Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Video random-access memory

View on Wikipedia

Video random-access memory (VRAM) is dedicated computer memory used to store the pixels and other graphics data as a framebuffer to be rendered on a computer monitor.[1] It often uses a different technology than other computer memory, in order to be read quickly for display on a screen.

Relation to GPUs

[edit]

Many modern GPUs rely on VRAM. In contrast, a GPU that does not use VRAM, and relies instead on system RAM, is said to have a unified memory architecture, or shared graphics memory.

System RAM and VRAM have been segregated due to the bandwidth requirements of GPUs,[2][3] and to achieve lower latency, since VRAM is physically closer to the GPU die.[4]

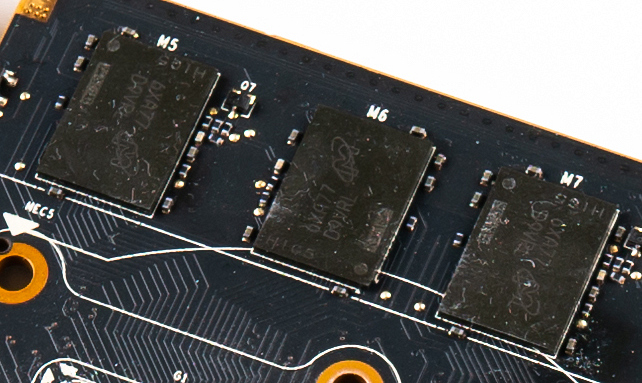

Modern VRAM is typically found in a BGA package[5] soldered onto a graphics card.[6] The VRAM is cooled along with the GPU by the GPU heatsink.[7]

Technologies

[edit]- Dual-ported video RAM, used in the 1990s and at the time often called "VRAM"

- SGRAM

- GDDR SDRAM

- High Bandwidth Memory (HBM)[8]

See also

[edit]- Graphics processing unit

- Tiled rendering, a method to reduce VRAM bandwidth requirements[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Foley, James D.; van Dam, Andries; Feiner, Steven K.; Hughes, John F. (1997). Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice. Addison-Wesley. p. 859. ISBN 0-201-84840-6.

- ^ "What is VRAM: The Memory Power Behind Real-time Ray-Tracing". Archived from the original on 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ "Relationship Between RAM and VRAM Bandwidth and Their Latency". 17 May 2021.

- ^ "RAM vs. VRAM: What's the Difference?". makeuseof.com. 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Encapsulated in CPUs, GPUs, RAM and Flash: Types and Uses". 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Graphics Card Components & Connectors Explained". 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Different Types of Graphics Card Cooling Solutions for GPU, VRAM & VRM". 17 January 2017.

- ^ "HBM Graphics Cards - 7 GPUs with HBM Memory". Axiom Gaming. 16 August 2025.

- ^ "GPU Framebuffer Memory: Understanding Tiling".