Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cartilage

View on Wikipedia| Cartilage | |

|---|---|

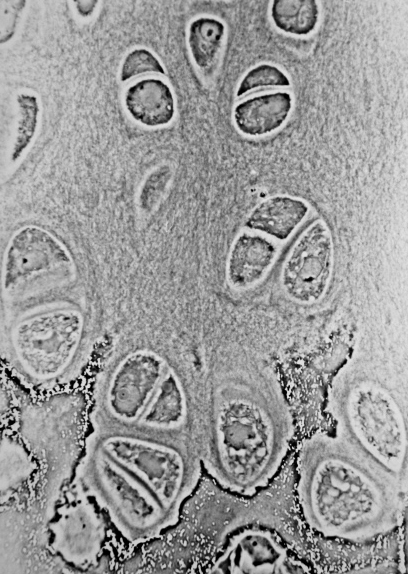

Light micrograph of undecalcified hyaline cartilage showing chondrocytes and organelles, lacunae and matrix. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D002356 |

| TA98 | A02.0.00.005 |

| TA2 | 381 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. Semi-transparent and non-porous, it is usually covered by a tough and fibrous membrane called perichondrium. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage,[1] and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck and the bronchial tubes, and the intervertebral discs. In other taxa, such as chondrichthyans and cyclostomes, it constitutes a much greater proportion of the skeleton.[2] It is not as hard and rigid as bone, but it is much stiffer and much less flexible than muscle or tendon. The matrix of cartilage is made up of glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, collagen fibers and, sometimes, elastin. It usually grows quicker than bone.

Because of its rigidity, cartilage often serves the purpose of holding tubes open in the body. Examples include the rings of the trachea, such as the cricoid cartilage and carina.

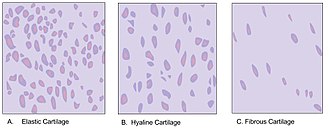

Cartilage is composed of specialized cells called chondrocytes that produce a large amount of collagenous extracellular matrix, abundant ground substance that is rich in proteoglycan and elastin fibers. Cartilage is classified into three types — elastic cartilage, hyaline cartilage, and fibrocartilage — which differ in their relative amounts of collagen and proteoglycan.

As cartilage does not contain blood vessels or nerves, it is insensitive. However, some fibrocartilage such as the meniscus of the knee has partial blood supply. Nutrition is supplied to the chondrocytes by diffusion. The compression of the articular cartilage or flexion of the elastic cartilage generates fluid flow, which assists the diffusion of nutrients to the chondrocytes. Compared to other connective tissues, cartilage has a very slow turnover of its extracellular matrix and is documented to repair at only a very slow rate relative to other tissues.

Structure

[edit]Development

[edit]In embryogenesis, the skeletal system is derived from the mesoderm germ layer. Chondrification (also known as chondrogenesis) is the process by which cartilage is formed from condensed mesenchyme tissue, which differentiates into chondroblasts and begins secreting the molecules (aggrecan and collagen type II) that form the extracellular matrix. In all vertebrates, cartilage is the main skeletal tissue in early ontogenetic stages;[3][4] in osteichthyans, many cartilaginous elements subsequently ossify through endochondral and perichondral ossification.[5]

Following the initial chondrification that occurs during embryogenesis, cartilage growth consists mostly of the maturing of immature cartilage to a more mature state. The division of cells within cartilage occurs very slowly, and thus growth in cartilage is usually not based on an increase in size or mass of the cartilage itself.[6] It has been identified that non-coding RNAs (e.g. miRNAs and long non-coding RNAs) as the most important epigenetic modulators can affect the chondrogenesis. This also justifies the non-coding RNAs' contribution in various cartilage-dependent pathological conditions such as arthritis, and so on.[7]

Articular cartilage

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (April 2025) |

The articular cartilage function is dependent on the molecular composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM consists mainly of proteoglycan and collagens. The main proteoglycan in cartilage is aggrecan, which, as its name suggests, forms large aggregates with hyaluronan and with itself.[8] These aggregates are negatively charged and hold water in the tissue. The collagen, mostly collagen type II, constrains the proteoglycans. The ECM responds to tensile and compressive forces that are experienced by the cartilage.[9] Cartilage growth thus refers to the matrix deposition, but can also refer to both the growth and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Due to the great stress on the patellofemoral joint during resisted knee extension, the articular cartilage of the patella is among the thickest in the human body. The ECM of articular cartilage is classified into three regions: the pericellular matrix, the territorial matrix, and the interterritorial matrix.

Function

[edit]Mechanical properties

[edit]The mechanical properties of articular cartilage in load-bearing joints such as the knee and hip have been studied extensively at macro, micro, and nano-scales. These mechanical properties include the response of cartilage in frictional, compressive, shear and tensile loading. Cartilage is resilient and displays viscoelastic properties.[10]

Since cartilage has interstitial fluid that is free-moving, it makes the material difficult to test. One of the tests commonly used to overcome this obstacle is a confined compression test, which can be used in either a 'creep' or 'relaxation' mode.[11][12] In creep mode, the tissue displacement is measured as a function of time under a constant load, and in relaxation mode, the force is measured as a function of time under constant displacement. During this mode, the deformation of the tissue has two main regions. In the first region, the displacement is rapid due to the initial flow of fluid out of the cartilage, and in the second region, the displacement slows down to an eventual constant equilibrium value. Under the commonly used loading conditions, the equilibrium displacement can take hours to reach.

In both the creep mode and the relaxation mode of a confined compression test, a disc of cartilage is placed in an impervious, fluid-filled container and covered with a porous plate that restricts the flow of interstitial fluid to the vertical direction. This test can be used to measure the aggregate modulus of cartilage, which is typically in the range of 0.5 to 0.9 MPa for articular cartilage,[11][12][13] and the Young's Modulus, which is typically 0.45 to 0.80 MPa.[11][13] The aggregate modulus is "a measure of the stiffness of the tissue at equilibrium when all fluid flow has ceased",[11] and Young's modulus is a measure of how much a material strains (changes length) under a given stress.

The confined compression test can also be used to measure permeability, which is defined as the resistance to fluid flow through a material. Higher permeability allows for fluid to flow out of a material's matrix more rapidly, while lower permeability leads to an initial rapid fluid flow and a slow decrease to equilibrium. Typically, the permeability of articular cartilage is in the range of 10^-15 to 10^-16 m^4/Ns.[11][12] However, permeability is sensitive to loading conditions and testing location. For example, permeability varies throughout articular cartilage and tends to be highest near the joint surface and lowest near the bone (or "deep zone"). Permeability also decreases under increased loading of the tissue.

Indentation testing is an additional type of test commonly used to characterize cartilage.[11][14] Indentation testing involves using an indentor (usually <0.8 mm) to measure the displacement of the tissue under constant load. Similar to confined compression testing, it may take hours to reach equilibrium displacement. This method of testing can be used to measure the aggregate modulus, Poisson's ratio, and permeability of the tissue. Initially, there was a misconception that due to its predominantly water-based composition, cartilage had a Poisson's ratio of 0.5 and should be modeled as an incompressible material.[11] However, subsequent research has disproven this belief. The Poisson's ratio of articular cartilage has been measured to be around 0.4 or lower in humans [11][14] and ranges from 0.46–0.5 in bovine subjects.[15]

The mechanical properties of articular cartilage are largely anisotropic, test-dependent, and can be age-dependent.[11] These properties also depend on collagen-proteoglycan interactions and therefore can increase/decrease depending on the total content of water, collagen, glycoproteins, etc. For example, increased glucosaminoglycan content leads to an increase in compressive stiffness, and increased water content leads to a lower aggregate modulus.

Tendon-bone interface

[edit]In addition to its role in load-bearing joints, cartilage serves a crucial function as a gradient material between softer tissues and bone. Mechanical gradients are crucial for your body's function, and for complex artificial structures including joint implants. Interfaces with mismatched material properties lead to areas of high stress concentration which, over the millions of loading cycles experienced by human joins over a lifetime, would eventually lead to failure. For example, the elastic modulus of human bone is roughly 20 GPa while the softer regions of cartilage can be about 0.5 to 0.9 MPa.[16][17] When there is a smooth gradient of materials properties, however, stresses are distributed evenly across the interface, which puts less wear on each individual part.

The body solves this problem with stiffer, higher modulus layers near bone, with high concentrations of mineral deposits such as hydroxyapatite. Collagen fibers (which provide mechanical stiffness in cartilage) in this region are anchored directly to bones, reducing the possible deformation. Moving closer to soft tissue into the region known as the tidemark, the density of chondrocytes increases and collagen fibers are rearranged to optimize for stress dissipation and low friction. The outermost layer near the articular surface is known as the superficial zone, which primarily serves as a lubrication region. Here cartilage is characterized by a dense extracellular matrix and is rich in proteoglycans (which dispel and reabsorb water to soften impacts) and thin collagen oriented parallel to the joint surface which have excellent shear resistant properties.[18]

Osteoarthritis and natural aging both have negative effects on cartilage as a whole as well as the proper function of the materials gradient within. The earliest changes are often in the superficial zone, the softest and most lubricating part of the tissue. Degradation of this layer can put additional stresses on deeper layers which are not designed to support the same deformations. Another common effect of aging is increased crosslinking of collagen fibers. This leads to stiffer cartilage as a whole, which again can lead to early failure as stiffer tissue is more susceptible to fatigue based failure. Aging in calcified regions also generally leads to a larger number of mineral deposits, which has a similarly undesired stiffening effect.[19] Osteoarthritis has more extreme effects and can entirely wear down cartilage, causing direct bone-to-bone contact.[20]

Frictional properties

[edit]Lubricin, a glycoprotein abundant in cartilage and synovial fluid, plays a major role in bio-lubrication and wear protection of cartilage.[21]

Repair

[edit]Cartilage has limited repair capabilities: Because chondrocytes are bound in lacunae, they cannot migrate to damaged areas. Therefore, cartilage damage is difficult to heal. Also, because hyaline cartilage does not have a blood supply, the deposition of new matrix is slow. Over the last years, surgeons and scientists have elaborated a series of cartilage repair procedures that help to postpone the need for joint replacement. A tear of the meniscus of the knee cartilage can often be surgically trimmed to reduce problems. Complete healing of cartilage after injury or repair procedures is hindered by cartilage-specific inflammation caused by the involvement of M1/M2 macrophages, mast cells, and their intercellular interactions.[22]

Biological engineering techniques are being developed to generate new cartilage, using a cellular "scaffolding" material and cultured cells to grow artificial cartilage.[23] Extensive researches have been conducted on freeze-thawed PVA hydrogels as a base material for such a purpose.[24] These gels have exhibited great promises in terms of biocompatibility, wear resistance, shock absorption, friction coefficient, flexibility, and lubrication, and thus are considered superior to polyethylene-based cartilages. A two-year implantation of the PVA hydrogels as artificial meniscus in rabbits showed that the gels remain intact without degradation, fracture, or loss of properties.[24]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Disease

[edit]Several diseases can affect cartilage. Chondrodystrophies are a group of diseases, characterized by the disturbance of growth and subsequent ossification of cartilage. Some common diseases that affect the cartilage are listed below.

- Osteoarthritis: Osteoarthritis is a disease of the whole joint, however, one of the most affected tissues is the articular cartilage. The cartilage covering bones (articular cartilage—a subset of hyaline cartilage) is thinned, eventually completely wearing away, resulting in a "bone against bone" within the joint, leading to reduced motion, and pain. Osteoarthritis affects the joints exposed to high stress and is therefore considered the result of "wear and tear" rather than a true disease. It is treated by arthroplasty, the replacement of the joint by a synthetic joint often made of a stainless steel alloy (cobalt chromoly) and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene. Chondroitin sulfate or glucosamine sulfate supplements, have been claimed to reduce the symptoms of osteoarthritis, but there is little good evidence to support this claim.[25] In osteoarthritis, increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines cause aberrant changes in differentiated chondrocytes function which leads to an excess of chondrocyte catabolic activity, mediated by factors including matrix metalloproteinases and aggrecanases.[26]

- Traumatic rupture or detachment: The cartilage in the knee is frequently damaged but can be partially repaired through knee cartilage replacement therapy. Often when athletes talk of damaged "cartilage" in their knee, they are referring to a damaged meniscus (a fibrocartilage structure) and not the articular cartilage.

- Achondroplasia: Reduced proliferation of chondrocytes in the epiphyseal plate of long bones during infancy and childhood, resulting in dwarfism.

- Costochondritis: Inflammation of cartilage in the ribs, causing chest pain.

- Spinal disc herniation: Asymmetrical compression of an intervertebral disc ruptures the sac-like disc, causing a herniation of its soft content. The hernia often compresses the adjacent nerves and causes back pain.

- Relapsing polychondritis: a destruction, probably autoimmune, of cartilage, especially of the nose and ears, causing disfiguration. Death occurs by asphyxiation as the larynx loses its rigidity and collapses.

Tumors made up of cartilage tissue, either benign or malignant, can occur. They usually appear in bone, rarely in pre-existing cartilage. The benign tumors are called chondroma, the malignant ones chondrosarcoma. Tumors arising from other tissues may also produce a cartilage-like matrix, the best-known being pleomorphic adenoma of the salivary glands.

The matrix of cartilage acts as a barrier, preventing the entry of lymphocytes or diffusion of immunoglobulins. This property allows for the transplantation of cartilage from one individual to another without fear of tissue rejection.

Imaging

[edit]Cartilage does not absorb X-rays under normal in vivo conditions, but a dye can be injected into the synovial membrane that will cause the X-rays to be absorbed by the dye. The resulting void on the radiographic film between the bone and meniscus represents the cartilage. For in vitro X-ray scans, the outer soft tissue is most likely removed, so the cartilage and air boundary are enough to contrast the presence of cartilage due to the refraction of the X-ray.[27]

Other animals

[edit]Cartilaginous fish

[edit]Cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) or sharks, rays and chimaeras have a skeleton composed entirely of cartilage.

Invertebrate cartilage

[edit]Cartilage tissue can also be found among some arthropods such as horseshoe crabs, some mollusks such as marine snails and cephalopods, and some annelids like sabellid polychaetes.

Arthropods

[edit]The most studied cartilage in arthropods is the branchial cartilage of Limulus polyphemus. It is a vesicular cell-rich cartilage due to the large, spherical and vacuolated chondrocytes with no homologies in other arthropods. Other type of cartilage found in L. polyphemus is the endosternite cartilage, a fibrous-hyaline cartilage with chondrocytes of typical morphology in a fibrous component, much more fibrous than vertebrate hyaline cartilage, with mucopolysaccharides immunoreactive against chondroitin sulfate antibodies. There are homologous tissues to the endosternite cartilage in other arthropods.[28] The embryos of Limulus polyphemus express ColA and hyaluronan in the gill cartilage and the endosternite, which indicates that these tissues are fibrillar-collagen-based cartilage. The endosternite cartilage forms close to Hh-expressing ventral nerve cords and expresses ColA and SoxE, a Sox9 analog. This is also seen in gill cartilage tissue.[29]

Mollusks

[edit]In cephalopods, the models used for the studies of cartilage are Octopus vulgaris and Sepia officinalis. The cephalopod cranial cartilage is the invertebrate cartilage that shows more resemblance to the vertebrate hyaline cartilage. The growth is thought to take place throughout the movement of cells from the periphery to the center. The chondrocytes present different morphologies related to their position in the tissue.[28] The embryos of S. officinalis express ColAa, ColAb, and hyaluronan in the cranial cartilages and other regions of chondrogenesis. This implies that the cartilage is fibrillar-collagen-based. The S. officinalis embryo expresses hh, whose presence causes ColAa and ColAb expression and is also able to maintain proliferating cells undiferentiated. It has been observed that this species presents the expression SoxD and SoxE, analogs of the vertebrate Sox5/6 and Sox9, in the developing cartilage. The cartilage growth pattern is the same as in vertebrate cartilage.[29]

In gastropods, the interest lies in the odontophore, a cartilaginous structure that supports the radula. The most studied species regarding this particular tissue is Busycotypus canaliculatus. The odontophore is a vesicular cell rich cartilage, consisting of vacuolated cells containing myoglobin, surrounded by a low amount of extra cellular matrix containing collagen. The odontophore contains muscle cells along with the chondrocytes in the case of Lymnaea and other mollusks that graze vegetation.[28]

Sabellid polychaetes

[edit]The sabellid polychaetes, or feather duster worms, have cartilage tissue with cellular and matrix specialization supporting their tentacles. They present two distinct extracellular matrix regions. These regions are an acellular fibrous region with a high collagen content, called cartilage-like matrix, and collagen lacking a highly cellularized core, called osteoid-like matrix. The cartilage-like matrix surrounds the osteoid-like matrix. The amount of the acellular fibrous region is variable. The model organisms used in the study of cartilage in sabellid polychaetes are Potamilla species and Myxicola infundibulum.[28]

Plants and fungi

[edit]Vascular plants, particularly seeds, and the stems of some mushrooms, are sometimes called "cartilaginous", although they contain no cartilage.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Sophia Fox, AJ; Bedi, A; Rodeo, SA (November 2009). "The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function". Sports Health. 1 (6): 461–8. doi:10.1177/1941738109350438. PMC 3445147. PMID 23015907.

- ^ de Buffrénil, Vivian; de Ricqlès, Armand J; Zylberberg, Louise; Padian, Kevin; Laurin, Michel; Quilhac, Alexandra (2021). Vertebrate skeletal histology and paleohistology (Firstiton ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. xii + 825. ISBN 978-1-351-18957-6.

- ^ Buffrénil, Vivian de; Quilhac, Alexandra (2021). "An Overview of the Embryonic Development of the Bony Skeleton". Vertebrate Skeletal Histology and Paleohistology. CRC Press: 29–38. doi:10.1201/9781351189590-2. ISBN 978-1-351-18959-0. S2CID 236422314.

- ^ Quilhac, Alexandra (2021). "An Overview of Cartilage Histology". Vertebrate Skeletal Histology and Paleohistology. CRC Press: 123–146. doi:10.1201/9781351189590-7. ISBN 978-1-351-18959-0. S2CID 236413810.

- ^ Cervantes-Diaz, Fret; Contreras, Pedro; Marcellini, Sylvain (March 2017). "Evolutionary origin of endochondral ossification: the transdifferentiation hypothesis". Development Genes and Evolution. 227 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1007/s00427-016-0567-y. PMID 27909803. S2CID 21024809.

- ^ Asanbaeva A, Masuda K, Thonar EJ, Klisch SM, Sah RL (January 2008). "Cartilage growth and remodeling: modulation of balance between proteoglycan and collagen network in vitro with beta-aminopropionitrile". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 16 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.05.019. PMID 17631390.

- ^ Razmara E, Bitaraf A, Yousefi H, Nguyen TH, Garshasbi M, Cho WC, Babashah S (September 2019). "Non-Coding RNAs in Cartilage Development: An Updated Review". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (18): 4475. doi:10.3390/ijms20184475. PMC 6769748. PMID 31514268.

- ^ Chremos A, Horkay F (September 2023). "Coexistence of Crumpling and Flat Sheet Conformations in Two-Dimensional Polymer Networks: An Understanding of Aggrecan Self-Assembly". Physical Review Letters. 131 (13) 138101. Bibcode:2023PhRvL.131m8101C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.138101. PMID 37832020. S2CID 263252529.

- ^ Asanbaeva A, Tam J, Schumacher BL, Klisch SM, Masuda K, Sah RL (June 2008). "Articular cartilage tensile integrity: modulation by matrix depletion is maturation-dependent". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 474 (1): 175–82. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.012. PMC 2440786. PMID 18394422.

- ^ Hayes WC, Mockros LF (October 1971). "Viscoelastic properties of human articular cartilage" (PDF). Journal of Applied Physiology. 31 (4): 562–8. doi:10.1152/jappl.1971.31.4.562. PMID 5111002.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mansour, J. M. (2013). Biomechanics of Cartilage. pp. 69–83.

- ^ a b c Patel, J. M.; Wise, B. C.; Bonnevie, E. D.; Mauck, R. L. (2019). "A Systematic Review and Guide to Mechanical Testing for Articular Cartilage Tissue Engineering". Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 25 (10): 593–608. doi:10.1089/ten.tec.2019.0116. PMC 6791482. PMID 31288616.

- ^ a b Korhonen, R. K.; Laasanen, M. S.; Töyräs, J.; Rieppo, J.; Hirvonen, J.; Helminen, H. J.; Jurvelin, J. S. (2002). "Comparison of the Equilibrium Response of Articular Cartilage in Unconfined Compression, Confined Compression and Indentation". Journal of Biomechanics. 35 (7): 903–909. doi:10.1016/S0021-9290(02)00052-0. PMID 12052392.

- ^ a b Kabir, W.; Di Bella, C.; Choong, P. F. M.; O'Connell, C. D. (2021). "Assessment of Native Human Articular Cartilage: A Biomechanical Protocol". Cartilage. 13 (2 Suppl): 427S – 437S. doi:10.1177/1947603520973240. PMC 8804788. PMID 33218275.

- ^ Jin, H.; Lewis, J. L. (2004). "Determination of Poisson's Ratio of Articular Cartilage by Indentation Using Different-Sized Indenters". Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 126 (2): 138–145. doi:10.1115/1.1688772. PMID 15179843.

- ^ Handorf, Andrew (27 April 2015). "Tissue Stiffness Dictates Development, Homeostasis, and Disease Progression". Organogensis. 11 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/15476278.2015.1019687. PMC 4594591. PMID 25915734.

- ^ Mansour, Joseph. Biomechanics of Cartilage (PDF). MDPI. pp. 66–79.

- ^ Chen, Li (6 February 2023). "Preparation and Characterization of Biomimetic Functional Scaffold with Gradient Structure for Osteochondral Defect Repair". Bioengineering. 10 (2): 213. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10020213. PMC 9952804. PMID 36829707.

- ^ Lotz, Martin (28 March 2012). "Effects of aging on articular cartilage homeostasis". Bone. 51 (2): 241–248. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.023. PMC 3372644. PMID 22487298.

- ^ "Osteoarthritis". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Rhee DK, Marcelino J, Baker M, Gong Y, Smits P, Lefebvre V, et al. (March 2005). "The secreted glycoprotein lubricin protects cartilage surfaces and inhibits synovial cell overgrowth". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 115 (3): 622–31. doi:10.1172/JCI22263. PMC 548698. PMID 15719068.

- ^ Klabukov, I.; Atiakshin, D.; Kogan, E.; Ignatyuk, M.; Krasheninnikov, M.; Zharkov, N.; Yakimova, A.; Grinevich, V.; Pryanikov, P.; Parshin, V.; Sosin, D.; Kostin, A.A.; Shegay, P.; Kaprin, A.D.; Baranovskii, D. (2023). "Post-Implantation Inflammatory Responses to Xenogeneic Tissue-Engineered Cartilage Implanted in Rabbit Trachea: The Role of Cultured Chondrocytes in the Modification of Inflammation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (23) 16783. doi:10.3390/ijms242316783. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 10706106. PMID 38069106.

- ^ International Cartilage Repair Society ICRS

- ^ a b Adelnia, Hossein; Ensandoost, Reza; Shebbrin Moonshi, Shehzahdi; Gavgani, Jaber Nasrollah; Vasafi, Emad Izadi; Ta, Hang Thu (2022-02-05). "Freeze/thawed polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels: Present, past and future". European Polymer Journal. 164 110974. Bibcode:2022EurPJ.16410974A. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110974. hdl:10072/417476. ISSN 0014-3057. S2CID 245576810.

- ^ "Supplements for osteoarthritis 'do not work'". BBC News. 16 September 2010.

- ^ Ansari, Mohammad Y.; Ahmad, Nashrah; Haqqi, Tariq M. (2018-09-05). "Butein Activates Autophagy Through AMPK/TSC2/ULK1/mTOR Pathway to Inhibit IL-6 Expression in IL-1β Stimulated Human Chondrocytes". Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 49 (3): 932–946. doi:10.1159/000493225. ISSN 1015-8987. PMID 30184535. S2CID 52166938.

- ^ Osteoarthritis Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine. Osteoarthritis.about.com. Retrieved on 2015-10-26.

- ^ a b c d Cole AG, Hall BK (2004). "The nature and significance of invertebrate cartilages revisited: distribution and histology of cartilage and cartilage-like tissues within the Metazoa". Zoology. 107 (4): 261–73. Bibcode:2004Zool..107..261C. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2004.05.001. PMID 16351944.

- ^ a b Tarazona OA, Slota LA, Lopez DH, Zhang G, Cohn MJ (May 2016). "The genetic program for cartilage development has deep homology within Bilateria". Nature. 533 (7601): 86–9. Bibcode:2016Natur.533...86T. doi:10.1038/nature17398. PMID 27111511. S2CID 3932905.

- ^ Eflora – Glossary. University of Sydney (2010-06-16). Retrieved on 2015-10-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Keller-Peck C (2008). Vertebrate Histology, ZOOL 400. Boise State University.

External links

[edit]- Cartilage.org, International Cartilage Regeneration & Joint Preservation Society

- KUMC.edu Archived 2011-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, Cartilage tutorial, University of Kansas Medical Center

- Bartleby.com, text from Gray's anatomy

- MadSci.org, I've heard 'Ears and nose do not ever stop growing.' Is this false?

- CartilageHealth.com, Information on Articular Cartilage Injury Prevention, Repair and Rehabilitation

- About.com Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, Osteoarthritis

- Cartilage types

- Different cartilages on TheFreeDictionary

- Cartilage photomicrographs