Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Franklin Pierce

View on Wikipedia

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804 – October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to national unity, he alienated anti-slavery groups by signing the Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act. Conflict between North and South continued after Pierce's presidency, and, following Abraham Lincoln's victory in the 1860 presidential election, the Southern states seceded, resulting in the American Civil War.

Key Information

Pierce was born in New Hampshire; his father was state governor Benjamin Pierce. He served in the House of Representatives from 1833 until his election to the Senate, where he served from 1837 until his resignation in 1842. His private law practice was a success, and he was appointed New Hampshire's U.S. attorney in 1845. Pierce took part in the Mexican–American War as a brigadier general in the United States Army. Democrats saw him as a compromise candidate uniting Northern and Southern interests, and nominated him for president at the 1852 Democratic National Convention. He and running mate William R. King easily defeated the Whig Party ticket of Winfield Scott and William Alexander Graham in the 1852 presidential election.

As president, Pierce attempted to enforce neutral standards for civil service while also satisfying the Democratic Party's diverse elements with patronage, an effort that largely failed and turned many in his party against him. He was a Young America expansionist who signed the Gadsden Purchase of land from Mexico and led a failed attempt to acquire Cuba from Spain. He signed trade treaties with Britain and Japan and his Cabinet reformed its departments and improved accountability, but political strife during his presidency overshadowed these successes. His popularity declined sharply in the Northern states after he supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which nullified the Missouri Compromise, while many Southern whites continued to support him. The act's passage led to violent conflict over the expansion of slavery in the American West. Pierce's administration was further damaged when several of his diplomats issued the Ostend Manifesto calling for the annexation of Cuba, a document that was roundly criticized. He fully expected the Democrats to renominate him in the 1856 presidential election, but they abandoned him and his bid failed. His reputation in the North suffered further during the American Civil War as he became a vocal critic of President Lincoln.

While Pierce was popular and outgoing, his family life was difficult; his three children died young, and his wife, Jane Pierce, suffered from illness and depression for much of her life.[1] Their last surviving son was killed in a train accident while the family was traveling, shortly before Pierce's inauguration. A heavy drinker for much of his life, Pierce died in 1869 of cirrhosis. As a result of his support of the South, as well as failing to hold the Union together in time of strife, historians and scholars generally rank Pierce as one of the worst[2][3] and least memorable U.S. presidents.[4]

Early life and family

[edit]Childhood and education

[edit]

Franklin Pierce was born on November 23, 1804, in a log cabin in Hillsborough, New Hampshire. He was a sixth-generation descendant of Thomas Pierce, who had moved to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from Norwich, Norfolk, England, in about 1634. His father Benjamin was a lieutenant in the American Revolutionary War who moved from Chelmsford, Massachusetts, to Hillsborough after the war, purchasing 50 acres (20 ha) of land. Pierce was the fifth of eight children born to Benjamin and his second wife Anna Kendrick; his first wife Elizabeth Andrews died in childbirth, leaving a daughter. Benjamin was a prominent Democratic-Republican[note 3] state legislator, farmer, and tavern-keeper. During Pierce's childhood, his father was deeply involved in state politics, while two of his older brothers fought in the War of 1812; public affairs and the military were thus a major influence in his early life.[8]

Pierce's father placed Pierce in a school at Hillsborough Center in childhood and sent him to the town school in Hancock at age 12.[note 4] Not fond of schooling, Pierce grew homesick and walked 12 miles (19 km) back to his home one Sunday. His father fed him dinner and drove him part of the distance back to school before ordering him to walk the rest of the way in a thunderstorm. Pierce later cited this moment as "the turning-point in my life".[10] Later that year, he transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy to prepare for college. By this time, he had built a reputation as a charming student, sometimes prone to misbehavior.[10]

In fall 1820, Pierce entered Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, one of 19 freshmen. He joined the Athenian Society, a progressive literary society, alongside Jonathan Cilley (later elected to Congress) and Nathaniel Hawthorne, with whom he formed lasting friendships. He was the last in his class after two years, but he worked hard to improve his grades and graduated in fifth place in 1824[12] in a graduating class of 14.[13] John P. Hale enrolled at Bowdoin in Pierce's junior year; he became a political ally of Pierce's and then his rival. Pierce organized and led an unofficial militia company called the Bowdoin Cadets during his junior year, which included Cilley and Hawthorne. The unit performed drill on campus near the president's house, until the noise caused him to demand that it halt. The students rebelled and went on strike, an event that Pierce was suspected of leading.[14] During his final year at Bowdoin, he spent several months teaching at Hebron Academy in rural Hebron, Maine, where he earned his first salary and his students included future Congressman John J. Perry.[15][16]

Pierce read law briefly with former New Hampshire Governor Levi Woodbury, a family friend in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[17] He then spent a semester at Northampton Law School in Northampton, Massachusetts, followed by a period of study in 1826 and 1827 under Judge Edmund Parker in Amherst, New Hampshire. He was admitted to the New Hampshire bar in late 1827 and began to practice in Hillsborough.[18] He lost his first case, but soon proved capable as a lawyer. Despite never being a legal scholar, his memory for names and faces served him well, as did his personal charm and deep voice.[19] In Hillsborough, his law partner was Albert Baker, who had studied law under Pierce and was the brother of Mary Baker Eddy.[20]

Hillsborough and state politics

[edit]By 1824, New Hampshire was a hotbed of partisanship, with figures such as Woodbury and Isaac Hill laying the groundwork for a party of Democrats in support of General Andrew Jackson. They opposed the established Federalists (and their successors, the National Republicans), who were led by sitting President John Quincy Adams. The work of the New Hampshire Democratic Party came to fruition in March 1827, when their pro-Jackson nominee, Benjamin Pierce, won the support of the pro-Adams faction and was elected governor of New Hampshire essentially unopposed. While the younger Pierce had set out to build a career as an attorney, he was fully drawn into the realm of politics as the 1828 presidential election between Adams and Jackson approached. In the state elections held in March 1828, the Adams faction withdrew their support of Benjamin Pierce, voting him out of office,[note 5] but Franklin Pierce won his first election, a one-year term as Hillsborough's town meeting moderator, a position to which he was reelected five times.[21]

Pierce actively campaigned in his district on behalf of Jackson, who carried both the district and the nation by large margins in the November 1828 election, even though he lost New Hampshire. The outcome further strengthened the Democratic Party, and Pierce won his first legislative seat the following year, representing Hillsborough in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. Pierce's father was elected again as governor, retiring after that term. The younger Pierce was appointed as chairman of the House Education Committee in 1829 and the Committee on Towns the following year. By 1831 the Democrats held a legislative majority, and Pierce was elected Speaker of the House. The young Speaker used his platform to oppose the expansion of banking, protect the state militia, and offer support to the national Democrats and Jackson's reelection effort. At 27, he was a star of the New Hampshire Democratic Party. Though attaining early political and professional success, in his personal letters he continued to lament his bachelorhood and yearned for a life beyond Hillsborough.[22]

Like all white males in New Hampshire between the ages of 18 and 45, Pierce was a member of the state militia, and was appointed aide de camp to Governor Samuel Dinsmoor in 1831. He remained in the militia until 1847, and attained the rank of colonel before becoming a brigadier general in the Army during the Mexican–American War.[23][24] Interested in revitalizing and reforming the state militias, which had become increasingly dormant during the years of peace following the War of 1812, Pierce worked with Alden Partridge, president of Norwich University, a military college in Vermont, and Truman B. Ransom and Alonzo Jackman, Norwich faculty members and militia officers, to increase recruiting efforts and improve training and readiness.[25][26] Pierce served as a Norwich University trustee from 1841 to 1859, and received the honorary degree of LL.D. from Norwich in 1853.[27]

In late 1832, the Democratic Party convention nominated Pierce for one of New Hampshire's five seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. This was tantamount to election for the young Democrat, as the National Republicans had faded as a political force, while the Whigs had not yet begun to attract a large following. Democratic strength in New Hampshire was also bolstered by Jackson's landslide reelection that year.[28] New Hampshire had been a marginal state politically, but from 1832 through the mid-1850s became the most reliably Democratic state in the Northern United States, boosting Pierce's political career.[29] Pierce's term began in March 1833, but he would not be sworn in until Congress met in December, and his attention was elsewhere. He had recently become engaged and bought his first house in Hillsborough. Franklin and Benjamin Pierce were among the prominent citizens who welcomed President Jackson to the state on his visit in mid-1833.[28]

Marriage and children

[edit]

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton, a daughter of Congregational minister Jesse Appleton and Elizabeth Means. The Appletons were prominent Whigs, in contrast with the Pierces' Democratic affiliation. Jane Pierce was shy, devoutly religious, and pro-temperance, encouraging Pierce to abstain from alcohol. She was somewhat gaunt, and constantly ill from tuberculosis and psychological ailments. She abhorred politics and especially disliked Washington, D.C., creating a tension that would continue throughout Pierce's political ascent.[30][31][32]

Jane Pierce disliked Hillsborough as well, and in 1838, the Pierces relocated to the state capital, Concord, New Hampshire.[33] They had three sons, all of whom died in childhood. Franklin Jr. (February 2–5, 1836) died in infancy, while Frank Robert (August 27, 1839 – November 14, 1843) died at the age of four from epidemic typhus. Benjamin (April 13, 1841 – January 6, 1853) died at the age of 11 in a train accident.[34]

Congressional career

[edit]U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]Pierce departed in November 1833 for Washington, D.C., where the Twenty-third United States Congress convened its regular session on December 2. Jackson's second term was under way, and the House of Representatives had a strong Democratic majority, whose primary focus was to prevent the Second Bank of the United States from being rechartered. The Democrats, including Pierce, defeated proposals supported by the newly formed Whig Party, and the bank's charter expired. Pierce broke from his party on occasion, opposing Democratic bills to fund internal improvements with federal money. He saw both the bank and infrastructure spending as unconstitutional, with internal improvements the responsibility of the states. Pierce's first term was fairly uneventful from a legislative standpoint, and he was easily reelected in March 1835. When not in Washington, he attended to his law practice, and in December 1835 returned to the capital for the Twenty-fourth Congress.[35]

As abolitionism grew more vocal in the mid-1830s, Congress was inundated with petitions from anti-slavery groups seeking legislation to restrict slavery in the United States. From the beginning, Pierce found the abolitionists' "agitation" to be an annoyance, and saw federal action against slavery as an infringement on southern states' rights, even though he was morally opposed to slavery itself.[36] He was also frustrated with the "religious bigotry" of abolitionists, who cast their political opponents as sinners.[37] "I consider slavery a social and political evil," Pierce said, "and most sincerely wish that it had no existence upon the face of the earth."[38] Still, he wrote in December 1835, "One thing must be perfectly apparent to every intelligent man. This abolition movement must be crushed or there is an end to the Union."[39] After the Civil War, Pierce believed that if the North had not aggressively agitated against Southern slavery, the South would have eventually ended slavery on its own and that the conflict had been "brought upon the nation by fanatics on both sides".[40]

When Rep. James Henry Hammond of South Carolina looked to prevent anti-slavery petitions from reaching the House floor, however, Pierce sided with the abolitionists' right to petition. Nevertheless, Pierce supported what came to be known as the gag rule, which allowed for petitions to be received, but not read or considered. This passed the House in 1836.[36] He was attacked by the New Hampshire anti-slavery Herald of Freedom as a "doughface", which had the dual meaning of "craven-spirited man" and "northerner with southern sympathies".[41] Pierce had stated that not one in 500 New Hampshirites were abolitionists; the Herald of Freedom article added up the number of signatures on petitions from that state, divided by the number of residents according to the 1830 census, and suggested the actual number was one-in-33. Pierce was outraged when South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun read the article on the Senate floor as "proof" that New Hampshire was a hotbed of abolitionism. Calhoun apologized after Pierce replied to him in a speech which stated that most signatories were women and children, who could not vote, which therefore cast doubt on the one-in-33 figure.[42]

U.S. Senate

[edit]

The resignation in May 1836 of Senator Isaac Hill, who had been elected governor of New Hampshire, left a short-term opening to be filled by the state legislature, and with Hill's term as senator due to expire in March 1837, the legislature also had to fill the six-year term to follow. Pierce's candidacy for the Senate was championed by state Representative John P. Hale, a fellow Athenian at Bowdoin. After much debate, the legislature chose John Page to fill the rest of Hill's term. In December 1836, Pierce was elected to the full term, to commence in March 1837, and at age 32, was at the time one of the youngest members in Senate history. The election came at a difficult time for Pierce, as his father, sister, and brother were all seriously ill, while his wife also continued to suffer from chronic poor health. As senator, he was able to help his old friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, who often struggled financially, procuring for him a sinecure as measurer of coal and salt at the Boston Customs House that allowed the author time to continue writing.[43]

Pierce voted the party line on most issues and was an able senator, but not an eminent one; he was overshadowed by the Great Triumvirate of Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster, who dominated the Senate.[44] Pierce entered the Senate at a time of economic crisis, as the Panic of 1837 had begun. He considered the depression a result of the banking system's rapid growth, amidst "the extravagance of overtrading and the wilderness of speculation".[45] So that federal money would not support speculative bank loans, he supported newly elected Democratic president Martin Van Buren and his plan to create an independent treasury, a proposal which split the Democratic Party. Debate over slavery continued in Congress, and abolitionists proposed its end in the District of Columbia, where Congress had jurisdiction. Pierce supported a resolution by Calhoun against this proposal, which Pierce considered a dangerous stepping stone to nationwide emancipation.[45] Meanwhile, the Whigs were growing in congressional strength, which would leave Pierce's party with only a small majority by the end of the decade.[46]

One topic of particular importance to Pierce was the military. He took an interest in military pensions, seeing abundant fraud within the system, and was named chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Pensions in the Twenty-sixth Congress (1839–1841). In that capacity, he urged the modernization and expansion of the Army, with a focus on militias and mobility rather than on coastal fortifications, which he considered outdated.[47]

Pierce campaigned vigorously throughout his home state for Van Buren's reelection in the 1840 presidential election. The incumbent carried New Hampshire but lost the election to the Whig candidate, military hero William Henry Harrison. The Whigs took a majority of seats in the Twenty-seventh Congress. Harrison died after a month in office, and Vice President John Tyler succeeded him. Pierce and the Democrats were quick to challenge the new administration, questioning the removal of federal officeholders, and opposing Whig plans for a national bank. In December 1841 Pierce decided to resign from Congress, something he had been planning for some time.[48] New Hampshire Democrats insisted that their state's U. S. senators be limited to one six-year term, so he had little likelihood of reelection. Also, he was frustrated at being a member of the legislative minority and wished to devote his time to his family and law practice.[49] His last actions in the Senate in February 1842 were to oppose a bill distributing federal funds to the states—believing that the money should go to the military instead—and to challenge the Whigs to reveal the results of their investigation of the New York Customs House, where the Whigs had probed for Democratic corruption for nearly a year but had issued no findings.[50]

Party leader

[edit]Lawyer and politician

[edit]

Despite his resignation from the Senate, Pierce had no intention of leaving public life. The move to Concord had given him more opportunities for cases, and allowed Jane Pierce a more robust community life.[52] Jane had remained in Concord with her young son Frank and her newborn Benjamin for the latter part of Pierce's Senate term, and this separation had taken a toll on the family. Pierce, meanwhile, had begun a demanding but lucrative law partnership with Asa Fowler during congressional recesses.[53] Pierce returned to Concord in early 1842, and his reputation as a lawyer continued to flourish. Known for his gracious personality, eloquence, and excellent memory, Pierce attracted large audiences in court. He would often represent poor people for little or no compensation.[54]

Pierce remained involved in the state Democratic Party, which was split by several issues. Governor Hill, who represented the commercial, urban wing of the party, advocated the use of government charters to support corporations, granting them privileges such as limited liability and eminent domain for building railroads. The radical "locofoco" wing of his party represented farmers and other rural voters, who sought an expansion of social programs and labor regulations and a restriction on corporate privilege. The state's political culture grew less tolerant of banks and corporations after the Panic of 1837, and Hill was voted out of office. Pierce was closer to the radicals philosophically, and reluctantly agreed to represent Hill's adversary in a legal dispute regarding ownership of a newspaper—Hill lost, and founded his own paper, of which Pierce was a frequent target.[55]

In June 1842 Pierce was named chairman of the State Democratic Committee, and in the following year's state election he helped the radical wing take over the state legislature. The party remained divided on several issues, including railroad development and the temperance movement, and Pierce took a leading role in helping the state legislature settle their differences. His priorities were "order, moderation, compromise, and party unity", which he tried to place ahead of his personal views on political issues.[56] As he would as president, Pierce valued Democratic Party unity highly, and saw the opposition to slavery as a threat to that.[57]

Democratic James K. Polk's dark horse victory in the 1844 presidential election was welcome news to Pierce, who had befriended the former Speaker of the House while both served in Congress. Pierce had campaigned heavily for Polk during the election, and in turn Polk appointed him as United States Attorney for New Hampshire.[58] Polk's most prominent cause was the annexation of Texas, an issue which caused a dramatic split between Pierce and his former ally Hale, now a U.S. Representative. Hale was so impassioned against adding a new slave state that he wrote a public letter to his constituents outlining his opposition to the measure.[59] Pierce responded by reassembling the state Democratic convention to revoke Hale's nomination for another term in Congress.[60] The political firestorm led to Pierce severing ties with his longtime friend, and with his law partner Fowler, who was a Hale supporter.[61] Hale refused to withdraw, and as a majority vote was needed for election in New Hampshire, the party split led to deadlock and a vacant House seat. Eventually, the Whigs and Hale's Independent Democrats took control of the legislature, elected Whig Anthony Colby as governor, and sent Hale to the Senate, much to Pierce's anger.[62]

Mexican–American War

[edit]

Active military service was a long-held dream for Pierce, who had admired his father's and brothers' service in his youth, particularly his older brother Benjamin's, as well as that of John McNeil Jr., husband of Pierce's older half-sister Elizabeth. As a legislator, he was a passionate advocate for volunteer militias. As a militia officer himself, he had experience mustering and drilling bodies of troops. When Congress declared war against Mexico in May 1846, Pierce immediately volunteered to join, although no New England regiment yet existed. His hope to fight in the Mexican–American War was one reason he refused an offer to become Polk's Attorney General. General Zachary Taylor's advance slowed in northern Mexico, and General Winfield Scott proposed capturing the port of Vera Cruz and driving overland to Mexico City. Congress passed a bill authorizing the creation of ten regiments, and Pierce was appointed commander and colonel of the 9th Infantry Regiment in February 1847, with Truman B. Ransom as lieutenant colonel and second-in-command.[63]

On March 3, 1847, Pierce was promoted to brigadier general, and took command of a brigade of reinforcements for General Scott's army, with Ransom succeeding to command of the regiment. Needing time to assemble his brigade, Pierce reached the already seized port of Vera Cruz in late June, where he prepared a march of 2,500 men accompanying supplies for Scott. The three-week journey inland was perilous, and the men fought off several attacks before joining with Scott's army in early August, in time for the Battle of Contreras.[65] The battle was disastrous for Pierce: his horse was suddenly startled during a charge, knocking him groin-first against his saddle. The horse then tripped into a crevice and fell, pinning Pierce underneath and debilitating his knee.[66] The incident made it look like he had fainted, causing one soldier to call for someone else to take command, saying, "General Pierce is a damned coward."[67] Pierce returned for the following day's action, but injured his knee again, forcing him to hobble after his men; by the time he caught up, the battle was mostly won.[67]

As the Battle of Churubusco approached, Scott ordered Pierce to the rear to convalesce. He responded, "For God's sake, General, this is the last great battle, and I must lead my brigade." Scott yielded, and Pierce entered the fight tied to his saddle, but the pain in his leg became so great that he passed out on the field. The Americans won the battle and Pierce helped negotiate an armistice. He then returned to command and led his brigade throughout the rest of the campaign, eventually taking part in the capture of Mexico City in mid-September, although his brigade was held in reserve for much of the battle.[68] For much of the Mexico City battle, he was in the sick tent, plagued by acute diarrhea.[67] Pierce remained in command of his brigade during the three-month occupation of the city; while frustrated by the stalled peace negotiations, he also tried to distance himself from the constant conflict between Scott and the other generals.[68]

Pierce was finally allowed to return to Concord in late December 1847. He was given a hero's welcome in his home state, and submitted his resignation from the Army, which was approved on March 20, 1848. His military exploits elevated his popularity in New Hampshire, but his injuries and subsequent troubles in battle led to accusations of cowardice that would long shadow him. He had demonstrated competence as a general, especially in the initial march from Vera Cruz, but his short tenure and his injury left little for historians to judge his ability as a military commander by.[64]

Ulysses S. Grant, who had the opportunity to observe Pierce firsthand during the war, countered the allegations of cowardice in his memoirs, written several years after Pierce's death: "Whatever General Pierce's qualifications may have been for the Presidency, he was a gentleman and a man of courage. I was not a supporter of him politically, but I knew him more intimately than I did any other of the volunteer generals."[69]

Return to New Hampshire

[edit]

Returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law practice; in one notable case he defended the religious liberty of the Shakers, the insular sect threatened with legal action over accusations of abuse. But his role as a party leader continued to take up most of his attention. He continued to wrangle with Hale, who was anti-slavery and had opposed the war, stances that Pierce regarded as needless agitation.[70]

The large Mexican Cession of land divided the U.S. politically, with many in the North insisting that slavery not be allowed there (and offering the Wilmot Proviso to ensure it), while others wanted slavery barred north of the Missouri Compromise line of 36°30′ N. Both proposals were anathema to many Southerners, and the controversy split the Democrats. At the 1848 Democratic National Convention, the majority nominated former Michigan senator Lewis Cass for president, while a minority broke off to become the Free Soil Party, backing former president Van Buren. The Whigs chose General Zachary Taylor, a Louisianan, whose views on most political issues were unknown. Despite his past support for Van Buren, Pierce supported Cass, turning down the quiet offer of second place on the Free Soil ticket, and was so effective that Taylor, who was elected president, was held in New Hampshire to his lowest percentage in any state.[71]

Senator Henry Clay, a Whig, hoped to put the slavery question to rest with a set of proposals that became known as the Compromise of 1850. These would give victories to North and South, and gained the support of his fellow Whig, Webster. With the bill stalled in the Senate, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas led a successful effort to split it into separate measures so that each legislator could vote against the parts his state opposed without endangering the overall package. The bills passed, and were signed by President Millard Fillmore (who had succeeded Taylor after the president's death earlier in 1850).[72] Pierce strongly supported the compromise, giving a well-received speech in December 1850 pledging himself to "The Union! Eternal Union!"[73] The same month, the Democratic nominee for governor, John Atwood, issued a letter opposing the Compromise, and Pierce helped to recall the state convention and remove Atwood from the ticket.[73] The fiasco compromised the election for the Democrats, who lost several races; still, Pierce's party retained its control over the state, and was well positioned for the upcoming presidential election.[74]

Election of 1852

[edit]

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided over slavery, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party with Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned. It was widely expected that the 1852 Democratic National Convention would deadlock, with no candidate able to win the necessary two-thirds majority. New Hampshire Democrats, including Pierce, supported his old teacher, Levi Woodbury, by then an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, as a compromise candidate, but Woodbury's death in September 1851 opened up an opportunity for Pierce's allies to present him as a potential dark horse in the mold of Polk. New Hampshire Democrats felt that, as the state in which their party had most consistently gained Democratic majorities, they should supply the presidential candidate. Other possible standard-bearers included Douglas, Cass, William Marcy of New York, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Sam Houston of Texas, and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.[75][76]

Despite home-state support, Pierce faced obstacles to his nomination, since he had been out of office for a decade, and lacked the front-runners' national reputation. He publicly declared that such a nomination would be "utterly repugnant to my tastes and wishes", but given New Hampshire Democrats' desire to see one of their own elected, he knew his future influence depended on his availability to run.[77] Thus, he quietly allowed his supporters to lobby for him, with the understanding that his name would not be entered at the convention unless it was clear that none of the front-runners could win. To broaden his potential base of southern support as the convention approached, he wrote letters reiterating his support for the Compromise of 1850, including the controversial Fugitive Slave Act.[77][78]

The convention assembled on June 1 in Baltimore, and deadlock occurred as expected. On the first ballot of the 288 delegates, held on June 3, Cass claimed 116, Buchanan 93, and the rest were scattered, with no votes for Pierce. The next 34 ballots passed with no candidate even close to victory, and still no votes for Pierce. Buchanan's team then had its delegates vote for minor candidates, including Pierce, to demonstrate Buchanan's inevitability and unite the convention behind him. This novel tactic backfired after several ballots as Virginia, New Hampshire, and Maine switched to Pierce; the remaining Buchanan forces began to break for Marcy, and Pierce was soon in third place. After the 48th ballot, North Carolina Congressman James C. Dobbin delivered an unexpected and passionate endorsement of Pierce, sparking a wave of support for him. On the 49th ballot, Pierce received all but six of the votes, gaining the nomination. Delegates selected Alabama Senator William R. King, a Buchanan supporter, as Pierce's running mate, and adopted a platform that rejected further "agitation" over slavery and supported the Compromise of 1850.[79][80]

When word reached New Hampshire of the result, Pierce found it difficult to believe, and his wife fainted. Their son Benjamin wrote to his mother hoping that Franklin's candidacy would not be successful, as he knew she would not like to live in Washington.[81]

The Whig nominee was General Scott, Pierce's commander in Mexico; his running mate was Secretary of the Navy William A. Graham. The Whigs could not unify their factions as the Democrats had, and the convention adopted a platform almost indistinguishable from the Democrats', including support of the Compromise of 1850. This incited the Free Soilers to field their own candidate, Senator Hale, at the Whigs' expense. The lack of political differences reduced the campaign to a bitter personality contest and helped to dampen voter turnout to its lowest level since 1836; according to biographer Peter A. Wallner, it was "one of the least exciting campaigns in presidential history".[82][83] Scott was harmed by the lack of enthusiasm of anti-slavery northern Whigs for him and the platform; New-York Tribune editor Horace Greeley summed up the attitude of many when he said of the Whig platform, "we defy it, execrate it, spit upon it".[84]

Pierce kept quiet so as not to upset his party's delicate unity, and allowed his allies to run the campaign. It was the custom at the time for candidates to not appear to seek the office, and he did no personal campaigning.[85][86][87] Pierce's opponents caricatured him as an anti-Catholic coward and alcoholic ("the hero of many a well-fought bottle").[88][86] Scott, meanwhile, drew weak support from the Whigs, who were torn by their pro-Compromise platform and found him to be an abysmal, gaffe-prone public speaker.[86] The Democrats were confident: a popular slogan was that the Democrats "will pierce their enemies in 1852 as they poked [that is, Polked] them in 1844."[89] This proved true, as Scott won only Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts, and Vermont, finishing with 42 electoral votes to Pierce's 254. With 3.2 million votes cast, Pierce won the popular vote, 50.9% to 44.1%. A sizable block of Free Soilers broke for Pierce's in-state rival, Hale, who won 4.9% of the popular vote.[90][91] The Democrats took large majorities in Congress.[92]

Presidency (1853–1857)

[edit]Transition and train crash

[edit]

Pierce began his presidency in mourning. Weeks after his election, on January 6, 1853, he and his family were traveling from Boston by train when their car derailed and rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Both Franklin and Jane Pierce survived, but their only remaining son, 11-year-old Benjamin, was crushed to death in the wreckage, his body nearly decapitated. Pierce was not able to hide the sight from his wife. They both suffered severe depression afterward, which likely affected his performance as president.[93][94] Jane Pierce wondered whether the incident was divine punishment for her husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office. She wrote a lengthy letter of apology to "Benny" for her failings as a mother.[93] She avoided social functions for much of her first two years as First Lady, making her public debut in that role to great sympathy at the annual public reception held at the White House on New Year's Day 1855.[95]

When Franklin Pierce departed New Hampshire for the inauguration, Jane chose not to accompany him. Pierce, then the youngest man to be elected president, chose to affirm his oath of office on a law book rather than on a Bible, as all his predecessors except John Quincy Adams, who swore on a book of law,[96] had done. He was the first president to deliver his inaugural address from memory.[97] In it, he hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and urged a vigorous assertion of U.S. interests in its foreign relations, including the "eminently important" acquisition of new territories. "The policy of my Administration", he said, "will not be deterred by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion." Avoiding the word "slavery", he emphasized his desire to put the "important subject" to rest and maintain a peaceful union. He alluded to his own personal tragedy, telling the crowd, "You have summoned me in my weakness, you must sustain me by your strength."[98]

Administration and political strife

[edit]In his Cabinet appointments, Pierce sought to unite a party that was squabbling over the fruits of victory. Most in the party had not originally supported him for the nomination, and some had allied with the Free Soil party to gain victory in local elections. Pierce decided to allow each of the party's factions some appointments, even those that had not supported the Compromise of 1850.[99]

The Senate unanimously and immediately confirmed all of Pierce's Cabinet nominations.[100] Pierce spent the first few weeks of his term sorting through hundreds of lower-level federal positions to be filled. This was a chore, as he sought to represent all factions of the party, and could fully satisfy none of them. Partisans found themselves unable to secure positions for their friends, which put the Democratic Party on edge and fueled bitterness between factions. Before long, northern newspapers accused Pierce of filling his government with pro-slavery secessionists, while southern newspapers accused him of abolitionism.[100]

Factionalism between pro- and anti-administration Democrats ramped up quickly, especially within the New York Democratic Party. The more conservative Hardshell Democrats or "Hards" of New York were deeply skeptical of the Pierce administration, which was associated with Marcy (who became Secretary of State) and the more moderate New York faction, the Softshell Democrats or "Softs".[101]

Buchanan had urged Pierce to consult Vice President-elect King in selecting the Cabinet, but Pierce did not do so—Pierce and King had not communicated since they had been selected as candidates in June 1852. By the start of 1853, King was severely ill with tuberculosis, and went to Cuba to recuperate. His condition deteriorated, and Congress passed a special law allowing him to be sworn in before the American consul in Havana on March 24. Wanting to die at home, he returned to his plantation in Alabama on April 17 and died the next day. The office of vice president remained vacant for the remainder of Pierce's term, as the Constitution then had no provision for filling the vacancy. This extended vacancy meant that for nearly the entirety of Pierce's presidency the Senate President pro tempore, initially David Atchison of Missouri, was next in line to the presidency.[102]

Pierce sought to run a more efficient and accountable government than his predecessors.[103] His Cabinet members implemented an early system of civil service examinations, a forerunner to the Pendleton Act passed three decades later, which mandated that most U.S. government positions be awarded on the basis of merit, not patronage.[104] Secretary Robert McClelland reformed the Interior Department, systematizing its operations, expanding the use of paper records, and going after fraud.[105] Another of Pierce's reforms was to expand the role of the U.S. attorney general in appointing federal judges and attorneys, an important step in the eventual development of the Justice Department.[103] There was a vacancy on the Supreme Court—Fillmore, having failed to get Senate confirmation for his nominees, had offered it to newly elected Louisiana Senator Judah P. Benjamin, who had declined. Pierce also offered the seat to Benjamin, but he persisted in his refusal,[106] whereupon Pierce nominated John Archibald Campbell, an advocate of states' rights; this was Pierce's only Supreme Court appointment.[107]

Economic policy and internal improvements

[edit]

Pierce charged Treasury Secretary James Guthrie with reforming the Treasury, which was inefficiently managed and had many unsettled accounts. Guthrie increased oversight of Treasury employees and tariff collectors, many of whom were withholding money from the government. Despite laws requiring funds to be held in the Treasury, large deposits remained in private banks under the Whig administrations. Guthrie reclaimed these funds and sought to prosecute corrupt officials, with mixed success.[108]

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, at Pierce's request, led surveys by the Corps of Topographical Engineers of possible transcontinental railroad routes throughout the country. The Democratic Party had long rejected federal appropriations for internal improvements, but Davis felt that such a project could be justified as a Constitutional national security objective. Davis also deployed the Army Corps of Engineers to supervise construction projects in the District of Columbia, including the expansion of the United States Capitol and building of the Washington Monument.[109]

Foreign and military affairs

[edit]The Pierce administration aligned with the expansionist Young America movement, with Marcy leading the charge as secretary of state. Marcy sought to present to the world a distinctively American, republican image. He issued a circular recommending that U.S. diplomats wear "the simple dress of an American citizen" instead of the elaborate diplomatic uniforms worn in European courts, and that they hire only American citizens to work in consulates.[110][111] Marcy received international praise for his 73-page letter defending Austrian refugee Martin Koszta, who had been captured abroad in mid-1853 by the Austrian government despite his intention to become a U.S. citizen.[112][113]

An advocate of a southern transcontinental route, Davis persuaded Pierce to send rail magnate James Gadsden to Mexico to buy land for a potential railroad. Gadsden was also charged with renegotiating the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which required the U.S. to prevent Native American raids into Mexico from New Mexico Territory. Gadsden negotiated a treaty with Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna in December 1853, purchasing a large swath of land in the southwest. Negotiations were nearly derailed by William Walker's unauthorized expedition into Mexico, and so a clause was included charging the U.S. with combating future such attempts.[114][115] Congress reduced the Gadsden Purchase to the region now comprising southern Arizona and part of southern New Mexico; the price was cut from $15 million to $10 million. Congress also included a protection clause for a private citizen, Albert G. Sloo, whose interests were threatened by the purchase. Pierce opposed the use of the federal government to prop up private industry and did not endorse the final version of the treaty, but it was ratified nonetheless.[116][115] The acquisition brought the contiguous United States to its present-day boundaries, excepting later minor adjustments.[117]

| Pierce cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Franklin Pierce | 1853–1857 |

| Vice President | William R. King | 1853 |

| None | 1853–1857 | |

| Secretary of State | William L. Marcy | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | James Guthrie | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | 1853–1857 |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | 1853–1857 |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Navy | James C. Dobbin | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Robert McClelland | 1853–1857 |

Relations with Great Britain needed resolution, as American fishermen were upset at the British Royal Navy's increasing enforcement of Canadian territorial waters. Marcy completed a trade reciprocity agreement with the British minister to Washington, John Crampton, which reduced the need for British coastline enforcement. Buchanan was sent as minister to London to pressure the British government, which was slow to support a new treaty. A favorable reciprocity treaty was ratified in August 1854, which Pierce saw as a first step toward American annexation of Canada.[118][119] While the administration negotiated with Britain over the Canada–United States border, U.S. interests were also an issue in Central America, where the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 had failed to keep Britain from expanding its influence in the region. Gaining the advantage over Britain in the region was a key part of Pierce's expansionist goals.[120][121]

British consuls in the U.S. sought to enlist Americans for the Crimean War in 1854, in violation of neutrality laws, and Pierce eventually expelled Crampton and three consuls. To Pierce's surprise, the British did not expel Buchanan in retaliation. In his December 1855 State of the Union message to Congress, Pierce had set forth the American case that Britain had violated the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. According to Buchanan, the British were impressed by the message and were rethinking their policy. Nevertheless, Buchanan was unable to get them to abandon their Central American possessions. The Canadian-American Reciprocity Treaty was ratified by Congress, the British parliament, and Canada's colonial legislatures.[122]

Pierce's administration aroused sectional apprehensions when three U.S. diplomats in Europe drafted a proposal to the president to purchase Cuba from Spain for $120 million (USD), and justify the "wresting" of it from Spain if the offer were refused. The publication of the Ostend Manifesto, which had been drawn up at Secretary of State Marcy's insistence, provoked the scorn of northerners, who viewed it as an attempt to annex a slave-holding possession to bolster Southern interests. It helped discredit the expansionist policy of Manifest Destiny the Democratic Party had often supported.[123][124]

Pierce favored expansion and a substantial reorganization of the military. Secretary of War Davis and Navy Secretary James C. Dobbin found the Army and Navy in poor condition, with insufficient forces, a reluctance to adopt new technology, and inefficient management.[125] Under the Pierce administration, Commodore Matthew C. Perry visited Japan (a venture originally planned under Fillmore) in an effort to expand trade to the East. Perry wanted to encroach on Asia by force, but Pierce and Dobbin pushed him to remain diplomatic. Perry signed a modest trade treaty with the Japanese shogunate that was successfully ratified.[126][127] The 1856 launch of the USS Merrimac, one of six newly commissioned steam frigates, was one of Pierce's "most personally satisfying" days in office.[128]

Bleeding Kansas

[edit]

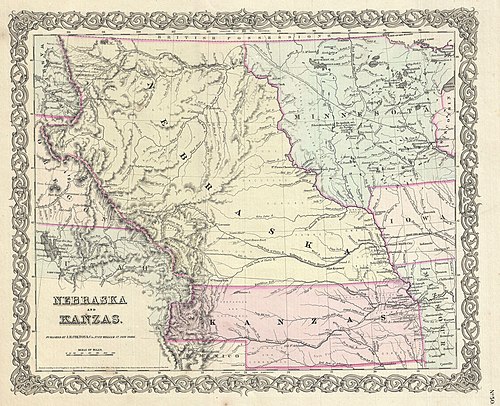

The greatest challenge to the country's equilibrium during the Pierce administration was the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Organizing the largely unsettled Nebraska Territory, which stretched from Missouri to the Rocky Mountains, and from Texas north to what is now the Canada–United States border, was a crucial part of Douglas's plans for western expansion. He wanted a transcontinental railroad with a link from Chicago to California, through the vast western territory. Organizing the territory was necessary for settlement as the land would not be surveyed nor put up for sale until a territorial government was authorized. Those from slave states had never been content with western limits on slavery, and felt it should be able to expand into territories procured with blood and treasure that had come, in part, from the South. Douglas and his allies planned to organize the territory and let local settlers decide whether to allow slavery. This would repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820, as most of it was north of the 36°30′ N line the Missouri Compromise deemed "free". The territory would be split into a northern part, Nebraska, and a southern part, Kansas, and the expectation was that Kansas would allow slavery and Nebraska would not.[129][130][131] In the view of pro-slavery Southern politicians, the Compromise of 1850 had already annulled the Missouri Compromise by admitting the state of California, including territory south of the compromise line, as a free state.[132]

Pierce had wanted to organize the Nebraska Territory without explicitly addressing the matter of slavery, but Douglas could not get enough Southern votes to accomplish this.[133] Pierce was skeptical of the bill, knowing it would result in bitter opposition from the North. Douglas and Davis convinced him to support the bill regardless. It was tenaciously opposed by northerners such as Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, who rallied public sentiment in the North against the bill. Northerners had been suspicious of the Gadsden Purchase, moves towards Cuba annexation, and the influence of slaveholding Cabinet members such as Davis, and saw the Nebraska bill as part of a pattern of southern aggression. The result was a political firestorm that did great damage to Pierce's presidency.[129][130][131]

Pierce and his administration used threats and promises to keep most Democrats on board in favor of the bill. The Whigs split along sectional lines; the conflict destroyed them as a national party. The Kansas–Nebraska Act was passed in May 1854 and ultimately defined the Pierce presidency. The political turmoil that followed the passage saw the short-term rise of the nativist and anti-Catholic American Party, often called the Know Nothings, and the founding of the Republican Party.[129][130][131]

Even as the act was being debated, settlers on both sides of the slavery issue poured into the territories so as to secure the outcome they wanted in the voting. The passage of the act resulted in so much violence between groups that the territory became known as Bleeding Kansas. Thousands of pro-slavery Border Ruffians came across from Missouri to vote in the territorial elections although they were not resident in Kansas, giving that element the victory. Pierce supported the outcome despite the irregularities. When Free-Staters set up a shadow government, and drafted the Topeka Constitution, Pierce called their work an act of rebellion. The president continued to recognize the pro-slavery legislature, which was dominated by Democrats, even after a Congressional investigative committee found its election to have been illegitimate. He dispatched federal troops to break up a meeting of the Topeka government.[136][137]

Passage of the act coincided with the seizure of escaped slave Anthony Burns in Boston. Northerners rallied in support of Burns, but Pierce was determined to follow the Fugitive Slave Act to the letter, and dispatched federal troops to enforce Burns's return to his Virginia owner despite furious crowds.[138][139]

The midterm congressional elections of 1854 and 1855 were devastating to the Democrats (as well as to the Whig Party, which was on its last legs). The Democrats lost almost every state outside the South. The administration's opponents in the North worked together to return opposition members to Congress, though only a few northern Whigs gained election. In Pierce's New Hampshire, hitherto loyal to the Democratic Party, the Know-Nothings elected the governor, all three representatives, dominated the legislature, and returned John P. Hale to the Senate. Anti-immigrant fervor brought the Know-Nothings their highest numbers to that point, and some northerners were elected under the auspices of the new Republican Party.[134][135]

1856 election

[edit]

Pierce fully expected to be renominated by the Democrats. In reality, his chances of winning the nomination (let alone the general election) were slim. The administration was widely disliked in the North for its position on the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and Democratic leaders were aware of Pierce's electoral vulnerability. Nevertheless, his supporters began to plan for an alliance with Douglas to deny James Buchanan the nomination. Buchanan had solid political connections and had been safely overseas through most of Pierce's term, leaving him untainted by the Kansas debacle.[141][142][143]

When balloting began on June 5 at the convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, Pierce expected a plurality, if not the required two-thirds majority. On the first ballot, he received only 122 votes, many of them from the South, to Buchanan's 135, with Douglas and Cass receiving the rest. By the following morning fourteen ballots had been completed, but none of the three main candidates were able to get two-thirds of the vote. Pierce, whose support had been slowly declining as the ballots passed, directed his supporters to break for Douglas, withdrawing his name in a last-ditch effort to defeat Buchanan. Douglas, only 43 years of age, believed that he could be nominated in 1860 if he let the older Buchanan win this time, and received assurances from Buchanan's managers that this would be the case. After two more deadlocked ballots, Douglas's managers withdrew his name, leaving Buchanan as the clear winner. To soften the blow to Pierce, the convention issued a resolution of "unqualified approbation" in praise of his administration and selected his ally, former Kentucky Representative John C. Breckinridge, as the vice-presidential nominee.[141][142][143] This loss marked the first time in U.S. history that an elected president who was an active candidate for reelection was not nominated by his political party for a second term.[note 6][144]

Pierce endorsed Buchanan, though the two remained distant; he hoped to resolve the Kansas situation by November to improve the Democrats' chances in the general election. He installed John W. Geary as territorial governor, who drew the ire of pro-slavery legislators.[145] Geary was able to restore order in Kansas, though the electoral damage had already been done—Republicans used "Bleeding Kansas" and "Bleeding Sumner" (the brutal caning of Charles Sumner by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks in the Senate chamber) as election slogans.[146] The Buchanan/Breckinridge ticket was elected, but the Democratic percentage of the popular vote in the North fell from 49.8 percent in 1852 to 41.4 in 1856 as Buchanan won only five of sixteen free states (Pierce had won fourteen), and in three of those, Buchanan won because of a split between the Republican candidate, former California senator John C. Frémont and the Know Nothing, former president Fillmore.[147]

Pierce did not temper his rhetoric after losing the nomination. In his final message to Congress, delivered in December 1856, he vigorously attacked Republicans and abolitionists. He took the opportunity to defend his record on fiscal policy, and on achieving peaceful relations with other nations.[148][149] In the final days of the Pierce administration, Congress passed bills to increase the pay of army officers and to build new naval vessels, also expanding the number of seamen enlisted. It also passed a tariff reduction bill he had long sought.[150] Pierce and his cabinet left office on March 4, 1857, the only time in U.S. history that the original cabinet members all remained for a full four-year term.[151]

Post-presidency (1857–1869)

[edit]

After leaving the White House, the Pierces remained in Washington for more than two months, staying with former Secretary of State William L. Marcy.[153] Buchanan altered course from the Pierce administration, replacing all his appointees. The Pierces eventually moved to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where Pierce had begun to speculate in property. Seeking warmer weather, he and Jane spent the next three years traveling, beginning with a stay in Madeira and followed by tours of Europe and the Bahamas.[152] In Rome, he visited Nathaniel Hawthorne; the two men spent much time together and the author found the retired president as buoyant as ever.[154]

Pierce never lost sight of politics during his travels, commenting regularly on the nation's growing sectional conflict. He insisted that northern abolitionists stand down to avoid a southern secession, writing that the bloodshed of a civil war would "not be along Mason and Dixon's line merely", but "within our own borders in our own streets".[152] He also criticized New England Protestant ministers, who largely supported abolition and Republican candidates, for their "heresy and treason".[152] The rise of the Republican Party forced the Democrats to defend Pierce; during his debates with Republican Senate candidate Abraham Lincoln in 1858, Douglas called the former president "a man of integrity and honor".[155]

As the Democratic Convention of 1860 approached, some asked Pierce to run as a compromise candidate that could unite the fractured party, but Pierce refused. As Douglas struggled to attract southern support, Pierce backed Cushing and then Breckinridge as potential alternatives, but his priority was a united Democratic Party. The split Democrats were soundly defeated for the presidency by the Republican candidate, Lincoln. In the months between Lincoln's election, and his inauguration on March 4, 1861, Pierce looked on as several southern states began plans to secede. He was asked by Justice Campbell to travel to Alabama and address that state's secession convention. Due to illness he declined, but sent a letter appealing to the people of Alabama to remain in the Union, and give the North time to repeal laws against southern interests and to find common ground.[156]

Civil War

[edit]After efforts to prevent the Civil War ended with the firing on Fort Sumter, Northern Democrats, including Douglas, endorsed Lincoln's plan to bring the Southern states back into the fold by force. Pierce wanted to avoid war at all costs, and wrote to Van Buren, proposing an assembly of former U.S. presidents to resolve the issue, but this suggestion was not acted on. "I will never justify, sustain or in any way or to any extent uphold this cruel, heartless, aimless, unnecessary war," Pierce wrote to his wife.[156] Pierce publicly opposed President Lincoln's order suspending the writ of habeas corpus, arguing that even in a time of war, the country should not abandon its protection of civil liberties. This stand won him admirers with the emerging Northern Peace Democrats, but others saw the stand as further evidence of Pierce's southern bias.[157]

In September 1861, Pierce traveled to Michigan, visiting his former Interior Secretary, McClelland, former senator Cass, and others. A Detroit bookseller, J. A. Roys, sent a letter to Lincoln's Secretary of State, William H. Seward, accusing the former president of meeting with disloyal people, and saying he had heard there was a plot to overthrow the government and establish Pierce as president. Later that month, the pro-administration Detroit Tribune printed an item calling Pierce "a prowling traitor spy", and intimating that he was a member of the pro-Confederate Knights of the Golden Circle. No such conspiracy existed, but a Pierce supporter, Guy S. Hopkins, sent to the Tribune a letter purporting to be from a member of the Knights of the Golden Circle, indicating that "President P." was part of a plot against the Union.[158][159] Hopkins intended for the Tribune to make the charges public, at which point Hopkins would admit authorship, thus making the Tribune editors seem overly partisan and gullible. Instead, the Tribune editors forwarded the Hopkins letter to government officials. Seward then ordered the arrest of possible "traitors" in Michigan, which included Hopkins. Hopkins confessed authorship of the letter and admitted the hoax, but despite this, Seward wrote to Pierce demanding to know if the charges were true. Pierce denied them, and Seward hastily backtracked. Later, Republican newspapers printed the Hopkins letter in spite of his admission that it was a hoax, and Pierce decided that he needed to clear his name publicly. When Seward refused to make their correspondence public, Pierce publicized his outrage by having a Senate ally, California's Milton Latham, read the letters between Seward and Pierce into the Congressional record, to the administration's embarrassment.[158][159]

The institution of the draft and the arrest of outspoken anti-administration Democrat Clement Vallandigham further incensed Pierce, who gave an address to New Hampshire Democrats in July 1863 vilifying Lincoln. "Who, I ask, has clothed the President with power to dictate to any one of us when we must or when we may speak, or be silent upon any subject, and especially in relation to the conduct of any public servant?", he demanded.[160][161] Pierce's comments were ill-received in much of the North, especially as his criticism of Lincoln's aims coincided with the twin Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Pierce's reputation in the North was further damaged the following month when the Mississippi plantation of the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, was seized by Union soldiers. Pierce's correspondence with Davis, all pre-war, revealing his deep friendship with Davis and predicting that civil war would result in insurrection in the North, was sent to the press. Pierce's words hardened abolitionist sentiment against him.[160][161]

Jane Pierce died of tuberculosis in Andover, Massachusetts in December 1863; she was buried at Old North Cemetery in Concord, New Hampshire. Pierce was further grieved by the death of his close friend Nathaniel Hawthorne in May 1864; he was with Hawthorne when the author died unexpectedly. Hawthorne had controversially dedicated his final book to Pierce. Some Democrats tried again to put Pierce's name up for consideration as the 1864 presidential election unfolded, but he kept his distance; Lincoln won a second term by a large margin. When news spread of Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, a mob gathered outside Pierce's home in Concord, demanding to know why he had not raised a flag as a public mourning gesture. Pierce grew angry, expressing sadness over Lincoln's death but denying any need for a public gesture. He told them that his history of military and public service proved his patriotism, which was enough to quiet the crowd.[162]

Final years and death

[edit]Pierce's drinking impaired his health in his last years, and he grew increasingly spiritual. He had a brief relationship with an unknown woman in mid-1865. During this time, he used his influence to improve the treatment of Davis, now a prisoner at Fort Monroe in Virginia. He also offered financial help to Hawthorne's son Julian, as well as to his own nephews. On the second anniversary of Jane's death, Pierce was baptized into his wife's Episcopal faith at St. Paul's Church in Concord. He found this church to be less political than his former Congregational denomination, which had alienated Democrats with anti-slavery rhetoric. He took up the life of an "old farmer", as he called himself, buying up property, drinking less, farming the land himself, and hosting visiting relatives.[163] He spent most of his time in Concord and his cottage at Little Boar's Head on the coast, sometimes visiting Jane's relatives in Massachusetts. Still interested in politics, he expressed support for Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction policy and supported the president's acquittal in his impeachment trial; he later expressed optimism for Johnson's successor, Ulysses S. Grant.[164]

Pierce's health began to decline again in mid-1869; he resumed heavy drinking despite his deteriorating physical condition. He returned to Concord that September, suffering from severe cirrhosis of the liver, knowing he would not recover. A caretaker was hired; none of his family members were present in his final days. He died at 4:35 am on Friday, October 8, 1869, at the age of 64. President Grant, who later defended Pierce's service in the Mexican-American War, declared a day of national mourning. Newspapers across the country carried lengthy front-page stories examining Pierce's colorful and controversial career. Pierce was interred next to his wife and two of his sons in the Minot enclosure at Concord's Old North Cemetery.[165]

In his last will, which he signed January 22, 1868, Pierce left a large number of specific bequests such as paintings, swords, horses, and other items to friends, family, and neighbors. Much of his $72,000 estate (equal to $1,700,000 today) went to his brother Henry's family, and to Hawthorne's children and Pierce's landlady. Henry's son Frank Pierce received the largest share.[166]

Sites, memorials, and honors

[edit]

In addition to his LL.D. from Norwich University, Pierce received honorary doctorates from Bowdoin College (1853) and Dartmouth College (1860).[167]

Two places in New Hampshire have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places specifically because of their association with Pierce. The Franklin Pierce Homestead in Hillsborough is a state park and a National Historic Landmark, open to the public.[5] The Franklin Pierce House in Concord, where Pierce died, was destroyed by fire in 1981, but is nevertheless listed on the register.[168] The Pierce Manse, his Concord home from 1842 to 1848, is open seasonally and maintained by a volunteer group, "The Pierce Brigade".[51] A statue of Pierce by Augustus Lukeman, dedicated in 1914,[169] stands on the grounds of the New Hampshire State House. Several New Hampshire historical markers commemorate Pierce and his family around New Hampshire.[170]

Several institutions and places have been named after Pierce, many in New Hampshire:

- The Franklin Pierce University in Rindge, New Hampshire, was chartered in 1962.[171]

- The University of New Hampshire School of Law was founded in 1973 as the Franklin Pierce Law Center. When the school was renamed in 2010, a Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property was established.[172]

- There is a Mt. Pierce in the Presidential Range of New Hampshire's White Mountains, renamed from Mt. Clinton in 1913.[173]

- The small town of Pierceton, Indiana, was founded in the 1850s and honors President Pierce.[174]

- Pierce County, Washington, the second most populous county in the state, is named in honor of President Pierce.[175]

- Pierce County, Georgia, established in 1857, is also named in honor of President Pierce.[176]

Legacy

[edit]After his death, Pierce mostly passed from the American consciousness, except as one of a series of presidents whose disastrous tenures led to civil war.[177] His presidency is widely regarded as a failure; he is often described as one of the worst presidents in American history.[note 7] The public placed him third-to-last among his peers in C-SPAN surveys (2000 and 2009).[182] Part of his failure was in allowing a divided Congress to take the initiative, most disastrously with the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Although he did not lead that fight—Senator Douglas did—Pierce paid the cost in damage to his reputation.[183] The failure of Pierce, as president, to secure sectional conciliation helped bring an end to the dominance of the Democratic Party that had started with Jackson, and led to a period of over seventy years when the Republicans mostly controlled national politics.[184]

Historian Eric Foner says, "His administration turned out to be one of the most disastrous in American history. It witnessed the collapse of the party system inherited from the Age of Jackson".[185]

Biographer Roy F. Nichols argues:[186][187]

As a national political leader Pierce was an accident. He was honest and tenacious of his views but, as he made up his mind with difficulty and often reversed himself before making a final decision, he gave a general impression of instability. Kind, courteous, generous, he attracted many individuals, but his attempts to satisfy all factions failed and made him many enemies. In carrying out his principles of strict construction he was most in accord with Southerners, who generally had the letter of the law on their side. He failed utterly to realize the depth and the sincerity of Northern feeling against the South and was bewildered at the general flouting of the law and the Constitution, as he described it, by the people of his own New England. At no time did he catch the popular imagination. His inability to cope with the difficult problems that arose early in his administration caused him to lose the respect of great numbers, especially in the North, and his few successes failed to restore public confidence. He was an inexperienced man, suddenly called to assume a tremendous responsibility, who honestly tried to do his best without adequate training or temperamental fitness.

Despite a reputation as an able politician and a likable man, during his presidency Pierce served only as a moderator among the increasingly bitter factions that were driving the nation towards civil war.[188] To Pierce, who saw slavery as a question of property rather than morality,[184] the Union was sacred; because of this, he saw the actions of abolitionists, and the more moderate Free Soilers, as divisive and as a threat to the constitutionally-guaranteed rights of southerners.[189] Although he criticized those who sought to limit or end slavery, he rarely rebuked southern politicians who took extreme positions or opposed northern interests.[190]

David Potter concludes that the Ostend Manifesto and the Kansas–Nebraska Act were "the two great calamities of the Franklin Pierce administration ... Both brought down an avalanche of public criticism."[191] More important, says Potter, they permanently discredited Manifest Destiny and "popular sovereignty" as political doctrines.[191] Historian Kenneth Nivison, writing in 2010, takes a more favorable view of Pierce's foreign policy, stating that his expansionism prefaced those of later presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, who served at a time when America had the military might to make her desires stick. "American foreign and commercial policy beginning in the 1890s, which eventually supplanted European colonialism by the middle of the twentieth century, owed much to the paternalism of Jacksonian Democracy cultivated in the international arena by the Presidency of Franklin Pierce."[192]

Historian and biographer Peter A. Wallner notes that:[193]

History has accorded to the Pierce administration a share of the blame for policies that incited the slavery issue, hastened the collapse of the second party system, and brought on the Civil War. ... It is both an inaccurate and unfair judgment. Pierce was always a nationalist attempting to find a middle ground to keep the Union together. ... The alternative to attempting to steer a moderate course was the breakup of the Union, the Civil War and the deaths of more than six hundred thousand Americans. Pierce should not be blamed for attempting throughout his political career to avoid this fate.

Historian Larry Gara, who authored a book on Pierce's presidency, wrote in the former president's entry in American National Biography Online:[194]

He was president at a time that called for almost superhuman skills, yet he lacked such skills and never grew into the job to which he had been elected. His view of the Constitution and the Union was from the Jacksonian past. He never fully understood the nature or depth of Free Soil sentiment in the North. He was able to negotiate a reciprocal trade treaty with Canada, to begin the opening of Japan to western trade, to add land to the Southwest, and to sign legislation for the creation of an overseas empire [the Guano Islands Act]. His Cuba and Kansas policies led only to deeper sectional strife. His support for the Kansas–Nebraska Act and his determination to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act helped polarize the sections. Pierce was hard-working and his administration largely untainted by graft, yet the legacy from those four turbulent years contributed to the tragedy of secession and civil war.

See also

[edit]- List of New Hampshire historical markers: Pierce Homestead, No. 65

- List of presidents of the United States

- List of presidents of the United States by previous experience

- New Hampshire historical marker no. 80: Franklin Pierce 1804–1869

- New Hampshire historical marker no. 125: The Pierce Manse

- New Hampshire historical marker no. 216: Pierce Shops

Notes

[edit]- ^ Vice President King died in office. As this was prior to the adoption of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967, the vacancy was not filled until the next election.

- ^ Some local accounts suggest he was born in the Homestead. The National Register of Historic Places cites the log cabin as the more likely birthplace,[6] and historian Peter A. Wallner asserts this is conclusively so.[7]

- ^ This was called the Republican or Jeffersonian Republican Party at the time; it soon became known as the Democratic-Republican Party. Modern writers prefer this term to distinguish it from the modern-day Republican Party.

- ^ The two-story school building burned some years later, and Hancock Academy was founded in 1836 to fill its place.[9]

- ^ The governor of New Hampshire was then elected annually; see also List of governors of New Hampshire.

- ^ Four other presidents—John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, and Chester Arthur—failed to be nominated for re-election by their respective parties; however, each of those four presidents had been elected vice president and had assumed the presidency after their respective predecessors had died in office.[144]

- ^ Wallner writes: "It is doubtful if any former president was as reviled in later life as Franklin Pierce was, and his reputation has hardly improved in the century and a half since his death. If anything, he has been forgotten and relegated to a footnote in history books—as an amiable nonentity who had no business being president and who reached that lofty position purely by the accident of circumstance."[178][179][180][181]

References

[edit]- ^ Coker, Jeffrey W. (2002). Presidents from Taylor Through Grant, 1849–1877: Debating the Issues in Pro and Con Primary Documents. Greenwood. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-3133-1551-0.

Attractive, polished, and outgoing, he was remembered by classmates more for his social skills than his scholarship... he married Jane Means Appleton, the daughter of Bowdoin College's president... Jane was a frail, somewhat sickly, and erratic woman who suffered from bouts of tuberculosis and deep depression... the two enjoyed a successful, if at time difficult, marriage.

- ^ "Presidential Historians Survey 2021". C-SPAN. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ https://www.usnews.com/news/special-reports/the-worst-presidents/articles/2014/12/17/worst-presidents-franklin-pierce-1853-1857

- ^ "Franklin Pierce, the tragic president".

- ^ a b "Pierce, Franklin, Homestead". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "Nomination Form: Franklin Pierce". National Register of Historic Places. 1976. p. 8. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Wallner 2004, p. 3

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 1–8

- ^ Hurd, D. Hamilton (1885). History of Hillsborough County, New Hampshire. Philadelphia: J.W. Lewis & Co. p. 350.

- ^ a b Wallner 2004, pp. 10–15

- ^ Gara 1991, pp. 35–36

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 16–21

- ^ Holt 2010, 229

- ^ Wallner, Peter A. (Spring 2005). "Franklin Pierce and Bowdoin College Associates Hawthorne and Hale" (PDF). Historical New Hampshire. New Hampshire Historical Society: 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 17, 2015.

Within the student body, Pierce's influence was widespread. Besides heading the Athenian Society, he also formed the only military company in the history of the college. "Captain" Pierce, in an attempt to provide recreation and instruction for his fellow students, led the Bowdoin Cadets in their daily drills on the grounds in front of the President's house. The Reverend William Allen, the college's president, objected to the noise and ordered a halt to the activity. When Pierce refused to comply with Allen's order, animosity grew between the students and the college authorities resulting in the junior class going on strike. Pierce was accused of leading the rebellion, but the college records do not acknowledge the event. Pierce's father took note of his son's role, however, and in a rare letter, admonished him about his behavior. In later years, classmates fondly recalled the strike and Pierce's key role.

- ^ Boulard 2006, p. 23

- ^ Waterman, Charles E. (March 7, 1918). "The Red Schoolhouse in Action". The Journal of Education. 87–88 (10). New England Publishing Company: 265. doi:10.1177/002205741808701007. S2CID 188507307.

- ^ Holt 2010, 230

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 28–32

- ^ Holt 2010, 258

- ^ Wallner 2004, p. 56

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 28–33

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 33–43

- ^ John Farmer, G. Parker Lyon, editors, The New-Hampshire Annual Register, and United States Calendar, 1832, p. 53.

- ^ Brian Matthew Jordan, Triumphant Mourner: The Tragic Dimension of Franklin Pierce, 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Betros, Lance (2004). West Point: Two Centuries and Beyond. McWhiney Foundation Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-893114-47-0. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Ellis, William Arba (1911). Norwich University, 1819–1911; Her History, Her Graduates, Her Roll of Honor, Volume 1. Capital City Press. pp. 87, 99. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Ellis, William Arba (1911). Norwich University, 1819–1911; Her History, Her Graduates, Her Roll of Honor, Volume 2. Capital City Press. pp. 14–16. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Wallner 2004, pp. 44–47

- ^ Holt 2010, locs. 273–300.

- ^ a b Wallner 2004, pp. 31–32, 77–78.

- ^ a b Gara 1991, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Baker, Jean H. "Franklin Pierce: Life Before the Presidency". American President: An Online Reference Resource. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

Franklin and Jane Pierce seemingly had little in common, and the marriage would sometimes be a troubled one. The bride's family were staunch Whigs, a party largely formed to oppose Andrew Jackson, whom Pierce revered. Socially, Jane Pierce was reserved and shy, the polar opposite of her new husband. Above all, she was a committed devotee of the temperance movement. She detested Washington and usually refused to live there, even after Franklin Pierce became a U.S. Senator in 1837.

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 79–80

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 241–244

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 47–57

- ^ a b Wallner 2004, pp. 57–59

- ^ Wallner 2004, p. 92

- ^ Wallner 2004, pp. 71–72

- ^ Wallner 2004, p. 67

- ^ Lamb, Brian; Wallner, Peter (October 25, 2004). "Interview with Peter Wallner: Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son". C-SPAN. 00:55:56.