Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Complete graph

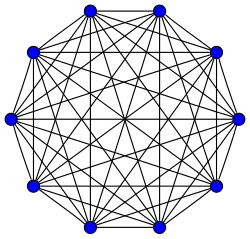

View on Wikipedia| Complete graph | |

|---|---|

K7, a complete graph with 7 vertices | |

| Vertices | n |

| Edges | |

| Radius | |

| Diameter | |

| Girth | |

| Automorphisms | n! (Sn) |

| Chromatic number | n |

| Chromatic index |

|

| Spectrum | |

| Properties | |

| Notation | Kn |

| Table of graphs and parameters | |

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a complete graph is a simple undirected graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a unique edge. A complete digraph is a directed graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a pair of unique edges (one in each direction).[1]

Graph theory itself is typically dated as beginning with Leonhard Euler's 1736 work on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg. However, drawings of complete graphs, with their vertices placed on the points of a regular polygon, had already appeared in the 13th century, in the work of Ramon Llull.[2] Such a drawing is sometimes referred to as a mystic rose.[3]

Properties

[edit]The complete graph on n vertices is denoted by Kn. Some sources claim that the letter K in this notation stands for the German word komplett,[4] but the German name for a complete graph, vollständiger Graph, does not contain the letter K, and other sources state that the notation honors the contributions of Kazimierz Kuratowski to graph theory.[5]

Kn has n(n − 1)/2 edges (a triangular number), and is a regular graph of degree n − 1. All complete graphs are their own maximal cliques. They are maximally connected as the only vertex cut which disconnects the graph is the complete set of vertices. The complement graph of a complete graph is an empty graph.

If the edges of a complete graph are each given an orientation, the resulting directed graph is called a tournament.

Kn can be decomposed into n trees Ti such that Ti has i vertices.[6] Ringel's conjecture asks if the complete graph K2n+1 can be decomposed into copies of any tree with n edges.[7] This is known to be true for sufficiently large n.[8][9]

The number of all distinct paths between a specific pair of vertices in Kn+2 is given[10] by

where e refers to Euler's constant, and

The number of matchings of the complete graphs are given by the telephone numbers

- 1, 1, 2, 4, 10, 26, 76, 232, 764, 2620, 9496, 35696, 140152, 568504, 2390480, 10349536, 46206736, ... (sequence A000085 in the OEIS).

These numbers give the largest possible value of the Hosoya index for an n-vertex graph.[11] The number of perfect matchings of the complete graph Kn (with n even) is given by the double factorial (n − 1)!!.[12]

The crossing numbers up to K27 are known, with K28 requiring either 7233 or 7234 crossings. Further values are collected by the Rectilinear Crossing Number project.[13] Rectilinear Crossing numbers for Kn are

Geometry and topology

[edit]

A complete graph with n nodes is the edge graph of an (n − 1)-dimensional simplex. Geometrically K3 forms the edge set of a triangle, K4 a tetrahedron, etc. The Császár polyhedron, a nonconvex polyhedron with the topology of a torus, has the complete graph K7 as its skeleton.[15] Every neighborly polytope in four or more dimensions also has a complete skeleton.

K1 through K4 are all planar graphs. However, every planar drawing of a complete graph with five or more vertices must contain a crossing, and the nonplanar complete graph K5 plays a key role in the characterizations of planar graphs: by Kuratowski's theorem, a graph is planar if and only if it contains neither K5 nor the complete bipartite graph K3,3 as a subdivision, and by Wagner's theorem the same result holds for graph minors in place of subdivisions. As part of the Petersen family, K6 plays a similar role as one of the forbidden minors for linkless embedding.[16] In other words, and as Conway and Gordon[17] proved, every embedding of K6 into three-dimensional space is intrinsically linked, with at least one pair of linked triangles. Conway and Gordon also showed that any three-dimensional embedding of K7 contains a Hamiltonian cycle that is embedded in space as a nontrivial knot.

Examples

[edit]Complete graphs on vertices, for between 1 and 12, are shown below along with the numbers of edges:

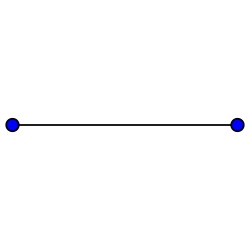

| K1: 0 | K2: 1 | K3: 3 | K4: 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| K5: 10 | K6: 15 | K7: 21 | K8: 28 |

|

|

|

|

| K9: 36 | K10: 45 | K11: 55 | K12: 66 |

|

|

|

|

See also

[edit]- Fully connected network, in computer networking

- Complete bipartite graph (or biclique), a special bipartite graph where every vertex on one side of the bipartition is connected to every vertex on the other side

- The simplex, which is identical to a complete graph of vertices, where is the dimension of the simplex.

References

[edit]- ^ Bang-Jensen, Jørgen; Gutin, Gregory (2018), "Basic Terminology, Notation and Results", in Bang-Jensen, Jørgen; Gutin, Gregory (eds.), Classes of Directed Graphs, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–34, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71840-8_1, ISBN 978-3-319-71839-2; see p. 17

- ^ Knuth, Donald E. (2013), "Two thousand years of combinatorics", in Wilson, Robin; Watkins, John J. (eds.), Combinatorics: Ancient and Modern, Oxford University Press, pp. 7–37, ISBN 978-0191630620.

- ^ Mystic Rose, nrich.maths.org, retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Gries, David; Schneider, Fred B. (1993), A Logical Approach to Discrete Math, Springer-Verlag, p. 436, ISBN 0387941150.

- ^ Pirnot, Thomas L. (2000), Mathematics All Around, Addison Wesley, p. 154, ISBN 9780201308150.

- ^ Joos, Felix; Kim, Jaehoon; Kühn, Daniela; Osthus, Deryk (2019-08-05). "Optimal packings of bounded degree trees" (PDF). Journal of the European Mathematical Society. 21 (12): 3573–3647. doi:10.4171/JEMS/909. ISSN 1435-9855. S2CID 119315954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-09. Retrieved 2020-03-09.

- ^ Ringel, G. (1963). Theory of Graphs and its Applications. Proceedings of the Symposium Smolenice.

- ^ Montgomery, Richard; Pokrovskiy, Alexey; Sudakov, Benny (2021). "A proof of Ringel's Conjecture". Geometric and Functional Analysis. 31 (3): 663–720. arXiv:2001.02665. doi:10.1007/s00039-021-00576-2.

- ^ Hartnett, Kevin (19 February 2020). "Rainbow Proof Shows Graphs Have Uniform Parts". Quanta Magazine. Archived from the original on 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ^ Hassani, M. "Cycles in graphs and derangements." Math. Gaz. 88, 123–126, 2004.

- ^ Tichy, Robert F.; Wagner, Stephan (2005), "Extremal problems for topological indices in combinatorial chemistry" (PDF), Journal of Computational Biology, 12 (7): 1004–1013, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.379.8693, doi:10.1089/cmb.2005.12.1004, PMID 16201918, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-21, retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ^ Callan, David (2009), A combinatorial survey of identities for the double factorial, arXiv:0906.1317, Bibcode:2009arXiv0906.1317C.

- ^ Oswin Aichholzer. "Rectilinear Crossing Number project". Archived from the original on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Ákos Császár, A Polyhedron Without Diagonals. Archived 2017-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, Bolyai Institute, University of Szeged, 1949

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1988), Time Travel and Other Mathematical Bewilderments, W. H. Freeman and Company, p. 140, Bibcode:1988ttom.book.....G, ISBN 0-7167-1924-X

- ^ Robertson, Neil; Seymour, P. D.; Thomas, Robin (1993), "Linkless embeddings of graphs in 3-space", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 28 (1): 84–89, arXiv:math/9301216, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1993-00335-5, MR 1164063, S2CID 1110662.

- ^ Conway, J. H.; Cameron Gordon (1983). "Knots and Links in Spatial Graphs". Journal of Graph Theory. 7 (4): 445–453. doi:10.1002/jgt.3190070410.

External links

[edit]Complete graph

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Notation

Formal Definition

In the mathematical field of graph theory, a complete graph is a simple undirected graph in which every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a unique edge.[1] This structure ensures that the graph is maximally connected among simple graphs on the same vertex set, with no additional edges possible without violating simplicity.[4] A simple graph, by definition, contains no loops (edges connecting a vertex to itself) and no multiple edges between the same pair of vertices, while the undirected nature means that edges lack direction and adjacency is symmetric.[5] In this context, the complete graph embodies the strongest form of connectivity for undirected simple graphs, where the absence of self-loops and parallel edges maintains its foundational purity.[6] The concept of a complete graph traces its early visual representation to the 13th century in the logical diagrams of Ramon Llull, a Catalan philosopher and theologian, where such interconnected figures—known as the "mystic rose"—served mnemonic and combinatorial purposes in his Ars Magna system, predating modern graph theory by centuries.[7]Notation and Conventions

The standard notation for a complete graph on vertices is , where is a positive integer representing the number of vertices.[1] This symbol, introduced in foundational graph theory texts, succinctly denotes the graph where every pair of distinct vertices is connected by a unique edge.[8] In graph theory literature, complete graphs are conventionally treated as unlabeled structures, meaning they are considered up to isomorphism rather than with fixed vertex labels.[9] All complete graphs on vertices are isomorphic to one another, as any bijection between their vertex sets preserves the adjacency relations; labeled variants, where vertices are distinguished by identifiers, are used only in contexts requiring specific vertex distinctions, such as algorithmic implementations or matrix representations.[9] The complement of is the empty graph on vertices, denoted or , which consists of isolated vertices with no edges.[10][8] This relation highlights the duality between complete and empty graphs, where the complement operation inverts the edge set while preserving the vertex set.[10] The notation serves as a fundamental building block in broader graph theory constructions, such as complete multipartite graphs.[11]Structural Properties

Number of Vertices and Edges

A complete graph is defined with vertices, where every pair of distinct vertices is connected by exactly one undirected edge, resulting in the maximum possible number of edges for a simple graph on vertices. The total number of edges is given by the binomial coefficient , which equals . This formula arises from the combinatorial principle that each edge corresponds to a unique unordered pair of vertices chosen from the available, ensuring no self-loops or multiple edges.[1][12] The sequence of edge counts for complete graphs as increases—0 for , 1 for , 3 for , 6 for , and so on—corresponds to the triangular numbers, specifically the -th triangular number . These values form the integer sequence A000217 in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS), highlighting the close relationship between complete graphs and the summation of the first natural numbers for . For example, in , there are 10 edges, matching .[1][13] In matrix representation, the adjacency matrix of is an symmetric matrix with zeros along the main diagonal (to exclude self-loops) and ones in all off-diagonal positions, formally expressed as , where is the all-ones matrix and is the identity matrix. This structure directly encodes the complete connectivity: the entry for indicates an edge between vertices and .[1]Degrees and Regularity

In a complete graph with vertices, where , each vertex is adjacent to every other distinct vertex, resulting in a degree of for every vertex.[14] This uniform degree across all vertices establishes as a regular graph of degree .[15] The regularity of follows directly from its definition: since the graph includes all possible edges between distinct vertices, no vertex is excluded from connections to any others, ensuring identical adjacency counts for all.[16] For the trivial case , the single vertex has degree 0, which is consistent with 0-regularity in the degenerate sense, though typically regularity is discussed for .[14] Applying the handshaking lemma to , the sum of all vertex degrees equals , which is twice the number of edges, confirming the lemma's validity: .[17] This equality underscores the structural balance in complete graphs, where the total degree sum aligns precisely with the exhaustive edge connections.[15]Graph-Theoretic Properties

Connectivity and Distances

In a complete graph with vertices, the vertex connectivity is , meaning that the removal of fewer than vertices leaves the graph connected, and this value equals the degree of each vertex.[18] This high connectivity reflects the graph's structure, where every vertex is adjacent to all others, ensuring robust linkage.[18] The diameter of for is 1, as the longest shortest path between any two distinct vertices is a single edge.[19] Similarly, the radius is also 1, since the eccentricity of every vertex—the maximum distance to any other vertex—is 1.[19] These properties underscore the complete graph's efficiency in traversal, with no vertex more than one step away from any other. For , the girth of is 3, determined by the smallest cycles, which are triangles formed by any three vertices.[20] This minimal girth highlights the abundance of short cycles inherent in the complete structure.Chromatic Number and Cliques

The chromatic number of the complete graph , denoted , is equal to . This follows directly from the fact that every pair of vertices in is adjacent, requiring a distinct color for each vertex to avoid adjacent vertices sharing the same color.[1] As the quintessential example of a clique, forms a complete clique on vertices, where the clique number is , representing the size of the largest clique in the graph. This structure implies that the independence number , the size of the largest independent set, is 1, since any two vertices are adjacent and thus cannot both be included in an independent set.[1][21] Complete graphs are perfect graphs, satisfying the condition that for every induced subgraph , the chromatic number equals the clique number, i.e., . In , every induced subgraph is itself a complete graph for some , where , ensuring the equality holds throughout.[22][1]Decompositions and Substructures

Edge Decompositions

A key aspect of edge decompositions in complete graphs involves partitioning the edge set into spanning subgraphs with specific structures, such as matchings or paths and cycles, which leverage the high connectivity and regularity of . For the complete graph on an even number of vertices, the edges can be decomposed into perfect matchings, known as a 1-factorization. This decomposition exists because is -regular, and each perfect matching covers all vertices exactly once, partitioning the edges completely. The construction, attributed to Walecki in the 1890s, places vertices on a circle and the remaining vertex at the center, pairing the center to one vertex and connecting opposite points on the circle for each matching, then rotating the configuration.[23] This 1-factorization relates to broader studies of resolvable balanced incomplete block designs and has applications in scheduling and network design. In contrast, for on an odd number of vertices, the edges decompose into edge-disjoint Hamiltonian cycles. Each such cycle spans all vertices, and since the graph is -regular with each cycle contributing degree 2, exactly cycles cover all edges. Walecki's construction achieves this by fixing one vertex and arranging the others in a regular -gon, forming a zigzag cycle through alternate vertices and the fixed point, then rotating the pattern times.[24] This result, also known as Lucas' theorem, dates to the late 19th century and underpins decompositions in tournament scheduling. Walecki's construction extends to decomposing into edge-disjoint Hamiltonian paths. For even order, the odd degree requires paths rather than cycles, with each path spanning edges and endpoints receiving degree 1 to balance the decomposition. The method involves a similar rotational symmetry: arrange vertices in two parallel lines of each, connect them in a serpentine pattern for one path, and rotate or reflect to generate the remaining paths. This partitions all edges exactly.[25] Recent advances in edge decompositions include the 2020 proof of Ringel's conjecture by Montgomery, Pokrovskiy, and Sudakov, establishing that any tree with edges packs edge-disjoint copies into , providing a generalization beyond paths and cycles for sufficiently large .[25]Matchings and Coverings

In complete graphs, a matching is an edge subset with no shared vertices. The size of a maximum matching in is , as edges can pair up vertices until at most one remains unpaired if is odd.[26] When is even, perfect matchings exist that saturate all vertices, and their number is given by the double factorial , which counts the ways to pair vertices sequentially: the first vertex has choices, the next unpaired has , and so on.[26] This sequence is also known as the telephone numbers and appears as OEIS A000085. An edge cover in is an edge subset incident to every vertex. By Gallai's identity, the minimum edge cover size equals , since has no isolated vertices.[26] For even , this is , achieved by any perfect matching. For odd , it is , obtained by a maximum matching of edges plus one additional edge to cover the unpaired vertex. A vertex cover in is a vertex subset incident to every edge. The independence number , as no two vertices form an independent set. By the complementary Gallai identity, the minimum vertex cover size , achieved by excluding any single vertex, whose incident edges are covered by the others.[26] Excluding two or more leaves an uncovered edge between them.Geometry and Embeddings

Planarity and Crossing Numbers

A complete graph is planar if and only if , as is the smallest non-planar complete graph and contains no proper subdivisions beyond itself that alter this property.[27] By Kuratowski's theorem, a graph is non-planar if it contains a subdivision of or as a subgraph; since is itself one of these forbidden subgraphs, all for are non-planar for the same reason. For , embeds directly as an induced subgraph, reinforcing non-planarity without requiring subdivisions.[28] The crossing number , defined as the minimum number of edge crossings in any drawing of in the plane, is zero for due to planarity. For , exact values are known for small : , achieved by drawing four vertices in convex position with the fifth inside and edges crossing once; , obtained by adding a sixth vertex to the drawing with minimal additional crossings.[29] These values form the beginning of the sequence for , cataloged as A000241 in the OEIS, with further exact determinations up to as of 2024. The Zarankiewicz problem, which seeks the maximum edges in a bipartite graph avoiding complete bipartite subgraphs , connects to crossing numbers of complete graphs via upper-bound constructions for . Specifically, Zarankiewicz's conjecture posits that for complete bipartite graphs, providing a benchmark for crossings in bipartite drawings.[30] To bound , a standard construction partitions the vertices into two nearly equal sets of sizes and , drawn on two concentric circles or layers to minimize total crossings, yielding , where is the conjectured value.[31] This yields the conjectured formula for as (Hill's conjecture, referenced by Guy), exact for and asymptotically .[32][29]Topological Properties

The complete graph serves as the 1-skeleton of the -simplex, where the vertices correspond to the simplex's vertices and the edges connect every pair, embedding the graph in -dimensional Euclidean space without crossings.[33] This realization highlights the complete graph's role in simplicial geometry, as the higher-dimensional faces of the simplex fill in the combinatorial structure beyond the mere edges.[33] A notable embedding on a non-spherical surface occurs with , whose 1-skeleton forms the Császár polyhedron, a toroidal polyhedron with 7 vertices, 21 edges, and 14 triangular faces that realizes the complete graph on a torus without self-intersections.[34] Discovered by Ákos Császár in 1949, this polyhedron demonstrates that can be embedded on a surface of genus 1, providing a polyhedral model for the torus's triangulation with the minimal number of vertices.[34] In three-dimensional space, embeddings of complete graphs exhibit intrinsic topological complexities, as established by the Conway-Gordon theorem. Specifically, every embedding of in contains a pair of disjoint cycles that form a non-trivially linked 2-component link, making intrinsically linked.[35] Similarly, every embedding of in includes a knotted Hamiltonian cycle, rendering intrinsically knotted.[35] These results, proved using algebraic invariants like linking numbers modulo 2, underscore the unavoidable knotting and linking in spatial realizations of small complete graphs.[35]Examples and Applications

Small Complete Graphs

The complete graph consists of a single vertex with no edges, representing the simplest possible graph and serving as the trivial case in graph theory.[1] It has zero edges and is often denoted as the singleton graph. Visually, it appears as an isolated point. The complete graph comprises two vertices connected by a single edge, forming the basic building block for more complex graphs.[1] With exactly one edge, it resembles a straight line segment between two points and is the smallest non-trivial complete graph. , known as the triangle graph, features three vertices where each pair is joined by an edge, resulting in three edges total and forming a closed triangular shape.[1] This graph is isomorphic to the cycle graph , emphasizing its cyclic structure without additional connections. The complete graph includes four vertices, each connected to every other, yielding six edges and embodying the tetrahedral graph, which corresponds to the skeleton of a regular tetrahedron.[1][36] It is also isomorphic to the wheel graph , though distinct from complete bipartite graphs like the utility graph , which connects vertices across two disjoint sets without intra-set edges.[37] Visually, can be drawn as a tetrahedron with vertices at the corners and edges along the faces, remaining planar unlike larger complete graphs starting from . The number of edges in a complete graph grows quadratically as , providing a quick reference for small instances as shown below.[1]| Edges in | |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 6 |

| 5 | 10 |

| 6 | 15 |

| 7 | 21 |

| 8 | 28 |

| 9 | 36 |

| 10 | 45 |

| 11 | 55 |

| 12 | 66 |