Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Temporal fenestra

View on Wikipedia

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the temporal region of the skull of some amniotes, behind the orbit (eye socket). These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of reptiles. Temporal fenestrae are commonly (although not universally) seen in the fossilized skulls of dinosaurs and other sauropsids (the total group of reptiles, including birds).[1] The major reptile group Diapsida, for example, is defined by the presence of two temporal fenestrae on each side of the skull. The infratemporal fenestra, also called the lateral temporal fenestra or lower temporal fenestra, is the lower of the two and is exposed primarily in lateral (side) view.

The supratemporal fenestra, also called the upper temporal fenestra, is positioned above the other fenestra and is exposed primarily in dorsal (top) view. In some reptiles, particularly dinosaurs, the parts of the skull roof lying between the supratemporal fenestrae are thinned out by excavations from the adjacent fenestrae. These extended margins of thinned bone are called supratemporal fossae.

Synapsids, including mammals, have one temporal fenestra, which is ventrally bordered by a zygomatic arch composed of the jugal and squamosal bones. This single temporal fenestra is homologous to the infratemporal fenestra, as displayed most clearly by early synapsids.[2] In later synapsids, the cynodonts, the orbit fused with the fenestral opening after the latter had started expanding within the therapsids. Most mammals have this merged configuration. Later, primates re-evolved an orbit separated from the temporal fossa. This separation was achieved by the evolution of a postorbital bar, with haplorhines (dry-nosed primates) later evolving a postorbital septum.[3]

Physiological speculation associates temporal fenestrae with a rise in metabolic rates and an increase in jaw musculature. The earlier amniotes of the Carboniferous did not have temporal fenestrae, but two more advanced lines did: the synapsids (stem-mammals and mammals) and the diapsids (most reptiles and later birds).

Fenestration types

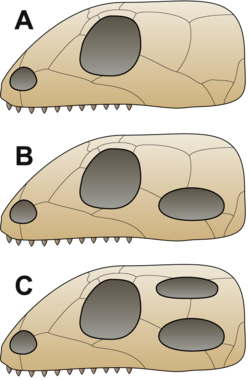

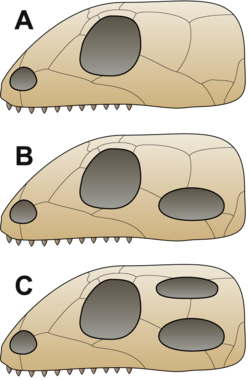

[edit]There are four types of amniote skull, classified by the number and location of their temporal fenestrae. Though historically important for understanding amniote evolution, some of these configurations have little relevance to modern phylogenetic taxonomy. The four types are:

- Anapsida – No openings. The plesiomorphic ("primitive") condition exemplified by amphibians as well as some early reptiles like captorhinids and parareptiles. Turtles have an anapsid skull, but this was likely acquired secondarily from a diapsid ancestor.

- Synapsida – One low opening (beneath the postorbital and squamosal bones). A monophyletic group including mammals and their ancestors.

- Euryapsida – One high opening (above the postorbital and squamosal bones). Euryapsids are a polyphyletic group, as reptiles with euryapsid skulls lack a shared common ancestor. Euryapsids evolved from a diapsid configuration, losing their lower temporal fenestra. Examples of euryapsid reptiles include ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, placodonts, and Trilophosaurus.

- Diapsida – Two openings. A monophyletic group including all modern reptiles and birds. Turtles, though not diapsids in a purely anatomical sense, qualify as members of the clade Diapsida due to their likely diapsid ancestry. Some diapsids, particularly modern lizards, have an infratemporal fenestra which is open from below due to a lack of contact between the jugal and quadratojugal bones.

Notes

[edit]- ^ These are idealized skulls

References

[edit]- ^ Werneburg, Ingmar (2019). "Morphofunctional Categories and Ontogenetic Origin of Temporal Skull Openings in Amniotes". Frontiers in Earth Science. 7. doi:10.3389/feart.2019.00013. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ Abel, Pascal; Werneburg, Ingmar (October 2021). "Morphology of the temporal skull region in tetrapods: research history, functional explanations, and a new comprehensive classification scheme". Biological Reviews. 96 (5): 2229–2257. doi:10.1111/brv.12751. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 34056833. S2CID 235256536. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Campbell, B. G. & Loy, J. D. (2000). Humankind Emerging (8th ed.). Allyn & Bacon. p. 85. ISBN 0-673-52364-0.