Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agreed definition of the lower boundary for their size.[1][2] In a narrower sense, a city can be defined as a permanent and densely populated place with administratively defined boundaries whose members work primarily on non-agricultural tasks.[3] Cities generally have extensive systems for housing, transportation, sanitation, utilities, land use, production of goods, and communication. Their density facilitates interaction between people, government organizations, and businesses, sometimes benefiting different parties in the process, such as improving the efficiency of goods and service distribution.

Historically, city dwellers have been a small proportion of humanity overall, but following two centuries of unprecedented and rapid urbanization, more than half of the world population now lives in cities, which has had profound consequences for global sustainability.[4][5] Present-day cities usually form the core of larger metropolitan areas and urban areas—creating numerous commuters traveling toward city centres for employment, entertainment, and education. However, in a world of intensifying globalization, all cities are to varying degrees also connected globally beyond these regions. This increased influence means that cities also have significant influences on global issues, such as sustainable development, climate change, and global health. Because of these major influences on global issues, the international community has prioritized investment in sustainable cities through Sustainable Development Goal 11. Due to the efficiency of transportation and the smaller land consumption, dense cities hold the potential to have a smaller ecological footprint per inhabitant than more sparsely populated areas.[6] Therefore, compact cities are often referred to as a crucial element in fighting climate change.[7] However, this concentration can also have some significant harmful effects, such as forming urban heat islands, concentrating pollution, and stressing water supplies and other resources.

Meaning

[edit]Urban settlements

[edit]Common population definitions for an urban area (city or town) range between 1,500 and 50,000 people, with most U.S. states using a minimum between 1,500 and 5,000 inhabitants.[8][9] Some jurisdictions set no such criteria.[10]

National censuses use a variety of definitions – invoking factors such as population, population density, number of dwellings, economic function, and infrastructure – to classify populations as urban.[11]

City

[edit]

A city can be distinguished from other human settlements by its relatively great size, but also by its functions and its special symbolic status, which may be conferred by a central authority. The term can also refer either to the physical streets and buildings of the city or to the collection of people who dwell there and can be used in a general sense to mean urban rather than rural territory.[13][14]

According to the "functional definition", a city is not distinguished by size alone, but also by the role it plays within a larger political context. Cities serve as administrative, commercial, religious, and cultural hubs for their larger surrounding areas.[15][16] The presence of a literate elite is often associated with cities because of the cultural diversities present in a city.[17][18] A typical city has professional administrators, regulations, and some form of taxation (food and other necessities or means to trade for them) to support the government workers. (This arrangement contrasts with the more typically horizontal relationships in a tribe or village accomplishing common goals through informal agreements between neighbors, or the leadership of a chief.) The governments may be based on heredity, religion, military power, work systems such as canal-building, food distribution, land-ownership, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing, finance, or a combination of these. Societies that live in cities are often called civilizations.

Population size, density

[edit]The degree of urbanization is a modern metric to help define what comprises a city: "a population of at least 50,000 inhabitants in contiguous dense grid cells (>1,500 inhabitants per square kilometer)".[19] This metric was "devised over years by the European Commission, OECD, World Bank and others, and endorsed in March [2021] by the United Nations ... largely for the purpose of international statistical comparison".[20] Typical working definitions for small-city populations start at around 100,000 people.[11]

In specific countries

[edit]In Australia, the definition of what constitutes a city varies between the states.[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom, city status is awarded by the Crown and then remains permanent, with only two exceptions to this rule due to policy changes. A lack of official qualifying criteria results in some particularly small cities, notably St Davids with a population of 1,751 as of 2021[update].

Etymology

[edit]The word city comes from the Latin word citadel i.e. fortress. The related (maybe) civilization come from the Latin root civitas, originally meaning 'citizenship' or 'community member' and eventually coming to correspond with urbs, meaning 'city' in a more physical sense.[13] The Roman civitas was closely linked with the Greek polis—another common root appearing in English words such as metropolis.[21]

In toponymic terminology, names of individual cities and towns are called astionyms (from Ancient Greek ἄστυ 'city or town' and ὄνομα 'name').[22]

Geography

[edit]Urban geography deals both with cities in their larger context and with their internal structure.[23] Cities are estimated to cover about 3% of the land surface of the Earth.[24]

Site

[edit]

Town siting has varied through history according to natural, technological, economic, and military contexts. Access to water has long been a major factor in city placement and growth, and despite exceptions enabled by the advent of rail transport in the nineteenth century, through the present most of the world's urban population lives near the coast or on a river.[25]

Urban areas as a rule cannot produce their own food and therefore must develop some relationship with a hinterland that sustains them.[26] Only in special cases such as mining towns which play a vital role in long-distance trade, are cities disconnected from the countryside which feeds them.[27] Thus, centrality within a productive region influences siting, as economic forces would, in theory, favor the creation of marketplaces in optimal mutually reachable locations.[28]

Center

[edit]

The vast majority of cities have a central area containing buildings with special economic, political, and religious significance. Archaeologists refer to this area by the Greek term temenos or if fortified as a citadel.[29] These spaces historically reflect and amplify the city's centrality and importance to its wider sphere of influence.[28] Today cities have a city center or downtown, sometimes coincident with a central business district.

Public space

[edit]

Cities typically have public spaces where anyone can go. These include privately owned spaces open to the public as well as forms of public land such as public domain and the commons. Western philosophy since the time of the Greek agora has considered physical public space as the substrate of the symbolic public sphere.[30][31] Public art adorns (or disfigures) public spaces. Parks and other natural sites within cities provide residents with relief from the hardness and regularity of typical built environments. Urban green spaces are another component of public space that provides the benefit of mitigating the urban heat island effect, especially in cities that are in warmer climates. These spaces prevent carbon imbalances, extreme habitat losses, electricity and water consumption, and human health risks.[32]

Internal structure

[edit]

The urban structure generally follows one or more basic patterns: geomorphic, radial, concentric, rectilinear, and curvilinear. The physical environment generally constrains the form in which a city is built. If located on a mountainside, urban structures may rely on terraces and winding roads. It may be adapted to its means of subsistence (e.g. agriculture or fishing). And it may be set up for optimal defense given the surrounding landscape.[33] Beyond these "geomorphic" features, cities can develop internal patterns, due to natural growth or to city planning.

In a radial structure, main roads converge on a central point. This form could evolve from successive growth over a long time, with concentric traces of town walls and citadels marking older city boundaries. In more recent history, such forms were supplemented by ring roads moving traffic around the outskirts of a town. Dutch cities such as Amsterdam and Haarlem are structured as a central square surrounded by concentric canals marking every expansion. In cities such as Moscow, this pattern is still clearly visible.

A system of rectilinear city streets and land plots, known as the grid plan, has been used for millennia in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The Indus Valley Civilization built Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, and other cities on a grid pattern, using ancient principles described by Kautilya, and aligned with the compass points.[34][15][35][36] The ancient Greek city of Priene exemplifies a grid plan with specialized districts used across the Hellenistic Mediterranean.

Urban areas

[edit]The urban-type settlement extends far beyond the traditional boundaries of the city proper[37] in a form of development sometimes described critically as urban sprawl.[38] Decentralization and dispersal of city functions (commercial, industrial, residential, cultural, political) has transformed the very meaning of the term and has challenged geographers seeking to classify territories according to an urban-rural binary.[9]

Metropolitan areas include suburbs and exurbs organized around the needs of commuters, and sometimes edge cities characterized by a degree of economic and political independence. (In the US these are grouped into metropolitan statistical areas for purposes of demography and marketing.) Some cities are now part of a continuous urban landscape called urban agglomeration, conurbation, or megalopolis (exemplified by the BosWash corridor of the Northeastern United States.)[39]

History

[edit]

The emergence of cities from proto-urban settlements, such as Çatalhöyük, is a non-linear development that demonstrates the varied experiences of early urbanization.[40] The cities of Jericho, Aleppo, Byblos, Faiyum, Yerevan, Athens, Matera, Damascus, and Argos are among those laying claim to the longest continual inhabitation.[41][42]

Cities, characterized by population density, symbolic function, and urban planning, have existed for thousands of years.[43] In the conventional view, civilization and the city were both followed by the development of agriculture, which enabled the production of surplus food and thus a social division of labor (with concomitant social stratification) and trade.[44][45] Early cities often featured granaries, sometimes within a temple.[46] A minority viewpoint considers that cities may have arisen without agriculture, due to alternative means of subsistence (fishing),[47] to use as communal seasonal shelters,[48] to their value as bases for defensive and offensive military organization,[49][50] or to their inherent economic function.[51][52][53] Cities played a crucial role in the establishment of political power over an area, and ancient leaders such as Alexander the Great founded and created them with zeal.[54]

Ancient times

[edit]

Jericho and Çatalhöyük, dated to the eighth millennium BC, are among the earliest proto-cities known to archaeologists.[48][55] However, the Mesopotamian city of Uruk from the mid-fourth millennium BC (ancient Iraq) is considered by most archaeologists to be the first true city, innovating many characteristics for cities to follow, with its name attributed to the Uruk period.[56][57][58]

In the fourth and third millennium BC, complex civilizations flourished in the river valleys of Mesopotamia, India,[59][60] China,[61] and Egypt. Excavations in these areas have found the ruins of cities geared variously towards trade, politics, or religion. Some had large, dense populations, but others carried out urban activities in the realms of politics or religion without having large associated populations.

Among the early Old World cities, Mohenjo-daro of the Indus Valley civilization in present-day Pakistan, existing from about 2600 BC, was one of the largest, with a population of 50,000 or more and a sophisticated sanitation system.[62] China's planned cities were constructed according to sacred principles to act as celestial microcosms.[63]

The Ancient Egyptian cities known physically by archaeologists are not extensive.[15] They include (known by their Arab names) El Lahun, a workers' town associated with the pyramid of Senusret II, and the religious city Amarna built by Akhenaten and abandoned. These sites appear planned in a highly regimented and stratified fashion, with a minimalistic grid of rooms for the workers and increasingly more elaborate housing available for higher classes.[64]

In Mesopotamia, the civilization of Sumer, followed by Assyria and Babylon, gave rise to numerous cities, governed by kings and fostered multiple languages written in cuneiform.[65] The Phoenician trading empire, flourishing around the turn of the first millennium BC, encompassed numerous cities extending from Tyre, Cydon, and Byblos to Carthage and Cádiz.

In the following centuries, independent city-states of Greece, especially Athens, developed the polis, an association of male landowning citizens who collectively constituted the city.[66] The agora, meaning "gathering place" or "assembly", was the center of the athletic, artistic, spiritual, and political life of the polis.[67] Rome was the first city that surpassed one million inhabitants. Under the authority of its empire, Rome transformed and founded many cities (Colonia), and with them brought its principles of urban architecture, design, and society.[68]

In the ancient Americas, early urban traditions developed in the Andes and Mesoamerica. In the Andes, the first urban centers developed in the Norte Chico civilization, Chavin and Moche cultures, followed by major cities in the Huari, Chimu, and Inca cultures. The Norte Chico civilization included as many as 30 major population centers in what is now the Norte Chico region of north-central coastal Peru. It is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, flourishing between the 30th and 18th centuries BC.[69] Mesoamerica saw the rise of early urbanism in several cultural regions, beginning with the Olmec and spreading to the Preclassic Maya, the Zapotec of Oaxaca, and Teotihuacan in central Mexico. Later cultures such as the Aztec, Andean civilizations, Mayan, Mississippians, and Pueblo peoples drew on these earlier urban traditions. Many of their ancient cities continue to be inhabited, including major metropolitan cities such as Mexico City, in the same location as Tenochtitlan; while ancient continuously inhabited Pueblos are near modern urban areas in New Mexico, such as Acoma Pueblo near the Albuquerque metropolitan area and Taos Pueblo near Taos; while others like Lima are located nearby ancient Peruvian sites such as Pachacamac.

From 1600 BC, Dhar Tichitt, in the south of present-day Mauritania, presented characteristics suggestive of an incipient form of urbanism.[70][71] The second place to show urban characteristics in West Africa was Dia, in present-day Mali, from 800 BC.[70][71] Both Dhar Tichitt and Dia were founded by the same people: the Soninke, who would later also found the Ghana Empire.[71]

Another ancient site, Jenné-Jeno, in what is today Mali, has been dated to the third century BCE. According to Roderick and Susan McIntosh, Jenné-Jeno did not fit into traditional Western conceptions of urbanity as it lacked monumental architecture and a distinctive elite social class, but it should indeed be considered a city based on a functional redefinition of urban development. In particular, Jenné-Jeno featured settlement mounds arranged according to a horizontal, rather than vertical, power hierarchy, and served as a center of specialized production and exhibited functional interdependence with the surrounding hinterland.[72]

More recently, scholars have concluded that the civilization of Djenne-Djenno was likely established by the Mande progenitors of the Bozo people. Their habitation of the site spanned the period from 3rd century BCE to 13th century CE.[73] Archaeological evidence from Jenné-Jeno, specifically the presence of non-West African glass beads dated from the third century BCE to the fourth century CE, indicates that pre-Arabic trade contacts probably existed between Jenné-Jeno and North Africa.[74]

Additionally, other early urban centers in West Africa, dated to around 500 CE, include Awdaghust, Kumbi Saleh, the ancient capital of Ghana, and Maranda, a center located on a trade route between Egypt and Gao.[75]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The dissolution of the Roman Empire in the West was connected with profound changes in urban fabric of western Europe.[76] In places where Roman administration quickly weakened urbanism went through a profound crisis, even if it continued to remain an important symbolic factor.[77] In regions like Italy or Spain cities diminished in size but nevertheless continued to play a key role in both the economy and government.[78] Late antique cities in the East were also undergoing intense transformations, with increased political participation of the crowds and demographic fluctuations.[79] Christian communities and their doctrinal differences increasingly shaped the urban fabric.[80] The locus of power shifted to Constantinople and to the ascendant Islamic civilization with its major cities Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba.[81] From the 9th through the end of the 12th century, Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, with a population approaching 1 million.[82][83] The Ottoman Empire gradually gained control over many cities in the Mediterranean area, including Constantinople in 1453.

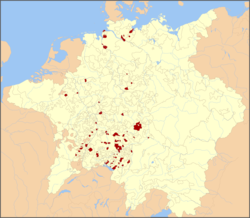

In the Holy Roman Empire, beginning in the 12th century, free imperial cities such as Nuremberg, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, Basel, Zürich, and Nijmegen became a privileged elite among towns having won self-governance from their local lord or having been granted self-governance by the emperor and being placed under his immediate protection. By 1480, these cities, as far as still part of the empire, became part of the Imperial Estates governing the empire with the emperor through the Imperial Diet.[84]

By the 13th and 14th centuries, some cities had become powerful states, taking surrounding areas under their control or establishing extensive maritime empires. In Italy, medieval communes developed into city-states including the Republic of Venice and the Republic of Genoa. In Northern Europe, cities including Lübeck and Bruges formed the Hanseatic League for collective defense and commerce. Their power was later challenged and eclipsed by the Dutch commercial cities of Ghent, Ypres, and Amsterdam.[85] Similar phenomena existed elsewhere, as in the case of Sakai, which enjoyed considerable autonomy in late medieval Japan.

In the first millennium AD, the Khmer capital of Angkor in Cambodia grew into the most extensive preindustrial settlement in the world by area,[86][87] covering over 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) and possibly supporting up to one million people.[86][88]

West Africa already had cities before the Common Era, but the consolidation of Trans-Saharan trade in the Middle Ages multiplied the number of cities in the region, as well as making some of them very populous, notably Gao (72,000 inhabitants in 800 AD), Oyo-Ile (50,000 inhabitants in 1400 AD, and may have reached up to 140,000 inhabitants in the 18th century), Ile-Ifẹ̀ (70,000 to 105,000 inhabitants in the 14th and 15th centuries), Niani (50,000 inhabitants in 1400 AD) and Timbuktu (100,000 inhabitants in 1450 AD).[70][89]

Early modern

[edit]In the West, nation-states became the dominant unit of political organization following the Peace of Westphalia in the seventeenth century.[90][91] Western Europe's larger capitals (London and Paris) benefited from the growth of commerce following the emergence of an Atlantic trade. However, most towns remained small.

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the old Roman city concept was extensively used. Cities were founded in the middle of the newly conquered territories and were bound to several laws regarding administration, finances, and urbanism.

Industrial age

[edit]The growth of the modern industry from the late 18th century onward led to massive urbanization and the rise of new great cities, first in Europe and then in other regions, as new opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban areas. England led the way as London became the capital of a world empire and cities across the country grew in locations strategic for manufacturing.[92] In the United States from 1860 to 1910, the introduction of railroads reduced transportation costs, and large manufacturing centers began to emerge, fueling migration from rural to city areas.

Some industrialized cities were confronted with health challenges associated with overcrowding, occupational hazards of industry, contaminated water and air, poor sanitation, and communicable diseases such as typhoid and cholera. Factories and slums emerged as regular features of the urban landscape.[93]

Post-industrial age

[edit]In the second half of the 20th century, deindustrialization (or "economic restructuring") in the West led to poverty, homelessness, and urban decay in formerly prosperous cities. America's "Steel Belt" became a "Rust Belt" and cities such as Detroit, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana began to shrink, contrary to the global trend of massive urban expansion.[94] Such cities have shifted with varying success into the service economy and public-private partnerships, with concomitant gentrification, uneven revitalization efforts, and selective cultural development.[95] Under the Great Leap Forward and subsequent five-year plans continuing today, China has undergone concomitant urbanization and industrialization and become the world's leading manufacturer.[96][97]

Amidst these economic changes, high technology and instantaneous telecommunication enable select cities to become centers of the knowledge economy.[98][99][100] A new smart city paradigm, supported by institutions such as the RAND Corporation and IBM, is bringing computerized surveillance, data analysis, and governance to bear on cities and city dwellers.[101] Some companies are building brand-new master-planned cities from scratch on greenfield sites.

Urbanization

[edit]

Urbanization is the process of migration from rural to urban areas, driven by various political, economic, and cultural factors. Until the 18th century, an equilibrium existed between the rural agricultural population and towns featuring markets and small-scale manufacturing.[103][104] With the agricultural and industrial revolutions, urban population began its unprecedented growth, both through migration and demographic expansion. In England, the proportion of the population living in cities jumped from 17% in 1801 to 72% in 1891.[105] In 1900, 15% of the world's population lived in cities.[106] The cultural appeal of cities also plays a role in attracting residents.[107]

Urbanization rapidly spread across Europe and the Americas and since the 1950s has taken hold in Asia and Africa as well. The Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs reported in 2014 that for the first time, more than half of the world population lives in cities.[108][a]

Latin America is the most urban continent, with four-fifths of its population living in cities, including one-fifth of the population said to live in shantytowns (favelas, poblaciones callampas, etc.).[115] Batam, Indonesia, Mogadishu, Somalia, Xiamen, China, and Niamey, Niger, are considered among the world's fastest-growing cities, with annual growth rates of 5–8%.[116] In general, the more developed countries of the "Global North" remain more urbanized than the less developed countries of the "Global South"—but the difference continues to shrink because urbanization is happening faster in the latter group. Asia is home to by far the greatest absolute number of city-dwellers: over two billion and counting.[104] The UN predicts an additional 2.5 billion city dwellers (and 300 million fewer country dwellers) worldwide by 2050, with 90% of urban population expansion occurring in Asia and Africa.[108][117]

Megacities, cities with populations in the multi-millions, have proliferated into the dozens, arising especially in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.[118][119] Economic globalization fuels the growth of these cities, as new torrents of foreign capital arrange for rapid industrialization, as well as the relocation of major businesses from Europe and North America, attracting immigrants from near and far.[120] A deep gulf divides the rich and poor in these cities, which usually contain a super-wealthy elite living in gated communities and large masses of people living in substandard housing with inadequate infrastructure and otherwise poor conditions.[121]

Cities around the world have expanded physically as they grow in population, with increases in their surface extent, with the creation of high-rise buildings for residential and commercial use, and with development underground.[122][123]

Urbanization can create rapid demand for water resources management, as formerly good sources of freshwater become overused and polluted, and the volume of sewage begins to exceed manageable levels.[124]

Government

[edit]

The local government of cities takes different forms including prominently the municipality (especially in England, in the United States, India, and former British colonies; legally, the municipal corporation;[125] municipio in Spain and Portugal, and, along with municipalidad, in most former parts of the Spanish and Portuguese empires) and the commune (in France and Chile; or comune in Italy).

The chief official of the city is very often called the "mayor". Whatever their true degree of political authority, the mayor typically acts as the figurehead or personification of their city.[126]

Legal conflicts and issues arise more frequently in cities than elsewhere due to the bare fact of their greater density.[127] Modern city governments thoroughly regulate everyday life in many dimensions, including public and personal health, transport, burial, resource use and extraction, recreation, and the nature and use of buildings. Technologies, techniques, and laws governing these areas—developed in cities—have become ubiquitous in many areas.[128] Municipal officials may be appointed from a higher level of government or elected locally.[129]

Municipal services

[edit]

Cities typically provide municipal services such as education, through school systems; policing, through police departments; and firefighting, through fire departments; as well as the city's basic infrastructure. These are provided more or less routinely, in a more or less equal fashion.[130][131] Responsibility for administration usually falls on the city government, but some services may be operated by a higher level of government,[132] while others may be privately run.[133] Armies may assume responsibility for policing cities in states of domestic turmoil such as America's King assassination riots of 1968.

Finance

[edit]The traditional basis for municipal finance is local property tax levied on real estate within the city. Local government can also collect revenue for services, or by leasing land that it owns.[134] However, financing municipal services, as well as urban renewal and other development projects, is a perennial problem, which cities address through appeals to higher governments, arrangements with the private sector, and techniques such as privatization (selling services into the private sector), corporatization (formation of quasi-private municipally owned corporations), and financialization (packaging city assets into tradeable financial public contracts and other related rights). This situation has become acute in deindustrialized cities and in cases where businesses and wealthier citizens have moved outside of city limits and therefore beyond the reach of taxation.[135][136][137][138] Cities in search of ready cash increasingly resort to the municipal bond, essentially a loan with interest and a repayment date.[139] City governments have also begun to use tax increment financing, in which a development project is financed by loans based on future tax revenues which it is expected to yield.[138] Under these circumstances, creditors and consequently city governments place a high importance on city credit ratings.[140]

Governance

[edit]

Governance includes government but refers to a wider domain of social control functions implemented by many actors including non-governmental organizations.[141] The impact of globalization and the role of multinational corporations in local governments worldwide have led to a shift in perspective on urban governance, away from the "urban regime theory" in which a coalition of local interests functionally govern, toward a theory of outside economic control, widely associated in academics with the philosophy of neoliberalism.[142] In the neoliberal model of governance, public utilities are privatized, the industry is deregulated, and corporations gain the status of governing actors—as indicated by the power they wield in public-private partnerships and over business improvement districts, and in the expectation of self-regulation through corporate social responsibility. The biggest investors and real estate developers act as the city's de facto urban planners.[143]

The related concept of good governance places more emphasis on the state, with the purpose of assessing urban governments for their suitability for development assistance.[144] The concepts of governance and good governance are especially invoked in emergent megacities, where international organizations consider existing governments inadequate for their large populations.[145]

Urban planning

[edit]

Urban planning, the application of forethought to city design, involves optimizing land use, transportation, utilities, and other basic systems in order to achieve certain objectives. Urban planners and scholars have proposed overlapping theories as ideals of how plans should be formed. Planning tools, beyond the original design of the city itself, include public capital investment in infrastructure and land-use controls such as zoning. The continuous process of comprehensive planning involves identifying general objectives as well as collecting data to evaluate progress and inform future decisions.[147][148]

Government is legally the final authority on planning but in practice, the process involves both public and private elements. The legal principle of eminent domain is used by the government to divest citizens of their property in cases where its use is required for a project.[148] Planning often involves tradeoffs—decisions in which some stand to gain and some to lose—and thus is closely connected to the prevailing political situation.[149]

The history of urban planning dates back to some of the earliest known cities, especially in the Indus Valley and Mesoamerican civilizations, which built their cities on grids and apparently zoned different areas for different purposes.[15][150] The effects of planning, ubiquitous in today's world, can be seen most clearly in the layout of planned communities, fully designed prior to construction, often with consideration for interlocking physical, economic, and cultural systems.

Society

[edit]Social structure

[edit]Urban society is typically stratified. Spatially, cities are formally or informally segregated along ethnic, economic, and racial lines. People living relatively close together may live, work, and play in separate areas, and associate with different people, forming ethnic or lifestyle enclaves or, in areas of concentrated poverty, ghettoes. While in the US and elsewhere poverty became associated with the inner city, in France it has become associated with the banlieues, areas of urban development that surround the city proper. Meanwhile, across Europe and North America, the racially white majority is empirically the most segregated group. Suburbs in the West, and, increasingly, gated communities and other forms of "privatopia" around the world, allow local elites to self-segregate into secure and exclusive neighborhoods.[151]

Landless urban workers, contrasted with peasants and known as the proletariat, form a growing stratum of society in the age of urbanization. In Marxist doctrine, the proletariat will inevitably revolt against the bourgeoisie as their ranks swell with disenfranchised and disaffected people lacking all stake[clarification needed] in the status quo.[152] The global urban proletariat of today, however, generally lacks the status of factory workers which in the nineteenth century provided access to the means of production.[153]

Economics

[edit]

Historically, cities rely on rural areas for intensive farming to yield surplus crops, in exchange for which they provide money, political administration, manufactured goods, and culture.[26][27] Urban economics tends to analyze larger agglomerations, stretching beyond city limits, in order to reach a more complete understanding of the local labor market.[154]

As hubs of trade, cities have long been home to retail commerce and consumption through the interface of shopping. In the 20th century, department stores using new techniques of advertising, public relations, decoration, and design, transformed urban shopping areas into fantasy worlds encouraging self-expression and escape through consumerism.[155][156]

In general, the density of cities expedites commerce and facilitates knowledge spillovers, helping people and firms exchange information and generate new ideas.[157][158] A thicker labor market allows for better skill matching between firms and individuals. Population density also enables sharing of common infrastructure and production facilities; however, in very dense cities, increased crowding and waiting times may lead to some negative effects.[159]

Although manufacturing fueled the growth of cities, many now rely on a tertiary or service economy. The services in question range from tourism, hospitality, entertainment, and housekeeping to grey-collar work in law, financial consulting, and administration.[95][160]

According to a scientific model of cities by Professor Geoffrey West, with the doubling of a city's size, salaries per capita will generally increase by 15%.[161]

Culture and communications

[edit]

Cities are typically hubs for education and the arts, supporting universities, museums, temples, and other cultural institutions.[163] They feature impressive displays of architecture ranging from small to enormous and ornate to brutal; skyscrapers, providing thousands of offices or homes within a small footprint, and visible from miles away, have become iconic urban features.[164] Cultural elites tend to live in cities, bound together by shared cultural capital, and themselves play some role in governance.[165] By virtue of their status as centers of culture and literacy, cities can be described as the locus of civilization, human history, and social change.[166][167]

Density makes for effective mass communication and transmission of news, through heralds, printed proclamations, newspapers, and digital media. These communication networks, though still using cities as hubs, penetrate extensively into all populated areas. In the age of rapid communication and transportation, commentators have described urban culture as nearly ubiquitous[168][169][170] or as no longer meaningful.[171]

Today, a city's promotion of its cultural activities dovetails with place branding and city marketing, public diplomacy techniques used to inform development strategy; attract businesses, investors, residents, and tourists; and create shared identity and sense of place within the metropolitan area.[172][173][174][175] Physical inscriptions, plaques, and monuments on display physically transmit a historical context for urban places.[176] Some cities, such as Jerusalem, Mecca, and Rome have indelible religious status and for hundreds of years have attracted pilgrims. Patriotic tourists visit Agra to see the Taj Mahal, or New York City to visit the World Trade Center. Elvis lovers visit Memphis to pay their respects at Graceland.[177] Place brands (which include place satisfaction and place loyalty) have great economic value (comparable to the value of commodity brands) because of their influence on the decision-making process of people thinking about doing business in—"purchasing" (the brand of)—a city.[175]

Bread and circuses among other forms of cultural appeal, attract and entertain the masses.[107][178] Sports also play a major role in city branding and local identity formation.[179] Cities go to considerable lengths in competing to host the Olympic Games, which bring global attention and tourism.[180] Paris, a city known for its cultural history, was the site of the most recent Olympics in the summer of 2024.[181]

Warfare

[edit]

Cities play a crucial strategic role in warfare due to their economic, demographic, symbolic, and political centrality. For the same reasons, they are targets in asymmetric warfare. Many cities throughout history were founded under military auspices, a great many have incorporated fortifications, and military principles continue to influence urban design.[182] Indeed, war may have served as the social rationale and economic basis for the very earliest cities.[49][50]

Powers engaged in geopolitical conflict have established fortified settlements as part of military strategies, as in the case of garrison towns, America's Strategic Hamlet Program during the Vietnam War, and Israeli settlements in Palestine.[183] While occupying the Philippines, the US Army ordered local people to concentrate in cities and towns, in order to isolate committed insurgents and battle freely against them in the countryside.[184][185]

During World War II, national governments on occasion declared certain cities open, effectively surrendering them to an advancing enemy in order to avoid damage and bloodshed. Urban warfare proved decisive, however, in the Battle of Stalingrad, where Soviet forces repulsed German occupiers, with extreme casualties and destruction. In an era of low-intensity conflict and rapid urbanization, cities have become sites of long-term conflict waged both by foreign occupiers and by local governments against insurgency.[153][186] Such warfare, known as counterinsurgency, involves techniques of surveillance and psychological warfare as well as close combat,[187] and functionally extends modern urban crime prevention, which already uses concepts such as defensible space.[188]

Although capture is the more common objective, warfare has in some cases spelled complete destruction for a city. Mesopotamian tablets and ruins attest to such destruction,[189] as does the Latin motto Carthago delenda est.[190][191] Since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and throughout the Cold War, nuclear strategists continued to contemplate the use of "counter-value" targeting: crippling an enemy by annihilating its valuable cities, rather than aiming primarily at its military forces.[192][193]

Climate change

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Climate change and society |

|---|

Infrastructure

[edit]

Urban infrastructure involves various physical networks and spaces necessary for transportation, water use, energy, recreation, and public functions.[206] Infrastructure carries a high initial cost in fixed capital but lower marginal costs and thus positive economies of scale.[207] Because of the higher barriers to entry, these networks have been classified as natural monopolies, meaning that economic logic favors control of each network by a single organization, public or private.[124][208]

Infrastructure in general plays a vital role in a city's capacity for economic activity and expansion, underpinning the very survival of the city's inhabitants, as well as technological, commercial, industrial, and social activities.[206][207] Structurally, many infrastructure systems take the form of networks with redundant links and multiple pathways, so that the system as a whole continues to operate even if parts of it fail.[208] The particulars of a city's infrastructure systems have historical path dependence because new development must build from what exists already.[207]

Megaprojects such as the construction of airports, power plants, and railways require large upfront investments and thus tend to require funding from the national government or the private sector.[209][208] Privatization may also extend to all levels of infrastructure construction and maintenance.[210]

Urban infrastructure ideally serves all residents equally but in practice may prove uneven—with, in some cities, clear first-class and second-class alternatives.[211][212][124]

Utilities

[edit]

Public utilities (literally, useful things with general availability) include basic and essential infrastructure networks, chiefly concerned with the supply of water, electricity, and telecommunications capability to the populace.[213]

Sanitation, necessary for good health in crowded conditions, requires water supply and waste management as well as individual hygiene. Urban water systems include principally a water supply network and a network (sewerage system) for sewage and stormwater. Historically, either local governments or private companies have administered urban water supply, with a tendency toward government water supply in the 20th century and a tendency toward private operation at the turn of the twenty-first.[124][b] The market for private water services is dominated by two French companies, Veolia Water (formerly Vivendi) and Engie (formerly Suez), said to hold 70% of all water contracts worldwide.[124][215]

Modern urban life relies heavily on the energy transmitted through electricity for the operation of electric machines (from household appliances to industrial machines to now-ubiquitous electronic systems used in communications, business, and government) and for traffic lights, street lights, and indoor lighting. Cities rely to a lesser extent on hydrocarbon fuels such as gasoline and natural gas for transportation, heating, and cooking. Telecommunications infrastructure such as telephone lines and coaxial cables also traverse cities, forming dense networks for mass and point-to-point communications.[216]

Transportation

[edit]

Because cities rely on specialization and an economic system based on wage labor, their inhabitants must have the ability to regularly travel between home, work, commerce, and entertainment.[217] City dwellers travel by foot or by wheel on roads and walkways, or use special rapid transit systems based on underground, overground, and elevated rail. Cities also rely on long-distance transportation (truck, rail, and airplane) for economic connections with other cities and rural areas.[218]

City streets historically were the domain of horses and their riders and pedestrians, who only sometimes had sidewalks and special walking areas reserved for them.[219] In the West, bicycles or (velocipedes), efficient human-powered machines for short- and medium-distance travel,[220] enjoyed a period of popularity at the beginning of the twentieth century before the rise of automobiles.[221] Soon after, they gained a more lasting foothold in Asian and African cities under European influence.[222] In Western cities, industrializing, electrifying, and expanding public transit systems, especially streetcars, enabled urban expansion as new residential neighborhoods sprang up along transit lines and workers rode to and from work downtown.[218][223]

Since the mid-20th century, cities have relied heavily on motor vehicle transportation, with major implications for their layout, environment, and aesthetics.[224] (This transformation occurred most dramatically in the US—where corporate and governmental policies favored automobile transport systems—and to a lesser extent in Europe.)[218][223] The rise of personal cars accompanied the expansion of urban economic areas into much larger metropolises, subsequently creating ubiquitous traffic issues with the accompanying construction of new highways, wider streets, and alternative walkways for pedestrians.[225][226][227][173] However, severe traffic jams still occur regularly in cities around the world, as private car ownership and urbanization continue to increase, overwhelming existing urban street networks.[134]

The urban bus system, the world's most common form of public transport, uses a network of scheduled routes to move people through the city, alongside cars, on the roads.[228] The economic function itself also became more decentralized as concentration became impractical and employers relocated to more car-friendly locations (including edge cities).[218] Some cities have introduced bus rapid transit systems which include exclusive bus lanes and other methods for prioritizing bus traffic over private cars.[134][229] Many big American cities still operate conventional public transit by rail, as exemplified by the ever-popular New York City Subway system. Rapid transit is widely used in Europe and has increased in Latin America and Asia.[134]

Walking and cycling ("non-motorized transport") enjoy increasing favor (more pedestrian zones and bike lanes) in American and Asian urban transportation planning, under the influence of such trends as the Healthy Cities movement, the drive for sustainable development, and the idea of a carfree city.[134][230][231] Techniques such as road space rationing and road use charges have been introduced to limit urban car traffic.[134]

Housing

[edit]

The housing of residents presents one of the major challenges every city must face. Adequate housing entails not only physical shelters but also the physical systems necessary to sustain life and economic activity.[232]

Homeownership represents status and a modicum of economic security, compared to renting which may consume much of the income of low-wage urban workers. Homelessness, or lack of housing, is a challenge currently faced by millions of people in countries rich and poor.[233] Because cities generally have higher population densities than rural areas, city dwellers are more likely to reside in apartments and less likely to live in a single-family home.

Ecology

[edit]

Urban ecosystems, influenced as they are by the density of human buildings and activities, differ considerably from those of their rural surroundings. Anthropogenic buildings and waste, as well as cultivation in gardens, create physical and chemical environments which have no equivalents in the wilderness, in some cases enabling exceptional biodiversity. They provide homes not only for immigrant humans but also for immigrant plants, bringing about interactions between species that never previously encountered each other. They introduce frequent disturbances (construction, walking) to plant and animal habitats, creating opportunities for recolonization and thus favoring young ecosystems with r-selected species dominant. On the whole, urban ecosystems are less complex and productive than others, due to the diminished absolute amount of biological interactions.[234][235][236][237]

Typical urban fauna includes insects (especially ants), rodents (mice, rats), and birds, as well as cats and dogs (domesticated and feral). Large predators are scarce.[236] However, in North America, large predators such as coyotes and other large animals like white-tailed deer persist.[238]

Cities generate considerable ecological footprints, locally and at longer distances, due to concentrated populations and technological activities. From one perspective, cities are not ecologically sustainable due to their resource needs. From another, proper management may be able to ameliorate a city's ill effects.[239][240] Air pollution arises from various forms of combustion,[241] including fireplaces, wood or coal-burning stoves, other heating systems,[242] and internal combustion engines. Industrialized cities, and today third-world megacities, are notorious for veils of smog (industrial haze) that envelop them, posing a chronic threat to the health of their millions of inhabitants.[243] Urban soil contains higher concentrations of heavy metals (especially lead, copper, and nickel) and has lower pH than soil in the comparable wilderness.[236]

Modern cities are known for creating their own microclimates, due to concrete, asphalt, and other artificial surfaces, which heat up in sunlight and channel rainwater into underground ducts. The temperature in New York City exceeds nearby rural temperatures by an average of 2–3 °C and at times 5–10 °C differences have been recorded. This effect varies nonlinearly with population changes (independently of the city's physical size).[236][244] Aerial particulates increase rainfall by 5–10%. Thus, urban areas experience unique climates, with earlier flowering and later leaf dropping than in nearby countries.[236]

Poor and working-class people face disproportionate exposure to environmental risks (known as environmental racism when intersecting also with racial segregation). For example, within the urban microclimate, less-vegetated poor neighborhoods bear more of the heat (but have fewer means of coping with it).[245]

One of the main methods of improving the urban ecology is including in the cities more urban green spaces: parks, gardens, lawns, and trees. These areas improve the health and well-being of the human, animal, and plant populations of the cities.[246] Well-maintained urban trees can provide many social, ecological, and physical benefits to the residents of the city.[247]

A study published in Scientific Reports in 2019 found that people who spent at least two hours per week in nature were 23 percent more likely to be satisfied with their life and were 59 percent more likely to be in good health than those who had zero exposure. The study used data from almost 20,000 people in the UK. Benefits increased for up to 300 minutes of exposure. The benefits are applied to men and women of all ages, as well as across different ethnicities, socioeconomic statuses, and even those with long-term illnesses and disabilities. People who did not get at least two hours – even if they surpassed an hour per week – did not get the benefits. The study is the latest addition to a compelling body of evidence for the health benefits of nature. Many doctors already give nature prescriptions to their patients. The study did not count time spent in a person's own yard or garden as time in nature, but the majority of nature visits in the study took place within two miles of home. "Even visiting local urban green spaces seems to be a good thing," Dr. White said in a press release. "Two hours a week is hopefully a realistic target for many people, especially given that it can be spread over an entire week to get the benefit."[248]

World city system

[edit]As the world becomes more closely linked through economics, politics, technology, and culture (a process called globalization), cities have come to play a leading role in transnational affairs, exceeding the limitations of international relations conducted by national governments.[249][250][251] This phenomenon, resurgent today, can be traced back to the Silk Road, Phoenicia, and the Greek city-states, through the Hanseatic League and other alliances of cities.[252][253][254] Today the information economy based on high-speed internet infrastructure enables instantaneous telecommunication around the world, effectively eliminating the distance between cities for the purposes of the international markets and other high-level elements of the world economy, as well as personal communications and mass media.[255]

Global city

[edit]

A global city, also known as a world city, is a prominent centre of trade, banking, finance, innovation, and markets.[256][257] Saskia Sassen used the term "global city" in her 1991 work, The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo to refer to a city's power, status, and cosmopolitanism, rather than to its size.[258] Following this view of cities, it is possible to rank the world's cities hierarchically.[259] Global cities form the capstone of the global hierarchy, exerting command and control through their economic and political influence. Global cities may have reached their status due to early transition to post-industrialism[260] or through inertia which has enabled them to maintain their dominance from the industrial era.[261] This type of ranking exemplifies an emerging discourse in which cities, considered variations on the same ideal type, must compete with each other globally to achieve prosperity.[180][173]

Critics of the notion point to the different realms of power and interchange. The term "global city" is heavily influenced by economic factors and, thus, may not account for places that are otherwise significant. Paul James, for example argues that the term is "reductive and skewed" in its focus on financial systems.[262]

Multinational corporations and banks make their headquarters in global cities and conduct much of their business within this context.[263] American firms dominate the international markets for law and engineering and maintain branches in the biggest foreign global cities.[264]

Large cities have a great divide between populations of both ends of the financial spectrum.[265] Regulations on immigration promote the exploitation of low- and high-skilled immigrant workers from poor areas.[266][267][268] During employment, migrant workers may be subject to unfair working conditions, including working overtime, low wages, and lack of safety in workplaces.[269]

Transnational activity

[edit]Cities increasingly participate in world political activities independently of their enclosing nation-states. Early examples of this phenomenon are the sister city relationship and the promotion of multi-level governance within the European Union as a technique for European integration.[250][270][271] Cities including Hamburg, Prague, Amsterdam, The Hague, and City of London maintain their own embassies to the European Union at Brussels.[272][273][274]

New urban dwellers are increasingly transmigrants, keeping one foot each (through telecommunications if not travel) in their old and their new homes.[275]

Global governance

[edit]Cities participate in global governance by various means including membership in global networks which transmit norms and regulations. At the general, global level, United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) is a significant umbrella organization for cities; regionally and nationally, Eurocities, Asian Network of Major Cities 21, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities the National League of Cities, and the United States Conference of Mayors play similar roles.[276][277] UCLG took responsibility for creating Agenda 21 for culture, a program for cultural policies promoting sustainable development, and has organized various conferences and reports for its furtherance.[278]

Networks have become especially prevalent in the arena of environmentalism and specifically climate change following the adoption of Agenda 21. Environmental city networks include the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, the United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme, the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance (CNCA), the Covenant of Mayors and the Compact of Mayors,[279] ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, and the Transition Towns network.[276][277]

Cities hold world political status as meeting places for advocacy groups, non-governmental organizations, lobbyists, educational institutions, intelligence agencies, military contractors, information technology firms, and other groups with a stake in world policymaking. They are consequently also sites for symbolic protest.[253][c]

South Africa has one of the highest rates of protests in the world. Pretoria, a city in South Africa, had a rally where five thousand people took part in order to advocate for increasing wages to afford living costs.[280]

United Nations System

[edit]

The United Nations System has been involved in a series of events and declarations dealing with the development of cities during this period of rapid urbanization.

- The Habitat I conference in 1976 adopted the "Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements" which identifies urban management as a fundamental aspect of development and establishes various principles for maintaining urban habitats.[281]

- Citing the Vancouver Declaration, the UN General Assembly in December 1977 authorized the United Nations Commission Human Settlements and the HABITAT Centre for Human Settlements, intended to coordinate UN activities related to housing and settlements.[282]

- The 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro resulted in a set of international agreements including Agenda 21 which establishes principles and plans for sustainable development.[283]

- The Habitat II conference in 1996 called for cities to play a leading role in this program, which subsequently advanced the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals.[284]

- In January 2002 the UN Commission on Human Settlements became an umbrella agency called the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or UN-Habitat, a member of the United Nations Development Group.[282]

- The Habitat III conference of 2016 focused on implementing these goals under the banner of a "New Urban Agenda". The four mechanisms envisioned for effecting the New Urban Agenda are (1) national policies promoting integrated sustainable development, (2) stronger urban governance, (3) long-term integrated urban and territorial planning, and (4) effective financing frameworks.[285][286] Just before this conference, the European Union concurrently approved an "Urban Agenda for the European Union" known as the Pact of Amsterdam.[285]

UN-Habitat coordinates the U.N. urban agenda, working with the UN Environmental Programme, the UN Development Programme, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the World Health Organization, and the World Bank.[282]

The World Bank, a U.N. specialized agency, has been a primary force in promoting the Habitat conferences, and since the first Habitat conference has used their declarations as a framework for issuing loans for urban infrastructure.[284] The bank's structural adjustment programs contributed to urbanization in the Third World by creating incentives to move to cities.[287][288] The World Bank and UN-Habitat in 1999 jointly established the Cities Alliance (based at the World Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C.) to guide policymaking, knowledge sharing, and grant distribution around the issue of urban poverty.[289] (UN-Habitat plays an advisory role in evaluating the quality of a locality's governance.)[144] The Bank's policies have tended to focus on bolstering real estate markets through credit and technical assistance.[290]

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has increasingly focused on cities as key sites for influencing cultural governance. It has developed various city networks including the International Coalition of Cities against Racism and the Creative Cities Network. UNESCO's capacity to select World Heritage Sites gives the organization significant influence over cultural capital, tourism, and historic preservation funding.[278]

Representation in culture

[edit]

Cities figure prominently in traditional Western culture, appearing in the Bible in both evil and holy forms, symbolized by Babylon and Jerusalem.[291] Cain and Nimrod are the first city builders in the Book of Genesis. In Sumerian mythology Gilgamesh built the walls of Uruk.

Cities can be perceived in terms of extremes or opposites: at once liberating and oppressive, wealthy and poor, organized and chaotic.[292] The name anti-urbanism refers to various types of ideological opposition to cities, whether because of their culture or their political relationship with the country. Such opposition may result from identification of cities with oppression and the ruling elite.[293] This and other political ideologies strongly influence narratives and themes in discourse about cities.[14] In turn, cities symbolize their home societies.[294]

Writers, painters, and filmmakers have produced innumerable works of art concerning the urban experience. Classical and medieval literature includes a genre of descriptiones which treat of city features and history. Modern authors such as Charles Dickens and James Joyce are famous for evocative descriptions of their home cities.[295] Fritz Lang conceived the idea for his influential 1927 film Metropolis while visiting Times Square and marveling at the nighttime neon lighting.[296] Other early cinematic representations of cities in the twentieth century generally depicted them as technologically efficient spaces with smoothly functioning systems of automobile transport. By the 1960s, however, traffic congestion began to appear in such films as The Fast Lady (1962) and Playtime (1967).[224]

Literature, film, and other forms of popular culture have supplied visions of future cities both utopian and dystopian. The prospect of expanding, communicating, and increasingly interdependent world cities has given rise to images such as Nylonkong (New York, London, Hong Kong)[297] and visions of a single world-encompassing ecumenopolis.[298]

Gallery

[edit]-

Map of Piraeus, designed according to the Hippodameian grid plan

-

Warsaw Old Town after the Warsaw uprising with 85% of the city destroyed

-

Central Park in New York City

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Intellectuals such as H. G. Wells, Patrick Geddes and Kingsley Davis foretold the coming of a mostly urban world throughout the twentieth century.[109][110] The United Nations has long anticipated a half-urban world, earlier predicting the year 2000 as the turning point[111][112] and in 2007 writing that it would occur in 2008.[113] Other researchers had also estimated that the halfway point was reached in 2007.[114] Although the trend is undeniable, the precision of this statistic is dubious, due to reliance on national censuses and to the ambiguities of defining an area as urban.[109][9]

- ^ Water resources in rapidly urbanizing areas are not merely privatized as they are in western countries; since the systems do not exist to begin with, private contracts also entail water industrialization and enclosure.[124] Also, there is a countervailing trend: 100 cities have re-municipalized their water supply since the 1990s.[214]

- ^ One important global political city, described at one time as a world capital, is Washington, D.C. and its metropolitan area, including Tysons and Reston in the Dulles Technology Corridor and the various federal agencies found along the Baltimore–Washington Parkway). Beyond the prominent institutions of U.S. government on the national mall, this area contains 177 embassies, The Pentagon, the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters, the World Bank headquarters, myriad think tanks and lobbying groups, and corporate headquarters for Booz Allen Hamilton, General Dynamics, Capital One, Verisign, Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, and Gannett Company.[253]

References

[edit]- ^ Goodall, B. (1987). The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography. London: Penguin.

- ^ Kuper, A.; Kuper, J., eds. (1996). The Social Science Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 99.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (13 June 2018). "Urbanization". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-76574-7. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Cities: a 'cause of and solution to' climate change". UN News. 18 September 2019. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Sustainable cities must be compact and high-density". The Guardian. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Table 6 Archived 11 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine" in United Nations Demographic Yearbook (2015 Archived 8 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine), the 1988 version of which is quoted in Carter (1995), pp. 10–12.

- ^ a b c Hugo, Graeme; Champion, Anthony; Lattes, Alfredo. "Toward a New Conceptualization of Settlements for Demography Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine", Population and Development Review 29(2), June 2003.

- ^ "How NC Municipalities Work – North Carolina League of Municipalities". nclm.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Population by region – Urban population by city size – OECD Data". theOECD. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Moholy-Nagy (1968), p. 45.

- ^ a b "city, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, June 2014.

- ^ a b Lynch, Kevin A., "What Is the Form of a City, and How Is It Made?"; in Marzluff et al. (2008), p. 678. "The city may be looked on as a story, a pattern of relations between human groups, a production and distribution space, a field of physical force, a set of linked decisions, or an arena of conflict. Values are embedded in these metaphors: historic continuity, stable equilibrium, productive efficiency, capable decision and management, maximum interaction, or the progress of political struggle. Certain actors become the decisive elements of transformation in each view: political leaders, families and ethnic groups, major investors, the technicians of transport, the decision elite, the revolutionary classes."

- ^ a b c d Smith, "Earliest Cities Archived 29 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine", in Gmelch & Zenner (2002).

- ^ Marshall (1989), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Prokopovych, M. (13 May 2015). Literary and artistic metropolises. EGO. Retrieved 5 March 2023, from http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/crossroads/courts-and-cities/markian-prokopovych-rosemary-h-sweet-literary-and-artistic-metropolises

- ^ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Dijkstra, Lewis; Hamilton, Ellen; Lall, Somik; Wahba, Sameh (10 March 2020). "How do we define cities, towns, and rural areas?". Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Moore, Oliver (2 October 2021). "What makes a city a city? It's a little complicated". The Globe and Mail. p. A11.

- ^ Jianping, Yi (2012). ""Civilization" and "State": An Etymological Perspective". Social Sciences in China. 33 (2): 181–197. doi:10.1080/02529203.2012.677292. ISSN 0252-9203.

- ^ Room 1996, p. 13.

- ^ Carter (1995), pp. 5–7. "[...] the two main themes of study introduced at the outset: the town as a distributed feature and the town as a feature with internal structure, or in other words, the town in area and the town as area."

- ^ Bataille, L., "From passive to energy generating assets", Energy in Buildings & Industry, October 2021 Archived 12 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 34. Retrieved 12 February 2022

- ^ Marshall (1989), pp. 11–14.

- ^ a b Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Marshall (1989), p. 15. "The mutual interdependence of town and country has one consequence so obvious that it is easily overlooked: at the global scale, cities are generally confined to areas capable of supporting a permanent agricultural population. Moreover, within any area possessing a broadly uniform level of agricultural productivity, there is a rough but definite association between the density of the rural population and the average spacing of cities above any chosen minimum size."

- ^ a b Latham et al. 2009, p. 18: "From the simplest forms of exchange, when peasant farmers literally brought their produce from the fields into the densest point of interaction—giving us market towns—the significance of central places to surrounding territories began to be asserted. As cities grew in complexity, the major civic institutions, from seats of government to religious buildings, would also come to dominate these points of convergence. Large central squares or open spaces reflected the importance of collective gatherings in city life, such as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the Zócalo in Mexico City, the Piazza Navonae in Rome and Trafalgar Square in London."

- ^ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 34–35. "In the center of the city, an elite compound or temenos was situated. Study of the very earliest cities show this compound to be largely composed of a temple and supporting structures. The temple rose some 40 feet above the ground and would have presented a formidable profile to those far away. The temple contained the priestly class, scribes, and record keepers, as well as granaries, schools, crafts—almost all non-agricultural aspects of society."

- ^ Latham et al. 2009, pp. 177–179.

- ^ Mitchell, Don (1995). "The End of Public Space?People's Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy" (PDF). Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 85 (1): 108–133. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1995.tb01797.xa (inactive 6 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link)[permanent dead link] - ^ Li, Xiaoma; Zhou, Weiqi (1 May 2019). "Optimizing urban greenspace spatial pattern to mitigate urban heat island effects: Extending understanding from local to the city scale". Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 41: 255–263. Bibcode:2019UFUG...41..255L. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.04.008. ISSN 1618-8667. S2CID 149962822.

- ^ Moholy-Nagy (1968), 21–33.

- ^ Pant, Mohan; Fumo, Shjui (2005). "The Grid and Modular Measures in The Town Planning of Mohenjodaro and Kathmandu Valley. A Study on Modular Measures in Block and Plot Divisions in the Planning of Mohenjodaro and Sirkap (Pakistan), and Thimi (Kathmandu Valley)". Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering. 59 (4): 51–59. doi:10.3130/jaabe.4.51.

- ^ Danino, Matthew (2008). "New Insights into Harappan Town-Planning, Proportions and Units, with Special Reference to Dholavira" (PDF). Man and Environment. 33 (1): 66–79. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017.

- ^ Jane McIntosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives; ABC-CLIO, 2008; ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2 pp. 231 Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 346 Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Carter (1995), p. 15. "In the underbound city the administratively defined area is smaller than the physical extent of settlement. In the overbound city the administrative area is greater than the physical extent. The 'truebound' city is one where the administrative bound is nearly coincidental with the physical extent."

- ^ Paul James; Meg Holden; Mary Lewin; Lyndsay Neilson; Christine Oakley; Art Truter; David Wilmoth (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Harald Mieg; Klaus Töpfer (eds.). Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development. Routledge. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Fang, Chuanglin; Yu, Danlin (2017). "Urban agglomeration: An evolving concept of an emerging phenomenon". Landscape and Urban Planning. 162: 126–136. Bibcode:2017LUrbP.162..126F. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.02.014.

- ^ Mazzucato, Camilla (9 May 2019). "Socio-Material Archaeological Networks at Çatalhöyük a Community Detection Approach". Frontiers in Digital Humanities. 6 8. doi:10.3389/fdigh.2019.00008. ISSN 2297-2668.

- ^ "10 oldest cities in the world". EducationWorld. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Nick Compton, "What is the oldest city in the world?", The Guardian, 16 February 2015.

- ^ (Bairoch 1988, pp. 3–4)

- ^ (Pacione 2001, p. 16)

- ^ Kaplan et al. (2004), p. 26. "Early cities also reflected these preconditions in that they served as places where agricultural surpluses were stored and distributed. Cities functioned economically as centers of extraction and redistribution from countryside to granaries to the urban population. One of the main functions of this central authority was to extract, store, and redistribute the grain. It is no accident that granaries—storage areas for grain—were often found within the temples of early cities."

- ^ Pournelle, Jennifer R. (31 December 2007). "KLM to Corona: A Bird's Eye View of Cultural Ecology and Early Mesopotamian Urbanization". In Elizabeth C. Stone (ed.). Settlement and Society: Essays Dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, and Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 29–62. doi:10.2307/j.ctvdjrqjp.8. ISBN 978-1-938770-97-5.

- ^ a b Perlman, Fredy, Against His-Story, Against Leviathan, Detroit: Black & Red, 1983; p. 16.

- ^ a b Mumford (1961), pp. 39–46. "As the physical means increased, this one-sided power mythology, sterile, indeed hostile to life, pushed its way into every corner of the urban scene and found, in the new institution of organized war, its completest expression. [...] Thus both the physical form and the institutional life of the city, from the very beginning to the urban implosion, were shaped in no small measure by the irrational and magical purposes of war. From this source sprang the elaborate system of fortifications, with walls, ramparts, towers, canals, ditches, that continued to characterize the chief historic cities, apart from certain special cases—as during the Pax Romana—down to the eighteenth century. [...] War brought concentration of social leadership and political power in the hands of a weapons-bearing minority, abetted by a priesthood exercising sacred powers and possessing secret but valuable scientific and magical knowledge."

- ^ a b Ashworth (1991), pp. 12–13.

- ^ (Jacobs 1969, p. 23)

- ^ Taylor, Peter J. (2012). "Extraordinary Cities: Early 'City-ness' and the Origins of Agriculture and States". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 36 (3): 415–447. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01101.x. hdl:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01101.x. ISSN 0309-1317.; see also GaWC Research Bulletins 359 Archived 11 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine and 360 Archived 13 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Smith, Michael E.; Ur, Jason; Feinman, Gary M. (2014). "Jane Jacobs' 'Cities First' Model and Archaeological Reality". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 38 (4): 1525–1535. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12138. ISSN 0309-1317. S2CID 143207540. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 October 2017.

- ^ McQuillan (1937/1987), §1.03. "The ancients fostered the spread of urban culture; their efforts were constant to bring their people within the complete influence of municipal life. The desire to create cities was the most striking characteristic of the people of antiquity, and ancient rulers and statesmen vied with one another in satisfying that desire."

- ^ Southall (1998), p. 23.

- ^ Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art (October 2003). "Uruk: The First City". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Uruk (article)". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "What Science Has Learned about the Rise of Urban Mesopotamia". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Ring, Trudy (2014). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-134-25986-1.

- ^ Pandeyl, Jhimli Mukherjee (25 February 2016). "Varanasi is as old as Indus valley civilization, finds IIT-KGP study". The Times of India.

- ^ "Where was the first city in the world?". New Scientist. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1998). Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization (2nd ed.). Karachi and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577940-0.

- ^ Southall (1998), pp. 38–43.

- ^ Moholy-Nagy (1968), pp. 158–161.

- ^ Adams, Robert McCormick (1981). Heartland of cities: surveys of ancient settlement and land use on the central floodplain of the Euphrates (PDF). Chicago and London: University of Chicago press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-226-00544-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2018.

Southern Mesopotamia was a land of cities. It became one precociously, before the end of the fourth millennium B.C. Urban traditions remained strong and virtually continuous through the vicissitudes of conquest, internal upheaval accompanied by widespread economic breakdown, and massive linguistic and population replacement. The symbolic and material content of civilization obviously changed, but its cultural ambience remained tied to cities.

- ^ Pocock, J.G.A. (1998). The Citizenship Debates. Chapter 2 – The Ideal of Citizenship since Classical Times (originally published in Queen's Quarterly 99, no. 1). Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8166-2880-3. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2015.