Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Generative grammar

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

Generative grammar is a research tradition in linguistics that aims to explain the cognitive basis of language by formulating and testing explicit models of humans' subconscious grammatical knowledge. Generative linguists tend to share certain working assumptions such as the competence–performance distinction and the notion that some domain-specific aspects of grammar are partly innate in humans. These assumptions are often rejected in non-generative approaches such as usage-based models of language. Generative linguistics includes work in core areas such as syntax, semantics, phonology, psycholinguistics, and language acquisition, with additional extensions to topics including biolinguistics and music cognition.

Generative grammar began in the late 1950s with the work of Noam Chomsky, having roots in earlier approaches such as structural linguistics. The earliest version of Chomsky's model was called Transformational grammar, with subsequent iterations known as Government and binding theory and the Minimalist program. Other present-day generative models include Optimality theory, Categorial grammar, and Tree-adjoining grammar.

Principles

[edit]Generative grammar is an umbrella term for a variety of approaches to linguistics. What unites these approaches is the goal of uncovering the cognitive basis of language by formulating and testing explicit models of humans' subconscious grammatical knowledge.[1][2]

Cognitive science

[edit]Generative grammar studies language as part of cognitive science. Thus, research in the generative tradition involves formulating and testing hypotheses about the mental processes that allow humans to use language.[3][4][5]

Like other approaches in linguistics, generative grammar engages in linguistic description rather than linguistic prescription.[6][7]

Explicitness and generality

[edit]Generative grammar proposes models of language consisting of explicit rule systems, which make testable falsifiable predictions. This is different from traditional grammar where grammatical patterns are often described more loosely.[8][9] These models are intended to be parsimonious, capturing generalizations in the data with as few rules as possible. As a result, empirical research in generative linguistics often seeks to identify commonalities between phenomena, and theoretical research seems to provide them with unified explanations. For example, Paul Postal observed that English imperative tag questions obey the same restrictions that second person future declarative tags do, and proposed that the two constructions are derived from the same underlying structure. This hypothesis was able to explain the restrictions on tags using a single rule.[8]

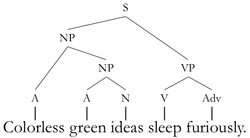

Particular theories within generative grammar have been expressed using a variety of formal systems, many of which are modifications or extensions of context free grammars.[8]

Competence versus performance

[edit]Generative grammar generally distinguishes linguistic competence and linguistic performance.[10] Competence is the collection of subconscious rules that one knows when one knows a language; performance is the system which puts these rules to use.[10][11] This distinction is related to the broader notion of Marr's levels used in other cognitive sciences, with competence corresponding to Marr's computational level.[12]

For example, generative theories generally provide competence-based explanations for why English speakers would judge the sentence in (1) as odd. In these explanations, the sentence would be ungrammatical because the rules of English only generate sentences where demonstratives agree with the grammatical number of their associated noun.[13]

- (1) *That cats is eating the mouse.

By contrast, generative theories generally provide performance-based explanations for the oddness of center embedding sentences like one in (2). According to such explanations, the grammar of English could in principle generate such sentences, but doing so in practice is so taxing on working memory that the sentence ends up being unparsable.[13][14]

- (2) *The cat that the dog that the man fed chased meowed.

In general, performance-based explanations deliver a simpler theory of grammar at the cost of additional assumptions about memory and parsing. As a result, the choice between a competence-based explanation and a performance-based explanation for a given phenomenon is not always obvious and can require investigating whether the additional assumptions are supported by independent evidence.[14][15] For example, while many generative models of syntax explain island effects by positing constraints within the grammar, it has also been argued that some or all of these constraints are in fact the result of limitations on performance.[16][17]

Non-generative approaches often do not posit any distinction between competence and performance. For instance, usage-based models of language assume that grammatical patterns arise as the result of usage.[18]

Innateness and universality

[edit]A major goal of generative research is to figure out which aspects of linguistic competence are innate and which are not. Within generative grammar, it is generally accepted that at least some domain-specific aspects are innate, and the term "universal grammar" is often used as a placeholder for whichever those turn out to be.[19][20]

The idea that at least some aspects are innate is motivated by poverty of the stimulus arguments.[21][22] For example, one famous poverty of the stimulus argument concerns the acquisition of yes–no questions in English. This argument starts from the observation that children only make mistakes compatible with rules targeting hierarchical structure even though the examples which they encounter could have been generated by a simpler rule that targets linear order. In other words, children seem to ignore the possibility that the question rule is as simple as "switch the order of the first two words" and immediately jump to alternatives that rearrange constituents in tree structures. This is taken as evidence that children are born knowing that grammatical rules involve hierarchical structure, even though they have to figure out what those rules are.[21][22][23] The empirical basis of poverty of the stimulus arguments has been challenged by Geoffrey Pullum and others, leading to back-and-forth debate in the language acquisition literature.[24][25] Recent work has also suggested that some recurrent neural network architectures are able to learn hierarchical structure without an explicit constraint.[26]

Within generative grammar, there are a variety of theories about what universal grammar consists of. One notable hypothesis proposed by Hagit Borer holds that the fundamental syntactic operations are universal and that all variation arises from different feature-specifications in the lexicon.[20][27] On the other hand, a strong hypothesis adopted in some variants of Optimality Theory holds that humans are born with a universal set of constraints, and that all variation arises from differences in how these constraints are ranked.[20][28] In a 2002 paper, Noam Chomsky, Marc Hauser and W. Tecumseh Fitch proposed that universal grammar consists solely of the capacity for hierarchical phrase structure.[29]

In day-to-day research, the notion that universal grammar exists motivates analyses in terms of general principles. As much as possible, facts about particular languages are derived from these general principles rather than from language-specific stipulations.[19]

Subfields

[edit]Research in generative grammar spans a number of subfields. These subfields are also studied in non-generative approaches.

Syntax

[edit]Syntax studies the rule systems which combine smaller units such as morphemes into larger units such as phrases and sentences.[30] Within generative syntax, prominent approaches include Minimalism, Government and binding theory, Lexical-functional grammar (LFG), and Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG).[2]

Phonology

[edit]Phonology studies the rule systems which organize linguistic sounds. For example, research in phonology includes work on phonotactic rules which govern which phonemes can be combined, as well as those that determine the placement of stress, tone, and other suprasegmental elements.[31] Within generative grammar, a prominent approach to phonology is Optimality Theory.[28]

Semantics

[edit]Semantics studies the rule systems that determine expressions' meanings. Within generative grammar, semantics is a species of formal semantics, providing compositional models of how the denotations of sentences are computed on the basis of the meanings of the individual morphemes and their syntactic structure.[32]

Extensions

[edit]Music

[edit]Generative grammar has been applied to music theory and analysis.[33] One notable approach is Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff's 1983 Generative theory of tonal music, which formalized and extended ideas from Schenkerian analysis.[34] Though Lerdahl and Jackendoff observed that their model of musical syntax was quite different from then-current models of linguistic syntax, recent work by Jonah Katz and David Pesetsky has argued for a closer connection. According to Katz and Pesetsky's Identity Thesis for Language and Music, linguistic syntax and musical syntax are formally equivalent except that the former operates on morphemes while the latter operates on pitch classes.[35][36]

Biolinguistics

[edit]Biolinguistics is the study of the biology of language. Recent work in generative-inspired biolinguistics has proposed the hypothesis that universal grammar consists solely of syntactic recursion, and that it arose recently in humans as the result of a random genetic mutation.[37]

History

[edit]As a distinct research tradition, generative grammar began in the late 1950s with the work of Noam Chomsky.[38] However, its roots include earlier structuralist approaches such as glossematics which themselves had older roots, for instance in the work of the ancient Indian grammarian Pāṇini.[39][40][41] Military funding to generative research was an important factor in its early spread in the 1960s.[42]

The initial version of generative syntax was called transformational grammar. In transformational grammar, rules called transformations mapped a level of representation called deep structures to another level of representation called surface structure. The semantic interpretation of a sentence was represented by its deep structure, while the surface structure provided its pronunciation. For example, an active sentence such as "The doctor examined the patient" and "The patient was examined by the doctor", had the same deep structure. The difference in surface structures arises from the application of the passivization transformation, which was assumed to not affect meaning. This assumption was challenged in the 1960s by the discovery of examples such as "Everyone in the room knows two languages" and "Two languages are known by everyone in the room".[43]

After the Linguistics wars of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Chomsky developed a revised model of syntax called Government and binding theory, which eventually grew into Minimalism. In the aftermath of those disputes, a variety of other generative models of syntax were proposed including relational grammar, Lexical-functional grammar (LFG), and Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG).[44]

Generative phonology originally focused on rewrite rules, in a system commonly known as SPE Phonology after the 1968 book The Sound Pattern of English by Chomsky and Morris Halle. In the 1990s, this approach was largely replaced by Optimality theory, which was able to capture generalizations called conspiracies which needed to be stipulated in SPE phonology.[28]

Semantics emerged as a subfield of generative linguistics during the late 1970s, with the pioneering work of Richard Montague. Montague proposed a system called Montague grammar which consisted of interpretation rules mapping expressions from a bespoke model of syntax to formulas of intensional logic. Subsequent work by Barbara Partee, Irene Heim, Tanya Reinhart, and others showed that the key insights of Montague Grammar could be incorporated into more syntactically plausible systems.[45][46]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wasow, Thomas (2003). "Generative Grammar" (PDF). In Aronoff, Mark; Ress-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell. pp. 296, 311. doi:10.1002/9780470756409.ch12.

...generative grammar is not so much a theory as a family or theories, or a school of thought... [having] shared assumptions and goals, widely used formal devices, and generally accepted empirical results

- ^ a b Carnie, Andrew (2002). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-631-22543-0.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2002). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 4–6, 8. ISBN 978-0-631-22543-0.

- ^ Wasow, Thomas (2003). "Generative Grammar" (PDF). In Aronoff, Mark; Ress-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell. pp. 295–296, 299–300. doi:10.1002/9780470756409.ch12. ISBN 978-0-631-20497-8.

- ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0199243709.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2002). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-631-22543-0.

- ^ Wasow, Thomas (2003). "Generative Grammar" (PDF). In Aronoff, Mark; Ress-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell. pp. 295, 297. doi:10.1002/9780470756409.ch12. ISBN 978-0-631-20497-8.

- ^ a b c Wasow, Thomas (2003). "Generative Grammar" (PDF). In Aronoff, Mark; Ress-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell. pp. 298–300. doi:10.1002/9780470756409.ch12. ISBN 978-0-631-20497-8.

- ^ Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0199243709.

- ^ a b Wasow, Thomas (2003). "Generative Grammar" (PDF). In Aronoff, Mark; Ress-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell. pp. 297–298. doi:10.1002/9780470756409.ch12.

- ^ Pritchett, Bradley (1992). Grammatical competence and parsing performance. University of Chicago Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-226-68442-3.

- ^ Marr, David (1982). Vision. MIT Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0262514620.

- ^ a b Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–7, 17. ISBN 978-0199243709.

- ^ a b Dillon, Brian; Momma, Shota (2021), Psychological background to linguistic theories (PDF) (Course notes)

- ^ Sprouse, Jon; Wagers, Matt; Phillips, Colin (2013). "Deriving competing predictions from grammatical approaches and reductionist approaches to island effects". In Sprouse, Jon; Hornstein, Norbert (eds.). Experimental syntax and island effects. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139035309.002 (inactive 1 July 2025).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Phillips, Colin (2013). "On the nature of island constraints I: Language processing and reductionist accounts" (PDF). In Sprouse, Jon; Hornstein, Norbert (eds.). Experimental syntax and island effects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–108. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139035309.005. ISBN 978-1-139-03530-9.

- ^ Hofmeister, Philip; Staum Casasanto, Laura; Sag, Ivan (2013). "Islands in the grammar? Standards of evidence". In Sprouse, Jon; Hornstein, Norbert (eds.). Experimental syntax and island effects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–63. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139035309.004. ISBN 978-1-139-03530-9.

- ^ Vyvyan, Evans; Green, Melanie (2006). Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 108–111. ISBN 0-7486-1832-5.

- ^ a b Wasow, Thomas (2003). "Generative Grammar" (PDF). In Aronoff, Mark; Ress-Miller, Janie (eds.). The Handbook of Linguistics. Blackwell. p. 299. doi:10.1002/9780470756409.ch12.

- ^ a b c Pesetsky, David (1999). "Linguistic universals and universal grammar". In Wilson, Robert; Keil, Frank (eds.). The MIT encyclopedia of the cognitive sciences. MIT Press. pp. 476–478. doi:10.7551/mitpress/4660.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-33816-5.

- ^ a b Adger, David (2003). Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-0199243709.

- ^ a b Lasnik, Howard; Lidz, Jeffrey (2017). "The Argument from the Poverty of the Stimulus" (PDF). In Roberts, Ian (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Universal Grammar. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Crain, Stephen; Nakayama, Mineharu (1987). "Structure dependence in grammar formation". Language. 63 (3): 522–543. doi:10.2307/415004. JSTOR 415004.

- ^ Pullum, Geoff; Scholz, Barbara (2002). "Empirical assessment of stimulus poverty arguments". The Linguistic Review. 18 (1–2): 9–50. doi:10.1515/tlir.19.1-2.9.

- ^ Legate, Julie Anne; Yang, Charles (2002). "Empirical re-assessment of stimulus poverty arguments" (PDF). The Linguistic Review. 18 (1–2): 151–162. doi:10.1515/tlir.19.1-2.9.

- ^ McCoy, R. Thomas; Frank, Robert; Linzen, Tal (2018). "Revisiting the poverty of the stimulus: hierarchical generalization without a hierarchical bias in recurrent neural networks" (PDF). Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society: 2093–2098.

- ^ Gallego, Ángel (2012). "Parameters". In Boeckx, Cedric (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199549368.013.0023.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, John (1992). Doing optimality theory. Wiley. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4051-5136-8.

- ^ Hauser, Marc; Chomsky, Noam; Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2002). "The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve". Science. 298 (5598): 1569–1579. doi:10.1126/science.298.5598.1569. PMID 12446899.

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2002). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-631-22543-0.

- ^ Clements, Nick (1999). "Phonology". In Wilson, Robert; Keil, Frank (eds.). The MIT encyclopedia of the cognitive sciences. MIT Press. pp. 639–641. doi:10.7551/mitpress/4660.003.0026.

- ^ Irene Heim; Angelika Kratzer (1998). Semantics in generative grammar. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19713-3.

- ^ Baroni, Mario; Maguire, Simon; Drabkin, William (1983). "The Concept of Musical Grammar". Music Analysis. 2 (2): 175–208. doi:10.2307/854248. JSTOR 854248.

- ^ Lerdahl, Fred; Ray Jackendoff (1983). A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-62107-6.

- ^ Katz, Jonah; Pesetsky, David (2011). "The Identity Thesis for Language and Music" (PDF).

- ^ Zeijlstra, Hedde (2020). "Rethinking remerge: Merge, movement and music" (PDF). In Bárány, András; Biberauer, Theresa; Douglas, Jamie; Vikner, Sten (eds.). Syntactic architecture and its consequences II: Between syntax and morphology. Language Science Press.

- ^ Berwick, Robert; Chomsky, Noam (2015). Why Only Us: Language and Evolution. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262034241.

- ^ Newmeyer, Frederick (1986). Linguistic Theory in America. Academic Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-12-517152-8.

- ^ Koerner, E. F. K. (1978). "Towards a historiography of linguistics". Toward a Historiography of Linguistics: Selected Essays. John Benjamins. pp. 21–54.

- ^ Bloomfield, Leonard, 1929, 274; cited in Rogers, David, 1987, 88

- ^ Hockett, Charles, 1987, 41

- ^ Newmeyer, F. J. (1986). Has there been a 'Chomskyan revolution' in linguistics?. Language, 62(1), p.13

- ^ Heitner, Reese (2003-10-03). "An Integrated Theory of Linguistic Descriptions [1964]". The Philosophical Forum. 34 (3–4): 401–416. doi:10.1111/1467-9191.00147. ISSN 0031-806X.

- ^ Sadler, Louisa; Nordlinger, Rachel (2018-12-13), Audring, Jenny; Masini, Francesca (eds.), "Morphology in Lexical-Functional Grammar and Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar", The Oxford Handbook of Morphological Theory, Oxford University Press, pp. 211–243, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199668984.013.17, ISBN 978-0-19-966898-4, retrieved 2025-05-08

- ^ Partee, Barbara (2011). "Formal semantics: Origins, issues, early impact". The Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication. 6. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.826.5720.

- ^ Crnič, Luka; Pesetsky, David; Sauerland, Uli (2014). "Introduction: Biographical Notes" (PDF). In Crnič, Luka; Sauerland, Uli (eds.). The art and craft of semantics: A Festschrift for Irene Heim.

Further reading

[edit]- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Hurford, J. (1990) Nativist and functional explanations in language acquisition. In I. M. Roca (ed.), Logical Issues in Language Acquisition, 85–136. Foris, Dordrecht.

- Marantz, Alec (2019). "What do linguists do?" (PDF).

- Isac, Daniela; Charles Reiss (2013). I-language: An Introduction to Linguistics as Cognitive Science, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953420-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Generative linguistics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Generative linguistics at Wikimedia Commons