Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

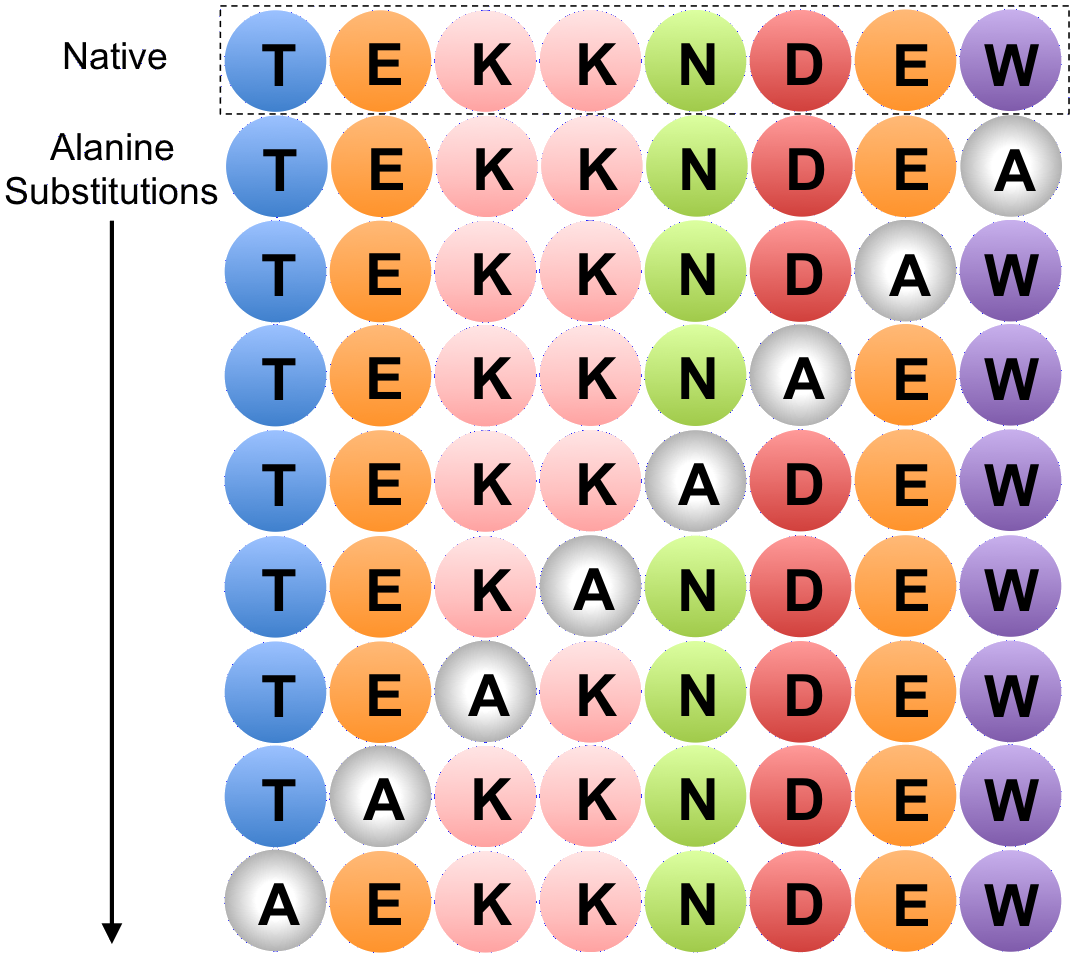

Alanine scanning

View on Wikipedia

In molecular biology, alanine scanning is a site-directed mutagenesis technique used to determine the contribution of a specific residue to the stability or function of a given protein.[1] Alanine is used because of its non-bulky, chemically inert, methyl functional group that nevertheless mimics the secondary structure preferences that many of the other amino acids possess. Sometimes bulky amino acids such as valine or leucine are used in cases where conservation of the size of mutated residues is needed.

This technique can also be used to determine whether the side chain of a specific residue plays a significant role in bioactivity. This is usually accomplished by site-directed mutagenesis or randomly by creating a PCR library. Furthermore, computational methods to estimate thermodynamic parameters based on theoretical alanine substitutions have been developed.

This technique is rapid, because many side chains are analyzed simultaneously and the need for protein purification and biophysical analysis is circumvented.[2] The technology is very mature at this point and is widely used in biochemical fields. The data can be tested by IR, NMR Spectroscopy, mathematical methods, bioassays, etc.[3][4][5]

One good example of alanine scanning is the examination of the role of charged residues on the surface of proteins.[6] In a systematic study on the roles of conserved charged residues on the surface of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), alanine scanning was used to reveal the importance of charged residues for the process of transport of the proteins to the cell surface.[6]

Applications

[edit]Alanine scanning was used to determine simultaneously the functional contributions of 19 side chains buried at the interface between human growth hormone and the extracellular domain of its receptor.[2] Each amino acid in the side chains was substituted by alanine. Then shotgun scanning method which combines the concepts of alanine scanning mutagenesis and binomial mutagenesis with phage display technology was used.

Another critical application of alanine scanning is to determine the influence of individual residues on structure and activity in the prototypic cyclotide kalata B1.[3] Cyclotides display a wide range of pharmaceutically important bioactivities, but their natural function is in plant defense as insecticidal agents. On the structure of cyclotides kalata B1, all 23 non-cysteine residues were successively substituted with alanine. The data were tested by NMR Spectroscopy.

In addition, alanine scanning is also used to determine which functional motif of Cry4Aa has the mosquitocidal activity.[4] Cry4Aa was produced by Bacillus thuringiensis. It is a dipteran-specific toxin and it plays an important role in how to produce a bioinsecticide to control mosquitoes. So, it is very essential to determine which functional motif of Cry4Aa contributes to this activity. In this study, several Cry4Aa mutants were made by replacing the residues of potential receptor binding site, loops 1, 2, and 3 in domain II with alanine. A bioassay Culex pipiens was followed to test the activities.

Alanine-World model

[edit]The alanine scanning method takes advantage of the fact that most canonical amino acids can be exchanged with Ala by point mutations, while the secondary structure of mutated protein remains intact, as Ala mimics the secondary structure preferences of the majority of the encoded or canonical amino acids. This is predicted by the Alanine-World model.

References

[edit]- ^ Morrison KL, Weiss GA (June 2001). "Combinatorial alanine-scanning". Curr Opin Chem Biol. 5 (3): 302–7. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(00)00206-4. PMID 11479122.

- ^ a b Weiss GA, Watanabe CK, Zhong A, Goddard A, Sidhu SS (August 2000). "Rapid mapping of protein functional epitopes by combinatorial alanine scanning". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (16): 8950–4. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.8950W. doi:10.1073/pnas.160252097. PMC 16802. PMID 10908667.

- ^ a b Simonsen SM, Sando L, Rosengren KJ, Wang CK, Colgrave ML, Daly NL, Craik DJ (April 2008). "Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the prototypic cyclotide reveals a cluster of residues essential for bioactivity". J. Biol. Chem. 283 (15): 9805–13. doi:10.1074/jbc.M709303200. PMID 18258598.

- ^ a b Howlader MT, Kagawa Y, Miyakawa A, Yamamoto A, Taniguchi T, Hayakawa T, Sakai H (February 2010). "Alanine scanning analyses of the three major loops in domain II of Bacillus thuringiensis mosquitocidal toxin Cry4Aa". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 (3): 860–5. Bibcode:2010ApEnM..76..860H. doi:10.1128/AEM.02175-09. PMC 2813026. PMID 19948851.

- ^ Gauguin L, Delaine C, Alvino CL, McNeil KA, Wallace JC, Forbes BE, De Meyts P (July 2008). "Alanine scanning of a putative receptor binding surface of insulin-like growth factor-I". J. Biol. Chem. 283 (30): 20821–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M802620200. PMC 3258947. PMID 18502759.

- ^ a b Edelheit O, Hanukoglu I, Dascal N, Hanukoglu A (April 2011). "Identification of the roles of conserved charged residues in the extracellular domain of an epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) subunit by alanine mutagenesis". Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 300 (4): F887–97. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00648.2010. PMID 21209000. S2CID 869654.

Further reading

[edit]- Michels CA (2002). Genetic techniques for biological research: a case study approach. London: J. Wiley. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-471-89921-1.