Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

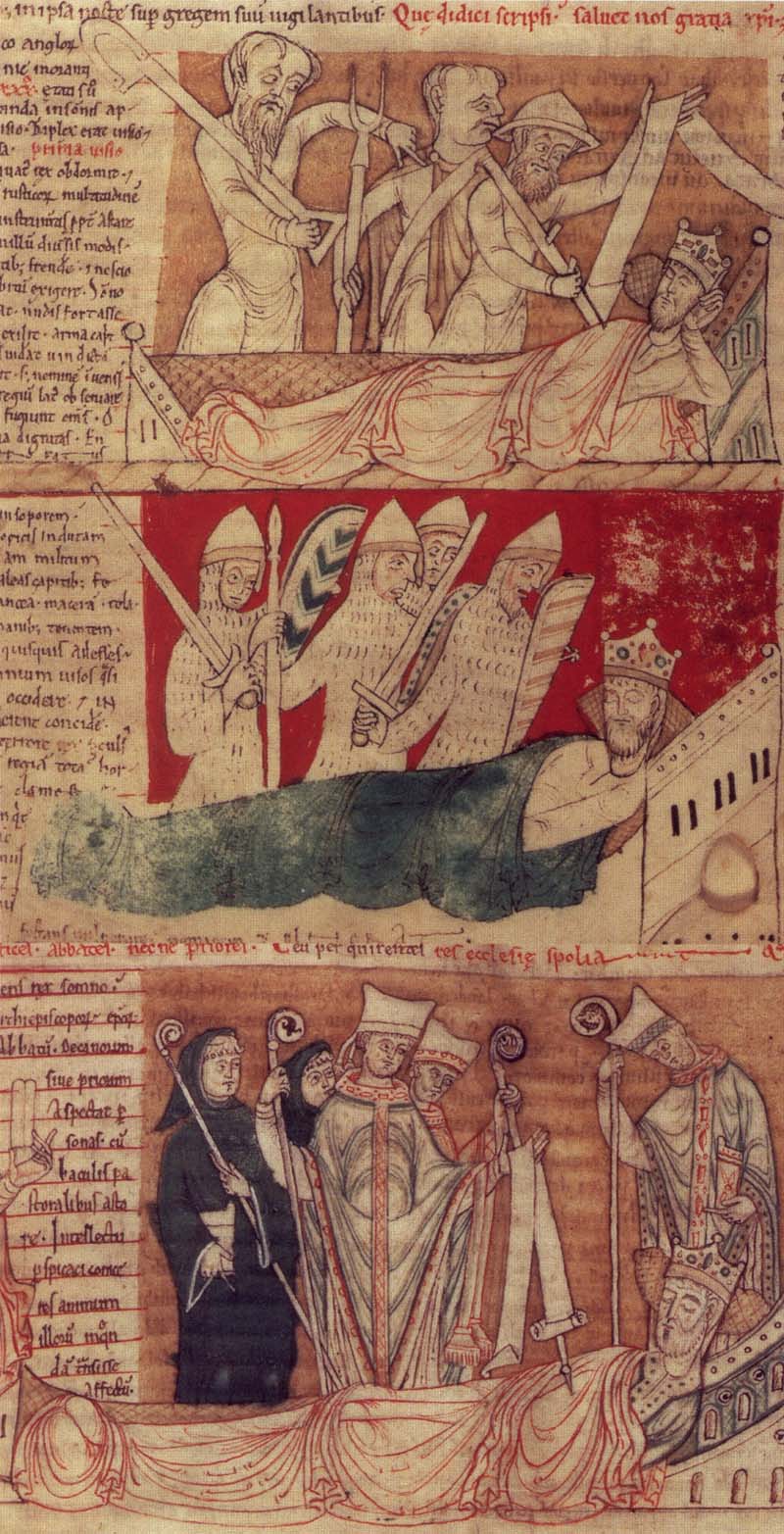

John of Worcester

View on Wikipedia

John of Worcester (died c. 1140) was an English monk and chronicler who worked at Worcester Priory. He is now usually held to be the author of the Chronicon ex Chronicis.

Works

[edit]John of Worcester's principal work was the Chronicon ex Chronicis (Latin for "Chronicle from Chronicles") or Chronicle of Chronicles (Chronica Chronicarum), also known as John of Worcester's Chronicle or Florence of Worcester's Chronicle. The Chronicon ex Chronicis is a world history which begins with the Creation and ends in 1140. The chronological framework of the Chronicon was presented by the chronicle of Marianus Scotus (d. 1082). A great deal of additional material, particularly relating to English history, was grafted onto it. These include a rendition of the Genealogia Lindisfarorum (Latin for "Genealogy of the people of Lindisfarne"), a putative genealogical list found in this and some other medieval manuscripts.

Authorship

[edit]The greater part of the work, up to 1117 or 1118, was formerly attributed to Florence of Worcester on the basis of the entry for his death under the year 1118, which credits his skill and industry for making the chronicle such a prominent work.[1] In this view, the other Worcester monk, John, merely wrote the final part of the work. However, there are two main objections against the ascription to Florence. First, there is no change of style in the Chronicon after Florence's death, and second, certain sections before 1118 rely to some extent on the Historia Novorum ("History of New Things") of Eadmer of Canterbury, which was completed sometime in the period 1121–1124.[2]

The prevalent view today is that John of Worcester was the principal author and compiler. He is explicitly named as the author of two entries for 1128 and 1138, and two manuscripts (CCC MS 157 and the Chronicula) were written in his hand. He was seen working on it at the behest of Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester, when the Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis visited Worcester:

Ioannes Wigornensis a puero monachus, natione Anglicus, moribus et eruditione uenerandus, in his quæ Mariani Scotti cronicis adiecit, de rege Guillelmo et de rebus quæ sub eo uel sub filiis eius Guillelmo Rufo et Henrico usque hodie contigerunt honeste deprompsit. [...] Quem prosecutus Iohannes acta fere centum annorum contexuit, iussuque uenerabilis Wlfstani pontificis et monachi supradictis cronicis inseruit in quibus multa de Romanis et Francis et Alemannis aliisque gentibus quæ agnouit [...]. "John, an Englishman by birth who entered the monastery of Worcester as a boy and won great repute for his learning and piety, continued the chronicle of Marianus Scotus and carefully recorded the events of William's reign and of his sons William Rufus and Henry up to the present. [...] John, at the command of the venerable Wulfstan bishop and monk [d. 1095], added to these chronicles [i.e. of Marianus Scotus] events of about a hundred years, by inserting a brief and valuable summary of many deeds of the Romans and Franks, Germans and other peoples whom he knew [...]."[3]

Manuscripts

[edit]The Chronicon survives in five manuscripts (and a fragment on a single leaf):

- MS 157 (Oxford, Corpus Christi College). The principal manuscript, working copy used by John.

- MS 502 (Dublin, Trinity College).

- MS 42 (Lambeth Palace Library).

- MS Bodley 297 (Oxford, Bodleian Library).

- MS 92 (Cambridge, Corpus Christi College),[5] continued with text from John of Taxster's Bury Chronicle.[6]

In addition, there is the Chronicula, a minor chronicle based on the Chronicon proper: MS 503 (Dublin, Trinity College), written by John up to 1123.

Sources for English history

[edit]For the body of material dealing with early English history, John is believed to have used a number of sources, some of which are now lost:

- unknown version(s) of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, possibly in Latin translation. John may have shared a lost source with William of Malmesbury, whose Gesta Regum Anglorum ("Deeds of the Kings of the English") includes similar material not found in other works.

- Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica ("Ecclesiastical History") up to 731

- Asser, Vita Ælfredi ("Life of Alfred")

- Hagiographical works on 10th and 11th-century saints

- Lives of St Dunstan (by author "B"), Adelard and Osbern

- Byrhtferth, Life of St. Oswald

- Osbern of Canterbury, Life of St Ælfheah

- Eadmer of Canterbury, Historia Novorum (1066–1122)

- Accounts by contemporaries and local knowledge

Editions and translations

[edit]- Darlington, Reginald R. and P. McGurk, eds. P. McGurk and Jennifer Bray (trs.). The Chronicle of John of Worcester: The Annals from 450–1066. Vol II. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford: 1995.

- McGurk, P. ed. and tr., The Chronicle of John of Worcester: The Annals from 1067 to 1140 with the Gloucester Interpolations and the Continuation to 1141. Vol III. OMT. Oxford, 1998.

- McGurk, P. and Woodman, D. A., ed. and trans., (2024), The Chronicle of John of Worcester: Volume IV, Chronicula, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 978-0198916147

- Thorpe, Benjamin, ed. (1848–1849), Florentii Wigorniensis Monachi Chronicon ex Chronicis... [Florence of Worcester's Chronicle from Chronicles] (in Latin), London.

- Stevenson, J. (tr.). Church Historians of England. 8 vols: vol. 2.1. London, 1855. 171–372.

- Forester, Thomas, ed. (1854), The Chronicle of Florence of Worcester with the Two Continuations Comprising Annals of English History from the Departure of the Romans to the Reign of Edward I., Bohn's Antiquarian Library, London: Henry G. Bohn

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link). - Weaver, J. R. H., ed. (1908) The Chronicle of John of Worcester, 1118–1140: being the continuation of the Chronicon ex Chronicis of Florence of Worcester. Oxford: Clarendon Press Edition on Archive.org

References

[edit]- ^ [...] huius subtili scienta et studiosi laboris industria, preeminet cunctis haec chronicarum chronica.

- ^ Gransden, Historical Writing, p. 144.

- ^ Orderic Vitalis, Historia Ecclesiastica, Book III, ed. and tr. Chibnall, p. 186-9.

- ^ John of Worcester (1128). The Chronicle of John of Worcester (MS 157 ed.). Corpus Christi College, Oxford: John of Worcester. p. 380.

- ^ "Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 092: John of Worcester OSB ('Florence of Worcester'), Chronica Chronicarum", Parker Library on the Web, Peterborough: St Peter's Abbey, c. 1325.

- ^ Thorpe (1848–1849), p. xii.

Further reading

[edit]- Brett, Martin. "John of Worcester and his contemporaries." In The Writing of History in the Middle Ages: Essays Presented to R.W. Southern, ed. by R.H.C. Davis and J.M. Wallace Hadrill. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981. 101-26.

- Brett, Martin, "John, monk of Worcester." In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge, et al. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0

- Cleaver, L. (2022). "The Making of the Worcester Chronicle". In Tinti, F.; Woodman, D. (eds.). Constructing History Across the Norman Conquest. York: York Medieval Press. pp. 174–199.

- Gransden, Antonia. Historical writing in England c. 550 to 1307. Vol 1. London, 1974. 143–8.

- O'Donnell, Thomas. "Identities in Community: Literary Culture and Memory at Worcester." In Constructing History Across the Norman Conquest: Worcester, c.1050-c.1150, ed. by Francesca Tinti and D. A. Woodman. York: York Medieval Press, 2022. 31–60.

- Orderic Vitalis, Historia Ecclesiastica, ed. and tr. Marjorie Chibnall, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis. 6 volumes. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford, 1968–1980. ISBN 0-19-820220-2.