Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Determiner phrase

View on WikipediaIn linguistics, a determiner phrase (DP) is a type of phrase headed by a determiner such as many.[1] Controversially, many approaches take a phrase like not very many apples to be a DP headed, in this case, by the determiner many. This is called the DP analysis or the DP hypothesis. Others reject this analysis in favor of the more traditional NP (noun phrase or nominal phrase) analysis where apples would be the head of the phrase in which the DP not very many is merely a dependent. Thus, there are competing analyses concerning heads and dependents in nominal groups.[2] The DP analysis developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s,[3] and it is the majority view in generative grammar today.[4]

In the example determiner phrases below, the determiners are in boldface:

- a little dog, the little dogs (indefinite or definite articles)

- my little dog, your little dogs (possessives)

- this little dog, those little dogs (demonstratives)

- every little dog, each little dog, no dog (quantifiers)

The competing analyses

[edit]Although the DP analysis is the dominant view in generative grammar, most other grammar theories reject the idea. For instance, representational phrase structure grammars follow the NP analysis, e.g. Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar, and most dependency grammars such as Meaning-Text Theory, Functional Generative Description, and Lexicase Grammar also assume the traditional NP analysis of noun phrases, Word Grammar being the one exception.[1] Construction Grammar and Role and Reference Grammar also assume NP instead of DP. Noam Chomsky, on whose framework most generative grammar has been built, said in a 2020 lecture,

I’m going to assume here that nominal phrases are actually NPs. The DP hypothesis, which is widely accepted, was very fruitful, leading to a lot of interesting work; but I’ve never really been convinced by it. I think these structures are fundamentally nominal phrases. [. . . ] As far as determiners are concerned, like say that, I suspect that they are adjuncts. So I’ll be assuming that the core system is basically nominal.[5]

The point at issue concerns the hierarchical status of determiners. Various types of determiners in English are summarized in the following table.

| Article | Quantifier | Demonstrative | Possessive |

|---|---|---|---|

| a/an, the | all, every, many, each, etc. | this, that, those, etc. | my, your, her, its, their, etc. |

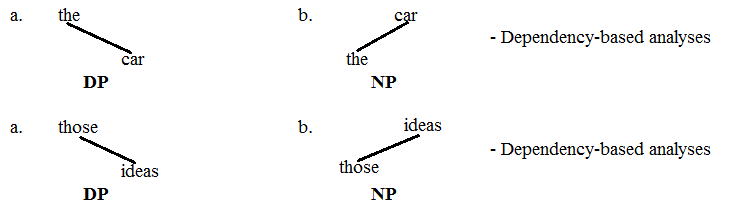

Should the determiner in phrases such as the car and those ideas be construed as the head of or as a dependent in the phrase? The following trees illustrate the competing analyses, DP vs. NP. The two possibilities are illustrated first using dependency-based structures (of dependency grammars):

The a-examples show the determiners dominating the nouns, and the b-examples reverse the relationship, since the nouns dominate the determiners. The same distinction is illustrated next using constituency-based trees (of phrase structure grammars), which are equivalent to the above:

The convention used here employs the words themselves as the labels on the nodes in the structure. Whether a dependency-based or constituency-based approach to syntax is employed, the issue is which word is the head over the other.

Arguments for DP over NP

[edit]The DP-hypothesis is held for four main reasons: 1) facilitates viewing phrases and clauses as structurally parallel, 2) accounts for determiners often introducing phrases and their fixed position within phrases, 3) accounts for possessive -s constructions, and 4) accounts for the behaviour of definite pronouns given their complementary distribution with determiners.

Parallel structures

[edit]The original motivation for the DP-analysis came in the form of parallelism across phrase and clause. The DP-analysis provides a basis for viewing clauses and phrases as structurally parallel.[6] The basic insight runs along the following lines: since clauses have functional categories above lexical categories, noun phrases should do the same. The traditional NP-analysis has the drawback that it positions the determiner, which is often a pure function word, below the lexical noun, which is usually a full content word. The traditional NP-analysis is therefore unlike the analysis of clauses, which positions the functional categories as heads over the lexical categories. The point is illustrated by drawing a parallel to the analysis of auxiliary verbs. Given a combination such as will understand, one views the modal auxiliary verb will, a function word, as head over the main verb understand, a content word. Extending this type of analysis to a phrase like the car, the determiner the, a function word, should be head over car, a content word. In so doing, the NP the car becomes a DP. The point is illustrated with simple dependency-based hierarchies:

Only the DP-analysis shown in c establishes the parallelism with the verb chain. It enables one to assume that the architecture of syntactic structure is principled; functional categories (function words) consistently appear above lexical categories (content words) in phrases and clauses. This unity of the architecture of syntactic structure is perhaps the strongest argument in favor of the DP-analysis.

Position

[edit]The fact that determiners typically introduce the phrases in which they appear is also viewed as support for the DP-analysis. One points to the fact that when more than one attributive adjective appears, their order is somewhat flexible, e.g. an old friendly dog vs. a friendly old dog. The position of the determiner, in contrast, is fixed; it has to introduce the phrase, e.g. *friendly an old dog, *old friendly a dog, etc. The fact that the determiner's position at the left-most periphery of the phrase is set is taken as an indication that it is the head of the phrase. The reasoning assumes that the architecture of phrases is robust if the position of the head is fixed. The flexibility of order for attributive adjectives is taken as evidence that they are indeed dependents of the noun.

Possessive -s in English

[edit]Possessive -s constructions in English are often produced as evidence in favor of the DP-analysis.[7] The key trait of the possessive -s construction is that the -s can attach to the right periphery of a phrase. This fact means that -s is not a suffix (since suffixes attach to words, not phrases). Further, the possessive -s construction has the same distribution as determiners, which means that it has determiner status. The assumption is therefore that possessive -s heads the entire DP, e.g.

- [the guy with a hat]'s dog

- [the girl who was laughing]'s scarf

The phrasal nature of the possessive -s constructions like these is easy to accommodate on a DP-analysis. The possessive -s heads the possessive phrase; the phrase that immediately precedes the -s (in brackets) is in specifier position, and the noun that follows the -s is the complement. The claim is that the NP-analysis is challenged by this construction because it does not make a syntactic category available for the analysis of -s, that is, the NP-analysis does not have a clear means at its disposal to grant -s the status of determiner. This claim is debatable, however, since nothing prevents the NP-analysis from also granting -s the status of determiner. The NP-analysis is however forced to acknowledge that DPs do in fact exist, since possessive -s constructions have to be acknowledged as phrases headed by the determiner -s. A certain type of DP definitely exists, namely one that has -s as its head.

Definite pronouns

[edit]The fact that definite pronouns are in complementary distribution with determiners is taken as evidence in favor of DP.[8] The important observation in this area is that definite pronouns cannot appear together with a determiner like the or a in one and the same DP, e.g.

- they

- *the they

- him

- *a him

On a DP-analysis, this trait of definite pronouns is relatively easy to account for. If definite pronouns are actually determiners, then it makes sense that they should not be able to appear together with another determiner since the two would be competing for the same syntactic position in the hierarchy of structure. On an NP-analysis in contrast, there is no obvious reason why a combination of the two would not be possible. In other words, the NP-analysis has to reach to additional stipulations to account for the fact that combinations like *the them are impossible. A difficulty with this reasoning, however, is posed by indefinite pronouns (one, few, many), which can easily appear together with a determiner, e.g. the old one. The DP-analysis must therefore draw a distinction between definite and indefinite pronouns, whereby definite pronouns are classified as determiners, but indefinite pronouns as nouns.

Arguments for NP over DP

[edit]While the DP-hypothesis has largely replaced the traditional NP analysis in generative grammar, it is generally not held among advocates of other frameworks, for six reasons:[9] 1) absent determiners, 2) morphological dependencies, 3) semantic and syntactic parallelism, 4) idiomatic expressions, 5) left-branch phenomena, and 6) genitives.

Absent determiners

[edit]Many languages lack the equivalents of the English definite and indefinite articles, e.g. the Slavic languages. Thus in these languages, determiners appear much less often than in English, where the definite article the and the indefinite article a are frequent. What this means for the DP-analysis is that null determiners are a common occurrence in these languages. In other words, the DP-analysis must posit the frequent occurrence of null determiners in order to remain consistent about its analysis of DPs. DPs that lack an overt determiner actually involve a covert determiner in some sense. The problem is evident in English as well, where mass nouns can appear with or without a determiner, e.g. milk vs. the milk, water vs. the water. Plural nouns can also appear with or without a determiner, e.g. books vs. the books, ideas vs. the ideas, etc. Since nouns that lack an overt determiner have the same basic distribution as nouns with a determiner, the DP-analysis should, if it wants to be consistent, posit the existence of a null determiner every time an overt determiner is absent. The traditional NP analysis is not confronted with this necessity, since for it, the noun is the head of the noun phrase regardless of whether a determiner is or is not present. Thus the traditional NP analysis requires less of the theoretical apparatus, since it does not need all those null determiners, the existence of which is non-falsifiable. Other things being equal, less is better according to Occam's Razor.

Morphological dependencies

[edit]The NP-analysis is consistent with intuition in the area of morphological dependencies. Semantic and grammatical features of the noun influence the choice and morphological form of the determiner, not vice versa. Consider grammatical gender of nouns in a language like German, e.g. Tisch 'table' is masculine (der Tisch), Haus 'house' is neuter (das Haus), Zeit 'time' is feminine (die Zeit). The grammatical gender of a noun is an inherent trait of the noun, whereas the form of the determiner varies according to this trait of the noun. In other words, the noun is influencing the choice and form of the determiner, not vice versa. In English, this state of affairs is visible in the area of grammatical number, for instance with the opposition between singular this and that and plural these and those. Since the NP-analysis positions the noun above the determiner, the influence of the noun on the choice and form of the determiner is intuitively clear: the head noun is influencing the dependent determiner. The DP-analysis, in contrast, is unintuitive because it necessitates that one view the dependent noun as influencing the choice and form of the head determiner.

Semantic and structural parallelism

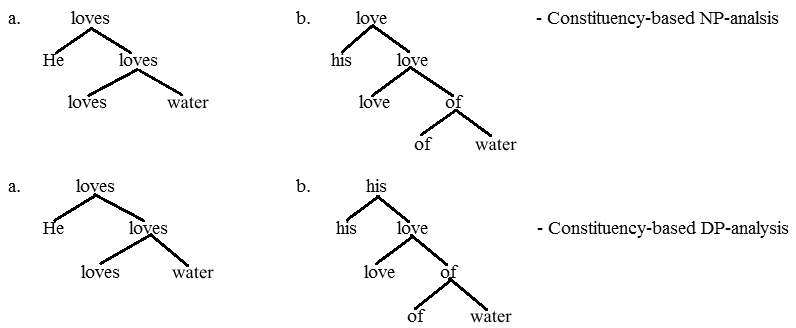

[edit]Despite what was stated above about parallelism across clause and DP, the traditional NP-analysis of noun phrases actually maintains parallelism in a way that is destroyed if one assumes DPs. The semantic parallelism that can be obtained across clause and NP, e.g. He loves water vs. his love of water, is no longer present in the structure if one assumes DPs. The point is illustrated here first with dependency trees:

On the NP-analysis, his is a dependent of love in the same way that he is a dependent of loves. The result is that the NP his love of water and the clause He loves water are mostly parallel in structure, which seems correct given the semantic parallelism across the two. In contrast, the DP analysis destroys the parallelism, since his becomes head over love. The same point is true for a constituency-based analysis:

These trees again employ the convention whereby the words themselves are used as the node labels. The NP-analysis maintains the parallelism because the determiner his appears as specifier in the NP headed by love in the same way that he appears as specifier in the clause headed by loves. In contrast, the DP analysis destroys this parallelism because his no longer appears as a specifier in the NP, but rather as head over the noun.

Idiomatic meaning

[edit]The fixed words of many idioms in natural language include the noun of a noun phrase at the same time that they exclude the determiner.[10] This is particularly true of many idioms in English that require the presence of a possessor that is not a fixed part of the idiom, e.g. take X's time, pull X's leg, dance on X's grave, step on X's toes, etc. While the presence of the Xs in these idioms is required, the X argument itself is not fixed, e.g. pull his/her/their/John's leg. What this means is that the possessor is not part of the idiom; it is outside of the idiom. This fact is a problem for the DP-analysis because it means that the fixed words of the idiom are interrupted in the vertical dimension. That is, the hierarchical arrangement of the fixed words is interrupted by the possessor, which is not part of the idiom. The traditional NP-analysis is not confronted with this problem, since the possessor appears below the noun. The point is clearly visible in dependency-based structures:

The arrangement of the words in the vertical dimension is what is important. The fixed words of the idiom (in blue) are top-down continuous on the NP-analysis (they form a catena), whereas this continuity is destroyed on the DP-analysis, where the possessor (in green) intervenes. Therefore the NP-analysis allows one to construe idioms as chains of words, whereas on the DP-analysis, one cannot make this assumption. On the DP-analysis, the fixed words of many idioms really cannot be viewed as discernible units of syntax in any way.

Left branches

[edit]In English and many closely related languages, constituents on left branches underneath nouns cannot be separated from their nouns. Long-distance dependencies are impossible between a noun and the constituents that normally appear on left branches underneath the noun. This fact is addressed in terms of the Left Branch Condition.[11] Determiners and attributive adjectives are typical "left-branch constituents". The observation is illustrated with examples of topicalization and wh-fronting:

(1a) Fred has helpful friends. (1b) *...and helpful Fred has friends. - The attributive adjective helpful cannot be topicalized away from its head friends.

(2a) Sam is waiting for the second train. (2b) *...and second Sam is waiting for the train. - The attributive adjective second cannot be topicalized away from its head train.

(3a) Susan has our car. (3b) *Whose does Susan have car? - The interrogative determiner whose cannot be wh-fronted away from its head car.

(4a) Sam is waiting for the second train. (4b) *Which is Sam waiting for train? - The interrogative determiner which cannot be wh-fronted away from its head train.

These examples illustrate that with respect to the long-distance dependencies of topicalization and wh-fronting, determiners behave like attributive adjectives. Both cannot be separated from their head noun. The NP-analysis is consistent with this observation because it positions both attributive adjectives and determiners as left-branch dependents of nouns. On a DP-analysis, however, determiners are no longer on left branches underneath nouns. In other words, the traditional NP-analysis is consistent with the fact that determiners behave just like attributive adjectives with respect to long-distance dependencies, whereas the DP-analysis cannot appeal to left branches to account for this behavior because on the DP-analysis, the determiner is no longer on a left branch underneath the noun.

Genitives

[edit]The NP-analysis is consistent with the observation that genitive case in languages like German can have the option to appear before or after the noun, whereby the meaning remains largely the same, as illustrated with the following examples:

- a. das Haus meines Bruders 'the house of.my brother'

- b. meines Bruders Haus 'my brother's house'

- a. die Arbeit seines Onkels 'the work of.his uncle'

- b. seines Onkels Arbeit 'his uncle's work'

While the b-phrases are somewhat archaic, they still occur on occasion in elevated registers. The fact that the genitive NPs meines Bruders and seines Onkels can precede or follow the noun is telling, since it suggests that the hierarchical analysis of the two variants should be similar in a way that accommodates the almost synonymous meanings. On the NP-analysis, these data are not a problem because in both cases, the genitive expression is a dependent of the noun. The DP-analysis, in contrast, is challenged because in the b-variants, it takes the genitive expression to be head over the noun. In other words, the DP-analysis has to account for the fact that the meaning remains consistent despite the quite different structures across the two variants.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Müller, Stefan (2016). Grammatical theory: From transformational grammar to constraint-based approaches. Language Science Press. doi:10.26530/oapen_611693. ISBN 978-3-944675-21-3.

- ^ Müller, Stefan (2016). Grammatical theory: From transformational grammar to constraint-based approaches. Language Science Press. p. 29. doi:10.26530/oapen_611693. ISBN 978-3-944675-21-3.

- ^ Several early works that helped establish the DP-analysis are Vennemann & Harlow (1977), Brame (1982), Szabolcsi (1983), Hudson (1984), Muysken & van Reimsdijk (1986), and Abney (1987).

- ^ Poole (19??: ???) states that the DP-analysis is the majority stance in generative grammar today.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (2020). "The UCLA lectures (April 29 – May 2, 2019)". lingbuzz.net. p. 51.

- ^ Bernstein (2008) develops the point that the DP-analysis increases parallelism across clauses and phrases.

- ^ For an example of possessive -s used as an argument in favor of DPs, see Carnie (2021: 214-217).

- ^ Hordós et al. produce the behavior of definite pronouns as an argument in favor of the DP-analysis.

- ^ Three articles that discuss observations and arguments against the DP-analysis and in favor of the NP-analysis are Payne (1993), Langendonck (1994), and Hudson (2004).

- ^ The fact that the fixed words of idioms are continuous in the vertical dimension is explored by Osborne et al. (2012).

- ^ The Left Branch Condition was first identified and explored by Ross (1967).

References

[edit]- Abney, S. P. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. Ph. D. thesis, MIT, Cambridge MA.

- Brame, M. 1982. The head selector theory of lexical specifications and the non-existence of coarse categories. Linguistic Analysis, 10, 321-325.

- Bernstein, J. B. 2008. Reformulating the determiner phrase analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2: 1246–1270.

- Carnie, A. 2013. Syntax: A Generative introduction, 3rd Edition. Wiley-Blackwill.

- Carnie, A. 2021. Syntax: A Generative introduction, 4th Edition. Wiley-Blackwill.

- Coene, M. and Y. D'Hulst. 2003. Introduction: The syntax and semantics of noun phrases. From NP to DP. (1):9.

- Eichler, N., Hager, M., and Müller, N. 2012. Code-switching within determiner phrases in bilingual children: French, italian, spanish and german. Zeitschrift Für Französische Sprache Und Literatur 122 (3): 227.

- Hordós M., M. Newson, D. Pap., K. Szécsényi, G. Tóth Gabriella., and V. Vincz. 2006. Basic English syntax with exercises. Bölcsész Konzorcium. Available at http://primus.arts.u-szeged.hu/bese/Chapter4/4.1.htm.

- Hudson, R. 1984. Word Grammar. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Hudson, R. 2004. Are determiners heads? Functions of Language, 11(1): 7-42.

- Langendonck, W. van 1994. Determiners as heads? Cognitive Linguistics 5, 3: 243-260.

- Longobardi, G. 1994. Reference and proper names: A theory of N-movement in syntax and Logical Form. Università di Venezia

- MacLaughlin, D. 1997. The structure of determiner phrases: Evidence from American sign language. ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing).

- Manlove, K. 2015. Evidence for a DP-projection in West Greenlandic Inuit. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 60 (3): 327.

- Payne, John (1993). "The Headedness of Noun Phrases: Slaying the Nominal Hydra". In Corbett, Greville G.; Fraser, Norman M.; McGlashan, Scott (eds.). Heads in Grammatical Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 114–139. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511659454.006. ISBN 9780521420709.

- Progovac, L. 1998. Determiner phrase in a language without determiners (with apologies to jim huang 1982). Journal of Linguistics 34 (1): 165-79.

- Osborne, T., M. Putnam, and T. Groß 2012. Catenae: Introducing a novel unit of syntactic analysis. Syntax 15, 4, 354-396.

- Poole, G. 2002. Syntactic Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Szabolcsi, A. 1983. The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review, 3(1), 89-102.

Determiner phrase

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

In linguistics, a determiner phrase (DP) is a syntactic constituent that functions as the maximal projection of a determiner, which serves as its head. The determiner, often a functional element such as an article (e.g., "the" or "a"), a demonstrative (e.g., "this" or "that"), or a quantifier (e.g., "every" or "some"), combines with a nominal complement to form referential expressions that denote entities or sets. This structure allows determiners to license the noun phrase and its modifiers, enabling the DP to occupy argument positions in sentences, such as subjects or objects.[1] The core components of a DP include the determiner (D) as the head, which selects a noun phrase (NP) as its complement, typically consisting of the noun and its immediate modifiers like adjectives. Specifiers, such as possessors (e.g., "John's" in "John's book"), may occupy the specifier position of DP, while adjuncts like attributive adjectives (e.g., "red" in "the red book") attach within the NP. In possessive constructions, the D head may be phonologically null or realized as genitive marking ('s), assigning case to the possessor in specifier position. This organization reflects X-bar theory principles, where the D head projects the DP structure with specifier, head, and complement positions.[1] A basic representation of DP structure can be depicted as follows, using bracketed notation for a simple definite DP:[DP [D the] [NP [N book]]]

[DP [D the] [NP [N book]]]

Historical Development

The concept of the determiner phrase (DP) emerged in the 1980s as an extension of X-bar theory, which had previously treated noun phrases (NPs) as endocentric projections headed by the noun in generative grammar frameworks developed in the 1970s.[3] Early ideas building on this foundation explored functional categories within nominal structures, with researchers like Paul Postal noting parallels between pronouns and determiners, suggesting determiners could function as heads rather than mere specifiers. These developments shifted focus from the noun-centric NP views dominant in the 1970s, as seen in Chomsky's (1970) and Jackendoff's (1977) formulations, toward recognizing determiners' central role.[1][3] A pivotal advancement came with Steven Abney's 1987 dissertation, which systematically proposed the DP hypothesis, arguing that determiners head a functional projection parallel to inflectional phrases (IPs) and complementizer phrases (CPs) in clausal structure.[1] Abney's analysis unified various nominal constructions, such as possessives and gerunds, by positing DP as the maximal projection containing an NP complement, thereby resolving issues like the licensing of PRO subjects in nominals. This work built directly on cross-linguistic evidence, particularly from Hungarian, where Anna Szabolcsi (1987) demonstrated functional categories akin to inflection and complementizers within noun phrases, with determiners enabling argumenthood.[4] Szabolcsi's observations of possessor agreement and determiner positioning provided empirical support for treating D as a head parallel to clausal Infl.[4] Further refinements in the early 1990s strengthened the DP framework, notably through Giuseppe Longobardi's (1994) analysis of proper names, which argued that nouns must raise to the D position for referential interpretation, distinguishing argumental from predicative uses.[5] This movement-based account integrated DP with semantic requirements, influencing subsequent generative research. By the mid-1990s, the DP hypothesis had gained widespread acceptance, appearing as standard in generative syntax textbooks and analyses. In the evolution toward the Minimalist Program, introduced by Noam Chomsky in 1995, the DP integrated with core operations like feature checking and Merge, treating functional heads such as D as essential for case and phi-feature valuation. This framework further embedded DP within phase theory from the early 2000s, where nominal phases align with clausal ones for economy-driven derivations. The shift from 1970s NP-centric models to DP adoption marked a major theoretical realignment, solidifying by the late 1990s in mainstream generative linguistics.Theoretical Foundations

Determiner Phrase Hypothesis

The Determiner Phrase Hypothesis proposes that determiners, such as articles, demonstratives, and possessives, project their own phrasal category known as the Determiner Phrase (DP), thereby treating the determiner as the head of the nominal structure with the noun phrase (NP) functioning as its complement.[1] This approach ensures endocentricity in nominal phrases, meaning every phrase is headed by an element of the same category, and establishes parallelism with other functional projections like the Tense Phrase (TP, formerly IP) and Complementizer Phrase (CP), where functional heads similarly dominate lexical projections.[1] The primary motivations for this hypothesis lie in achieving uniformity across phrase structures in generative syntax, aligning with X-bar theory's principles that all major categories head maximal projections.[1] Under the traditional view, determiners occupied the specifier position of an NP, creating an exocentric relation that deviated from the head-complement asymmetry seen in verbal or adjectival phrases; the DP hypothesis reframes the determiner-noun relation as a canonical head-complement configuration, where the determiner selects the NP as its sister, promoting consistency in syntactic architecture.[1] Formally, the DP adheres to X-bar theory's template for phrasal expansion:Here, D (the determiner head) projects to D' and then DP, with the NP serving as the complement of D, mirroring structures like VP where V heads and selects a complement.[1] This framework integrates with theta-theory by positing that determiners introduce referentiality or quantificational force at the functional layer of the nominal domain, akin to how tense in TP contributes temporal interpretation.[1] The hypothesis was first systematically developed in Abney's 1987 dissertation.[1]

Noun Phrase Analysis

In the traditional analysis of the noun phrase within generative grammar prior to the 1980s, the noun phrase (NP) is conceptualized as an endocentric construction headed by the noun (N), with determiners functioning as specifiers or adjuncts internal to the NP rather than as heads of a distinct projection.[6] This view, foundational to early X-bar theory, posits that the NP serves as the maximal projection encompassing all nominal elements, including articles, demonstratives, possessives, and quantifiers, which modify the head noun without introducing an additional layer of structure. The approach emphasizes uniformity across phrasal categories, treating NPs alongside verb phrases and other projections under a generalized schema.[6] The structural representation of the NP in this framework follows X-bar principles, typically formalized as [{NP} [{Spec} Det] [{N'} N [{PP/AP} complements]]], where the specifier position hosts the determiner, and the N' intermediate projection includes the head noun along with its complements (e.g., prepositional phrases) or adjuncts (e.g., adjectives). Jackendoff (1977) extends this to a multi-level bar structure, allowing multiple specifiers at levels such as N'', N''', with determiners occupying higher specifier slots to accommodate elements like genitives or quantifiers in complementary distribution.[6] For instance, in "the cat," "the" appears in the specifier of NP, sister to N' dominated by the head "cat," while adjuncts like adjectives adjoin to N' or higher bars. This lacks any separate determiner projection, maintaining a flat or layered organization centered on the lexical noun.[6] Central assumptions of this NP analysis hold that nouns inherently bear the predicative content and primary referential load, denoting classes or properties that determiners then modify to specify reference, definiteness, or quantity without altering the head's categorial status. Determiners are thus viewed as optional modifiers that restrict the noun's denotation, such as linking it to discourse context or numerical scope, rather than projecting their own phrase to encode referentiality.[6] Proper nouns, for example, achieve direct reference independently, underscoring the noun's core role in argumenthood. Early generative models illustrate these principles through uniform treatment of determiners. In Jackendoff (1977), possessives like "John's" and quantifiers like "many" occupy specifier positions equivalently, as in [{NP} John's [{N'} book]] or [{N'''} many [{N''} [_{N'} books]]], ensuring parallel handling across nominal constructions without distinguishing possessive from definite determiners structurally. Adjective phrases, such as "very proud" in "very proud woman," may derive via movement to a specifier or adjunction, reinforcing the NP's internal hierarchy.[6] This perspective began shifting in the 1980s toward functional projections like the determiner phrase.[6]Arguments Supporting DP Hypothesis

Structural Parallels with Other Phrases

The determiner phrase (DP) hypothesis posits that noun phrases are embedded within a functional projection headed by a determiner (D), creating structural parallels with other major phrasal categories in the X-bar schema of generative syntax. This mirroring is evident in how DP aligns with the complementizer phrase (CP), where the functional head C selects an infinitival or tensed clause (IP/TP); the inflectional phrase (IP/TP), where the functional head T introduces tense and selects a verb phrase (VP); and the adjective phrase (AP), where the lexical head A projects functional layers for degree modification or comparison. These parallels arise because functional heads like D, C, and T introduce abstract features such as case, definiteness, or agreement, unifying the architecture across categories and supporting a consistent hierarchical organization in universal grammar.[1] Evidence for this symmetry comes from the capacity for recursion and embedding within DPs, akin to the layered functional structure in CPs and TPs. Determiners enable recursive embedding of possessors or modifiers, as in recursive constructions like "John's friend's book," where multiple specifier positions allow successive functional projections similar to how complementizers embed clauses (e.g., "that she thinks that he left"). Gerunds further illustrate this, embedding VP complements under DP (e.g., "John's [discovering [a thesis-writing algorithm]]"), behaving internally like clausal structures while externally patterning as nominals, a parallelism reinforced cross-linguistically in languages like Turkish with genitive-marked gerunds. This recursive potential of determiners mirrors the embedding of TPs under CPs, facilitating complex subordination without violating X-bar principles.[1][1] The uniform X-bar schema is exemplified by comparing a simple DP like "the big dog" to a clausal structure like "that she runs." In tree form:DP

├── Spec: (empty or possessor)

└── D':

├── D: the

└── NP:

├── Spec: big (AP)

└── N':

└── N: dog

DP

├── Spec: (empty or possessor)

└── D':

├── D: the

└── NP:

├── Spec: big (AP)

└── N':

└── N: dog

CP

├── Spec: (empty)

└── C':

├── C: that

└── TP:

├── Spec: she

└── T':

├── T: (tense)

└── VP: runs

CP

├── Spec: (empty)

└── C':

├── C: that

└── TP:

├── Spec: she

└── T':

├── T: (tense)

└── VP: runs