Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dromotropic

View on Wikipedia

The term dromotropic derives from the Greek word δρόμος drómos, meaning "running", a course, a race. A dromotropic agent is one which affects the conduction speed (in fact the magnitude of delay[1]) in the AV node, and subsequently the rate of electrical impulses in the heart.[2][3]

Positive dromotropy increases conduction velocity (e.g. epinephrine stimulation), negative dromotropy decreases velocity (e.g. vagal stimulation).[4]

Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers such as verapamil block the slow inward calcium current in cardiac tissues, thereby having a negatively dromotropic, chronotropic and inotropic effect.[5] This (and other) pharmacological effect makes these drugs useful in the treatment of angina pectoris. Conversely, they can lead to symptomatic disturbances in cardiac conduction and bradyarrhythmias, and may aggravate left ventricular failure.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ ""AV node; the magnitude of the delay" - Google Search". www.Google.ca. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Furukawa, Y.; Wallick, D. W.; Martin, P. J.; Levy, M. N. (1 May 1990). "Chronotropic and dromotropic responses to stimulation of intracardiac sympathetic nerves to sinoatrial or atrioventricular nodal region in anesthetized dogs". Circulation Research. 66 (5): 1391–1399. doi:10.1161/01.RES.66.5.1391. PMID 2335032.

- ^ Dromotropic Archived 2017-04-10 at the Wayback Machine at eMedicine Dictionary

- ^ RPh, Shafinewaz. "Toronto Notes for Medical Students Essential Med Notes 2016". Retrieved 14 April 2019 – via www.Academia.edu.

- ^ "eTG complete". HCN.net.au. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ "AccessMedicine - Harrison's Internal Medicine: Stable Angina Pectoris". 27 September 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

Dromotropic

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Background

Definition

Dromotropic refers to the physiological effect that modulates the velocity of electrical impulse conduction through the heart's specialized conduction pathways, particularly the atrioventricular (AV) node, where impulses are typically delayed to allow atrial contraction before ventricular activation.[5] This modulation can accelerate or decelerate conduction speed, influencing the timing of ventricular depolarization without primarily altering other cardiac parameters.[6] In contrast to chronotropic effects, which adjust heart rate by acting on the sinoatrial node's pacemaker activity, or inotropic effects, which change the force of myocardial contraction, dromotropic effects specifically target conduction velocity to affect impulse propagation, potentially leading to changes in atrioventricular synchrony.[5] Positive dromotropy enhances conduction speed, while negative dromotropy slows it, often via autonomic nervous system influences or pharmacological agents.[2] The term "dromotropic" was introduced in 1897 by German physiologist Theodor Wilhelm Engelmann in his seminal paper on the myogenic origin of heart activity and automatic excitability in peripheral nerve fibers.[7]Etymology

The term "dromotropic" derives from the Greek "dromos" (δρόμος), meaning "running," "course," or "race," combined with the suffix "-tropic," from "tropos" (τρόπος), denoting "turning" or "affecting." This etymological structure reflects an influence on the pathway or velocity of signal transmission, particularly in physiological contexts like nerve or muscle conduction.[8][9] The adjective "dromotropic" first appeared in scientific literature in the 1890s, with its earliest documented use in 1895–1897 by German physiologist Theodor Wilhelm Engelmann in studies on frog heart innervation. Engelmann coined the term alongside related descriptors—chronotropic (affecting rate or timing), inotropic (affecting contractility), and bathmotropic (affecting excitability)—to classify the distinct actions of cardiac nerves on heart function.80106-9/fulltext)[10] Within autonomic pharmacology, "dromotropic" evolved as part of this "-tropic" nomenclature family, standardizing descriptions of sympathetic and parasympathetic effects on cardiac electrophysiology. This framework, originating from Engelmann's work, persists in modern terminology to denote agents or stimuli modulating conduction speed without altering rate or force directly.[11]Physiological Role

Cardiac Conduction System Basics

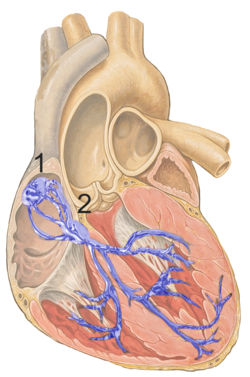

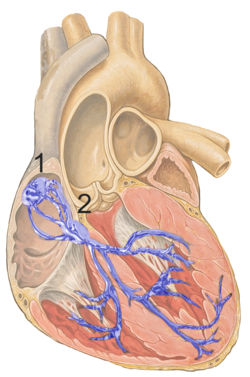

The cardiac conduction system is a specialized network of modified cardiac muscle cells that generates electrical impulses and coordinates the sequential contraction of the heart's chambers to ensure efficient blood flow. This system includes four primary components: the sinoatrial (SA) node, atrioventricular (AV) node, bundle of His, and Purkinje fibers, each with distinct anatomical locations and roles in impulse initiation and propagation. The SA node, situated in the upper wall of the right atrium near the entrance of the superior vena cava, serves as the heart's primary pacemaker by spontaneously generating action potentials at a rate of 60 to 100 beats per minute under normal conditions. These impulses rapidly spread through the atrial myocardium, causing atrial contraction.[12][13] The electrical impulse then reaches the AV node, located near the center of the heart at the junction of the atria and ventricles, where conduction slows significantly to allow complete atrial emptying before ventricular activation. This AV nodal delay lasts approximately 0.1 seconds (100 milliseconds), preventing premature ventricular contraction and optimizing cardiac output. From the AV node, the impulse travels via the bundle of His—a collection of fibers extending along the interventricular septum—to the left and right bundle branches, which distribute the signal to the ventricular walls. The Purkinje fibers, branching extensively within the endocardium of the ventricles, enable rapid and synchronized depolarization of the ventricular myocardium, ensuring a coordinated "bottom-up" contraction that efficiently pumps blood to the body and lungs. Overall, the impulse travels from the atria to the ventricles in approximately 0.1 to 0.2 seconds, as reflected in the normal PR interval on an electrocardiogram.[14][15][12] At the electrophysiological level, conduction within the cardiac system relies on action potentials generated by voltage-gated ion channels in specialized cells, which vary in speed across components due to differences in channel types and densities. In non-pacemaker cells like those in the atria, ventricles, and Purkinje fibers (fast-response cells), the action potential consists of five phases: phase 0 involves rapid depolarization driven by influx of sodium ions (Na⁺) through fast voltage-gated Na⁺ channels, achieving conduction velocities up to 4 meters per second in Purkinje fibers; phase 1 is a brief early repolarization from transient potassium (K⁺) efflux; phase 2 maintains a prolonged plateau via calcium (Ca²⁺) influx through L-type Ca²⁺ channels balanced against K⁺ efflux; phase 3 completes repolarization through dominant K⁺ efflux; and phase 4 maintains a stable resting potential around -90 mV primarily due to high K⁺ conductance. In contrast, slow-response cells in the SA and AV nodes rely more on Ca²⁺ channels for phase 0 depolarization, resulting in slower conduction (about 0.05 to 0.5 meters per second) and the characteristic delays essential for timed contractions; phase 4 in these pacemaker cells features spontaneous depolarization via "funny" currents (I_f, involving slow Na⁺ influx) and T-type Ca²⁺ channels, setting the rhythm. These ion channel dynamics underpin the variable conduction speeds that synchronize heart function, with dromotropic effects modulating them through autonomic influences.[16][14][17]Mechanism of Dromotropic Effects

Dromotropic effects refer to modifications in the velocity of electrical impulse conduction through the cardiac conduction system, primarily influencing the atrioventricular (AV) node and His-Purkinje system. Positive dromotropic effects accelerate conduction, particularly by shortening the refractory period and AV nodal delay, thereby facilitating faster propagation of impulses from atria to ventricles.[1] In contrast, negative dromotropic effects decelerate conduction, prolonging the AV delay and potentially leading to incomplete or blocked impulses at the AV node.[1] The AV node exhibits slow conduction velocity due to its reliance on L-type calcium channels for phase 0 depolarization of the action potential, where calcium influx (supplemented by some sodium through slow channels) drives the upstroke. Negative dromotropic effects slow AV nodal conduction by reducing L-type calcium channel activity, which diminishes inward calcium current and prolongs the action potential duration.[18] Conversely, in the His-Purkinje system, fast conduction is mediated by voltage-gated fast sodium channels responsible for rapid phase 0 depolarization; acceleration here occurs through enhanced sodium channel availability or function, increasing overall ventricular activation speed. Autonomic nervous system modulation plays a central role in these effects. Sympathetic stimulation via β1-adrenergic receptors activates adenylyl cyclase, elevating cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels and activating protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates L-type calcium channels in the AV node to enhance calcium influx and thereby increase conduction velocity (positive dromotropy).[1] Parasympathetic (vagal) stimulation, mediated by acetylcholine binding to M2 muscarinic receptors, couples to inhibitory G-proteins that decrease cAMP, inhibit PKA, and activate acetylcholine-sensitive potassium channels (K_ACh), leading to membrane hyperpolarization and reduced excitability, which slows AV nodal conduction (negative dromotropy).[1] These autonomic influences ensure adaptive regulation of conduction in response to physiological demands.[19]Pharmacological and Clinical Aspects

Positive Dromotropic Agents

Positive dromotropic agents are pharmacological substances that accelerate the velocity of electrical impulse conduction within the cardiac conduction system, primarily by enhancing atrioventricular (AV) nodal transmission.[20] These agents counteract excessive vagal tone or stimulate sympathetic pathways to improve conduction efficiency, which is crucial in conditions involving slowed heart rhythms.[21] Sympathomimetic agents such as isoproterenol exemplify positive dromotropic effects through beta-1 adrenergic receptor agonism, which increases calcium influx and shortens the A-H interval (a measure of AV nodal conduction time) in isolated heart preparations.[22] Isoproterenol reduces AV nodal delay by facilitating faster impulse propagation across the node, thereby enhancing overall cardiac excitability.[22] Similarly, atropine exerts a positive dromotropic action via competitive muscarinic receptor blockade, diminishing parasympathetic inhibition on the AV node and thereby accelerating conduction velocity.[23] This blockade reduces vagally mediated delays in AV transmission, promoting more rapid sinoatrial to ventricular signal relay.[21] Endogenous catecholamines, including epinephrine and norepinephrine, play a key role in positive dromotropy during acute stress responses. Released from the adrenal medulla and sympathetic nerve endings, these agents activate beta-1 receptors to elevate conduction speed, ensuring synchronized cardiac output under physiological demands like fight-or-flight scenarios.[20] Their effects integrate with broader sympathetic activation to maintain efficient AV nodal function amid heightened adrenergic tone.[4] In therapeutic contexts, these agents are employed to manage bradyarrhythmias by restoring adequate conduction rates. For instance, intravenous atropine typically onset within 1-2 minutes, rapidly alleviating AV nodal blocks associated with vagal overactivity.[21] Isoproterenol infusion similarly supports conduction in acute settings, though its use requires careful monitoring due to potent beta-adrenergic stimulation.[24]Negative Dromotropic Agents

Negative dromotropic agents are substances that decrease the velocity of electrical impulse conduction through the cardiac conduction system, primarily by prolonging the refractory period or slowing depolarization in specific tissues. Physiologically, increased vagal tone serves as a natural negative dromotrope, particularly during rest, where parasympathetic stimulation inhibits AV nodal conduction via acetylcholine-mediated hyperpolarization of nodal cells.[25][23] Among pharmacological agents, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers such as verapamil and diltiazem exemplify negative dromotropic effects by selectively inhibiting L-type calcium channels in the AV node, thereby reducing the slow inward calcium current essential for nodal depolarization. This action prolongs the AV nodal refractory period, slowing conduction and preventing rapid impulse transmission from atria to ventricles.[26][27] Digoxin exerts negative dromotropic effects primarily by enhancing parasympathetic (vagal) tone on the AV node, which slows conduction velocity and prolongs the refractory period.[28] Adenosine produces a potent, transient negative dromotropic effect by activating A1 adenosine receptors in the AV node, leading to hyperpolarization and temporary blockade of conduction.[29] Class I antiarrhythmics, including flecainide, exert negative dromotropic influence on the His-Purkinje system through use-dependent blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels, which markedly slows conduction velocity in fast-response Purkinje fibers and prolongs the HV interval.[30][31] Beta-blockers like propranolol, a non-selective agent, contribute to negative dromotropy by antagonizing β-adrenergic receptors, thereby reducing sympathetic enhancement of nodal and His-Purkinje conduction and slowing impulse propagation.[32][33] In opposition to positive dromotropic agents that accelerate conduction, these negative agents are crucial for modulating excessive impulse transmission in various cardiac conditions.Clinical Significance

Role in Arrhythmias

Dromotropic imbalances play a critical role in the pathogenesis of atrioventricular (AV) blocks, where negative dromotropy slows conduction through the AV node, leading to delayed or blocked impulse transmission. In first-degree AV block, conduction delay manifests as a prolonged PR interval exceeding 200 ms on electrocardiogram (ECG), resulting from impaired AV nodal propagation due to factors exerting negative dromotropic effects.[34][35] This prolongation reflects a subtle but consistent slowing of atrial-to-ventricular impulse conduction, often without symptoms but serving as an early indicator of dromotropic dysfunction.[36] More severe negative dromotropy can progress to second-degree AV block, characterized by intermittent failure of atrial impulses to conduct to the ventricles, as seen in Mobitz type I (Wenckebach) where progressive PR interval lengthening culminates in a dropped beat. Adenosine, for instance, induces this block by slowing AV nodal recovery of excitability, creating discontinuous propagation across junctional tissues.[18] In third-degree (complete) AV block, extreme negative dromotropic effects cause total dissociation between atrial and ventricular rhythms, with no conduction through the AV node, leading to independent ventricular escape rhythms. Agents like diazepam can precipitate this by gradually prolonging the PR interval until complete block occurs.[37] Conversely, in tachyarrhythmias such as those associated with Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, enhanced dromotropy via accessory pathways facilitates rapid conduction that bypasses the normal AV nodal delay, predisposing to re-entrant circuits and supraventricular tachycardias. These pathways allow early ventricular activation, shortening the PR interval to less than 120 ms on ECG and producing a delta wave, which indicates accelerated atrioventricular transmission.[36][38] This abnormal fast conduction enables atrial impulses to reach the ventricles prematurely, increasing the risk of rapid ventricular rates during atrial fibrillation.[38] ECG assessment of PR interval variations provides key diagnostic metrics for dromotropic dysfunction in arrhythmias; prolongation signals negative effects in AV blocks, while shortening highlights enhanced conduction in pre-excitation syndromes like WPW. These changes directly correlate with conduction velocity alterations, aiding in the identification of underlying dromotropic imbalances without invasive testing in many cases.[34][36]Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications

Dromotropic modulation plays a key role in managing cardiac rhythm disorders through pharmacological interventions that alter atrioventricular (AV) nodal conduction velocity. Negative dromotropic agents, such as calcium channel blockers like verapamil, are commonly employed for rate control in atrial fibrillation (AF) by slowing AV nodal conduction and reducing ventricular response rates. For instance, intravenous verapamil effectively controls heart rates in most patients with AF, achieving significant reductions in ventricular rates, often by 20-40% from baseline rapid rates exceeding 120 beats per minute.[39] Beta-blockers and digoxin also serve as negative dromotropic options for similar purposes in AF, helping to prevent tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy by maintaining controlled ventricular rates.[40] Positive dromotropic agents are utilized to treat symptomatic bradycardia by enhancing AV nodal conduction. Atropine, a vagolytic agent, is a first-line pharmacological option in advanced cardiac life support protocols for bradydysrhythmias, increasing conduction velocity through parasympathetic inhibition.[41] Isoproterenol, a beta-adrenergic agonist, provides positive dromotropic effects by stimulating AV nodal pathways, making it suitable for temporary management of bradycardia unresponsive to atropine, with dosing titrated to achieve desired heart rates.[24] In cases refractory to pharmacological therapy, invasive procedures target dromotropic pathways directly. AV nodal ablation is a palliative strategy for drug-resistant AF, particularly in patients with heart failure, where it interrupts AV conduction to enforce rate control via subsequent pacemaker implantation, preferably using conduction system pacing techniques such as His-bundle or left bundle branch pacing to optimize synchrony and outcomes as of 2024, leading to improved symptoms, quality of life, and modest ejection fraction gains of 4-7% in those with systolic dysfunction.[42][43] Pacemaker implantation is indicated for persistent bradycardia due to irreversible negative dromotropy or iatrogenic causes, such as drug-induced AV block, ensuring reliable ventricular pacing when pharmacological restoration fails.[44] Diagnostic applications of dromotropic assessment involve electrophysiology studies (EPS) to evaluate AV nodal function precisely. During EPS, the AH interval—measuring conduction time from the atrium to the His bundle—quantifies AV nodal dromotropy, with prolongation or jumps exceeding 50 ms indicating dual pathways or conduction delays relevant to arrhythmias like AV nodal reentrant tachycardia.[45] Catheter-based mapping in EPS guides targeted interventions by identifying sites of abnormal conduction velocity, aiding in the diagnosis of bradycardias and planning ablations.[46]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dromotropic