Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Greedy coloring

View on Wikipedia

In the study of graph coloring problems in mathematics and computer science, a greedy coloring or sequential coloring[1] is a coloring of the vertices of a graph formed by a greedy algorithm that considers the vertices of the graph in sequence and assigns each vertex its first available color. Greedy colorings can be found in linear time, but they do not, in general, use the minimum number of colors possible.

Different choices of the sequence of vertices will typically produce different colorings of the given graph, so much of the study of greedy colorings has concerned how to find a good ordering. There always exists an ordering that produces an optimal coloring, but although such orderings can be found for many special classes of graphs, they are hard to find in general. Commonly used strategies for vertex ordering involve placing higher-degree vertices earlier than lower-degree vertices, or choosing vertices with fewer available colors in preference to vertices that are less constrained.

Variations of greedy coloring choose the colors in an online manner, without any knowledge of the structure of the uncolored part of the graph, or choose other colors than the first available in order to reduce the total number of colors. Greedy coloring algorithms have been applied to scheduling and register allocation problems, the analysis of combinatorial games, and the proofs of other mathematical results including Brooks' theorem on the relation between coloring and degree. Other concepts in graph theory derived from greedy colorings include the Grundy number of a graph (the largest number of colors that can be found by a greedy coloring), and the well-colored graphs, graphs for which all greedy colorings use the same number of colors.

Algorithm

[edit]The greedy coloring for a given vertex ordering can be computed by an algorithm that runs in linear time. The algorithm processes the vertices in the given ordering, assigning a color to each one as it is processed. The colors may be represented by the numbers and each vertex is given the color with the smallest number that is not already used by one of its neighbors. To find the smallest available color, one may use an array to count the number of neighbors of each color (or alternatively, to represent the set of colors of neighbors), and then scan the array to find the index of its first zero.[2]

In Python, the algorithm can be expressed as:

def first_available(colors):

"""Return smallest non-negative integer not in the given set of colors.

"""

color = 0

while color in colors:

color += 1

return color

def greedy_coloring(G, order):

"""Find the greedy coloring of G in the given order.

The representation of G is assumed to be like https://www.python.org/doc/essays/graphs/

in allowing neighbors of a node/vertex to be iterated over by "for w in G[node]".

The return value is a dictionary mapping vertices to their colors.

"""

coloring = dict()

for node in order:

used_neighbour_colors = {coloring[nbr]

for nbr in G[node]

if nbr in coloring}

coloring[node] = first_available(used_neighbour_colors)

return coloring

The first_available subroutine takes time proportional to the length of its argument list, because it performs two loops, one over the list itself and one over a list of counts that has the same length. The time for the overall coloring algorithm is dominated by the calls to this subroutine. Each edge in the graph contributes to only one of these calls, the one for the endpoint of the edge that is later in the vertex ordering. Therefore, the sum of the lengths of the argument lists to first_available, and the total time for the algorithm, are proportional to the number of edges in the graph.[2]

An alternative algorithm, producing the same coloring,[3] is to choose the sets of vertices with each color, one color at a time. In this method, each color class is chosen by scanning through the vertices in the given ordering. When this scan encounters an uncolored vertex that has no neighbor in , it adds to . In this way, becomes a maximal independent set among the vertices that were not already assigned smaller colors. The algorithm repeatedly finds color classes in this way until all vertices are colored. However, it involves making multiple scans of the graph, one scan for each color class, instead of the method outlined above which uses only a single scan.[4]

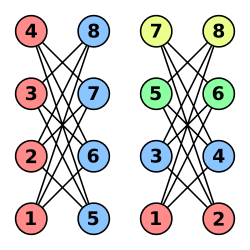

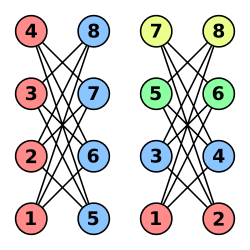

Choice of ordering

[edit]Different orderings of the vertices of a graph may cause the greedy coloring to use different numbers of colors, ranging from the optimal number of colors to, in some cases, a number of colors that is proportional to the number of vertices in the graph. For instance, a crown graph (a graph formed from two disjoint sets of n/2 vertices {a1, a2, ...} and {b1, b2, ...} by connecting ai to bj whenever i ≠ j) can be a particularly bad case for greedy coloring. With the vertex ordering a1, b1, a2, b2, ..., a greedy coloring will use n/2 colors, one color for each pair (ai, bi). However, the optimal number of colors for this graph is two, one color for the vertices ai and another for the vertices bi.[5] There also exist graphs such that with high probability a randomly chosen vertex ordering leads to a number of colors much larger than the minimum.[6] Therefore, it is of some importance in greedy coloring to choose the vertex ordering carefully.

Good orders

[edit]The vertices of any graph may always be ordered in such a way that the greedy algorithm produces an optimal coloring. For, given any optimal coloring, one may order the vertices by their colors. Then when one uses a greedy algorithm with this order, the resulting coloring is automatically optimal.[7] However, because optimal graph coloring is NP-complete, any subproblem that would allow this problem to be solved quickly, including finding an optimal ordering for greedy coloring, is NP-hard.[8]

In interval graphs and chordal graphs, if the vertices are ordered in the reverse of a perfect elimination ordering, then the earlier neighbors of every vertex will form a clique. This property causes the greedy coloring to produce an optimal coloring, because it never uses more colors than are required for each of these cliques. An elimination ordering can be found in linear time, when it exists.[9]

More strongly, any perfect elimination ordering is hereditarily optimal, meaning that it is optimal both for the graph itself and for all of its induced subgraphs. The perfectly orderable graphs (which include chordal graphs, comparability graphs, and distance-hereditary graphs) are defined as graphs that have a hereditarily optimal ordering.[10] Recognizing perfectly orderable graphs is also NP-complete.[11]

Bad orders

[edit]The number of colors produced by the greedy coloring for the worst ordering of a given graph is called its Grundy number.[12] Just as finding a good vertex ordering for greedy coloring is difficult, so is finding a bad vertex ordering. It is NP-complete to determine, for a given graph G and number k, whether there exists an ordering of the vertices of G that causes the greedy algorithm to use k or more colors. In particular, this means that it is difficult to find the worst ordering for G.[12]

Graphs for which order is irrelevant

[edit]The well-colored graphs are the graphs for which all vertex orderings produce the same number of colors. This number of colors, in these graphs, equals both the chromatic number and the Grundy number.[12] They include the cographs, which are exactly the graphs in which all induced subgraphs are well-colored.[13] However, it is co-NP-complete to determine whether a graph is well-colored.[12]

If a random graph is drawn from the Erdős–Rényi model with constant probability of including each edge, then any vertex ordering that is chosen independently of the graph edges leads to a coloring whose number of colors is close to twice the optimal value, with high probability. It remains unknown whether there is any polynomial time method for finding significantly better colorings of these graphs.[3]

Degeneracy

[edit]Because optimal vertex orderings are hard to find, heuristics have been used that attempt to reduce the number of colors while not guaranteeing an optimal number of colors. A commonly used ordering for greedy coloring is to choose a vertex v of minimum degree, order the subgraph with v removed recursively, and then place v last in the ordering. The largest degree of a removed vertex that this algorithm encounters is called the degeneracy of the graph, denoted d. In the context of greedy coloring, the same ordering strategy is also called the smallest last ordering.[14] This vertex ordering, and the degeneracy, may be computed in linear time.[15] It can be viewed as an improved version of an earlier vertex ordering method, the largest-first ordering, which sorts the vertices in descending order by their degrees.[16]

With the degeneracy ordering, the greedy coloring will use at most d + 1 colors. This is because, when colored, each vertex will have at most d already-colored neighbors, so one of the first d + 1 colors will be free for it to use.[17] Greedy coloring with the degeneracy ordering can find optimal colorings for certain classes of graphs, including trees, pseudoforests, and crown graphs.[18] Markossian, Gasparian & Reed (1996) define a graph to be -perfect if, for and every induced subgraph of , the chromatic number equals the degeneracy plus one. For these graphs, the greedy algorithm with the degeneracy ordering is always optimal.[19] Every -perfect graph must be an even-hole-free graph, because even cycles have chromatic number two and degeneracy two, not matching the equality in the definition of -perfect graphs. If a graph and its complement graph are both even-hole-free, they are both -perfect. The graphs that are both perfect graphs and -perfect graphs are exactly the chordal graphs. On even-hole-free graphs more generally, the degeneracy ordering approximates the optimal coloring to within at most twice the optimal number of colors; that is, its approximation ratio is 2.[20] On unit disk graphs its approximation ratio is 3.[21] The triangular prism is the smallest graph for which one of its degeneracy orderings leads to a non-optimal coloring, and the square antiprism is the smallest graph that cannot be optimally colored using any of its degeneracy orderings.[18]

Adaptive orders

[edit]Brélaz (1979) proposes a strategy, called DSatur, for vertex ordering in greedy coloring that interleaves the construction of the ordering with the coloring process. In his version of the greedy coloring algorithm, the next vertex to color at each step is chosen as the one with the largest number of distinct colors in its neighborhood. In case of ties, a vertex of maximal degree in the subgraph of uncolored vertices is chosen from the tied vertices. By keeping track of the sets of neighboring colors and their cardinalities at each step, it is possible to implement this method in linear time.[22]

This method can find the optimal colorings for bipartite graphs,[23] all cactus graphs, all wheel graphs, all graphs on at most six vertices, and almost every -colorable graph.[24] Although Lévêque & Maffray (2005) originally claimed that this method finds optimal colorings for the Meyniel graphs, they later found a counterexample to this claim.[25]

Alternative color selection schemes

[edit]It is possible to define variations of the greedy coloring algorithm in which the vertices of the given graph are colored in a given sequence but in which the color chosen for each vertex is not necessarily the first available color. These include methods in which the uncolored part of the graph is unknown to the algorithm, or in which the algorithm is given some freedom to make better coloring choices than the basic greedy algorithm would.

Online selection

[edit]Alternative color selection strategies have been studied within the framework of online algorithms. In the online graph-coloring problem, vertices of a graph are presented one at a time in an arbitrary order to a coloring algorithm; the algorithm must choose a color for each vertex, based only on the colors of and adjacencies among already-processed vertices. In this context, one measures the quality of a color selection strategy by its competitive ratio, the ratio between the number of colors it uses and the optimal number of colors for the given graph.[26]

If no additional restrictions on the graph are given, the optimal competitive ratio is only slightly sublinear.[27] However, for interval graphs, a constant competitive ratio is possible,[28] while for bipartite graphs and sparse graphs a logarithmic ratio can be achieved. Indeed, for sparse graphs, the standard greedy coloring strategy of choosing the first available color achieves this competitive ratio, and it is possible to prove a matching lower bound on the competitive ratio of any online coloring algorithm.[26]

Parsimonous coloring

[edit]A parsimonious coloring, for a given graph and vertex ordering, has been defined to be a coloring produced by a greedy algorithm that colors the vertices in the given order, and only introduces a new color when all previous colors are adjacent to the given vertex, but can choose which color to use (instead of always choosing the smallest) when it is able to re-use an existing color. The ordered chromatic number is the smallest number of colors that can be obtained for the given ordering in this way, and the ochromatic number is the largest ordered chromatic number among all vertex colorings of a given graph. Despite its different definition, the ochromatic number always equals the Grundy number.[29]

Applications

[edit]Because it is fast and in many cases can use few colors, greedy coloring can be used in applications where a good but not optimal graph coloring is needed. One of the early applications of the greedy algorithm was to problems such as course scheduling, in which a collection of tasks must be assigned to a given set of time slots, avoiding incompatible tasks being assigned to the same time slot.[4] It can also be used in compilers for register allocation, by applying it to a graph whose vertices represent values to be assigned to registers and whose edges represent conflicts between two values that cannot be assigned to the same register.[30] In many cases, these interference graphs are chordal graphs, allowing greedy coloring to produce an optimal register assignment.[31]

In combinatorial game theory, for an impartial game given in explicit form as a directed acyclic graph whose vertices represent game positions and whose edges represent valid moves from one position to another, the greedy coloring algorithm (using the reverse of a topological ordering of the graph) calculates the nim-value of each position. These values can be used to determine optimal play in any single game or any disjunctive sum of games.[32]

For a graph of maximum degree Δ, any greedy coloring will use at most Δ + 1 colors. Brooks' theorem states that with two exceptions (cliques and odd cycles) at most Δ colors are needed. One proof of Brooks' theorem involves finding a vertex ordering in which the first two vertices are adjacent to the final vertex but not adjacent to each other, and each vertex other than the last one has at least one later neighbor. For an ordering with this property, the greedy coloring algorithm uses at most Δ colors.[33]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mitchem (1976).

- ^ a b Hoàng & Sritharan (2016), Theorem 28.33, p. 738; Husfeldt (2015), Algorithm G

- ^ a b Frieze & McDiarmid (1997).

- ^ a b Welsh & Powell (1967).

- ^ Johnson (1974); Husfeldt (2015).

- ^ Kučera (1991); Husfeldt (2015).

- ^ Husfeldt (2015).

- ^ Maffray (2003).

- ^ Rose, Lueker & Tarjan (1976).

- ^ Chvátal (1984); Husfeldt (2015).

- ^ Middendorf & Pfeiffer (1990).

- ^ a b c d Zaker (2006).

- ^ Christen & Selkow (1979).

- ^ Mitchem (1976); Husfeldt (2015).

- ^ Matula & Beck (1983).

- ^ Welsh & Powell (1967); Husfeldt (2015).

- ^ Matula (1968); Szekeres & Wilf (1968).

- ^ a b Kosowski & Manuszewski (2004).

- ^ Markossian, Gasparian & Reed (1996); Maffray (2003).

- ^ Markossian, Gasparian & Reed (1996).

- ^ Gräf, Stumpf & Weißenfels (1998).

- ^ Brélaz (1979); Lévêque & Maffray (2005).

- ^ Brélaz (1979).

- ^ Janczewski et al. (2001).

- ^ Lévêque & Maffray (2005).

- ^ a b Irani (1994).

- ^ Lovász, Saks & Trotter (1989); Vishwanathan (1992).

- ^ Kierstead & Trotter (1981).

- ^ Simmons (1982); Erdős et al. (1987).

- ^ Poletto & Sarkar (1999). Although Poletto and Sarkar describe their register allocation method as not being based on graph coloring, it appears to be the same as greedy coloring.

- ^ Pereira & Palsberg (2005).

- ^ E.g., see Section 1.1 of Nivasch (2006).

- ^ Lovász (1975).

References

[edit]- Brélaz, Daniel (April 1979), "New methods to color the vertices of a graph", Communications of the ACM, 22 (4): 251–256, doi:10.1145/359094.359101, S2CID 14838769

- Christen, Claude A.; Selkow, Stanley M. (1979), "Some perfect coloring properties of graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 27 (1): 49–59, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(79)90067-4, MR 0539075

- Chvátal, Václav (1984), "Perfectly orderable graphs", in Berge, Claude; Chvátal, Václav (eds.), Topics in Perfect Graphs, Annals of Discrete Mathematics, vol. 21, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 63–68. As cited by Maffray (2003).

- Erdős, P.; Hare, W. R.; Hedetniemi, S. T.; Laskar, R. (1987), "On the equality of the Grundy and ochromatic numbers of a graph" (PDF), Journal of Graph Theory, 11 (2): 157–159, doi:10.1002/jgt.3190110205, MR 0889347.

- Frieze, Alan; McDiarmid, Colin (1997), "Algorithmic theory of random graphs", Random Structures & Algorithms, 10 (1–2): 5–42, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2418(199701/03)10:1/2<5::AID-RSA2>3.3.CO;2-6, MR 1611517.

- Gräf, A.; Stumpf, M.; Weißenfels, G. (1998), "On coloring unit disk graphs", Algorithmica, 20 (3): 277–293, doi:10.1007/PL00009196, MR 1489033, S2CID 36161020.

- Hoàng, Chinh T.; Sritharan, R. (2016), "Chapter 28. Perfect Graphs", in Thulasiraman, Krishnaiyan; Arumugam, Subramanian; Brandstädt, Andreas; Nishizeki, Takao (eds.), Handbook of Graph Theory, Combinatorial Optimization, and Algorithms, Chapman & Hall/CRC Computer and Information Science Series, vol. 34, CRC Press, pp. 707–750, ISBN 9781420011074.

- Husfeldt, Thore (2015), "Graph colouring algorithms", in Beineke, Lowell W.; Wilson, Robin J. (eds.), Topics in Chromatic Graph Theory, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 156, Cambridge University Press, pp. 277–303, arXiv:1505.05825, MR 3380176

- Irani, Sandy (1994), "Coloring inductive graphs on-line", Algorithmica, 11 (1): 53–72, doi:10.1007/BF01294263, MR 1247988, S2CID 181800.

- Janczewski, R.; Kubale, M.; Manuszewski, K.; Piwakowski, K. (2001), "The smallest hard-to-color graph for algorithm DSATUR", Discrete Mathematics, 236 (1–3): 151–165, doi:10.1016/S0012-365X(00)00439-8, MR 1830607.

- Kierstead, H. A.; Trotter, W. T. (1981), "An extremal problem in recursive combinatorics", Proceedings of the Twelfth Southeastern Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory and Computing, Vol. II (Baton Rouge, La., 1981), Congressus Numerantium, 33: 143–153, MR 0681909. As cited by Irani (1994).

- Kosowski, Adrian; Manuszewski, Krzysztof (2004), "Classical coloring of graphs", in Kubale, Marek (ed.), Graph Colorings, Contemporary Mathematics, vol. 352, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, pp. 1–19, doi:10.1090/conm/352/06369, ISBN 978-0-8218-3458-9, MR 2076987

- Kučera, Luděk (1991), "The greedy coloring is a bad probabilistic algorithm", Journal of Algorithms, 12 (4): 674–684, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(91)90040-6, MR 1130323.

- Johnson, David S. (1974), "Worst case behavior of graph coloring algorithms", Proceedings of the Fifth Southeastern Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory and Computing (Florida Atlantic Univ., Boca Raton, Fla., 1974), Congressus Numerantium, vol. X, Winnipeg, Manitoba: Utilitas Math., pp. 513–527, MR 0389644.

- Lévêque, Benjamin; Maffray, Frédéric (October 2005), "Coloring Meyniel graphs in linear time" (PDF), in Raspaud, André; Delmas, Olivier (eds.), 7th International Colloquium on Graph Theory (ICGT '05), 12–16 September 2005, Hyeres, France, Electronic Notes in Discrete Mathematics, vol. 22, Elsevier, pp. 25–28, arXiv:cs/0405059, doi:10.1016/j.endm.2005.06.005, S2CID 6262680. See also Lévêque, Benjamin; Maffray, Frédéric (January 9, 2006), Erratum : MCColor is not optimal on Meyniel graphs, arXiv:cs/0405059.

- Lovász, L. (1975), "Three short proofs in graph theory", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 19 (3): 269–271, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(75)90089-1, MR 0396344.

- Lovász, L.; Saks, M. E.; Trotter, W. T. (1989), "An on-line graph coloring algorithm with sublinear performance ratio", Discrete Mathematics, 75 (1–3): 319–325, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(89)90096-4, MR 1001404.

- Maffray, Frédéric (2003), "On the coloration of perfect graphs", in Reed, Bruce A.; Sales, Cláudia L. (eds.), Recent Advances in Algorithms and Combinatorics, CMS Books in Mathematics, vol. 11, Springer-Verlag, pp. 65–84, doi:10.1007/0-387-22444-0_3, ISBN 0-387-95434-1, MR 1952983.

- Markossian, S. E.; Gasparian, G. S.; Reed, B. A. (1996), "β-perfect graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B, 67 (1): 1–11, doi:10.1006/jctb.1996.0030, MR 1385380.

- Matula, David W. (1968), "A min-max theorem for graphs with application to graph coloring", SIAM 1968 National Meeting, SIAM Review, 10 (4): 481–482, doi:10.1137/1010115.

- Matula, David W.; Beck, L. L. (1983), "Smallest-last ordering and clustering and graph coloring algorithms", Journal of the ACM, 30 (3): 417–427, doi:10.1145/2402.322385, MR 0709826.

- Middendorf, Matthias; Pfeiffer, Frank (1990), "On the complexity of recognizing perfectly orderable graphs", Discrete Mathematics, 80 (3): 327–333, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(90)90251-C, MR 1049253.

- Mitchem, John (1976), "On various algorithms for estimating the chromatic number of a graph", The Computer Journal, 19 (2): 182–183, doi:10.1093/comjnl/19.2.182, MR 0437376.

- Nivasch, Gabriel (2006), "The Sprague–Grundy function of the game Euclid", Discrete Mathematics, 306 (21): 2798–2800, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2006.04.020, MR 2264378.

- Pereira, Fernando Magno Quintão; Palsberg, Jens (2005), "Register allocation via coloring of chordal graphs", in Yi, Kwangkeun (ed.), Programming Languages and Systems: Third Asian Symposium, APLAS 2005, Tsukuba, Japan, November 2–5, 2005, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 3780, Springer, pp. 315–329, doi:10.1007/11575467_21, ISBN 978-3-540-29735-2

- Poletto, Massimiliano; Sarkar, Vivek (September 1999), "Linear scan register allocation", ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 21 (5): 895–913, doi:10.1145/330249.330250, S2CID 18180752.

- Rose, D.; Lueker, George; Tarjan, Robert E. (1976), "Algorithmic aspects of vertex elimination on graphs", SIAM Journal on Computing, 5 (2): 266–283, doi:10.1137/0205021, MR 0408312.

- Simmons, Gustavus J. (1982), "The ordered chromatic number of planar maps", Proceedings of the thirteenth Southeastern conference on combinatorics, graph theory and computing (Boca Raton, Fla., 1982), Congressus Numerantium, 36: 59–67, MR 0726050

- Sysło, Maciej M. (1989), "Sequential coloring versus Welsh–Powell bound", Discrete Mathematics, 74 (1–2): 241–243, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(89)90212-4, MR 0989136.

- Szekeres, George; Wilf, Herbert S. (1968), "An inequality for the chromatic number of a graph", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, 4: 1–3, doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(68)80081-X.

- Vishwanathan, Sundar (1992), "Randomized online graph coloring", Journal of Algorithms, 13 (4): 657–669, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(92)90061-G, MR 1187207.

- Welsh, D. J. A.; Powell, M. B. (1967), "An upper bound for the chromatic number of a graph and its application to timetabling problems", The Computer Journal, 10 (1): 85–86, doi:10.1093/comjnl/10.1.85.

- Zaker, Manouchehr (2006), "Results on the Grundy chromatic number of graphs", Discrete Mathematics, 306 (2–3): 3166–3173, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2005.06.044, MR 2273147.

Greedy coloring

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

Greedy coloring is a heuristic algorithm for the graph coloring problem, which involves assigning colors to the vertices of an undirected graph such that no two adjacent vertices receive the same color. In this approach, vertices are considered in a predetermined order, and each vertex is assigned the smallest positive integer color that does not conflict with the colors already assigned to its neighboring vertices that appear earlier in the order.[4] A proper coloring of a graph is a vertex coloring where adjacent vertices have distinct colors. The chromatic number denotes the smallest number of colors needed to achieve a proper coloring of . The maximum degree is the largest number of edges incident to any single vertex in .[4] The greedy coloring algorithm guarantees a proper coloring of the graph, but the number of colors it uses may exceed , making it suboptimal in general. The algorithm operates in linear time with complexity , where is the number of vertices and is the number of edges.[4]Historical Development

The concept of greedy coloring originated in the mid-1960s as researchers sought practical heuristics for approximating the chromatic number of graphs, particularly in applications like timetabling. In 1967, D. J. A. Welsh and M. B. Powell introduced a seminal greedy algorithm that orders vertices in decreasing order of degree and assigns the smallest available color to each, establishing an upper bound of Δ(G) + 1 on the number of colors used, where Δ(G) is the maximum degree. This approach marked an early formalization of greedy strategies in graph coloring, building on broader combinatorial optimization techniques emerging in operations research.[5] Greedy coloring is inherently tied to the general paradigm of greedy algorithms, which prioritize local optimality in decision-making, and it gained traction as a heuristic for NP-hard coloring problems in the 1970s literature. Specific advancements in graph coloring heuristics were contributed by H. A. Kierstead and W. T. Trotter, who in 1988 explored online variants of greedy coloring, analyzing algorithms that color vertices as they appear and providing bounds on performance relative to the chromatic number. Their work highlighted the robustness of greedy methods in adversarial settings, influencing subsequent studies on competitive ratios for coloring.[6] The 1980s saw the development of key variants to improve greedy coloring's efficiency, notably the smallest-last ordering introduced by D. W. Matula and L. L. Beck in 1983. This strategy iteratively removes the vertex of smallest degree and colors in reverse order, yielding colorings bounded by the graph's degeneracy plus one, and it was applied to clustering and bandwidth minimization alongside coloring.[7] Such orderings refined the basic greedy framework, emphasizing the role of vertex sequencing in bounding resource usage.[8] Over time, greedy coloring integrated into broader greedy algorithm frameworks in graph theory, serving as a foundational example in algorithmic design for approximation and proof techniques without major post-2000 innovations altering its core historical trajectory.Core Algorithm

Step-by-Step Process

The greedy coloring algorithm proceeds by first selecting an arbitrary ordering of the vertices in the graph, denoted as , where is the number of vertices.[3] For each vertex in this sequence, the algorithm assigns the smallest positive integer color that is not used by any of its already-colored neighbors.[1] This neighbor checking involves examining only the adjacent vertices that appear earlier in the ordering , as subsequent vertices have not yet been colored.[9] To illustrate, consider a path graph with vertices and the ordering . The algorithm begins by assigning color 1 to , as it has no colored neighbors. For , which is adjacent to (colored 1), the smallest available color is 2. Next, for , adjacent to (colored 2), color 1 is available since has no other colored neighbors using it. Finally, for , adjacent to (colored 1), color 2 is assigned, as it avoids the color of . This results in the coloring: , , , .[3] The algorithm guarantees a proper coloring by construction, as each vertex receives a color distinct from all its previously colored neighbors, ensuring no adjacent vertices share the same color at the time of assignment; any adjacency to later vertices is handled when those vertices are colored.[1] The specific outcome, such as the number of colors used, can vary depending on the chosen ordering .[9]Pseudocode and Simple Example

The greedy coloring algorithm can be expressed in pseudocode as follows, where the input graph has vertices ordered as , and the output is a color assignment array using positive integers starting from 1.[10]function GreedyColor(G, order):

initialize color array c[1..n] = 0 // 0 indicates uncolored

for i = 1 to n:

v = order[i]

used = empty set

for each neighbor u of v:

if c[u] != 0:

add c[u] to used

c[v] = 1

while c[v] in used:

c[v] = c[v] + 1

return c

function GreedyColor(G, order):

initialize color array c[1..n] = 0 // 0 indicates uncolored

for i = 1 to n:

v = order[i]

used = empty set

for each neighbor u of v:

if c[u] != 0:

add c[u] to used

c[v] = 1

while c[v] in used:

c[v] = c[v] + 1

return c

used collects the colors of its already colored neighbors. The color is then set to the smallest positive integer not in used, found by starting at 1 and incrementing until an unused color is found.[10]

To illustrate, consider the cycle graph with vertices labeled and edges , , , , . The chromatic number , as it is an odd cycle requiring three colors for a proper coloring.[11] Applying the algorithm in the order :

- Color : no colored neighbors, so used = , assign 1.

- Color : neighbor colored 1, used = {1}, assign 2.

- Color : neighbor colored 2, used = {2}, assign 1.

- Color : neighbor colored 1, used = {1}, assign 2.

- Color : neighbors colored 2 and colored 1, used = {1,2}, assign 3.