Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Skull

View on Wikipedia

| Skull | |

|---|---|

Volume rendering of a mouse skull | |

| Details | |

| System | Skeletal system |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D012886 |

| FMA | 54964 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate.[1][2] In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent parts: the neurocranium and the facial skeleton,[3] which evolved from the first pharyngeal arch. The skull forms the frontmost portion of the axial skeleton and is a product of cephalization and vesicular enlargement of the brain, with several special senses structures such as the eyes, ears, nose, tongue and, in fish, specialized tactile organs such as barbels near the mouth.[4]

The skull is composed of three types of bone: cranial bones, facial bones and ossicles, which is made up of a number of fused flat and irregular bones. The cranial bones are joined at firm fibrous junctions called sutures and contains many foramina, fossae, processes, and sinuses. In zoology, the openings in the skull are called fenestrae, the most prominent of which is the foramen magnum, where the brainstem goes through to join the spinal cord.

In human anatomy, the neurocranium (or braincase), is further divided into the calvaria and the endocranium, together forming a cranial cavity that houses the brain. The interior periosteum forms part of the dura mater, the facial skeleton and splanchnocranium with the mandible being its largest bone. The mandible articulates with the temporal bones of the neurocranium at the paired temporomandibular joints. The skull itself articulates with the spinal column at the atlanto-occipital joint. The human skull fully develops two years after birth.

Functions of the skull include physical protection for the brain, providing attachments for neck muscles, facial muscles and muscles of mastication, providing fixed eye sockets and outer ears (ear canals and auricles) to enable stereoscopic vision and sound localisation, forming nasal and oral cavities that allow better olfaction, taste and digestion, and contributing to phonation by acoustic resonance within the cavities and sinuses. In some animals such as ungulates and elephants, the skull also has a function in anti-predator defense and sexual selection by providing the foundation for horns, antlers and tusks.

The English word skull is probably derived from Old Norse skulle,[5] while the Latin word cranium comes from the Greek root κρανίον (kranion).

Structure

[edit]Humans

[edit]

The human skull is the bone structure that forms the head in the human skeleton. It supports the structures of the face and forms a cavity for the brain. Like the skulls of other vertebrates, it protects the brain from injury.[6]

The skull consists of three parts, of different embryological origin—the neurocranium, the sutures, and the facial skeleton. The neurocranium (or braincase) forms the protective cranial cavity that surrounds and houses the brain and brainstem.[7] The upper areas of the cranial bones form the calvaria (skullcap). The facial skeleton (membranous viscerocranium) is formed by the bones supporting the face, and includes the mandible.

The bones of the skull are joined by fibrous joints known as sutures—synarthrodial (immovable) joints formed by bony ossification, with Sharpey's fibres permitting some flexibility. Sometimes there can be extra bone pieces within the suture known as Wormian bones or sutural bones. Most commonly these are found in the course of the lambdoid suture.

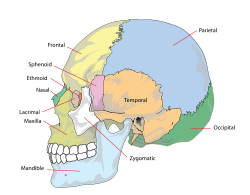

Bones

[edit]The human skull is generally considered to consist of 22 bones—eight cranial bones and fourteen facial skeleton bones. In the neurocranium these are the occipital bone, two temporal bones, two parietal bones, the sphenoid, ethmoid and frontal bones.

The bones of the facial skeleton (14) are the vomer, two inferior nasal conchae, two nasal bones, two maxilla, the mandible, two palatine bones, two zygomatic bones, and two lacrimal bones. Some sources count a paired bone as one, or the maxilla as having two bones (as its parts); some sources include the hyoid bone or the three ossicles of the middle ear, the malleus, incus, and stapes, but the overall general consensus of the number of bones in the human skull is the stated twenty-two.

Some of these bones—the occipital, parietal, frontal, in the neurocranium, and the nasal, lacrimal, and vomer, in the facial skeleton are flat bones.

Cavities and foramina

[edit]

The skull also contains sinuses, air-filled cavities known as paranasal sinuses, and numerous foramina. The sinuses are lined with respiratory epithelium. Their known functions are the lessening of the weight of the skull, the aiding of resonance to the voice and the warming and moistening of the air drawn into the nasal cavity.

The foramina are openings in the skull. The largest of these is the foramen magnum, of the occipital bone, that allows the passage of the spinal cord as well as nerves and blood vessels.

Processes

[edit]The many processes of the skull include the mastoid process and the zygomatic processes.

Other vertebrates

[edit]Fenestrae

[edit]

|

The fenestrae (from Latin, meaning windows) are openings in the skull.

|

Bones

[edit]The jugal is a skull bone that found in most of the reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the zygomatic bone or malar bone.[8]

The prefrontal bone is a bone that separates the lacrimal and frontal bones in many tetrapod skulls.

Fish

[edit]

The skull of fish is formed from a series of only loosely connected bones. Lampreys and sharks only possess a cartilaginous endocranium, with both the upper jaw and the lower jaws being separate elements. Bony fishes have additional dermal bone, forming a more or less coherent skull roof in lungfish and holost fish. The lower jaw defines the chin.

The simpler structure is found in jawless fish, in which the cranium is normally represented by a trough-like basket of cartilaginous elements only partially enclosing the brain, and associated with the capsules for the inner ears and the single nostril. Distinctively, these fish have no jaws.[9]

Cartilaginous fish, such as sharks and rays, have also simple, and presumably primitive, skull structures. The cranium is a single structure forming a case around the brain, enclosing the lower surface and the sides, but always at least partially open at the top as a large fontanelle. The most anterior part of the cranium includes a forward plate of cartilage, the rostrum, and capsules to enclose the olfactory organs. Behind these are the orbits, and then an additional pair of capsules enclosing the structure of the inner ear. Finally, the skull tapers towards the rear, where the foramen magnum lies immediately above a single condyle, articulating with the first vertebra. There are, in addition, at various points throughout the cranium, smaller foramina for the cranial nerves. The jaws consist of separate hoops of cartilage, almost always distinct from the cranium proper.[9]

In ray-finned fish, there has also been considerable modification from the primitive pattern. The roof of the skull is generally well formed, and although the exact relationship of its bones to those of tetrapods is unclear, they are usually given similar names for convenience. Other elements of the skull, however, may be reduced; there is little cheek region behind the enlarged orbits, and little, if any bone in between them. The upper jaw is often formed largely from the premaxilla, with the maxilla itself located further back, and an additional bone, the symplectic, linking the jaw to the rest of the cranium.[10]

Although the skulls of fossil lobe-finned fish resemble those of the early tetrapods, the same cannot be said of those of the living lungfishes. The skull roof is not fully formed, and consists of multiple, somewhat irregularly shaped bones with no direct relationship to those of tetrapods. The upper jaw is formed from the pterygoids and vomers alone, all of which bear teeth. Much of the skull is formed from cartilage, and its overall structure is reduced.[10]

Tetrapods

[edit]The skulls of the earliest tetrapods closely resembled those of their ancestors amongst the lobe-finned fishes. The skull roof is formed of a series of plate-like bones, including the maxilla, frontals, parietals, and lacrimals, among others. It is overlaying the endocranium, corresponding to the cartilaginous skull in sharks and rays. The various separate bones that compose the temporal bone of humans are also part of the skull roof series. A further plate composed of four pairs of bones forms the roof of the mouth; these include the vomer and palatine bones. The base of the cranium is formed from a ring of bones surrounding the foramen magnum and a median bone lying further forward; these are homologous with the occipital bone and parts of the sphenoid in mammals. Finally, the lower jaw is composed of multiple bones, only the most anterior of which (the dentary) is homologous with the mammalian mandible.[10]

In living tetrapods, a great many of the original bones have either disappeared or fused into one another in various arrangements.

Birds

[edit]

Birds have a diapsid skull, as in reptiles, with a prelacrimal fossa (present in some reptiles). The skull has a single occipital condyle.[11] The skull consists of five major bones: the frontal (top of head), parietal (back of head), premaxillary and nasal (top beak), and the mandible (bottom beak). The skull of a normal bird usually weighs about 1% of the bird's total bodyweight. The eye occupies a considerable amount of the skull and is surrounded by a sclerotic eye-ring, a ring of tiny bones. This characteristic is also seen in reptiles.

Amphibians

[edit]

Living amphibians typically have greatly reduced skulls, with many of the bones either absent or wholly or partly replaced by cartilage.[10] In mammals and birds, in particular, modifications of the skull occurred to allow for the expansion of the brain. The fusion between the various bones is especially notable in birds, in which the individual structures may be difficult to identify.

Development

[edit]

The skull is a complex structure; its bones are formed both by intramembranous and endochondral ossification. The skull roof bones, comprising the bones of the facial skeleton and the sides and roof of the neurocranium, are dermal bones formed by intramembranous ossification, though the temporal bones are formed by endochondral ossification. The endocranium, the bones supporting the brain (the occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid) are largely formed by endochondral ossification. Thus frontal and parietal bones are purely membranous.[12] The geometry of the skull base and its fossae, the anterior, middle and posterior cranial fossae changes rapidly. The anterior cranial fossa changes especially during the first trimester of pregnancy and skull defects can often develop during this time.[13] The prenatal growth of the anterior cranial fossa is not uniform. During the first trimester, there is allometric growth, with the longitudinal dimension increasing from 5 to 17 millimeters between the 8th and 14th week of fetal life. At the same time, the angle of the anterior cranial fossa decreases, and its depth increases towards the middle cranial fossa. In the second trimester, growth continues but becomes more uniform, with only slight changes in the angle of the anterior cranial fossa. There is a gradual decrease in the angle between the lesser wings of the sphenoid bone as the depth of the anterior cranial fossa increases in the frontal plane.[14]

At birth, the human skull is made up of 44 separate bony elements. During development, many of these bony elements gradually fuse together into solid bone (for example, the frontal bone). The bones of the roof of the skull are initially separated by regions of dense connective tissue called fontanelles. There are six fontanelles: one anterior (or frontal), one posterior (or occipital), two sphenoid (or anterolateral), and two mastoid (or posterolateral). At birth, these regions are fibrous and moveable, necessary for birth and later growth. This growth can put a large amount of tension on the "obstetrical hinge", which is where the squamous and lateral parts of the occipital bone meet. A possible complication of this tension is rupture of the great cerebral vein. As growth and ossification progress, the connective tissue of the fontanelles is invaded and replaced by bone creating sutures. The five sutures are the two squamous sutures, one coronal, one lambdoid, and one sagittal suture. The posterior fontanelle usually closes by eight weeks, but the anterior fontanel can remain open up to eighteen months. The anterior fontanelle is located at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones; it is a "soft spot" on a baby's forehead. Careful observation will show that you can count a baby's heart rate by observing the pulse pulsing softly through the anterior fontanelle.

The skull in the neonate is large in proportion to other parts of the body. The facial skeleton is one seventh of the size of the calvaria. (In the adult it is half the size). The base of the skull is short and narrow, though the inner ear is almost adult size.[15]

Clinical significance

[edit]Craniosynostosis is a condition in which one or more of the fibrous sutures in an infant skull prematurely fuses,[16] and changes the growth pattern of the skull.[17] Because the skull cannot expand perpendicular to the fused suture, it grows more in the parallel direction.[17] Sometimes the resulting growth pattern provides the necessary space for the growing brain, but results in an abnormal head shape and abnormal facial features.[17] In cases in which the compensation does not effectively provide enough space for the growing brain, craniosynostosis results in increased intracranial pressure leading possibly to visual impairment, sleeping impairment, eating difficulties, or an impairment of mental development.[18]

A copper beaten skull is a phenomenon wherein intense intracranial pressure disfigures the internal surface of the skull.[19] The name comes from the fact that the inner skull has the appearance of having been beaten with a ball-peen hammer, such as is often used by coppersmiths. The condition is most common in children.

Injuries and treatment

[edit]Injuries to the brain can be life-threatening. Normally the skull protects the brain from damage through its high resistance to deformation; the skull is one of the least deformable structures found in nature, needing the force of about 1 ton to reduce its diameter by 1 cm.[20] In some cases of head injury, however, there can be raised intracranial pressure through mechanisms such as a subdural haematoma. In these cases, the raised intracranial pressure can cause herniation of the brain out of the foramen magnum ("coning") because there is no space for the brain to expand; this can result in significant brain damage or death unless an urgent operation is performed to relieve the pressure. This is why patients with concussion must be watched extremely carefully. Repeated concussions can activate the structure of skull bones as the brain's protective covering.[21]

Dating back to Neolithic times, a skull operation called trepanning was sometimes performed. This involved drilling a burr hole in the cranium. Examination of skulls from this period reveals that the patients sometimes survived for many years afterward. It seems likely that trepanning was also performed purely for ritualistic or religious reasons. Nowadays this procedure is still used but is normally called a craniectomy.

In March 2013, for the first time in the U.S., researchers replaced a large percentage of a patient's skull with a precision, 3D-printed polymer implant.[22] About 9 months later, the first complete cranium replacement with a 3D-printed plastic insert was performed on a Dutch woman. She had been suffering from hyperostosis, which increased the thickness of her skull and compressed her brain.[23]

A study conducted in 2018 by the researchers of Harvard Medical School in Boston, funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH), suggested that instead of travelling via blood, there are "tiny channels" in the skull through which the immune cells combined with the bone marrow reach the areas of inflammation after an injury to the brain tissues.[24]

Transgender procedures

[edit]Surgical alteration of sexually dimorphic skull features may be carried out as a part of facial feminization surgery or facial masculinization surgery, these reconstructive surgical procedures that can alter sexually dimorphic facial features to bring them closer in shape and size to facial features of the desired sex.[25][26] These procedures can be an important part of the treatment of transgender people for gender dysphoria.[27][28]

Society and culture

[edit]

Artificial cranial deformation is a largely historical practice of some cultures. Cords and wooden boards would be used to apply pressure to an infant's skull and alter its shape, sometimes quite significantly. This procedure would begin just after birth and would be carried on for several years.[citation needed]

Osteology

[edit]Like the face, the skull and teeth can also indicate a person's life history and origin. Forensic scientists and archaeologists use quantitative and qualitative traits to estimate what the bearer of the skull looked like. When a significant amount of bones are found, such as at Spitalfields in the UK and Jōmon shell mounds in Japan, osteologists can use traits, such as the proportions of length, height and width, to know the relationships of the population of the study with other living or extinct populations.[citation needed]

The German physician Franz Joseph Gall in around 1800 formulated the theory of phrenology, which attempted to show that specific features of the skull are associated with certain personality traits or intellectual capabilities of its owner. His theory is now considered to be pseudoscientific.[citation needed]

Sexual dimorphism

[edit]In the mid-nineteenth century, anthropologists found it crucial to distinguish between male and female skulls. An anthropologist of the time, James McGrigor Allan, argued that the female brain was similar to that of an animal.[29] This allowed anthropologists to declare that women were in fact more emotional and less rational than men. McGrigor then concluded that women's brains were more analogous to infants, thus deeming them inferior at the time.[29] To further these claims of female inferiority and silence the feminists of the time, other anthropologists joined in on the studies of the female skull. These cranial measurements are the basis of what is known as craniology. These cranial measurements were also used to draw a connection between women and black people.[29]

Research has shown that while in early life there is little difference between male and female skulls, in adulthood male skulls tend to be larger and more robust than female skulls, which are lighter and smaller, with a cranial capacity about 10 percent less than that of the male.[30] However, later studies show that women's skulls are slightly thicker and thus men may be more susceptible to head injury than women.[31] However, other studies shows that men's skulls are slightly thicker in certain areas.[32] Some studies show that females are more susceptible to concussion than males.[33] Men's skulls have also been shown to maintain density with age, which may aid in preventing head injury, while women's skull density slightly decreases with age.[34][35]

Male skulls can all have more prominent supraorbital ridges, glabella, and temporal lines. Female skulls generally have rounder orbits and narrower jaws. Male skulls on average have larger, broader palates, squarer orbits, larger mastoid processes, larger sinuses, and larger occipital condyles than those of females. Male mandibles typically have squarer chins and thicker, rougher muscle attachments than female mandibles.[36]

Craniometry

[edit]The cephalic index is the ratio of the width of the head, multiplied by 100 and divided by its length (front to back). The index is also used to categorize animals, especially dogs and cats. The width is usually measured just below the parietal eminence, and the length from the glabella to the occipital point.

Humans may be:

- Dolichocephalic — long-headed

- Mesaticephalic — medium-headed

- Brachycephalic — short-headed[15]

The vertical cephalic index refers to the ratio between the height of the head multiplied by 100 and divided by the length of the head.

Humans may be:

- Chamaecranic — low-skulled

- Orthocranic — medium high-skulled

- Hypsicranic — high-skulled

Terminology

[edit]- Chondrocranium, a primitive cartilaginous skeletal structure

- Endocranium

- Epicranium

- Pericranium, a membrane that lines the outer surface of the cranium

History

[edit]Trepanning, a practice in which a hole is created in the skull, has been described as the oldest surgical procedure for which there is archaeological evidence,[37] found in the forms of cave paintings and human remains. At one burial site in France dated to 6500 BCE, 40 out of 120 prehistoric skulls found had trepanation holes.[38]

Additional images

[edit]-

African elephant skull in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History

-

Vulture skull

-

King cobra skull

-

Goat skull

-

Skull of Tiktaalik, an extinct genus transitional between lobe-finned fish and early tetrapods

-

Centrosaurus skull

See also

[edit]- Craniometry

- Crystal skull

- Head and neck anatomy

- Human skull symbolism

- Memento mori

- Plagiocephaly, the abnormal flattening of one side of the skull

- Skull and crossbones (disambiguation)

- Teshik-Tash

- Totenkopf

- Yorick

- Overmodelled skull

- Diploë

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 128 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 128 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

As of this edit, this article uses content from "Morphometric evaluation of the anterior cranial fossa during the prenatal stage in humans and its clinical implications", authored by Wojciech Derkowski, Alicja Kędzia, Krzysztof Dudek, Michał Glonek, which is licensed in a way that permits reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, but not under the GFDL. All relevant terms must be followed.

- ^ "Cranium". www.cancer.gov. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ "Thesaurus results for Skull". www.merriam-webster.com. 21 November 2024. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ White, Tim D.; Black, Michael T.; Folkens, Pieter Arend (21 January 2011). Human Osteology (3rd ed.). Academic Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-08-092085-6.

- ^ "Cephalization: Biology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ "Definition of skull | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Alcamo, I. Edward (2003). Anatomy Coloring Workbook. The Princeton Review. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-375-76342-7.

- ^ Mansour, Salah; Magnan, Jacques; Ahmad, Hassan Haidar; Nicolas, Karen; Louryan, Stéphane (2019). Comprehensive and Clinical Anatomy of the Middle Ear. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-030-15363-2.

- ^ Dechow, Paul C.; Wang, Qian (January 2017). "Evolution of the Jugal/Zygomatic Bones". The Anatomical Record. 300 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1002/ar.23519. PMID 28000397.

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Thomas S., Parsons (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 173–177. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ a b c d Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 216–247. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Wing, Leonard W. (1956). "The Place of Birds in Nature". Natural History of Birds. The Ronald Press Company. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Carlson, Bruce M. (1999). Human Embryology & Developmental Biology (Second ed.). Mosby. pp. 166–170. ISBN 0-8151-1458-3.

- ^ Derkowski, Wojciech; Kędzia, Alicja; Glonek, Michał (2003). "Clinical anatomy of the human anterior cranial fossa during the prenatal period". Folia Morphologica. 62 (3): 271–3. PMID 14507064. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011.

- ^ Derkowski, Wojciech; Kędzia, Alicja; Dudek, Krzysztof; Glonek, Michał (27 December 2024). "Morphometric evaluation of the anterior cranial fossa during the prenatal stage in humans and its clinical implications". PLOS ONE. 19 (12) e0309184. Bibcode:2024PLoSO..1909184D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0309184. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 11676864. PMID 39729454.

- ^ a b Chaurasia, B. D. (2013). BD Chaurasia's Human Anatomy: Regional and Applied Dissection and Clinical. Vol. 3: Head–Neck Brain (Sixth ed.). CBS Publishers & Distributors. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-81-239-2332-1.

- ^ Silva, Sandra; Jeanty, Philippe (7 June 1999). "Cloverleaf skull or kleeblattschadel". TheFetus.net. MacroMedia. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- ^ a b c Slater, Bethany J.; Lenton, Kelly A.; Kwan, Matthew D.; Gupta, Deepak M.; Wan, Derrick C.; Longaker, Michael T. (April 2008). "Cranial Sutures: A Brief Review". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 121 (4): 170e – 8e. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000304441.99483.97. PMID 18349596. S2CID 34344899.

- ^ Gault, David T.; Renier, Dominique; Marchac, Daniel; Jones, Barry M. (September 1992). "Intracranial Pressure and Intracranial Volume in Children with Craniosynostosis". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 90 (3): 377–81. doi:10.1097/00006534-199209000-00003. PMID 1513883.

- ^ Gaillard, Frank. "Copper beaten skull". Radiopaedia. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Holbourn, A. H. S. (9 October 1943). "Mechanics of Head Injuries". The Lancet. 242 (6267): 438–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)87453-X.

- ^ "Repeated Concussions Can Thicken the Skull". 2 September 2022.

- ^ "3D-Printed Polymer Skull Implant Used For First Time in US". Medical Daily. 7 March 2013. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ "Dutch hospital gives patient new plastic skull, made by 3D printer". DutchNews.nl. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ^ Cohut, Maria (29 August 2018). "Newly discovered skull channels play role in immunity". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Ainsworth, Tiffiny A.; Spiegel, Jeffrey H. (2010). "Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery". Quality of Life Research. 19 (7): 1019–24. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9668-7. PMID 20461468. S2CID 601504.

- ^ Shams, Mohammad Ghasem; Motamedi, Mohammad Hosein Kalantar (9 January 2009). "Case report: Feminizing the male face". ePlasty. 9: e2. PMC 2627308. PMID 19198644.

- ^ World Professional Association for Transgender Health. WPATH Clarification on Medical Necessity of Treatment, Sex Reassignment, and Insurance Coverage in the U.S.A. Archived 30 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (2008).

- ^ World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Version 7. Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine pg. 58 (2011).

- ^ a b c Fee, Elizabeth (Fall 1979). "Nineteenth-Century Craniology: The Study of the Female Skull". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 53 (3): 415–33. PMID 394780.

- ^ "5d. The Interior of the Skull". Gray's Anatomy. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Other Sources:

- Li, Haiyan; Ruan, Jesse; Xie, Zhonghua; Wang, Hao; Liu, Wengling (2007). "Investigation of the critical geometric characteristics of living human skulls utilising medical image analysis techniques". International Journal of Vehicle Safety. 2 (4): 345. doi:10.1504/IJVS.2007.016747.

- name="Men May Be More Susceptible To Head Injury Than Women, Study Suggests">"Men May Be More Susceptible To Head Injury Than Women, Study Suggests". ScienceDaily. 22 January 2008. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- De Boer, H. H. (Hans); Van der Merwe, A. E. (Lida); Soerdjbalie-Maikoe, V. (Vidija) (September 2016). "Human cranial vault thickness in a contemporary sample of 1097 autopsy cases: relation to body weight, stature, age, sex and ancestry". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 130 (5): 1371–1377. doi:10.1007/s00414-016-1324-5. ISSN 0937-9827. PMC 4976057. PMID 26914798.

- Ross, M. D.; Lee, K. A.; Castle, W. M. (10 April 1976). "Skull thickness of Black and White races". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 50 (16): 635–638. ISSN 0256-9574. PMID 1224277.

- Adeloye, Adelola; Kattan, Kenneth R.; Silverman, Frederic N. (July 1975). "Thickness of the normal skull in the American blacks and whites". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 43 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330430105. PMID 1155589.

- "International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences". www.msjonline.org. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- Ekşi, Murat Şakir; Güdük, Mustafa; Usseli, Murat Imre (19 November 2020). "Frontal Bone is Thicker in Women and Frontal Sinus is Larger in Men: A Morphometric Analysis". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 32 (5): 1683–1684. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000007256. ISSN 1536-3732. PMID 33229988. S2CID 227159148.

- ^ Lynnerup, Niels; Astrup, Jacob G.; Sejrsen, Birgitte (2005). "Thickness of the human cranial diploe in relation to age, sex and general body build". Head & Face Medicine. 1 13. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-1-13. PMC 1351187. PMID 16364185.

- ^ McKeever, Catherine K.; Schatz, Philip (2003). "Current Issues in the Identification, Assessment, and Management of Concussions in Sports-Related Injuries". Applied Neuropsychology. 10 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1207/S15324826AN1001_2. PMID 12734070. S2CID 33825332.

- ^ Lillie, Elizabeth M.; Urban, Jillian E.; Lynch, Sarah K.; Weaver, Ashley A.; Stitzel, Joel D. (2016). "Evaluation of Skull Cortical Thickness Changes With Age and Sex From Computed Tomography Scans". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 31 (2): 299–307. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2613. ISSN 1523-4681. PMID 26255873.

- ^ Schulte-Geers, Christina; Obert, Martin; Schilling, René L.; Harth, Sebastian; Traupe, Horst; Gizewski, Elke R.; Verhoff, Marcel A. (2011). "Age and gender-dependent bone density changes of the human skull disclosed by high-resolution flat-panel computed tomography". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 125 (3): 417–425. doi:10.1007/s00414-010-0544-3. PMID 21234583. S2CID 39294670.

- ^ G., V.; Gowri s.r., M.; J., A. (2013). "Sex Determination of Human Mandible Using Metrical Parameters". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 7 (12): 2671–2673. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/7621.3728. PMC 3919368. PMID 24551607.

- ^ Capasso, Luigi (2002). Principi di storia della patologia umana: corso di storia della medicina per gli studenti della Facoltà di medicina e chirurgia e della Facoltà di scienze infermieristiche (in Italian). Rome: SEU. ISBN 978-88-87753-65-3. OCLC 50485765.

- ^ Restak, Richard (2000). "Fixing the Brain". Mysteries of the Mind. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-0-7922-7941-9. OCLC 43662032.

External links

[edit]- Skull Module (California State University Department of Anthology)

- Skull Anatomy Tutorial. (GateWay Community College)

- Bird Skull Collection Bird skull database with very large collection of skulls (Agricultural University of Wageningen)

- Human skull base (in German)

- Human Skulls / Anthropological Skulls / Comparison of Skulls of Vertebrates (PDF; 502 kB)

Skull

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Human Skull

The human skull comprises 22 bones in adults, with 21 forming immovable joints and the mandible being mobile.[1] These bones unite via fibrous sutures to create a rigid structure that protects the brain and supports facial features.[3] The skull divides into the neurocranium, which encases the brain, and the viscerocranium, which forms the facial skeleton.[5] The neurocranium includes eight bones: the frontal bone anteriorly, two parietal bones superiorly, the occipital bone posteriorly, two temporal bones laterally, the sphenoid bone at the base anteriorly, and the ethmoid bone centrally.[1] These form the cranial vault (calvaria) and cranial base, providing structural support and attachment for muscles while housing the brain, meninges, and cerebral vasculature.[6] The cranial base features foramina such as the foramen magnum for the spinal cord and jugular foramina for venous drainage and cranial nerves.[1] The viscerocranium consists of 14 bones: two maxillae, two zygomatic bones, the mandible, two nasal bones, two lacrimal bones, two palatine bones, two inferior nasal conchae, and the vomer.[1] These support the orbits, nasal cavity, and oral cavity, anchoring teeth and facilitating mastication and sensory functions.[7] The mandible, the largest facial bone, articulates with the temporal bones at the temporomandibular joints, enabling jaw movement.[6] In infants, the skull includes fontanelles—membranous gaps at suture intersections—that allow brain growth and molding during birth; the anterior fontanelle closes by 18-24 months, while posterior closes by 2-3 months.[8] Adult sutures, such as coronal, sagittal, and lambdoid, remain fibrous but fuse progressively with age, typically beginning in the third decade.[9] This ossification enhances structural integrity but reduces flexibility.[8]Vertebrate Skull Comparisons

In vertebrates, the skull comprises three primary components: the neurocranium (or chondrocranium), which forms the braincase from cartilage that may ossify; the dermatocranium, consisting of membrane bones overlaying the braincase; and the splanchnocranium, derived from branchial arches for jaw and gill support.[10] These elements vary across classes to accommodate aquatic versus terrestrial locomotion, feeding mechanics, and sensory demands.[11] Fishes exhibit the most primitive skull configurations, with chondrichthyans (e.g., sharks) retaining a fully cartilaginous structure for flexibility in predatory strikes, lacking extensive ossification to reduce weight in buoyant environments.[12] Osteichthyans (bony fishes) develop dermal and endochondral bones, including opercular series for gill cover and branchiostegal rays for respiration, enabling precise jaw suspension via quadrate-articular joints.[12] This contrasts with tetrapods, where gill arches reduce to form jaws and middle ear elements, eliminating opercular bones.[11] Amphibian skulls are lighter and less ossified than those of fishes, with extensive loss of dermal roofing bones (e.g., reduced intertemporal) and a kinetic quadrate allowing loose jaw articulation for swallowing large prey, adaptations tied to moist terrestrial habitats and larval aquatic stages.[11] In lissamphibians, the braincase remains partially cartilaginous, and palatal bones are simplified, differing from the robust, fully bony skulls of amniotes that support dry environments.[11] Amniote skulls diversify via temporal fenestrae—lateral openings for jaw adductor muscle expansion. Anapsids (e.g., turtles) retain a solid skull roof without fenestrae, prioritizing protective enclosure over muscle leverage.[13] Synapsids, ancestral to mammals, feature one infratemporal fenestra, evolving into a mammalian configuration with a dentary-dominant jaw, secondary palate for simultaneous breathing and chewing, and enlarged braincase housing expanded cerebral hemispheres.[14][15] Diapsids (reptiles and birds) have two fenestrae (supra- and infratemporal), enhancing bite force; reptiles often fuse the postorbital and squamosal bars for rigidity, while crocodilians retain partial kinesis.[14][13] Bird skulls, derived from diapsid ancestors, are highly lightweight with pneumatized bones forming air-filled sinuses (up to 30% volume reduction compared to reptiles) and extensive cranial kinesis via flexible synovial joints between the premaxilla, maxilla, and braincase, facilitating beak manipulation for seed cracking or probing without robust musculature.[16][17] This contrasts with mammalian skulls' rigid immobilization for precise occlusion of complex teeth, where birds replace dentition with a keratinous rhamphotheca and lose the lower temporal bar entirely.[17][15]| Vertebrate Class | Temporal Fenestrae | Key Skull Features |

|---|---|---|

| Fishes (Chondrichthyes) | None | Fully cartilaginous; hyostylic jaw suspension for flexibility.[12] |

| Amphibians | None (variable kinesis) | Reduced dermal bones; streptostylic quadrate for gape.[11] |

| Reptiles (Diapsids) | Two | Fused bars for strength; ectopterygoid present.[13] |

| Birds (Diapsids) | Modified (one fused) | Kinetic, pneumatized; loss of teeth, quadrate.[17] |

| Mammals (Synapsids) | One (evolved) | Secondary palate; dentary jaw; two occipital condyles.[15] |