Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Benjamin Milam

View on WikipediaBenjamin Rush Milam (October 20, 1788 – December 7, 1835) was an American colonist of Mexican Texas and a military leader and hero of the Texas Revolution. A native of what is now Kentucky, Milam fought beside American interests during the Mexican War of Independence and later joined the Texians in their own fight for independence, for which he assumed a leadership role. Persuading the weary Texians not to back down during the Siege of Béxar, Milam was killed in action while leading an assault into the city that eventually resulted in the Mexican Army's surrender. Milam County, Texas and the town of Milam are named in his honor, as are many other placenames and civic works throughout Texas.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Ben Milam was born in Frankfort, Kentucky on October 20, 1788, when Kentucky was still considered part of Virginia.[1] He was the fifth of six children born to Moses Milam and his wife, Elizabeth Pattie Boyd. Raised in the remote western frontier of the early United States, Milam had little formal schooling. As a young man, he enlisted as a private in the 8th Regiment of the Kentucky Militia and eventually was commissioned a lieutenant. He served in the War of 1812.[2]

Early years in Texas

[edit]In 1818, after learning of the trading opportunities with the Native Americans living along the upper Red River, Milam traveled from Kentucky to Spanish Texas to trade with the Comanche.[1][2] While there, he met David G. Burnet, who at the time was living with the Indians in an attempt to recover from a case of tuberculosis.[2]

In New Orleans in 1819, Milam met José Félix Trespalacios and James Long, who intended to lead a filibustering expedition to Texas to help Mexican revolutionaries in their ongoing fight for independence from Spain.[2] Milam decided to join the pair on what became known as the Long Expedition.[1][2]

The expedition captured Nacogdoches in the summer of 1819 but fell apart when confronted by a Spanish army. With help from Milam, Long regrouped his forces near Galveston the following year. By 1821, Milam had broken with Long's new expedition. While Long marched to Presidio La Bahía, Milam and Trespalacios traveled to Veracruz and Mexico City; both parties met a hostile reception and were quickly imprisoned.[2] While in prison, Long was mysteriously shot and killed by a guard, and Milam came to believe that the murder had been arranged by Trespalacios. This incident drove Milam and some of his friends to plot to kill Trespalacios, and when that plot was discovered, Milam was again imprisoned.[2]

Milam and his friends were sent to Mexico City, where they were held until the fall of 1822, when Joel R. Poinsett, U.S. Commissioner of Observation to Mexico, secured their freedom. With the exception of Milam, all were returned to the United States on the sloop-of-war USS John Adams.[2]

By the spring of 1824, Milam had returned to Mexico, which was adopting the new republican form of government established by the 1824 Constitution of Mexico. Trespalacios and Milam reconciled, and Milam was granted Mexican citizenship and commissioned as a colonel in the Mexican Army.[1][2]

Texas Revolution

[edit]

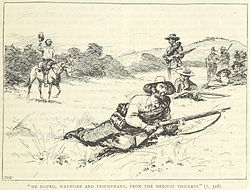

In 1825, Milam and Arthur G. Wavell, an English general in the Mexican Army, became partners in a silver mine operation in Nuevo León. The two also obtained empresario grants in Texas. In 1829, Milam sought to organize a new mining company in partnership with David G. Burnet, but their efforts failed due to a lack of funds. Milam and Wavell's empresarial efforts also failed when their contract was canceled by the Mexican government for an insufficient supply of new citizens for their colony in Texas, following a new law passed in 1830.[2]

In 1835, Milam went to Monclova, the capital of Coahuila y Texas, to urge the new governor, Agustín Viesca, to send a land commissioner to Texas to provide settlers there with land titles. However, before Milam could leave the city, word arrived that Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna had overthrown the representative federal government and established a dictatorship.[1] Governor Viesca fled with Milam, but both were captured and imprisoned at Monterrey. Milam eventually escaped thanks to sympathetic jailers, who also supplied him with a horse.[2]

By chance, Milam encountered a company of Texian soldiers commanded by George Collinsworth, from whom he learned of the movement for independence in Texas. Milam joined them, helping to capture Goliad on October 10, 1835.[2] He wrote: "I assisted Texas to gain her independence. I have endured heat and cold, hunger and thirst; I have borne losses and suffered persecutions; I have been a tenant of every prison between this and Mexico. But the events of this night have compensated me for all my losses and all my sufferings."

Siege of Béxar

[edit]He then joined the main Texian Army in its attempt to expel all Mexican forces from Texas by capturing San Antonio in the ongoing Siege of Béxar. While returning from a scouting mission in the southwest on December 4, 1835, Milam learned that a majority of the army was considering retreating into winter quarters instead of continuing on with the planned attack on San Antonio.[2]

Commander Edward Burleson and his council of officers were reluctant to attack, and the next day at 3 PM, Milam went to Burleson's tent to ask permission to call for volunteers to storm the city. Burleson had little choice but to go along with Milam's plan. Milam was convinced that putting off the final assault on San Antonio would be a disaster for the cause of independence.[2] He then made his famous impassioned plea: "Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?" Three hundred men cheered their support for Milam and volunteered to attack at dawn on December 5.[1][2]

Plans were quickly made for a two-column surprise attack. The volunteers would form at an abandoned mill, Molino Blanco or Zambrano's mill, at 3 AM, while Burleson would hold the rest of the army in reserve. At the same time, Captain James C. Neill would open fire on the Alamo, the center of the Mexican Army's defensive position, with two cannons to distract the Mexican soldiers. Early on December 5, Colonel Milam and Colonel Frank W. Johnson each led a column of attackers into the heavily fortified city, where they eventually seized a foothold and entrenched their position overnight.[citation needed]

On December 7, 1835, the Texians renewed the attack and progressed further into the city, capturing another foothold, but Milam was killed while leading the attack. Standing with Johnson and Henry Karnes near the Veramendi house, Milam had been trying to observe the San Fernando church tower with a field telescope given to him by Stephen F. Austin when he was shot in the head by a Mexican rifleman and killed instantly.[1][2] He fell into the arms of Samuel Maverick. Robert Morris was chosen to take over Milam's command of the first division.[citation needed]

The Mexican Army lost more than 400 killed, deserted, or wounded in the ensuing battle. Texian losses were only 20 to 30 killed. The siege ended on December 9, 1835, when General Martín Perfecto de Cos sent a subordinate to negotiate a truce with the Texians. Morris gave Cos and his troops six days to leave the Alamo. Burleson provided the Mexican Army with as many supplies as he could spare, and the Mexican wounded were allowed to remain behind to be treated by Texian doctors.

Memorials

[edit]

- In 1897, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas placed a marker on Milam's grave site at Milam Park, San Antonio; the marker was moved in 1976 and the location of the grave was forgotten until it was found again in 1993.[2] The statue facing the grave is by Bonnie MacLeary.[3]

- On July 17, 1938, a statue of Milam was unveiled at the Milam County Courthouse in Cameron, Texas.

- Many places in Texas are named for Milam, including the Ben Milam Hotel and Milam Street in Houston and the Milam Building in San Antonio.

References

[edit]- Miller, Edward L. (30 August 2004), New Orleans and the Texas Revolution, Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 1-58544-358-1.

- Nofi, Albert A. (16 February 2001), The Alamo and the Texas War for Independence, Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-81040-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ben Milam Papers #3806, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Garver, Lois. "MILAM, BENJAMIN RUSH". The Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Society. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Best Books on (1940). Texas, a Guide to the Lone Star State. Best Books on. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-1-62376-042-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

Further reading

[edit]- Hall, Franklin (11 May 2023). Who Will Go With Old Ben Milam Into 1930.