Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

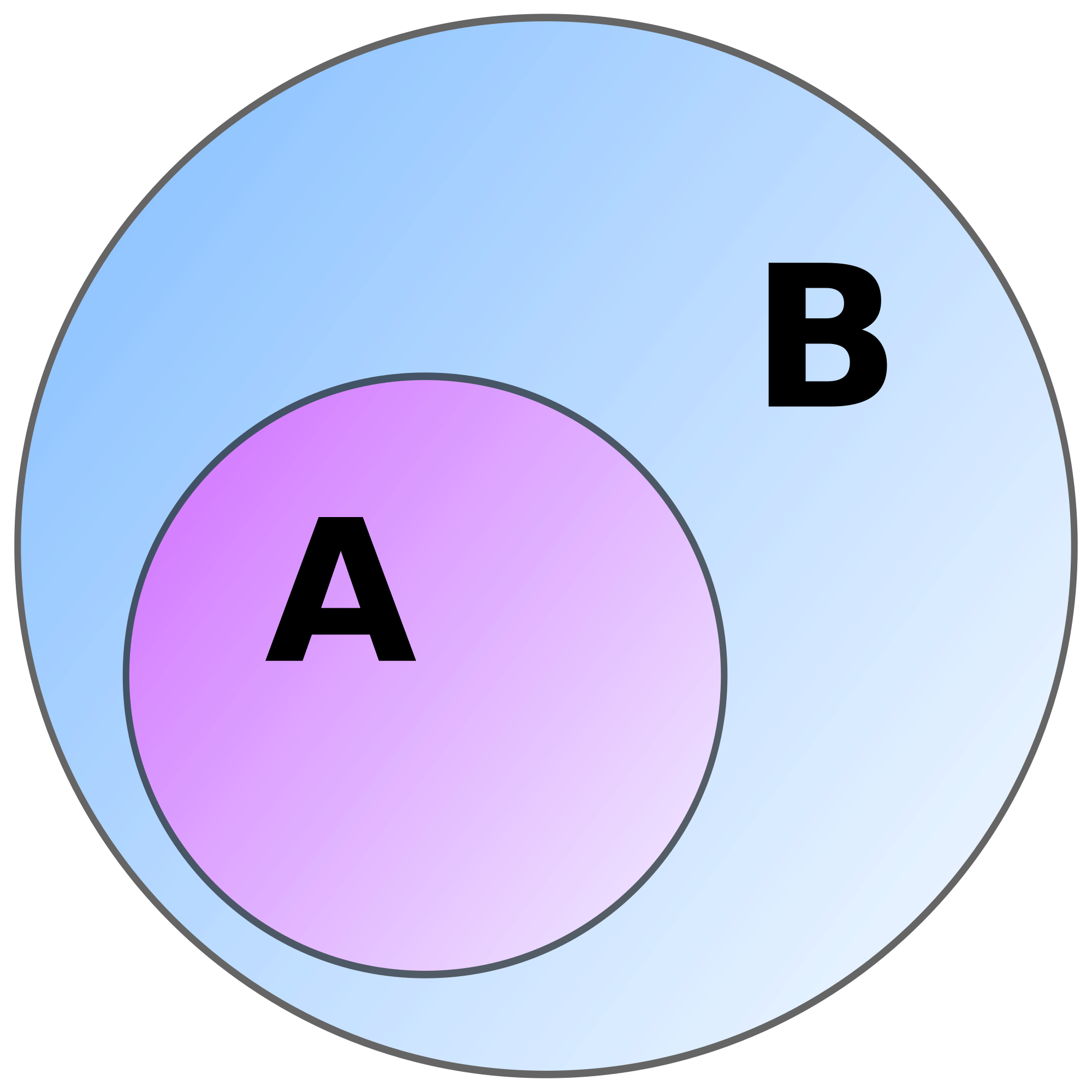

Inclusion map

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics, if is a subset of then the inclusion map is the function that sends each element of to treated as an element of

An inclusion map may also be referred to as an inclusion function, an insertion,[1] or a canonical injection.

A "hooked arrow" (U+21AA ↪ RIGHTWARDS ARROW WITH HOOK)[2] is sometimes used in place of the function arrow above to denote an inclusion map; thus:

(However, some authors use this hooked arrow for any embedding.)

This and other analogous injective functions[3] from substructures are sometimes called natural injections.

Given any morphism between objects and , if there is an inclusion map into the domain , then one can form the restriction of In many instances, one can also construct a canonical inclusion into the codomain known as the range of

Applications of inclusion maps

[edit]Inclusion maps tend to be homomorphisms of algebraic structures; thus, such inclusion maps are embeddings. More precisely, given a substructure closed under some operations, the inclusion map will be an embedding for tautological reasons. For example, for some binary operation to require that is simply to say that is consistently computed in the sub-structure and the large structure. The case of a unary operation is similar; but one should also look at nullary operations, which pick out a constant element. Here the point is that closure means such constants must already be given in the substructure.

Inclusion maps are seen in algebraic topology where if is a strong deformation retract of the inclusion map yields an isomorphism between all homotopy groups (that is, it is a homotopy equivalence).

Inclusion maps in geometry come in different kinds: for example embeddings of submanifolds. Contravariant objects (which is to say, objects that have pullbacks; these are called covariant in an older and unrelated terminology) such as differential forms restrict to submanifolds, giving a mapping in the other direction. Another example, more sophisticated, is that of affine schemes, for which the inclusions and may be different morphisms, where is a commutative ring and is an ideal of

See also

[edit]- Cofibration

- Identity function – Function that returns its argument unchanged

References

[edit]- ^ MacLane, S.; Birkhoff, G. (1967). Algebra. Providence, RI: AMS Chelsea Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.

Note that "insertion" is a function S → U and "inclusion" a relation S ⊂ U; every inclusion relation gives rise to an insertion function.

- ^ "Arrows – Unicode" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ^ Chevalley, C. (1956). Fundamental Concepts of Algebra. New York, NY: Academic Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-12-172050-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

Inclusion map

View on GrokipediaDefinition

In Set Theory

In set theory, the inclusion map, also known as the canonical injection or embedding, is a function defined whenever , such that for every .[2][1] This map simply identifies each element of the subset with itself in the larger set , effectively treating as embedded within without altering its elements.[4] The inclusion map acts as the identity function restricted to , preserving the natural membership relation between the sets while establishing a one-to-one correspondence between and its image in .[2] It is inherently injective, as distinct elements in map to distinct elements in , but it is generally not surjective unless .[1] This foundational construction underpins subset relationships in pure set theory, where no additional operations or structures are imposed on the sets. A classic example is the inclusion map , where denotes the natural numbers (e.g., {0, 1, 2, \dots}) and the integers; here, embeds the non-negative integers into the full ring of integers.[4] Another simple case is the inclusion of even integers into all integers, , with for , illustrating how the map respects the subset structure without introducing new elements.[2] The inclusion map is often denoted using the hooked arrow notation to emphasize its injective nature and the embedding aspect.[1] This concept extends naturally to settings with additional structure, such as ordered sets or topological spaces, but in pure set theory, it remains a basic tool for analyzing subset inclusions.[2]In Structured Sets

In mathematical structures, the inclusion map generalizes the set-theoretic inclusion by ensuring preservation of the defining operations, relations, or axioms. Given an algebraic structure with universe and a substructure whose universe is a subset of , the inclusion map is defined by for all . This map is a homomorphism, meaning it respects the structure: for any -ary operation in the signature, for all .[5] Similarly, for relations , if , then . This preservation ensures inherits the structure from via restriction of operations and relations to .[5] The requirement that is a homomorphism positions it within the category of the relevant structures, where objects are algebras or relational structures and morphisms are structure-preserving maps. A subset qualifies as a substructure precisely if it is closed under all operations (i.e., for ) and, for relational structures, if relations on match those induced from . The inclusion map then serves as the canonical embedding, confirming 's status as a substructure without additional mapping.[5] This builds on the pure set inclusion as the underlying function, but adds the structural fidelity.[5] A representative example occurs in vector spaces over a field . If is a subspace of a vector space , the inclusion map given by is a linear transformation, preserving vector addition and scalar multiplication: and for and . This linearity follows directly from the subspace axioms, ensuring linear combinations in remain unchanged in .[6] Unlike arbitrary embeddings, which are injective homomorphisms that may relabel elements via composition with an isomorphism, the inclusion map uses the identity function on the shared universe, providing a direct identification of elements without renaming or permutation. This naturalness makes it the standard choice for substructures, distinguishing it from more general structure-preserving injections.[5]Properties

Injectivity and Monomorphisms

An inclusion map , where , is defined by for all . This map is injective because if , then by the identity nature of the mapping on .[7] In category theory, a monomorphism is a morphism that is left-cancellative, meaning that for any object and any pair of morphisms , if , then .[8][9] Inclusion maps are always monomorphisms in standard categories such as , , and . In , every inclusion is an injective function, and monomorphisms coincide precisely with injective functions.[8][9] In , monomorphisms are injective group homomorphisms, and inclusions of subgroups satisfy this condition.[8][10] In , monomorphisms are injective continuous maps, with subspace inclusions serving as regular and strong monomorphisms when equipped with the subspace topology.[8] For example, in , the injectivity of an inclusion map directly implies it is a monomorphism, as left-cancellativity follows from the one-to-one correspondence of elements.[9] This property aligns with the broader universal property of inclusions but emphasizes their cancellative behavior in compositions.[8]Universal Property

In category theory, the inclusion map often satisfies a universal property when is constructed as a free or induced object generated by , such as in algebraic categories. Specifically, for any object in the category and any morphism that respects the relevant structure (e.g., a set map to a group when is free), there exists a unique morphism such that .[11] This property characterizes the inclusion up to isomorphism as the canonical morphism from to the universal object that "freely" completes under the category's operations. This universal property manifests as the initial object in the comma category , whose objects are morphisms from to other objects in and whose morphisms are commuting triangles over . The pair is initial, ensuring unique factorizations through for compatible maps from .[11] For instance, in the category of groups, if is a set and is the free group on with including the generators, any group homomorphism (treating as a discrete group) extends uniquely to a group homomorphism .[12] The inclusion map plays a key role in forming induced maps and restrictions across categories. Composition with induces a natural transformation on hom-sets, given by , which restricts functions or homomorphisms from to . This is essential in constructing colimits, such as pushouts where inclusions serve as legs of diagrams, ensuring compatible extensions or gluings.[12] In the category of sets, the inclusion of a subset allows extending maps from to any set by arbitrarily defining values on , though uniqueness fails unless . This reflects the coproduct structure , where is one coproduct inclusion, facilitating constructions like disjoint unions.[13] More generally, such inclusions connect to initial objects in slice categories: the pair is initial in the coslice category (or equivalently the comma category above), underscoring their role in universal approximations and free completions without delving into specific variances.[11]In Algebraic Structures

Subgroups and Homomorphisms

In group theory, given a group and a subgroup , the inclusion map is defined by for all . This map is a group homomorphism because the binary operation on is the restriction of the operation on , ensuring that for all .[14] The inclusion map is injective, since implies , and its image exactly, providing an embedding that identifies the subgroup with its isomorphic copy within .[15] A representative example is the inclusion of the cyclic subgroup of even integers into the additive group of all integers, where for ; this preserves addition as . In the context of quotient groups, the inclusion map aids in characterizing normal subgroups through kernels of homomorphisms. For a normal subgroup , the inclusion has trivial kernel, and pairs with the canonical projection (whose kernel is ) to form the short exact sequence , illustrating how normality enables the quotient structure while the inclusion embeds faithfully.[16]Subrings and Ideals

In ring theory, an inclusion map arises naturally when one ring is a subring of another. If is a subring of a ring , the inclusion map is defined by for all . This map is a ring homomorphism because it preserves the ring operations inherited from : and . Since subrings share the multiplicative identity of the ambient ring, , ensuring the homomorphism respects the unit.[17][18] A classic example is the inclusion of the ring of integers into the field of rational numbers , where serves as a subring under the standard addition and multiplication. Here, maps each integer to itself, preserving all operations and the identity 1. This inclusion highlights how integer arithmetic embeds into the broader structure of rational numbers, facilitating extensions in algebraic number theory.[17] While ideals are not typically subrings (as they often lack the multiplicative unit unless ), inclusions involving ideals connect to quotient rings through homomorphisms. Specifically, if are ideals of , the inclusion (viewed in the context of the quotient map ) induces a surjective ring homomorphism with kernel , reflecting the lattice structure of ideals and their quotients. This relationship underscores the role of inclusion maps in the correspondence theorem for rings.[19]In Topology

Continuous Maps

In topology, the inclusion map , where is a subset of a topological space , is defined by for all , and is equipped with the subspace topology .[20] This map is continuous by construction, as it ensures that the topological structure of is compatible with that of .[21] To verify continuity, consider an arbitrary open set in . The preimage under is , which is open in the subspace topology by definition.[21] Since every open set in has a preimage that is open in , satisfies the continuity condition. The subspace topology, also known as the relative topology, thus inherits openness from intersections with open sets in , preserving the local properties of the ambient space on .[20] A representative example is the inclusion , where has the standard topology generated by open intervals. Open sets in are of the form for and open intervals in , such as , which remains open in the subspace topology.[20] This illustrates how the inclusion map maintains continuity while inducing the expected Euclidean structure on the subspace.[22]Embeddings of Spaces

In topology, an inclusion map , where is a subset of a topological space equipped with the subspace topology, is a topological embedding if it is a homeomorphism onto its image endowed with the subspace topology induced from .[23] This means is continuous, injective, and the inverse map from to is also continuous with respect to the subspace topology.[24] By construction, every such inclusion map satisfies this property, as the subspace topology on is defined precisely to make a homeomorphism onto its image.[24] The inclusion map is continuous for any subset , but additional properties like being an open or closed map depend on the nature of . Specifically, is an open map if and only if is an open subset of , meaning that the image of every open set in (under the subspace topology) is open in .[25] Conversely, is a closed map if is a closed subset of . In general, for to behave as an open map onto saturated sets or under other conditions, must satisfy corresponding topological criteria, such as being saturated with respect to certain open covers, ensuring the embedding preserves openness in the image.[23] A classic example is the inclusion of the unit circle into , where carries the subspace topology. This map is a topological embedding, as it is a homeomorphism onto its image, the unit circle itself, preserving the topological structure of .[23] Unlike an immersion, which requires only a local homeomorphism onto the image (typically in the context of differentiable manifolds), a topological embedding demands a global homeomorphism to the image, ensuring no topological distortions occur across the entire space.[26]Applications

In Homotopy Theory

In homotopy theory, the inclusion map of a subspace into a topological space induces group homomorphisms on the th homotopy groups for each , where basepoints are preserved under the inclusion. These induced maps capture how homotopy classes in extend or relate to those in . Analogously, on singular homology, the inclusion induces chain maps that yield homomorphisms for each .[27] A fundamental result states that if is a deformation retract of , then is a homotopy equivalence, so is an isomorphism on every homotopy group for . This holds because a deformation retract provides a homotopy such that , , and for all , implying the retraction composed with is homotopic to the identity on , and vice versa relative to . The same applies to homology, where induces isomorphisms under these conditions.[27] For instance, the inclusion of the equator induces the zero homomorphism on , as loops on the equator bound hemispheres in . On higher homotopy groups for , , so yields the unique homomorphism from the trivial group to , which is an isomorphism if and only if (though for ). This example illustrates how inclusions can detect non-trivial extensions in higher dimensions.[27] Inclusion maps feature prominently in the long exact sequence of the homotopy pair : which is exact, allowing computation of relative homotopy groups via the kernel and image of . A parallel long exact sequence exists in homology: These sequences exploit inclusions to relate absolute and relative invariants, as in CW complexes where the inclusion of the -skeleton induces isomorphisms on for .[27]In Scheme Theory

In scheme theory, inclusion maps manifest as closed immersions, which are morphisms of schemes such that induces a homeomorphism from onto a closed subset of , and the induced map on structure sheaves is surjective.[28] For affine schemes, a closed immersion corresponds precisely to a surjective ring homomorphism , such as when for some ideal .[28] This surjection defines the kernel ideal sheaf on , which is quasi-coherent, ensuring the embedding captures the structure of the closed subscheme.[28] Closed immersions possess key properties that underscore their role as inclusions: they are monomorphisms in the category of schemes, meaning they are injective on points and faithfully reflect the scheme structure without isomorphisms beyond the identity.[29] When defined via quotient rings, these immersions are affine morphisms, preserving the affine nature of the source scheme within the target.[28] Moreover, the ideal sheaf associated to the immersion allows for a precise description of the closed subscheme as the zero set of that ideal, enabling local computations on affine opens.[28] A representative example is the closed immersion , induced by the surjection .[28] This embeds the spectrum of the dual numbers as a closed subscheme of the affine line , where the unique prime ideal of maps to the origin, incorporating a nilpotent element with ; geometrically, it models an infinitesimal thickening of the point at the origin, often interpreted as a "double point" on the line.[30] Closed immersions play a crucial role in defining closed subschemes and facilitating the construction of schemes through gluing. A closed subscheme of a scheme is given by a closed immersion , allowing the specification of subscheme structures via ideals.[28] In gluing constructions, pushouts along closed immersions exist in the category of schemes—for instance, given a closed immersion and a morphism , the resulting pushout forms a scheme that effectively glues and along the shared closed subscheme , preserving scheme-theoretic properties like separatedness.[31] This mechanism is fundamental for building composite schemes from simpler components while respecting their closed substructures.[28]References

- https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/Monomorphism_iff_injective_in_the_category_of_groups