Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

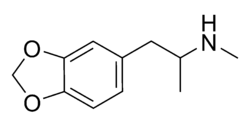

Skeletal structures of (R)-MDMA (top) and (S)-MDMA (bottom) | |

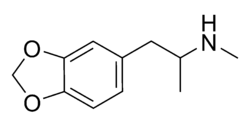

Ball-and-stick models of (R)-MDMA (top) and (S)-MDMA (bottom) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | methylenedioxymethamphetamine: /ˌmɛθɪliːndaɪˈɒksi/ /ˌmɛθæmˈfɛtəmiːn/ |

| Other names | 3,4-MDMA; Ecstasy (E, X, XTC); Midomafetamine; Molly; Mandy;[2][3] Pingers/Pingas[4] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | MDMA |

| Dependence liability | Physical: Not typical[5] Psychological: Moderate[6] |

| Addiction liability | Low–moderate[7][8][9] |

| Routes of administration | Common: By mouth[10] Uncommon: Insufflation,[10] inhalation,[10] injection,[10][11] rectal |

| Drug class | Entactogen; Stimulant; Psychedelic; Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent; Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonist |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: Unknown[13] |

| Protein binding | Unknown[14] |

| Metabolism | Liver, CYP450 extensively involved, including CYP2D6 |

| Metabolites | MDA, HMMA, HMA, HHMA, HHA, THMA, THA, MDP2P, MDOH[15] |

| Onset of action | Oral: 30–45 min[13] |

| Elimination half-life | |

| Duration of action | 3–6 hours[18][8][13] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 193.246 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Density | 1.1 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 105 °C (221 °F) at 0.4 mmHg (experimental) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

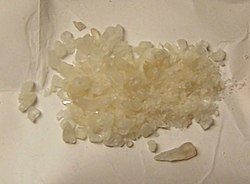

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly known as ecstasy (tablet form), and molly (crystal form),[19][20] is an entactogen with stimulant and minor psychedelic properties.[17][21][22]

MDMA was first synthesized in 1912 by Merck chemist Anton Köllisch.[23] It was used to enhance psychotherapy beginning in the 1970s and became popular as a street drug in the 1980s.[24][25] MDMA is commonly associated with dance parties, raves, and electronic dance music.[26] Tablets sold as ecstasy may be mixed with other substances such as ephedrine, amphetamine, and methamphetamine.[24] In 2016, about 21 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 used ecstasy (0.3% of the world population).[27] In the United States, as of 2017, about 7% of people have used MDMA at some point in their lives and 0.9% have used it in the last year.[28] The lethal risk from one dose of MDMA is estimated to be from 1 death in 20,000 instances to 1 death in 50,000 instances.[29]

The purported pharmacological effects that may be prosocial include altered sensations, increased energy, empathy, and pleasure.[22][24] When taken by mouth, effects begin in 30 to 45 minutes and last three to six hours.[13][25] Short-term adverse effects include grinding of the teeth, blurred vision, sweating, and a rapid heartbeat,[24] and extended use can also lead to addiction, memory problems, paranoia, and difficulty sleeping. Deaths have been reported due to increased body temperature and dehydration. MDMA acts primarily by increasing the release of the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in parts of the brain.[24][25] It belongs to the substituted amphetamine classes of drugs.[10][30] MDMA is structurally similar to mescaline (a psychedelic), methamphetamine (a stimulant), as well as endogenous monoamine neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.[31]

MDMA has limited approved medical uses in a small number of countries,[32] but is illegal in most jurisdictions.[33] MDMA-assisted psychotherapy is a promising and generally safe treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder when administered in controlled therapeutic settings.[34][35] In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given MDMA breakthrough therapy status (though there no current clinical indications in the US).[36] Canada has allowed limited distribution of MDMA upon application to and approval by Health Canada.[37] In Australia, it may be prescribed in the treatment of PTSD by specifically authorised psychiatrists.[38]

Uses

[edit]Recreational

[edit]MDMA is often considered the drug of choice within the rave culture and is also used at clubs, festivals, and house parties.[15] In the rave environment, the sensory effects of music and lighting are often highly synergistic with the drug. The psychedelic amphetamine quality of MDMA offers multiple appealing aspects to users in the rave setting. Some users enjoy the feeling of mass communion from the inhibition-reducing effects of the drug, while others use it as party fuel because of the drug's stimulatory effects.[39] MDMA is used less often than other stimulants, typically less than once per week.[40]

MDMA is sometimes taken in conjunction with other psychoactive drugs such as LSD,[41] psilocybin mushrooms, 2C-B, and ketamine. The combination with LSD is called "candy-flipping".[41] The combination with 2C-B is called "nexus flipping". For this combination, most people take the MDMA first, wait until the peak is over, and then take the 2C-B.[42]

MDMA is often co-administered with alcohol, methamphetamine, and prescription drugs such as SSRIs with which MDMA has several drug-drug interactions.[43][44][45] Three life-threatening reports of MDMA co-administration with ritonavir have been reported;[46] with ritonavir having severe and dangerous drug-drug interactions with a wide range of both psychoactive, anti-psychotic, and non-psychoactive drugs.[47]

Medical

[edit]As of 2023, MDMA therapies have only been approved for research purposes, with no widely accepted medical indications,[10][48][49] although this varies by jurisdiction. Before it was widely banned, it saw limited use in psychotherapy.[8][10][50] In 2017 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted breakthrough therapy designation for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[51][52]

Some researchers have proposed that psychedelics in general may act as active "super placebos" used for therapeutic purposes.[53][54]

Others

[edit]Small doses of MDMA are used by some religious practitioners as an entheogen to enhance prayer or meditation.[55] MDMA has been used as an adjunct to New Age spiritual practices.[56]

Forms

[edit]

MDMA has become widely known as ecstasy (shortened "E", "X", or "XTC"), usually referring to its tablet form, although this term may also include the presence of possible adulterants or diluents. The UK term "mandy" and the US term "molly" colloquially refer to MDMA in a crystalline powder form that is thought to be free of adulterants.[2][3][57] MDMA is also sold in the form of the hydrochloride salt, either as loose crystals or in gelcaps.[58][59] MDMA tablets can sometimes be found in a shaped form that may depict characters from popular culture. These are sometimes collectively referred to as "fun tablets".[60][61]

Partly due to the global supply shortage of sassafras oil—a problem largely assuaged by use of improved or alternative modern methods of synthesis—the purity of substances sold as molly have been found to vary widely. Some of these substances contain methylone, ethylone, MDPV, mephedrone, or any other of the group of compounds commonly known as bath salts, in addition to, or in place of, MDMA.[3][57][58][59] Powdered MDMA ranges from pure MDMA to crushed tablets with 30–40% purity.[10] MDMA tablets typically have low purity due to bulking agents that are added to dilute the drug and increase profits (notably lactose) and binding agents.[10] Tablets sold as ecstasy sometimes contain 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA), other amphetamine derivatives, caffeine, opiates, or painkillers.[8] Some tablets contain little or no MDMA.[8][10][62] The proportion of seized ecstasy tablets with MDMA-like impurities has varied annually and by country.[10] The average content of MDMA in a preparation is 70 to 120 mg with the purity having increased since the 1990s.[8]

MDMA is usually consumed by mouth. It is also sometimes snorted.[24]

Effects

[edit]In general, MDMA users report feeling the onset of subjective effects within 30 to 60 minutes of oral consumption and reaching peak effect at 75 to 120 minutes, which then plateaus for about 3.5 hours.[63] The desired short-term psychoactive effects of MDMA have been reported to include:

- Euphoria – a sense of general well-being and happiness[22][64]

- Increased self-confidence, sociability, and perception of facilitated communication[8][22][64]

- Entactogenic effects—increased empathy or feelings of closeness with others[22][64] and oneself[8]

- Dilated pupils[8]

- Relaxation and reduced anxiety[8]

- Increased emotionality[8]

- A sense of inner peace[64]

- Mild hallucination[64]

- Enhanced sensation, perception, or sexuality[8][22][64]

- Altered sense of time[25]

The experience elicited by MDMA depends on the dose, setting, and user.[8] The variability of the induced altered state is lower compared to other psychedelics. For example, MDMA used at parties is associated with high motor activity, reduced sense of identity, and poor awareness of surroundings. Use of MDMA individually or in small groups in a quiet environment and when concentrating, is associated with increased lucidity, concentration, sensitivity to aesthetic aspects of the environment, enhanced awareness of emotions, and improved capability of communication.[15][65] In psychotherapeutic settings, MDMA effects have been characterized by infantile ideas, mood lability, and memories and moods connected with childhood experiences.[65][66]

MDMA has been described as an "empathogenic" drug because of its empathy-producing effects.[67][68] Results of several studies show the effects of increased empathy with others.[67] When testing MDMA for medium and high doses, it showed increased hedonic and arousal continuum.[69][70] The effect of MDMA increasing sociability is consistent, while its effects on empathy have been more mixed.[71]

Side effects

[edit]Short-term

[edit]Acute adverse effects are usually the result of high or multiple doses, although single dose toxicity can occur in susceptible individuals.[22] The most serious short-term physical health risks of MDMA are hyperthermia and dehydration.[64][72] Cases of life-threatening or fatal hyponatremia (excessively low sodium concentration in the blood) have developed in MDMA users attempting to prevent dehydration by consuming excessive amounts of water without replenishing electrolytes.[64][72][29]

The immediate adverse effects of MDMA use can include:

- Bruxism (grinding and clenching of the teeth)[8][15][22]

- Dehydration[15][64][72]

- Diarrhea[64]

- Erectile dysfunction[8][73]

- Hyperthermia[8][15][72]

- Increased wakefulness or insomnia[8][64]

- Increased perspiration and sweating[64][72]

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure[8][15][72]

- Increased psychomotor activity[8]

- Loss of appetite[8][62]

- Nausea and vomiting[22]

- Visual and auditory hallucinations (rarely)[8]

Other adverse effects that may occur or persist for up to a week following cessation of moderate MDMA use include:[62][22]

- Physiological

- Psychological

Long-term

[edit]As of 2015[update], the long-term effects of MDMA on human brain structure and function have not been fully determined.[76] However, there is consistent evidence of structural and functional deficits in MDMA users with high lifetime exposure.[76] These structural or functional changes appear to be dose dependent and may be less prominent in MDMA users with only a moderate (typically <50 doses used and <100 tablets consumed) lifetime exposure. Nonetheless, moderate MDMA use may still be neurotoxic and what constitutes moderate use is not clearly established.[77]

Furthermore, it is not clear yet whether "typical" recreational users of MDMA (1 to 2 pills of 75 to 125 mg MDMA or analogue every 1 to 4 weeks) will develop neurotoxic brain lesions.[78] Long-term exposure to MDMA in humans has been shown to produce marked neurodegeneration in striatal, hippocampal, prefrontal, and occipital serotonergic axon terminals.[76][79] Neurotoxic damage to serotonergic axon terminals has been shown to persist for more than two years.[79] Elevations in brain temperature from MDMA use are positively correlated with MDMA-induced neurotoxicity.[15][76][77] However, most studies on MDMA and serotonergic neurotoxicity in humans focus more on heavy users who consume as much as seven times or more the amount that most users report taking. The evidence for the presence of serotonergic neurotoxicity in casual users who take lower doses less frequently is not conclusive.[80]

However, adverse neuroplastic changes to brain microvasculature and white matter have been observed to occur in humans using low doses of MDMA.[15][76] Reduced gray matter density in certain brain structures has also been noted in human MDMA users.[15][76] Global reductions in gray matter volume, thinning of the parietal and orbitofrontal cortices, and decreased hippocampal activity have been observed in long term users.[8] The effects established so far for recreational use of ecstasy lie in the range of moderate to severe effects for serotonin transporter reduction.[81]

Impairments in multiple aspects of cognition, including attention, learning, memory, visual processing, and sleep, have been found in regular MDMA users.[8][22][82][76] The magnitude of these impairments is correlated with lifetime MDMA usage[22][82][76] and are partially reversible with abstinence.[8] Several forms of memory are impaired by chronic ecstasy use;[22][82] however, the effects for memory impairments in ecstasy users are generally small overall.[83][84] MDMA use is also associated with increased impulsivity and depression.[8]

Serotonin depletion following MDMA use can cause depression in subsequent days. In some cases, depressive symptoms persist for longer periods.[8] Some studies indicate repeated recreational use of ecstasy is associated with depression and anxiety, even after quitting the drug.[85] Depression is one of the main reasons for cessation of use.[8]

At high doses, MDMA induces a neuroimmune response that, through several mechanisms, increases the permeability of the blood–brain barrier, thereby making the brain more susceptible to environmental toxins and pathogens.[86][87][page needed] In addition, MDMA has immunosuppressive effects in the peripheral nervous system and pro-inflammatory effects in the central nervous system.[88]

MDMA may increase the risk of cardiac valvulopathy in heavy or long-term users due to activation of serotonin 5-HT2B receptors.[89][90] MDMA induces cardiac epigenetic changes in DNA methylation, particularly hypermethylation changes.[91]

Reinforcement disorders

[edit]Approximately 60% of MDMA users experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking MDMA.[62] Some of these symptoms include fatigue, loss of appetite, depression, and trouble concentrating.[62] Tolerance to some of the desired and adverse effects of MDMA is expected to occur with consistent MDMA use.[62] A 2007 delphic analysis of a panel of experts in pharmacology, psychiatry, law, policing and others estimated MDMA to have a psychological dependence and physical dependence potential roughly three-fourths to four-fifths that of cannabis.[92]

MDMA has been shown to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens.[93] Because MDMA releases dopamine in the striatum, the mechanisms by which it induces ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens are analogous to other dopaminergic psychostimulants.[93][94] Therefore, chronic use of MDMA at high doses can result in altered brain structure and drug addiction that occur as a consequence of ΔFosB overexpression in the nucleus accumbens.[94] MDMA is less addictive than other stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine.[95][96] Compared with amphetamine, MDMA and its metabolite MDA are less reinforcing.[97]

One study found approximately 15% of chronic MDMA users met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance dependence.[98] However, there is little evidence for a specific diagnosable MDMA dependence syndrome because MDMA is typically used relatively infrequently.[40]

There are currently no medications to treat MDMA addiction.[99]

During pregnancy

[edit]MDMA is a moderately teratogenic drug (i.e., it is toxic to the fetus).[100][101] In utero exposure to MDMA is associated with a neuro- and cardiotoxicity[101] and impaired motor functioning. Motor delays may be temporary during infancy or long-term. The severity of these developmental delays increases with heavier MDMA use.[82][102] MDMA has been shown to promote the survival of fetal dopaminergic neurons in culture.[103]

Overdose

[edit]MDMA overdose symptoms vary widely due to the involvement of multiple organ systems. Some of the more overt overdose symptoms are listed in the table below. The number of instances of fatal MDMA intoxication is low relative to its usage rates. In most fatalities, MDMA was not the only drug involved. Acute toxicity is mainly caused by serotonin syndrome and sympathomimetic effects.[98] Sympathomimetic side effects can be managed with carvedilol.[104][105] MDMA's toxicity in overdose may be exacerbated by caffeine, with which it is frequently cut in order to increase volume.[106] A scheme for management of acute MDMA toxicity has been published focusing on treatment of hyperthermia, hyponatraemia, serotonin syndrome, and multiple organ failure.[107]

| System | Minor or moderate overdose[108] | Severe overdose[108] |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

| |

| Central nervous system |

||

| Musculoskeletal |

| |

| Respiratory | ||

| Urinary | ||

| Other |

|

Interactions

[edit]A number of drug interactions can occur between MDMA and other drugs, including serotonergic drugs.[62][112] MDMA also interacts with drugs which inhibit CYP450 enzymes, like ritonavir (Norvir), particularly CYP2D6 inhibitors.[62] Life-threatening reactions and death have occurred in people who took MDMA while on ritonavir.[113] Bupropion, a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, has been found to increase MDMA exposure with administration of MDMA.[114][115] Concurrent use of MDMA with certain other serotonergic drugs can result in a life-threatening condition called serotonin syndrome.[8][62] Severe overdose resulting in death has also been reported in people who took MDMA in combination with certain monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs),[8][62] such as phenelzine (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate), or moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix).[116] Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) such as citalopram (Celexa), duloxetine (Cymbalta), fluoxetine (Prozac), and paroxetine (Paxil) have been shown to block most of the subjective effects of MDMA.[117] Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) such as reboxetine (Edronax) have been found to reduce emotional excitation and feelings of stimulation with MDMA but do not appear to influence its entactogenic or mood-elevating effects.[117]

MDMA induces the release of monoamine neurotransmitters and thereby acts as an indirectly acting sympathomimetic and produces a variety of cardiostimulant effects.[114] It dose-dependently increases heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac output.[114][118] SRIs like citalopram and paroxetine, as well as the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin, have been found to partially block the increases in heart rate and blood pressure with MDMA.[114][119] It is notable in this regard that serotonergic psychedelics such as psilocybin, which act as serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists, likewise have sympathomimetic effects.[120][121][122] The NRI reboxetine and the serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) duloxetine block MDMA-induced increases in heart rate and blood pressure.[114] Conversely, bupropion, a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) with only weak dopaminergic activity,[123][124] reduced MDMA-induced heart rate and circulating norepinephrine increases but did not affect MDMA-induced blood pressure increases.[114][115] On the other hand, the robust NDRI methylphenidate, which has sympathomimetic effects of its own, has been found to augment the cardiovascular effects and increases in circulating norepinephrine and epinephrine levels induced by MDMA.[114][125]

The non-selective beta blocker pindolol blocked MDMA-induced increases in heart rate but not blood pressure.[114][104][126] The α2-adrenergic receptor agonist clonidine did not affect the cardiovascular effects of MDMA, though it reduced blood pressure.[114][104][127] The α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists doxazosin and prazosin blocked or reduced MDMA-induced blood pressure increases but augmented MDMA-induced heart rate and cardiac output increases.[114][104][128][118] The dual α1- and β-adrenergic receptor blocker carvedilol reduced MDMA-induced heart rate and blood pressure increases.[114][104][105] In contrast to the cases of serotonergic and noradrenergic agents, the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist haloperidol did not affect the cardiovascular responses to MDMA.[114][129] Due to the theoretical risk of "unopposed α-stimulation" and possible consequences like coronary vasospasm, it has been suggested that dual α1- and β-adrenergic receptor antagonists like carvedilol and labetalol, rather than selective beta blockers, should be used in the management of stimulant-induced sympathomimetic toxicity, for instance in the context of overdose.[104][130]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Target | Affinity (Ki, nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 0.73–13,300 (Ki) 380–2,500 (IC50) 50–72 (EC50) (rat) |

| NET | 27,000–30,500 (Ki) 360–405 (IC50) 54–110 (EC50) (rat) |

| DAT | 6,500–>10,000 (Ki) 1,440–21,000 (IC50) 51–278 (EC50) (rat) |

| 5-HT1A | 6,300–12,200 (Ki) 36,000 nM (EC50) 64% (Emax) |

| 5-HT1B | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1D | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1E | >10,000 |

| 5-HT1F | ND |

| 5-HT2A | 4,600–>10,000 (Ki) 6,100–12,484 (EC50) 40–55% (Emax) |

| 5-HT2B | 500–2,000 (Ki) 2,000–>20,000 (EC50) 32% (Emax) |

| 5-HT2C | 4,400–>13,000 (Ki) 831–9,100 (EC50) 92% (Emax) |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 |

| 5-HT4 | ND |

| 5-HT5A | >10,000 |

| 5-HT6 | >10,000 |

| 5-HT7 | >10,000 |

| α1A | 6,900–>10,000 |

| α1B | >10,000 |

| α1D | ND |

| α2A | 2,532–15,000 |

| α2B | 1,785 |

| α2C | 1,123–1,346 |

| β1, β2 | >10,000 |

| D1 | >13,600 |

| D2 | 25,200 |

| D3 | >17,700 |

| D4 | >10,000 |

| D5 | >10,000 |

| H1 | 2,138–>14,400 |

| H2 | >10,000 |

| H3, H4 | ND |

| M1 | >10,000 |

| M2 | >10,000 |

| M3 | 1,850–>10,000 |

| M4 | 8,250–>10,000 |

| M5 | 6,340–>10,000 |

| nACh | >10,000 |

| TAAR1 | 250–370 (Ki) (rat) 1,000–1,700 (EC50) (rat) 56% (Emax) (rat) 2,400–3,100 (Ki) (mouse) 4,000 (EC50) (mouse) 71% (Emax) (mouse) 35,000 (EC50) (human) 26% (Emax) (human) |

| I1 | 220 |

| σ1, σ2 | ND |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more avidly the drug binds to the site. Proteins are human unless otherwise specified. Refs:[131][132][17][133][134][135] [136][137][138][139][140][141] | |

MDMA is an entactogen or empathogen, as well as a stimulant, euphoriant, and weak psychedelic.[17][142] It is a substrate of the monoamine transporters (MATs) and acts as a monoamine releasing agent (MRA).[17][143][144][145] The drug is specifically a well-balanced serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent (SNDRA).[17][143][144][145] To a lesser extent, MDMA also acts as a serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI).[17][143][144] MDMA enters monoaminergic neurons via the MATs and then, via poorly understood mechanisms, reverses the direction of these transporters to produce efflux of the monoamine neurotransmitters rather than the usual reuptake.[17][146][147][148] Induction of monoamine efflux by amphetamines in general may involve intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ elevation and PKC and CaMKIIα activation.[146][147][148] MDMA also acts on the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) on synaptic vesicles to increase the cytosolic concentrations of the monoamine neurotransmitters available for efflux.[17][143] By inducing release and reuptake inhibition of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, MDMA increases levels of these neurotransmitters in the brain and periphery.[17][143]

In addition to its actions as an SNDRA, MDMA directly but more modestly interacts with a number of monoamine and other receptors.[17][131][132][133][149] It is a low-potency partial agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, including of the serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors.[17][150][151][152][149] The drug also interacts with α2-adrenergic receptors, with the sigma σ1 and σ2 receptors, and with the imidazoline I1 receptor.[17][131][132][133] Along with the preceding receptor interactions, MDMA is a potent partial agonist of the rodent trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1).[139][140] Conversely however, due to species differences, it is far weaker in terms of potency as an agonist of the human TAAR1.[17][139][140][153] Moreover, MDMA appears to act as a weak partial agonist of the human TAAR1 rather than as an efficacious agonist.[139][140] In relation to the preceding findings, MDMA has been said to be essentially inactive as a human TAAR1 agonist.[17] TAAR1 activation is thought to auto-inhibit and constrain the effects of amphetamines that possess TAAR1 agonism, for instance MDMA in rodents.[143][154][155][134][156]

Elevation of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine levels by MDMA is believed to mediate most of the drug's effects, including its entactogenic, stimulant, euphoriant, hyperthermic, and sympathomimetic effects.[17][143][157][71] The entactogenic effects of MDMA, including increased sociability, empathy, feelings of closeness, and reduced aggression, are thought to be mainly due to induction of serotonin release.[71][117][18] The exact serotonin receptors responsible for MDMA's entactogenic effects are unclear, but may include the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor,[158] 5-HT1B receptor,[159] and 5-HT2A receptor,[160] as well as 5-HT1A receptor-mediated oxytocin release and consequent activation of the oxytocin receptor.[17][71][161][162][142] Induction of dopamine release is thought to be importantly involved in the stimulant and euphoriant effects of MDMA,[17][150][163] while induction of norepinephrine release and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor stimulation are believed to mediate its sympathomimetic effects.[114][143] Activation of serotonin 5-HT1B and 5-HT2A receptors is also thought to be involved in the stimulant and euphoriant effects of MDMA, while serotonin 5-HT2C receptor activation is thought to constrain these effects and limit MDMA's reinforcing potential.[164][165][166][167][168][169] Serotonin 5-HT2B receptor signaling appears to be required for MDMA-induced serotonin release and effects.[170][171][172][173][174] MDMA has been associated with a unique subjective "magic" or euphoria that few or no other known entactogens are said to fully reproduce.[175][176] The mechanisms underlying this property of MDMA are unknown, but it has been theorized to be due to a specific mixture and balance of pharmacological activities, including combined serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine release and direct serotonin receptor agonism.[177][175][176][178]

MDMA is often said to have mild or weak psychedelic effects.[179][117][18][180] These effects are said to be dose-dependent, such that greater hallucinogenic effects are produced at higher doses.[179][181] The mild hallucinogenic effects of MDMA include perceptual changes like intensification of visual, auditory, and tactile perception (e.g., brightened colors), a state of dissociation with feelings of depersonalization and derealization (e.g., "oceanic boundlessness"), and thinking disturbances.[179][182][117][180][119][183][181] Conversely, overt hallucinations do not occur, MDMA's hallucinogenic effects are described as "non-problematic" for users, and are said to be less than those of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) or especially those of serotonergic psychedelics like psilocybin.[182][119][18] The hallucinogenic effects of MDMA have been theorized to be mediated by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation analogously to the case of classical psychedelics.[179][119][181][184][182][16] Accordingly, the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin has been reported to reduce MDMA-induced perceptual changes in humans.[179][117][119][181] Conversely however, it failed to affect MDMA-induced feelings of dissociation and oceanic boundlessness.[179][117][181] In contrast, the serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram, which blocks MDMA-induced serotonin release, diminished all of the psychoactive and hallucinogenic effects of MDMA.[179][117][183][119] It has been noted that N-methylation of psychedelic phenethylamines, as in the structural difference between MDA and MDMA, has invariably greatly reduced or abolished their psychedelic activity.[185][186] Whereas MDA and psychedelics like psilocybin induce the head-twitch response in rodents, a behavioral proxy of psychedelic effects, findings on MDMA and the head-twitch response are mixed and conflicting.[187][188][117] In addition, whereas MDA fully substitutes for psychedelics like LSD and DOM in rodent drug discrimination tests, MDMA does not do so, nor do psychedelics generally fully substitute for MDMA.[189][117][190][191]

Long-term repeated activation of serotonin 5-HT2B receptors by MDMA is thought to result in increased risk of organ complications such as valvular heart disease (VHD) and primary pulmonary hypertension (PPH).[192][193][120][194][177][195] MDMA has been associated with serotonergic neurotoxicity.[196][18][197] This may be due to formation of toxic MDMA metabolites and/or induction of simultaneous serotonin and dopamine release, with consequent uptake of dopamine into serotonergic neurons and breakdown into toxic species.[196][18][197] Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonists or serotonergic psychedelics may potentiate the neurotoxicity of MDMA.[198][199][200][201]

MDMA is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, (S)-MDMA and (R)-MDMA.[150][16] (S)-MDMA is much more potent as an SNDRA in vitro and in producing MDMA-like subjective effects in humans than (R)-MDMA.[150][145][16][202] By contrast, (R)-MDMA acts as a lower-potency serotonin–norepinephrine releasing agent (SNRA) with weak or negligible effects on dopamine.[150][145][203] Relatedly, (R)-MDMA shows weak or negligible stimulant-like and rewarding effects in animals.[150][204] Both (S)-MDMA and (R)-MDMA produce entactogen-type effects in animals and humans.[150][16] In addition, both (S)-MDMA and (R)-MDMA are weak agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors.[150][163][16][151][152] (R)-MDMA is more potent and efficacious as a serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptor agonist than (S)-MDMA, whereas (S)-MDMA is somewhat more potent as an agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor.[150][163][16] Due to it being a more potent serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist than (S)-MDMA, (R)-MDMA has been hypothesized to have greater psychedelic effects than (S)-MDMA or racemic MDMA.[205][16] However, this proved not to be the case in a direct clinical comparison of (R)-MDMA, (S)-MDMA, and racemic MDMA, with equivalent hallucinogen-like effects instead found between the three interventions.[205][16]

MDMA produces MDA as a minor active metabolite.[108] Peak levels of MDA are about 5 to 10% of those of MDMA and total exposure to MDA is almost 10% of that of MDMA with oral MDMA administration.[108][193] As a result, MDA may contribute to some extent to the effects of MDMA.[108][184] MDA is an entactogen, stimulant, and weak psychedelic similarly to MDMA.[18] Like MDMA, it acts as a potent and well-balanced SNDRA and as a weak serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonist.[145][151][152] However, MDA shows much more potent and efficacious serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptor agonism than MDMA.[163][184][152][151] Accordingly, MDA produces greater psychedelic effects than MDMA in humans[18] and might particularly contribute to the mild psychedelic-like effects of MDMA.[184] On the other hand, MDA may also be importantly involved in toxicity of MDMA, such as cardiac valvulopathy.[206][193][151]

The duration of action of MDMA (3–6 hours) is much shorter than its elimination half-life (8–9 hours) would imply.[207] In relation to this, MDMA's duration and the offset of its effects appear to be determined more by rapid acute tolerance rather than by circulating drug concentrations.[43] Similar findings have been made for amphetamine and methamphetamine.[208][209][210][211] One mechanism by which tolerance to MDMA may occur is internalization of the serotonin transporter (SERT).[212][213][214][215][216] Although MDMA and serotonin are not significant TAAR1 agonists in humans, TAAR1 activation by MDMA may result in SERT internalization, for instance in rodents in whom MDMA is a potent TAAR1 agonist.[215][216][217][139] It is thought that brain serotonin levels are depleted after MDMA administration but that levels typically return to normal within 24 to 48 hours.[8]

| Compound | Serotonin | Norepinephrine | Dopamine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine | ND | ND | ND |

| (S)-Amphetamine (d) | 698–1,765 | 6.6–7.2 | 5.8–24.8 |

| (R)-Amphetamine (l) | ND | 9.5 | 27.7 |

| Methamphetamine | ND | ND | ND |

| (S)-Methamphetamine (d) | 736–1,292 | 12.3–13.8 | 8.5–24.5 |

| (R)-Methamphetamine (l) | 4,640 | 28.5 | 416 |

| MDA | 160 | 108 | 190 |

| MDMA | 49.6–72 | 54.1–110 | 51.2–278 |

| (S)-MDMA (d) | 74 | 136 | 142 |

| (R)-MDMA (l) | 340 | 560 | 3,700 |

| MDEA | 47 | 2,608 | 622 |

| MBDB | 540 | 3,300 | >100,000 |

| MDAI | 114 | 117 | 1,334 |

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug releases the neurotransmitter. The assays were done in rat brain synaptosomes and human potencies may be different. See also Monoamine releasing agent § Activity profiles for a larger table with more compounds. Refs:[145][151][218][219][220][221][222][223][17] | |||

| Compound | 5-HT2A | 5-HT2B | 5-HT2C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) | Emax | EC50 (nM) | Emax | EC50 (nM) | Emax | |

| Serotonin | 53 | 92% | 1.0 | 100% | 22 | 91% |

| MDA | 1,700 | 57% | 190 | 80% | ND | ND |

| (S)-MDA (d) | 18,200 | 89% | 100 | 81% | 7,400 | 73% |

| (R)-MDA (l) | 5,600 | 95% | 150 | 76% | 7,400 | 76% |

| MDMA | 6,100 | 55% | 2,000–>20,000 | 32% | ND | ND |

| (S)-MDMA (d) | 10,300 | 9% | 6,000 | 38% | 2,600 | 53% |

| (R)-MDMA (l) | 3,100 | 21% | 900 | 27% | 5,400 | 27% |

| Notes: The smaller the Kact or EC50 value, the more strongly the compound produces the effect. Refs:[152][151][224] | ||||||

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Absorption

[edit]The MDMA concentration in the bloodstream starts to rise after about 30 minutes,[225] and reaches its maximal concentration between 1.5 and 3 hours after oral administration.[226] It is then slowly metabolized and excreted, with levels of MDMA and its metabolites decreasing to half their peak concentration over the next several hours.[227] The duration of action of MDMA is about 3 to 6 hours.[18]

Distribution

[edit]The plasma protein binding of MDMA is unknown.[14]

Metabolism

[edit]

Metabolites of MDMA that have been identified in humans include 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxymethamphetamine (HMMA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyamphetamine (HMA), 3,4-dihydroxyamphetamine (DHA) (also called alpha-methyldopamine (α-Me-DA)), 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylacetone (MDP2P), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-hydroxyamphetamine (MDOH). The contributions of these metabolites to the psychoactive and toxic effects of MDMA are an area of active research. 80% of MDMA is metabolised in the liver, and about 20% is excreted unchanged in the urine.[15]

MDMA is known to be metabolized by two main metabolic pathways: (1) O-demethylenation followed by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-catalyzed methylation or glucuronide/sulfate conjugation; and (2) N-dealkylation, deamination, and oxidation to the corresponding benzoic acid derivatives conjugated with glycine.[108] The metabolism may be primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 and COMT. Complex, nonlinear pharmacokinetics arise via autoinhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP2D8, resulting in zeroth order kinetics at higher doses. It is thought that this can result in sustained and higher concentrations of MDMA if the user takes consecutive doses of the drug.[228][non-primary source needed]

Elimination

[edit]MDMA and metabolites are primarily excreted as conjugates, such as sulfates and glucuronides.[229] MDMA is a chiral compound and has been almost exclusively administered as a racemate. However, the two enantiomers have been shown to exhibit different kinetics. The disposition of MDMA may also be stereoselective, with the S-enantiomer having a shorter elimination half-life and greater excretion than the R-enantiomer. Evidence suggests[230] that the area under the blood plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) was two to four times higher for the (R)-enantiomer than the (S)-enantiomer after a 40 mg oral dose in human volunteers. Likewise, the plasma half-life of (R)-MDMA was significantly longer than that of the (S)-enantiomer (5.8 ± 2.2 hours vs 3.6 ± 0.9 hours).[62] However, because MDMA excretion and metabolism have nonlinear kinetics,[231] the half-lives would be higher at more typical doses (100 mg is sometimes considered a typical dose).[226]

Chemistry

[edit]Reactors used to synthesize MDMA on an industrial scale in a clandestine chemical factory in Cikande, Indonesia |

MDMA is in the substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamine and substituted amphetamine classes of chemicals. As a free base, MDMA is a colorless oil insoluble in water.[10] The most common salt of MDMA is the hydrochloride salt;[10] pure MDMA hydrochloride is water-soluble and appears as a white or off-white powder or crystal.[10]

Synthesis

[edit]There are numerous methods available to synthesize MDMA via different intermediates.[232][233][234][235] The original MDMA synthesis described in Merck's patent involves brominating safrole to 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-bromopropane and then reacting this adduct with methylamine.[236][237] Most illicit MDMA is synthesized using MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone) as a precursor. MDP2P in turn is generally synthesized from piperonal, safrole or isosafrole.[238] One method is to isomerize safrole to isosafrole in the presence of a strong base, and then oxidize isosafrole to MDP2P. Another method uses the Wacker process to oxidize safrole directly to the MDP2P intermediate with a palladium catalyst. Once the MDP2P intermediate has been prepared, a reductive amination leads to racemic MDMA (an equal parts mixture of (R)-MDMA and (S)-MDMA).[citation needed] Relatively small quantities of essential oil are required to make large amounts of MDMA. The essential oil of Ocotea cymbarum, for example, typically contains between 80 and 94% safrole. This allows 500 mL of the oil to produce between 150 and 340 grams of MDMA.[239]

Detection in body fluids

[edit]MDMA and MDA may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for use, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a sudden death. Some drug abuse screening programs rely on hair, saliva, or sweat as specimens. Most commercial amphetamine immunoassay screening tests cross-react significantly with MDMA or its major metabolites, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and separately measure each of these substances. The concentrations of MDA in the blood or urine of a person who has taken only MDMA are, in general, less than 10% those of the parent drug.[228][240][241]

History

[edit]Early research and use

[edit]MDMA was first synthesized and patented in 1912 by Merck chemist Anton Köllisch.[242][243] At the time, Merck was interested in developing substances that stopped abnormal bleeding. Merck wanted to avoid an existing patent held by Bayer for one such compound: hydrastinine. Köllisch developed a preparation of a hydrastinine analogue, methylhydrastinine, at the request of fellow lab members, Walther Beckh and Otto Wolfes. MDMA (called methylsafrylamin, safrylmethylamin or N-Methyl-a-Methylhomopiperonylamin in Merck laboratory reports) was an intermediate compound in the synthesis of methylhydrastinine. Merck was not interested in MDMA itself at the time.[243] On 24 December 1912, Merck filed two patent applications that described the synthesis and some chemical properties of MDMA[244] and its subsequent conversion to methylhydrastinine.[245] Merck records indicate its researchers returned to the compound sporadically. A 1920 Merck patent describes a chemical modification to MDMA.[242][246]

MDMA's analogue 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) was first synthesized in 1910 as a derivative of adrenaline.[242] Gordon A. Alles, the discoverer of the psychoactive effects of amphetamine, also discovered the psychoactive effects of MDA in 1930 in a self-experiment in which he administered a high dose (126 mg) to himself.[242][247][248] However, he did not subsequently describe these effects until 1959.[249][247][248] MDA was later tested as an appetite suppressant by Smith, Kline & French and for other uses by other groups in the 1950s.[242] In relation to the preceding, the psychoactive effects of MDA were discovered well before those of MDMA.[242][249]

In 1927, Max Oberlin studied the pharmacology of MDMA while searching for substances with effects similar to adrenaline or ephedrine, the latter being structurally similar to MDMA. Compared to ephedrine, Oberlin observed that it had similar effects on vascular smooth muscle tissue, stronger effects at the uterus, and no "local effect at the eye". MDMA was also found to have effects on blood sugar levels comparable to high doses of ephedrine. Oberlin concluded that the effects of MDMA were not limited to the sympathetic nervous system. Research was stopped "particularly due to a strong price increase of safrylmethylamine", which was still used as an intermediate in methylhydrastinine synthesis. Albert van Schoor performed simple toxicological tests with the drug in 1952, most likely while researching new stimulants or circulatory medications. After pharmacological studies, research on MDMA was not continued. In 1959, Wolfgang Fruhstorfer synthesized MDMA for pharmacological testing while researching stimulants. It is unclear if Fruhstorfer investigated the effects of MDMA in humans.[243]

Outside of Merck, other researchers began to investigate MDMA. In 1953 and 1954, the United States Army commissioned a study of toxicity and behavioral effects in animals injected with mescaline and several analogues, including MDMA. Conducted at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, these investigations were declassified in October 1969 and published in 1973.[250][249] A 1960 Polish paper by Biniecki and Krajewski describing the synthesis of MDMA as an intermediate was the first published scientific paper on the substance.[243][249][251]

MDA appeared as a recreational drug in the mid-1960s.[242] MDMA may have been in non-medical use in the western United States in 1968.[242][252] An August 1970 report at a meeting of crime laboratory chemists indicates MDMA was being used recreationally in the Chicago area by 1970.[249][253] MDMA likely emerged as a substitute for MDA,[254] a drug at the time popular among users of psychedelics[255] which was made a Schedule 1 controlled substance in the United States in 1970.[256][257]

Shulgin's research

[edit]

American chemist and psychopharmacologist Alexander Shulgin reported he synthesized MDMA in 1965 while researching methylenedioxy compounds at Dow Chemical Company, but did not test the psychoactivity of the compound at this time. Around 1970, Shulgin sent instructions for N-methylated MDA (MDMA) synthesis to the founder of a Los Angeles chemical company who had requested them. This individual later provided these instructions to a client in the Midwest. Shulgin may have suspected he played a role in the emergence of MDMA in Chicago.[249]

Shulgin first heard of the psychoactive effects of N-methylated MDA around 1975 from a young student who reported "amphetamine-like content".[249] Around 30 May 1976, Shulgin again heard about the effects of N-methylated MDA,[249] this time from a graduate student in a medicinal chemistry group he advised at San Francisco State University[255][258] who directed him to the University of Michigan study.[259] She and two close friends had consumed 100 mg of MDMA and reported positive emotional experiences.[249] Following the self-trials of a colleague at the University of San Francisco, Shulgin synthesized MDMA and tried it himself in September and October 1976.[249][255] Shulgin first reported on MDMA in a presentation at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland in December 1976.[249] In 1978, he and David E. Nichols published a report on the drug's psychoactive effect in humans.[242] They described MDMA as inducing "an easily controlled altered state of consciousness with emotional and sensual overtones" comparable "to marijuana, to psilocybin devoid of the hallucinatory component, or to low levels of MDA".[260]

While not finding his own experiences with MDMA particularly powerful,[259][261] Shulgin was impressed with the drug's disinhibiting effects and thought it could be useful in therapy.[261] Believing MDMA allowed users to strip away habits and perceive the world clearly, Shulgin called the drug window.[259][262] Shulgin occasionally used MDMA for relaxation, referring to it as "my low-calorie martini", and gave the drug to friends, researchers, and others who he thought could benefit from it.[259] One such person was Leo Zeff, a psychotherapist who had been known to use psychedelic substances in his practice. When he tried the drug in 1977, Zeff was impressed with the effects of MDMA and came out of his semi-retirement to promote its use in therapy. Over the following years, Zeff traveled around the United States and occasionally to Europe, eventually training an estimated four thousand psychotherapists in the therapeutic use of MDMA.[261][263] Zeff named the drug Adam, believing it put users in a state of primordial innocence.[255]

Psychotherapists who used MDMA believed the drug eliminated the typical fear response and increased communication. Sessions were usually held in the home of the patient or the therapist. The role of the therapist was minimized in favor of patient self-discovery accompanied by MDMA induced feelings of empathy. Depression, substance use disorders, relationship problems, premenstrual syndrome, and autism were among several psychiatric disorders MDMA assisted therapy was reported to treat.[257] According to psychiatrist George Greer, therapists who used MDMA in their practice were impressed by the results. Anecdotally, MDMA was said to greatly accelerate therapy.[261] According to David Nutt, MDMA was widely used in the western US in couples counseling, and was called empathy. Only later was the term ecstasy used for it, coinciding with rising opposition to its use.[264][265]

Rising recreational use

[edit]In the late 1970s and early 1980s, "Adam" spread through personal networks of psychotherapists, psychiatrists, users of psychedelics, and yuppies. Hoping MDMA could avoid criminalization like LSD and mescaline, psychotherapists and experimenters attempted to limit the spread of MDMA and information about it while conducting informal research.[257][266] Early MDMA distributors were deterred from large scale operations by the threat of possible legislation.[267] Between the 1970s and the mid-1980s, this network of MDMA users consumed an estimated 500,000 doses.[22][268]

A small recreational market for MDMA developed by the late 1970s,[269] consuming perhaps 10,000 doses in 1976.[256] By the early 1980s MDMA was being used in Boston and New York City nightclubs such as Studio 54 and Paradise Garage.[270][271] Into the early 1980s, as the recreational market slowly expanded, production of MDMA was dominated by a small group of therapeutically minded Boston chemists. Having commenced production in 1976, this "Boston Group" did not keep up with growing demand and shortages frequently occurred.[267]

Perceiving a business opportunity, Michael Clegg, the Southwest distributor for the Boston Group, started his own "Texas Group" backed financially by Texas friends.[267][272] In 1981,[267] Clegg had coined "Ecstasy" as a slang term for MDMA to increase its marketability.[262][266] Starting in 1983,[267] the Texas Group mass-produced MDMA in a Texas lab[266] or imported it from California[262] and marketed tablets using pyramid sales structures and toll-free numbers.[268] MDMA could be purchased via credit card and taxes were paid on sales.[267] Under the brand name "Sassyfras", MDMA tablets were sold in brown bottles.[266] The Texas Group advertised "Ecstasy parties" at bars and discos, describing MDMA as a "fun drug" and "good to dance to".[267] MDMA was openly distributed in Austin and Dallas–Fort Worth area bars and nightclubs, becoming popular with yuppies, college students, and gays.[254][267][268]

Recreational use also increased after several cocaine dealers switched to distributing MDMA following experiences with the drug.[268] A California laboratory that analyzed confidentially submitted drug samples first detected MDMA in 1975. Over the following years the number of MDMA samples increased, eventually exceeding the number of MDA samples in the early 1980s.[273][274] By the mid-1980s, MDMA use had spread to colleges around the United States.[267]: 33

Media attention and scheduling

[edit]United States

[edit]

In an early media report on MDMA published in 1982, a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) spokesman stated the agency would ban the drug if enough evidence for abuse could be found.[267] By mid-1984, MDMA use was becoming more noticed. Bill Mandel reported on "Adam" in a 10 June San Francisco Chronicle article, but misidentified the drug as methyloxymethylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA). In the next month, the World Health Organization identified MDMA as the only substance out of twenty phenethylamines to be seized a significant number of times.[266]

After a year of planning and data collection, MDMA was proposed for scheduling by the DEA on 27 July 1984, with a request for comments and objections.[266][275] The DEA was surprised when a number of psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and researchers objected to the proposed scheduling and requested a hearing.[257] In a Newsweek article published the next year, a DEA pharmacologist stated that the agency had been unaware of its use among psychiatrists.[276] An initial hearing was held on 1 February 1985 at the DEA offices in Washington, D.C., with administrative law judge Francis L. Young presiding.[266] It was decided there to hold three more hearings that year: Los Angeles on 10 June, Kansas City, Missouri on 10–11 July, and Washington, D.C., on 8–11 October.[257][266]

Sensational media attention was given to the proposed criminalization and the reaction of MDMA proponents, effectively advertising the drug.[257] In response to the proposed scheduling, the Texas Group increased production from 1985 estimates of 30,000 tablets a month to as many as 8,000 per day, potentially making two million ecstasy tablets in the months before MDMA was made illegal.[277] By some estimates the Texas Group distributed 500,000 tablets per month in Dallas alone.[262] According to one participant in an ethnographic study, the Texas Group produced more MDMA in eighteen months than all other distribution networks combined across their entire histories.[267] By May 1985, MDMA use was widespread in California, Texas, southern Florida, and the northeastern United States.[252][278] According to the DEA there was evidence of use in twenty-eight states[279] and Canada.[252] Urged by Senator Lloyd Bentsen, the DEA announced an emergency Schedule I classification of MDMA on 31 May 1985. The agency cited increased distribution in Texas, escalating street use, and new evidence of MDA (an analog of MDMA) neurotoxicity as reasons for the emergency measure.[278][280][281] The ban took effect one month later on 1 July 1985[277] in the midst of Nancy Reagan's "Just Say No" campaign.[282][283]

As a result of several expert witnesses testifying that MDMA had an accepted medical usage, the administrative law judge presiding over the hearings recommended that MDMA be classified as a Schedule III substance. Despite this, DEA administrator John C. Lawn overruled and classified the drug as Schedule I.[257][284] Harvard psychiatrist Lester Grinspoon then sued the DEA, claiming that the DEA had ignored the medical uses of MDMA, and the federal court sided with Grinspoon, calling Lawn's argument "strained" and "unpersuasive", and vacated MDMA's Schedule I status.[285] Despite this, less than a month later Lawn reviewed the evidence and reclassified MDMA as Schedule I again, claiming that the expert testimony of several psychiatrists claiming over 200 cases where MDMA had been used in a therapeutic context with positive results could be dismissed because they were not published in medical journals.[257] In 2017, the FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation for its use with psychotherapy for PTSD. However, this designation has been questioned and problematized.[286]

United Nations

[edit]While engaged in scheduling debates in the United States, the DEA also pushed for international scheduling.[277] In 1985, the World Health Organization's Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule I of the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The committee made this recommendation on the basis of the pharmacological similarity of MDMA to previously scheduled drugs, reports of illicit trafficking in Canada, drug seizures in the United States, and lack of well-defined therapeutic use. While intrigued by reports of psychotherapeutic uses for the drug, the committee viewed the studies as lacking appropriate methodological design and encouraged further research. Committee chairman Paul Grof dissented, believing international control was not warranted at the time and a recommendation should await further therapeutic data.[287] The Commission on Narcotic Drugs added MDMA to Schedule I of the convention on 11 February 1986.[288]

Post-scheduling

[edit]

The use of MDMA in Texas clubs declined rapidly after criminalization, but by 1991, the drug became popular among young middle-class whites and in nightclubs.[267] In 1985, MDMA use became associated with acid house on the Spanish island of Ibiza.[267]: 50 [289] Thereafter, in the late 1980s, the drug spread alongside rave culture to the United Kingdom and then to other European and American cities.[267]: 50 Illicit MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later, in high schools. Since the mid-1990s, MDMA has become the most widely used amphetamine-type drug by college students and teenagers.[290]: 1080 MDMA became one of the four most widely used illicit drugs in the US, along with cocaine, heroin, and cannabis.[262] According to some estimates as of 2004, only marijuana attracts more first time users in the United States.[262]

After MDMA was criminalized, most medical use stopped, although some therapists continued to prescribe the drug illegally. Later,[when?] Charles Grob initiated an ascending-dose safety study in healthy volunteers. Subsequent FDA-approved MDMA studies in humans have taken place in the United States in Detroit (Wayne State University), Chicago (University of Chicago), San Francisco (UCSF and California Pacific Medical Center), Baltimore (NIDA–NIH Intramural Program), and South Carolina. Studies have also been conducted in Switzerland (University Hospital of Psychiatry, Zürich), the Netherlands (Maastricht University), and Spain (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona).[291]

"Molly", short for 'molecule', was recognized as a slang term for crystalline or powder MDMA in the 2000s.[292][293]

In 2010, the BBC reported that use of MDMA had decreased in the UK in previous years. This may be due to increased seizures during use and decreased production of the precursor chemicals used to manufacture MDMA. Unwitting substitution with other drugs, such as mephedrone and methamphetamine,[294] as well as legal alternatives to MDMA, such as BZP, MDPV, and methylone, are also thought to have contributed to its decrease in popularity.[295]

In 2017, it was found that some pills being sold as MDMA contained pentylone, which can cause very unpleasant agitation and paranoia.[296]

According to David Nutt, when safrole was restricted by the United Nations in order to reduce the supply of MDMA, producers in China began using anethole instead, but this gives para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA, also known as "Dr Death"), which is much more toxic than MDMA and can cause overheating, muscle spasms, seizures, unconsciousness, and death. People wanting MDMA are sometimes sold PMA instead.[264]

In 2025, the BBC reported on a study of 650 survivors from the Nova music festival massacre. Two-thirds were under the influence of recreational drugs (MDMA, LSD, marijuana or psilocybin) when Hamas attacked the festival on October 7, 2023. MDMA appeared to have a protective effect against later problems with sleeping and emotional distress.[297][298]

Society and culture

[edit]| Substance | Best estimate |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine- type stimulants |

34.16 | 13.42 | 55.24 |

| Cannabis | 192.15 | 165.76 | 234.06 |

| Cocaine | 18.20 | 13.87 | 22.85 |

| Ecstasy | 20.57 | 8.99 | 32.34 |

| Opiates | 19.38 | 13.80 | 26.15 |

| Opioids | 34.26 | 27.01 | 44.54 |

Legal status

[edit]MDMA is legally controlled in most of the world under the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances and other international agreements, although exceptions exist for research and limited medical use. In general, the unlicensed use, sale or manufacture of MDMA are all criminal offences.

Australia

[edit]In Australia, MDMA was rescheduled on 1 July 2023 as a schedule 8 substance (available on prescription) when used in the treatment of PTSD, while remaining a schedule 9 substance (prohibited) for all other uses. For the treatment of PTSD, MDMA can only be prescribed by psychiatrists with specific training and authorisation.[300] In 1986, MDMA was declared an illegal substance because of its allegedly harmful effects and potential for misuse.[301] Any non-authorised sale, use or manufacture is strictly prohibited by law. Permits for research uses on humans must be approved by a recognized ethics committee on human research.

In Western Australia under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1981 4.0g of MDMA is the amount required determining a court of trial, 2.0g is considered a presumption with intent to sell or supply and 28.0g is considered trafficking under Australian law.[302]

The Australian Capital Territory passed legislation to decriminalise the possession of small amounts of MDMA, which took effect in October 2023.[303][304]

Canada

[edit]In Canada, MDMA is listed as a Schedule 1[305] as it is an analogue of amphetamine.[306] The Controlled Drugs and Substances Act was updated as a result of the Safe Streets and Communities Act changing amphetamines from Schedule III to Schedule I in March 2012. In 2022, the federal government granted British Columbia a 3-year exemption, legalizing the possession of up to 2.5 grams (0.088 oz) of MDMA in the province from February 2023 until February 2026.[307][308]

Finland

[edit]Scheduled in the "government decree on substances, preparations and plants considered to be narcotic drugs".[309] Ecstasy is considered a very dangerous illegal drug.[310]

Netherlands

[edit]In 2024, a Dutch state commission issued a report advocating for MDMA to be made available to patients with PTSD.[311]

In June 2011, the Expert Committee on the List (Expertcommissie Lijstensystematiek Opiumwet) issued a report which discussed the evidence for harm and the legal status of MDMA, arguing in favor of maintaining it on List I.[312][313][314]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, MDMA was made illegal in 1977 by a modification order to the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Although MDMA was not named explicitly in this legislation, the order extended the definition of Class A drugs to include various ring-substituted phenethylamines.[315][316] The drug is therefore illegal to sell, buy, or possess without a licence in the UK. Penalties include a maximum of seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or unlimited fine for production or trafficking.

Some researchers such as David Nutt have criticized the scheduling of MDMA, which he determined to be a relatively harmless drug.[317][318] An editorial he wrote in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, where he compared the risk of harm for horse riding (1 adverse event in 350) to that of ecstasy (1 in 10,000) resulted in his dismissal, leading to the resignation of several of his colleagues from the ACMD.[319]

United States

[edit]In the United States, MDMA is listed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.[320] In a 2011 federal court hearing, the American Civil Liberties Union successfully argued that the sentencing guideline for MDMA/ecstasy is based on outdated science, leading to excessive prison sentences.[321] Other courts have upheld the sentencing guidelines. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee explained its ruling by noting that "an individual federal district court judge simply cannot marshal resources akin to those available to the Commission for tackling the manifold issues involved with determining a proper drug equivalency."[312]

Demographics

[edit]

In 2014, 3.5% of 18-to-25-year-olds had used MDMA in the United States.[8] In the European Union as of 2018, 4.1% of adults (15–64 years old) have used MDMA at least once in their life, and 0.8% had used it in the last year.[322] Among young adults, 1.8% had used MDMA in the last year.[322]

In Europe, an estimated 37% of regular club-goers aged 14 to 35 used MDMA in the past year according to the 2015 European Drug report.[8] The highest one-year prevalence of MDMA use in Germany in 2012 was 1.7% among people aged 25 to 29 compared with a population average of 0.4%.[8] Among adolescent users in the United States between 1999 and 2008, girls were more likely to use MDMA than boys.[323]

Economics

[edit]Europe

[edit]In 2008 the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction noted that although there were some reports of tablets being sold for as little as €1, most countries in Europe then reported typical retail prices in the range of €3 to €9 per tablet, typically containing 25–65 mg of MDMA.[324] By 2014 the EMCDDA reported that the range was more usually between €5 and €10 per tablet, typically containing 57–102 mg of MDMA, although MDMA in powder form was becoming more common.[325]

North America

[edit]The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime stated in its 2014 World Drug Report that US ecstasy retail prices range from US$1 to $70 per pill, or from $15,000 to $32,000 per kilogram.[326] A new research area named Drug Intelligence aims to automatically monitor distribution networks based on image processing and machine learning techniques, in which an Ecstasy pill picture is analyzed to detect correlations among different production batches.[327] These novel techniques allow police scientists to facilitate the monitoring of illicit distribution networks.

As of October 2015[update], most of the MDMA in the United States is produced in British Columbia, Canada and imported by Canada-based Asian transnational criminal organizations.[57] The market for MDMA in the United States is relatively small compared to methamphetamine, cocaine, and heroin.[57] In the United States, about 0.9 million people used ecstasy in 2010.[24]

Australia

[edit]MDMA is particularly expensive in Australia, costing A$15–A$30 per tablet. In terms of purity data for Australian MDMA, the average is around 34%, ranging from less than 1% to about 85%. The majority of tablets contain 70–85 mg of MDMA. Most MDMA enters Australia from the Netherlands, the UK, Asia, and the US.[328]

Corporate logos on pills

[edit]A number of ecstasy manufacturers brand their pills with a logo, often that of an unrelated corporation.[329] Some pills depict logos of products or media popular with children, such as Shaun the Sheep.[330]

Research

[edit]MDMA-assisted psychotherapy shows promising efficacy and a generally tolerable safety profile for treating PTSD, with meta-analyses indicating symptom reduction, though careful dosing and controlled therapeutic settings are essential to minimize risks.[34][35]

MDMA is being investigated as a potential treatment for social impairments in autism.[331]

The British critical psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff has critiqued the use and study of MDMA and related drugs like psychedelics for treatment of psychiatric disorders, highlighting concerns including excessive hype around these drugs, blurred lines between medical and recreational use, flawed clinical trial findings, financial conflicts of interest, strong expectancy effects and large placebo responses, short-term benefits over placebo, and their potential for adverse effects, among others.[332]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "FDA Substance Registration System". United States National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ a b Luciano RL, Perazella MA (June 2014). "Nephrotoxic effects of designer drugs: synthetic is not better!". Nature Reviews. Nephrology. 10 (6): 314–324. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2014.44. ISSN 1759-5061. PMID 24662435. S2CID 9817771.

- ^ a b c "DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy or Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Pingers, pingas, pingaz: how drug slang affects the way we use and understand drugs". The Conversation. 8 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

- ^ Palmer RB (2012). Medical toxicology of drug abuse: synthesized chemicals and psychoactive plants. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ Upfal J (2022). Australian Drug Guide: The Plain Language Guide to Drugs and Medicines of All Kinds (9th ed.). Melbourne: Black Inc. p. 319. ISBN 978-1-76064-319-5.

Habit-forming potential moderate. Ecstasy may induce psychological dependence and tolerance to its effect when used frequently.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Betzler F, Viohl L, Romanczuk-Seiferth N (January 2017). "Decision-making in chronic ecstasy users: a systematic review". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 45 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1111/ejn.13480. PMID 27859780. S2CID 31694072.

...the addictive potential of MDMA itself is relatively small.

- ^ Jerome L, Schuster S, Yazar-Klosinski BB (March 2013). "Can MDMA play a role in the treatment of substance abuse?" (PDF). Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 6 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2174/18744737112059990005. PMID 23627786. S2CID 9327169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2020.

Animal and human studies demonstrate moderate abuse liability for MDMA, and this effect may be of most concern to those treating substance abuse disorders.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy')". EMCDDA. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy)". Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheets. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

- ^ Anvisa (24 July 2023). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 25 July 2023). Archived from the original on 27 August 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d Freye E (28 July 2009). "Pharmacological Effects of MDMA in Man". Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Springer Netherlands. pp. 151–160. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2448-0_24. ISBN 978-90-481-2448-0.

- ^ a b "Midomafetamine: Uses, Interactions, Mechanism of Action". DrugBank Online. 31 July 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, et al. (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Archives of Toxicology. 86 (8): 1167–1231. Bibcode:2012ArTox..86.1167C. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347. S2CID 2873101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Straumann I, Avedisian I, Klaiber A, Varghese N, Eckert A, Rudin D, et al. (August 2024). "Acute effects of R-MDMA, S-MDMA, and racemic MDMA in a randomized double-blind cross-over trial in healthy participants". Neuropsychopharmacology. 50 (2): 362–371. doi:10.1038/s41386-024-01972-6. PMC 11631982. PMID 39179638.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Dunlap LE, Andrews AM, Olson DE (October 2018). "Dark Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine" (PDF). ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 9 (10): 2408–2427. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00155. PMC 6197894. PMID 30001118.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Oeri HE (May 2021). "Beyond ecstasy: Alternative entactogens to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine with potential applications in psychotherapy". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 35 (5). Oxford, England: 512–536. doi:10.1177/0269881120920420. PMC 8155739. PMID 32909493.

- ^ Palamar JJ (7 December 2016). "There's something about Molly: The underresearched yet popular powder form of ecstasy in the United States". Substance Abuse. 38 (1): 15–17. doi:10.1080/08897077.2016.1267070. PMC 5578728. PMID 27925866.

- ^ Skaug HA, ed. (14 December 2020). "Hva er tryggest av molly og ecstasy?" [What is safer: molly or ecstasy?]. Ung.no (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

MDMA er virkestoffet i både Molly-krystaller og Ecstasy-tabletter. (MDMA is the active substance in both Molly crystals and Ecstasy tablets)

- ^ Green AR, Mechan AO, Elliott JM, O'Shea E, Colado MI (September 2003). "The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "ecstasy")". Pharmacological Reviews. 55 (3): 463–508. doi:10.1124/pr.55.3.3. PMID 12869661.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Meyer JS (2013). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives". Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 4: 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. PMC 3931692. PMID 24648791.

- ^ Freudenmann RW, Öxler F, Bernschneider-Reif S (August 2006). "The origin of MDMA (ecstasy) revisited: the true story reconstructed from the original documents" (PDF). Addiction. 101 (9). Abingdon, England: 1241–1245. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01511.x. PMID 16911722. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

Although MDMA was, in fact, first synthesized at Merck in 1912, it was not tested pharmacologically because it was only an unimportant precursor in a new synthesis for haemostatic substances.

- ^ a b c d e f g Anderson L, ed. (18 May 2014). "MDMA". Drugs.com. Drugsite Trust. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d "DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. February 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2004). Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. World Health Organization. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-92-4-156235-5. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ World Drug Report 2018 (PDF). United Nations. June 2018. p. 7. ISBN 978-92-1-148304-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g White CM (March 2014). "How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 54 (3): 245–252. doi:10.1002/jcph.266. PMID 24431106. S2CID 6223741.

- ^ Freye E (2009). Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs: A comprehensive review on their mode of action, treatment of abuse and intoxication. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 147. ISBN 978-90-481-2448-0. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Lyles J, Cadet JL (May 2003). "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy) neurotoxicity: cellular and molecular mechanisms". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 42 (2): 155–168. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00173-5. PMID 12738056. S2CID 45330713.

- ^ Philipps D (1 May 2018). "Ecstasy as a Remedy for PTSD? You Probably Have Some Questions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ Patel V (2010). Mental and neurological public health a global perspective (1st ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-12-381527-9. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b Tedesco S, Gajaram G, Chida S, Ahmad A, Pentak M, Kelada M, et al. (May 2021). "The Efficacy of MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Cureus. 13 (5) e15070. doi:10.7759/cureus.15070. PMC 8207489. PMID 34150406.

- ^ a b Smith KW, Sicignano DJ, Hernandez AV, White CM (April 2022). "MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 62 (4): 463–471. doi:10.1002/jcph.1995. PMID 34708874.

- ^ Nuwer R (3 May 2021). "A Psychedelic Drug Passes a Big Test for PTSD Treatment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ "Subsection 56(1) class exemption for practitioners, agents, pharmacists, persons in charge of a hospital, hospital employees, and licensed dealers to conduct activities with psilocybin and MDMA in relation to a special access program authorization". Health Canada. 5 January 2022. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Change to classification of psilocybin and MDMA to enable prescribing by authorised psychiatrists". 3 February 2023. Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Reynolds S (1999). Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-415-92373-6. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ a b McCrady BS, Epstein EE, eds. (2013). Addictions: a comprehensive guidebook (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-19-975366-6. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ a b Zeifman RJ, Kettner H, Pagni BA, Mallard A, Roberts DE, Erritzoe D, et al. (August 2023). "Co-use of MDMA with psilocybin/LSD may buffer against challenging experiences and enhance positive experiences". Scientific Reports. 13 (1) 13645. Bibcode:2023NatSR..1313645Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40856-5. PMC 10444769. PMID 37608057.

- ^ Weiss S (16 February 2024). "Nexus Flipping: What Happens When You Combine MDMA and 2C-B". DoubleBlind Mag. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ a b Hysek CM, Simmler LD, Nicola VG, Vischer N, Donzelli M, Krähenbühl S, et al. (4 May 2012). Laks J (ed.). "Duloxetine inhibits effects of MDMA ("ecstasy") in vitro and in humans in a randomized placebo-controlled laboratory study". PLOS ONE. 7 (5) e36476. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736476H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036476. PMC 3344887. PMID 22574166.

Fig. 7 shows the mean PD effects of MDMA plotted against simultaneous plasma concentrations at the different time points (hysteresis loops). The increases in "any drug effect" (Fig. 7a) and MAP (Fig. 7b) returned to baseline within 6 h when MDMA concentrations were still high. This clockwise hysteresis indicates that a smaller MDMA effect was seen at a given plasma concentration later in time, indicating rapid acute pharmacodynamic tolerance, which was similarly described for cocaine [33]. [...] Figure 7. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) relationship. MDMA effects are plotted against simultaneous MDMA plasma concentrations (a, b). The time of sampling is noted next to each point in minutes or hours after MDMA administration. The clockwise hysteresis indicates acute tolerance to the effects of MDMA.