Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

David Nutt

View on Wikipedia

David John Nutt (born 16 April 1951) is an English neuropsychopharmacologist specialising in the research of drugs that affect the brain and conditions such as addiction, anxiety, and sleep.[6] He is the chairman of Drug Science, a non-profit which he founded in 2010 to provide independent, evidence-based information on drugs.[7] In 2019 he co-founded the company GABAlabs and its subsidiary SENTIA Spirits which research and market alternatives to alcohol. Until 2009, he was a professor at the University of Bristol heading their Psychopharmacology Unit.[8] Since then he has been the Edmond J Safra chair in Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and director of the Neuropsychopharmacology Unit in the Division of Brain Sciences there.[9] Nutt was a member of the Committee on Safety of Medicines, and was President of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.[10][11][12]

Key Information

Career summary and research

[edit]Nutt completed his secondary education at Bristol Grammar School and then studied medicine at Downing College, Cambridge, graduating in 1972. In 1975, he completed his clinical training at Guy's Hospital.[13]

He worked as a clinical scientist at the Radcliffe Infirmary from 1978 to 1982 where he carried out basic research into the function of the benzodiazepine receptor/GABA ionophore complex, the long-term effects of BZ agonist treatment and kindling with BZ partial inverse agonists. This work culminated in a ground-breaking paper in Nature in 1982[14] which described the concept of inverse agonism (using his preferred term, "contragonism") for the first time. From 1983 to 1985, he lectured in psychiatry at the University of Oxford. In 1986, he was the Fogarty visiting scientist at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in Bethesda, MD, outside Washington, D.C. Returning to the UK in 1988, he joined the University of Bristol as director of the Psychopharmacology Unit. In 2009, he then established the Department of Neuropsychopharmacology and Molecular Imaging at Imperial College, London, taking a new chair endowed by the Edmond J Safra Philanthropic Foundation.[13] He is an editor of the Journal of Psychopharmacology,[15] and in 2014 was elected president of the European Brain Council.[16]

In 2007 Nutt published a study on the harms of drug use in The Lancet.[17] Eventually, this led to his dismissal from his position in the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD; see government positions below). Subsequently, Nutt and a number of his colleagues who had resigned from the ACMD founded the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, later renamed as Drug Science.[18]

Nutt has since produced numerous prominent reports on drug policy through Drug Science, while launching campaigns of support for evidence-based drug policy; including Project Twenty21, Medical Cannabis Working Group, and the Medical Psychedelics Working Group.[7] In 2013, Drug Science launched a peer-reviewed journal - Journal of Drug Science, Policy and Law - for which Nutt was appointed Editor.[19] Nutt also hosts the Drug Science Podcast, in which he engages drug policy experts, policy-makers, and scientists on the topics of drugs and drug policy.[20]

Nutt is the deputy head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London.[21] He and his team have published research into psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, as well as neuroimaging studies investigating psilocybin, MDMA, LSD, and DMT.[22]

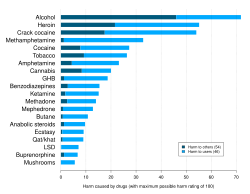

In November 2010, Nutt published a study in The Lancet - co-authored with Les King and Lawrence Phillips, on behalf of the Independent Committee on Drug Science - which ranked the harm done to individual users and broader society by a range of licit and illicit drugs.[23] Owing in part to criticism of the 2007 study for arbitrary weighting of factors,[18][24] the 2010 study employed a multiple-criteria decision analysis in its procedure to support their conclusion that alcohol is more harmful to society than heroin and crack (cocaine), whereas heroin, crack, and methamphetamine are most harmful to individuals.[23] Nutt has also published popular-level articles on these findings in newspapers and print media for the general public,[25] which have been met with to public disagreement from other researchers.[26]

Nutt continues to campaign for changing UK drug laws to facilitate greater research opportunities.[27][28][29][30]

Alcarelle and GABA Labs

[edit]Building on his extensive research on the role of GABA in the brain, and the psychopharmacology of alcohol, since 2014 Nutt has spoken publicly about his desire to bringing-to-market a compound which could act as a "safer" replacement to alcohol and mimic some of its effects – namely, "conviviality" – by affecting the GABA receptor[31] without the negative health impacts of alcohol. Nutt has named the compound "Alcarelle", but has not yet disclosed the exact chemical composition; preliminary tests employed a benzodiazepine derivative, with later adaptations aimed at improving efficacy and reducing abuse potential.

In 2018 Nutt's company GABALabs (previously called "Alcarelle") lodged patents branded as "Alcarelle," [32] for several new compounds proposing to more closely mimic the desired "conviviality" of alcohol.[33][34] As of October 2019, no research has been published regarding the efficacy, safety, or long-term health impacts of these compounds, nor have they been made publicly available to consumers.

In January 2021, the science team at GABA Labs released-to-market a plant-based functional alcohol alternative, under the brand "Sentia,"[35] and advertised as a "botanical spirit" reported to reproduce the relaxed and social effects typically associated with the consumption of alcoholic beverages.[36]

Psychedelics

[edit]

In collaboration with Amanda Feilding and the Beckley Foundation, Nutt is investigating the effects of psychedelics on cerebral blood flow.[38][39][40][41][42]

Government positions

[edit]Nutt previously worked as an advisor to the Ministry of Defence, Department of Health, and the Home Office.[13]

He served on the Committee on Safety of Medicines where he participated in an inquiry into the use of SSRI anti-depressants in 2003. The inquiry drew criticism for Nutt's participation, based on potential conflict-of-interest over his financial involvement in GlaxoSmithKline, which led to his withdrawal from discussions of the drug paroxetine.[43] In January 2008 he was appointed as chairman of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), having previously served as Chair of the Technical Committee of the ACMD for seven years.[6]

"Equasy"

[edit]

As ACMD chairman, government ministers have repeatedly clashed with Nutt over conflicting opinions regarding drug harm and drug classification. In January 2009, Nutt published an editorial in the Journal of Psychopharmacology ("Equasy – An overlooked addiction with implications for the current debate on drug harms") in which the risks associated with horse riding (1 serious adverse event every ~350 exposures) were compared to those of taking ecstasy (1 serious adverse event every ~10,000 exposures).[4]

The word equasy is a portmanteau of ecstasy and equestrianism (based on Latin equus, 'horse'). Nutt told The Daily Telegraph that his intention was "to get people to understand that drug harm can be equal to harms in other parts of life".[45] In 2012, he explained to the UK Home Affairs Committee that he chose riding as the "pseudo-drug" in his comparison after being consulted by a patient with irreversible brain damage caused by a fall from a horse. He discovered that riding was "considerably more dangerous than [he] had thought ... popular but dangerous" and "something ... that young people do".[46]

Equasy has been frequently referred to in later discussions of drug harmfulness and drug policies.[47][48][49][50][51]

The issue of the mismatch between lawmakers' classification of recreational drugs, in particular that of cannabis, and scientific measures of their harmfulness surfaced again in October 2009, after the publication of a pamphlet[52] containing a lecture Nutt had given to the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies at King's College London in July 2009. In this, Nutt repeated his view that illicit drugs should be classified according to the actual evidence of the harm they cause, and presented an analysis in which nine 'parameters of harm' (grouped as 'physical harm', 'dependence', and 'social harms') revealed that alcohol or tobacco were more harmful than LSD, ecstasy or cannabis. In this ranking, alcohol came fifth behind heroin, cocaine, barbiturates and methadone, and tobacco ranked ninth, ahead of cannabis, LSD and ecstasy, he said. In this classification, alcohol and tobacco appeared as Class B drugs, and cannabis was placed at the top of Class C. Nutt also argued that taking cannabis created only a "relatively small risk" of psychotic illness,[53] and that "the obscenity of hunting down low-level cannabis users to protect them is beyond absurd".[54] Nutt objected to the recent re-upgrading (after 5 years) of cannabis from a Class C drug back to a Class B drug (and thus again on a par with amphetamines), considering it politically motivated rather than scientifically justified.[44] In October 2009 Nutt had a public disagreement with psychiatrist Robin Murray in the pages of The Guardian about the dangers of cannabis in triggering psychosis.[26]

Dismissal

[edit]Following the release of this pamphlet, Nutt was dismissed from his ACMD position by the Home Secretary, Alan Johnson. Explaining his dismissal of Nutt, Johnson wrote in a letter to The Guardian that "[Nutt] was asked to go because he cannot be both a government adviser and a campaigner against government policy. [...] As for his comments about horse riding being more dangerous than ecstasy, which you quote with such reverence, it is of course a political rather than a scientific point."[55] Responding in The Times, Professor Nutt said: "I gave a lecture on the assessment of drug harms and how these relate to the legislation controlling drugs. According to Alan Johnson, the Home Secretary, some contents of this lecture meant I had crossed the line from science to policy and so he sacked me. I do not know which comments were beyond the line or, indeed, where the line was [...]".[56] He maintains that "the ACMD was supposed to give advice on policy".[57]

In the wake of Nutt's dismissal, Dr Les King, a part-time advisor to the Department of Health, and the senior chemist on the ACMD, resigned from the body.[58] His resignation was soon followed by that of Marion Walker, Clinical Director of Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust's substance misuse service, and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society's representative on the ACMD.[59]

The Guardian revealed that Alan Johnson ordered what was described as a 'snap review' of the 40-strong ACMD in October 2009. This, it was said, would assess whether the body is "discharging the functions" that it was set up to deliver and decide if it still represented value for money for the public. The review was to be conducted by David Omand.[60] Within hours of that announcement, an article was published online by The Times arguing that Nutt's controversial lecture actually conformed to government guidelines throughout.[61] This issue was further publicised a week later when Liberal Democrat science spokesman Dr Evan Harris, MP, attacked the Home Secretary for apparently having misled Parliament and the country in his original statement about Nutt's dismissal.[62]

John Beddington, the Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Government stated that he agreed with the views of Professor Nutt on cannabis. When asked if he agreed whether cannabis was less harmful than cigarettes and alcohol, he replied: "I think the scientific evidence is absolutely clear cut. I would agree with it."[63] A few days later, it was revealed that a leaked email from the government's Science Minister Lord Drayson was quoted as saying Mr Johnson's decision to dismiss Nutt without consulting him was a "big mistake" that left him "pretty appalled".[64]

On 4 November, the BBC reported that Nutt had financial backing to create a new independent drug research body if the ACMD was disbanded or proved incapable of functioning.[65] This new body, the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs (later renamed DrugScience), was launched in January 2010 (later on to establish, in 2013, the journal Drug Science, Policy and Law). On 10 November 2009, after a meeting between ACMD and Alan Johnson, three other scientists tendered their resignations, Dr Simon Campbell, a chemist, psychologist Dr John Marsden and scientific consultant Ian Ragan.[66]

In an 11 November 2009 editorial in The Lancet, Nutt explicitly attributed his dismissal to a conflict between government and science, and reiterated that "I have repeatedly stated [cannabis] is not safe, but that the idea that you can reduce use through raising the classification in the Misuse of Drugs Act from class C to class B—where it had previously been placed, but thus now increasing the maximum penalty for possession for personal use to 5 years in prison—is implausible."[67] In a rejoinder, William Cullerne Bown of Research Fortnight pointed out that the framing of science vs. government was misleading because the weighting of the factors in Nutt's 2007 Lancet paper was arbitrary, and consequently that there was no scientific answer to ranking drugs.[68] In reply, Nutt admitted the limitations of the original study, and wrote that ACMD was in the process of devising a multicriteria decision-making approach when he was dismissed. Nutt reiterated that "The repeated claims by Gordon Brown's government that it had scientific evidence that trumped that of the ACMD and the acknowledgment that it was only interested in scientific evidence that supported its political aims was a cynical misuse of scientific evidence that breached the principles of the 1971 Act and was insulting to Council." Nutt announced that he and number of colleagues that had resigned from the ACMD had set up an Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs.[18]

A subsequent review of policy drafted by Lord Drayson[18] essentially reaffirmed that the scientific advisers to the government can be dismissed under similar circumstances: "Government and its scientific advisers should not act to undermine mutual trust."[69] This clause was kept despite protest from Sense about Science, Campaign for Science and Engineering, and Liberal Democrat MP Evan Harris; according to Lord Drayson, the clause was requested by John Beddington, the Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK Government.[70] Leslie Iversen was announced as the successor of Nutt as the chair of the ACMD in January 2010.[71]

Honours

[edit]David Nutt is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Academy of Medical Sciences. He holds visiting professorships in Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands. He is a past president of the British Association of Psychopharmacology and of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.[13] He was the recipient of the 2013 John Maddox Prize for promoting sound science and evidence on a matter of public interest, whilst facing difficulty or hostility in doing so.[72] He is past president of the British Neuroscience Association and past president of the European Brain Council.[73]

His book Drugs Without the Hot Air (UIT press) won the Salon London Transmission Prize in 2014.[74]

The University of Bath awarded Nutt with an honorary doctorate of laws in December 2019.[75]

Personal life

[edit]David Nutt lives in Bristol, with his wife Diana. He has four children.[76]

Nutt is a Patron of My Death My Decision, an organisation which seeks a more compassionate approach to dying in the UK, including the legal right to a medically assisted death, if that is a person's persistent wish.[77]

Publications

[edit]Articles

[edit]- Carhart-Harris, RL; et al. (2016). "Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging". PNAS. 113 (17): 4853–4858. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.4853C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1518377113. PMC 4855588. PMID 27071089.

- Nutt, David; Baldwin, David; Aitchison, Katherine (2013). "Benzodiazepines: Risks and benefits. A reconsideration" (PDF). J Psychopharmacol. 27 (11): 967–71. doi:10.1177/0269881113503509. PMID 24067791. S2CID 8040368. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2015.

- Amsterdam, Jan; Nutt, David; Brink, Wim (2013). "Generic legislation of new psychoactive drugs" (PDF). J Psychopharmacol. 27 (3): 317–324. doi:10.1177/0269881112474525. PMID 23343598. S2CID 12288500.

- Carhart-Harris, RL; Erritzoe, D; Williams, T; Stone, JM; Reed, LJ; Colasanti, A; Tyacke, RJ; Leech, R; Malizia, AL; Murphy, K; Hobden, P; Evans, J; Feilding, A; Wise, RG; Nutt, DJ (February 2012). "Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (6): 2138–43. doi:10.1073/pnas.1119598109. PMC 3277566. PMID 22308440.

- David J Nutt; Harrison PJ; Baldwin DS; Barnes TR; et al. (October 2011). "No psychiatry without psychopharmacology". Br J Psychiatry. 199 (4): 263–5. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.094334. PMID 22187725.

- Nutt, DJ; Lingford-Hughes, A; Chick, J (2012). "Through a glass darkly: can we improve clarity about mechanism and aims of medications in drug and alcohol treatments?". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (2): 199–204. doi:10.1177/0269881111410899. PMID 22287478.

- Nutt J. D.J. (June 2011). "Highlights of the international consensus statement on major depressive disorder". J Clin Psychiatry. 72 (6): e21. doi:10.4088/JCP.9058tx2c. PMID 21733474.

- Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD; Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis" (PDF). Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse" (PDF). Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- Nutt, D (2006). "Alcohol Alternatives: A Goal for Psychopharmacology?". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 20 (3): 318–320. doi:10.1177/0269881106063042. PMID 16574703. S2CID 44290147.

Books

[edit]- David J. Nutt (2012). Drugs Without the Hot Air: Minimising the Harms of Legal and Illegal Drugs. Cambridge: UIT. ISBN 978-1-906860-16-5.

- David J. Nutt (2020). Drink?: The New Science of Alcohol and Your Health. Yellow Kite. ISBN 978-1-529393-23-1.

- David J. Nutt (2021). Nutt Uncut. Waterside Press.

- David J. Nutt (2021). Brain and Mind Made Simple. Waterside Press.

- David J. Nutt (2022). Cannabis (seeing through the smoke): The New Science of Cannabis and Your Health. Yellow Kite.

- David J. Nutt (2023). Psychedelics: The revolutionary drugs that could change your life – a guide from the expert. Yellow Kite. ISBN 978-1-529360-53-0.

Medical and science

[edit]Pharmacotherapy

- David J. Nutt; Roni Shiloh; Stryjer Rafael; Abraham Weizman (2005). Essentials in Clinical Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy, Second Edition. London; New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-39983-8. 1st ed(2001):ISBN 1-84184-092-0.

- David J. Nutt; Roni Shiloh; Rafael Stryjer; Abraham Weizman (2006). Atlas of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy, Second Edition. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-84184-281-3. 1st ed(1999):ISBN 1-85317-630-3.

- David J. Nutt; Adam Doble; Ian L. Martin (2001). Calming the brain: benzodiazepines and related drugs from laboratory to clinic. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-84184-052-9.

- David J. Nutt; Mike Briley (2000). Anxiolytics. Basel etc.: Birkhäuser Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7643-6032-0.

- David J. Nutt; Wallace B. Mendelson (1995). Hypnotics and Anxiolytics. London: Bailliere Tindall. ISBN 978-0-7020-1955-5.

Brain science

- David J. Nutt; Martin Sarter; Richard G. Lister (1995). Benzodiazepine receptor inverse agonists. New York: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 978-0-471-56173-6.

Addiction and associated disorder

- David J. Nutt; Trevor W. Robbins; Barry J. Everitt (2010). The neurobiology of addiction: new vistas. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956215-2.

- David J. Nutt; Noeline Latt; Katherine Conigrave; Jane Marshall; John Saunders (2009). Addiction medicine. Oxford Psychiatry Library. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780199539338.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-953933-8.

- David J. Nutt; George F. Koob; Mustafa al'Absi (2008). Bundle for researchers in Stress and Addiction. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-374868-3.

- David J. Nutt; Trevor W. Robbins; Gerald V. Stimson; Martin Ince; Andrew Jackson (2006). Drugs and the future: brain science, addiction and society. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-370624-9.

Anxiety disorders

- David J. Nutt; James C. Ballenger (2003). Anxiety disorders. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-05938-6.

- David J. Nutt; Eric J.L. Griez; Carlo Faravelli; Joseph Zohar (2001). Anxiety disorders: an introduction to clinical management and research. New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/0470846437. ISBN 978-0-471-97873-2.

- David J. Nutt; Spilios Argyropoulos; Adrian Feeney (2002). Anxiety Disorders Comorbid with Depression: Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-84184-049-9.

- David J. Nutt; Karl Rickels; Dan J. Stein (2002). Generalised Anxiety Disorder: Symptomatology, Pathogenesis and Management. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-84184-131-1.

- David J. Nutt; Spilios Argyropoulos; Sam Forshall (2001). Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Diagnosis, Treatment and Its Relationship to Other Anxiety Disorders, 3rd edition. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-84184-135-9. 1st ed(1998):ISBN 1-85317-659-1

- David J. Nutt; Spilios Argyropoulos; Sean Hood (2000). Clinician's manual on anxiety disorders and comorbid depression. London: Science Press. ISBN 978-1-85873-397-5.

Other disorders

- David J. Nutt; Sidney H. Kennedy; Raymond W. Lam; Michael E. Thase (2007). Treating Depression Effectively: Applying Clinical Guidelines, Second Edition. Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-0-415-43910-7. 1st ed(2004):ISBN 1-84184-328-8.

- David J. Nutt; Caroline Bell; John Potokar (1996). Depression. Anxiety and the Mixed Condition - pocketbook. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-85317-359-2.

- David J. Nutt; Eric J. L. Griez; Carlo Faravelli; Joseph Zohar (2005). Mood disorders: clinical management and research issues. London: J. Wiley. doi:10.1002/0470094281. ISBN 978-0-470-09426-6.

- David J. Nutt; Caroline Bell; Christine Masterson; Clare Short (2001). Mood and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: a psychopharmacological. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-85317-924-2.

- David J. Nutt; James C. Ballenger; Jean Pierre Lépine (1999). Panic Disorder: Clinical Diagnosis, Management and Mechanisms. London: Martin Dunitz. ISBN 978-1-85317-518-3.

- David J. Nutt; Murray B. Stein; Joseph Zohar (2009). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis, Management And Treatment, Second Edition. London: Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-0-415-39571-7. 1st(2000):ISBN 1-85317-926-4.

Sleep and connected disorder

- David J. Nutt; Sue Wilson (2008). Sleep disorders. Oxford Psychiatry Library. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780199234332.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-923433-2.

- David J. Nutt; Jaime M. Monti; S. R. Pandi-Perumal; Barry L. Jacobs (2008). Serotonin and Sleep: Molecular, Functional and Clinical Aspects. Vol. 32. Basel: Birkhäuser. pp. 699–700. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8561-3. ISBN 978-3-7643-8560-6. PMC 2675905.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) (PMC link is a 2-page book review)

References

[edit]- ^ "Drug Science founded". drugscience.org.uk.

- ^ "Johnson 'misled MPs over adviser'". BBC News. 8 November 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Sample, Ian (11 April 2016). "LSD's impact on the brain revealed in groundbreaking images". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ a b Nutt, David (21 January 2009). "Equasy -- an overlooked addiction with implications for the current debate on drug harms". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 23 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1177/0269881108099672. PMID 19158127. S2CID 32034780.

- ^ "David Nutt". The Life Scientific. 18 September 2012. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ a b Science and Technology Select Committee (18 July 2006). Drug classification: making a hash of it? (PDF) (Report). House of Commons. p. Ev 1. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ a b "The Truth About Drugs". drugscience.org.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Professor David Nutt". University of Bristol. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ "Home - Professor David Nutt DM, FRCP, FRCPsych, FSB, FMedSci". www.imperial.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "David J Nutt". The Royal Institution. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ David Nutt publications indexed by Microsoft Academic

- ^ bbc.co.uk David Nutt on The Life Scientific with Jim Al-Khalili, September 2012, BBC Radio 4

- ^ a b c d Lucy Goodchild (8 January 2009). "Addiction, anxiety and Alzheimer's disease tackled by new Chair at Imperial College" (Press release). Imperial College, London.

- ^ Nutt, D. J.; Cowen, P. J.; Little, H. J. (1982). "Unusual interactions of benzodiazepine receptor antagonists". Nature. 295 (5848): 436–438. Bibcode:1982Natur.295..436N. doi:10.1038/295436a0. PMID 6276771. S2CID 779441.

- ^ "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class research journals". SAGE Journals.

- ^ "David Nutt elected president of the European Brain Council | Imperial News | Imperial College London". Imperial News. 22 January 2014.

- ^ a b Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse" (PDF). The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ a b c d Nutt, D. (2010). "Nutt damage – Author's reply". The Lancet. 375 (9716): 724. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60302-9. S2CID 54387485.

- ^ "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class research journals". SAGE Journals. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "The Drug Science Podcast". drugscience.org.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "People". Imperial College London. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "Research". Imperial College London. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ a b Nutt, D. J.; King, L. A.; Phillips, L. D. (2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis" (PDF). The Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Tim Locke (1 November 2010) Alcohol more harmful than crack or heroin: Study. Former government drugs advisor Professor David Nutt produces new measures on the way drugs and alcohol cause harm Archived 10 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, WebMD Health News

- ^ "The best scientific advice on drugs (written by David Nutt)". The Guardian. London. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ a b Robin Murray, A clear danger from cannabis, The Guardian, 29 October 2009 replying to David Nutt The cannabis conundrum, The Guardian, 29 October 2009

- ^ "Medicinal cannabis: time for a comeback?". Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ Nutt, David (1 March 2014). "Mind-altering drugs and research: from presumptive prejudice to a Neuroscientific Enlightenment?: Science & Society series on "Drugs and Science"". EMBO Reports. 15 (3): 208–211. doi:10.1002/embr.201338282. PMC 3989684. PMID 24531723.

- ^ Nutt, DJ; King, LA; Nichols, DE (2013). "Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 (8): 577–85. doi:10.1038/nrn3530. PMID 23756634. S2CID 1956833.

- ^ Nutt, D. J.; King, L. A.; Nichols, D. E. (2013). "New victims of current drug laws". Nat Rev Neurosci. 14 (12): 877. doi:10.1038/nrn3530-c2. PMID 24149187. S2CID 205509004.

- ^ "Could 'alcosynth' provide all the joy of booze – without the dangers?". the Guardian. 26 March 2019.

- ^ Amy Fleming (26 March 2019). "Could 'alcosynth' provide all the joy of booze – without the dangers?". The Guardian.

- ^ Journal 6751, GB1813962.6, Applicant: Alcarelle Holdings Limited Title: Mood enhancing compounds. Date Lodged: 28 August 2018

- ^ Journal 6751, GB1813962.9, Applicant: Alcarelle Holdings Limited Title: Mood enhancing compounds. Date Lodged: 28 August 2018

- ^ "Sentia". world.openfoodfacts.org. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Schuster-Bruce, Catherine. "I tried an alcohol-free, no-hangover drink made by a top professor that claims to make you as relaxed as alcohol does. It hits the spot — but make sure you read the label". Business Insider. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Petri, G.; Expert, P.; Turkheimer, F.; Carhart-Harris, R.; Nutt, D.; Hellyer, P. J.; Vaccarino, F. (6 December 2014). "Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 11 (101) 20140873. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.0873. PMC 4223908. PMID 25401177.

- ^ Carhart-Harris R, Kaelen M, Nutt DJ [2014] How do hallucinogens work on the brain? http://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-27/edition-9/how-do-hallucinogens-work-brain Archived 5 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nutt DJ [2014] A brave new world for psychology? The Psychologist Special issue: http://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-27/edition-9/special-issue-brave-new-world-psychology

- ^ Petri, G; Expert, P; Turkheimer, F; Carhart-Harris, R; Nutt, D; Hellyer, PJ; Vaccarino, F (2014). "Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks". J. R. Soc. Interface. 11 (101) 20140873. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.0873. PMC 4223908. PMID 25401177.

- ^ Muthukumaraswamy S, Carhart-Harris R, Moran R, Brookes M, Williams M, Erritzoe D, Sessa B, Papadopoulos A, Bolstridge M, Singh K, Fielding A, Friston K, Nutt DJ (2013) Broadband cortical desynchronisation underlies the human psychedelic state The Journal of Neuroscience, 18 September 2013 • 33(38):15171–15183

- ^ Hobden P, Evans J, Feilding A, Wise RG, Nutt DJ (2012) Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin PNAS 1-6 10.1073/pnas.1119598109

- ^ Sarah Boseley (17 March 2003). "Drugs inquiry thrown into doubt over members' links with manufacturers". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b Dominic Casciani (30 October 2009). "Profile: Professor David Nutt". BBC.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (9 February 2009). "Home Office's drugs adviser apologises for saying ecstasy is no more dangerous than riding a horse". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009.

- ^ "House of Commons: Oral Evidence Taken Before the Home Affairs Committee - Drugs: Breaking the Cycle - Minutes of Evidence (HC 184-II)". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Chu, Ben (8 November 2015). "Why does someone dying from alcohol poisoning get no media coverage, while an ecstasy-related death does?". The Independent (opinion). Archived from the original on 25 December 2015.

- ^ Ellenberg, J. (2014). "Book Review: 'The Norm Chronicles' by Michael Blastland and David Spiegelhalter". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Baggini, J. (2014). "Sind Drogengesetze moralisch inkonsistent?". Die großen Fragen Ethik (in German). pp. 56–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36371-9_6. ISBN 978-3-642-36370-2.

- ^ Watts, Michael; Jolliffe, Gray (2017). Sanación psicodélica para el siglo XXI (in Spanish). Michael Watts. ISBN 978-1-912317-04-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gøtzsche, P.C. (2015). Deadly Psychiatry and Organised Denial. Art People. ISBN 978-87-7159-624-3.

- ^ "David Nutt's pamphlet 'Estimating drug harms: a risky business?'" (PDF). Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ Jones, Sam; Robert Booth (1 November 2009). "David Nutt's sacking provokes mass revolt against Alan Johnson". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Vuillamy, Ed (24 July 2011). "Richard Nixon's 'war on drugs' began 40 years ago, and the battle is still raging". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Alan (2 November 2009). "Why Professor David Nutt was shown the door". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Nutt, David (2 November 2009). "Penalties for drug use must reflect harm". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Nutt, David: Drugs - without the hot air. UIT Cambridge, 2012. page 4

- ^ "Government drugs adviser resigns". BBC News. 1 November 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ "Second drugs adviser quits post". BBC News. 1 November 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Travis, Alan; Deborah Summers (2 November 2009). "Alan Johnson orders swift review of drugs advice body". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Henderson, Mark (2 November 2009). "David Nutt's controversial lecture conformed to government guidelines". The Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ "Johnson 'misled MPs over adviser'". BBC News. 8 November 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (3 November 2009). "Science chief backs cannabis view". BBC News. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ "Minister 'backs adviser autonomy'". BBC News. 6 November 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ "Nutt vows to set up new drug body". BBC News. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ "Three more drugs advisers resign". BBC News. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ Nutt, D. (2009). "Government vs science over drug and alcohol policy". The Lancet. 374 (9703): 1731–1733. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61956-5. PMID 19910043. S2CID 31723334.

- ^ Bown, W. C. (2010). "Nutt damage". The Lancet. 375 (9716): 723–724. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60301-7. PMID 20189019. S2CID 205957921.

- ^ "Scientific advice to government: principles". GOV.UK. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ Nick Dusic (24 March 2010) Principles of Scientific Advice, Campaign for Science and Engineering

- ^ "Focus on cannabis 'past history'". BBC News. 29 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ David Nutt: John Maddox Prize winner 2013 on YouTube

- ^ "List of Officers". European Brain Council. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "List of Transmission Prize winners". Foyles. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Professor David Nutt: oration". www.bath.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 October 2025.

- ^ Nutt, David (2021). Nutt Uncut. Waterside Press. ISBN 978-1-909976-85-6. OCLC 1249695577.

- ^ "About Us". mydeath-decision.org. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

External links

[edit]- University profile

- David Nutt on Twitter

- David Nutt's blog (previous blog)

- Profile on David Nutt in Science. The dangerous professor. Science, 31 January 2014, 343, 478–81.[1]

- ^ Kupferschmidt, Kai (31 January 2014). "The Dangerous Professor". Science. 343 (6170): 478–481. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..478K. doi:10.1126/science.343.6170.478. PMID 24482461.

David Nutt

View on GrokipediaDavid John Nutt (born 16 April 1951) is a British neuropsychopharmacologist and psychiatrist specializing in the effects of psychoactive substances on the brain and in neuropsychiatric conditions including addiction, anxiety, and sleep disorders.[1][2]

As the Edmond J. Safra Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology and head of the Centre for Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, Nutt has advanced empirical methods for evaluating drug harms through multicriteria decision analyses, notably ranking alcohol as the overall most harmful substance due to its physical harm, dependence potential, and societal costs.[1][3]61462-6/abstract)

His commitment to evidence-based drug classification over political considerations led to his dismissal as chair of the UK's Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs in 2009 by Home Secretary Alan Johnson, after he publicly critiqued government decisions that prioritized perceived risks over scientific data, such as reclassifying cannabis despite evidence of lower harm relative to alcohol or tobacco.[4]60301-7/abstract)

Nutt's work extends to pioneering research on psychedelics for therapeutic applications and advocacy for policy reforms grounded in causal assessments of harm reduction, earning him the 2013 John Maddox Prize for promoting science against opposition.[5][6]