Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Brain

View on Wikipedia

| Brain | |

|---|---|

Brain of a chimpanzee | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Nervous system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cerebrum |

| Greek | encephalon |

| MeSH | D001921 |

| NeuroNames | 21 |

| TA98 | A14.1.03.001 |

| TA2 | 5415 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for special senses such as vision, hearing, and olfaction. Being the most specialized organ, it is responsible for receiving information from the sensory nervous system, processing that information (thought, cognition, and intelligence) and the coordination of motor control (muscle activity and endocrine system).

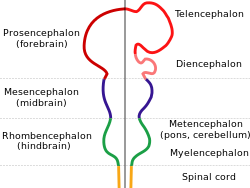

While invertebrate brains arise from paired segmental ganglia (each of which is only responsible for the respective body segment) of the ventral nerve cord, vertebrate brains develop axially from the midline dorsal nerve cord as a vesicular enlargement at the rostral end of the neural tube, with centralized control over all body segments. All vertebrate brains can be embryonically divided into three parts: the forebrain (prosencephalon, subdivided into telencephalon and diencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon) and hindbrain (rhombencephalon, subdivided into metencephalon and myelencephalon). The spinal cord, which directly interacts with somatic functions below the head, can be considered a caudal extension of the myelencephalon enclosed inside the vertebral column. Together, the brain and spinal cord constitute the central nervous system in all vertebrates.

In humans, the cerebral cortex contains approximately 14–16 billion neurons,[1] and the estimated number of neurons in the cerebellum is 55–70 billion.[2] Each neuron is connected by synapses to several thousand other neurons, typically communicating with one another via cytoplasmic processes known as dendrites and axons. Axons are usually myelinated and carry trains of rapid micro-electric signal pulses called action potentials to target specific recipient cells in other areas of the brain or distant parts of the body. The prefrontal cortex, which controls executive functions, is particularly well developed in humans.

Physiologically, brains exert centralized control over a body's other organs. They act on the rest of the body both by generating patterns of muscle activity and by driving the secretion of chemicals called hormones. This centralized control allows rapid and coordinated responses to changes in the environment. Some basic types of responsiveness such as reflexes can be mediated by the spinal cord or peripheral ganglia, but sophisticated purposeful control of behavior based on complex sensory input requires the information-integrating capabilities of a centralized brain.

The operations of individual brain cells are now understood in considerable detail but the way they cooperate in ensembles of millions is yet to be solved.[3] Recent models in modern neuroscience treat the brain as a biological computer, very different in mechanism from a digital computer, but similar in the sense that it acquires information from the surrounding world, stores it, and processes it in a variety of ways.

This article compares the properties of brains across the entire range of animal species, with the greatest attention to vertebrates. It deals with the human brain insofar as it shares the properties of other brains. The ways in which the human brain differs from other brains are covered in the human brain article. Several topics that might be covered here are instead covered there because much more can be said about them in a human context. The most important that are covered in the human brain article are brain disease and the effects of brain damage.

Structure

[edit]

The shape and size of the brain varies greatly between species, and identifying common features is often difficult.[4] Nevertheless, there are a number of principles of brain architecture that apply across a wide range of species.[5] Some aspects of brain structure are common to almost the entire range of animal species;[6] others distinguish "advanced" brains from more primitive ones, or distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates.[4]

The simplest way to gain information about brain anatomy is by visual inspection, but many more sophisticated techniques have been developed. Brain tissue in its natural state is too soft to work with, but it can be hardened by immersion in alcohol or other fixatives, and then sliced apart for examination of the interior. Visually, the interior of the brain consists of areas of so-called grey matter, with a dark color, separated by areas of white matter, with a lighter color. Further information can be gained by staining slices of brain tissue with a variety of chemicals that bring out areas where specific types of molecules are present in high concentrations. It is also possible to examine the microstructure of brain tissue using a microscope, and to trace the pattern of connections from one brain area to another.[7]

Cellular structure

[edit]

The brains of all species are composed primarily of two broad classes of brain cells: neurons and glial cells. Glial cells (also known as glia or neuroglia) come in several types, and perform a number of critical functions, including structural support, metabolic support, insulation, and guidance of development. Neurons, however, are usually considered the most important cells in the brain.[8] In humans, the cerebral cortex contains approximately 14–16 billion neurons,[1] and the estimated number of neurons in the cerebellum is 55–70 billion.[2] Each neuron is connected by synapses to several thousand other neurons. The property that makes neurons unique is their ability to send signals to specific target cells, sometimes over long distances.[8] They send these signals by means of an axon, which is a thin protoplasmic fiber that extends from the cell body and projects, usually with numerous branches, to other areas, sometimes nearby, sometimes in distant parts of the brain or body. The length of an axon can be extraordinary: for example, if a pyramidal cell (an excitatory neuron) of the cerebral cortex were magnified so that its cell body became the size of a human body, its axon, equally magnified, would become a cable a few centimeters in diameter, extending more than a kilometer.[9] These axons transmit signals in the form of electrochemical pulses called action potentials, which last less than a thousandth of a second and travel along the axon at speeds of 1–100 meters per second. Some neurons emit action potentials constantly, at rates of 10–100 per second, usually in irregular patterns; other neurons are quiet most of the time, but occasionally emit a burst of action potentials.[10]

Axons transmit signals to other neurons by means of specialized junctions called synapses. A single axon may make as many as several thousand synaptic connections with other cells.[8] When an action potential, traveling along an axon, arrives at a synapse, it causes a chemical called a neurotransmitter to be released. The neurotransmitter binds to receptor molecules in the membrane of the target cell.[8]

Synapses are the key functional elements of the brain.[11] The essential function of the brain is cell-to-cell communication, and synapses are the points at which communication occurs. The human brain has been estimated to contain approximately 100 trillion synapses;[12] even the brain of a fruit fly contains several million.[13] The functions of these synapses are very diverse: some are excitatory (exciting the target cell); others are inhibitory; others work by activating second messenger systems that change the internal chemistry of their target cells in complex ways.[11] A large number of synapses are dynamically modifiable; that is, they are capable of changing strength in a way that is controlled by the patterns of signals that pass through them. It is widely believed that activity-dependent modification of synapses is the brain's primary mechanism for learning and memory.[11]

Most of the space in the brain is taken up by axons, which are often bundled together in what are called nerve fiber tracts. A myelinated axon is wrapped in a fatty insulating sheath of myelin, which serves to greatly increase the speed of signal propagation. (There are also unmyelinated axons). Myelin is white, making parts of the brain filled exclusively with nerve fibers appear as light-colored white matter, in contrast to the darker-colored grey matter that marks areas with high densities of neuron cell bodies.[8]

Evolution

[edit]Generic bilaterian nervous system

[edit]

Except for a few primitive organisms such as sponges (which have no nervous system)[14] and cnidarians (which have a diffuse nervous system consisting of a nerve net),[14] all living multicellular animals are bilaterians, meaning animals with a bilaterally symmetric body plan (that is, left and right sides that are approximate mirror images of each other).[15] All bilaterians are thought to have descended from a common ancestor that appeared late in the Cryogenian period, 700–650 million years ago, and it has been hypothesized that this common ancestor had the shape of a simple tubeworm with a segmented body.[15] At a schematic level, that basic worm-shape continues to be reflected in the body and nervous system architecture of all modern bilaterians, including vertebrates.[16] The fundamental bilateral body form is a tube with a hollow gut cavity running from the mouth to the anus, and a nerve cord with an enlargement (a ganglion) for each body segment, with an especially large ganglion at the front, called the brain. The brain is small and simple in some species, such as nematode worms; in other species, such as vertebrates, it is a large and very complex organ.[4] Some types of worms, such as leeches, also have an enlarged ganglion at the back end of the nerve cord, known as a "tail brain".[17]

There are a few types of existing bilaterians that lack a recognizable brain, including echinoderms and tunicates. It has not been definitively established whether the existence of these brainless species indicates that the earliest bilaterians lacked a brain, or whether their ancestors evolved in a way that led to the disappearance of a previously existing brain structure.

Invertebrates

[edit]

This category includes tardigrades, arthropods, molluscs, and numerous types of worms. The diversity of invertebrate body plans is matched by an equal diversity in brain structures.[18]

Two groups of invertebrates have notably complex brains: arthropods (insects, crustaceans, arachnids, and others), and cephalopods (octopuses, squids, and similar molluscs).[19] The brains of arthropods and cephalopods arise from twin parallel nerve cords that extend through the body of the animal. Arthropods have a central brain, the supraesophageal ganglion, with three divisions and large optical lobes behind each eye for visual processing.[19] Cephalopods such as the octopus and squid have the largest brains of any invertebrates.[20]

There are several invertebrate species whose brains have been studied intensively because they have properties that make them convenient for experimental work:

- Fruit flies (Drosophila), because of the large array of techniques available for studying their genetics, have been a natural subject for studying the role of genes in brain development.[21] In spite of the large evolutionary distance between insects and mammals, many aspects of Drosophila neurogenetics have been shown to be relevant to humans. The first biological clock genes, for example, were identified by examining Drosophila mutants that showed disrupted daily activity cycles.[22] A search in the genomes of vertebrates revealed a set of analogous genes, which were found to play similar roles in the mouse biological clock—and therefore almost certainly in the human biological clock as well.[23] Studies done on Drosophila, also show that most neuropil regions of the brain are continuously reorganized throughout life in response to specific living conditions.[24]

- The nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, like Drosophila, has been studied largely because of its importance in genetics.[25] In the early 1970s, Sydney Brenner chose it as a model organism for studying the way that genes control development. One of the advantages of working with this worm is that the body plan is very stereotyped: the nervous system of the hermaphrodite contains exactly 302 neurons, always in the same places, making identical synaptic connections in every worm.[26] Brenner's team sliced worms into thousands of ultrathin sections and photographed each one under an electron microscope, then visually matched fibers from section to section, to map out every neuron and synapse in the entire body.[27] The complete neuronal wiring diagram of C.elegans – its connectome was achieved.[28] Nothing approaching this level of detail is available for any other organism, and the information gained has enabled a multitude of studies that would otherwise have not been possible.[29]

- The sea slug Aplysia californica was chosen by Nobel Prize-winning neurophysiologist Eric Kandel as a model for studying the cellular basis of learning and memory, because of the simplicity and accessibility of its nervous system, and it has been examined in hundreds of experiments.[30]

Vertebrates

[edit]

The first vertebrates appeared over 500 million years ago (Mya) during the Cambrian period, and may have resembled the modern jawless fish (hagfish and lamprey) in form.[31] Jawed vertebrates appeared by 445 Mya, tetrapods by 350 Mya, amniotes by 310 Mya and mammaliaforms by 200 Mya (approximately). Each vertebrate clade has an equally long evolutionary history, but the brains of modern fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals show a gradient of size and complexity that roughly follows the evolutionary sequence. All of these brains contain the same set of basic anatomical structures, but many are rudimentary in the hagfish, whereas in mammals the foremost part (forebrain, especially the telencephalon) is greatly developed and expanded.[32]

Brains are most commonly compared in terms of their mass. The relationship between brain size, body size and other variables has been studied across a wide range of vertebrate species. As a rule of thumb, brain size increases with body size, but not in a simple linear proportion. In general, smaller animals tend to have proportionally larger brains, measured as a fraction of body size. For mammals, the relationship between brain volume and body mass essentially follows a power law with an exponent of about 0.75.[33] This formula describes the central tendency, but every family of mammals departs from it to some degree, in a way that reflects in part the complexity of their behavior. For example, primates have brains 5 to 10 times larger than the formula predicts. Predators, who have to implement various hunting strategies against the ever changing anti-predator adaptations, tend to have larger brains relative to body size than their prey.[34]

All vertebrate brains share a common underlying form, which appears most clearly during early stages of embryonic development. In its earliest form, the brain appears as three vesicular swellings at the front end of the neural tube; these swellings eventually become the forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon) and hindbrain (rhombencephalon), respectively. At the earliest stages of brain development, the three areas are roughly equal in size. In many aquatic/semiaquatic vertebrates such as fish and amphibians, the three parts remain similar in size in adults, but in terrestrial tetrapods such as mammals, the forebrain becomes much larger than the other parts, the hindbrain develops a bulky dorsal extension known as the cerebellum, and the midbrain becomes very small as a result.[8]

The brains of vertebrates are made of very soft tissue.[8] Living brain tissue is pinkish on the outside and mostly white on the inside, with subtle variations in color. Vertebrate brains are surrounded by a system of connective tissue membranes called meninges, which separate the skull from the brain. Cerebral arteries pierce the outer two layers of the meninges, the dura and arachnoid mater, into the subarachnoid space and perfuse the brain parenchyma via arterioles perforating into the innermost layer of the meninges, the pia mater. The endothelial cells in the cerebral blood vessel walls are joined tightly to one another, forming the blood–brain barrier, which blocks the passage of many toxins and pathogens[35] (though at the same time blocking antibodies and some drugs, thereby presenting special challenges in treatment of diseases of the brain).[36] As a result of the osmotic restriction by the blood-brain barrier, the metabolites within the brain are cleared mostly by bulk flow of the cerebrospinal fluid within the glymphatic system instead of via venules like other parts of the body.

Neuroanatomists usually divide the vertebrate brain into six main subregions: the telencephalon (the cerebral hemispheres), diencephalon (thalamus and hypothalamus), mesencephalon (midbrain), cerebellum, pons and medulla oblongata, with the midbrain, pons and medulla often collectively called the brainstem. Each of these areas has a complex internal structure. Some parts, such as the cerebral cortex and the cerebellar cortex, are folded into convoluted gyri and sulci in order to maximize surface area within the available intracranial space. Other parts, such as the thalamus and hypothalamus, consist of many small clusters of nuclei known as "ganglia". Thousands of distinguishable areas can be identified within the vertebrate brain based on fine distinctions of neural structure, chemistry, and connectivity.[8]

Although the same basic components are present in all vertebrate brains, some branches of vertebrate evolution have led to substantial distortions of brain geometry, especially in the forebrain area. The brain of a shark shows the basic components in a straightforward way, but in teleost fishes (the great majority of existing fish species), the forebrain has become "everted", like a sock turned inside out. In birds, there are also major changes in forebrain structure.[37] These distortions can make it difficult to match brain components from one species with those of another species.[38]

Here is a list of some of the most important vertebrate brain components, along with a brief description of their functions as currently understood:

- The medulla, along with the spinal cord, contains many small nuclei involved in a wide variety of sensory and involuntary motor functions such as vomiting, heart rate and digestive processes.[8]

- The pons lies in the brainstem directly above the medulla. Among other things, it contains nuclei that control often voluntary but simple acts such as sleep, respiration, swallowing, bladder function, equilibrium, eye movement, facial expressions, and posture.[39]

- The hypothalamus is a small region at the base of the forebrain, whose complexity and importance belies its size. It is composed of numerous small nuclei, each with distinct connections and neurochemistry. The hypothalamus is engaged in additional involuntary or partially voluntary acts such as sleep and wake cycles, eating and drinking, and the release of some hormones.[40]

- The thalamus is a collection of nuclei with diverse functions: some are involved in relaying information to and from the cerebral hemispheres, while others are involved in motivation. The subthalamic area (zona incerta) seems to contain action-generating systems for several types of "consummatory" behaviors such as eating, drinking, defecation, and copulation.[41]

- The cerebellum modulates the outputs of other brain systems, whether motor-related or thought related, to make them certain and precise. Removal of the cerebellum does not prevent an animal from doing anything in particular, but it makes actions hesitant and clumsy. This precision is not built-in but learned by trial and error. The muscle coordination learned while riding a bicycle is an example of a type of neural plasticity that may take place largely within the cerebellum.[8] 10% of the brain's total volume consists of the cerebellum and 50% of all neurons are held within its structure.[42]

- The optic tectum allows actions to be directed toward points in space, most commonly in response to visual input. In mammals, it is usually referred to as the superior colliculus, and its best-studied function is to direct eye movements. It also directs reaching movements and other object-directed actions. It receives strong visual inputs, but also inputs from other senses that are useful in directing actions, such as auditory input in owls and input from the thermosensitive pit organs in snakes. In some primitive fishes, such as lampreys, this region is the largest part of the brain.[43] The superior colliculus is part of the midbrain.

- The pallium is a layer of grey matter that lies on the surface of the forebrain and is the most complex and most recent evolutionary development of the brain as an organ.[44] In reptiles and mammals, it is called the cerebral cortex. Multiple functions involve the pallium, including smell and spatial memory. In mammals, where it becomes so large as to dominate the brain, it takes over functions from many other brain areas. In many mammals, the cerebral cortex consists of folded bulges called gyri that create deep furrows or fissures called sulci. The folds increase the surface area of the cortex and therefore increase the amount of gray matter and the amount of information that can be stored and processed.[45]

- The hippocampus, strictly speaking, is found only in mammals. However, the area it derives from, the medial pallium, has counterparts in all vertebrates. There is evidence that this part of the brain is involved in complex events such as spatial memory and navigation in fishes, birds, reptiles, and mammals.[46]

- The basal ganglia are a group of interconnected structures in the forebrain. The primary function of the basal ganglia appears to be action selection: they send inhibitory signals to all parts of the brain that can generate motor behaviors, and in the right circumstances can release the inhibition, so that the action-generating systems are able to execute their actions. Reward and punishment exert their most important neural effects by altering connections within the basal ganglia.[47]

- The olfactory bulb is a special structure that processes olfactory sensory signals and sends its output to the olfactory part of the pallium. It is a major brain component in many vertebrates, but is greatly reduced in humans and other primates (whose senses are dominated by information acquired by sight rather than smell).[48]

Reptiles

[edit]

Modern reptiles and mammals diverged from a common ancestor around 320 million years ago.[49] The number of extant reptiles far exceeds the number of mammalian species, with 11,733 recognized species of reptiles[50] compared to 5,884 extant mammals.[51] Along with the species diversity, reptiles have diverged in terms of external morphology, from limbless to tetrapod gliders to armored chelonians, reflecting adaptive radiation to a diverse array of environments.[52][53]

Morphological differences are reflected in the nervous system phenotype, such as: absence of lateral motor column neurons in snakes, which innervate limb muscles controlling limb movements; absence of motor neurons that innervate trunk muscles in tortoises; presence of innervation from the trigeminal nerve to pit organs responsible to infrared detection in snakes.[52] Variation in size, weight, and shape of the brain can be found within reptiles.[54] For instance, crocodilians have the largest brain volume to body weight proportion, followed by turtles, lizards, and snakes. Reptiles vary in the investment in different brain sections. Crocodilians have the largest telencephalon, while snakes have the smallest. Turtles have the largest diencephalon per body weight whereas crocodilians have the smallest. On the other hand, lizards have the largest mesencephalon.[54]

Yet their brains share several characteristics revealed by recent anatomical, molecular, and ontogenetic studies.[55][56][57] Vertebrates share the highest levels of similarities during embryological development, controlled by conserved transcription factors and signaling centers, including gene expression, morphological and cell type differentiation.[55][52][58] In fact, high levels of transcriptional factors can be found in all areas of the brain in reptiles and mammals, with shared neuronal clusters enlightening brain evolution.[56] Conserved transcription factors elucidate that evolution acted in different areas of the brain by either retaining similar morphology and function, or diversifying it.[55][56]

Anatomically, the reptilian brain has less subdivisions than the mammalian brain, however it has numerous conserved aspects including the organization of the spinal cord and cranial nerve, as well as elaborated brain pattern of organization.[59] Elaborated brains are characterized by migrated neuronal cell bodies away from the periventricular matrix, region of neuronal development, forming organized nuclear groups.[59] Aside from reptiles and mammals, other vertebrates with elaborated brains include hagfish, galeomorph sharks, skates, rays, teleosts, and birds.[59] Overall elaborated brains are subdivided in forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain.

The hindbrain coordinates and integrates sensory and motor inputs and outputs responsible for, but not limited to, walking, swimming, or flying. It contains input and output axons interconnecting the spinal cord, midbrain and forebrain transmitting information from the external and internal environments.[59] The midbrain links sensory, motor, and integrative components received from the hindbrain, connecting it to the forebrain. The tectum, which includes the optic tectum and torus semicircularis, receives auditory, visual, and somatosensory inputs, forming integrated maps of the sensory and visual space around the animal.[59] The tegmentum receives incoming sensory information and forwards motor responses to and from the forebrain. The isthmus connects the hindbrain with midbrain. The forebrain region is particularly well developed, is further divided into diencephalon and telencephalon. Diencephalon is related to regulation of eye and body movement in response to visual stimuli, sensory information, circadian rhythms, olfactory input, and autonomic nervous system.Telencephalon is related to control of movements, neurotransmitters and neuromodulators responsible for integrating inputs and transmitting outputs are present, sensory systems, and cognitive functions.[59]

Birds

[edit]

The avian brain is the central organ of the nervous system in birds. Birds possess large, complex brains, which process, integrate, and coordinate information received from the environment and make decisions on how to respond with the rest of the body. Like in all chordates, the avian brain is contained within the skull bones of the head.

The bird brain is divided into a number of sections, each with a different function. The cerebrum or telencephalon is divided into two hemispheres, and controls higher functions. The telencephalon is dominated by a large pallium, which corresponds to the mammalian cerebral cortex and is responsible for the cognitive functions of birds. The pallium is made up of several major structures: the hyperpallium, a dorsal bulge of the pallium found only in birds, as well as the nidopallium, mesopallium, and archipallium. The bird telencephalon nuclear structure, wherein neurons are distributed in three-dimensionally arranged clusters, with no large-scale separation of white matter and grey matter, though there exist layer-like and column-like connections. Structures in the pallium are associated with perception, learning, and cognition. Beneath the pallium are the two components of the subpallium, the striatum and pallidum. The subpallium connects different parts of the telencephalon and plays major roles in a number of critical behaviours. To the rear of the telencephalon are the thalamus, midbrain, and cerebellum. The hindbrain connects the rest of the brain to the spinal cord.

The size and structure of the avian brain enables prominent behaviours of birds such as flight and vocalization. Dedicated structures and pathways integrate the auditory and visual senses, strong in most species of birds, as well as the typically weaker olfactory and tactile senses. Social behaviour, widespread among birds, depends on the organisation and functions of the brain. Some birds exhibit strong abilities of cognition, enabled by the unique structure and physiology of the avian brain.Mammals

[edit]The most obvious difference between the brains of mammals and other vertebrates is their size. On average, a mammal has a brain roughly twice as large as that of a bird of the same body size, and ten times as large as that of a reptile of the same body size.[60]

Size, however, is not the only difference: there are also substantial differences in shape. The hindbrain and midbrain of mammals are generally similar to those of other vertebrates, but dramatic differences appear in the forebrain, which is greatly enlarged and also altered in structure.[61] The cerebral cortex is the part of the brain that most strongly distinguishes mammals. In non-mammalian vertebrates, the surface of the cerebrum is lined with a comparatively simple three-layered structure called the pallium. In mammals, the pallium evolves into a complex six-layered structure called neocortex or isocortex.[62] Several areas at the edge of the neocortex, including the hippocampus and amygdala, are also much more extensively developed in mammals than in other vertebrates.[61]

The elaboration of the cerebral cortex carries with it changes to other brain areas. The superior colliculus, which plays a major role in visual control of behavior in most vertebrates, shrinks to a small size in mammals, and many of its functions are taken over by visual areas of the cerebral cortex.[60] The cerebellum of mammals contains a large portion (the neocerebellum) dedicated to supporting the cerebral cortex, which has no counterpart in other vertebrates.[63]

In placentals, there is a wide nerve tract connecting the cerebral hemispheres called the corpus callosum.

Primates

[edit]| Species | EQ[64] |

|---|---|

| Human | 7.4–7.8 |

| Common chimpanzee | 2.2–2.5 |

| Rhesus monkey | 2.1 |

| Bottlenose dolphin | 4.14[65] |

| Elephant | 1.13–2.36[66] |

| Dog | 1.2 |

| Horse | 0.9 |

| Rat | 0.4 |

The brains of humans and other primates contain the same structures as the brains of other mammals, but are generally larger in proportion to body size.[67] The encephalization quotient (EQ) is used to compare brain sizes across species. It takes into account the nonlinearity of the brain-to-body relationship.[64] Humans have an average EQ in the 7-to-8 range, while most other primates have an EQ in the 2-to-3 range. Dolphins have values higher than those of primates other than humans,[65] but nearly all other mammals have EQ values that are substantially lower.

Most of the enlargement of the primate brain comes from a massive expansion of the cerebral cortex, especially the prefrontal cortex and the parts of the cortex involved in vision.[68] The visual processing network of primates includes at least 30 distinguishable brain areas, with a complex web of interconnections. It has been estimated that visual processing areas occupy more than half of the total surface of the primate neocortex.[69] The prefrontal cortex carries out functions that include planning, working memory, motivation, attention, and executive control. It takes up a much larger proportion of the brain for primates than for other species, and an especially large fraction of the human brain.[70]

Development

[edit]

The brain develops in an intricately orchestrated sequence of stages.[71] It changes in shape from a simple swelling at the front of the nerve cord in the earliest embryonic stages, to a complex array of areas and connections. Neurons are created in special zones that contain stem cells, and then migrate through the tissue to reach their ultimate locations. Once neurons have positioned themselves, their axons sprout and navigate through the brain, branching and extending as they go, until the tips reach their targets and form synaptic connections. In a number of parts of the nervous system, neurons and synapses are produced in excessive numbers during the early stages, and then the unneeded ones are pruned away.[71]

For vertebrates, the early stages of neural development are similar across all species.[71] As the embryo transforms from a round blob of cells into a wormlike structure, a narrow strip of ectoderm running along the midline of the back is induced to become the neural plate, the precursor of the nervous system. The neural plate folds inward to form the neural groove, and then the lips that line the groove merge to enclose the neural tube, a hollow cord of cells with a fluid-filled ventricle at the center. At the front end, the ventricles and cord swell to form three vesicles that are the precursors of the prosencephalon (forebrain), mesencephalon (midbrain), and rhombencephalon (hindbrain). At the next stage, the forebrain splits into two vesicles called the telencephalon (which will contain the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, and related structures) and the diencephalon (which will contain the thalamus and hypothalamus). At about the same time, the hindbrain splits into the metencephalon (which will contain the cerebellum and pons) and the myelencephalon (which will contain the medulla oblongata). Each of these areas contains proliferative zones where neurons and glial cells are generated; the resulting cells then migrate, sometimes for long distances, to their final positions.[71]

Once a neuron is in place, it extends dendrites and an axon into the area around it. Axons, because they commonly extend a great distance from the cell body and need to reach specific targets, grow in a particularly complex way. The tip of a growing axon consists of a blob of protoplasm called a growth cone, studded with chemical receptors. These receptors sense the local environment, causing the growth cone to be attracted or repelled by various cellular elements, and thus to be pulled in a particular direction at each point along its path. The result of this pathfinding process is that the growth cone navigates through the brain until it reaches its destination area, where other chemical cues cause it to begin generating synapses. Considering the entire brain, thousands of genes create products that influence axonal pathfinding.[71]

The synaptic network that finally emerges is only partly determined by genes, though. In many parts of the brain, axons initially "overgrow", and then are "pruned" by mechanisms that depend on neural activity.[71] In the projection from the eye to the midbrain, for example, the structure in the adult contains a very precise mapping, connecting each point on the surface of the retina to a corresponding point in a midbrain layer. In the first stages of development, each axon from the retina is guided to the right general vicinity in the midbrain by chemical cues, but then branches very profusely and makes initial contact with a wide swath of midbrain neurons. The retina, before birth, contains special mechanisms that cause it to generate waves of activity that originate spontaneously at a random point and then propagate slowly across the retinal layer. These waves are useful because they cause neighboring neurons to be active at the same time; that is, they produce a neural activity pattern that contains information about the spatial arrangement of the neurons. This information is exploited in the midbrain by a mechanism that causes synapses to weaken, and eventually vanish, if activity in an axon is not followed by activity of the target cell. The result of this sophisticated process is a gradual tuning and tightening of the map, leaving it finally in its precise adult form.[72]

Similar things happen in other brain areas: an initial synaptic matrix is generated as a result of genetically determined chemical guidance, but then gradually refined by activity-dependent mechanisms, partly driven by internal dynamics, partly by external sensory inputs. In some cases, as with the retina-midbrain system, activity patterns depend on mechanisms that operate only in the developing brain, and apparently exist solely to guide development.[72]

In humans and many other mammals, new neurons are created mainly before birth, and the infant brain contains substantially more neurons than the adult brain.[71] There are, however, a few areas where new neurons continue to be generated throughout life. The two areas for which adult neurogenesis is well established are the olfactory bulb, which is involved in the sense of smell, and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, where there is evidence that the new neurons play a role in storing newly acquired memories. With these exceptions, however, the set of neurons that is present in early childhood is the set that is present for life. Glial cells are different: as with most types of cells in the body, they are generated throughout the lifespan.[73]

There has long been debate about whether the qualities of mind, personality, and intelligence can be attributed to heredity or to upbringing.[74] Although many details remain to be settled, neuroscience shows that both factors are important. Genes determine both the general form of the brain and how it reacts to experience, but experience is required to refine the matrix of synaptic connections, resulting in greatly increased complexity. The presence or absence of experience is critical at key periods of development.[75] Additionally, the quantity and quality of experience are important. For example, animals raised in enriched environments demonstrate thick cerebral cortices, indicating a high density of synaptic connections, compared to animals with restricted levels of stimulation.[76]

Physiology

[edit]The functions of the brain depend on the ability of neurons to transmit electrochemical signals to other cells, and their ability to respond appropriately to electrochemical signals received from other cells. The electrical properties of neurons are controlled by a wide variety of biochemical and metabolic processes, most notably the interactions between neurotransmitters and receptors that take place at synapses.[8]

Neurotransmitters and receptors

[edit]Neurotransmitters are chemicals that are released at synapses when the local membrane is depolarised and Ca2+ enters into the cell, typically when an action potential arrives at the synapse – neurotransmitters attach themselves to receptor molecules on the membrane of the synapse's target cell (or cells), and thereby alter the electrical or chemical properties of the receptor molecules. With few exceptions, each neuron in the brain releases the same chemical neurotransmitter, or combination of neurotransmitters, at all the synaptic connections it makes with other neurons; this rule is known as Dale's principle.[8] Thus, a neuron can be characterized by the neurotransmitters that it releases. The great majority of psychoactive drugs exert their effects by altering specific neurotransmitter systems. This applies to drugs such as cannabinoids, nicotine, heroin, cocaine, alcohol, fluoxetine, chlorpromazine, and many others.[77]

The two neurotransmitters that are most widely found in the vertebrate brain are glutamate, which almost always exerts excitatory effects on target neurons, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which is almost always inhibitory. Neurons using these transmitters can be found in nearly every part of the brain.[78] Because of their ubiquity, drugs that act on glutamate or GABA tend to have broad and powerful effects. Some general anesthetics act by reducing the effects of glutamate; most tranquilizers exert their sedative effects by enhancing the effects of GABA.[79]

There are dozens of other chemical neurotransmitters that are used in more limited areas of the brain, often areas dedicated to a particular function. Serotonin, for example—the primary target of many antidepressant drugs and many dietary aids—comes exclusively from a small brainstem area called the raphe nuclei.[80] Norepinephrine, which is involved in arousal, comes exclusively from a nearby small area called the locus coeruleus.[81] Other neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and dopamine have multiple sources in the brain but are not as ubiquitously distributed as glutamate and GABA.[82]

Electrical activity

[edit]

As a side effect of the electrochemical processes used by neurons for signaling, brain tissue generates electric fields when it is active. When large numbers of neurons show synchronized activity, the electric fields that they generate can be large enough to detect outside the skull, using electroencephalography (EEG)[83] or magnetoencephalography (MEG). EEG recordings, along with recordings made from electrodes implanted inside the brains of animals such as rats, show that the brain of a living animal is constantly active, even during sleep.[84] Each part of the brain shows a mixture of rhythmic and nonrhythmic activity, which may vary according to behavioral state. In mammals, the cerebral cortex tends to show large slow delta waves during sleep, faster alpha waves when the animal is awake but inattentive, and chaotic-looking irregular activity when the animal is actively engaged in a task, called beta and gamma waves. During an epileptic seizure, the brain's inhibitory control mechanisms fail to function and electrical activity rises to pathological levels, producing EEG traces that show large wave and spike patterns not seen in a healthy brain. Relating these population-level patterns to the computational functions of individual neurons is a major focus of current research in neurophysiology.[84]

Metabolism

[edit]All vertebrates have a blood–brain barrier that allows metabolism inside the brain to operate differently from metabolism in other parts of the body. The neurovascular unit regulates cerebral blood flow so that activated neurons can be supplied with energy. Glial cells play a major role in brain metabolism by controlling the chemical composition of the fluid that surrounds neurons, including levels of ions and nutrients.[85]

Brain tissue consumes a large amount of energy in proportion to its volume, hence large brains place severe metabolic demands on animals. The need to limit body weight in order, for example, to fly, has apparently led to selection for a reduction of brain size in some species, such as bats.[86] Most of the brain's energy consumption goes into sustaining the electric charge (membrane potential) of neurons.[85] Most vertebrate species devote between 2% and 8% of basal metabolism to the brain. In primates, however, the percentage is much higher—in humans it rises to 20–25%.[87] The energy consumption of the brain does not vary greatly over time, but active regions of the cerebral cortex consume somewhat more energy than inactive regions; this forms the basis for the functional brain imaging methods of PET, fMRI,[88] and NIRS.[89] The brain typically gets most of its energy from oxygen-dependent metabolism of glucose (i.e., blood sugar),[85] but ketones provide a major alternative source, together with contributions from medium chain fatty acids (caprylic and heptanoic acids),[90][91] lactate,[92] acetate,[93] and possibly amino acids.[94]

Function

[edit]

Information from the sense organs is collected in the brain. There it is used to determine what actions the organism is to take. The brain processes the raw data to extract information about the structure of the environment. Next it combines the processed information with information about the current needs of the animal and with memory of past circumstances. Finally, on the basis of the results, it generates motor response patterns. These signal-processing tasks require intricate interplay between a variety of functional subsystems.[95]

The function of the brain is to provide coherent control over the actions of an animal. A centralized brain allows groups of muscles to be co-activated in complex patterns; it also allows stimuli impinging on one part of the body to evoke responses in other parts, and it can prevent different parts of the body from acting at cross-purposes to each other.[95]

Perception

[edit]

The human brain is provided with information about light, sound, the chemical composition of the atmosphere, temperature, the position of the body in space (proprioception), the chemical composition of the bloodstream, and more. In other animals additional senses are present, such as the infrared heat-sense of snakes, the magnetic field sense of some birds, or the electric field sense mainly seen in aquatic animals.

Each sensory system begins with specialized receptor cells,[8] such as photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye, or vibration-sensitive hair cells in the cochlea of the ear. The axons of sensory receptor cells travel into the spinal cord or brain, where they transmit their signals to a first-order sensory nucleus dedicated to one specific sensory modality. This primary sensory nucleus sends information to higher-order sensory areas that are dedicated to the same modality. Eventually, via a way-station in the thalamus, the signals are sent to the cerebral cortex, where they are processed to extract the relevant features, and integrated with signals coming from other sensory systems.[8]

Motor control

[edit]Motor systems are areas of the brain that are involved in initiating body movements, that is, in activating muscles. Except for the muscles that control the eye, which are driven by nuclei in the midbrain, all the voluntary muscles in the body are directly innervated by motor neurons in the spinal cord and hindbrain.[8] Spinal motor neurons are controlled both by neural circuits intrinsic to the spinal cord, and by inputs that descend from the brain. The intrinsic spinal circuits implement many reflex responses, and contain pattern generators for rhythmic movements such as walking or swimming. The descending connections from the brain allow for more sophisticated control.[8]

The brain contains several motor areas that project directly to the spinal cord. At the lowest level are motor areas in the medulla and pons, which control stereotyped movements such as walking, breathing, or swallowing. At a higher level are areas in the midbrain, such as the red nucleus, which is responsible for coordinating movements of the arms and legs. At a higher level yet is the primary motor cortex, a strip of tissue located at the posterior edge of the frontal lobe. The primary motor cortex sends projections to the subcortical motor areas, but also sends a massive projection directly to the spinal cord, through the pyramidal tract. This direct corticospinal projection allows for precise voluntary control of the fine details of movements. Other motor-related brain areas exert secondary effects by projecting to the primary motor areas. Among the most important secondary areas are the premotor cortex, supplementary motor area, basal ganglia, and cerebellum.[8] In addition to all of the above, the brain and spinal cord contain extensive circuitry to control the autonomic nervous system which controls the movement of the smooth muscle of the body.[8]

| Area | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral horn | Spinal cord | Contains motor neurons that directly activate muscles[96] |

| Oculomotor nuclei | Midbrain | Contains motor neurons that directly activate the eye muscles[97] |

| Cerebellum | Hindbrain | Calibrates precision and timing of movements[8] |

| Basal ganglia | Forebrain | Action selection on the basis of motivation[98] |

| Motor cortex | Frontal lobe | Direct cortical activation of spinal motor circuits[99] |

| Premotor cortex | Frontal lobe | Groups elementary movements into coordinated patterns[8] |

| Supplementary motor area | Frontal lobe | Sequences movements into temporal patterns[100] |

| Prefrontal cortex | Frontal lobe | Planning and other executive functions[101] |

Sleep

[edit]Many animals alternate between sleeping and waking in a daily cycle. Arousal and alertness are also modulated on a finer time scale by a network of brain areas.[8] A key component of the sleep system is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a tiny part of the hypothalamus located directly above the point at which the optic nerves from the two eyes cross. The SCN contains the body's central biological clock. Neurons there show activity levels that rise and fall with a period of about 24 hours, circadian rhythms: these activity fluctuations are driven by rhythmic changes in expression of a set of "clock genes". The SCN continues to keep time even if it is excised from the brain and placed in a dish of warm nutrient solution, but it ordinarily receives input from the optic nerves, through the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT), that allows daily light-dark cycles to calibrate the clock.[102]

The SCN projects to a set of areas in the hypothalamus, brainstem, and midbrain that are involved in implementing sleep-wake cycles. An important component of the system is the reticular formation, a group of neuron-clusters scattered diffusely through the core of the lower brain. Reticular neurons send signals to the thalamus, which in turn sends activity-level-controlling signals to every part of the cortex. Damage to the reticular formation can produce a permanent state of coma.[8]

Sleep involves great changes in brain activity.[8] Until the 1950s it was generally believed that the brain essentially shuts off during sleep,[103] but this is now known to be far from true; activity continues, but patterns become very different. There are two types of sleep: REM sleep (with dreaming) and NREM (non-REM, usually without dreaming) sleep, which repeat in slightly varying patterns throughout a sleep episode. Three broad types of distinct brain activity patterns can be measured: REM, light NREM and deep NREM. During deep NREM sleep, also called slow wave sleep, activity in the cortex takes the form of large synchronized waves, whereas in the waking state it is noisy and desynchronized. Levels of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin drop during slow wave sleep, and fall almost to zero during REM sleep; levels of acetylcholine show the reverse pattern.[8]

Homeostasis

[edit]

For any animal, survival requires maintaining a variety of parameters of bodily state within a limited range of variation: these include temperature, water content, salt concentration in the bloodstream, blood glucose levels, blood oxygen level, and others.[104] The ability of an animal to regulate the internal environment of its body—the milieu intérieur, as the pioneering physiologist Claude Bernard called it—is known as homeostasis (Greek for "standing still").[105] Maintaining homeostasis is a crucial function of the brain. The basic principle that underlies homeostasis is negative feedback: any time a parameter diverges from its set-point, sensors generate an error signal that evokes a response that causes the parameter to shift back toward its optimum value.[104] (This principle is widely used in engineering, for example in the control of temperature using a thermostat.)

In vertebrates, the part of the brain that plays the greatest role is the hypothalamus, a small region at the base of the forebrain whose size does not reflect its complexity or the importance of its function.[104] The hypothalamus is a collection of small nuclei, most of which are involved in basic biological functions. Some of these functions relate to arousal or to social interactions such as sexuality, aggression, or maternal behaviors; but many of them relate to homeostasis. Several hypothalamic nuclei receive input from sensors located in the lining of blood vessels, conveying information about temperature, sodium level, glucose level, blood oxygen level, and other parameters. These hypothalamic nuclei send output signals to motor areas that can generate actions to rectify deficiencies. Some of the outputs also go to the pituitary gland, a tiny gland attached to the brain directly underneath the hypothalamus. The pituitary gland secretes hormones into the bloodstream, where they circulate throughout the body and induce changes in cellular activity.[106]

Motivation

[edit]

The individual animals need to express survival-promoting behaviors, such as seeking food, water, shelter, and a mate.[107] The motivational system in the brain monitors the current state of satisfaction of these goals, and activates behaviors to meet any needs that arise. The motivational system works largely by a reward–punishment mechanism. When a particular behavior is followed by favorable consequences, the reward mechanism in the brain is activated, which induces structural changes inside the brain that cause the same behavior to be repeated later, whenever a similar situation arises. Conversely, when a behavior is followed by unfavorable consequences, the brain's punishment mechanism is activated, inducing structural changes that cause the behavior to be suppressed when similar situations arise in the future.[108]

Most organisms studied to date use a reward–punishment mechanism: for instance, worms and insects can alter their behavior to seek food sources or to avoid dangers.[109] In vertebrates, the reward-punishment system is implemented by a specific set of brain structures, at the heart of which lie the basal ganglia, a set of interconnected areas at the base of the forebrain.[47] The basal ganglia are the central site at which decisions are made: the basal ganglia exert a sustained inhibitory control over most of the motor systems in the brain; when this inhibition is released, a motor system is permitted to execute the action it is programmed to carry out. Rewards and punishments function by altering the relationship between the inputs that the basal ganglia receive and the decision-signals that are emitted. The reward mechanism is better understood than the punishment mechanism, because its role in drug abuse has caused it to be studied very intensively. Research has shown that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a central role: addictive drugs such as cocaine, amphetamine, and nicotine either cause dopamine levels to rise or cause the effects of dopamine inside the brain to be enhanced.[110]

Learning and memory

[edit]Almost all animals are capable of modifying their behavior as a result of experience—even the most primitive types of worms. Because behavior is driven by brain activity, changes in behavior must somehow correspond to changes inside the brain. Already in the late 19th century theorists like Santiago Ramón y Cajal argued that the most plausible explanation is that learning and memory are expressed as changes in the synaptic connections between neurons.[111] Until 1970, however, experimental evidence to support the synaptic plasticity hypothesis was lacking. In 1971 Tim Bliss and Terje Lømo published a paper on a phenomenon now called long-term potentiation: the paper showed clear evidence of activity-induced synaptic changes that lasted for at least several days.[112] Since then technical advances have made these sorts of experiments much easier to carry out, and thousands of studies have been made that have clarified the mechanism of synaptic change, and uncovered other types of activity-driven synaptic change in a variety of brain areas, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum.[113] Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and physical activity appear to play a beneficial role in the process.[114]

Neuroscientists currently distinguish several types of learning and memory that are implemented by the brain in distinct ways:

- Working memory is the ability of the brain to maintain a temporary representation of information about the task that an animal is currently engaged in. This sort of dynamic memory is thought to be mediated by the formation of cell assemblies—groups of activated neurons that maintain their activity by constantly stimulating one another.[115]

- Episodic memory is the ability to remember the details of specific events. This sort of memory can last for a lifetime. Much evidence implicates the hippocampus in playing a crucial role: people with severe damage to the hippocampus sometimes show amnesia, that is, inability to form new long-lasting episodic memories.[116]

- Semantic memory is the ability to learn facts and relationships. This sort of memory is probably stored largely in the cerebral cortex, mediated by changes in connections between cells that represent specific types of information.[117]

- Instrumental learning is the ability for rewards and punishments to modify behavior. It is implemented by a network of brain areas centered on the basal ganglia.[118]

- Motor learning is the ability to refine patterns of body movement by practicing, or more generally by repetition. A number of brain areas are involved, including the premotor cortex, basal ganglia, and especially the cerebellum, which functions as a large memory bank for microadjustments of the parameters of movement.[119]

Research

[edit]

The field of neuroscience encompasses all approaches that seek to understand the brain and the rest of the nervous system.[8] Psychology seeks to understand mind and behavior, and neurology is the medical discipline that diagnoses and treats diseases of the nervous system. The brain is also the most important organ studied in psychiatry, the branch of medicine that works to study, prevent, and treat mental disorders.[120] Cognitive science seeks to unify neuroscience and psychology with other fields that concern themselves with the brain, such as computer science (artificial intelligence and similar fields) and philosophy.[121]

The oldest method of studying the brain is anatomical, and until the middle of the 20th century, much of the progress in neuroscience came from the development of better cell stains and better microscopes. Neuroanatomists study the large-scale structure of the brain as well as the microscopic structure of neurons and their components, especially synapses. Among other tools, they employ a plethora of stains that reveal neural structure, chemistry, and connectivity. In recent years, the development of immunostaining techniques has allowed investigation of neurons that express specific sets of genes. Also, functional neuroanatomy uses medical imaging techniques to correlate variations in human brain structure with differences in cognition or behavior.[122]

Neurophysiologists study the chemical, pharmacological, and electrical properties of the brain: their primary tools are drugs and recording devices. Thousands of experimentally developed drugs affect the nervous system, some in highly specific ways. Recordings of brain activity can be made using electrodes, either glued to the scalp as in EEG studies, or implanted inside the brains of animals for extracellular recordings, which can detect action potentials generated by individual neurons.[123] Because the brain does not contain pain receptors, it is possible using these techniques to record brain activity from animals that are awake and behaving without causing distress. The same techniques have occasionally been used to study brain activity in human patients with intractable epilepsy, in cases where there was a medical necessity to implant electrodes to localize the brain area responsible for epileptic seizures.[124] Functional imaging techniques such as fMRI are also used to study brain activity; these techniques have mainly been used with human subjects, because they require a conscious subject to remain motionless for long periods of time, but they have the great advantage of being noninvasive.[125]

Another approach to brain function is to examine the consequences of damage to specific brain areas. Even though it is protected by the skull and meninges, surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid, and isolated from the bloodstream by the blood–brain barrier, the delicate nature of the brain makes it vulnerable to numerous diseases and several types of damage. In humans, the effects of strokes and other types of brain damage have been a key source of information about brain function. Because there is no ability to experimentally control the nature of the damage, however, this information is often difficult to interpret. In animal studies, most commonly involving rats, it is possible to use electrodes or locally injected chemicals to produce precise patterns of damage and then examine the consequences for behavior.[127]

Computational neuroscience encompasses two approaches: first, the use of computers to study the brain; second, the study of how brains perform computation. On one hand, it is possible to write a computer program to simulate the operation of a group of neurons by making use of systems of equations that describe their electrochemical activity; such simulations are known as biologically realistic neural networks. On the other hand, it is possible to study algorithms for neural computation by simulating, or mathematically analyzing, the operations of simplified "units" that have some of the properties of neurons but abstract out much of their biological complexity. The computational functions of the brain are studied both by computer scientists and neuroscientists.[128]

Computational neurogenetic modeling is concerned with the study and development of dynamic neuronal models for modeling brain functions with respect to genes and dynamic interactions between genes.

Recent years have seen increasing applications of genetic and genomic techniques to the study of the brain[129] and a focus on the roles of neurotrophic factors and physical activity in neuroplasticity.[114] The most common subjects are mice, because of the availability of technical tools. It is now possible with relative ease to "knock out" or mutate a wide variety of genes, and then examine the effects on brain function. More sophisticated approaches are also being used: for example, using Cre-Lox recombination it is possible to activate or deactivate genes in specific parts of the brain, at specific times.[129]

Recent years have also seen rapid advances in single-cell sequencing technologies, and these have been used to leverage the cellular heterogeneity of the brain as a means of better understanding the roles of distinct cell types in disease and biology (as well as how genomic variants influence individual cell types). In 2024, investigators studied a large integrated dataset of almost 3 million nuclei from the human prefrontal cortext from 388 individuals.[130] In doing so, they annotated 28 cell types to evaluate expression and chromatin variation across gene families and drug targets. They identified about half a million cell type–specific regulatory elements and about 1.5 million single-cell expression quantitative trait loci (i.e., genomic variants with strong statistical associations with changes in gene expression within specific cell types), which were then used to build cell-type regulatory networks (the study also describes cell-to-cell communication networks). These networks were found to manifest cellular changes in aging and neuropsychiatric disorders. As part of the same investigation, a machine learning model was designed to accurately impute single-cell expression (this model prioritized ~250 disease-risk genes and drug targets with associated cell types).

History

[edit]The oldest brain to have been discovered was in Armenia in the Areni-1 cave complex. The brain, estimated to be over 5,000 years old, was found in the skull of a 12 to 14-year-old girl. Although the brains were shriveled, they were well preserved due to the climate found inside the cave.[131]

Early philosophers were divided as to whether the seat of the soul lies in the brain or heart. Aristotle favored the heart, and thought that the function of the brain was merely to cool the blood. Democritus, the inventor of the atomic theory of matter, argued for a three-part soul, with intellect in the head, emotion in the heart, and lust near the liver.[132] The unknown author of On the Sacred Disease, a medical treatise in the Hippocratic Corpus, came down unequivocally in favor of the brain, writing:

Men ought to know that from nothing else but the brain come joys, delights, laughter and sports, and sorrows, griefs, despondency, and lamentations. ... And by the same organ we become mad and delirious, and fears and terrors assail us, some by night, and some by day, and dreams and untimely wanderings, and cares that are not suitable, and ignorance of present circumstances, desuetude, and unskillfulness. All these things we endure from the brain, when it is not healthy...

— On the Sacred Disease, attributed to Hippocrates[133]

The Roman physician Galen also argued for the importance of the brain, and theorized in some depth about how it might work. Galen traced out the anatomical relationships among brain, nerves, and muscles, demonstrating that all muscles in the body are connected to the brain through a branching network of nerves. He postulated that nerves activate muscles mechanically by carrying a mysterious substance he called pneumata psychikon, usually translated as "animal spirits".[132] Galen's ideas were widely known during the Middle Ages, but not much further progress came until the Renaissance, when detailed anatomical study resumed, combined with the theoretical speculations of René Descartes and those who followed him. Descartes, like Galen, thought of the nervous system in hydraulic terms. He believed that the highest cognitive functions are carried out by a non-physical res cogitans, but that the majority of behaviors of humans, and all behaviors of animals, could be explained mechanistically.[132]

The first real progress toward a modern understanding of nervous function, though, came from the investigations of Luigi Galvani (1737–1798), who discovered that a shock of static electricity applied to an exposed nerve of a dead frog could cause its leg to contract. Since that time, each major advance in understanding has followed more or less directly from the development of a new technique of investigation. Until the early years of the 20th century, the most important advances were derived from new methods for staining cells.[134] Particularly critical was the invention of the Golgi stain, which (when correctly used) stains only a small fraction of neurons, but stains them in their entirety, including cell body, dendrites, and axon. Without such a stain, brain tissue under a microscope appears as an impenetrable tangle of protoplasmic fibers, in which it is impossible to determine any structure. In the hands of Camillo Golgi, and especially of the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the new stain revealed hundreds of distinct types of neurons, each with its own unique dendritic structure and pattern of connectivity.[135]

In the first half of the 20th century, advances in electronics enabled investigation of the electrical properties of nerve cells, culminating in work by Alan Hodgkin, Andrew Huxley, and others on the biophysics of the action potential, and the work of Bernard Katz and others on the electrochemistry of the synapse.[136] These studies complemented the anatomical picture with a conception of the brain as a dynamic entity. Reflecting the new understanding, in 1942 Charles Sherrington visualized the workings of the brain waking from sleep:

The great topmost sheet of the mass, that where hardly a light had twinkled or moved, becomes now a sparkling field of rhythmic flashing points with trains of traveling sparks hurrying hither and thither. The brain is waking and with it the mind is returning. It is as if the Milky Way entered upon some cosmic dance. Swiftly the head mass becomes an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern, always a meaningful pattern though never an abiding one; a shifting harmony of subpatterns.

— Sherrington, 1942, Man on his Nature[137]

The invention of electronic computers in the 1940s, along with the development of mathematical information theory, led to a realization that brains can potentially be understood as information processing systems. This concept formed the basis of the field of cybernetics, and eventually gave rise to the field now known as computational neuroscience.[138] The earliest attempts at cybernetics were somewhat crude in that they treated the brain as essentially a digital computer in disguise, as for example in John von Neumann's 1958 book, The Computer and the Brain.[139] Over the years, though, accumulating information about the electrical responses of brain cells recorded from behaving animals has steadily moved theoretical concepts in the direction of increasing realism.[138]

One of the most influential early contributions was a 1959 paper titled What the frog's eye tells the frog's brain: the paper examined the visual responses of neurons in the retina and optic tectum of frogs, and came to the conclusion that some neurons in the tectum of the frog are wired to combine elementary responses in a way that makes them function as "bug perceivers".[140] A few years later David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel discovered cells in the primary visual cortex of monkeys that become active when sharp edges move across specific points in the field of view—a discovery for which they won a Nobel Prize.[141] Follow-up studies in higher-order visual areas found cells that detect binocular disparity, color, movement, and aspects of shape, with areas located at increasing distances from the primary visual cortex showing increasingly complex responses.[142] Other investigations of brain areas unrelated to vision have revealed cells with a wide variety of response correlates, some related to memory, some to abstract types of cognition such as space.[143]

Theorists have worked to understand these response patterns by constructing mathematical models of neurons and neural networks, which can be simulated using computers.[138] Some useful models are abstract, focusing on the conceptual structure of neural algorithms rather than the details of how they are implemented in the brain; other models attempt to incorporate data about the biophysical properties of real neurons.[144] No model on any level is yet considered to be a fully valid description of brain function, though. The essential difficulty is that sophisticated computation by neural networks requires distributed processing in which hundreds or thousands of neurons work cooperatively—current methods of brain activity recording are only capable of isolating action potentials from a few dozen neurons at a time.[145]

Furthermore, even single neurons appear to be complex and capable of performing computations.[146] So, brain models that do not reflect this are too abstract to be representative of brain operation; models that do try to capture this are very computationally expensive and arguably intractable with present computational resources. However, the Human Brain Project is trying to build a realistic, detailed computational model of the entire human brain. The wisdom of this approach has been publicly contested, with high-profile scientists on both sides of the argument.

In the second half of the 20th century, developments in chemistry, electron microscopy, genetics, computer science, functional brain imaging, and other fields progressively opened new windows into brain structure and function. In the United States, the 1990s were officially designated as the "Decade of the Brain" to commemorate advances made in brain research, and to promote funding for such research.[147]

In the 21st century, these trends have continued, and several new approaches have come into prominence, including multielectrode recording, which allows the activity of many brain cells to be recorded all at the same time;[148] genetic engineering, which allows molecular components of the brain to be altered experimentally;[129] genomics, which allows variations in brain structure to be correlated with variations in DNA properties and neuroimaging.[149]

Society and culture

[edit]As food

[edit]

Animal brains are used as food in numerous cuisines.

In rituals

[edit]Some archaeological evidence suggests that the mourning rituals of European Neanderthals also involved the consumption of the brain.[150]

The Fore people of Papua New Guinea are known to eat human brains. In funerary rituals, those close to the dead would eat the brain of the deceased to create a sense of immortality. A prion disease called kuru has been traced to this.[151]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Saladin, Kenneth (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ a b von Bartheld, CS; Bahney, J; Herculano-Houzel, S (15 December 2016). "The search for true numbers of neurons and glial cells in the human brain: A review of 150 years of cell counting". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 524 (18): 3865–3895. doi:10.1002/cne.24040. ISSN 0021-9967. PMC 5063692. PMID 27187682.

- ^ Yuste, Rafael; Church, George M. (March 2014). "The new century of the brain" (PDF). Scientific American. 310 (3): 38–45. Bibcode:2014SciAm.310c..38Y. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0314-38. PMID 24660326. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14.

- ^ a b c Shepherd, GM (1994). Neurobiology. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-508843-4.

- ^ Sporns, O (2010). Networks of the Brain. MIT Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-262-01469-4.

- ^ Başar, E (2010). Brain-Body-Mind in the Nebulous Cartesian System: A Holistic Approach by Oscillations. Springer. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-4419-6134-1.

- ^ Singh, Inderbir (2006). "A Brief Review of the Techniques Used in the Study of Neuroanatomy". Textbook of Human Neuroanatomy (7th ed.). Jaypee Brothers. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-8061-808-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Kandel, Eric R.; Schwartz, James Harris; Jessell, Thomas M. (2000). Principles of neural science (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1. OCLC 42073108.

- ^ Douglas, RJ; Martin, KA (2004). "Neuronal circuits of the neocortex". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 27: 419–451. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144152. PMID 15217339.

- ^ Barnett, MW; Larkman, PM (2007). "The action potential". Practical Neurology. 7 (3): 192–197. PMID 17515599.

- ^ a b c Shepherd, Gordon M. (2004). "1. Introduction to synaptic circuits". The Synaptic Organization of the Brain (5th ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-515956-1.

- ^ Williams, RW; Herrup, K (1988). "The control of neuron number". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 11: 423–453. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.002231. PMID 3284447.

- ^ Heisenberg, M (2003). "Mushroom body memoir: from maps to models". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 4 (4): 266–275. doi:10.1038/nrn1074. PMID 12671643. S2CID 5038386.

- ^ a b Jacobs, DK; Nakanishi, N; Yuan, D; et al. (2007). "Evolution of sensory structures in basal metazoa". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (5): 712–723. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.326.2233. doi:10.1093/icb/icm094. PMID 21669752.

- ^ a b Balavoine, G (2003). "The segmented Urbilateria: A testable scenario". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 137–147. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.137. PMID 21680418.

- ^ Schmidt-Rhaesa, A (2007). The Evolution of Organ Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-19-856669-4.

- ^ Kristan, WB Jr.; Calabrese, RL; Friesen, WO (2005). "Neuronal control of leech behavior". Prog Neurobiol. 76 (5): 279–327. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.004. PMID 16260077. S2CID 15773361.

- ^ Barnes, RD (1987). Invertebrate Zoology (5th ed.). Saunders College Pub. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-03-008914-5.

- ^ a b Butler, AB (2000). "Chordate Evolution and the Origin of Craniates: An Old Brain in a New Head". Anatomical Record. 261 (3): 111–125. doi:10.1002/1097-0185(20000615)261:3<111::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 10867629.

- ^ Bulloch, TH; Kutch, W (1995). "Are the main grades of brains different principally in numbers of connections or also in quality?". In Breidbach O (ed.). The nervous systems of invertebrates: an evolutionary and comparative approach. Birkhäuser. p. 439. ISBN 978-3-7643-5076-5.

- ^ "Flybrain: An online atlas and database of the drosophila nervous system". Archived from the original on 1998-01-09. Retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ^ Konopka, RJ; Benzer, S (1971). "Clock Mutants of Drosophila melanogaster". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 68 (9): 2112–2116. Bibcode:1971PNAS...68.2112K. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. PMC 389363. PMID 5002428.

- ^ Shin, Hee-Sup; et al. (1985). "An unusual coding sequence from a Drosophila clock gene is conserved in vertebrates". Nature. 317 (6036): 445–448. Bibcode:1985Natur.317..445S. doi:10.1038/317445a0. PMID 2413365. S2CID 4372369.

- ^ Heisenberg, M; Heusipp, M; Wanke, C. (1995). "Structural plasticity in the Drosophila brain". J. Neurosci. 15 (3): 1951–1960. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01951.1995. PMC 6578107. PMID 7891144.

- ^ Brenner, Sydney (1974). "The Genetics of CAENORHABDITIS ELEGANS". Genetics. 77 (1): 71–94. doi:10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. PMC 1213120. PMID 4366476.

- ^ Hobert, O (2005). The C. elegans Research Community (ed.). "Specification of the nervous system". WormBook: 1–19. doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.12.1. PMC 4781215. PMID 18050401.

- ^ White, JG; Southgate, E; Thomson, JN; Brenner, S (1986). "The Structure of the Nervous System of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 314 (1165): 1–340. Bibcode:1986RSPTB.314....1W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. PMID 22462104.