Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

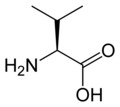

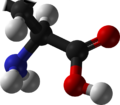

Valine

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Valine

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

2-Amino-3-methylbutanoic acid | |||

| Other names

2-Aminoisovaleric acid

Valic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChEMBL |

| ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank |

| ||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.703 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| |||

| KEGG |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[3] | |||

| C5H11NO2 | |||

| Molar mass | 117.148 g·mol−1 | ||

| Density | 1.316 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 298 °C (568 °F; 571 K) (decomposition) | ||

| soluble, 85 g/L [1] | |||

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.32 (carboxyl), 9.62 (amino)[2] | ||

| −74.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Valine (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Valine (symbol Val or V)[4] is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a side chain isopropyl group, making it a non-polar aliphatic amino acid. Valine is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it; it must be obtained from dietary sources which are foods that contain proteins, such as meats, dairy products, soy products, beans and legumes. It is encoded by all codons starting with GU (GUU, GUC, GUA, and GUG).

History and etymology

[edit]Valine was first isolated from casein in 1901 by Hermann Emil Fischer.[5] The name valine comes from its structural similarity to valeric acid, which in turn is named after the plant valerian due to the presence of the acid in the roots of the plant.[6][7]

Nomenclature

[edit]According to IUPAC, carbon atoms forming valine are numbered sequentially starting from 1 denoting the carboxyl carbon, whereas 4 and 4' denote the two terminal methyl carbons.[8]

Metabolism

[edit]Source and biosynthesis

[edit]Valine, like other branched-chain amino acids, is synthesized by bacteria and plants, but not by animals.[9] It is therefore an essential amino acid in animals, and needs to be present in the diet. Adult humans require about 24 mg/kg body weight daily.[10] It is synthesized in plants and bacteria via several steps starting from pyruvic acid. The initial part of the pathway also leads to leucine. The intermediate α-ketoisovalerate undergoes reductive amination with glutamate. Enzymes involved in this biosynthesis include:[11]

- Acetolactate synthase (also known as acetohydroxy acid synthase)

- Acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase

- Dihydroxyacid dehydratase

- Valine aminotransferase

Degradation

[edit]Like other branched-chain amino acids, the catabolism of valine starts with the removal of the amino group by transamination, giving alpha-ketoisovalerate, an alpha-keto acid, which is converted to isobutyryl-CoA through oxidative decarboxylation by the branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex.[12] This is further oxidised and rearranged to succinyl-CoA, which can enter the citric acid cycle and provide direct fuel in muscle tissue.[13][14]

Synthesis

[edit]Racemic valine can be synthesized by bromination of isovaleric acid followed by amination of the α-bromo derivative.[15]

Medical significance

[edit]Metabolic diseases

[edit]The degradation of valine is impaired in the following metabolic diseases:[citation needed]

- Combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria (CMAMMA)

- Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD)

- Methylmalonic acidemia

- Propionic acidemia

Insulin resistance

[edit]Lower levels of serum valine, like other branched-chain amino acids, are associated with weight loss and decreased insulin resistance: higher levels of valine are observed in the blood of diabetic mice, rats, and humans.[16] Mice fed a BCAA-deprived diet for one day had improved insulin sensitivity, and feeding of a valine-deprived diet for one week significantly decreases blood glucose levels.[17] In diet-induced obese and insulin resistant mice, a diet with decreased levels of valine and the other branched-chain amino acids resulted in a rapid reversal of the adiposity and an improvement in glucose-level control.[18] The valine catabolite 3-hydroxyisobutyrate promotes insulin resistance in mice by stimulating fatty acid uptake into muscle and lipid accumulation.[19] In mice, a BCAA-restricted diet decreased fasting blood glucose levels and improved body composition.[20]

Hematopoietic stem cells

[edit]Dietary valine is essential for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal, as demonstrated by experiments in mice.[21] Dietary valine restriction selectively depletes long-term repopulating HSC in mouse bone marrow. Successful stem cell transplantation was achieved in mice without irradiation after 3 weeks on a valine restricted diet. Long-term survival of the transplanted mice was achieved when valine was returned to the diet gradually over a 2-week period to avoid refeeding syndrome.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Physicochemical Information". emdmillipore. 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Dawson RM, Elliott DC, Elliott WH, Jones KM, eds. (1959). Data for Biochemical Research. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ASIN B000S6TFHA. OCLC 859821178.

- ^ Weast RC, ed. (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. C-569. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8.

- ^ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ "Valine". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Valine". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Valeric acid". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Jones JH, ed. (1985). Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins. Specialist Periodical Reports. Vol. 16. London: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-85186-144-9.

- ^ Basuchaudhuri P (2016). Nitrogen metabolism in rice. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-4987-4668-7. OCLC 945482059.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2002). "Protein and Amino Acids". Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 589–768. doi:10.17226/10490. ISBN 978-0-309-08537-3.

- ^ Lehninger, Albert L.; Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2000). Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 1-57259-153-6..

- ^ Mathews CK (2000). Biochemistry. Van Holde, K. E., Ahern, Kevin G. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, Calif.: Benjamin Cummings. p. 776. ISBN 978-0-8053-3066-3. OCLC 42290721.

- ^ "L-Valine". Stanford Chemicals. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ Kumari, Asha (2023). "Chapter 2 - Citric acid cycle". Sweet Biochemistry (5th ed.). Academic Press. pp. 9–15. ISBN 9780443153488.

- ^ Marvel CS (1940). "dl-Valine". Organic Syntheses. 20: 106; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 848..

- ^ Lynch CJ, Adams SH (December 2014). "Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 10 (12): 723–36. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.171. PMC 4424797. PMID 25287287.

- ^ Xiao F, Yu J, Guo Y, Deng J, Li K, Du Y, et al. (June 2014). "Effects of individual branched-chain amino acids deprivation on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in mice". Metabolism. 63 (6): 841–50. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2014.03.006. PMID 24684822.

- ^ Cummings NE, Williams EM, Kasza I, Konon EN, Schaid MD, Schmidt BA, et al. (February 2018). "Restoration of metabolic health by decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids". The Journal of Physiology. 596 (4): 623–645. doi:10.1113/JP275075. PMC 5813603. PMID 29266268.

- ^ Jang C, Oh SF, Wada S, Rowe GC, Liu L, Chan MC, et al. (April 2016). "A branched-chain amino acid metabolite drives vascular fatty acid transport and causes insulin resistance". Nature Medicine. 22 (4): 421–6. doi:10.1038/nm.4057. PMC 4949205. PMID 26950361.

- ^ Fontana L, Cummings NE, Arriola Apelo SI, Neuman JC, Kasza I, Schmidt BA, et al. (July 2016). "Decreased Consumption of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Improves Metabolic Health". Cell Reports. 16 (2): 520–530. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.092. PMC 4947548. PMID 27346343.

- ^ Taya Y, Ota Y, Wilkinson AC, Kanazawa A, Watarai H, Kasai M, et al. (December 2016). "Depleting dietary valine permits nonmyeloablative mouse hematopoietic stem cell transplantation". Science. 354 (6316): 1152–1155. Bibcode:2016Sci...354.1152T. doi:10.1126/science.aag3145. PMID 27934766. S2CID 45815137.