warring States period.[6] The city's strategic location in the Hebei plain facilitated administration over core territories and supported a dense population through extensive urban infrastructure, including defensive walls enclosing an area of approximately 31 square kilometers.[2] Archaeological excavations at Handan reveal remnants of massive rammed-earth walls, palace foundations, and water management systems indicative of its capacity to sustain large-scale administrative operations and house elite bureaucrats alongside military garrisons.[7] These features underscore Handan's role in coordinating state policies and defending against southern rivals like Wei and Qin. In the north, Dai commandery emerged as a key administrative center around 300 BC, overseeing frontier defenses against nomadic incursions from the Hu peoples and steppe regions. Sites such as Dai Wang City exhibit preserved wall remnants, highlighting its function in maintaining garrisons and logistical support for Zhao's expansive northern territories without serving as a full secondary capital.[6] This decentralized structure allowed Zhao to balance central authority in Handan with regional control in peripheral areas vital for territorial integrity.Origins and establishment

Roots in the Jin state

The Zhao clan traced its origins to the fief of Zhao (near modern Hongdong, Shanxi), granted in the 10th century BCE to Zaofu, a charioteer who served King Mu of Zhou (r. circa 956–918 BCE) and was rewarded for his loyalty and skill in racing steeds.[6] This early establishment positioned the clan as vassals within the Zhou feudal system, with descent claimed from Ji Sheng, a collateral relative of the Qin lineage, integrating them into the broader aristocratic networks of the era.[6] As Jin expanded under its rulers during the Spring and Autumn period, the Zhao family aligned closely with the Jin ducal house, leveraging kinship ties and regional proximity to secure initial holdings. Prominence grew through consistent military and advisory service to Jin dukes, exemplified by Zhao Su (active 677–651 BCE), who received the Geng fief (near Hejin, Shanxi) under Duke Xian of Jin (r. 676–651 BCE) for contributions to state stability.[6] Subsequent figures like Zhao Shuai (Viscount Cheng, fl. 7th century BCE) advised Duke Wen of Jin (r. 637–628 BCE) during his campaigns for hegemony, earning the Yuan fief (near Jiyuan, Henan) and solidifying the clan's role in Jin's chariot-based warfare traditions.[8] Zhao Dun (Viscount Xuan, fl. late 7th century BCE) navigated succession crises under Duke Ling (r. 621–607 BCE), while Zhao Wu (Viscount Wen, fl. 6th century BCE) was appointed minister-commander under Duke Ping (r. 558–532 BCE) after surviving a near-extermination of the clan, reflecting their reliance on aristocratic patronage and infantry-supporting tactics inherited from Jin's multi-clan military structure.[6] By the 6th century BCE, these efforts accumulated fiefs in northern Jin territories, including expansions under Zhao Yang (Viscount Jian, r. 517–458 BCE), who occupied the Dai region (northern Shanxi), enhancing control over frontier areas vulnerable to non-Zhou polities.[6] Internal dynamics within Jin intensified rivalries among the great families, with the Zhao clan aligning strategically against dominant houses like Zhi. In 498 BCE, amid the Fan-Zhonghang rebellion, Zhao's ambiguous stance preserved its position amid shifting alliances.[6] A pivotal consolidation occurred in 454 BCE, when Zhao, alongside Han and Wei, partitioned the lands of Fan and Zhonghang clans, redistributing territories to bolster their collective dominance.[8] This tripartite cooperation peaked in 453 BCE, as Zhao Xiangzi, Han Kangzi, and Wei Huanzi orchestrated the assassination of Zhi Bo after his aggressive campaigns, flooding his stronghold and extinguishing the Zhi line, thereby eliminating the primary rival and establishing the three families' hegemony over Jin's administration and armies by the mid-5th century BCE.[8] These struggles underscored the Zhao clan's dependence on inter-clan pacts and Jin's decentralized command system, where control of regional forces and fiefs translated into de facto autonomy in northern domains.[6]Partition of Jin and independence (403 BC)

In 453 BC, the families of Han, Zhao, and Wei allied to defeat the dominant Zhi clan of Jin at the Battle of Jinyang, where they assassinated Zhi Bo and partitioned the Zhi territories among themselves, thereby establishing de facto control over Jin's military and administrative apparatus.[8] This victory marginalized the Jin ducal house, reducing it to a puppet authority unable to enforce central rule amid the families' entrenched regional power bases and private armies. The alliance's overwhelming dominance stemmed from their coordinated military strategy—flooding the Zhi besiegers—and subsequent absorption of Zhi resources, which precluded any effective Jin counteroffensive. Seeking dynastic legitimacy, the three families petitioned the Zhou court, and in 403 BC, King Weilie formally enfeoffed Han Kangzi, Zhao Xiangzi, and Wei Huanzi as marquesses, recognizing Han, Zhao, and Wei as independent states and extinguishing Jin's nominal sovereignty.[8] This diplomatic sanction by the weakening Zhou authority ratified the partition without direct military confrontation in that year, reflecting the court's pragmatic deference to entrenched regional powers rather than feudal hierarchy. Post-recognition challenges included finalizing the division of Jin's remaining assets, culminating in 376 BC when the three marquesses extinguished the Jin ruling line to eliminate lingering claims and resolve overlapping administrative claims.[8] Zhao's allotted territories emphasized northern expanses in modern Shanxi, featuring defensible mountains and access to steppe-adjacent lands that bordered non-Zhou tribes, conferring inherent positional advantages for mobility-oriented defenses.[6] Border delineations among the trio involved negotiations over inherited fiefs, averting immediate war but sowing seeds for later interstate frictions.Rise and military ascendancy

Reforms under King Wuling (325–299 BC)

King Wuling of Zhao, reigning from 325 to 299 BC, initiated military reforms driven by the need to counter frequent raids by northern Hu nomads, whose cavalry tactics exploited the limitations of Zhao's traditional chariot-based forces. These reforms prioritized adaptability to terrain and enemy mobility over adherence to Zhou ritual norms, enabling Zhao's army to match the speed and archery prowess of steppe warriors.[3][9] In 307 BC, King Wuling decreed the adoption of Hu fu (胡服), nomadic-style attire consisting of trousers, short jackets, and boots, which replaced the loose robes of Zhou elites that impeded mounted movement. This change facilitated effective horseback riding and archery, allowing soldiers to shoot accurately while galloping, thereby extending operational range and responsiveness against hit-and-run nomad incursions.[3] Concurrently, he abolished reliance on cumbersome war chariots—previously the core of Zhou infantry support—and established training regimens for mounted archers (qi she, 骑射), drawing techniques from Hu practices observed during diplomatic missions. These shifts causally enhanced army velocity, as chariots were terrain-limited and slow to maneuver compared to cavalry units capable of rapid deployment over vast northern steppes.[9][10] The reforms encountered staunch opposition from conservative ministers, who contended that Hu fu violated ancestral rites and risked derision from other states, potentially undermining Zhao's legitimacy. King Wuling overcame this resistance through resolute leadership, publicly donning the attire himself, conducting demonstrations of its practical superiority in drills, and engaging in debates to affirm that military efficacy trumped ceremonial tradition amid existential threats. This internal resolution underscored the reforms' foundation in empirical necessity rather than ideological fancy, as Zhao's prior defeats against Hu cavalry validated the tactical imperatives.[3]Expansion and key campaigns

Following the military reforms instituted by King Wuling, Zhao leveraged its newly developed cavalry capabilities to pursue territorial expansion, particularly against northern adversaries and rival states. In 295 BC, Zhao completed the conquest of the neighboring state of Zhongshan after a prolonged conflict spanning over two decades, utilizing mounted archers and infantry to overcome Zhongshan's defenses and secure fertile lands in central Hebei.[11] This victory, achieved through superior mobility that outflanked Zhongshan's static forces, eliminated a persistent threat to Zhao's northeastern borders and provided strategic depth against nomadic incursions.[9] Zhao's campaigns extended northward against semi-nomadic tribes such as the Linhu and Loufan, whom King Wuling subdued around 300 BC, incorporating territories in the Ordos region and establishing commanderies like Yunzhong to control the Yellow River's northern loop.[6] These operations demonstrated the practical application of "Hu attire" and cavalry tactics, enabling rapid strikes that disrupted tribal alliances and extended Zhao's influence into steppe-adjacent areas previously vulnerable to raids. In 284 BC, Zhao joined a coalition with Qin, Yan, Wei, and Han to invade Qi, sacking its capital Linzi and weakening Qi's dominance in the east, though Zhao gained limited direct territorial gains from the expedition.[12] To counter Qin's westward aggression, Zhao conducted incursions into Qin-held territories, notably defeating Qin armies at the Battle of Eyu in 270 BC under General Zhao She, who exploited terrain and feigned retreats to inflict heavy losses and reclaim borderlands.[12] Zhao frequently allied with eastern states like Qi and Wei in vertical coalitions aimed at halting Qin's expansion, as seen in diplomatic efforts around 318 BC and subsequent joint campaigns that temporarily checked Qin advances through coordinated offensives. These alliances reflected pragmatic power balancing, where Zhao traded military support for mutual defense against the increasingly dominant western state.[13]Government and administration

Political structure and bureaucracy

The political structure of Zhao centered on a hereditary monarchy, with the king holding supreme authority over political, military, and judicial decisions, advised by a council comprising the chancellor (xiang) responsible for civilian administration, fiscal policy, and legal oversight, alongside key generals who influenced strategic deliberations.[14] This hierarchy facilitated centralized decision-making, enabling rapid mobilization of resources for warfare, as the chancellor's role in coordinating edicts and appointments ensured alignment between court policies and frontier needs. Factional struggles, such as those arising from succession disputes where royal nominations of non-primary heirs provoked noble rebellions, periodically disrupted this council, underscoring tensions between royal prerogative and aristocratic interests that could delay military campaigns.[14] Provincial governance relied on commanderies (jun), each administered by a governor (junshou) appointed by the king, who enforced laws, collected taxes, and supervised corvée labor essential for infrastructure and army provisioning.[14] These governors operated semi-autonomously in border regions, reporting directly to the central court to maintain oversight, with local districts (xian) under magistrates handling day-to-day enforcement; this structure linked administrative efficiency to military efficacy by streamlining labor drafts for fortifications and troop levies, reducing delays in sustaining prolonged conflicts.[14] Reforms in the late 4th century BCE, building on earlier centralizing efforts, curtailed hereditary aristocratic privileges by diminishing noble land exemptions and favoring merit-based appointments of professional officials over clan-based nobility, as seen in the adoption of standardized legal codes like Zhao's Guolü that prioritized state revenue over feudal exemptions.[14] This shift enhanced bureaucratic competence, allowing the king to bypass entrenched factions for loyal administrators who optimized resource allocation, thereby bolstering military logistics and contributing to Zhao's ascendancy through more reliable command chains and reduced internal sabotage risks.[14]Legal and military organization

Zhao's legal framework drew on Legalist principles prevalent during the Warring States period, prioritizing strict codified laws, merit-based rewards, and harsh punishments to centralize authority and bolster military effectiveness. Rewards were granted for military accomplishments, such as 100 pieces of gold for capturing an enemy general, incentivizing valor and discipline while punishing desertion or cowardice severely to deter disloyalty.[9] This system, mirroring aspects of Shang Yang's reforms in Qin—where ranks and land were tied to battlefield merits—promoted state loyalty over kinship, fostering cohesion in a period of intense interstate rivalry.[15] Militarily, Zhao organized a professional standing army that could mobilize over 500,000 troops by the late fourth century BCE, comprising infantry phalanxes, residual chariot units, and specialized cavalry divisions adapted from northern nomadic practices. Cavalry forces, numbering in the tens of thousands, emphasized mobility and archery, marking an organizational shift from traditional Zhou-era reliance on chariots to versatile mounted units suited to Zhao's expansive northern frontiers.[16] Conscription was enforced on able-bodied adult males, integrated with land tenure under evolved well-field principles, requiring periodic training and service quotas proportional to holdings to sustain agricultural productivity alongside military readiness. This linkage ensured broad societal participation, with exemptions rare and tied to state needs, enabling rapid army expansion while maintaining internal discipline through Legalist oversight.[9]Economy and resources

Agriculture and trade

The economy of Zhao centered on agriculture adapted to its northern terrain, primarily involving the cultivation of drought-resistant millets such as foxtail and broomcorn varieties in the valleys of rivers like the Hutuo and Zhang. These crops formed the staple diet, with yields supported by inherited irrigation techniques from the Jin period, including rudimentary canals and wells to mitigate semi-arid conditions. Wheat cultivation emerged as a secondary crop during the mid-to-late Warring States era, contributing to a mixed millet-wheat system in the North China Plain, though overall agricultural output remained limited due to comparatively barren soils and lower fertility relative to southern states like Chu or Qi.[17][18] Trade networks were essential for supplementing domestic resources, particularly through border exchanges with northern nomadic groups such as the Hu and Loufan, where Zhao bartered surplus grain, iron implements, and metals for high-quality warhorses critical to its cavalry reforms under King Wuling around 307 BC. These caravan-based transactions, often involving direct steppe frontier routes rather than formalized long-distance paths, enabled the importation of animals suited for mounted warfare, compensating for local shortages of robust equine stock.[19][20] State intervention in markets prioritized military provisioning, with regulations ensuring grain and commodity flows to armies amid constant warfare; Zhao issued spade-shaped bronze currency circa 300–250 BC to facilitate standardized exchange and economic mobilization, reflecting broader Warring States trends toward monetization and centralized control over trade to sustain large-scale campaigns.[21]Mining, metallurgy, and military production

The state of Zhao developed substantial iron smelting capabilities during the Warring States period, enabling the production of durable weapons and armor that enhanced its military effectiveness. Archaeological investigations in the Handan region, the capital area of Zhao, have uncovered iron smelting sites such as that at Jingji Village in Wu'an County, dating to the Warring States era, where bloomery processes were employed to process local iron ores into workable metal for armaments.[22] These sites demonstrate advancements in furnace technology, including early blast furnace precursors, which allowed for higher yields of iron suitable for forging swords, spearheads, and lamellar armor superior in hardness and availability compared to bronze equivalents prevalent earlier in the Zhou dynasty.[23] State oversight extended to bronze and iron production, functioning as de facto monopolies to ensure standardized arsenals for Zhao's armies, a practice common among Warring States powers to maintain uniformity in weaponry amid constant warfare. Iron artifacts from Zhao tombs, including swords and tools analyzed metallurgically, reveal techniques like decarburization of cast iron into steel, yielding blades with improved edge retention by the mid-4th century BC.[24] This standardization facilitated mass production, as evidenced by the consistency in alloy compositions and forging marks on excavated pieces, prioritizing military output over civilian use. The scale of Zhao's metallurgical operations underpinned its adoption of large cavalry units under reforms like those of King Wuling (r. 325–299 BC), requiring vast quantities of iron for horse fittings, lances, and protective gear to equip thousands of mounted troops. Production capacities, inferred from slag volumes and furnace remnants near resource-rich northern territories, supported field armies exceeding 100,000, with iron's abundance reducing reliance on scarcer bronze and enabling sustained campaigns against nomadic threats and rival states.[25]Society and culture

Social hierarchy and daily life

The social hierarchy of Zhao mirrored the stratified structure prevalent across Warring States polities, featuring the king as sovereign, followed by hereditary nobles (gongqing) who held fiefs and advisory roles, and appointed officials (daifu) managing administration and military affairs. Lower strata included the shi class—retainers, scholars, and warriors—who gained status through service, with notable opportunities for advancement via military merit, as the state offered substantial rewards like 100 pieces of gold for capturing an enemy general. Commoners, comprising the vast majority, were divided into farmers (the economic foundation, obligated to corvée labor and taxation), artisans specializing in crafts such as bronze work, and merchants engaged in trade, though the latter ranked lowest due to Confucian-influenced disdain for profit-seeking. Slaves, often war captives or debtors, performed menial tasks at the hierarchy's base.[9][14] Family clans descended from Jin's partitioning nobles wielded enduring influence, controlling landholdings and intermarrying to preserve power, even amid centralizing reforms that curtailed feudal fragmentation; the ruling Zhao lineage itself exemplified this patrilineal dominance, with succession disputes underscoring clan dynamics.[6] Daily life for rural farmers centered on millet and wheat cultivation under state-assigned plots, punctuated by onerous corvée duties for infrastructure like walls and canals, alongside recurrent conscription that depleted labor and imposed survival hardships during campaigns. Urban dwellers in Handan, the capital, experienced denser commerce in markets trading grain, iron tools, and luxuries, alongside palace-centered entertainments and administrative routines, fostering a vibrant yet militarized atmosphere in a city noted for its developed culture and fortifications.[2]Adoption of northern nomadic influences

Under King Wuling of Zhao (r. 325–299 BC), the state implemented the hufuqishe policy in 307 BC, mandating the adoption of Hu-style clothing and mounted archery tactics from northern nomadic groups such as the Linhu and Loufan tribes.[26][27] This reform replaced traditional Chinese war chariots and heavy infantry formations with light cavalry units, enabling greater mobility on the open steppes where Zhao's northern borders faced frequent raids.[28] The Hu attire—consisting of trousers, tight-sleeved jackets, boots, and belts—facilitated horseback riding and archery, addressing the limitations of loose robes and chariot-based warfare that hindered pursuit and evasion against horse-mounted foes.[29] The shift emphasized pragmatic military utility, as Zhao's terrain and adversaries demanded rapid, flexible forces over ritualized infantry arrays; post-reform campaigns demonstrated this by swiftly annexing the Dai and Yunzhong regions, subduing nomadic tribes, and securing tribute in horses to bolster cavalry numbers.[26][20] Archery training integrated nomadic techniques, with Zhao soldiers practicing composite bows from horseback, which increased combat effectiveness in asymmetric warfare against faster steppe horsemen.[10] These borrowings were not wholesale cultural assimilation but targeted adaptations: Zhao retained core infantry and administrative structures while enhancing equine resources through conquest-driven tribute systems, yielding thousands of horses annually from allied or vassalized tribes.[16] Initial resistance arose from conservative elites who viewed Hu clothing as barbaric and unbefitting Zhou ritual norms, prompting debates that King Wuling overcame by enforcing the policy on his forces first, leading to gradual normalization as victories validated the changes.[19] By the late 4th century BC, these influences had causally entrenched in Zhao's military doctrine, enabling sustained expansion northward and deterring nomadic incursions, though they did not extend to broader societal adoption beyond the army.[30] This selective integration reflected environmental imperatives—steppe ecology favored mounted warfare—rather than ideological affinity, positioning Zhao as the first Warring States power to operationalize such tactics at scale.[31]Decline and fall

Major defeats, including Battle of Changping (260 BC)

In 273 BC, a joint force of Zhao and Wei states suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Huayang against Qin reinforcements aiding Han, resulting in the loss of approximately 150,000 troops from the allied armies and weakening Zhao's southern defenses.[12] This engagement, led by Qin's general Bai Qi, demonstrated Zhao's vulnerability in coalition warfare and contributed to the gradual erosion of its territorial buffers against Qin expansion.[32] The Battle of Changping in 260 BC marked the most catastrophic defeat for Zhao, decisively crippling its military power. Qin forces, under Bai Qi, invaded the Shangdang region seized from Zhao in 262 BC, prompting Zhao King Xiaocheng to mobilize around 450,000 troops under initial command of the experienced general Lian Po, who adopted a defensive strategy that stalemated Qin advances for three years.[33] Internal court pressures, including slanders against Lian Po's caution as cowardice and advocacy from figures close to the Zhao Kuo family, led to his replacement by Zhao Kuo, a theorist lacking practical command experience whose father had cautioned against his appointment.[32] Zhao Kuo's aggressive offensive shifted the dynamics, allowing Bai Qi to feign weakness, lure the Zhao army into overextended positions, and sever its supply lines through rapid maneuvers and entrenchments.[33] Encircling roughly 400,000 Zhao soldiers, Qin forces induced famine over 46 days, culminating in mass surrender; Bai Qi then ordered the execution of most captives—estimated at over 400,000—by burial alive, sparing only about 240 youths to spread tales of defeat, while Zhao Kuo was killed in the chaos.[32] Total Zhao casualties exceeded 450,000, representing a irrecoverable depletion of its manpower reserves and shattering its capacity to field large armies thereafter, as subsequent campaigns revealed diminished mobilization.[33] This outcome stemmed not merely from tactical encirclement but from Zhao's internal failures in leadership continuity and resistance to attrition warfare, contrasting Qin's disciplined reforms under Shang Yang.[9]Final conquest by Qin (228 BC)

In 228 BC, Qin general Wang Jian, exploiting the recent execution of Zhao's defensive commander Li Mu, launched a decisive campaign against the weakened state. Zhao's replacement general, Zhao Cong, suffered rapid defeats, allowing Qin forces to advance unhindered and besiege the capital Handan.[6][34] The siege, compounded by Zhao's exhaustion from prior protracted conflicts including massive casualties at Changping and subsequent border wars, strained the city's resources and morale, leading to its eventual capitulation after several months.[6] Handan fell to Wang Jian and allied general Xin Sheng, who captured King Youmiu (also known as King Qian).[6][34] The king surrendered and was exiled to the remote Fangling region in southern Qin territory, where he later died.[34] With the royal house subdued, Qin annexed core Zhao territories, reorganizing them into administrative commanderies such as Handan Commandery to integrate the region systematically into its bureaucracy and military structure.[6] Decades of unrelenting warfare had inflicted severe depopulation on Zhao, with estimates from historical annals indicating hundreds of thousands perished or displaced across campaigns, leaving the state demographically vulnerable to Qin's superior logistics and reinforcements.[6] A brief remnant resistance formed when Prince Jia, half-brother to the late King Xiaocheng, escaped to the northern Dai commandery, proclaiming himself king and rallying survivors; however, this holdout maintained only nominal independence until Qin's full subjugation in 222 BC.[6][34] The conquest effectively terminated Zhao's sovereignty, paving Qin's path to unify the Warring States.[6]Rulers of Zhao

Rulers before the partition of Jin

The Zhao clan originated as a subordinate lineage within the state of Jin during the Spring and Autumn period, with its leaders serving as ministers, advisors, and military commanders under Jin's dukes, gradually accumulating territory and influence through participation in expansionist campaigns.[6] These early rulers laid the groundwork for Zhao's later martial prowess by contributing to Jin's dominance over northern tribes and rival states, including conflicts against the Rong peoples, Zheng, and Chu, which honed cavalry tactics and territorial control in the Shanxi region.[6] The founder of the Zhao lineage, Zhao Su (also known as the Lord of Geng), participated in Duke Xian of Jin's (r. 677–651 BC) campaigns against the states of Huo, Wei, and Geng, earning territorial rewards that established the clan's initial base.[6] Succeeding him, Zhao Chengzi (Viscount Cheng, or Zhao Shuai) advised Duke Wen of Jin (r. 636–628 BC) in achieving hegemon status and served as grand master of the Yuan commandery, strengthening administrative roles.[6] Zhao Xuanzi (Viscount Xuan, or Zhao Dun), active under Duke Ling of Jin (r. 621–607 BC), acted as a key advisor amid succession intrigues and was implicated in the duke's assassination, highlighting the clan's entanglement in Jin's internal power struggles.[6] His successor, Zhao Zhuangzi (Viscount Zhuang, or Zhao Shuo), led military expeditions against Zheng and Chu but perished in a plot targeting the Zhao family, underscoring the precarious yet formative rivalries that tempered the clan's resilience.[6] Restoration followed under Zhao Wenzi (Viscount Wen, or Zhao Wu), who, after surviving a massacre of the Zhao lineage, was appointed minister-commander in 545 BC during Duke Ping of Jin's reign (r. 558–532 BC), aiding in the clan's revival and continued service in Jin's hegemonic efforts.[6] Zhao Jianzi (Viscount Jian, or Zhao Yang; r. ca. 517–458 BC) further consolidated power by supporting Zhou King Jing and through conquests that expanded Zhao holdings, while Zhao Xiangzi (Viscount Xiang, or Zhao Wuxu; r. ca. 458–425 BC) decisively conquered the state of Dai and allied with the Han and Wei clans to eliminate the rival Zhi clan, securing vast territories in preparation for Jin's fragmentation.[6] These actions, drawn from Jin annals and later compiled in Sima Qian's Shiji (chapter 43, "Zhao shijia"), demonstrate how the Zhao leaders' military engagements under Jin fostered a tradition of aggressive expansion and strategic alliances.[6]Rulers after the partition of Jin

The rulers of Zhao following the formal partition of Jin in 403 BCE, when the Zhou king recognized Zhao as a marquis alongside Han and Wei, transitioned from marquisal to kingly titles amid growing autonomy during the Warring States period.[6] Initial rulers focused on consolidating territory and relocating the capital, while later ones implemented military reforms and faced escalating conflicts with Qin.[6]| Title | Reign Years | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Marquis Lie (Liehou) | 409–400 BCE | Oversaw recognition as marquis in 403 BCE; relocated capital to Zhongmou for strategic defense.[6] |

| Marquis Wu (Wuhou) | 400–387 BCE | Brief reign marked by administrative stability but no major recorded expansions or reforms.[6] |

| Marquis Jing (Jinghou) | 387–375 BCE | Shifted capital to Handan, enhancing economic and military positioning; engaged in conflicts with Wei and Qi.[6] |

| Marquis Cheng (Chenghou) | 375–350 BCE | Navigated succession disputes; allied with Qi, benefiting from their victory at the Battle of Guiling against Wei in 354 BCE.[6] |

| Marquis Su (Suhou) | 350–326 BCE | Constructed fortifications along the northern border to counter incursions by nomadic tribes.[6] |

| King Wuling | 326–299 BCE | Proclaimed kingship, symbolizing independence; enacted hu-fu (nomad-style) reforms promoting cavalry and mounted archery, enabling conquests of Zhongshan state (305, 303, 300 BCE).[6] |

| King Huiwen | 299–266 BCE | Repelled Qin forces at the Battle of Eyu (280 BCE); contended with internal rebellions and power struggles.[6] |

| King Xiaocheng (Filial Cheng) | 266–245 BCE | Suffered catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Changping (260 BCE), losing approximately 400,000 troops to Qin; endured prolonged siege of Handan.[6] |

| King Daoxiang | 245–236 BCE | Achieved victory over Yan; formed alliances against Qin, including in 241 BCE, amid ongoing territorial pressures.[6] |

| King Youmiu | 236–228 BCE | Oversaw final phase of decline; Handan fell to Qin conquest in 228 BCE, ending Zhao's independence.[6] |