Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Binary tree

View on Wikipedia

In computer science, a binary tree is a tree data structure in which each node has at most two children, referred to as the left child and the right child. That is, it is a k-ary tree where k = 2. A recursive definition using set theory is that a binary tree is a triple (L, S, R), where L and R are binary trees or the empty set and S is a singleton (a single–element set) containing the root.[1][2]

From a graph theory perspective, binary trees as defined here are arborescences.[3] A binary tree may thus be also called a bifurcating arborescence,[3] a term which appears in some early programming books[4] before the modern computer science terminology prevailed. It is also possible to interpret a binary tree as an undirected, rather than directed graph, in which case a binary tree is an ordered, rooted tree.[5] Some authors use rooted binary tree instead of binary tree to emphasize the fact that the tree is rooted, but as defined above, a binary tree is always rooted.[6]

In mathematics, what is termed binary tree can vary significantly from author to author. Some use the definition commonly used in computer science,[7] but others define it as every non-leaf having exactly two children and don't necessarily label the children as left and right either.[8]

In computing, binary trees can be used in two very different ways:

- First, as a means of accessing nodes based on some value or label associated with each node.[9] Binary trees labelled this way are used to implement binary search trees and binary heaps, and are used for efficient searching and sorting. The designation of non-root nodes as left or right child even when there is only one child present matters in some of these applications, in particular, it is significant in binary search trees.[10] However, the arrangement of particular nodes into the tree is not part of the conceptual information. For example, in a normal binary search tree the placement of nodes depends almost entirely on the order in which they were added, and can be re-arranged (for example by balancing) without changing the meaning.

- Second, as a representation of data with a relevant bifurcating structure. In such cases, the particular arrangement of nodes under and/or to the left or right of other nodes is part of the information (that is, changing it would change the meaning). Common examples occur with Huffman coding and cladograms. The everyday division of documents into chapters, sections, paragraphs, and so on is an analogous example with n-ary rather than binary trees.

Definitions

[edit]Recursive definition

[edit]Recursive full tree definition

[edit]A simple, informal approach to describe a binary tree might be as follows:

- a binary tree has a root node, which has 0 or 2 children nodes (which in turn may have their 0 or 2 children, and so on).

More formally:

- (base case) There exists a full tree consisting of a single node;

- (recursive step) If T1 and T2 are full binary trees, which do not share any node, and r is a node not belonging to T1 or T2, then the ordered triple (r, T1, T2) is a full binary tree.[11]

This definition implies two limitations: a full binary tree contains at least one node, and no node can have only one child. This is resolved with the next definition.

Recursive extended tree definition

[edit]The extended tree definition starts with the assumption the tree can be empty.

- (base case) An empty set of nodes is an extended binary tree.

- (recursive step) If T1 and T2 are extended binary trees, which do not share any node, and r is a node not belonging to any of them, then the ordered triple (r, T1, T2) is an extended binary tree.[12][11]

To be complete from the graph point of view, both definitions of a tree should be extended by a definition of the corresponding branches sets. Informally, the branches set can be described as a set of all ordered pairs of nodes (r, s) where r is a root node of any subtree appearing in the definition, and s is a root node of any of its T1 and T2 subtrees (in case the respective subtree is not empty).

Another way of imagining this construction (and understanding the terminology) is to consider instead of the empty set a different type of node—for instance square nodes if the regular ones are circles.[13]

Using graph theory concepts

[edit]A binary tree is a rooted tree that is also an ordered tree (a.k.a. plane tree) in which every node has at most two children. A rooted tree naturally imparts a notion of levels (distance from the root); thus, for every node, a notion of children may be defined as the nodes connected to it a level below. Ordering of these children (e.g., by drawing them on a plane) makes it possible to distinguish a left child from a right child.[14] But this still does not distinguish between a node with left but not a right child from a node with right but no left child.

The necessary distinction can be made by first partitioning the edges; i.e., defining the binary tree as triplet (V, E1, E2), where (V, E1 ∪ E2) is a rooted tree (equivalently arborescence) and E1 ∩ E2 is empty, and also requiring that for all j ∈ { 1, 2 }, every node has at most one Ej child.[15] A more informal way of making the distinction is to say, quoting the Encyclopedia of Mathematics, that "every node has a left child, a right child, neither, or both" and to specify that these "are all different" binary trees.[7]

Types of binary trees

[edit]Tree terminology is not well-standardized and therefore may vary among examples in the available literature.

- A full binary tree (sometimes referred to as a proper,[16] plane, or strict binary tree)[17][18] is a tree in which every node has either 0 or 2 children. Another way of defining a full binary tree is a recursive definition. A full binary tree is either:[12]

- A single vertex (a single node as the root node).

- A tree whose root node has two subtrees, both of which are full binary trees.

- A perfect binary tree is a binary tree in which all interior nodes have two children and all leaves have the same depth or same level (the level of a node defined as the number of edges or links from the root node to a node).[19] A perfect binary tree is a full binary tree.

- A complete binary tree is a binary tree in which every level, except possibly the last, is completely filled, and all nodes in the last level are as far left as possible. It can have between 1 and 2h nodes at the last level h.[20] A perfect tree is therefore always complete but a complete tree is not always perfect. Some authors use the term complete to refer instead to a perfect binary tree as defined above, in which case they call this type of tree (with a possibly not filled last level) an almost complete binary tree or nearly complete binary tree.[21][22] A complete binary tree can be efficiently represented using an array.[20]

- The infinite complete binary tree is a tree with levels, where for each level d the number of existing nodes at level d is equal to 2d. The cardinal number of the set of all levels is (countably infinite). The cardinal number of the set of all paths (the "leaves", so to speak) is uncountable, having the cardinality of the continuum.

- A balanced binary tree is a binary tree structure in which the left and right subtrees of every node differ in height (the number of edges from the top-most node to the farthest node in a subtree) by no more than 1 (or the skew is no greater than 1).[23] One may also consider binary trees where no leaf is much farther away from the root than any other leaf. (Different balancing schemes allow different definitions of "much farther".[24])

- A degenerate (or pathological) tree is where each parent node has only one associated child node.[25] This means that the tree will behave like a linked list data structure. In this case, an advantage of using a binary tree is significantly reduced because it is essentially a linked list which time complexity is O(n) (n as the number of nodes and 'O()' being the Big O notation) and it has more data space than the linked list due to two pointers per node, while the complexity of O(log2 n) for data search in a balanced binary tree is normally expected.

Properties of binary trees

[edit]- The number of nodes n in a full binary tree is at least and at most (i.e., the number of nodes in a perfect binary tree), where h is the height of the tree. A tree consisting of only a root node has a height of 0. The least number of nodes is obtained by adding only two children nodes per adding height so (1 for counting the root node). The maximum number of nodes is obtained by fully filling nodes at each level, i.e., it is a perfect tree. For a perfect tree, the number of nodes is , where the last equality is from the geometric series sum.

- The number of leaf nodes l in a perfect binary tree is (where n is the number of nodes in the tree) because (by using the above property) and the number of leaves is so . It also means that . In terms of the tree height h, .

- For any non-empty binary tree with leaf nodes and nodes of degree 2 (internal nodes with two child nodes), .[26] The proof is the following. For a perfect binary tree, the total number of nodes is (A perfect binary tree is a full binary tree.) and , so . To make a full binary tree from a perfect binary tree, a pair of two sibling nodes are removed one by one. This results in "two leaf nodes removed" and "one internal node removed" and "the removed internal node becoming a leaf node", so one leaf node and one internal node is removed per removing two sibling nodes. As a result, also holds for a full binary tree. To make a binary tree with a leaf node without its sibling, a single leaf node is removed from a full binary tree, then "one leaf node removed" and "one internal nodes with two children removed" so also holds. This relation now covers all non-empty binary trees.

- With given n nodes, the minimum possible tree height is with which the tree is a balanced full tree or perfect tree. With a given height h, the number of nodes can't exceed the as the number of nodes in a perfect tree. Thus .

- A binary Tree with l leaves has at least the height . With a given height h, the number of leaves at that height can't exceed as the number of leaves at the height in a perfect tree. Thus .

- In a non-empty binary tree, if n is the total number of nodes and e is the total number of edges, then . This is obvious because each node requires one edge except for the root node.

- The number of null links (i.e., absent children of the nodes) in a binary tree of n nodes is (n + 1).

- The number of internal nodes in a complete binary tree of n nodes is .

Combinatorics

[edit]In combinatorics, one considers the problem of counting the number of full binary trees of a given size. Here the trees have no values attached to their nodes (this would just multiply the number of possible trees by an easily determined factor), and trees are distinguished only by their structure; however, the left and right child of any node are distinguished (if they are different trees, then interchanging them will produce a tree distinct from the original one). The size of the tree is taken to be the number n of internal nodes (those with two children); the other nodes are leaf nodes and there are n + 1 of them. The number of such binary trees of size n is equal to the number of ways of fully parenthesizing a string of n + 1 symbols (representing leaves) separated by n binary operators (representing internal nodes), to determine the argument subexpressions of each operator. For instance for n = 3 one has to parenthesize a string like , which is possible in five ways:

The correspondence to binary trees should be obvious, and the addition of redundant parentheses (around an already parenthesized expression or around the full expression) is disallowed (or at least not counted as producing a new possibility).

There is a unique binary tree of size 0 (consisting of a single leaf), and any other binary tree is characterized by the pair of its left and right children; if these have sizes i and j respectively, the full tree has size i + j + 1. Therefore, the number of binary trees of size n has the following recursive description , and for any positive integer n. It follows that is the Catalan number of index n.

The above parenthesized strings should not be confused with the set of words of length 2n in the Dyck language, which consist only of parentheses in such a way that they are properly balanced. The number of such strings satisfies the same recursive description (each Dyck word of length 2n is determined by the Dyck subword enclosed by the initial '(' and its matching ')' together with the Dyck subword remaining after that closing parenthesis, whose lengths 2i and 2j satisfy i + j + 1 = n); this number is therefore also the Catalan number . So there are also five Dyck words of length 6:

- ()()(), ()(()), (())(), (()()), ((()))

These Dyck words do not correspond to binary trees in the same way. Instead, they are related by the following recursively defined bijection: the Dyck word equal to the empty string corresponds to the binary tree of size 0 with only one leaf. Any other Dyck word can be written as (), where , are themselves (possibly empty) Dyck words and where the two written parentheses are matched. The bijection is then defined by letting the words and correspond to the binary trees that are the left and right children of the root.

A bijective correspondence can also be defined as follows: enclose the Dyck word in an extra pair of parentheses, so that the result can be interpreted as a Lisp list expression (with the empty list () as only occurring atom); then the dotted-pair expression for that proper list is a fully parenthesized expression (with NIL as symbol and '.' as operator) describing the corresponding binary tree (which is, in fact, the internal representation of the proper list).

The ability to represent binary trees as strings of symbols and parentheses implies that binary trees can represent the elements of a free magma on a singleton set.

Methods for storing binary trees

[edit]Binary trees can be constructed from programming language primitives in several ways.

Nodes and references

[edit]In a language with records and references, binary trees are typically constructed by having a tree node structure which contains some data and references to its left child and its right child. Sometimes it also contains a reference to its unique parent. If a node has fewer than two children, some of the child pointers may be set to a special null value, or to a special sentinel node.

This method of storing binary trees wastes a fair bit of memory, as the pointers will be null (or point to the sentinel) more than half the time; a more conservative representation alternative is threaded binary tree.[27]

In languages with tagged unions such as ML, a tree node is often a tagged union of two types of nodes, one of which is a 3-tuple of data, left child, and right child, and the other of which is a "leaf" node, which contains no data and functions much like the null value in a language with pointers. For example, the following line of code in OCaml (an ML dialect) defines a binary tree that stores a character in each node.[28]

type chr_tree = Empty | Node of char * chr_tree * chr_tree

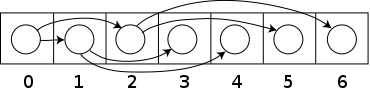

Arrays

[edit]Binary trees can also be stored in breadth-first order as an implicit data structure in arrays, and if the tree is a complete binary tree, this method wastes no space. In this compact arrangement, if a node has an index i, its children are found at indices (for the left child) and (for the right), while its parent (if any) is found at index (assuming the root has index zero). Alternatively, with a 1-indexed array, the implementation is simplified with children found at and , and parent found at .[29]

This method benefits from more compact storage and better locality of reference, particularly during a preorder traversal. It is often used for binary heaps.[30]

Encodings

[edit]Succinct encodings

[edit]A succinct data structure is one which occupies close to minimum possible space, as established by information theoretical lower bounds. The number of different binary trees on nodes is , the th Catalan number (assuming we view trees with identical structure as identical). For large , this is about ; thus we need at least about bits to encode it. A succinct binary tree therefore would occupy 2n+o(n) bits (with 'o()' being the Little-o notation).

One simple representation which meets this bound is to visit the nodes of the tree in preorder, outputting "1" for an internal node and "0" for a leaf.[31] If the tree contains data, we can simply simultaneously store it in a consecutive array in preorder. This function accomplishes this:

function EncodeSuccinct(node n, bitstring structure, array data) {

if n = nil then

append 0 to structure;

else

append 1 to structure;

append n.data to data;

EncodeSuccinct(n.left, structure, data);

EncodeSuccinct(n.right, structure, data);

}

The string structure has only bits in the end, where is the number of (internal) nodes; we don't even have to store its length. To show that no information is lost, we can convert the output back to the original tree like this:

function DecodeSuccinct(bitstring structure, array data) {

remove first bit of structure and put it in b

if b = 1 then

create a new node n

remove first element of data and put it in n.data

n.left = DecodeSuccinct(structure, data)

n.right = DecodeSuccinct(structure, data)

return n

else

return nil

}

More sophisticated succinct representations allow not only compact storage of trees but even useful operations on those trees directly while they're still in their succinct form.

Encoding ordered trees as binary trees

[edit]There is a natural one-to-one correspondence between ordered trees and binary trees. It allows any ordered tree to be uniquely represented as a binary tree, and vice versa:

Let T be a node of an ordered tree, and let B denote T's image in the corresponding binary tree. Then B's left child represents T's first child, while the B's right child represents T's next sibling.

For example, the ordered tree on the left and the binary tree on the right correspond:

In the pictured binary tree, the black, left, edges represent first child, while the blue, right, edges represent next sibling.

This representation is called a left-child right-sibling binary tree.

Common operations

[edit]

There are a variety of different operations that can be performed on binary trees. Some are mutator operations, while others simply return useful information about the tree.

Insertion

[edit]Nodes can be inserted into binary trees in between two other nodes or added after a leaf node. In binary trees, a node that is inserted is specified as to whose child it will be.

Leaf nodes

[edit]To add a new node after leaf node A, A assigns the new node as one of its children and the new node assigns node A as its parent.

Internal nodes

[edit]

Insertion on internal nodes is slightly more complex than on leaf nodes. Say that the internal node is node A and that node B is the child of A. (If the insertion is to insert a right child, then B is the right child of A, and similarly with a left child insertion.) A assigns its child to the new node and the new node assigns its parent to A. Then the new node assigns its child to B and B assigns its parent as the new node.

Deletion

[edit]Deletion is the process whereby a node is removed from the tree. Only certain nodes in a binary tree can be removed unambiguously.[32]

Node with zero or one children

[edit]

Suppose that the node to delete is node A. If A has no children, deletion is accomplished by setting the child of A's parent to null. If A has one child, set the parent of A's child to A's parent and set the child of A's parent to A's child.

Node with two children

[edit]In a binary tree, a node with two children cannot be deleted unambiguously.[32] However, in certain binary trees (including binary search trees) these nodes can be deleted, though with a rearrangement of the tree structure.

Traversal

[edit]Pre-order, in-order, and post-order traversal visit each node in a tree by recursively visiting each node in the left and right subtrees of the root. Below are the brief descriptions of above mentioned traversals.

Pre-order

[edit]In pre-order, we always visit the current node; next, we recursively traverse the current node's left subtree, and then we recursively traverse the current node's right subtree. The pre-order traversal is a topologically sorted one, because a parent node is processed before any of its child nodes is done.

In-order

[edit]In in-order, we always recursively traverse the current node's left subtree; next, we visit the current node, and lastly, we recursively traverse the current node's right subtree.

Post-order

[edit]In post-order, we always recursively traverse the current node's left subtree; next, we recursively traverse the current node's right subtree and then visit the current node. Post-order traversal can be useful to get postfix expression of a binary expression tree.[33]

Depth-first order

[edit]In depth-first order, we always attempt to visit the node farthest from the root node that we can, but with the caveat that it must be a child of a node we have already visited. Unlike a depth-first search on graphs, there is no need to remember all the nodes we have visited, because a tree cannot contain cycles. Pre-order is a special case of this. See depth-first search for more information.

Breadth-first order

[edit]Contrasting with depth-first order is breadth-first order, which always attempts to visit the node closest to the root that it has not already visited. See breadth-first search for more information. Also called a level-order traversal.

In a complete binary tree, a node's breadth-index (i − (2d − 1)) can be used as traversal instructions from the root. Reading bitwise from left to right, starting at bit d − 1, where d is the node's distance from the root (d = ⌊log2(i+1)⌋) and the node in question is not the root itself (d > 0). When the breadth-index is masked at bit d − 1, the bit values 0 and 1 mean to step either left or right, respectively. The process continues by successively checking the next bit to the right until there are no more. The rightmost bit indicates the final traversal from the desired node's parent to the node itself. There is a time-space trade-off between iterating a complete binary tree this way versus each node having pointer(s) to its sibling(s).

See also

[edit]- 2–3 tree

- 2–3–4 tree

- AA tree

- Ahnentafel

- AVL tree

- B-tree

- Binary space partitioning

- Huffman tree

- K-ary tree

- Kraft's inequality

- Merkle tree

- Optimal binary search tree

- Random binary tree

- Recursion (computer science)

- Red–black tree

- Rope (computer science)

- Self-balancing binary search tree

- Splay tree

- Strahler number

- Tree of primitive Pythagorean triples#Alternative methods of generating the tree

- Unrooted binary tree

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Rowan Garnier; John Taylor (2009). Discrete Mathematics:Proofs, Structures and Applications, Third Edition. CRC Press. p. 620. ISBN 978-1-4398-1280-8.

- ^ Steven S Skiena (2009). The Algorithm Design Manual. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-84800-070-4.

- ^ a b Knuth (1997). The Art Of Computer Programming, Volume 1, 3/E. Pearson Education. p. 363. ISBN 0-201-89683-4.

- ^ Iván Flores (1971). Computer programming system/360. Prentice-Hall. p. 39.

- ^ Kenneth Rosen (2011). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, 7th edition. McGraw-Hill Science. p. 749. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ David R. Mazur (2010). Combinatorics: A Guided Tour. Mathematical Association of America. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-88385-762-5.

- ^ a b "Binary tree", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994] also in print as Michiel Hazewinkel (1997). Encyclopaedia of Mathematics. Supplement I. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7923-4709-5.

- ^ L.R. Foulds (1992). Graph Theory Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-387-97599-3.

- ^ David Makinson (2009). Sets, Logic and Maths for Computing. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-84628-845-6.

- ^ Jonathan L. Gross (2007). Combinatorial Methods with Computer Applications. CRC Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-58488-743-0.

- ^ a b Long, Chengjiang (October 26, 2018), Lecture 22: Recursive Definitions and Structural Induction (PDF)

- ^ a b Kenneth Rosen (2011). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications 7th edition. McGraw-Hill Science. pp. 352–353. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ Te Chiang Hu; Man-tak Shing (2002). Combinatorial Algorithms. Courier Dover Publications. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-486-41962-6.

- ^ Lih-Hsing Hsu; Cheng-Kuan Lin (2008). Graph Theory and Interconnection Networks. CRC Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4200-4482-9.

- ^ J. Flum; M. Grohe (2006). Parameterized Complexity Theory. Springer. p. 245. ISBN 978-3-540-29953-0.

- ^ Tamassia, Michael T. Goodrich, Roberto (2011). Algorithm design : foundations, analysis, and Internet examples (2 ed.). New Delhi: Wiley-India. p. 76. ISBN 978-81-265-0986-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "full binary tree". NIST.

- ^ Richard Stanley, Enumerative Combinatorics, volume 2, p.36

- ^ "perfect binary tree". NIST.

- ^ a b "complete binary tree". NIST.

- ^ "almost complete binary tree". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ^ "nearly complete binary tree" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Aaron M. Tenenbaum, et al. Data Structures Using C, Prentice Hall, 1990 ISBN 0-13-199746-7

- ^ Paul E. Black (ed.), entry for data structure in Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 15 December 2004. Online version Accessed 2010-12-19.

- ^ Parmar, Anand K. (2020-01-22). "Different Types of Binary Tree with colourful illustrations". Medium. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ Mehta, Dinesh; Sartaj Sahni (2004). Handbook of Data Structures and Applications. Chapman and Hall. ISBN 1-58488-435-5.

- ^ D. Samanta (2004). Classic Data Structures. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 264–265. ISBN 978-81-203-1874-8.

- ^ Michael L. Scott (2009). Programming Language Pragmatics (3rd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-08-092299-7.

- ^ Introduction to algorithms. Cormen, Thomas H., Cormen, Thomas H. (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 2001. p. 128. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. OCLC 46792720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Laakso, Mikko. "Priority Queue and Binary Heap". University of Aalto. Retrieved 2023-10-11.

- ^ Demaine, Erik. "6.897: Advanced Data Structures Spring 2003 Lecture 12" (PDF). MIT CSAIL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 November 2005. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b Dung X. Nguyen (2003). "Binary Tree Structure". rice.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ Wittman, Todd (2015-02-13). "Lecture 18: Tree Traversals" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

Bibliography

[edit]- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming vol 1. Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4. Section 2.3, especially subsections 2.3.1–2.3.2 (pp. 318–348).

External links

[edit]- binary trees Archived 2020-09-23 at the Wayback Machine entry in the FindStat database

- Binary Tree Proof by Induction

- Balanced binary search tree on array How to create bottom-up an Ahnentafel list, or a balanced binary search tree on array

- Binary trees and Implementation of the same with working code examples

- Binary Tree and Graph Visualizer

- Binary Tree JavaScript Implementation with source code

- Top View of Binary tree

- Bottom View of Binary tree

- Left View of Binary tree

Binary tree

View on GrokipediaDefinitions

Recursive definition

A binary tree can be defined recursively as a data structure that is either empty or consists of a root node together with a left subtree and a right subtree, where each subtree is itself a binary tree.[8][1] This recursive structure captures the self-similar nature of binary trees, enabling them to grow to arbitrary depth by repeatedly applying the definition to the subtrees.[9] Formally, the set of binary trees satisfies the recursive equation: where denotes the empty tree, the root is a node, and the Cartesian products represent the left and right subtrees.[10][11] This definition permits nodes to have zero, one, or two children, depending on whether the subtrees are empty or non-empty. A variant known as a full binary tree imposes stricter recursive rules, where the base case is a single node (a leaf with zero children), and the recursive case requires a root with exactly two non-empty full binary subtrees, ensuring every internal node has precisely two children.[11][12] In contrast, an extended binary tree (or general binary tree allowing unary nodes) relaxes this by permitting subtrees to be empty in the recursive step, thus allowing nodes with one child.[11][13] For example, consider a binary tree with root node A, a left subtree consisting of node B (a leaf), and an empty right subtree; this unfolds recursively as the left subtree of A satisfying the base case for B, while the right satisfies the empty case, demonstrating a node with one child.[1]Graph-theoretic definition

In graph theory, a binary tree is a finite rooted directed acyclic graph in which the root node has indegree 0, every non-root node has indegree exactly 1, and every node has outdegree at most 2.[14] The directed edges point from parent nodes to their children, ensuring the structure is connected in the underlying undirected graph and free of directed cycles.[14] This formalization captures the hierarchical organization without allowing loops or multiple paths between nodes. In an ordered binary tree, the two possible outgoing edges from any node are distinguished as the left child and right child, imposing a linear order on siblings.[15] Unordered binary trees, by contrast, do not distinguish between left and right, treating the children as an unlabeled set.[15] The degree constraints ensure that leaves—nodes with outdegree 0—terminate branches, while internal nodes (non-leaves except possibly the root) have outdegree 1 or 2 and receive exactly one incoming edge, except for the root.[14] This graph-theoretic perspective provides a rigorous foundation for analyzing binary trees using tools from graph theory, such as connectivity and path properties, distinct from recursive constructions.[14] For illustration, consider a small ordered binary tree with four nodes: a root connected to left child (a leaf) and right child , where connects to its left child (a leaf). The directed edges are (left), (right), and (left), satisfying indegree and outdegree limits with no cycles. r

/ \

a b

/

c

r

/ \

a b

/

c

Properties

Structural properties

A binary tree consists of nodes connected by edges, where each node except the root has exactly one parent, ensuring a hierarchical structure without multiple incoming connections.[16] The subtrees rooted at the left and right children of any node are disjoint, meaning they share no nodes in common, which maintains the tree's partitioned organization.[17] The left and right subtrees of a node are structurally independent, allowing each to develop its own configuration without influencing the other, though they may exhibit mirroring symmetries in certain tree variants.[18] In any binary tree with nodes, the number of edges is exactly , as each non-root node contributes one incoming edge, forming a connected acyclic graph.[19] For a full binary tree, where every node has either zero or two children, the total number of nodes satisfies , with denoting the number of leaves; this relation arises because the number of leaves is one more than the number of internal nodes, as each internal node has two children and the tree has edges.[20] Binary trees contain no cycles, a property proven by the uniqueness of paths from the root: suppose a cycle exists; then any node on the cycle would have two distinct paths from the root (one direct and one via the cycle), contradicting the single-parent rule that ensures exactly one path to each node.[21]Height and size relationships

In binary trees, the height of a tree is defined as the number of edges on the longest path from the root node to a leaf node. The depth of a node is the number of edges on the path from the root to that node, with the root at depth 0.[5][22] For a binary tree with nodes, the minimum height is achieved when the tree is as balanced as possible, such as in a complete binary tree, where . This bound ensures the tree fills levels from left to right before advancing to deeper levels. In contrast, the maximum height occurs in a degenerate binary tree, resembling a linear chain, where .[23][24] Given a fixed height , a binary tree can hold a maximum of nodes, which is the case for a full binary tree where every level is completely filled and every node has either zero or two children. The minimum number of nodes for height is , occurring in a skewed configuration with a single path from root to leaf. Nodes in the tree are distributed across levels indexed from 0 (root) to , where the maximum number of nodes at level is .[25][26] These relationships between height and size directly influence the time complexity of tree operations. For instance, searching for a node requires traversing at most edges in the worst case, leading to time, which underscores the importance of minimizing height to improve efficiency in applications like search trees.[27][22]Types

Complete and perfect binary trees

A full binary tree, also known as a proper binary tree or 2-tree, is defined as a binary tree in which every node has either zero or two children, with no nodes having exactly one child.[22] This structure ensures that all internal nodes branch fully, leading to a strict alternation between internal nodes and leaves.[22] A complete binary tree is a binary tree in which every level, except possibly the last, is completely filled, and all nodes in the last level are as far to the left as possible.[22] This filling pattern from left to right makes complete binary trees particularly suitable for implementing priority queues like heaps, where the shape facilitates efficient operations.[28] Complete binary trees can have nodes with one child only in the last level, distinguishing them from full binary trees. A perfect binary tree is a special case where all levels are completely filled, with every internal node having exactly two children and all leaves at the same depth.[29] For a perfect binary tree of height (where the root is at height 0), the total number of nodes is given by the formula .[29] Every perfect binary tree is both full and complete, but the converse does not hold.[30] To illustrate the differences, consider simple textual representations: Full binary tree example (all nodes have 0 or 2 children, but levels may not be filled evenly): A

/ \

B C

/ \

D E

A

/ \

B C

/ \

D E

A

/ \

B C

/ \ /

D E F

A

/ \

B C

/ \ /

D E F

A

/ \

B C

/ \ / \

D E F G

A

/ \

B C

/ \ / \

D E F G

Balanced binary trees

A balanced binary tree is defined as a binary tree in which the heights of the left and right subtrees of every node differ by at most one.[33] This property ensures that the overall height of the tree remains logarithmic in the number of nodes, preventing degeneration into a linear structure.[34] Self-balancing binary trees automatically maintain this balance through rebalancing operations triggered by insertions and deletions, guaranteeing efficient performance.[35] AVL trees, named after their inventors Georgy Adelson-Velsky and Evgenii Landis, were the first self-balancing binary search trees, introduced in their 1962 paper on information organization algorithms.[36] They enforce a strict balance factor of at most one for every node by performing single or double rotations after structural modifications to restore height equilibrium.[37] This rigorous maintenance results in a tree height bounded by approximately 1.44 log₂(n + 2) - 0.328 for n nodes,[38] providing worst-case O(log n) time for key operations.[39] Red-black trees offer a more relaxed balancing approach, originally described by Rudolf Bayer in 1972 as symmetric binary B-trees, later formalized with color attributes. Each node is colored red or black, with properties ensuring no two red nodes are adjacent and that all paths from a node to its descendant leaves contain the same number of black nodes.[40] These rules limit the height to at most twice the height of a perfectly balanced tree, yielding O(log n) operations while allowing fewer rotations than AVL trees during rebalancing.[41] Splay trees, invented by Daniel Sleator and Robert Tarjan in 1985, achieve balance through amortized analysis rather than strict height constraints.[42] Upon accessing a node, it is "splayed" to the root via a series of rotations, promoting frequently accessed elements and ensuring that any sequence of m operations takes O(m log n + n log n) time in the worst case.[43] This self-adjusting mechanism adapts to access patterns without explicit balance factors, often outperforming other balanced trees for non-uniform distributions.[44] The primary benefit of balanced binary trees like AVL, red-black, and splay trees is their assurance of O(log n) worst-case or amortized time complexity for insertions, deletions, and searches, in contrast to the potential O(n) degradation in unbalanced binary search trees.[45] This efficiency is crucial for applications requiring dynamic data management, such as databases and file systems, where maintaining logarithmic access times scales with large datasets.[35]Combinatorics

Enumeration of binary trees

The enumeration of binary trees typically focuses on unlabeled plane binary trees, which are rooted structures where the order of subtrees matters, distinguishing between left and right children, and nodes are indistinguishable except by their positions in the hierarchy.[46] The number of such distinct binary trees with exactly nodes is given by the th Catalan number .[46] This count arises from considering the root node and partitioning the remaining nodes between the left and right subtrees. Based on the recursive definition of binary trees, the enumeration satisfies the recurrence relation for , with base cases (empty tree) and (single root node).[46] For example, with nodes, there are possible shapes: one where the root has two leaf children; two where the root has only a left child that itself has one leaf child (either left or right); and two symmetric cases where the root has only a right child that itself has one leaf child (either left or right).[46] These enumerative results have applications in combinatorics and computer science, particularly in counting the possible parse trees for expressions in context-free grammars, where binary trees model operator precedence and associativity.[46] They also inform the design and analysis of sorting networks, where the structural variety of binary trees helps enumerate decision paths in parallel comparison-based sorting architectures.[47]Catalan numbers in binary trees

The nth Catalan number is defined as where denotes the central binomial coefficient.[48] This sequence arises in numerous combinatorial contexts, with , , , , and so on.[49] In the context of binary trees, the nth Catalan number enumerates the number of distinct rooted plane binary trees with leaves, where each internal node has exactly two children.[49] Equivalently, counts the number of such binary trees with internal nodes. This interpretation highlights the recursive structure of binary trees: a tree with internal nodes consists of a root connected to a left subtree with internal nodes and a right subtree with internal nodes, for to , leading to the recurrence with .[48] The ordinary generating function for the Catalan numbers is which satisfies the functional equation derived from the recursive decomposition of binary trees.[48] This equation mirrors the way a binary tree is formed by attaching two subtrees to the root, providing a generating function approach to count the trees. A standard proof of the Catalan number formula in this setting relies on a bijection between rooted plane binary trees with leaves and valid sequences of pairs of balanced parentheses.[50] The mapping proceeds recursively: the empty tree corresponds to the empty sequence; otherwise, the sequence for a tree is the left subtree's sequence enclosed in parentheses, followed by the right subtree's sequence. This bijection preserves the recursive structure and directly yields the count , as the number of valid parenthesis sequences is also given by the Catalan formula. An analogous bijection exists with Dyck paths of semilength , which can be interpreted as the "heights" traversed in a tree's structure, further confirming the enumeration.[48] An important extension is that also counts the number of full binary trees (where every node has either zero or two children) with exactly nodes, since such trees have internal nodes and leaves. This provides a foundational tool for enumerating binary trees, as discussed in the broader enumeration section. The Catalan numbers are named after the Belgian mathematician Eugène Charles Catalan, who first studied them in 1838 while investigating combinatorial problems related to successive roots and combinations.[51] Although the explicit connection to binary trees emerged later, combinatorial interpretations including tree structures were recognized in 19th-century works building on these foundations.[52]Representations

Node-based storage

In node-based storage, binary trees are implemented as a collection of dynamically allocated nodes linked via pointers, allowing for flexible representation of arbitrary tree structures. Each node typically stores the associated data value along with two pointers: one to the left child and one to the right child, enabling the hierarchical organization of the tree. This structure supports null pointers for leaves or missing children, ensuring that every node has at most two children. Optionally, an additional parent pointer can be included in each node to simplify navigation and operations such as deletion in bidirectional traversal scenarios.[22][53] Memory management in this representation relies on dynamic allocation for each node, which incurs overhead beyond the data itself—typically the space for two (or three) pointers, each requiring 4 or 8 bytes depending on the system architecture. This pointer overhead can represent a significant portion of memory usage, especially for trees with small data elements, but it avoids wasting space on non-existent nodes unlike contiguous representations. Dynamic allocation, often handled by language runtimes or manual calls in languages like C, allows the tree to grow or shrink as needed without predefined size limits. However, frequent allocations and deallocations can lead to external memory fragmentation, where free memory becomes scattered in small blocks unsuitable for larger requests.[54] The primary advantages of node-based storage lie in its adaptability to unbalanced or irregular tree shapes, making it ideal for scenarios where the tree structure evolves unpredictably. Insertion and deletion operations are efficient and intuitive, involving only pointer adjustments rather than shifting elements, which supports O(1) local changes after locating the position. This flexibility is particularly valuable in general-purpose applications, such as implementing binary search trees for dynamic sets or expression trees in compilers.[55][56] Despite these benefits, node-based storage has notable drawbacks, including reduced cache efficiency due to pointer chasing, where traversing the tree requires jumping between non-contiguous memory locations, leading to frequent cache misses and slower access times compared to contiguous alternatives. The additional pointer storage also increases overall memory footprint, and in unbalanced trees, performance can degrade to linear time in the worst case, mimicking a linked list. To illustrate the node definition, the following pseudocode shows a basic class in a language-agnostic style, commonly used in implementations with languages supporting object-oriented or structured programming:class Node {

[data](/page/Data) // The value stored in the node

left: Node | null // Pointer to left [child](/page/Child)

right: Node | null // Pointer to right [child](/page/Child)

// Optional: [parent](/page/Parent): Node | null // Pointer to [parent](/page/Parent) node

constructor(value) {

this.[data](/page/Data) = value

this.left = null

this.right = null

// this.[parent](/page/Parent) = null

}

}

class Node {

[data](/page/Data) // The value stored in the node

left: Node | null // Pointer to left [child](/page/Child)

right: Node | null // Pointer to right [child](/page/Child)

// Optional: [parent](/page/Parent): Node | null // Pointer to [parent](/page/Parent) node

constructor(value) {

this.[data](/page/Data) = value

this.left = null

this.right = null

// this.[parent](/page/Parent) = null

}

}

Array-based storage

Array-based storage represents a binary tree using a single contiguous array, eliminating the need for explicit pointers between nodes and making it particularly suitable for complete binary trees where nodes are filled level by level from left to right.[57] A common convention places the root node at index 1 (with index 0 often left unused as a sentinel), the left child of a node at index at , and the right child at ; alternatively, 0-based indexing places the root at index 0, left child at , and right child at . This indexing allows direct computation of parent-child relationships using simple arithmetic: for 1-based, the parent of a node at index (for ) is at ; for 0-based, it is at .[58] The space complexity is for a tree with nodes, as each node occupies one array slot without additional overhead for pointers, assuming the array is sized appropriately for the complete structure.[57] This contiguous layout enhances cache efficiency, enabling faster access patterns in memory compared to pointer-based methods, and supports constant-time computation for locating children or parents.[59] However, this representation assumes the tree is complete or nearly complete; sparse trees waste space in unused array positions, and fixed-size arrays limit dynamic growth without resizing, which can introduce overhead.[57] For insertion in a complete binary tree, a new node is added at the next available position in level order (the end of the current array), maintaining the complete property, after which adjustments like heapifying up may be applied if the tree enforces additional ordering (e.g., in binary heaps). Consider a small complete binary tree with root value 1, left child 2, right child 3, and 2 having a left child 4. This is represented in the array as[-, 1, 2, 3, 4], where the leading - denotes the unused index 0, and positions 1 through 4 hold the node values in level order.

Encodings

Succinct encodings

Succinct encodings for binary trees aim to represent the structure of an n-node ordered binary tree using 2n + o(n bits of space, approaching the information-theoretic lower bound of approximately 2n bits needed to distinguish among the Catalan number C_n of possible structures, in contrast to the Θ(n log n) bits required by conventional node-based storage that allocates words for left and right child pointers per node.[60] One foundational approach is the balanced parenthesis (BP) representation, which captures the tree's topology via a depth-first traversal. During traversal, an opening parenthesis '(' is recorded upon descending to a child subtree, and a closing parenthesis ')' upon ascending from a node; leaves contribute a single pair '()'. This yields exactly 2n bits for n nodes, as each node corresponds to one opening and one closing parenthesis. For instance, a root with a left leaf child and a right child that itself has left and right leaf children encodes as "(()(()()))", where the inner "()" (after the initial open) denotes the left leaf, and "(()())" the right subtree.[60] To enable efficient querying on this bit sequence, succinct encodings incorporate rank and select data structures. The rank operation computes the number of opening parentheses up to a given position, while select identifies the position of the k-th opening parenthesis. Preprocessing the BP sequence with o(n) extra bits—typically O(n log log n / log n)—allows both operations in O(1) time, supporting key tree navigations such as finding a node's parent, left or right child, depth, or subtree size in constant time.[60] These encodings find application in succinct data structure libraries, such as the Succinct Data Structure Library (SDSL), where they enable compact storage and fast access for large-scale tree-based indexes in bioinformatics and information retrieval.Encoding general trees as binary trees

One common technique for encoding general ordered trees, including m-ary trees where m can vary, as binary trees is the first-child/next-sibling representation, also known as the left-child/right-sibling or Knuth transform.[29] In this method, each node in the binary tree structure uses its left pointer to reference the first child of the corresponding node in the original general tree, and its right pointer to reference the next sibling in the ordered list of children.[4] This approach requires only two pointers per node, providing O(1) additional space overhead beyond the original tree's node storage, regardless of the degree m, by chaining siblings into a linked list via right pointers.[61] The method was proposed by Donald Knuth in the 1960s to enable uniform algorithmic treatment of multi-way trees using binary tree operations, as detailed in his seminal work on fundamental algorithms. It preserves the ordered structure of children in the general tree, maintaining ancestry relationships through the left-child chains, which form the subtrees, while the right-sibling links ensure traversal follows the original sibling order. This encoding is reversible, allowing reconstruction of the original general tree from the binary representation without loss of information. A key advantage is the ability to apply standard binary tree traversal and manipulation algorithms—such as in-order or level-order traversals—to general trees, facilitating implementation in systems optimized for binary structures and reducing code complexity for handling variable-arity nodes.[62] For instance, depth-first traversal in the encoded binary tree can mimic pre-order traversal of the original tree by following left subtrees (children) before right links (siblings). To illustrate, consider a simple ternary tree with root A having children B, C, and D, where B has child E, C has children F and G, and D is a leaf. In the binary encoding:- A's left points to B (first child), and B's right points to C (B's next sibling), C's right points to D (C's next sibling), D's right is null.

- B's left points to E (B's first child), E's right is null.

- C's left points to F (C's first child), F's right points to G (F's next sibling), G's right is null.

- D's left is null (no children).

Operations

Insertion and deletion

Insertion in a binary tree, particularly in the context of binary search trees (BSTs), involves adding a new node while preserving the tree's structure and properties. For a BST, the algorithm starts at the root and compares the new key with the current node's key, traversing left if smaller or right if larger, until reaching a null child pointer where the new node is attached as a leaf. This recursive placement ensures the BST property: all nodes in the left subtree have keys less than the parent, and all in the right subtree have keys greater. The operation takes O(h) time, where h is the tree's height, which is O(log n) on average for balanced trees but O(n) in the worst case for skewed ones.[63] For an empty tree, insertion creates the new node as the root. Pseudocode for BST insertion, adapted from standard recursive implementations, is as follows:function insert([root](/page/Root), key):

if [root](/page/Root) is null:

return new Node(key)

if key < [root](/page/Root).key:

[root](/page/Root).left = insert([root](/page/Root).left, key)

elif key > [root](/page/Root).key:

[root](/page/Root).right = insert([root](/page/Root).right, key)

return [root](/page/Root)

function insert([root](/page/Root), key):

if [root](/page/Root) is null:

return new Node(key)

if key < [root](/page/Root).key:

[root](/page/Root).left = insert([root](/page/Root).left, key)

elif key > [root](/page/Root).key:

[root](/page/Root).right = insert([root](/page/Root).right, key)

return [root](/page/Root)

function delete(root, key):

if root is null:

return root

if key < root.key:

root.left = delete(root.left, key)

elif key > root.key:

root.right = delete(root.right, key)

else:

# Node found

if root.left is null:

return root.right

elif root.right is null:

return root.left

else:

successor = findMin(root.right)

root.key = successor.key

root.right = delete(root.right, successor.key)

return root

function findMin(node):

while node.left is not null:

node = node.left

return node

function delete(root, key):

if root is null:

return root

if key < root.key:

root.left = delete(root.left, key)

elif key > root.key:

root.right = delete(root.right, key)

else:

# Node found

if root.left is null:

return root.right

elif root.right is null:

return root.left

else:

successor = findMin(root.right)

root.key = successor.key

root.right = delete(root.right, successor.key)

return root

function findMin(node):

while node.left is not null:

node = node.left

return node

Traversal methods

Binary tree traversal refers to the process of visiting each node in the tree exactly once in a systematic manner, enabling operations such as printing, searching, or processing node data. These methods are fundamental for analyzing and manipulating binary trees, with algorithms typically achieving O(n time complexity, where n is the number of nodes, since each node is processed once. Space complexity varies by approach, often O(h) for recursive methods, where h is the tree height, due to the call stack or explicit data structures like stacks or queues.[65][66]Depth-First Traversals

Depth-first traversals (DFS) explore as far as possible along each branch before backtracking, encompassing three primary variants: preorder, inorder, and postorder. These can be implemented recursively or iteratively using a stack, with recursive versions being simpler but consuming O(h) space in the worst case for skewed trees. Iterative versions mimic recursion explicitly with a stack, also requiring O(h) space.[67][68] Preorder traversal visits the root node first, followed by the left subtree, then the right subtree. This order is useful for creating a copy of the tree or serializing it to prefix notation. The recursive pseudocode is as follows:function preorder([root](/page/Root)):

if [root](/page/Root) is null:

return

visit [root](/page/Root)

preorder([root](/page/Root).left)

preorder([root](/page/Root).right)

function preorder([root](/page/Root)):

if [root](/page/Root) is null:

return

visit [root](/page/Root)

preorder([root](/page/Root).left)

preorder([root](/page/Root).right)

function inorder(root):

if root is null:

return

inorder(root.left)

visit root

inorder(root.right)

function inorder(root):

if root is null:

return

inorder(root.left)

visit root

inorder(root.right)

function postorder(root):

if root is null:

return

postorder(root.left)

postorder(root.right)

visit root

function postorder(root):

if root is null:

return

postorder(root.left)

postorder(root.right)

visit root

Breadth-First Traversal

Breadth-first traversal, also known as level-order traversal, visits nodes level by level, starting from the root and proceeding left to right across each level. This uses a queue to enqueue the root, then repeatedly dequeues a node, visits it, and enqueues its children. The pseudocode is:function levelOrder([root](/page/Root)):

if [root](/page/Root) is null:

return

queue = new Queue()

queue.enqueue([root](/page/Root))

while queue is not empty:

current = queue.dequeue()

visit current

if current.left is not null:

queue.enqueue(current.left)

if current.right is not null:

queue.enqueue(current.right)

function levelOrder([root](/page/Root)):

if [root](/page/Root) is null:

return

queue = new Queue()

queue.enqueue([root](/page/Root))

while queue is not empty:

current = queue.dequeue()

visit current

if current.left is not null:

queue.enqueue(current.left)

if current.right is not null:

queue.enqueue(current.right)

Morris Traversal

Morris traversal provides an in-order traversal using O(1) extra space by temporarily modifying the tree's structure through "threading"—linking nodes to their in-order successors via unused right-child pointers—then restoring the links during traversal. Introduced by J. H. Morris, it achieves O(n) time by visiting each node a constant number of times on average, though worst-case analysis shows up to O(n) edge traversals due to pointer adjustments. The algorithm initializes with the leftmost node, finds successors by following right pointers until null, threads them, visits, and unthreads upon backtracking. Pseudocode for Morris in-order is:function morrisInorder([root](/page/Root)):

current = [root](/page/Root)

while current is not null:

if current.left is null:

visit current

current = current.right

else:

predecessor = current.left

while predecessor.right is not null and predecessor.right != current:

predecessor = predecessor.right

if predecessor.right is null:

predecessor.right = current // thread

current = current.left

else:

predecessor.right = null // unthread

visit current

current = current.right

function morrisInorder([root](/page/Root)):

current = [root](/page/Root)

while current is not null:

if current.left is null:

visit current

current = current.right

else:

predecessor = current.left

while predecessor.right is not null and predecessor.right != current:

predecessor = predecessor.right

if predecessor.right is null:

predecessor.right = current // thread

current = current.left

else:

predecessor.right = null // unthread

visit current

current = current.right