Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

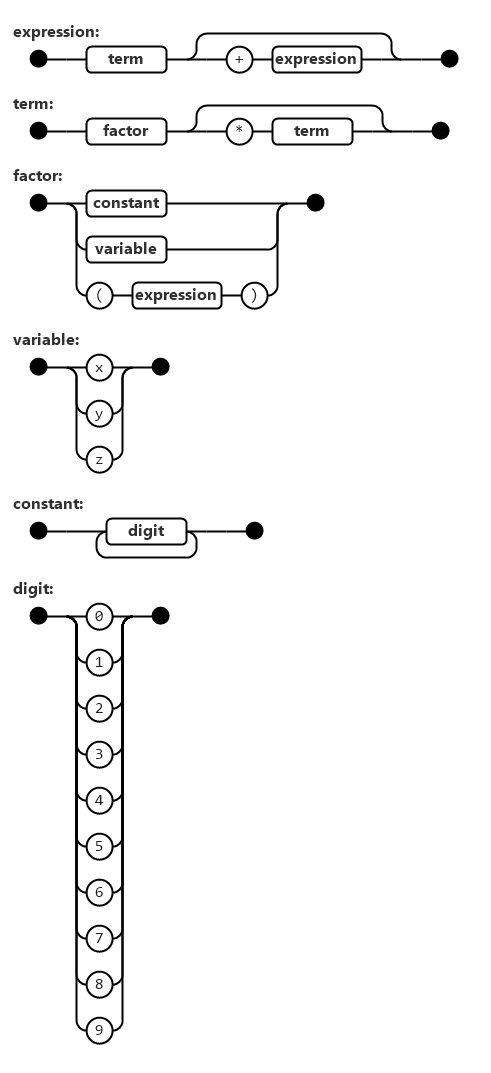

Syntax diagram

View on WikipediaSyntax diagrams (or railroad diagrams) are a way to represent a context-free grammar. They represent a graphical alternative to Backus–Naur form, EBNF, Augmented Backus–Naur form, and other text-based grammars as metalanguages. Early books using syntax diagrams include the "Pascal User Manual" written by Niklaus Wirth[1] (diagrams start at page 47) and the Burroughs CANDE Manual.[2] In the compilation field, textual representations like BNF or its variants are usually preferred. BNF is text-based, and used by compiler writers and parser generators. Railroad diagrams are visual, and may be more readily understood by laypeople, sometimes incorporated into graphic design. The canonical source defining the JSON data interchange format provides yet another example of a popular modern usage of these diagrams.

Principle

[edit]The representation of a grammar is a set of syntax diagrams. Each diagram defines a "nonterminal" stage in a process. There is a main diagram which defines the language in the following way: to belong to the language, a word must describe a path in the main diagram.

Each diagram has an entry point and an end point. The diagram describes possible paths between these two points by going through other nonterminals and terminals. Historically, terminals have been represented by round boxes and nonterminals by rectangular boxes but there is no official standard.

Example

[edit]We use arithmetic expressions as an example, in various grammar formats.

BNF:

<expression> ::= <term> | <term> "+" <expression>

<term> ::= <factor> | <factor> "*" <term>

<factor> ::= <constant> | <variable> | "(" <expression> ")"

<variable> ::= "x" | "y" | "z"

<constant> ::= <digit> | <digit> <constant>

<digit> ::= "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9"

EBNF:

expression = term , [ "+" , expression ];

term = factor , [ "*" , term ];

factor = constant | variable | "(" , expression , ")";

variable = "x" | "y" | "z";

constant = digit , { constant };

digit = "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9";

ABNF:

expression = term ["+" expression]

term = factor ["*" term]

factor = constant / variable / "(" expression ")"

variable = "x" / "y" / "z"

constant = 1*digit

DIGIT = "0" / "1" / "2" / "3" / "4" / "5" / "6" / "7" / "8" / "9"

ABNF also supports ranges, e.g. DIGIT = %x30-39, but it is not used here for consistency with the other examples.

Red (programming language) Parse Dialect:

Red [Title: "Parse Dialect"]

expression: [term opt ["+" expression]]

term: [factor opt ["*" term]]

factor: [constant | variable | "(" expression ")"]

variable: ["x" | "y" | "z"]

constant: [some digit]

digit: ["0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9"]

This format also supports ranges, e.g. digit: charset [#"0" - #"9"], but it is not used here for consistency with the other examples.

One possible syntax diagram for the example grammars is below. While the syntax for the text-based grammars differs, the syntax diagram for all of them can be the same because it is a metalanguage.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Note: the first link is sometimes blocked by the server outside of its domain, but it is available on archive.org. The file was also mirrored at standardpascal.org.

External links

[edit]- JSON website including syntax diagrams

- Generator from EBNF

- From EBNF to a postscript file with the diagrams

- EBNF Parser & Renderer

- SQLite syntax diagram generator for SQL

- Online Railroad Diagram Generator

- Augmented Syntax Diagram (ASD) grammars

- (ASD) Augmented Syntax Diagram Application Demo Site

- SRFB Syntax Diagram representation by Function Basis + svg generation

Syntax diagram

View on GrokipediaSELECT in SQL), ovals or italics for user-supplied variables (e.g., a table name), circles for punctuation like commas or parentheses, branching paths or vertical stacks for mutually exclusive choices, and loops for repeatable sequences.[4][1] This structure allows users to trace valid "paths" through the diagram, akin to following railroad tracks, to construct correct syntax without parsing dense rules.[1]

Originating as a tool for formal language specification, syntax diagrams were popularized by Niklaus Wirth in his 1973 Pascal report and user manual, where they illustrated the language's context-free grammar in a more accessible format than BNF.[3][5] Although earlier uses existed, Wirth's application marked their widespread adoption in technical manuals for languages like SQL, PL/I, and command-line interfaces.[6] Today, they remain a standard in software documentation from vendors like IBM, Oracle, and in standards such as DITA for technical content, valued for their clarity in conveying nested and optional syntax rules.[1][4][2]

Fundamentals

Definition

A syntax diagram, also known as a railroad diagram, is a graphical representation of a context-free grammar, formalizing the syntax of a language as a set of mutually recursive binary relations over nodes that depict possible derivations.[5] In this formalism, paths through the diagram—from an entry point to an exit point—correspond to valid strings generated by the grammar, where each path traces a sequence of syntactic expansions.[7] Context-free grammars provide the underlying basis, consisting of terminals, nonterminals, production rules, and a start symbol.[5] Key terminology in syntax diagrams includes terminals, which are literal symbols from the alphabet of the language, and nonterminals, which are variables denoting syntactic substructures that can be further expanded via production rules.[8] Terminals are typically visualized as fixed elements along the paths, while nonterminals serve as modular points of recursion or branching.[5] Every diagram includes a single entry point, marking the start of a syntactic construct, and an exit point, signifying its completion, with all valid paths connecting these endpoints.[7] In contrast to linear notations like Backus-Naur Form (BNF), which express rules textually, syntax diagrams utilize arrows to indicate directional flow and boxes to enclose elements, thereby illustrating syntactic rules through a visual, flowchart-like structure that aids in tracing alternatives and sequences.[9] This graphical approach renders the hierarchical and recursive nature of grammars more intuitively navigable.[8] Syntax diagrams lack an official standardization, leading to common conventions—such as rectangles for nonterminals and circles for terminals—that vary across implementations and documentation styles.[9] These variations arise from their ad hoc adoption in language specifications, without a governing body enforcing uniformity.[5]Purpose and Advantages

Syntax diagrams, also known as railroad diagrams, serve as a graphical method to specify the syntax of formal languages, such as programming languages and communication protocols, by depicting the structure of production rules and enabling the visualization of recursion and alternatives in a flowchart-like format.[10] This approach illustrates how symbols—terminals and nonterminals—combine to form valid constructs, allowing users to follow paths that represent possible derivations in the grammar. Unlike purely textual notations, syntax diagrams emphasize the hierarchical and sequential relationships inherent in context-free grammars, making them particularly effective for defining the allowable forms of expressions or commands.[11] One key advantage of syntax diagrams is their enhanced intuitiveness for human readers compared to linear textual grammars like Backus-Naur Form (BNF), as they leverage visual cues such as branching paths and loops to convey optional elements, repetitions, and choices without requiring mental parsing of recursive rules. This facilitates easier tracing of valid derivations, where users can intuitively navigate the diagram to understand permissible sequences, reducing cognitive load and improving comprehension of complex nesting structures that would otherwise appear dense in prose. For instance, in documentation for standards like JSON or SQL, these diagrams support quick identification of syntax variations, aiding developers and protocol designers in verifying compliance without exhaustive rule enumeration. In educational and reference contexts, syntax diagrams excel at helping learners grasp grammar rules by providing a spatial representation that mirrors the decision-making process in parsing, thereby accelerating the learning curve for syntax specification without the need to interpret abstract metasyntax. Their pedagogical value lies in transforming abstract formalisms into tangible visuals, which is especially beneficial for visual learners encountering recursive definitions. However, they can introduce complexity in highly recursive structures, where extensive loops may obscure overall flow if not laid out carefully.Graphical Elements

Components

Syntax diagrams are constructed from a set of core graphical elements that visually encode the structure of a formal grammar, typically a context-free grammar. The entry point, often depicted as a starting arrow or double right-pointing arrows (►►), indicates the beginning of a valid parse path, from which the diagram's flow originates.[12] Similarly, the exit point, shown as facing arrows (►◄) or a terminating line, marks the end of the path, signifying a complete and valid derivation.[13] These points ensure that diagrams are traversed directionally, usually from left to right or top to bottom, to represent sequential progression in syntax rules.[14] Straight paths, rendered as horizontal lines or sequences of connected elements, illustrate mandatory sequences of syntactic constructs, where each segment must be followed in order to form a valid string. Branches, appearing as diverging lines or vertical stacks, denote alternatives, allowing selection of one path among multiple options to express choices in the grammar, such as optional keywords or mutually exclusive parameters. Loops, constructed via curved return lines or repeated segments, capture repetition, enabling zero or more iterations of a substructure, often with separators like commas for lists. Arrows along these paths enforce directionality, guiding the reader through the flow and preventing ambiguous interpretations.[14][13] The primary shapes distinguish between terminal and nonterminal symbols. Terminals, which are literal tokens or keywords that appear directly in the language (e.g., "if" or punctuation), are typically enclosed in rounded boxes, ovals, or circles to emphasize their fixed nature. Nonterminals, representing syntactic categories that expand into other rules (e.g., "expression" or "statement"), are usually placed in rectangular boxes, indicating their derivable content. These shapes facilitate quick identification: terminals are consumed as-is, while nonterminals invoke sub-diagrams.[15] Recursion is handled through self-referential elements, such as self-loops where a path returns to a nonterminal within the same diagram, or nested sub-diagrams that reference external rules, allowing infinite derivations bounded by the grammar's context-free constraints. In path interpretation, a string is valid if it corresponds to a complete, connected path from the entry to the exit point, where terminals are matched literally and nonterminals are recursively expanded according to their definitions, ensuring adherence to the underlying grammar.[14]Conventions and Variations

Syntax diagrams adhere to several standard conventions to ensure clarity in representing grammatical structures. The primary flow is read from left to right, following the direction of arrows along the main path, which typically begins with a double right arrow (>>) and ends with a right-and-left arrow pair (><).[16][17] Sequences of required elements are depicted in a horizontal layout on this main path, promoting a linear reading experience akin to natural language progression.[18] Choices or alternatives are illustrated through vertical branches or stacks, where mutually exclusive options are aligned perpendicular to the main path, allowing readers to select one route.[17][16] Optional elements exhibit some divergence in presentation across implementations. In many systems, they are positioned below the main path as recessed branches, enabling a bypass without altering the core flow.[16] Others place optional components above the main path in vertical stacks, emphasizing their non-mandatory nature through elevation.[17] Repetition is commonly shown with looping arrows that return to the preceding element, sometimes including delimiters like commas for multiple instances.[18] Variations in stylistic elements further adapt syntax diagrams to specific contexts or tools. Shapes distinguish element types: terminals (e.g., keywords) often appear in uppercase within rectangles, while nonterminals (e.g., variables) use lowercase in ovals.[17] Arrows are predominantly straight lines with right-angle turns for branches, but some generators employ curved arrows for smoother visual flow in loops or complex junctions.[14] Colors may be introduced for differentiation, such as blue shading for nonterminals or customizable palettes to highlight categories, though monochrome remains prevalent in formal documentation.[19] Textual labels are typically embedded directly inside these shapes, ensuring immediate association without external legends.[20] To manage complexity in larger grammars, syntax diagrams incorporate modularity through sub-diagrams, where detailed expansions of nonterminals are referenced separately and linked by name or index.[17] This referencing often uses numbered or labeled callouts (e.g., "see diagram 3") to avoid monolithic visuals, with wrapping algorithms aligning branches to fit page widths while preserving semantic hierarchy.[14] The absence of a universal standard leads to inconsistencies across tools and manuals, such as differing positions for optionals or arrow curvatures, potentially confusing readers unfamiliar with a particular style.[16][17] Nevertheless, the core logic of path traversal—horizontal sequences, vertical choices, and modular references—remains consistent, maintaining the diagrams' utility for grammar comprehension.[14]History and Development

Origins

Syntax diagrams emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s as visual tools to represent the syntax of programming languages and command interfaces, offering a graphical alternative to textual notations such as Backus-Naur Form (BNF). This development was motivated by the need to make grammar specifications more accessible and easier to comprehend in technical documentation, where BNF's linear, recursive structure could be difficult for non-specialists to follow without repeated reference.[21] Preceding influences include the Burroughs CANDE (Command AND Edit) manual for the B6700/B7700 systems, published in October 1972, which utilized similar graphical syntax aids to depict command structures and data processing language rules. These early diagrams drew from conceptual roots in flowchart techniques of the 1950s and 1960s, which had been employed in systems design to visually map algorithms and processes, adapting such methods to illustrate grammatical productions.[22][23] The earliest widely recognized use of syntax diagrams in programming language documentation appears in Niklaus Wirth's The Programming Language Pascal (Revised Report) (July 1973), where they are introduced starting on page 47 to specify Pascal's syntax rules. This application highlighted their utility in clarifying context-free grammars for practical language implementation and user education. They were later included in the Pascal User Manual and Report by Kathleen Jensen and Niklaus Wirth (first edition, 1974).[24]Evolution and Standardization Efforts

Following the foundational work of Niklaus Wirth in the late 1960s, syntax diagrams experienced significant growth in adoption during the post-1970s period, particularly in technical documentation for programming languages and data formats. This expansion was driven by their utility in clarifying complex grammars beyond textual notations like Backus-Naur Form (BNF). In database systems, syntax diagrams became a standard feature in SQL manuals from major vendors starting in the 1980s and continuing through the 2010s. For instance, IBM's DB2 documentation has employed syntax diagrams to illustrate query structures, guiding users through required and optional elements via linear paths.[25] Similarly, Microsoft's Transact-SQL reference materials use these diagrams to depict statement conventions, such as precedence and repetition, enhancing accessibility for developers.[26] The standardization of JSON by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in the 2010s further propelled their use. RFC 7159, published in 2014, defined JSON as a lightweight data interchange format using textual syntax, but complementary visual aids emerged to support it.[27] The JSON.org website adopted railroad diagrams— a variant of syntax diagrams—to graphically represent the JSON grammar, including elements like objects, arrays, and strings, making the specification more intuitive for web developers.[28] This integration aligned with the era's web technologies, where Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) enabled dynamic, browser-renderable diagrams, facilitating their embedding in online standards and tutorials.[29] Key milestones in the 2000s and 2010s highlighted practical institutionalization. Red Hat Incorporated incorporated syntax diagrams into its enterprise Linux documentation during this period, using them to describe command-line syntax in guides like the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 reference, where paths denote mandatory and optional components.[30] A pivotal advancement came with automated generation tools; in 2013, Tab Atkins released an open-source JavaScript library for creating SVG-based railroad diagrams from EBNF grammars, directly influencing the JSON.org visuals and enabling broader programmatic use in web contexts.[31] This tool, along with variants like Gunther Rademacher's generator, marked a shift toward scalable production of diagrams for language specifications.[20] Efforts toward standardization have remained informal, with no dedicated International Organization for Standardization (ISO) specification governing syntax diagram notation or generation. Instead, de facto conventions have arisen from influential implementations, such as the clean, linear styling on JSON.org, which prioritizes horizontal flow for terminals and non-terminals, and has been replicated in tools like Atkins' library.[32] These practices draw from shared conventions in parsing communities, where diagrams serve as visual supplements to formal grammars. In parsing literature, occasional proposals advocate for graphical enhancements to BNF for educational and implementation purposes, emphasizing consistent path-based representations to aid compiler design and grammar validation, though without leading to unified standards.[21] In the 2020s, syntax diagrams continue to see interest, particularly with advancements in automated layout tools for grammar visualization. For example, a 2024 paper proposes formal methods for automatic generation of railroad diagrams to improve scalability in documenting complex grammars.[33] This ongoing development underscores their enduring role in making formal languages accessible in modern software ecosystems.Examples and Applications

Basic Examples

Syntax diagrams provide a visual means to illustrate the structure of simple grammars, making it easier to understand how valid strings are formed by following defined paths. These basic examples focus on fundamental constructs like repetition through loops and linear sequences, demonstrating core principles without complexity.Example 1: Simple Expression Grammar

A common introductory grammar for arithmetic expressions allows a term followed optionally by multiple additions of further terms. The Backus-Naur Form (BNF) representation is:<expr> ::= <term> | <expr> + <term>

<expr> ::= <term> | <expr> + <term>

<expr> is the nonterminal for an expression, <term> represents a basic operand (such as an identifier or number), and + is a literal terminal symbol.[10]

In the corresponding syntax diagram (also known as a railroad diagram), the path starts at the left with a double right arrow leading to a rectangular box labeled <term>. From there, the main line continues straight to the right end, marked by a right-left arrow pair, representing the base case of a single term. To depict the recursive addition, a looped branch diverges from the point after <term>: it follows a track labeled with the terminal + (often in an oval or circle), then connects to another <term> box, and arrows back to the junction point after the initial <term>, allowing zero or more repetitions of + <term>. This loop visually encodes the left-recursive rule, enabling paths that traverse the loop multiple times.[34][15]

To interpret the diagram, one traces allowable paths from start to end. For instance, a direct path through <term> (substituting "a" for <term>) generates the string "a". Traversing the loop once yields <term> + <term>, such as "a + b". A second loop iteration produces "a + b + c", illustrating how the diagram generates expressions with additive chains while maintaining left-associativity through the recursive structure.[10]

Example 2: Sequence Rule for a Statement

Another basic construct is a linear sequence, such as a simple variable declaration statement requiring a keyword followed by an identifier. The BNF equivalent is:<stmt> ::= let <id>

<stmt> ::= let <id>

let is a required terminal keyword, and <id> is a nonterminal for an identifier (e.g., a sequence of letters).[10]

The syntax diagram for this rule features a straightforward linear path: it begins with the double right arrow connecting directly to an oval or circle containing the literal terminal "let", followed immediately by a rectangular box labeled <id>, and terminates at the right with the right-left arrow pair. There are no branches or loops, emphasizing the mandatory sequential order without options or repetitions. Nonterminals like <id> may link to their own sub-diagrams, but in this isolated example, it serves as an endpoint placeholder.[34][15]

Following the single available path generates valid declaration strings. Substituting "x" for <id> produces "let x", a complete statement. This linear flow highlights how syntax diagrams enforce strict ordering for syntactic elements like keywords preceding variables.[10]

Real-World Applications

Syntax diagrams find extensive application in programming language documentation, where they visually depict the structure of language clauses to facilitate comprehension for both users and implementers. For instance, the Free Pascal reference guide employs syntax diagrams to illustrate the grammar of statements, expressions, and declarations, enabling developers to trace valid constructions from left to right along the diagram paths.[35] Similarly, Oracle Database SQL manuals utilize syntax diagrams to represent query clause structures, such as those in SQL*Loader commands, highlighting optional and required elements through branching paths and loops.[36] In data format specifications, syntax diagrams provide a graphical overview of structural rules, particularly for nested constructs. The official JSON.org site presents railroad diagrams for JSON syntax, detailing how objects—enclosed in curly braces with comma-separated key-value pairs—and arrays—enclosed in square brackets with ordered values—are formed, as aligned with the ECMA-404 standard's second edition released in December 2017.[28][37] These diagrams clarify rules like string quoting, number formats, and nesting, aiding precise data interchange across systems. For protocols and APIs, syntax diagrams assist in elucidating request and response parsing logic. The GraphQL specification's grammar, while primarily textual, has been visualized using railroad diagrams in community-derived documentation, such as EBNF-based generators that map query structures, fragments, and directives for accurate client-server interactions.[38] In practice, these applications yield tangible benefits, including accelerated developer onboarding through visual syntax clarity that reduces the cognitive load of learning complex grammars.[39] Additionally, syntax diagrams contribute to error reduction in compiler and parser design by allowing implementers to validate grammar rules against visual representations, as seen in Pascal's reference materials targeted at language creators.[40] Standards bodies like the IETF have referenced such evolutions in incorporating visual aids alongside formal notations in protocol specs.Comparisons and Alternatives

Text-Based Notations

Text-based notations for specifying syntax, such as Backus-Naur Form (BNF), Extended BNF (EBNF), and Augmented BNF (ABNF), provide linear, rule-based descriptions of context-free grammars that underlie syntax diagrams.[41][42][43] BNF, introduced in the 1960 ALGOL 60 report, uses production rules defined with::= to assign nonterminals (often enclosed in angle brackets, like <expression>) to sequences of terminals and nonterminals, with | denoting alternatives; for example, <digit> ::= 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.[41][44] Repetition in BNF requires recursive rules, such as defining <digits> ::= <digit> | <digits> <digit>.[44]

EBNF extends BNF for conciseness by incorporating operators like parentheses for grouping, square brackets [] for optional elements, curly braces {} or * for zero or more repetitions, and + for one or more; an example is number = ["-"] digit {digit}, avoiding recursion for repetitions.[42][44] This notation, standardized in ISO/IEC 14977, maintains equivalence to BNF while reducing rule count.[45]

ABNF, defined in RFC 5234 for Internet protocols, further modifies BNF by using = for definitions, / for alternatives, and * for repetitions with ranges (e.g., 1*3DIGIT for 1 to 3 digits), plus hexadecimal literals for character ranges like %x41-5A for uppercase letters.[43] It supports case-insensitive matching and concatenation without explicit symbols, enhancing compactness for protocol specifications.[43]

Syntax diagrams differ from these notations by visually depicting grammar flow as directed graphs with branches for alternatives and loops for recursion, whereas BNF variants require sequential reading of textual rules.[44][21] In diagrams, alternatives appear as forks in "railroad tracks," and recursion as cycles, making structural relationships immediately apparent without parsing recursive definitions.[21] Textual notations, conversely, linearize the grammar, which can obscure nested or optional elements in complex rules.[44]

Syntax diagrams are preferred for visual learners or when illustrating intricate alternatives and repetitions, as their graphical layout aids intuition in educational contexts and documentation of complex languages.[21] Text-based notations like BNF, EBNF, and ABNF excel in compactness, making them suitable for embedding in source code, standards documents, or automated parser generation where brevity and machine readability are prioritized.[43][44]

Automating conversion from BNF to syntax diagrams involves parsing the grammar into a graph representation and applying layout algorithms, such as treating rules as nodes and alternatives/recursions as edges, often requiring traversal techniques like depth-first search to resolve cycles.[46][5] Challenges arise from handling left recursion, ambiguities in textual grouping, and optimizing diagram aesthetics, which demand additional graph algorithms for non-overlapping branch rendering.[5]