Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Permutation group.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Permutation group

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Permutation group

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

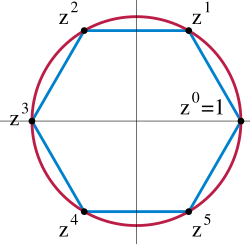

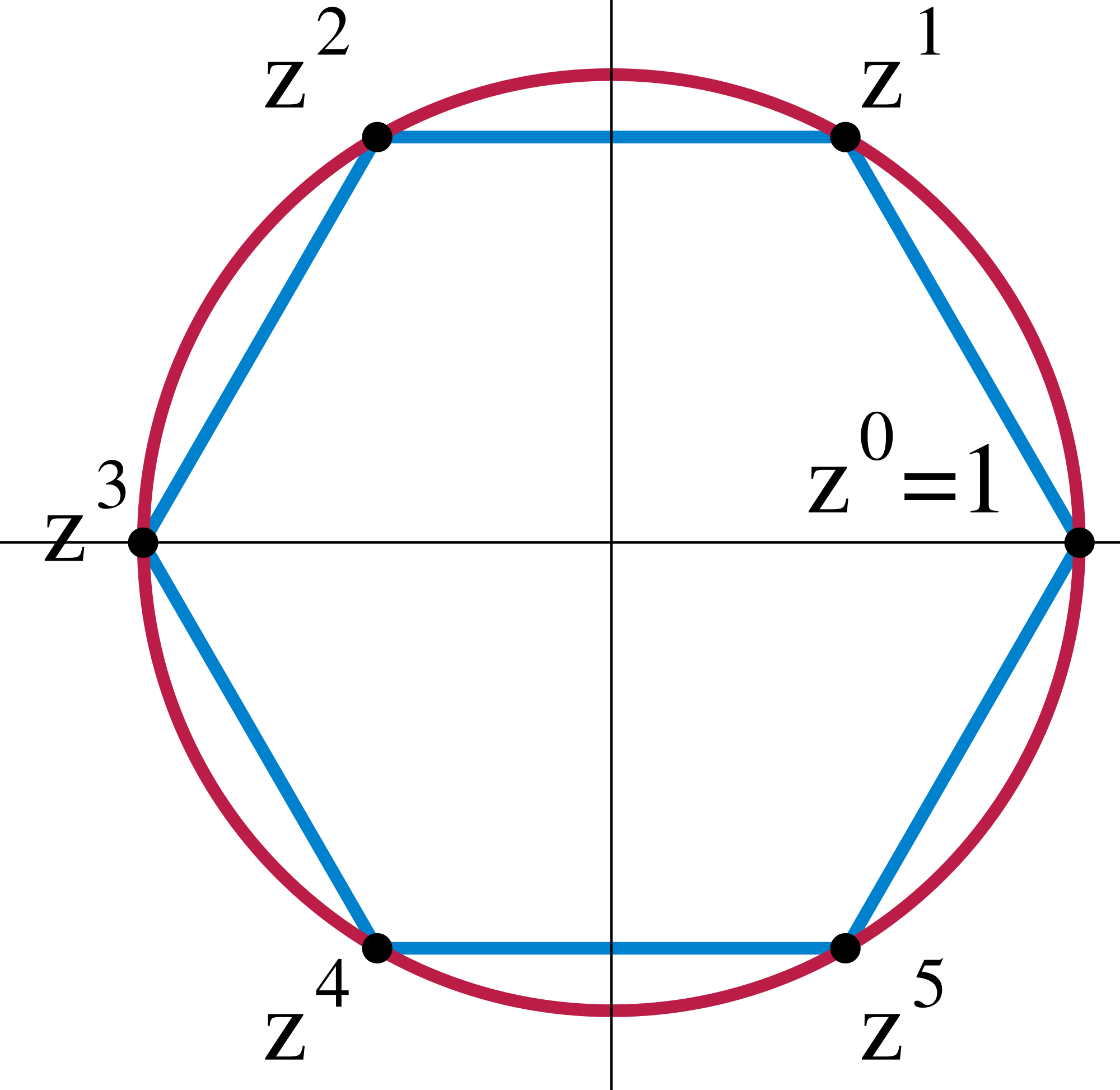

In mathematics, particularly within abstract algebra, a permutation group is a group whose elements are permutations of a given finite set and whose binary operation is the composition of such permutations, forming a subgroup of the symmetric group on that set.[1] The symmetric group , which consists of all possible permutations of a set with elements, serves as the foundational example and has order , representing the total number of ways to rearrange the elements.[2]

A key result in group theory, known as Cayley's theorem, establishes that every finite group is isomorphic to a permutation group acting regularly on itself, thereby embedding abstract groups into the concrete framework of permutations.[3] This theorem underscores the universality of permutation groups in modeling symmetries and structures across mathematics. Permutations within these groups can be classified by their sign—even or odd—based on the parity of the number of transpositions needed to express them, leading to the alternating group , the kernel of the sign homomorphism and a normal subgroup of of index 2.[4] For , is a simple group, meaning it has no nontrivial normal subgroups, which has profound implications for the classification of finite simple groups.[5]

Permutation groups play a central role in various applications, including the study of geometric symmetries, where they describe the automorphism groups of polytopes and graphs; in combinatorics, for enumerating objects under group actions via tools like Burnside's lemma; and in physics and chemistry, for analyzing molecular symmetries and identical particle systems.[6] In computational contexts, algorithms for permutation group manipulation, such as membership testing and finding strong generators, enable efficient solutions to problems in computer science and cryptography.[7] These structures also connect to Galois theory, where permutation groups of roots illuminate the solvability of polynomial equations.[6]