Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Copper(II) hydroxide

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Copper(II) hydroxide

| |

| Other names

Cupric hydroxide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.039.817 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Cu(OH)2 | |

| Molar mass | 97.561 g/mol |

| Appearance | Blue or blue-green solid |

| Density | 3.368 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 80 °C (176 °F; 353 K) approximate, decomposes into CuO |

| negligible | |

Solubility product (Ksp)

|

2.20 x 10−20[1] |

| Solubility | insoluble in ethanol; soluble in NH4OH |

| +1170.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

108 J·mol−1·K−1 |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−450 kJ·mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Skin, Eye, & Respiratory Irritant |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

1000 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1 mg/m3 (as Cu)[2] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 1 mg/m3 (as Cu)[2] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

TWA 100 mg/m3 (as Cu)[2] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | SDS |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Copper(II) oxide Copper(II) carbonate Copper(II) sulfate Copper(II) chloride |

Other cations

|

Nickel(II) hydroxide Zinc hydroxide Iron(II) hydroxide Cobalt hydroxide |

Related compounds

|

Copper(I) oxide Copper(I) chloride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Copper(II) hydroxide is the hydroxide of copper with the chemical formula of Cu(OH)2. It is a pale greenish blue or bluish green solid. Some forms of copper(II) hydroxide are sold as "stabilized" copper(II) hydroxide, although they likely consist of a mixture of copper(II) carbonate and hydroxide. Cupric hydroxide is a strong base, although its low solubility in water makes this hard to observe directly.[3]

Occurrence

[edit]Copper(II) hydroxide has been known since copper smelting began around 5000 BC although the alchemists were probably the first to manufacture it by mixing solutions of lye (sodium or potassium hydroxide) and blue vitriol (copper(II) sulfate).[4] Sources of both compounds were available in antiquity.

It was produced on an industrial scale during the 17th and 18th centuries for use in pigments such as blue verditer and Bremen green.[5] These pigments were used in ceramics and painting.[6]

Mineral

[edit]The mineral of the formula Cu(OH)2 is called spertiniite. Copper(II) hydroxide is rarely found as an uncombined mineral because it slowly reacts with carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to form a basic copper(II) carbonate. Thus copper(II) hydroxide slowly acquires a dull green coating in moist air by the reaction:

- 2 Cu(OH)2 + CO2 → Cu2CO3(OH)2 + H2O

The green material is in principle a 1:1 mole mixture of Cu(OH)2 and CuCO3.[7] This patina forms on bronze and other copper alloy statues such as the Statue of Liberty.

Production

[edit]Copper(II) hydroxide can be produced by adding sodium hydroxide to various copper(II) sources. The nature of the resulting copper(II) hydroxide however is sensitive to detailed conditions. Some methods produce granular, robust copper(II) hydroxide while other methods produce a thermally sensitive colloid-like product.[3]

Traditionally a solution of a soluble copper(II) salt, such as copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4·5H2O) is treated with base:[8]

- 2NaOH + CuSO4·5H2O → Cu(OH)2 + 6H2O + Na2SO4

This form of copper hydroxide tends to convert to black copper(II) oxide:[9]

- Cu(OH)2 → CuO + H2O

A purer product can be attained if ammonium chloride is added to the solution beforehand to generate ammonia in situ.[10] Alternatively it can be produced in a two-step procedure from copper(II) sulfate via "basic copper sulfate:"[9]

- 4 CuSO4 + 6 NH3 + 6H2O → Cu4SO4(OH)6 + 3 (NH4)2SO4

- Cu4SO4(OH)6 + 2 NaOH → 4 Cu(OH)2 + Na2SO4

Alternatively, copper hydroxide is readily made by electrolysis of water (containing a little electrolyte such as sodium sulfate or magnesium sulfate) with a copper anode:

- Cu + 2OH− → Cu(OH)2 + 2e−

Structure

[edit]The structure of Cu(OH)2 has been determined by X-ray crystallography. The copper center is square pyramidal. Four Cu-O distances in the plane range are 1.96 Å, and the axial Cu-O distance is 2.36 Å. The hydroxide ligands in the plane are either doubly bridging or triply bridging.[11]

Reactions

[edit]It is stable to about 100 °C.[8] Above this temperature, it will decompose into copper(II) oxide.

Copper(II) hydroxide reacts with a solution of ammonia to form a deep blue solution of tetramminecopper [Cu(NH3)4]2+ complex ion.

Copper(II) hydroxide oxidizes of ammonia in presence of oxygen, giving rise to copper ammine nitrites, such as Cu(NO2)2(NH3)n.[12][13]

Copper(II) hydroxide is mildly amphoteric. It dissolves slightly in concentrated alkali, forming [Cu(OH)4]2−.[14][8]

Reagent for organic chemistry

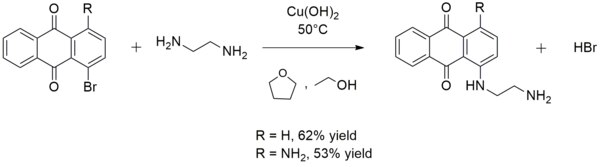

[edit]Copper(II) hydroxide has a specialized role in organic synthesis. Often, when it is utilized for this purpose, it is prepared in situ by mixing a soluble copper(II) salt and potassium hydroxide. It is sometimes used in the synthesis of aryl amines. For example, copper(II) hydroxide catalyzes the reaction of ethylenediamine with 1-bromoanthraquinone or 1-amino-4-bromoanthraquinone to form 1-((2-aminoethyl)amino)anthraquinone or 1-amino-4-((2-aminoethyl)amino)anthraquinone, respectively:[15]

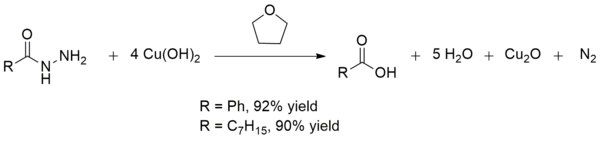

Copper(II) hydroxide also converts acid hydrazides to carboxylic acids at room temperature. This conversion can be used in the synthesis of carboxylic acids in the presence of other fragile functional groups. The yields are generally excellent as is the case with the production of benzoic acid and octanoic acid:[15]

Uses

[edit]Copper(II) hydroxide in ammonia solution, known as Schweizer's reagent, dissolves cellulose.[3] This property led to it being used in the production of rayon, a cellulose fiber.

It is also used in the aquarium industry for its ability to destroy external parasites in fish, including flukes, marine ich, Brooklynellosis, and marine velvet, without killing the fish. Although other water-soluble copper compounds can be effective in this role, they generally result in high fish mortality.

Copper(II) hydroxide has been used as an alternative to the Bordeaux mixture, a fungicide and nematicide.[3][16] Such products include Kocide 3000, produced by Kocide L.L.C. Copper(II) hydroxide is also occasionally used as ceramic colorant.

Copper(II) hydroxide has been combined with latex paint, making a product designed to control root growth in potted plants. Secondary and lateral roots thrive and expand, resulting in a dense and healthy root system. It was sold under the name Spin Out, which was first introduced by Griffin L.L.C. The rights are now owned by SePRO Corp.[17] It is now sold as Microkote either in a solution applied by the end user, or as treated pots.

Other copper(II) hydroxides

[edit]

Together with other components, copper(II) hydroxides are numerous. Several copper(II)-containing minerals contain hydroxide. Notable examples include azurite, malachite, antlerite, and brochantite. Azurite (2CuCO3·Cu(OH)2) and malachite (CuCO3·Cu(OH)2) are hydroxy-carbonates, whereas antlerite (CuSO4·2Cu(OH)2) and brochantite (CuSO4·3Cu(OH)2) are hydroxy-sulfates.

Many synthetic copper(II) hydroxide derivatives have been investigated.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0150". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c d Zhang, Jun; Richardson, H. Wayne (2016). "Copper Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. pp. 1–31. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_567.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Richard Cowen, Essays on Geology, History, and People, Chapter 3: "Fire and Metals: Copper".

- ^ Tony Johansen, Historic Artist's Pigments Archived 2009-06-09 at the Wayback Machine. PaintMaking.com. 2006.

- ^ Blue verditer Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Natural Pigments. 2007.

- ^ Masterson, W. L., & Hurley, C. N. (2004). Chemistry: Principles and Reactions, 5th Ed. Thomson Learning, Inc. (p 331)"

- ^ a b c O. Glemser and H. Sauer "Copper(II) Hydroxide" in Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Press, 1963, NY. Vol. 2. p. 1013.

- ^ a b Solomon, Sally D.; Rutkowsky, Susan A.; Mahon, Megan L.; Halpern, Erica M. (2011). "Synthesis of Copper Pigments, Malachite and Verdigris: Making Tempera Paint". Journal of Chemical Education. 88 (12): 1694–1697. Bibcode:2011JChEd..88.1694S. doi:10.1021/ed200096e.

- ^ Y. Cudennec, A. Lecerf (2003). "The transformation of Cu(OH)2 into CuO, revisited" (PDF). Solid State Sciences. 5 (11–12): 1471–1474. Bibcode:2003SSSci...5.1471C. doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2003.09.009. S2CID 96363475.

- ^ H. R. Oswald; A. Reller; H. W. Schmalle; E. Dubler (1990). "Structure of Copper(II) Hydroxide, Cu(OH)2". Acta Crystallogr. C46 (12): 2279–2284. Bibcode:1990AcCrC..46.2279O. doi:10.1107/S0108270190006230.

- ^ Y. Cudennec; et al. (1995). "Etude cinétique de l'oxydation de l'ammoniac en présence d'ions cuivriques". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIB. 320 (6): 309–316.

- ^ Y. Cudennec; et al. (1993). "Synthesis and study of Cu(NO2)2(NH3)4 and Cu(NO2)2(NH3)2". European Journal of Solid State and Inorganic Chemistry. 30 (1–2): 77–85.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1970). General Chemistry. Dover Publications, Inc. (p 702).

- ^ a b Tsuda, T. (2001). "Copper(II) Hydroxide". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rc228. ISBN 0-471-93623-5.

- ^ Bordeaux Mixture. UC IPM online. 2007.

- ^ "SePRO Corporation" Archived 2009-06-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Zigan, F.; Schuster, H.D. (1972). "Verfeinerung der Struktur von Azurit, Cu3(OH)2(CO3)2, durch Neutronenbeugung". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, Kristallgeometrie, Kristallphysik, Kristallchemie. 135 (5–6): 416–436. Bibcode:1972ZK....135..416Z. doi:10.1524/zkri.1972.135.5-6.416. S2CID 95738208.

- ^ Kondinski, A.; Monakhov, K. (2017). "Breaking the Gordian Knot in the Structural Chemistry of Polyoxometalates: Copper(II)–Oxo/Hydroxo Clusters". Chemistry: A European Journal. 23 (33): 7841–7852. doi:10.1002/chem.201605876. PMID 28083988.

-hidroxid.jpg/250px-Réz(II)-hidroxid.jpg)

-hidroxid.jpg/2000px-Réz(II)-hidroxid.jpg)