Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pigment

View on Wikipedia

A pigment is a chemical compound that gives a substance or organism color, or is used by humans to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly insoluble and chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored substances which are soluble or go into solution at some stage in their use.[1][2] Dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic. Pigments of prehistoric and historic value include ochre, charcoal, and lapis lazuli. Biological pigments are compounds produced by living organisms that provide coloration.

Economic impact

[edit]In 2006, around 7.4 million tons of inorganic, organic, and special pigments were marketed worldwide.[3] According to an April 2018 report by Bloomberg Businessweek, the estimated value of the pigment industry globally is $30 billion. The value of titanium dioxide – used to enhance the white brightness of many products – was placed at $13.2 billion per year, while the color Ferrari red is valued at $300 million each year.[4]

Physical principles

[edit]

Like all materials, the color of pigments arises because they absorb only certain wavelengths of visible light. The bonding properties of the material determine the wavelength and efficiency of light absorption.[5] Light of other wavelengths are reflected or scattered. The reflected light spectrum defines the color that we observe.

The appearance of pigments is sensitive to the source light. Sunlight has a high color temperature and a fairly uniform spectrum. Sunlight is considered a standard for white light. Artificial light sources are less uniform.

Color spaces used to represent colors numerically must specify their light source. Lab color measurements, unless otherwise noted, assume that the measurement was recorded under a D65 light source, or "Daylight 6500 K", which is roughly the color temperature of sunlight.

Other properties of a color, such as its saturation or lightness, may be determined by the other substances that accompany pigments. Binders and fillers can affect the color.

History

[edit]Minerals have been used as colorants since prehistoric times.[6] Early humans used paint for aesthetic purposes such as body decoration. Pigments and paint grinding equipment believed to be between 350,000 and 400,000 years old have been reported in a cave at Twin Rivers, near Lusaka, Zambia. Ochre, iron oxide, was the first color of paint.[7] A favored blue pigment was derived from lapis lazuli. Pigments based on minerals and clays often bear the name of the city or region where they were originally mined. Raw sienna and burnt sienna came from Siena, Italy, while raw umber and burnt umber came from Umbria. These pigments were among the easiest to synthesize, and chemists created modern colors based on the originals. These were more consistent than colors mined from the original ore bodies, but the place names remained. Also found in many Paleolithic and Neolithic cave paintings are Red Ochre, anhydrous Fe2O3, and the hydrated Yellow Ochre (Fe2O3.H2O).[8] Charcoal—or carbon black—has also been used as a black pigment since prehistoric times.[8]

The first known synthetic pigment was Egyptian blue, which is first attested on an alabaster bowl in Egypt dated to Naqada III (circa 3250 BC).[9][10] Egyptian blue (blue frit), calcium copper silicate CaCuSi4O10, made by heating a mixture of quartz sand, lime, a flux and a copper source, such as malachite.[11] Already invented in the Predynastic Period of Egypt, its use became widespread by the 4th Dynasty.[12] It was the blue pigment par excellence of Roman antiquity; its art technological traces vanished in the course of the Middle Ages until its rediscovery in the context of the Egyptian campaign and the excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum.[13] Later premodern synthetic pigments include white lead (basic lead carbonate, (PbCO3)2Pb(OH)2),[14] vermilion, verdigris, and lead-tin yellow. Vermilion, a mercury sulfide, was originally made by grinding a powder of natural cinnabar. From the 17th century on, it was also synthesized from the elements.[15] It was favored by old masters such as Titian. Indian yellow was once produced by collecting the urine of cattle that had been fed only mango leaves.[16] Dutch and Flemish painters of the 17th and 18th centuries favored it for its luminescent qualities, and often used it to represent sunlight.[citation needed] Since mango leaves are nutritionally inadequate for cattle, the practice of harvesting Indian yellow was eventually declared to be inhumane.[16] Modern hues of Indian yellow are made from synthetic pigments. Vermillion has been partially replaced in by cadmium reds.

Because of the cost of lapis lazuli, substitutes were often used. Prussian blue, the oldest modern synthetic pigment, was discovered by accident in 1704.[17] By the early 19th century, synthetic and metallic blue pigments included French ultramarine, a synthetic form of lapis lazuli. Ultramarine was manufactured by treating aluminium silicate with sulfur. Various forms of cobalt blue and Cerulean blue were also introduced. In the early 20th century, Phthalo Blue, a synthetic metallo-organic pigment was prepared. At the same time, Royal Blue, another name once given to tints produced from lapis lazuli, has evolved to signify a much lighter and brighter color, and is usually mixed from Phthalo Blue and titanium dioxide, or from inexpensive synthetic blue dyes.

The discovery in 1856 of mauveine, the first aniline dyes, was a forerunner for the development of hundreds of synthetic dyes and pigments like azo and diazo compounds. These dyes ushered in the flourishing of organic chemistry, including systematic designs of colorants. The development of organic chemistry diminished the dependence on inorganic pigments.[18]

- Paintings illustrating advances in pigments

-

The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1658). Vermeer was lavish in his choice of expensive pigments, including lead-tin yellow, natural ultramarine, and madder lake, as shown in the vibrant painting.[19]

-

Miracle of the Slave by Tintoretto (c. 1548). The son of a master dyer, Tintoretto used Carmine Red Lake pigment, derived from the cochineal insect, to achieve dramatic color effects.

-

Self Portrait by Paul Cézanne. Working in the late 19th century, Cézanne had a much broader palette of colors than his predecessors.

Manufacturing and industrial standards

[edit]

Before the development of synthetic pigments, and the refinement of techniques for extracting mineral pigments, batches of color were often inconsistent. With the development of a modern color industry, manufacturers and professionals have cooperated to create international standards for identifying, producing, measuring, and testing colors.

First published in 1905, the Munsell color system became the foundation for a series of color models, providing objective methods for the measurement of color. The Munsell system describes a color in three dimensions, hue, value (lightness), and chroma (color purity), where chroma is the difference from gray at a given hue and value.

By the middle 20th century, standardized methods for pigment chemistry were available, part of an international movement to create such standards in industry. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) develops technical standards for the manufacture of pigments and dyes. ISO standards define various industrial and chemical properties, and how to test for them. The principal ISO standards that relate to all pigments are as follows:

- ISO-787 General methods of test for pigments and extenders.

- ISO-8780 Methods of dispersion for assessment of dispersion characteristics.

Other ISO standards pertain to particular classes or categories of pigments, based on their chemical composition, such as ultramarine pigments, titanium dioxide, iron oxide pigments, and so forth.

Many manufacturers of paints, inks, textiles, plastics, and colors have voluntarily adopted the Colour Index International (CII) as a standard for identifying the pigments that they use in manufacturing particular colors. First published in 1925—and now published jointly on the web by the Society of Dyers and Colourists (United Kingdom) and the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (US)—this index is recognized internationally as the authoritative reference on colorants. It encompasses more than 27,000 products under more than 13,000 generic color index names.

In the CII schema, each pigment has a generic index number that identifies it chemically, regardless of proprietary and historic names. For example, Phthalocyanine Blue BN has been known by a variety of generic and proprietary names since its discovery in the 1930s. In much of Europe, phthalocyanine blue is better known as Helio Blue, or by a proprietary name such as Winsor Blue. An American paint manufacturer, Grumbacher, registered an alternate spelling (Thanos Blue) as a trademark. Colour Index International resolves all these conflicting historic, generic, and proprietary names so that manufacturers and consumers can identify the pigment (or dye) used in a particular color product. In the CII, all phthalocyanine blue pigments are designated by a generic color index number as either PB15 or PB16, short for pigment blue 15 and pigment blue 16; these two numbers reflect slight variations in molecular structure, which produce a slightly more greenish or reddish blue.

Figures of merit

[edit]The following are some of the attributes of pigments that determine their suitability for particular manufacturing processes and applications:

- Lightfastness and sensitivity for damage from ultraviolet light

- Heat stability

- Toxicity

- Tinting strength

- Staining

- Dispersion (which can be measured with a Hegman gauge)

- Opacity or transparency

- Resistance to alkalis and acids

- Reactions and interactions between pigments

Swatches

[edit]Swatches are used to communicate colors accurately. The types of swatches are dictated by the media, i.e., printing, computers, plastics, and textiles. Generally, the medium that offers the broadest gamut of color shades is widely used across diverse media.

Printed swatches

[edit]Reference standards are provided by printed swatches of color shades. PANTONE, RAL, Munsell, etc. are widely used standards of color communication across diverse media like printing, plastics, and textiles.

Plastic swatches

[edit]Companies manufacturing color masterbatches and pigments for plastics offer plastic swatches in injection molded color chips. These color chips are supplied to the designer or customer to choose and select the color for their specific plastic products.

Plastic swatches are available in various special effects like pearl, metallic, fluorescent, sparkle, mosaic etc. However, these effects are difficult to replicate on other media like print and computer display. Plastic swatches have been created by 3D modelling to including various special effects.

Computer swatches

[edit]The appearance of pigments in natural light is difficult to replicate on a computer display. Approximations are required. The Munsell Color System provides an objective measure of color in three dimensions: hue, value (or lightness), and chroma. Computer displays in general fail to show the true chroma of many pigments, but the hue and lightness can be reproduced with relative accuracy. However, when the gamma of a computer display deviates from the reference value, the hue is also systematically biased.

The following approximations assume a display device at gamma 2.2, using the sRGB color space. The further a display device deviates from these standards, the less accurate these swatches will be.[20] Swatches are based on the average measurements of several lots of single-pigment watercolor paints, converted from Lab color space to sRGB color space for viewing on a computer display. The appearance of a pigment may depend on the brand and even the batch. Furthermore, pigments have inherently complex reflectance spectra that will render their color appearance[21][better source needed] greatly different depending on the spectrum of the source illumination, a property called metamerism. Averaged measurements of pigment samples will only yield approximations of their true appearance under a specific source of illumination. Computer display systems use a technique called chromatic adaptation transforms[22] to emulate the correlated color temperature of illumination sources, and cannot perfectly reproduce the intricate spectral combinations originally seen. In many cases, the perceived color of a pigment falls outside of the gamut of computer displays and a method called gamut mapping is used to approximate the true appearance. Gamut mapping trades off any one of lightness, hue, or saturation accuracy to render the color on screen, depending on the priority chosen in the conversion's ICC rendering intent.

|

#990024

|

PR106 – #E34234

Vermilion (genuine)

|

#FFB02E

|

|---|

|

PB29 – #003BAF

Ultramarine blue

|

PB27 – #0B3E66

|

|---|

Biological pigments

[edit]In biology, a pigment is any colored material of plant or animal cells. Many biological structures, such as skin, eyes, fur, and hair contain pigments (such as melanin). Animal skin coloration often comes about through specialized cells called chromatophores, which animals such as the octopus and chameleon can control to vary the animal's color. Many conditions affect the levels or nature of pigments in plant, animal, some protista, or fungus cells. For instance, the disorder called albinism affects the level of melanin production in animals.

Pigmentation in organisms serves many biological purposes, including camouflage, mimicry, aposematism (warning), sexual selection and other forms of signalling, photosynthesis (in plants), and basic physical purposes such as protection from sunburn.

Pigment color differs from structural color in that pigment color is the same for all viewing angles, whereas structural color is the result of selective reflection or iridescence, usually because of multilayer structures. For example, butterfly wings typically contain structural color, although many butterflies have cells that contain pigment as well.

Pigments by chemical composition

[edit]

- Aluminium pigment: aluminum powder[23]

- Barium: barium white (lithopone)

- Cadmium pigments: cadmium yellow, cadmium red, cadmium green, cadmium orange, cadmium sulfoselenide

- Carbon pigments: carbon black (including vine black, lamp black), ivory black (bone charcoal)

- Chromium pigments: chrome yellow and chrome green (viridian)

- Cobalt pigments: cobalt violet, cobalt blue, cerulean blue, aureolin (cobalt yellow)

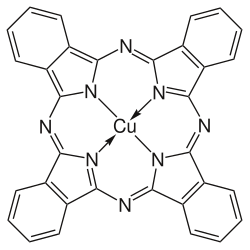

- Copper pigments: azurite, Han purple, Han blue, Egyptian blue, malachite, Paris green, Phthalocyanine Blue BN, Phthalocyanine Green G, verdigris

- Iron oxide pigments: sanguine, caput mortuum, oxide red, red ochre, yellow ochre, Venetian red, Prussian blue, raw sienna, burnt sienna, raw umber, burnt umber

- Lead pigments: lead white, Naples yellow, red lead, lead-tin yellow

- Manganese pigments: manganese violet, YInMn blue, manganese oxide brown or black[24]

- Mercury pigments: vermilion

- Sulfur pigments: ultramarine, ultramarine green shade, lapis lazuli

- Titanium pigments: titanium yellow, titanium white, titanium black

- Zinc pigments: zinc white, zinc ferrite, zinc yellow

Biological and organic

[edit]- Biological origins: alizarin, gamboge, cochineal red, rose madder, indigo, Indian yellow, Tyrian purple

- Non-biological organic: quinacridone, magenta, phthalo green, phthalo blue, pigment red 170, diarylide yellow

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gürses, A.; Açıkyıldız, M.; Güneş, K.; Gürses, M.S. (2016). "Dyes and Pigments: Their Structure and Properties". Dyes and Pigments. SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science. Springer. pp. 13–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33892-7_2. ISBN 978-3-319-33890-3.

Dyes are colored substances which are soluble or go into solution during the application process and impart color by selective absorption of light. Pigments are colored, colorless, or fluorescent particulate organic or inorganic finely divided solids which are usually insoluble in, and essentially chemically unaffected by, the vehicle or medium in which they are incorporated.

- ^ Völz, Hans G.; et al. (2006). "Pigments, Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a20_243.pub2. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ Sahoo, Annapurna; Panigrahi, G. K. (1 September 2016). "A review on Natural Dye: Gift from bacteria" (PDF). International Journal of Bioassays. 5 (9): 4909.

- ^ Schonbrun, Zach (18 April 2018). "The Quest for the Next Billion-Dollar Color". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Thomas B. Brill, Light: Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, Springer 1980, p. 204

- ^ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. pp. 21, 237. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ "Earliest evidence of art found". BBC News. 2 May 2000. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Pigments Through the Ages". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ^ Lorelei H. Corcoran, "The Color Blue as an 'Animator' in Ancient Egyptian Art", in Rachael B.Goldman, (ed.), Essays in Global Color History: Interpreting the Ancient Spectrum (New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2016), pp. 59–82.

- ^ Rossotti, Hazel (1983). Colour: Why the World Isn't Grey. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02386-7.

- ^ Berke, Heinz (2007). "The invention of blue and purple pigments in ancient times". Chemical Society Reviews. 36 (1): 15–30. doi:10.1039/b606268g. PMID 17173142.

- ^ Hatton, G.D.; Shortland, A.J.; Tite, M.S. (2008). "The production technology of Egyptian blue and green frits from second millenium BC Egypt and Mesopotamia". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (6): 1591–1604. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35.1591H. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.008.

- ^ Dariz, Petra; Schmid, Thomas (2021). "Trace compounds in Early Medieval Egyptian blue carry information on provenance, manufacture, application, and ageing". Scientific Reports. 11 (11296): 11296. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1111296D. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90759-6. PMC 8163881. PMID 34050218.

- ^ Lead white Archived 25 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine at ColourLex

- ^ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 146. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ a b "History of Indian yellow". Pigments Through the Ages. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Prussian blue at ColourLex

- ^ Simon Garfield (2000). Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color That Changed the World. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-393-02005-3.

- ^ Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid Archived 14 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, ColourLex

- ^ "Dictionary of Color Terms". Gamma Scientific. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ^ "Color Appearance". Hello Artsy. 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Chromatic Adaptation". cmp.uea.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ Engineer Manual 1110-2-3400 Painting: New Construction and Maintenance (PDF). 30 April 1995. pp. 4–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Hansen, Tony. "Manganese Dioxide". Digital Fire. Archived from the original on 27 September 2025. Retrieved 27 September 2025.

References

[edit]- Ball, Philip (2002). Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-11679-2.

- Doerner, Max (1984). The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting: With Notes on the Techniques of the Old Masters, Revised Edition. Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-657716-X.

- Finlay, Victoria (2003). Color: A Natural History of the Palette. Random House. ISBN 0-8129-7142-6.

- Gage, John (1999). Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22225-3.

- Meyer, Ralph (1991). The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques, Fifth Edition. Viking. ISBN 0-670-83701-6.

- Feller, R. L., ed. (1986). Artists' Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 1. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Roy, A., ed. (1993). Artists' Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2. Oxford University Press.

- Fitzhugh, E. W., ed. (1997). Artists' Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 3. Oxford University Press.

- Berrie, B., ed. (2007). Artists' Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 4. Archetype Books.

External links

[edit]- Pigments through the ages

- ColourLex Pigment Lexicon

- Sarah Lowengard,The Creation of Color in Eighteenth-century Europe, Columbia University Press, 2006

- Alchemy's Rainbow: Pigment Science and the Art of Conservation on YouTube, Chemical Heritage Foundation

- Poisons and Pigments: A Talk with Art Historian Elisabeth Berry-Drago on YouTube, Chemical Heritage Foundation

- The Quest for the Next Billion-Dollar Color

![The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1658). Vermeer was lavish in his choice of expensive pigments, including lead-tin yellow, natural ultramarine, and madder lake, as shown in the vibrant painting.[19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Johannes_Vermeer_-_Het_melkmeisje_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/250px-Johannes_Vermeer_-_Het_melkmeisje_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)