Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ammonia

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Ammonia[1]

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Azane | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 3587154 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.760 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 79 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Ammonia | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1005 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| NH3 | |||

| Molar mass | 17.031 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colourless gas | ||

| Odor | Strong pungent odour | ||

| Density |

| ||

| Melting point | −77.73 °C (−107.91 °F; 195.42 K) (Triple point at 6.060 kPa, 195.4 K) | ||

| Boiling point | −33.34 °C (−28.01 °F; 239.81 K) | ||

| Critical point (T, P) | 132.4 °C (405.5 K), 111.3 atm (11,280 kPa) | ||

| |||

| Solubility | soluble in chloroform, ether, ethanol, methanol | ||

| Vapor pressure | 857.3 kPa | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 32.5 (−33 °C),[6] 9.24 (of ammonium) | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.75 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Ammonium | ||

| Conjugate base | Amide | ||

| −18.0×10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.3327 | ||

| Viscosity |

| ||

| Structure | |||

| C3v | |||

| Trigonal pyramid | |||

| 1.42 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

193 J/(mol·K)[8] | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−46 kJ/mol[8] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling:[11] | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H314, H331, H410 | |||

| P260, P273, P280, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340+P311, P305+P351+P338+P310 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| 651 °C (1,204 °F; 924 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 15.0–33.6% | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

350 mg/kg (rat, oral)[9] | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

| ||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

| ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits):[12] | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

50 ppm (25 ppm ACGIH-TLV; 35 ppm STEL) | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 25 ppm (18 mg/m3) ST 35 ppm (27 mg/m3) | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

300 ppm | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0414 (anhydrous) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related nitrogen hydrides

|

|||

Related compounds

|

|||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Ammonia (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula NH3. A stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pungent smell.[13] It is widely used in fertilizers, refrigerants, explosives, cleaning agents, and is a precursor for numerous chemicals.[13] Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous waste, and it contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to fertilisers.[14] Around 70% of ammonia produced industrially is used to make fertilisers[15] in various forms and composition, such as urea and diammonium phosphate. Ammonia in pure form is also applied directly into the soil.

Ammonia, either directly or indirectly, is also a building block for the synthesis of many chemicals. In many countries, it is classified as an extremely hazardous substance.[16] Ammonia is toxic, causing damage to cells and tissues. For this reason it is excreted by most animals in the urine, in the form of dissolved urea.

Ammonia is produced biologically in a process called nitrogen fixation, but even more is generated industrially by the Haber process. The process helped revolutionize agriculture by providing cheap fertilizers. The global industrial production of ammonia in 2021 was 235 million tonnes.[17][18] Industrial ammonia is transported by road in tankers, by rail in tank wagons, by sea in gas carriers, or in cylinders.[19] Ammonia occurs in nature and has been detected in the interstellar medium.

Ammonia boils at −33.34 °C (−28.012 °F) at a pressure of one atmosphere, but the liquid can often be handled in the laboratory without external cooling. Household ammonia or ammonium hydroxide is a solution of ammonia in water.

Etymology

[edit]The name ammonia is derived from the name of the Egyptian deity Amun (Ammon in Greek) since priests and travelers of those temples would burn soils rich in ammonium chloride, which came from animal dung and urine.[13] Pliny, in Book XXXI of his Natural History, refers to a salt named hammoniacum, so called because of the proximity of its source to the Temple of Jupiter Amun (Greek Ἄμμων Ammon) in the Roman province of Cyrenaica.[20] However, the description Pliny gives of the salt does not conform to the properties of ammonium chloride. According to Herbert Hoover's commentary in his English translation of Georgius Agricola's De re metallica, it is likely to have been common sea salt.[21] In any case, that salt ultimately gave ammonia and ammonium compounds their name.

Natural occurrence (abiological)

[edit]Traces of ammonia/ammonium are found in rainwater. Ammonium chloride (sal ammoniac), and ammonium sulfate are found in volcanic districts. Crystals of ammonium bicarbonate have been found in Patagonia guano.[22]

Ammonia is found throughout the Solar System on Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto, among other places: on smaller, icy bodies such as Pluto, ammonia can act as a geologically important antifreeze, as a mixture of water and ammonia can have a melting point as low as −100 °C (−148 °F; 173 K) if the ammonia concentration is high enough and thus allow such bodies to retain internal oceans and active geology at a far lower temperature than would be possible with water alone.[23][24] Substances containing ammonia, or those that are similar to it, are called ammoniacal.[25]

Properties

[edit]Ammonia is a colourless gas with a characteristically pungent smell. It is lighter than air, its density being 0.589 times that of air. It is easily liquefied due to the strong hydrogen bonding between molecules. Gaseous ammonia turns to a colourless liquid, which boils at −33.1 °C (−27.58 °F), and freezes to colourless crystals[22] at −77.7 °C (−107.86 °F). Little data is available at very high temperatures and pressures, but the liquid-vapor critical point occurs at 405 K and 11.35 MPa.[26]

Solid

[edit]The crystal symmetry is cubic, Pearson symbol cP16, space group P213 No.198, lattice constant 0.5125 nm.[27]

Liquid

[edit]Liquid ammonia possesses strong ionising powers reflecting its high ε of 22 at −35 °C (−31 °F).[28] Liquid ammonia has a very high standard enthalpy change of vapourization (23.5 kJ/mol;[29] for comparison, water's is 40.65 kJ/mol, methane 8.19 kJ/mol and phosphine 14.6 kJ/mol) and can be transported in pressurized or refrigerated vessels; however, at standard temperature and pressure liquid anhydrous ammonia will vaporize.[30]

Solvent properties

[edit]Ammonia readily dissolves in water. In an aqueous solution, it can be expelled by boiling. The aqueous solution of ammonia is basic, and may be described as aqueous ammonia or ammonium hydroxide.[31] The maximum concentration of ammonia in water (a saturated solution) has a specific gravity of 0.880 and is often known as '.880 ammonia'.[32]

| Temperature (°C) |

Density (kg/m3) |

Specific heat (kJ/(kg·K)) |

Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) |

Thermal conductivity (W/(m·K)) |

Thermal diffusivity (m2/s) |

Prandtl Number |

Bulk modulus (K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −50 | 703.69 | 4.463 | 4.35×10−7 | 0.547 | 1.74×10−7 | 2.6 | |

| −40 | 691.68 | 4.467 | 4.06×10−7 | 0.547 | 1.78×10−7 | 2.28 | |

| −30 | 679.34 | 4.476 | 3.87×10−7 | 0.549 | 1.80×10−7 | 2.15 | |

| −20 | 666.69 | 4.509 | 3.81×10−7 | 0.547 | 1.82×10−7 | 2.09 | |

| −10 | 653.55 | 4.564 | 3.78×10−7 | 0.543 | 1.83×10−7 | 2.07 | |

| 0 | 640.1 | 4.635 | 3.73×10−7 | 0.540 | 1.82×10−7 | 2.05 | |

| 10 | 626.16 | 4.714 | 3.68×10−7 | 0.531 | 1.80×10−7 | 2.04 | |

| 20 | 611.75 | 4.798 | 3.59×10−7 | 0.521 | 1.78×10−7 | 2.02 | 2.45×10−3 |

| 30 | 596.37 | 4.89 | 3.49×10−7 | 0.507 | 1.74×10−7 | 2.01 | |

| 40 | 580.99 | 4.999 | 3.40×10−7 | 0.493 | 1.70×10−7 | 2 | |

| 50 | 564.33 | 5.116 | 3.30×10−7 | 0.476 | 1.65×10−7 | 1.99 |

| Temperature (K) |

Temperature (°C) | Density (kg/m3) |

Specific heat (kJ/(kg·K)) |

Dynamic viscosity (kg/(m·s)) |

Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) |

Thermal conductivity (W/(m·K)) |

Thermal diffusivity (m2/s) |

Prandtl Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 273 | −0.15 | 0.7929 | 2.177 | 9.35×10−6 | 1.18×10−5 | 0.0220 | 1.31×10−5 | 0.90 |

| 323 | 49.85 | 0.6487 | 2.177 | 1.10×10−5 | 1.70×10−5 | 0.0270 | 1.92×10−5 | 0.88 |

| 373 | 99.85 | 0.559 | 2.236 | 1.29×10−5 | 1.30×10−5 | 0.0327 | 2.62×10−5 | 0.87 |

| 423 | 149.85 | 0.4934 | 2.315 | 1.47×10−5 | 2.97×10−5 | 0.0391 | 3.43×10−5 | 0.87 |

| 473 | 199.85 | 0.4405 | 2.395 | 1.65×10−5 | 3.74×10−5 | 0.0467 | 4.42×10−5 | 0.84 |

| 480 | 206.85 | 0.4273 | 2.43 | 1.67×10−5 | 3.90×10−5 | 0.0492 | 4.74×10−5 | 0.822 |

| 500 | 226.85 | 0.4101 | 2.467 | 1.73×10−5 | 4.22×10−5 | 0.0525 | 5.19×10−5 | 0.813 |

| 520 | 246.85 | 0.3942 | 2.504 | 1.80×10−5 | 4.57×10−5 | 0.0545 | 5.52×10−5 | 0.827 |

| 540 | 266.85 | 0.3795 | 2.54 | 1.87×10−5 | 4.91×10−5 | 0.0575 | 5.97×10−5 | 0.824 |

| 560 | 286.85 | 0.3708 | 2.577 | 1.93×10−5 | 5.20×10−5 | 0.0606 | 6.34×10−5 | 0.827 |

| 580 | 306.85 | 0.3533 | 2.613 | 2.00×10−5 | 5.65×10−5 | 0.0638 | 6.91×10−5 | 0.817 |

Liquid ammonia is a widely studied nonaqueous ionising solvent. Its most conspicuous property is its ability to dissolve alkali metals to form highly coloured, electrically conductive solutions containing solvated electrons. Apart from these remarkable solutions, much of the chemistry in liquid ammonia can be classified by analogy with related reactions in aqueous solutions. Comparison of the physical properties of NH3 with those of water shows NH3 has the lower melting point, boiling point, density, viscosity, dielectric constant and electrical conductivity. These differences are attributed at least in part to the weaker hydrogen bonding in NH3. The ionic self-dissociation constant of liquid NH3 at −50 °C is about 10−33.

| Solubility (g of salt per 100 g liquid NH3) | |

|---|---|

| Ammonium acetate | 253.2 |

| Ammonium nitrate | 389.6 |

| Lithium nitrate | 243.7 |

| Sodium nitrate | 97.6 |

| Potassium nitrate | 10.4 |

| Sodium fluoride | 0.35 |

| Sodium chloride | 157.0 |

| Sodium bromide | 138.0 |

| Sodium iodide | 161.9 |

| Sodium thiocyanate | 205.5 |

Liquid ammonia is an ionising solvent, although less so than water, and dissolves a range of ionic compounds, including many nitrates, nitrites, cyanides, thiocyanates, metal cyclopentadienyl complexes and metal bis(trimethylsilyl)amides.[33] Most ammonium salts are soluble and act as acids in liquid ammonia solutions. The solubility of halide salts increases from fluoride to iodide. A saturated solution of ammonium nitrate (Divers' solution, named after Edward Divers) contains 0.83 mol solute per mole of ammonia and has a vapour pressure of less than 1 bar even at 25 °C (77 °F). However, few oxyanion salts with other cations dissolve.[35]

Liquid ammonia will dissolve all of the alkali metals and other electropositive metals such as Ca,[36] Sr, Ba, Eu and Yb (also Mg using an electrolytic process[34]). At low concentrations (<0.06 mol/L), deep blue solutions are formed: these contain metal cations and solvated electrons, free electrons that are surrounded by a cage of ammonia molecules.

These solutions are strong reducing agents. At higher concentrations, the solutions are metallic in appearance and in electrical conductivity. At low temperatures, the two types of solution can coexist as immiscible phases.

Redox properties of liquid ammonia

[edit]

| E° (V, ammonia) | E° (V, water) | |

|---|---|---|

| Li+ + e− ⇌ Li | −2.24 | −3.04 |

| K+ + e− ⇌ K | −1.98 | −2.93 |

| Na+ + e− ⇌ Na | −1.85 | −2.71 |

| Zn2+ + 2 e− ⇌ Zn | −0.53 | −0.76 |

| 2 [NH4]+ + 2 e− ⇌ H2 + 2 NH3 | 0.00 | — |

| Cu2+ + 2 e− ⇌ Cu | +0.43 | +0.34 |

| Ag+ + e− ⇌ Ag | +0.83 | +0.80 |

The range of thermodynamic stability of liquid ammonia solutions is very narrow, as the potential for oxidation to dinitrogen, E° (N2 + 6 [NH4]+ + 6 e− ⇌ 8 NH3), is only +0.04 V. In practice, both oxidation to dinitrogen and reduction to dihydrogen are slow. This is particularly true of reducing solutions: the solutions of the alkali metals mentioned above are stable for several days, slowly decomposing to the metal amide and dihydrogen. Most studies involving liquid ammonia solutions are done in reducing conditions; although oxidation of liquid ammonia is usually slow, there is still a risk of explosion, particularly if transition metal ions are present as possible catalysts.

Structure

[edit]

The ammonia molecule has a trigonal pyramidal shape, as predicted by the valence shell electron pair repulsion theory (VSEPR theory) with an experimentally determined bond angle of 106.7°.[37] The central nitrogen atom has five outer electrons with an additional electron from each hydrogen atom. This gives a total of eight electrons, or four electron pairs that are arranged tetrahedrally. Three of these electron pairs are used as bond pairs, which leaves one lone pair of electrons. The lone pair repels more strongly than bond pairs; therefore, the bond angle is not 109.5°, as expected for a regular tetrahedral arrangement, but 106.7°.[37] This shape gives the molecule a dipole moment and makes it polar. The molecule's polarity, and especially its ability to form hydrogen bonds, makes ammonia highly miscible with water. The lone pair makes ammonia a base, a proton acceptor. Ammonia is moderately basic; a 1.0 M aqueous solution has a pH of 11.6, and if a strong acid is added to such a solution until the solution is neutral (pH = 7), 99.4% of the ammonia molecules are protonated. Temperature and salinity also affect the proportion of ammonium [NH4]+. The latter has the shape of a regular tetrahedron and is isoelectronic with methane.

The ammonia molecule readily undergoes nitrogen inversion at room temperature; a useful analogy is an umbrella turning itself inside out in a strong wind. The energy barrier to this inversion is 24.7 kJ/mol, and the resonance frequency is 23.79 GHz, corresponding to microwave radiation of a wavelength of 1.260 cm. The absorption at this frequency was the first microwave spectrum to be observed[38] and was used in the first maser.

Amphotericity

[edit]One of the most characteristic properties of ammonia is its basicity. Ammonia is considered to be a weak base. It combines with acids to form ammonium salts; thus, with hydrochloric acid it forms ammonium chloride (sal ammoniac); with nitric acid, ammonium nitrate, etc. Perfectly dry ammonia gas will not combine with perfectly dry hydrogen chloride gas; moisture is necessary to bring about the reaction.[39][40]

As a demonstration experiment under air with ambient moisture, opened bottles of concentrated ammonia and hydrochloric acid solutions produce a cloud of ammonium chloride, which seems to appear 'out of nothing' as the salt aerosol forms where the two diffusing clouds of reagents meet between the two bottles.

The salts produced by the action of ammonia on acids are known as the ammonium salts and all contain the ammonium ion ([NH4]+).[39]

Although ammonia is well known as a weak base, it can also act as an extremely weak acid. It is a protic substance and is capable of formation of amides (which contain the NH−2 ion). For example, lithium dissolves in liquid ammonia to give a blue solution (solvated electron) of lithium amide:

Self-dissociation

[edit]Like water, liquid ammonia undergoes molecular autoionisation to form its acid and base conjugates:

Ammonia often functions as a weak base, so it has some buffering ability. Shifts in pH will cause more or fewer ammonium cations (NH+4) and amide anions (NH−2) to be present in solution. At standard pressure and temperature,

Combustion

[edit]Ammonia does not burn readily or sustain combustion, except under narrow fuel-to-air mixtures of 15–28% ammonia by volume in air.[41] When mixed with oxygen, it burns with a pale yellowish-green flame. Ignition occurs when chlorine is passed into ammonia, forming nitrogen and hydrogen chloride; if chlorine is present in excess, then the highly explosive nitrogen trichloride (NCl3) is also formed.

The combustion of ammonia to form nitrogen and water is exothermic:

The standard enthalpy change of combustion, ΔH°c, expressed per mole of ammonia and with condensation of the water formed, is −382.81 kJ/mol. Dinitrogen is the thermodynamic product of combustion: all nitrogen oxides are unstable with respect to N2 and O2, which is the principle behind the catalytic converter. Nitrogen oxides can be formed as kinetic products in the presence of appropriate catalysts, a reaction of great industrial importance in the production of nitric acid:

A subsequent reaction leads to NO2:

The combustion of ammonia in air is very difficult in the absence of a catalyst (such as platinum gauze or warm chromium(III) oxide), due to the relatively low heat of combustion, a lower laminar burning velocity, high auto-ignition temperature, high heat of vapourization, and a narrow flammability range. However, recent studies have shown that efficient and stable combustion of ammonia can be achieved using swirl combustors, thereby rekindling research interest in ammonia as a fuel for thermal power production.[42] The flammable range of ammonia in dry air is 15.15–27.35% and in 100% relative humidity air is 15.95–26.55%.[43][clarification needed] For studying the kinetics of ammonia combustion, knowledge of a detailed reliable reaction mechanism is required, but this has been challenging to obtain.[44]

Precursor to organonitrogen compounds

[edit]Ammonia is a direct or indirect precursor to most manufactured nitrogen-containing compounds. It is the precursor to nitric acid, which is the source for most N-substituted aromatic compounds.

Amines can be formed by the reaction of ammonia with alkyl halides or, more commonly, with alcohols:

Its ring-opening reaction with ethylene oxide give ethanolamine, diethanolamine, and triethanolamine.

Amides can be prepared by the reaction of ammonia with carboxylic acid and their derivatives. For example, ammonia reacts with formic acid (HCOOH) to yield formamide (HCONH2) when heated. Acyl chlorides are the most reactive, but the ammonia must be present in at least a twofold excess to neutralise the hydrogen chloride formed. Esters and anhydrides also react with ammonia to form amides. Ammonium salts of carboxylic acids can be dehydrated to amides by heating to 150–200 °C as long as no thermally sensitive groups are present.

- Amino acids, using Strecker amino-acid synthesis

- Acrylonitrile, in the Sohio process

Other organonitrogen compounds include alprazolam, ethanolamine, ethyl carbamate and hexamethylenetetramine.

Precursor to inorganic nitrogenous compounds

[edit]Nitric acid is generated via the Ostwald process by oxidation of ammonia with air over a platinum catalyst at 700–850 °C (1,292–1,562 °F), ≈9 atm. Nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide are intermediate in this conversion:[45]

Nitric acid is used for the production of fertilisers, explosives, and many organonitrogen compounds.

The hydrogen in ammonia is susceptible to replacement by a myriad substituents. Ammonia gas reacts with metallic sodium to give sodamide, NaNH2.[39]

With chlorine, monochloramine is formed.

Pentavalent ammonia is known as λ5-amine, nitrogen pentahydride decomposes spontaneously into trivalent ammonia (λ3-amine) and hydrogen gas at normal conditions. This substance was once investigated as a possible solid rocket fuel in 1966.[46]

Ammonia is also used to make the following compounds:

- Hydrazine, in the Olin Raschig process and the peroxide process

- Hydrogen cyanide, in the BMA process and the Andrussow process

- Hydroxylamine and ammonium carbonate, in the Raschig process

- Urea, in the Bosch–Meiser urea process and in Wöhler synthesis

- ammonium perchlorate, ammonium nitrate, and ammonium bicarbonate

Ammonia is a ligand forming metal ammine complexes. For historical reasons, ammonia is named ammine in the nomenclature of coordination compounds. One notable ammine complex is cisplatin (Pt(NH3)2Cl2, a widely used anticancer drug. Ammine complexes of chromium(III) formed the basis of Alfred Werner's revolutionary theory on the structure of coordination compounds. Werner noted only two isomers (fac- and mer-) of the complex [CrCl3(NH3)3] could be formed, and concluded the ligands must be arranged around the metal ion at the vertices of an octahedron.

Ammonia forms 1:1 adducts with a variety of Lewis acids such as I2, phenol, and Al(CH3)3. Ammonia is a hard base (HSAB theory) and its E & C parameters are EB = 2.31 and CB = 2.04. Its relative donor strength toward a series of acids, versus other Lewis bases, can be illustrated by C-B plots.

Detection and determination

[edit]Ammonia in solution

[edit]Ammonia and ammonium salts can be readily detected, in very minute traces, by the addition of Nessler's solution, which gives a distinct yellow colouration in the presence of the slightest trace of ammonia or ammonium salts. The amount of ammonia in ammonium salts can be estimated quantitatively by distillation of the salts with sodium (NaOH) or potassium hydroxide (KOH), the ammonia evolved being absorbed in a known volume of standard sulfuric acid and the excess of acid then determined volumetrically; or the ammonia may be absorbed in hydrochloric acid and the ammonium chloride so formed precipitated as ammonium hexachloroplatinate, [NH4]2[PtCl6].[47]

Gaseous ammonia

[edit]Sulfur sticks are burnt to detect small leaks in industrial ammonia refrigeration systems. Larger quantities can be detected by warming the salts with a caustic alkali or with quicklime, when the characteristic smell of ammonia will be at once apparent.[47] Ammonia is an irritant and irritation increases with concentration; the permissible exposure limit is 25 ppm, and lethal above 500 ppm by volume.[48] Higher concentrations are hardly detected by conventional detectors, the type of detector is chosen according to the sensitivity required (e.g. semiconductor, catalytic, electrochemical). Holographic sensors have been proposed for detecting concentrations up to 12.5% in volume.[49]

In a laboratorial setting, gaseous ammonia can be detected by using concentrated hydrochloric acid or gaseous hydrogen chloride. A dense white fume (which is ammonium chloride vapor) arises from the reaction between ammonia and HCl(g).[50]

Ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3–N)

[edit]Ammoniacal nitrogen (NH3–N) is a measure commonly used for testing the quantity of ammonium ions, derived naturally from ammonia, and returned to ammonia via organic processes, in water or waste liquids. It is a measure used mainly for quantifying values in waste treatment and water purification systems, as well as a measure of the health of natural and man-made water reserves. It is measured in units of mg/L (milligram per litre).

History

[edit]

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus mentioned that there were outcrops of salt in an area of Libya that was inhabited by a people called the 'Ammonians' (now the Siwa oasis in northwestern Egypt, where salt lakes still exist).[51][52] The Greek geographer Strabo also mentioned the salt from this region. However, the ancient authors Dioscorides, Apicius, Arrian, Synesius, and Aëtius of Amida described this salt as forming clear crystals that could be used for cooking and that were essentially rock salt.[53] Hammoniacus sal appears in the writings of Pliny,[54] although it is not known whether the term is equivalent to the more modern sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride).[22][55][56]

The fermentation of urine by bacteria produces a solution of ammonia; hence fermented urine was used in Classical Antiquity to wash cloth and clothing, to remove hair from hides in preparation for tanning, to serve as a mordant in dyeing cloth, and to remove rust from iron.[57] It was also used by ancient dentists to wash teeth.[58][59][60]

In the form of sal ammoniac (نشادر, nushadir), ammonia was important to the Muslim alchemists. It was mentioned in the Book of Stones, likely written in the 9th century and attributed to Jābir ibn Hayyān.[61] It was also important to the European alchemists of the 13th century, being mentioned by Albertus Magnus.[22] It was also used by dyers in the Middle Ages in the form of fermented urine to alter the colour of vegetable dyes. In the 15th century, Basilius Valentinus showed that ammonia could be obtained by the action of alkalis on sal ammoniac.[62] At a later period, when sal ammoniac was obtained by distilling the hooves and horns of oxen and neutralizing the resulting carbonate with hydrochloric acid, the name 'spirit of hartshorn' was applied to ammonia.[22][63]

Gaseous ammonia was first isolated by Joseph Black in 1756 by reacting sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride) with calcined magnesia (magnesium oxide).[64][65] It was isolated again by Peter Woulfe in 1767,[66][67] by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1770[68] and by Joseph Priestley in 1773 and was termed by him 'alkaline air'.[22][69] Eleven years later in 1785, Claude Louis Berthollet ascertained its composition.[70][22]

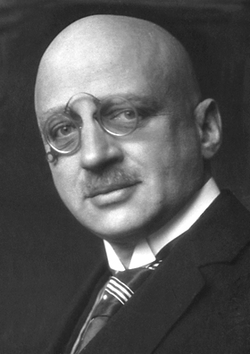

The production of ammonia from nitrogen in the air (and hydrogen) was invented by Fritz Haber and Robert LeRossignol. The patent was sent in 1909 (USPTO Nr 1,202,995) and awarded in 1916. Later, Carl Bosch developed the industrial method for ammonia production (Haber–Bosch process). It was first used on an industrial scale in Germany during World War I,[71] following the allied blockade that cut off the supply of nitrates from Chile. The ammonia was used to produce explosives to sustain war efforts.[72] The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1918 was awarded to Fritz Haber "for the synthesis of ammonia from its elements".

Before the availability of natural gas, hydrogen as a precursor to ammonia production was produced via the electrolysis of water or using the chloralkali process.

With the advent of the steel industry in the 20th century, ammonia became a byproduct of the production of coking coal.

Applications

[edit]Fertilizer

[edit]In the US as of 2019[update], approximately 88% of ammonia was used as fertilizers either as its salts, solutions or anhydrously.[73] When applied to soil, it helps provide increased yields of crops such as maize and wheat.[74] 30% of agricultural nitrogen applied in the US is in the form of anhydrous ammonia, and worldwide, 110 million tonnes are applied each year.[75] Solutions of ammonia ranging from 16% to 25% are used in the fermentation industry as a source of nitrogen for microorganisms and to adjust pH during fermentation.[76]

Refrigeration–R717

[edit]Because of ammonia's vapourization properties, it is a useful refrigerant.[71] It was commonly used before the popularisation of chlorofluorocarbons (Freons). Anhydrous ammonia is widely used in industrial refrigeration applications and hockey rinks because of its high energy efficiency and low cost. It suffers from the disadvantage of toxicity, and requiring corrosion resistant components, which restricts its domestic and small-scale use. Along with its use in modern vapour-compression refrigeration it is used in a mixture along with hydrogen and water in absorption refrigerators. The Kalina cycle, which is of growing importance to geothermal power plants, depends on the wide boiling range of the ammonia–water mixture.

Ammonia coolant is also used in the radiators aboard the International Space Station in loops that are used to regulate the internal temperature and enable temperature-dependent experiments.[77][78] The ammonia is under sufficient pressure to remain liquid throughout the process. Single-phase ammonia cooling systems also serve the power electronics in each pair of solar arrays.

The potential importance of ammonia as a refrigerant has increased with the discovery that vented CFCs and HFCs are potent and stable greenhouse gases.[79]

Antimicrobial agent for food products

[edit]As early as in 1895, it was known that ammonia was 'strongly antiseptic; it requires 1.4 grams per litre to preserve beef tea (broth).'[80] In one study, anhydrous ammonia destroyed 99.999% of zoonotic bacteria in three types of animal feed, but not silage.[81][82] Anhydrous ammonia is currently used commercially to reduce or eliminate microbial contamination of beef.[83][84] Lean finely textured beef (popularly known as 'pink slime') in the beef industry is made from fatty beef trimmings (c. 50–70% fat) by removing the fat using heat and centrifugation, then treating it with ammonia to kill E. coli. The process was deemed effective and safe by the US Department of Agriculture based on a study that found that the treatment reduces E. coli to undetectable levels.[85] There have been safety concerns about the process as well as consumer complaints about the taste and smell of ammonia-treated beef.[86]

Fuel

[edit]

Ammonia has been used as fuel, and is a proposed alternative to fossil fuels and hydrogen, especially in maritime transport. Being liquid at ambient temperature under its own vapour pressure and having high volumetric and gravimetric energy density, ammonia is considered a suitable carrier for hydrogen,[87] and may be cheaper than direct transport of liquid hydrogen.[88]

Compared to hydrogen, ammonia is easier to store. Compared to hydrogen as a fuel, ammonia is much more energy efficient, and could be produced, stored and delivered at a much lower cost than hydrogen, which must be kept compressed or as a cryogenic liquid.[89][90] The raw energy density of liquid ammonia is 11.5 MJ/L,[89] which is about a third that of diesel. Ammonia can also be converted back to hydrogen to be used to power hydrogen fuel cells, or it may be used directly within high-temperature solid oxide direct ammonia fuel cells to provide efficient power sources that do not emit greenhouse gases.[91][92] Ammonia to hydrogen conversion can be achieved through the sodium amide process[93] or the catalytic decomposition of ammonia using solid catalysts.[94]

Ammonia production currently creates 1.8% of global CO2 emissions. 'Green ammonia' is ammonia produced by using green hydrogen (hydrogen produced by electrolysis with electricity from renewable energy), whereas 'blue ammonia' is ammonia produced using blue hydrogen (hydrogen produced by steam methane reforming) where the carbon dioxide has been captured and stored.[95] In a world first in 2020, Saudi Arabia shipped 40 metric tons of liquid 'blue ammonia' to Japan for use as a fuel.[96] It was produced as a by-product by petrochemical industries, and can be burned without giving off greenhouse gases. Its energy density by volume is nearly double that of liquid hydrogen. If the process of creating it can be scaled up via purely renewable resources, producing green ammonia, it could make a major difference in avoiding climate change.[97]

Ships and maritime transport

[edit]Green ammonia is considered as a potential fuel for new ships, including future container ships. Ammonia is expected to increase in usage as a fuel source for shipping [98] The IEA forecasts that ammonia will meet approximately 45% of shipping fuel demands by 2050.[99]

In 2020, the companies DSME and MAN Energy Solutions announced the construction of an ammonia-based ship, DSME plans to commercialize it by 2025.[100] The use of ammonia as a potential alternative fuel for aircraft jet engines is also being explored.[101] In addition, hybrid engine configurations for supersonic aviation employing ammonia fuel have been investigated. [102] Japan is implementing a plan to develop ammonia co-firing technology that can increase the use of ammonia in power generation, as part of efforts to assist domestic and other Asian utilities to accelerate their transition to carbon neutrality.[103] In October 2021, the first International Conference on Fuel Ammonia (ICFA2021) was held.[104][105]

In June 2022, IHI Corporation succeeded in reducing greenhouse gases by over 99% during combustion of liquid ammonia in a 2,000-kilowatt-class gas turbine achieving truly CO2-free power generation.[106] In July 2022, Quad nations of Japan, the U.S., Australia and India agreed to promote technological development for clean-burning hydrogen and ammonia as fuels at the security grouping's first energy meeting.[107] As of 2022[update], however, significant amounts of NOx are produced.[108] Nitrous oxide may also be a problem as it is a "greenhouse gas that is known to possess up to 300 times the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of carbon dioxide".[109]

Vehicles, aviation and space

[edit]

Ammonia engines or ammonia motors, using ammonia as a working fluid, have been proposed and occasionally used.[110] The principle is similar to that used in a fireless locomotive, but with ammonia as the working fluid, instead of steam or compressed air. Ammonia engines were used experimentally in the 19th century by Goldsworthy Gurney in the UK and the St. Charles Streetcar Line in New Orleans in the 1870s and 1880s,[111] and during World War II ammonia was used to power buses in Belgium.[112]

Ammonia is sometimes proposed as a practical alternative to fossil fuel for internal combustion engines.[112][113][114][115] However, ammonia cannot be easily used in existing Otto cycle engines because of its very narrow flammability range. Despite this, several tests have been run.[116][117][118] Its high octane rating of 120[119] and low flame temperature[120] allows the use of high compression ratios without a penalty of high NOx production. Since ammonia contains no carbon, its combustion cannot produce carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, or soot. At high temperature and in the presence of a suitable catalyst ammonia decomposes into its constituent elements.[121] Decomposition of ammonia is a slightly endothermic process requiring 23 kJ/mol (5.5 kcal/mol) of ammonia, and yields hydrogen and nitrogen gas.

Rocket engines have also been fueled by ammonia. The Reaction Motors XLR99 rocket engine that powered the X-15 hypersonic research aircraft used liquid ammonia. Although not as powerful as other fuels, it left no soot in the reusable rocket engine, and its density approximately matches the density of the oxidiser, liquid oxygen, which simplified the aircraft's design.

Power stations

[edit]The company ACWA Power and the city of Neom have announced the construction of a green hydrogen and ammonia plant in 2020.[122]

Other

[edit]Remediation of gaseous emissions

[edit]Ammonia is used to scrub SO2 from the burning of fossil fuels, and the resulting product is converted to ammonium sulfate for use as fertiliser. Ammonia neutralises the nitrogen oxide (NOx) pollutants emitted by diesel engines. This technology, called SCR (selective catalytic reduction), relies on a vanadia-based catalyst.[123]

Ammonia may be used to mitigate gaseous spills of phosgene.[124]

Stimulant

[edit]

Ammonia, as the vapour released by smelling salts, has found significant use as a respiratory stimulant. Ammonia is commonly used in the illegal manufacture of methamphetamine through a Birch reduction.[126] The Birch method of making methamphetamine is dangerous because the alkali metal and liquid ammonia are both extremely reactive, and the temperature of liquid ammonia makes it susceptible to explosive boiling when reactants are added.[127]

Textile

[edit]Liquid ammonia is used for treatment of cotton materials, giving properties like mercerisation, using alkalis. In particular, it is used for prewashing of wool.[128]

Lifting gas

[edit]At standard temperature and pressure, ammonia is less dense than atmosphere and has approximately 45–48% of the lifting power of hydrogen or helium. Ammonia has sometimes been used to fill balloons as a lifting gas. Because of its relatively high boiling point (compared to helium and hydrogen), ammonia could potentially be refrigerated and liquefied aboard an airship to reduce lift and add ballast (and returned to a gas to add lift and reduce ballast).[129]

Fuming

[edit]Ammonia has been used to darken quartersawn white oak in Arts & Crafts and Mission-style furniture. Ammonia fumes react with the natural tannins in the wood and cause it to change colour.[130]

Cleaning agent

[edit]Ammonia is used as an ingredient in various cleaning products, such as Windex (until 2006), in the form of ammonia solution.

Safety

[edit]

The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set a 15-minute exposure limit for gaseous ammonia of 35 ppm by volume in the environmental air and an 8-hour exposure limit of 25 ppm by volume.[132] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recently reduced the IDLH (Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health, the level to which a healthy worker can be exposed for 30 minutes without suffering irreversible health effects) from 500 to 300 ppm based on recent more conservative interpretations of original research in 1943. Other organisations have varying exposure levels. US Navy Standards [U.S. Bureau of Ships 1962] maximum allowable concentrations (MACs): for continuous exposure (60 days) is 25 ppm; for exposure of 1 hour is 400 ppm.[133]

Ammonia vapour has a sharp, irritating, pungent odor that acts as a warning of potentially dangerous exposure. The average odor threshold is 5 ppm, well below any danger or damage. Exposure to very high concentrations of gaseous ammonia can result in lung damage and death.[132] Ammonia is regulated in the US as a non-flammable gas, but it meets the definition of a material that is toxic by inhalation and requires a hazardous safety permit when transported in quantities greater than 3,500 US gallons (13,000 L; 2,900 imp gal).[134]

Liquid ammonia is dangerous because it is hygroscopic and because it can cause caustic burns. See Gas carrier § Health effects of specific cargoes carried on gas carriers for more information.

Toxicity

[edit]The toxicity of ammonia solutions does not usually cause problems for humans and other mammals, as a specific mechanism exists to prevent its build-up in the bloodstream. Ammonia is converted to carbamoyl phosphate by the enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase, and then enters the urea cycle to be either incorporated into amino acids or excreted in the urine.[135] Fish and amphibians lack this mechanism, as they can usually eliminate ammonia from their bodies by direct excretion. Ammonia even at dilute concentrations is highly toxic to aquatic animals, and for this reason it is classified as "dangerous for the environment". Atmospheric ammonia plays a key role in the formation of fine particulate matter.[136]

Ammonia is a constituent of tobacco smoke.[137]

Coking wastewater

[edit]Ammonia is present in coking wastewater streams, as a liquid by-product of the production of coke from coal.[138] In some cases, the ammonia is discharged to the marine environment where it acts as a pollutant. The Whyalla Steelworks in South Australia is one example of a coke-producing facility that discharges ammonia into marine waters.[139]

Aquaculture

[edit]Ammonia toxicity is believed to be a cause of otherwise unexplained losses in fish hatcheries. Excess ammonia may accumulate and cause alteration of metabolism or increases in the body pH of the exposed organism. Tolerance varies among fish species.[140] At lower concentrations, around 0.05 mg/L, un-ionised ammonia is harmful to fish species and can result in poor growth and feed conversion rates, reduced fecundity and fertility and increase stress and susceptibility to bacterial infections and diseases.[141] Exposed to excess ammonia, fish may suffer loss of equilibrium, hyper-excitability, increased respiratory activity and oxygen uptake and increased heart rate.[140] At concentrations exceeding 2.0 mg/L, ammonia causes gill and tissue damage, extreme lethargy, convulsions, coma, and death.[140][142] Experiments have shown that the lethal concentration for a variety of fish species ranges from 0.2 to 2.0 mg/L.[142]

During winter, when reduced feeds are administered to aquaculture stock, ammonia levels can be higher. Lower ambient temperatures reduce the rate of algal photosynthesis so less ammonia is removed by any algae present. Within an aquaculture environment, especially at large scale, there is no fast-acting remedy to elevated ammonia levels. Prevention rather than correction is recommended to reduce harm to farmed fish[142] and in open water systems, the surrounding environment.

Storage information

[edit]Similar to propane, anhydrous ammonia boils below room temperature when at atmospheric pressure. A storage vessel capable of 250 psi (1.7 MPa) is suitable to contain the liquid.[143] Ammonia is used in numerous different industrial applications requiring carbon or stainless steel storage vessels. Ammonia with at least 0.2% by weight water content is not corrosive to carbon steel. NH3 carbon steel construction storage tanks with 0.2% by weight or more of water could last more than 50 years in service.[144] Experts warn that ammonium compounds not be allowed to come in contact with bases (unless in an intended and contained reaction), as dangerous quantities of ammonia gas could be released.

Laboratory

[edit]

The hazards of ammonia solutions depend on the concentration: 'dilute' ammonia solutions are usually 5–10% by weight (< 5.62 mol/L); 'concentrated' solutions are usually prepared at >25% by weight. A 25% (by weight) solution has a density of 0.907 g/cm3, and a solution that has a lower density will be more concentrated. The European Union classification of ammonia solutions is given in the table.

| Concentration by weight (w/w) |

Molarity | Concentration mass/volume (w/v) |

GHS pictograms | H-phrases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–10% | 2.87–5.62 mol/L | 48.9–95.7 g/L |

|

H314 |

| 10–25% | 5.62–13.29 mol/L | 95.7–226.3 g/L |

|

H314, H335, H400 |

| >25% | >13.29 mol/L | >226.3 g/L |

|

H314, H335, H400, H411 |

The ammonia vapour from concentrated ammonia solutions is severely irritating to the eyes and the respiratory tract, and experts warn that these solutions only be handled in a fume hood. Saturated ('0.880'–see § Properties) solutions can develop a significant pressure inside a closed bottle in warm weather, and experts also warn that the bottle be opened with care. This is not usually a problem for 25% ('0.900') solutions.

Experts warn that ammonia solutions not be mixed with halogens, as toxic and/or explosive products are formed. Experts also warn that prolonged contact of ammonia solutions with silver, mercury or iodide salts can also lead to explosive products: such mixtures are often formed in qualitative inorganic analysis, and that it needs to be lightly acidified but not concentrated (<6% w/v) before disposal once the test is completed.

Laboratory use of anhydrous ammonia (gas or liquid)

[edit]Anhydrous ammonia is classified as toxic (T) and dangerous for the environment (N). The gas is flammable (autoignition temperature: 651 °C) and can form explosive mixtures with air (16–25%). The permissible exposure limit (PEL) in the United States is 50 ppm (35 mg/m3), while the IDLH concentration is estimated at 300 ppm. Repeated exposure to ammonia lowers the sensitivity to the smell of the gas: normally the odour is detectable at concentrations of less than 50 ppm, but desensitised individuals may not detect it even at concentrations of 100 ppm. Anhydrous ammonia corrodes copper- and zinc-containing alloys, which makes brass fittings not appropriate for handling the gas. Liquid ammonia can also attack rubber and certain plastics.

Ammonia reacts violently with the halogens. Nitrogen triiodide, a primary high explosive, is formed when ammonia comes in contact with iodine. Ammonia causes the explosive polymerisation of ethylene oxide. It also forms explosive fulminating compounds with compounds of gold, silver, mercury, germanium or tellurium, and with stibine. Violent reactions have also been reported with acetaldehyde, hypochlorite solutions, potassium ferricyanide and peroxides.

Production

[edit]Ammonia has one of the highest rates of production of any inorganic chemical. Production is sometimes expressed in terms of "fixed nitrogen". Global production was estimated as being 160 million tonnes in 2020 (147 tons of fixed nitrogen).[146] China accounted for 26.5% of that, followed by Russia at 11.0%, the United States at 9.5%, and India at 8.3%.[146]

Before the start of World War I, most ammonia was obtained by the dry distillation[147] of nitrogenous vegetable and animal waste products, including camel dung, where it was distilled by the reduction of nitrous acid and nitrites with hydrogen; in addition, it was produced by the distillation of coal, and also by the decomposition of ammonium salts by alkaline hydroxides[148] such as quicklime:[22]

For small scale laboratory synthesis, one can heat urea and calcium hydroxide or sodium hydroxide:

Haber–Bosch

[edit]

The Haber process,[149] also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the main industrial procedure for the production of ammonia.[150][151] It converts atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by a reaction with hydrogen (H2) using finely divided iron metal as a catalyst:

This reaction is exothermic but disfavored in terms of entropy because four equivalents of reactant gases are converted into two equivalents of product gas. As a result, sufficiently high pressures and temperatures are needed to drive the reaction forward.

The German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the process in the first decade of the 20th century, and its improved efficiency over existing methods such as the Birkeland-Eyde and Frank-Caro processes was a major advancement in the industrial production of ammonia.[152][153][154]

The Haber process can be combined with steam reforming to produce ammonia with just three chemical inputs: water, natural gas, and atmospheric nitrogen. Both Haber and Bosch were eventually awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry: Haber in 1918 for ammonia synthesis specifically, and Bosch in 1931 for related contributions to high-pressure chemistry.Electrochemical

[edit]The electrochemical synthesis of ammonia involves the reductive formation of lithium nitride, which can be protonated to ammonia, given a proton source. The first use of this chemistry was reported in 1930, where lithium solutions in ethanol were used to produce ammonia at pressures of up to 1000 bar, with ethanol acting as the proton source.[155] Beyond simply mediating proton transfer to the nitrogen reduction reaction, ethanol has been found to play a multifaceted role, influencing electrolyte transformations and contributing to the formation of the solid electrolyte interphase, which enhances overall reaction efficiency.[156][157]

In 1994, Tsuneto et al. used lithium electrodeposition in tetrahydrofuran to synthesize ammonia at more moderate pressures with reasonable Faradaic efficiency.[158] Subsequent studies have further explored the ethanol–tetrahydrofuran system for electrochemical ammonia synthesis.[157][159]

In 2020, a solvent-agnostic gas diffusion electrode was shown to improve nitrogen transport to the reactive lithium. NH3 production rates of up to 30 ± 5 nmol/(s⋅cm2) and Faradaic efficiencies of up to 47.5 ± 4% at ambient temperature and 1 bar pressure were achieved.[160]

In 2021, it was demonstrated that ethanol could be replaced with a tetraalkyl phosphonium salt.[161] The study observed NH3 production rates of 53 ± 1 nmol/(s⋅cm2) at 69 ± 1% Faradaic efficiency experiments under 0.5 bar hydrogen and 19.5 bar nitrogen partial pressure at ambient temperature.[161] Technology based on this electrochemistry is being developed for commercial fertiliser and fuel production.[162][163]

In 2022, ammonia was produced via the lithium mediated process in a continuous-flow electrolyzer also demonstrating the hydrogen gas as proton source. The study synthesized ammonia at 61 ± 1% Faradaic efficiency at a current density of −6 mA/cm2 at 1 bar and room temperature.[164]

Biochemistry and medicine

[edit]

Ammonia is essential for life.[166] For example, it is required for the formation of amino acids and nucleic acids, fundamental building blocks of life. Ammonia is however quite toxic. Nature thus uses carriers for ammonia. Within a cell, glutamate serves this role. In the bloodstream, glutamine is a source of ammonia.[167]

Ethanolamine, required for cell membranes, is the substrate for ethanolamine ammonia-lyase, which produces ammonia:[168]

Ammonia is both a metabolic waste and a metabolic input throughout the biosphere. It is an important source of nitrogen for living systems. Although atmospheric nitrogen abounds (more than 75%), few living creatures are capable of using atmospheric nitrogen in its diatomic form, N2 gas. Therefore, nitrogen fixation is required for the synthesis of amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein. Some plants rely on ammonia and other nitrogenous wastes incorporated into the soil by decaying matter. Others, such as nitrogen-fixing legumes, benefit from symbiotic relationships with rhizobia bacteria that create ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen.[169]

In humans, inhaling ammonia in high concentrations can be fatal. Exposure to ammonia can cause headaches, edema, impaired memory, seizures and coma as it is neurotoxic in nature.[170]

Biosynthesis

[edit]In certain organisms, ammonia is produced from atmospheric nitrogen by enzymes called nitrogenases. The overall process is called nitrogen fixation. Intense effort has been directed toward understanding the mechanism of biological nitrogen fixation. The scientific interest in this problem is motivated by the unusual structure of the active site of the enzyme, which consists of an Fe7MoS9 ensemble.[171]

Ammonia is also a metabolic product of amino acid deamination catalyzed by enzymes such as glutamate dehydrogenase 1. Ammonia excretion is common in aquatic animals. In humans, it is quickly converted to urea (by liver), which is much less toxic, particularly less basic. This urea is a major component of the dry weight of urine. Most reptiles, birds, insects, and snails excrete uric acid solely as nitrogenous waste.

Physiology

[edit]Ammonia plays a role in both normal and abnormal animal physiology. It is biosynthesised through normal amino acid metabolism and is toxic in high concentrations. The liver converts ammonia to urea through a series of reactions known as the urea cycle. Liver dysfunction, such as that seen in cirrhosis, may lead to elevated amounts of ammonia in the blood (hyperammonemia). Likewise, defects in the enzymes responsible for the urea cycle, such as ornithine transcarbamylase, lead to hyperammonemia. Hyperammonemia contributes to the confusion and coma of hepatic encephalopathy, as well as the neurological disease common in people with urea cycle defects and organic acidurias.[172]

Ammonia is important for normal animal acid/base balance. After formation of ammonium from glutamine, α-ketoglutarate may be degraded to produce two bicarbonate ions, which are then available as buffers for dietary acids. Ammonium is excreted in the urine, resulting in net acid loss. Ammonia may itself diffuse across the renal tubules, combine with a hydrogen ion, and thus allow for further acid excretion.[173]

Excretion

[edit]Ammonium ions are a toxic waste product of metabolism in animals. In fish and aquatic invertebrates, it is excreted directly into the water. In mammals, sharks, and amphibians, it is converted in the urea cycle to urea, which is less toxic and can be stored more efficiently. In birds, reptiles, and terrestrial snails, metabolic ammonium is converted into uric acid, which is solid and can therefore be excreted with minimal water loss.[174]

Extraterrestrial occurrence

[edit]

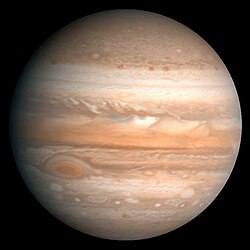

Ammonia has been detected in the atmospheres of the giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, along with other gases such as methane, hydrogen, and helium. The interior of Saturn may include frozen ammonia crystals.[175]

Interstellar space

[edit]Ammonia was first detected in interstellar space in 1968, based on microwave emissions from the direction of the galactic core.[176] This was the first polyatomic molecule to be so detected. The sensitivity of the molecule to a broad range of excitations and the ease with which it can be observed in a number of regions has made ammonia one of the most important molecules for studies of molecular clouds.[177] The relative intensity of the ammonia lines can be used to measure the temperature of the emitting medium.

The following isotopic species of ammonia have been detected: NH3,15NH3, NH2D, NHD2, and ND3. The detection of triply deuterated ammonia was considered a surprise as deuterium is relatively scarce. It is thought that the low-temperature conditions allow this molecule to survive and accumulate.[178]

Since its interstellar discovery, NH3 has proved to be an invaluable spectroscopic tool in the study of the interstellar medium. With a large number of transitions sensitive to a wide range of excitation conditions, NH3 has been widely astronomically detected–its detection has been reported in hundreds of journal articles. Listed below is a sample of journal articles that highlights the range of detectors that have been used to identify ammonia.

The study of interstellar ammonia has been important to a number of areas of research in the last few decades. Some of these are delineated below and primarily involve using ammonia as an interstellar thermometer.

Interstellar formation mechanisms

[edit]The interstellar abundance for ammonia has been measured for a variety of environments. The [NH3]/[H2] ratio has been estimated to range from 10−7 in small dark clouds[179] up to 10−5 in the dense core of the Orion molecular cloud complex.[180] Although a total of 18 total production routes have been proposed,[181] the principal formation mechanism for interstellar NH3 is the reaction:

The rate constant, k, of this reaction depends on the temperature of the environment, with a value of at 10 K.[182] The rate constant was calculated from the formula . For the primary formation reaction, a = 1.05×10−6 and B = −0.47. Assuming an NH+4 abundance of and an electron abundance of 10−7 typical of molecular clouds, the formation will proceed at a rate of 1.6×10−9 cm−3s−1 in a molecular cloud of total density 105 cm−3.[183]

All other proposed formation reactions have rate constants of between two and 13 orders of magnitude smaller, making their contribution to the abundance of ammonia relatively insignificant.[184] As an example of the minor contribution other formation reactions play, the reaction:

has a rate constant of 2.2×10−15. Assuming H2 densities of 105 and [NH2]/[H2] ratio of 10−7, this reaction proceeds at a rate of 2.2×10−12, more than three orders of magnitude slower than the primary reaction above.

Some of the other possible formation reactions are:

Interstellar destruction mechanisms

[edit]There are 113 total proposed reactions leading to the destruction of NH3. Of these, 39 were tabulated in extensive tables of the chemistry among C, N and O compounds.[185] A review of interstellar ammonia cites the following reactions as the principal dissociation mechanisms:[177]

| NH3 + [H3]+ → [NH4]+ + H2 | 1 |

| NH3 + HCO+ → [NH4]+ + CO | 2 |

with rate constants of 4.39×10−9[186] and 2.2×10−9,[187] respectively. The above equations (1, 2) run at a rate of 8.8×10−9 and 4.4×10−13, respectively. These calculations assumed the given rate constants and abundances of [NH3]/[H2] = 10−5, [[H3]+]/[H2] = 2×10−5, [HCO+]/[H2] = 2×10−9, and total densities of n = 105, typical of cold, dense, molecular clouds.[188] Clearly, between these two primary reactions, equation (1) is the dominant destruction reaction, with a rate ≈10,000 times faster than equation (2). This is due to the relatively high abundance of [H3]+.

Single antenna detections

[edit]Radio observations of NH3 from the Effelsberg 100-m Radio Telescope reveal that the ammonia line is separated into two components–a background ridge and an unresolved core. The background corresponds well with the locations previously detected CO.[189] The 25 m Chilbolton telescope in England detected radio signatures of ammonia in H II regions, HNH2O masers, H–H objects, and other objects associated with star formation. A comparison of emission line widths indicates that turbulent or systematic velocities do not increase in the central cores of molecular clouds.[190]

Microwave radiation from ammonia was observed in several galactic objects including W3(OH), Orion A, W43, W51, and five sources in the galactic centre. The high detection rate indicates that this is a common molecule in the interstellar medium and that high-density regions are common in the galaxy.[191]

Interferometric studies

[edit]VLA observations of NH3 in seven regions with high-velocity gaseous outflows revealed condensations of less than 0.1 pc in L1551, S140, and Cepheus A. Three individual condensations were detected in Cepheus A, one of them with a highly elongated shape. They may play an important role in creating the bipolar outflow in the region.[192]

Extragalactic ammonia was imaged using the VLA in IC 342. The hot gas has temperatures above 70 K, which was inferred from ammonia line ratios and appears to be closely associated with the innermost portions of the nuclear bar seen in CO.[193] NH3 was also monitored by VLA toward a sample of four galactic ultracompact HII regions: G9.62+0.19, G10.47+0.03, G29.96−0.02, and G31.41+0.31. Based upon temperature and density diagnostics, it is concluded that in general such clumps are probably the sites of massive star formation in an early evolutionary phase prior to the development of an ultracompact HII region.[194]

Infrared detections

[edit]Absorption at 2.97 micrometres due to solid ammonia was recorded from interstellar grains in the Becklin–Neugebauer Object and probably in NGC 2264-IR as well. This detection helped explain the physical shape of previously poorly understood and related ice absorption lines.[195]

A spectrum of the disk of Jupiter was obtained from the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, covering the 100 to 300 cm−1 spectral range. Analysis of the spectrum provides information on global mean properties of ammonia gas and an ammonia ice haze.[196]

A total of 149 dark cloud positions were surveyed for evidence of 'dense cores' by using the (J,K) = (1,1) rotating inversion line of NH3. In general, the cores are not spherically shaped, with aspect ratios ranging from 1.1 to 4.4. It is also found that cores with stars have broader lines than cores without stars.[197]

Ammonia has been detected in the Draco Nebula and in one or possibly two molecular clouds, which are associated with the high-latitude galactic infrared cirrus. The finding is significant because they may represent the birthplaces for the Population I metallicity B-type stars in the galactic halo that could have been borne in the galactic disk.[198]

Observations of nearby dark clouds

[edit]By balancing and stimulated emission with spontaneous emission, it is possible to construct a relation between excitation temperature and density. Moreover, since the transitional levels of ammonia can be approximated by a 2-level system at low temperatures, this calculation is fairly simple. This premise can be applied to dark clouds, regions suspected of having extremely low temperatures and possible sites for future star formation. Detections of ammonia in dark clouds show very narrow lines – indicative not only of low temperatures, but also of a low level of inner-cloud turbulence. Line ratio calculations provide a measurement of cloud temperature that is independent of previous CO observations. The ammonia observations were consistent with CO measurements of rotation temperatures of ≈10 K. With this, densities can be determined, and have been calculated to range between 104 and 105 cm−3 in dark clouds. Mapping of NH3 gives typical clouds sizes of 0.1 pc and masses near 1 solar mass. These cold, dense cores are the sites of future star formation.

UC HII regions

[edit]Ultra-compact HII regions are among the best tracers of high-mass star formation. The dense material surrounding UCHII regions is likely primarily molecular. Since a complete study of massive star formation necessarily involves the cloud from which the star formed, ammonia is an invaluable tool in understanding this surrounding molecular material. Since this molecular material can be spatially resolved, it is possible to constrain the heating/ionising sources, temperatures, masses, and sizes of the regions. Doppler-shifted velocity components allow for the separation of distinct regions of molecular gas that can trace outflows and hot cores originating from forming stars.

Extragalactic detection

[edit]Ammonia has been detected in external galaxies,[199][200] and by simultaneously measuring several lines, it is possible to directly measure the gas temperature in these galaxies. Line ratios imply that gas temperatures are warm (≈50 K), originating from dense clouds with sizes of tens of parsecs. This picture is consistent with the picture within our Milky Way galaxy – hot dense molecular cores form around newly forming stars embedded in larger clouds of molecular material on the scale of several hundred parsecs (giant molecular clouds; GMCs).

See also

[edit]- Ammonia (data page) – Chemical data page

- Ammonia fountain – Type of chemical demonstration

- Ammonia production – Overview of history and methods to produce NH3

- Ammonia solution – Chemical compound

- Cost of electricity by source – Comparison of costs of different electricity generation sources

- Forming gas – Mixture of hydrogen and nitrogen

- Haber process – Industrial process for ammonia production

- Hydrazine – Colorless flammable liquid with an ammonia-like odor

- Water purification – Process of removing impurities from water

References

[edit]- ^ "Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry IUPAC Recommendations 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Gases – Densities". The Engineering Toolbox. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Yost, Don M. (2007). "Ammonia and Liquid Ammonia Solutions". Systematic Inorganic Chemistry. Read Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4067-7302-6.

- ^ Blum, Alexander (1975). "On crystalline character of transparent solid ammonia". Radiation Effects and Defects in Solids. 24 (4): 277. Bibcode:1975RadEf..24..277B. doi:10.1080/00337577508240819.

- ^ "Ammonia". The American Chemical Society. 8 February 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Perrin, D. D. (1982). Ionisation Constants of Inorganic Acids and Bases in Aqueous Solution (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- ^ Iwasaki, Hiroji; Takahashi, Mitsuo (1968). "Studies on the transport properties of fluids at high pressure". The Review of Physical Chemistry of Japan. 38 (1).

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles (6th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. A22. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ "Ammonia, Anhydrous Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Ammonia". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ammonia.

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0028". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c Myers, Richard L. (2007). The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah (7 November 2017). "How many people does synthetic fertilizer feed?". Our World in Data. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Ammonia Technology Roadmap – Analysis". IEA. 11 October 2021.

- ^ "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities". United States: Government Printing Office.

- ^ "Global ammonia annual production capacity". Statistia.

- ^ "Mitsubishi Heavy Industries BrandVoice: Scaling Ammonia Production for the World's Food Supply". Forbes. 29 October 2021.

- ^ Shreve, R. Norris; Brink, Joseph (1977). Chemical Process Industries (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-07-057145-7.

- ^ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BOOK XXXI. REMEDIES DERIVED FROM THE AQUATIC PRODUCTION, CHAP. 39. (7.)—THE VARIOUS KINDS OF SALT; THE METHODS OF PREPARING IT, AND THE REMEDIES DERIVED FROM IT. TWO HUNDRED AND FOUR OBSERVATIONS THERE UPON". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Hoover, Herbert (1950). Georgius Agricola De Re Metallica – Translated from the first Latin edition of 1556. New York: Dover Publications. p. 560. ISBN 978-0-486-60006-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Chisholm 1911, p. 861.

- ^ Shannon, Francis Patrick (1938) Tables of the properties of aqua–ammonia solutions. Part 1 of The Thermodynamics of Absorption Refrigeration. Lehigh University studies. Science and technology series

- ^ An ammonia–water slurry may swirl below Pluto's icy surface. Purdue University (9 November 2015)

- ^ "ammoniacal (adj.)". Oxford English Dictionary. July 2023. doi:10.1093/OED/3565252514.

- ^ Pimputkar, Siddha; Nakamura, Shuji (January 2016). "Decomposition of supercritical ammonia and modeling of supercritical ammonia–nitrogen–hydrogen solutions with applicability toward ammonothermal conditions". The Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 107: 17–30. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2015.07.032.

- ^ Hewat, A. W.; Riekel, C. (1979). "The crystal structure of deuteroammonia between 2 and 180 K by neutron powder profile refinement". Acta Crystallographica Section A. 35 (4): 569. Bibcode:1979AcCrA..35..569H. doi:10.1107/S0567739479001340.

- ^ Billaud, Gerard; Demortier, Antoine (December 1975). "Dielectric constant of liquid ammonia from -35 to + 50.deg. and its influence on the association between solvated electrons and cation". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 79 (26): 3053–3055. doi:10.1021/j100593a053. ISSN 0022-3654.

- ^ Ammonia in Linstrom, Peter J.; Mallard, William G. (eds.); NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg (MD)

- ^ Jepsen, S. Dee; McGuire, Kent (27 November 2017). "Safe Handling of Anhydrous Ammonia". Ohio State University Extension.

- ^ "Medical Management Guidelines for Ammonia". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 12 January 2017.

- ^ Hawkins, Nehemiah (1909). Hawkins' Mechanical Dictionary: A Cyclopedia of Words, Terms, Phrases and Data Used in the Mechanic Arts, Trades and Sciences. T. Audel. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Neufeld, R.; Michel, R.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Schöne, R.; Stalke, D. (2016). "Introducing a Hydrogen-Bond Donor into a Weakly Nucleophilic Brønsted Base: Alkali Metal Hexamethyldisilazides (MHMDS, M = Li, Na, K, Rb and Cs) with Ammonia". Chem. Eur. J. 22 (35): 12340–12346. doi:10.1002/chem.201600833. PMID 27457218.

- ^ a b c Combellas, C; Kanoufi, F; Thiébault, A (2001). "Solutions of solvated electrons in liquid ammonia". Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 499: 144–151. doi:10.1016/S0022-0728(00)00504-0.

- ^ Audrieth, Ludwig F.; Kleinberg, Jacob (1953). Non-aqueous solvents. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 45. LCCN 52-12057.

- ^ Edwin M. Kaiser (2001). "Calcium–Ammonia". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rc003. ISBN 978-0-471-93623-7.

- ^ a b Haynes, William M., ed. (2013). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (94th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 9–26. ISBN 978-1-4665-7114-3.

- ^ Cleeton, C. E.; Williams, N. H. (1934). "Electromagnetic Waves of 1.1 cm (0 in). Wave-Length and the Absorption Spectrum of Ammonia". Physical Review. 45 (4): 234. Bibcode:1934PhRv...45..234C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.45.234.

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911, p. 862.

- ^ Baker, H. B. (1894). "Influence of moisture on chemical change". J. Chem. Soc. 65: 611–624. doi:10.1039/CT8946500611.

- ^ "Ammonia". PubChem.

- ^ Kobayashi, Hideaki; Hayakawa, Akihiro; Somarathne, K.D. Kunkuma A.; Okafor, Ekenechukwu C. (2019). "Science and technology of ammonia combustion". Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 37 (1): 109–133. Bibcode:2019PComI..37..109K. doi:10.1016/j.proci.2018.09.029.

- ^ Khan, A.S.; Kelley, R.D.; Chapman, K.S.; Fenton, D.L. (1995). Flammability limits of ammonia–air mixtures. U.S.: U.S. DOE Office of Scientific and Technical Information. OSTI 215703.

- ^ Shrestha, Krishna P.; Seidel, Lars; Zeuch, Thomas; Mauss, Fabian (7 July 2018). "Detailed kinetic mechanism for the oxidation of ammonia including the formation and reduction of nitrogen oxides" (PDF). Energy & Fuels. 32 (10): 10202–10217. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b01056. ISSN 0887-0624. S2CID 103854263. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Sterrett, K. F.; Caron, A. P. (1966). "High pressure chemistry of hydrogenous fuels". Northrop Space Labs. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911, p. 863.

- ^ (OSHA) Source: Sax, N. Irving (1984) Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. 6th Ed. Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0-442-28304-0.

- ^ Hurtado, J. L. Martinez; Lowe, C. R. (2014). "Ammonia-Sensitive Photonic Structures Fabricated in Nafion Membranes by Laser Ablation". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 6 (11): 8903–8908. doi:10.1021/am5016588. ISSN 1944-8244. PMID 24803236.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils; Eagleson, Mary; Brewer, William; Aylett, Bernhard J., eds. (2001). Holleman-Wiberg inorganic chemistry. San Diego, Calif. London: Academic. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ Herodotus with George Rawlinson, trans., The History of Herodotus (New York, New York: Tandy-Thomas Co., 1909), vol.2, Book 4, § 181, pp. 304–305.

- ^ The land of the Ammonians is mentioned elsewhere in Herodotus' History and in Pausanias' Description of Greece:

- Herodotus with George Rawlinson, trans., The History of Herodotus (New York, New York: Tandy-Thomas Co., 1909), vol. 1, Book 2, § 42, p. 245, vol. 2, Book 3, § 25, p. 73, and vol. 2, Book 3, § 26, p. 74.

- Pausanias with W.H.S. Jones, trans., Description of Greece (London, England: William Heinemann Ltd., 1979), vol. 2, Book 3, Ch. 18, § 3, pp. 109 and 111 and vol. 4, Book 9, Ch. 16, § 1, p. 239.

- ^ Kopp, Hermann, Geschichte der Chemie [History of Chemistry] (Braunschweig, (Germany): Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, 1845), Part 3, p. 237. [in German]

- ^ Chisholm 1911 cites Pliny Nat. Hist. xxxi. 39. See: Pliny the Elder with John Bostock and H. T. Riley, ed.s, The Natural History (London, England: H. G. Bohn, 1857), vol. 5, Book 31, § 39, p. 502.

- ^ "Sal-ammoniac". Webmineral. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Pliny also mentioned that when some samples of what was purported to be natron (Latin: nitrum, impure sodium carbonate) were treated with lime (calcium carbonate) and water, the natron would emit a pungent smell, which some authors have interpreted as signifying that the natron either was ammonium chloride or was contaminated with it. See:

- Pliny with W.H.S. Jones, trans., Natural History (London, England: William Heinemann Ltd., 1963), vol. 8, Book 31, § 46, pp. 448–449. From pp. 448–449: "Adulteratur in Aegypto calce, deprehenditur gusto. Sincerum enim statim resolvitur, adulteratum calce pungit et asperum [or aspersum] reddit odorem vehementer." (In Egypt it [i.e., natron] is adulterated with lime, which is detected by taste; for pure natron melts at once, but adulterated natron stings because of the lime, and emits a strong, bitter odour [or: when sprinkled [(aspersum) with water] emits a vehement odour])

- Kidd, John, Outlines of Mineralogy (Oxford, England: N. Bliss, 1809), vol. 2, p. 6.

- Moore, Nathaniel Fish, Ancient Mineralogy: Or, An Inquiry Respecting Mineral Substances Mentioned by the Ancients: ... (New York, New York: G. & C. Carvill & Co., 1834), pp. 96–97.

- ^ See:

- Forbes, R.J., Studies in Ancient Technology, vol. 5, 2nd ed. (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1966), pp. 19, 48, and 65.

- Moeller, Walter O., The Wool Trade of Ancient Pompeii (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1976), p. 20.

- Faber, G.A. (pseudonym of: Goldschmidt, Günther) (May 1938) "Dyeing and tanning in classical antiquity," Ciba Review, 9 : 277–312. Available at: Elizabethan Costume

- Smith, William, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London, England: John Murray, 1875), article: "Fullo" (i.e., fullers or launderers), pp. 551–553.

- Rousset, Henri (31 March 1917) "The laundries of the Ancients," Scientific American Supplement, 83 (2152) : 197.

- Bond, Sarah E., Trade and Taboo: Disreputable Professions in the Roman Mediterranean (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2016), p. 112.

- Binz, Arthur (1936) "Altes und Neues über die technische Verwendung des Harnes" (Ancient and modern [information] about the technological use of urine), Zeitschrift für Angewandte Chemie, 49 (23) : 355–360. [in German]

- Witty, Michael (December 2016) "Ancient Roman urine chemistry," Acta Archaeologica, 87 (1) : 179–191. Witty speculates that the Romans obtained ammonia in concentrated form by adding wood ash (impure potassium carbonate) to urine that had been fermented for several hours. Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) is thereby precipitated, and the yield of struvite can be increased by then treating the solution with bittern, a magnesium-rich solution that is a byproduct of making salt from sea water. Roasting struvite releases ammonia vapours.

- ^ Lenkeit, Roberta Edwards (23 October 2018). High Heels and Bound Feet: And Other Essays on Everyday Anthropology, Second Edition. Waveland Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4786-3841-4.

- ^ Perdigão, Jorge (3 August 2016). Tooth Whitening: An Evidence-Based Perspective. Springer. p. 170. ISBN 978-3-319-38849-6.

- ^ Bonitz, Michael; Lopez, Jose; Becker, Kurt; Thomsen, Hauke (9 April 2014). Complex Plasmas: Scientific Challenges and Technological Opportunities. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 465. ISBN 978-3-319-05437-7.

- ^ Haq, Syed Nomanul (1995). Names, Natures and Things: The Alchemist Jabir Ibn Hayyan and His Kitab Al-Ahjar (Book of Stones). Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-3254-1.

- ^ Spiritus salis urinæ (spirit of the salt of urine, i.e., ammonium carbonate) had apparently been produced before Valentinus, although he presented a new, simpler method for preparing it in his book: Valentinus, Basilius, Vier Tractätlein Fr. Basilii Valentini ... [Four essays of Brother Basil Valentine ... ] (Frankfurt am Main, (Germany): Luca Jennis, 1625), "Supplementum oder Zugabe" (Supplement or appendix), pp. 80–81: "Der Weg zum Universal, damit die drei Stein zusammen kommen." (The path to the Universal, so that the three stones come together.). From p. 81: "Der Spiritus salis Urinæ nimbt langes wesen zubereiten / dieser proceß aber ist waß leichter unnd näher auß dem Salz von Armenia, ... Nun nimb sauberen schönen Armenischen Salz armoniac ohn alles sublimiren / thue ihn in ein Kolben / giesse ein Oleum Tartari drauff / daß es wie ein Muß oder Brey werde / vermachs baldt / dafür thu auch ein grosen vorlag / so lege sich als baldt der Spiritus Salis Urinæ im Helm an Crystallisch ... " (Spirit of the salt of urine [i.e., ammonium carbonate] requires a long method [i.e., procedure] to prepare; this [i.e., Valentine's] process [starting] from the salt from Armenia [i.e., ammonium chloride], however, is somewhat easier and shorter ... Now take clean nice Armenian salt, without sublimating all [of it]; put it in a [distillation] flask; pour oil of tartar [i.e., potassium carbonate that has dissolved only in the water that it has absorbed from the air] on it, [so] that it [i.e., the mixture] becomes like a mush or paste; assemble it [i.e., the distilling apparatus (alembic)] quickly; for that [purpose] connect a large receiving flask; then soon spirit of the salt of urine deposits as crystals in the "helmet" [i.e., the outlet for the vapours, which is atop the distillation flask] ...)

See also: Kopp, Hermann, Geschichte der Chemie [History of Chemistry] (Braunschweig, (Germany): Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, 1845), Part 3, p. 243. [in German] - ^ Maurice P. Crosland (2004). Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry. Courier Dover Publications. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-486-43802-3.

- ^ Black, Joseph (1893) [1755]. Experiments upon magnesia alba, quick-lime, and other alcaline substances. Edinburgh: W.F. Clay.

- ^ Jacobson, Mark Z. (23 April 2012). Air Pollution and Global Warming: History, Science, and Solutions. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-69115-5.

- ^ "Woulfe's bottle". Chemistry World. Retrieved 1 July 2017.