Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

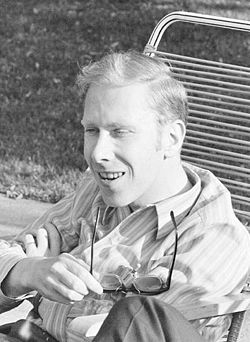

Niklaus Wirth

View on Wikipedia

Niklaus Emil Wirth (IPA: /vɛrt/) (15 February 1934 – 1 January 2024) was a Swiss computer scientist. He designed several programming languages, including Pascal, and pioneered several classic topics in software engineering. In 1984, he won the Turing Award, generally recognized as the highest distinction in computer science, "for developing a sequence of innovative computer languages".[4]

Key Information

Early life and education

[edit]Niklaus Emil Wirth was born in Winterthur, Switzerland, on 15 February 1934.[5] He was the son of Hedwig (née Keller) and Walter Wirth, a high school teacher.[6] Wirth studied electronic engineering at the Federal Institute of Technology, Zürich (ETH Zürich) from 1954 to 1958, graduating with a Bachelor of Science (B.S.) degree.[6] In 1960, he earned a Master of Science (M.Sc.) from Université Laval in Quebec.[6] Then in 1963, he was awarded a PhD in electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) from the University of California, Berkeley, supervised by computer design pioneer Harry Huskey.[7]

Career

[edit]From 1963 to 1967, Wirth served as assistant professor of computer science at Stanford University and again at the University of Zürich.[6] In 1968, he became a professor of informatics at ETH Zürich, taking two one-year sabbaticals at Xerox PARC in California (1976–1977 and 1984–1985). He retired in 1999.[7]

Although Wirth was involved with developing international standards in programming and informatics, as a member of the International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP) Working Group 2.1 on Algorithmic Languages and Calculi,[8] which specified, maintains, and supports the programming languages ALGOL 60 and ALGOL 68,[9] he got frustrated by the discussions in the standards groups and published his languages later on as personal work, mainly Pascal, Modula-2 and Oberon.

In 2004, he was made a Fellow of the Computer History Museum "for seminal work in programming languages and algorithms, including Euler, Algol-W, Pascal, Modula, and Oberon."[10]

Programming languages

[edit]

Wirth was the chief designer of the programming languages Euler (1965), PL360 (1966), ALGOL W (1966), Pascal (1970),[11] Modula (1975), Modula-2 (1978),[7] Oberon (1987), Oberon-2 (1991), and Oberon-07 (2007).[12] He was also a major part of the design and implementation team for the operating systems Medos-2 (1983, for the Lilith workstation),[13] and Oberon (1987, for the Ceres workstation),[14][15] and for the Lola (1995) digital hardware design and simulation system.[16][17]

In 1984, Wirth received the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) Turing Award for the development of these languages.[18] In 1994, he was inducted as a Fellow of the ACM.[19]

In 1999, he received the ACM SIGSOFT Outstanding Research Award[20]

Wirth's law

[edit]In 1995, he popularized the adage now named Wirth's law. In his 1995 paper "A Plea for Lean Software" he attributed the following to Martin Reiser phrasing it as, "Software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster."[21]

Publications

[edit]The April 1971 Communications of the ACM article "Program Development by Stepwise Refinement",[22][23] concerning the teaching of programming, is considered to be a classic text in software engineering.[24] The paper is considered to be the earliest work to formally outline the top-down method for designing programs.[25][26] The article was discussed by Fred Brooks in his influential book The Mythical Man-Month and was described as "seminal" in the ACM's brief biography of Wirth published in connection to his Turing Award.[27][28]

The 1973 textbook, Systematic Programming: An Introduction,[29] was described as a quality source for mathematicians desiring to understand the nature of programming in a 1974 review.[30] The cover flap, of the 1973 edition, stated the book "... is tailored to the needs of people who view a course on systematic construction of algorithms as part of their basic mathematical training, rather than to the immediate needs of those who wish to be able to occasionally encode a problem and hand it over to their computer for instant solution."[31] Described in the review as a challenging text to work through, it was nevertheless recommended as useful reading for those interested in numerical mathematics.[32]

In 1974, The Pascal User Manual and Report,[33] jointly written[i] with Kathleen Jensen,[36] served as the basis of many language implementation efforts in the 1970s (BSD Pascal[37]), and 1980s in the United States and across Europe.[38][39]

In 1975, he wrote the book Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs, which gained wide recognition.[40] Major revisions of this book with the new title Algorithms & Data Structures were published in 1986 and 2004.[41][42] The examples in the first edition were written in Pascal. These were replaced in the later editions with examples written in Modula-2 and Oberon, respectively.[41][42]

In 1992, Wirth and Jürg Gutknecht published the full documentation of the Oberon operating system.[43] A second book, with Martin Reiser, was intended as a programming guide.[44]

Death

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award Recipients" (PDF). IEEE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Niklaus Wirth 2004 Fellow". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Gosch, John (25 October 1979). Weber, Samuel (ed.). "Wirth works to better Pascal" (PDF). Profile. Electronics. Paul W. Reiss. p. 157. ISSN 0013-5070. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

[his family] includes two girls and a boy

- ^ "Niklaus E. Wirth - A.M. Turing Award Laureate". Association for Computing Machinery. 2019. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Henderson, Harry (2009). "Wirth, Niklaus". Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology. Infobase Publishing. p. 514. ISBN 978-1-4381-1003-5.

- ^ a b c d e Zehnder, Carl August: Wirth, Niklaus in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 13 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Pomberger, Gustav; Mössenböck, Hanspeter; Rechenberg, Peter (2000). "Niklaus Wirth - a Pioneer of Computer Science". The School of Niklaus Wirth: The Art of Simplicity. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-932588-85-3.

- ^ Jeuring, Johan; Meertens, Lambert; Guttmann, Walter (17 August 2016). "Profile of IFIP Working Group 2.1". Foswiki. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Swierstra, Doaitse; Gibbons, Jeremy; Meertens, Lambert (2 March 2011). "ScopeEtc: IFIP21: Foswiki". Foswiki. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Niklaus Wirth: 2004 Fellow". Computer History Museum (CHM). Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Petzold, Charles (9 September 1996). "Programming Languages: Survivors and Wannabes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (3 May 2016). The Programming Language Oberon-07 (PDF). ETH Zurich, Department of Computer Science (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Knudsen, Svend Erik (1983). Medos-2: a Modula-2 oriented operating system for the personal computer Lilith (Doctoral Thesis). ETH Zurich. doi:10.3929/ethz-a-000300091. hdl:20.500.11850/137906. Archived from the original on 4 January 2024. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

I am indebted to Prof. N. Wirth for conceiving and coordinating the Lilith project, for giving me the opportunity to design and implement the operating system Medos-2, and for supervising this thesis.

- ^ Franz, Michael (2000). "Oberon: The Overlooked Jewel". In Böszörményi, László (ed.). The School of Niklaus Wirth: The Art of Simplicity. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 42, 45. ISBN 978-3-932588-85-3.

- ^ Proven, Liam (29 March 2022). "The wild world of non-C operating systems". The Register. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (1995). Digital Circuit Design. Springer.

- ^ Eberle, Hans (2000). "Designing a Cluster Network". In Böszörményi, László (ed.). The School of Niklaus Wirth: The Art of Simplicity. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 978-3-932588-85-3.

This class also inspired Niklaus to develop a simple yet powerful hardware description language called Lola. Niklaus has always built the systems he is either researching or teaching himself since he knows that this is the only way to keep an engineer honest and credible.

- ^ Haigh, Thomas (1984). "Niklaus E. Wirth". A. M. Turing Award. Association for Computing Machinery. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ "ACM Fellows by year". acm.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Outstanding Research Award". SIGSOFT. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (February 1995). "A Plea for Lean Software". Computer. 28 (2): 64–68. Bibcode:1995Compr..28b..64W. doi:10.1109/2.348001. S2CID 44803077.

- ^ Wirth, Program development by stepwise refinement, Communications of the ACM,. 14:221–227, ACM Press, 1971

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (2001). "Program Development by Stepwise Refinement". In Broy, Manfred; Denert, Ernst (eds.). Pioneers and Their Contributions to Software Engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-48354-7. ISBN 978-3-642-48355-4. S2CID 11348419.

- ^ Gehani, Narain (1991). Ada: Concurrent Programming. Silicon Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-929306-08-7.

- ^ Gill, Nasib Singh. Software Engineering. Khanna Publishing House. p. 192. ISBN 978-81-906116-3-3.

- ^ Dooley, John F. (25 November 2017). Software Development, Design and Coding: With Patterns, Debugging, Unit Testing, and Refactoring. Apress. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4842-3153-1.

- ^ Brooks, Frederick P. (Frederick Phillips) (1975). The Mythical Man-Month. Reading, Mass. : Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-201-00650-6.

- ^ "Niklaus Wirth: 1984 ACM A. M. Turing Award Recipient". Communications of the ACM. 28 (2). February 1985. doi:10.1145/1283920.1283941.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (8 January 1973). Systematic Programming: An Introduction. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-880369-2.

- ^ Abrahams, Paul; Wirth, Niklaus (July 1974). "Systematic Programming: An Introduction". Mathematics of Computation. 28 (127): 881. doi:10.2307/2005728. JSTOR 2005728.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (1973). "Cover flap". Systematic Programming: An Introduction. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-880369-2.

- ^ Abrahams, Paul (July 1974). "Systematic Programming: An Introduction by Niklaus Wirth". Mathematics of Computation. 28 (127). American Mathematical Society: 881–883. doi:10.2307/2005728. JSTOR 2005728.

- ^ Pascal User Manual and Report Second Edition.

- ^ "Kathleen Jensen's Speech at the Wirth Symposium (20.02.2014)". YouTube. 25 February 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus (1973). The programming language Pascal (Revised Report) (Report). ETH Zurich. pp. 49 p. doi:10.3929/ethz-a-000814158. hdl:20.500.11850/68910.

- ^ * https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/Kathleen-Jensen-2058521472 Archived 6 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- https://dl.acm.org/profile/81334487416 Archived 6 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- https://dblp.org/pid/06/5848.html Archived 6 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joy, William N.; Graham, Susan L.; Haley, Charles B. (1979). Berkeley Pascal User's Manual, Version 1.1, April, 1979. University of California, Berkeley. Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. Archived from the original on 8 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Blotnick, Srully (July 1983). "Don't Fail Me Now" (PDF). Pascal News (26): 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Hartel, Pieter H. (May 1982). "Pascal for systems programmers" (PDF). ECODU-32. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Citations collected by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)

- ^ a b Wirth, Niklaus (1986). "Preface to the 1986 edition". Algorithms & Data Structures. Prentice-Hall. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-13-022005-9.

The major change which pervades the entire text concerns the programming language used to express the algorithms. Pascal has been replaced by Modula-2.

- ^ a b Wirth, Niklaus. "Algorithms and Data Structures" (PDF). ETH Zürich. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

© N. Wirth 1985 (Oberon version: August 2004).

- ^ Wirth, Niklaus; Gutknecht, Jürg (1992). Project Oberon: The Design of an Operating System and Compiler (PDF). Addison-Wesley, ACM Press. ISBN 978-0-201-54428-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2013. Out of print. Online version of a 2nd edition Archived 5 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. 2005 edition, PDF. Archived 8 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Reiser, Martin; Wirth, Niklaus (1992). Programming in Oberon: Steps Beyond Pascal and Modula (PDF). Addison-Wesley, ACM Press. ISBN 978-0-201-56543-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.. Out of print.

- ^ Proven, Liam (4 January 2024). "RIP: Software design pioneer and Pascal creator Niklaus Wirth". The Register. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Wirth, Niklaus (April 1971). "Program Development by Stepwise Refinement". Communications of the ACM. 14 (4): 221–227. doi:10.1145/362575.362577. hdl:20.500.11850/80846. S2CID 13214445.

- Wirth, N. (1974). "On the Design of Programming Languages" (PDF). Proc. IFIP Congress 74: 386–393.

External links

[edit]This February 2024's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (February 2024) |

- Official website, ETH Zürich

- Biography at ETH Zürich

- Niklaus Wirth at DBLP Bibliography Server

- Niklaus E. Wirth at ACM

- Turing Award Lecture, 1984

- Pascal and its Successors paper by Niklaus Wirth – also includes short biography.

- A Few Words with Niklaus Wirth

- The School of Niklaus Wirth: The Art of Simplicity, by László Böszörményi, Jürg Gutknecht, Gustav Pomberger (editors). dpunkt.verlag; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2000. ISBN 3-932588-85-1, ISBN 1-55860-723-4.

- The book Compiler Construction

- The book Algorithms and Data Structures

- The book Project Oberon – The Design of an Operating System and Compiler. The book about the Oberon language and Operating System is now available as a PDF file. The PDF file has an additional appendix Ten Years After: From Objects to Components.

- Project Oberon 2013 Online 2nd Edition of the preceding book adapted for the reimplementation on FPGA hardware.

Niklaus Wirth

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Early Years

Niklaus Emil Wirth was born on February 15, 1934, in Winterthur, Switzerland.[4] He was the only child of Walter Wirth, a geography and geology professor and high school teacher, and Hedwig Wirth, a homemaker.[5][6] Raised in a middle-class Swiss family in a stable, neutral country during the mid-20th century, Wirth experienced an upbringing that emphasized discipline, education, and intellectual curiosity.[7] Wirth's early education took place in local schools in Winterthur, where he attended the Gymnasium for secondary studies.[6] From a young age, he showed a profound enthusiasm for technology and mechanics, tinkering with homemade chemistry experiments in the family basement and disassembling radios to understand their workings.[8] By age 12, he had built his first radio, and his hobbies extended to constructing and flying model airplanes, as well as remote-control helicopters that he often repaired after crashes.[7][4] These activities, pursued in the fields around Winterthur, highlighted his innate technical aptitude and hands-on approach to problem-solving.[8] Switzerland's neutrality during World War II insulated Wirth's childhood from direct conflict, allowing him to focus on self-directed hobbies that fostered resourcefulness and independence in a society known for its orderly, self-reliant ethos.[7] Influenced by his father's academic profession and these early pursuits in electronics and mechanics, Wirth developed initial aspirations toward a career in engineering.[5] This foundation propelled him toward university studies in electrical engineering.[9]Higher Education

Niklaus Wirth began his higher education at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH Zurich), where he studied electrical engineering from 1954 to 1959. He earned a bachelor's degree (Diplom) in electronics engineering in 1959, during which he first encountered computing through the institute's early custom-built machines, such as the ERMETH computer, sparking his interest in programming and hardware design.[10][7] This foundational exposure at ETH, under the influence of pioneering faculty in electrical engineering, laid the groundwork for his shift toward computer science.[3] Following his undergraduate studies, Wirth pursued graduate work in North America. In 1960, he obtained a Master of Science degree in electrical engineering from Université Laval in Quebec, Canada, broadening his technical expertise in a period when computing was rapidly evolving across continents.[10][7] He then moved to the United States for doctoral studies at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1960 to 1963, serving as a research assistant in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences.[11] Wirth completed his PhD in electrical engineering and computer sciences in 1963 at UC Berkeley, supervised by Harry D. Huskey. His dissertation, titled A Generalization of ALGOL, explored extensions to the ALGOL 60 programming language, emphasizing compiler design principles and formal language structures that influenced his later work on structured programming.[11][7] During this time abroad, he also engaged with emerging concepts in time-sharing systems, which were pivotal in the transition from batch processing to interactive computing environments.[3]Career

Early Professional Roles

Following his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 1963, Niklaus Wirth joined Stanford University as an assistant professor of computer science, a position he held from 1963 to 1967.[3] In this role, he contributed to the nascent field by teaching programming courses and engaging in compiler development projects, which exposed him to the practical challenges of implementing efficient software on early mainframe systems like the IBM System/360.[12] These experiences honed his approach to systematic program construction and optimization, emphasizing clarity and portability in code generation.[10] During his time at Stanford, Wirth began shaping foundational ideas on programming language design, focusing on structured constructs and formal definitions to improve readability and reliability without delving into specific implementations.[12] He also became involved in international collaborations, participating in IFIP Working Group 2.1 on ALGOL, where he contributed to discussions on language evolution and methodology following the 1966 Warsaw meeting.[3] This early engagement with global computing forums, including proposals for language extensions, broadened his perspective on standardized practices and cross-platform applicability.[12] In 1967, Wirth transitioned to the University of Zurich as an assistant professor of computer science, serving until 1968.[3] There, he continued his teaching duties in programming and systems design while advancing research on compiler techniques, further refining his principles for modular and verifiable software development amid the growing complexity of computing hardware.[10] This brief stint reinforced his commitment to educational tools that bridged theory and practice, setting the stage for his later academic leadership.[12]Professorship at ETH Zurich

In 1968, Niklaus Wirth joined ETH Zurich as an associate professor of informatics, advancing to full professor the following year and holding the position until his retirement in 1999.[6][13] During this period, he became a cornerstone of the institution's informatics efforts, teaching foundational courses in programming and computing to students across engineering and physics departments while the field was still emerging in Switzerland.[6] Wirth was instrumental in shaping ETH Zurich's informatics curriculum, advocating for a structured approach that prioritized clarity in program design and systematic systems development.[14] Collaborating closely with Carl August Zehnder, he repeatedly proposed the creation of a dedicated computer science study program and department, facing rejections in 1971 and 1975 before its approval in 1980, which marked a significant expansion with initial cohorts growing from 70 to over 200 students by the early 1980s.[6] This curriculum emphasized practical, disciplined methodologies, influencing generations of Swiss computer scientists and establishing ETH as a leader in the discipline.[14] Throughout his career, Wirth mentored dozens of doctoral students—approximately two dozen over nearly four decades—and fostered key collaborations, including with Jürg Gutknecht, who joined his team in the 1980s and later became a professor at ETH, contributing to advancements in systems design.[6][15] Many of his protégés pursued influential careers, particularly in California, extending Wirth's impact beyond Europe.[6] In administrative capacities, Wirth helped lead the evolution of informatics at ETH, including the 1974 upgrade of the Fachgruppe Computerwissenschaften to the Institut für Informatik, where he served in a guiding role amid the department's formative years.[16] His efforts ensured the integration of computing into broader academic structures, supporting research and education amid rapid technological growth.[17] Wirth retired in April 1999, assuming emeritus status while maintaining active engagement in scholarly pursuits at ETH until his death on January 1, 2024.[10][7]Key Projects and Developments

During his professorship at ETH Zurich, Niklaus Wirth led the development of the Lilith workstation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a pioneering personal computer project designed to support the Modula-2 programming language.[18] The first prototype of Lilith was created between 1978 and 1980 by Wirth and his research group, with hardware specialist Richard Ohran contributing to its microprogrammed processor, high-resolution display, and mouse interface.[19] This workstation integrated a fast Modula-2 compiler, an efficient text editor, and a graphical user interface, enabling 20 personal workstations by late 1980 that emphasized simplicity and high-level language support for software development.[20] Wirth also made significant contributions to educational tools and simulators at ETH Zurich, particularly through early compiler toolkits that facilitated teaching and research in programming language implementation. One key example is PL/0, a simplified educational language he introduced in the 1970s to demonstrate compiler construction principles, as detailed in his 1976 book Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs. PL/0 served as the basis for recursive descent parsing examples and was used in ETH courses to build student-implemented compilers, promoting conceptual understanding of syntax analysis and code generation without the complexity of full-scale languages. His work extended to P-code virtual machines and portable compilers, such as the P4 Pascal compiler, which provided simulation environments for cross-platform development and influenced subsequent educational toolkits at the institution.[21] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Wirth co-led Project Oberon with Jürg Gutknecht, creating an integrated hardware-software system for modern workstations that combined a minimalist operating system, compiler, and custom hardware in a single, self-contained environment.[22] Initiated in late 1985 with programming starting in early 1986, the project culminated in the first operational version by fall 1988, featuring the Ceres workstation with an NS32000 processor, 2 MB of memory, tiled window management, and networked services for file sharing and printing.[22] Developed primarily by Wirth and Gutknecht as part-time efforts with support from ETH researchers like Hans Mössenböck, Oberon emphasized modularity, dynamic loading, and object-oriented principles to achieve a compact system that could be fully understood and extended by a small team.[22] Wirth collaborated on early time-sharing and operating systems during his time at Stanford University and later at ETH Zurich, advancing interactive computing paradigms. At Stanford from 1963 to 1967, he contributed to the institution's first time-sharing system on the DEC PDP-1, which restored direct interactivity to programming and influenced subsequent designs like the IBM 360/67.[23] Upon returning to ETH, Wirth directed the development of the Venus time-sharing system in 1970 in cooperation with the ETH computing center, addressing the growing demands of academic users with efficient resource sharing on Burroughs B5500 hardware.[21] Following his retirement in 1999, Wirth released an updated, open-source version of the Oberon system in 2013, adapting it for contemporary FPGA platforms to preserve and extend its legacy as an educational and experimental framework.[24] This edition, co-developed with Paul Reed, included complete source code for the operating system, compiler, and hardware description, enabling reproduction on modern devices like the Digilent Spartan-3 Starter Kit and fostering ongoing community implementations.[24]Programming Languages

Initial Contributions (PL/360 and Euler)

In 1966, while at Stanford University, Niklaus Wirth designed PL/360 as a systems programming language specifically tailored for the IBM System/360 mainframe computers.[25] This language aimed to bridge the gap between low-level assembly coding and higher-level structured programming by providing assembly-like control structures—such as direct manipulation of registers and memory—while imposing a recursive syntax to enhance readability and organization for programs that must account for hardware-specific constraints.[25] Motivated by the limitations of Fortran, which lacked sufficient efficiency and control for systems-level tasks, and Algol 60, which was ill-suited for machine-oriented programming due to its abstract nature, PL/360 sought to support both practical implementation of compilers and educational efforts in algorithmic development.[25][6] The implementation of PL/360 featured a self-hosting compiler written in PL/360 itself, demonstrating its viability for bootstrapping on the System/360 architecture and emphasizing efficiency through one-to-one correspondence with machine instructions without sacrificing structural clarity.[25] This approach allowed Wirth to compile the language's own compiler as a practical exercise, highlighting its utility in teaching compiler construction and low-level systems programming.[6] Building on this experience, Wirth, in collaboration with Helmut Weber, developed Euler between 1966 and 1968 as an extensible programming language intended for mathematical and algorithmic expression, implemented on the Burroughs B5500 computer.[26] Euler extended and generalized concepts from Algol 60, addressing its imprecise semantics and static typing limitations, while critiquing Fortran's rigidity in handling dynamic structures; it introduced features like dynamic type handling, list processing, and procedures as first-class constants to enable user-defined extensions and more flexible algorithmic notation.[26] Influenced by John McCarthy's Lisp, particularly in its support for functional expressions and list manipulation, Euler allowed for the definition of new language constructs at runtime, making it suitable for both teaching advanced programming paradigms and experimenting with formal language definitions.[26][27] Euler's implementation included a self-hosting compiler, initially bootstrapped using Extended Algol on the B5500, which underscored its emphasis on rigorous, unambiguous semantics through a formal definition method that separated syntax from execution rules.[26] This work laid foundational contributions to early structured programming by promoting block structures, procedural abstraction, and precise semantics, influencing subsequent language designs that prioritized clarity and modularity over ad-hoc machine dependencies.[3]Pascal

Pascal was designed by Niklaus Wirth at ETH Zurich between 1968 and 1969 and first released in 1970 as a direct successor to Algol 60, with the primary goal of serving as an effective teaching tool for structured programming concepts.[28][29] The language emphasized clarity, simplicity, and systematic discipline in program construction, building on Algol's block structure while introducing enhancements for data organization and control flow to make it more suitable for educational environments.[30] Wirth's design philosophy prioritized what the language disallowed as much as what it permitted, aiming to prevent common programming errors and promote reliable code.[29] Key features of Pascal included strong static typing to enforce type safety at compile time, reducing runtime errors, alongside support for block structures that encapsulated declarations and statements for better modularity.[31] It provided structured data types such as records for grouping related fields, pointers for dynamic memory allocation, arrays, sets, and files, enabling efficient representation of complex data.[29] Control flow was handled through disciplined constructs like conditional if-then-else statements, while loops, and for loops, with the goto statement retained only as a compromise to anticipated user resistance, though its use was discouraged in favor of structured alternatives to improve readability and maintainability.[31][29] The original implementation involved a compiler for the CDC 6000 series mainframe, completed in 1970 and written partly in Pascal itself after an initial bootstrapping via the Scallop translator.[32] Subsequent ports expanded its reach, including a version for the PDP-11 minicomputer developed at the University of Illinois, which generated native machine code.[33] The UCSD p-System, originating at the University of California, San Diego, further enhanced portability by compiling to intermediate p-code executable on a virtual machine, allowing deployment on diverse hardware like the PDP-11 without major recompilation.[34] Pascal achieved widespread adoption in educational settings, becoming a staple for introductory programming courses at universities including ETH Zurich, where it introduced generations of students to systematic coding practices.[30] Its accessibility was boosted by implementations like the UCSD p-System on the Apple II, which integrated Pascal into school curricula and personal computing from the late 1970s, fostering early exposure to structured programming on affordable hardware.[35] This educational success influenced commercial extensions, such as Borland's Turbo Pascal and later dialects including Object Pascal in Delphi for rapid application development, as well as the open-source Free Pascal compiler, which maintains compatibility while adding modern features.[29] Despite its strengths, Pascal faced criticism for lacking built-in support for separate compilation, requiring entire programs to be recompiled as a single unit, which hindered scalability for large projects and library integration across implementations.[36] This limitation, rooted in the language's one-pass compiler design for efficiency on limited hardware, was addressed in Wirth's later works through modular enhancements.[36]Modula and Successors

In 1975, Niklaus Wirth developed the Modula programming language at ETH Zurich as an extension of Pascal, primarily aimed at supporting modular multiprogramming for dedicated computer systems.[37] Modula introduced the concept of modules to enable separate compilation, allowing programmers to define interfaces and implementations independently while encapsulating abstract data types to promote reusability and maintainability in larger programs.[37] This design addressed the growing need for structured approaches in systems programming, where Pascal's single-file structure proved limiting for complex, multi-programmer projects.[38] Building on Modula, Wirth released Modula-2 in 1978, refining it specifically for systems programming tasks.[39] The language incorporated coroutines for concurrent programming and provided low-level access to hardware through facilities like absolute addressing, while retaining strong typing and modularity from its predecessor.[39] Influenced by the Mesa language encountered during Wirth's 1976 sabbatical at Xerox PARC, Modula-2 emphasized overcoming Pascal's shortcomings in scalability for large-scale software development, such as inadequate support for separate compilation and process synchronization.[38][40] Modula-2 was first implemented on the Lilith personal workstation developed at ETH Zurich, with subsequent compilers ported to various platforms including mainframes, minicomputers, and personal computers.[38] Its structured modularity and efficiency made it suitable for embedded systems, where it was adopted for real-time control applications in industries like automation and telecommunications.[41] In the 1980s, Modula-3 emerged as a collaborative effort involving researchers from Digital Equipment Corporation, Olivetti, and SRC, extending Modula-2 with object-oriented features and exception handling; however, Wirth's direct involvement was limited to foundational influences rather than active design.[42]Oberon System

Oberon is a general-purpose programming language first published in 1987 by Niklaus Wirth, evolving from Modula-2 to emphasize simplicity through a single-module paradigm where each module serves as the primary unit of compilation and organization, eliminating the need for multi-module definitions while incorporating automatic garbage collection for memory management.[43][44] This design reduced syntactic complexity from its predecessor, focusing on type extensibility for records to enable object-oriented programming, with features like type-bound procedures acting as methods and runtime type tests (e.g., the IS operator) supporting polymorphic behavior.[43][44] Project Oberon, undertaken by Wirth and Jürg Gutknecht from 1986 to 1991, produced a complete personal computing system integrating the Oberon language, a minimalist operating system, and a window manager, all implemented in 12,277 lines of Oberon code to demonstrate verifiable and efficient software construction for workstations.[22] The system featured object-oriented extensions such as dynamic type descriptors and message-passing interfaces for extensible components like persistent objects and libraries, alongside innovative display models using tiled, non-overlapping hierarchical viewers for text, menus, and graphics, managed through bitmapped frames and mouse-driven interactions.[22] This minimalistic approach prioritized essential functionality, such as a dynamic linker-loader and centralized resource managers for files and modules, avoiding bloat to ensure the entire environment could be comprehended and maintained by a small team.[22] The original implementation ran natively on the Ceres workstation, a custom hardware platform developed alongside the software, with later ports extending the system to other architectures through Native Oberon for x86 PCs, and successors like Bluebottle (also known as Active Oberon System) and A2, which evolved the design to support multiprocessing while preserving the core principles.[22] Throughout, the project embodied Wirth's philosophy of simplicity and verifiability, advocating for lean designs that facilitate understanding, debugging, and evolution without unnecessary features, as exemplified by the system's bootstrapping from a basic compiler to a full environment.[22][44]Other Contributions

Hardware Innovations

Niklaus Wirth's contributions to hardware design emphasized minimalism, efficiency, and tight integration with software systems, reflecting his philosophy of simplicity in computing. During his tenure at ETH Zurich, Wirth led the development of the Lilith workstation starting in 1978, with prototypes completed by 1980, and in use through the early 1980s, a pioneering personal computer optimized for structured programming environments.[18] The Lilith featured a custom 16-bit processor built using AMD 2901 bit-slice components, enabling direct execution of Modula-2 code through microcode implementation.[19] It included a high-resolution monochrome bit-mapped display (704 × 928 pixels in portrait orientation), mouse input for graphical interaction, and support for networked operation via Ethernet, making it one of the earliest workstations to incorporate these elements in an academic setting.[45] The system's hardware was designed with a focus on compactness and cost-effectiveness using bit-slice technology, with several hundred units produced primarily for educational use at ETH.[46] Building on Lilith's foundation, Wirth's group developed the Ceres workstation starting in 1985, with the first series introduced in 1986, specifically tailored for the Oberon operating system and programming environment.[22] Ceres utilized a National Semiconductor NS32032 32-bit microprocessor running at 10 MHz, paired with a bit-mapped display of 1024x800 resolution, mouse and keyboard interfaces, RS-232 serial connectivity, and an RS-485 network for multi-user collaboration.[47] This design embodied Wirth's commitment to simplicity by focusing on essential components, resulting in a lean architecture that supported the entire Oberon system— including compiler, kernel, and applications—written in Oberon itself, without reliance on lower-level assembly.[22] With over 100 units built across models, they served as a platform for teaching operating systems and software engineering at ETH until the early 1990s.[48] Wirth's hardware innovations drew significant inspiration from his 1976–1977 sabbatical at Xerox PARC, where exposure to the Alto workstation influenced his vision for personal computing.[7] Unlike the resource-intensive Alto, however, Wirth emphasized minimalism in Lilith and Ceres, using custom silicon and bit-slice technology to create affordable, purpose-built systems rather than general-purpose machines burdened by excess features.[3] In the 2000s, Wirth extended this approach with the A2, a compact single-board computer designed for embedded applications running the Oberon system.[49] The A2 incorporated a simple RISC processor tailored to Oberon's needs, implemented on low-cost hardware to demonstrate scalable, efficient computing for resource-constrained environments.[50] Throughout these projects, Wirth advocated for hardware-software co-design, where the architecture directly supports the programming language and operating system to enhance performance and reduce complexity.[21] This principle, evident in the microcode-generated execution on Lilith and the unified Oberon implementation on Ceres, influenced subsequent workstation designs and underscored Wirth's belief that simplicity in both domains yields robust, maintainable systems.[51] His hardware efforts not only provided practical tools for ETH's curriculum but also demonstrated how integrated design could democratize advanced computing.[7]Software Engineering Principles

Niklaus Wirth was a prominent advocate for structured programming during the 1970s, emphasizing the use of control structures like sequence, selection, and iteration to replace unstructured practices such as goto statements, which he viewed as sources of error and complexity.[52] Influenced by and collaborating with pioneers like Edsger W. Dijkstra and Ole-Johan Dahl on structured programming principles, as outlined in the foundational text Structured Programming (1972) by Dahl, Dijkstra, and Hoare, Wirth's efforts helped shift programming paradigms away from ad hoc coding toward systematic methodologies, influencing educational curricula worldwide. Central to Wirth's philosophy was top-down design combined with stepwise refinement, a process he detailed in his seminal 1971 paper, where programs are developed by starting with a high-level specification and progressively refining it into detailed implementations through successive levels of abstraction.[53] This technique prioritizes modular decomposition, allowing developers to verify correctness at each step and manage complexity in large systems by focusing on one refinement at a time. Wirth argued that such methods not only facilitate debugging but also enhance verifiability, as each module can be tested independently before integration.[53] Wirth consistently stressed simplicity and verifiability as core tenets of software engineering, warning against the pitfalls of unnecessary complexity that obscure program logic and hinder maintenance. In his 1995 essay A Plea for Lean Software, he critiqued the growing trend of software bloat, where advancing hardware capabilities encouraged feature proliferation at the expense of efficiency and elegance, stating, "Software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster."[54] He advocated for designs that prioritize essential functionality, easy comprehension, and minimal resource use, principles he instilled in his teaching at ETH Zurich, where students were trained to build concise, reliable systems rather than elaborate ones.[55] These critiques of over-engineering extended to his classroom, where he demonstrated how bloated code leads to unmanageable projects, urging restraint to preserve software integrity.[56] Wirth made significant contributions to compiler construction techniques, promoting practical, straightforward methods like recursive descent parsing and single-pass code generation to create efficient tools without excessive optimization overhead. His 1996 textbook Compiler Construction exemplifies this approach, providing hands-on guidance for implementing compilers using simple, verifiable algorithms that align with his broader emphasis on lean design.[57] These techniques, derived from his work on languages like Pascal, underscored program derivation as an iterative process akin to stepwise refinement, where compilers themselves are built modularly to ensure correctness and adaptability. Wirth's principles of clarity, modularity, and documentation have influenced modern software practices, including literate programming, by promoting code as a readable narrative that integrates explanation with implementation for better long-term maintainability.[58]Wirth's Law

Wirth's Law, formulated by Niklaus Wirth in 1995, states that "software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster."[59] This observation highlights the phenomenon of software bloat, where increasing complexity and resource demands in programs outpace the performance gains from hardware advancements, such as those described by Moore's Law.[59] The law originated from Wirth's analysis of trends in computing from the 1970s through the 1990s, during which he witnessed exponential growth in software size and inefficiency despite rapid hardware improvements.[59] For instance, in the early 1970s, a basic text editor required only about 8,000 bytes of memory, while by the mid-1990s, similar tools demanded around 800,000 bytes, often running slower on much faster machines.[59] Compilers followed a similar pattern, expanding from roughly 32,000 bytes to several megabytes, and operating systems grew from 8,000 bytes to vast multi-megabyte installations, incorporating non-essential features like graphical interfaces that added overhead without proportional benefits.[59] These examples illustrate a contrast with hardware progress: while processor speeds and memory capacities doubled approximately every 18 to 24 months under Moore's Law, software inefficiencies—driven by unchecked feature addition and poor optimization—eroded these gains, leading to systems that felt no faster or even slower for everyday tasks.[59] The implications of Wirth's Law emphasize the need for disciplined software design to combat bloat, advocating for simplicity, modularity, and focus on essential functionality to ensure that hardware advancements translate into real performance improvements.[59] Wirth illustrated this through projects like Oberon, a lean operating system and language implementation that fit within 200 kilobytes while remaining type-safe and efficient.[59] In his seminal essay "A Plea for Lean Software," Wirth warned that "software's girth has surpassed its functionality," urging developers to prioritize lean methodologies over expansive, resource-hungry designs.[59]Publications

Major Books

Niklaus Wirth's major books reflect his emphasis on clarity, structure, and practical implementation in programming, often serving as both pedagogical tools and references for his designed languages. His works prioritize systematic approaches to software development, drawing on examples from languages like Pascal and its successors to illustrate core concepts. One of Wirth's seminal contributions is Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs (1976, Prentice-Hall), which presents a systematic framework for program design by integrating algorithms and data structures as the foundation of effective software. The book uses Pascal to exemplify structured programming techniques, emphasizing modularity, abstraction, and stepwise refinement to foster reliable code. Its impact lies in shaping computer science education, promoting the idea that programs emerge directly from well-chosen algorithms and data representations, a principle that influenced generations of textbooks and curricula.[60] In the same year, Wirth published Compilerbau (Teubner Verlag, 1976), a concise guide to compiler construction that details the principles and implementation of translators for high-level languages. Drawing on his experience with the Pascal P compiler, the text covers lexical analysis, syntax parsing, semantic checking, and code generation in a methodical, top-down manner, using extended BNF notation for grammar descriptions. This work became a standard reference for compiler education due to its clarity and focus on efficiency, inspiring compact implementations like the original Pascal compiler at ETH Zurich.[61][7] The PASCAL User Manual and Report (Springer, 1975, co-authored with Kathleen Jensen), available in French translations such as PASCAL: manuel de l'utilisateur, serves as an introductory teaching text for the Pascal language, explaining its syntax, semantics, and use in structured programming. The book provides practical examples and exercises to introduce procedural programming concepts, including control structures, data types, and modular design, making it accessible for students transitioning from basic algorithmics. Its role in popularizing Pascal as an educational tool helped establish the language as a staple in computing courses worldwide during the 1970s and 1980s.[62][63] During the 1980s, Wirth authored several textbooks on Modula-2, notably Programming in Modula-2 (Springer, 1982, with later editions up to 1988), which offer detailed references to the language's features for modular and concurrent programming. These works explore Modula-2's extensions beyond Pascal, such as separate compilation, modules for information hiding, and low-level facilities, with applications in system programming and real-time systems. Widely adopted in academic settings, they reinforced Modula-2's use as a teaching language, bridging high-level abstraction with hardware awareness.[64] A later highlight is Project Oberon (1992, Addison-Wesley, co-authored with Jürg Gutknecht), which documents the complete design and implementation of the Oberon operating system, compiler, and associated hardware for a workstation. The book details the integrated environment's architecture, including object-oriented extensions in the Oberon language, display management, and resource handling, all coded in under 10,000 lines for simplicity and portability. This work exemplifies Wirth's philosophy of lean, self-contained systems and has influenced modern minimalistic OS designs and embedded systems research.[22]Selected Articles and Papers

Niklaus Wirth's early contributions to programming language design are exemplified in his 1968 paper "PL/360, a Programming Language for the 360 Computers," published in the Journal of the ACM, which introduced PL/360 as a low-level language tailored for IBM System/360 computers, providing symbolic assembly-like facilities while incorporating structured syntax defined recursively to enhance readability and maintainability.[65] This work addressed the limitations of machine-specific assembly languages by offering a more portable and expressive alternative, influencing subsequent systems programming efforts.[65] Complementing this, Wirth co-authored two-part paper series on the Euler language in Communications of the ACM in 1966, titled "EULER: A Generalization of ALGOL and Its Formal Definition: Part I" and "Part II," which extended ALGOL's concepts to create a more flexible language supporting dynamic data structures and orthogonal features, while providing a formal BNF-based definition to ensure unambiguous implementation.[66][27] These papers emphasized simplicity and generality, serving as a foundation for teaching compiler construction and influencing languages like Simula.[66] In the 1970s, Wirth focused on compiler design, notably in his 1971 paper "The Design of a Pascal Compiler," published in Software: Practice and Experience, which detailed a one-pass compilation strategy for Pascal that balanced efficiency with code quality through recursive descent parsing and minimal optimization passes. This approach demonstrated how compiler simplicity could yield portable and reliable implementations across diverse hardware, prioritizing developer productivity over exhaustive optimizations. Another key work from this period, "Program Development by Stepwise Refinement," in Communications of the ACM (1971), advocated for modular, top-down program construction using refinement steps to build complexity incrementally, establishing a cornerstone methodology for structured programming. Wirth's 1995 article "A Plea for Lean Software," in IEEE Computer, critiqued the growing complexity of software driven by hardware advances, famously stating that "software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster"—a principle now known as Wirth's Law—and urged developers to prioritize efficiency, simplicity, and functionality over feature bloat.[67] This paper highlighted empirical observations from systems like Unix and Windows, calling for disciplined design to counteract exponential growth in code size and execution time.[67] Reflecting on open systems in the 1990s, Wirth's work on Oberon included discussions in related publications emphasizing freedom from proprietary constraints, as seen in his contributions to the Oberon system documentation, which promoted an integrated, extensible environment free of layered dependencies to foster experimentation and portability. Post-retirement, Wirth turned to digital design and education, authoring "Hardware Compilation: Translating Programs into Circuits" in IEEE Computer (1998), which explored field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) for synthesizing hardware from high-level descriptions, bridging software and hardware paradigms to enable rapid prototyping. In education, his 2002 paper "Computing Science Education: The Road not Taken," presented at the Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education conference (ITiCSE), critiqued curriculum overload and advocated for focused teaching on core principles like abstraction and simplicity, drawing from his Oberon experiences to promote hands-on system building over tool proliferation.[68]Awards and Honors

Turing Award and Major Prizes

Niklaus Wirth received the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) A.M. Turing Award in 1984, the most prestigious honor in computer science, often called the "Nobel Prize of Computing," for his foundational work in programming language design.[3] The award citation specifically commended him "for developing a sequence of innovative computer languages, EULER, ALGOL W, MODULA, and particularly PASCAL," highlighting how these languages advanced structured programming and influenced software development practices worldwide.[3] The prize, which included a monetary award, was presented during the ACM Annual Conference in San Francisco in October 1984.[3] In his Turing Award acceptance lecture, titled "On the Design of Programming Languages," delivered at the conference, Wirth reflected on the evolution of his language projects and emphasized principles such as simplicity, orthogonality, and efficiency in language design to foster reliable and maintainable software.[69] This lecture underscored the impact of his contributions on compiler construction and portable programming environments, including his development of the P-code virtual machine for Pascal implementation across diverse hardware.[69] Among other major prizes, Wirth was awarded the IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award in 1983 for outstanding achievements in the field of information processing that advanced science and society.[70] In 1988, he received the IEEE Computer Pioneer Award, recognizing his pioneering innovations in both hardware and software, including the design of the Lilith workstation and contributions to RISC architectures.[71] Later, in 2007, the ACM Special Interest Group on Programming Languages (SIGPLAN) honored him with the Programming Languages Achievement Award for his enduring influence on the theory and practice of programming languages.[72]Other Recognitions

Wirth was elected a Fellow of the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) in 1994, recognizing his fundamental contributions to computer science.[73] He became a member of the Swiss Academy of Engineering Sciences (SATW) around 1993, affirming his influence on engineering and technology in Switzerland.[71][74] Wirth earned numerous honorary doctorates for his academic impact. These include:- University of York, England (1978)[75]

- École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland (1978)[75]

- Laval University, Quebec, Canada (1987)[75]

- Concordia University, Montreal, Canada (1989)[3]

- State University of St. Petersburg, Russia (1992)[3]

- Tel Aviv University, Israel (1993)[3]

- Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria (1993)[75]

- University of Novosibirsk, Russia (1996)[75]

- The Open University, England (1997)[75]

- University of Pretoria, South Africa (1998)[75]

- Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic (1999)[75]

- Saint Petersburg State University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (ITMO), Russia (2005)[75]

- Ural State University, Ekaterinburg, Russia (2005)[75]