Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coventry

View on Wikipedia

Coventry (/ˈkɒvəntri/ ⓘ KOV-ən-tree[5] or rarely /ˈkʌv-/ KUV-)[6] is a cathedral city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands county, in England, on the River Sherbourne. Coventry had been a large settlement for centuries. Founded in the early Middle Ages, its city status was formally recognised in a charter of 1345.[7] The city is governed by Coventry City Council, and the West Midlands Combined Authority.[8]

Key Information

Formerly part of Warwickshire until 1451, and again from 1842 to 1974, Coventry had a population of 345,324 at the 2021 census,[1] making it the tenth largest city in England and the 13th largest in the United Kingdom.[9]

It is the second largest city in the West Midlands region, after Birmingham, from which it is separated by an area of green belt known as the Meriden Gap; and is the third largest in the wider Midlands after Birmingham and Leicester. The city is part of a larger conurbation known as the Coventry and Bedworth Urban Area, which in 2021 had a population of 389,603.[10]

Coventry is 19 miles (31 km) east-south-east of Birmingham, 24 miles (39 km) south-west of Leicester, 10 miles (16 km) north of Warwick and 94 miles (151 km) north-west of London. Coventry is also the most central city in England, being only 12 miles (19 km) south-west of the country's geographical centre in Leicestershire.[11][12]

Coventry became an important and wealthy city of national importance during the Middle Ages. Later it became an important industrial centre, becoming home to a large bicycle industry in the 19th century. In the 20th century, it became a major centre of the British motor industry; this made it a target for German air raids during the Second World War, and in November 1940, much of the historic city centre was destroyed by a large air raid.

The city was rebuilt after the war, and the motor industry thrived until the mid-1970s. However, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, Coventry was in an economic crisis, with one of the country's highest levels of unemployment due to major plant closures and the collapse of the respective local supply-chain. In recent years, it has seen regeneration and an increase in population. The city also has three universities: Coventry University in the city centre, the University of Warwick on the southern outskirts and the smaller private Arden University with its headquarters close to Coventry Airport. In addition, Coventry was awarded UK City of Culture for 2021.[13][14][15]

History

[edit]Origins and toponymy

[edit]The Romans founded a large fort on the outskirts of what is now Coventry at Baginton, next to the River Sowe; it has been excavated and partially reconstructed in modern times and is known as the Lunt Fort. The fort was probably constructed around AD 60 in connection with the Boudican revolt and then inhabited sporadically until around 280 AD.[16]

The origins of the present settlement are obscure, but Coventry probably began as an Anglo-Saxon settlement. Although there are various theories of the origin of the name, the most widely accepted is that it was derived from Cofa's tree; derived from a Saxon landowner called Cofa, and a tree which might have marked either the centre or the boundary of the settlement.[17]

Medieval

[edit]

Around c. AD 700 a Saxon nunnery was founded here by St Osburga,[18] which was later left in ruins by King Canute's invading Danish army in 1016.[17] Leofric, Earl of Mercia and his wife Lady Godiva built on the remains of the nunnery and founded a Benedictine monastery in 1043 dedicated to St Mary.[19][20] It was during this time that the legend of Lady Godiva riding naked on horseback through the streets of Coventry, to protest against unjust taxes levied on the citizens of Coventry by her husband, was alleged to have occurred. Although this story is regarded as a myth by modern historians, it has become an enduring part of Coventry's identity.[21]

A market was established at the abbey gates and the settlement expanded. At the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066, Coventry was probably a modest sized town of around 1,200 inhabitants, and its own minster church.[17]

Coventry Castle was a motte and bailey castle in the city. It was built in the early 12th century by Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester. Its first known use was during The Anarchy when Robert Marmion, a supporter of King Stephen, expelled the monks from the adjacent priory of Saint Mary in 1144, and converted it into a fortress from which he waged a battle against the castle which was held by the Earl. Marmion perished in the battle.[22] It was demolished in the late 12th century.[23] St Mary's Guildhall was built on part of the site. It is assumed the name "Broadgate" comes from the area around the castle gates.

The Bishops of Lichfield were often referred to as the Bishops of Coventry and Lichfield, or Lichfield and Coventry (from 1102 to 1541), and in the medieval period Coventry was a major centre of pilgrimage of religion.[24] The Benedictines, Carthusians, Carmelites and Franciscans all had religious houses in the city of Coventry. The Carthusian Priory of St Anne was built between 1381 and 1410 with royal patronage from King Richard II and his queen Anne of Bohemia[25] Coventry has some surviving religious artworks from this time, such as the doom painting at Holy Trinity Church which features Christ in judgement, figures of the resurrected, and contrasting images of Heaven and Hell.[26]

By the 13th century, Coventry had become an important centre of the cloth trade, especially blue cloth dyed with woad and known as Coventry blue.[27] Throughout the Middle Ages, it was one of the largest and most important cities in England, which at its Medieval height in the early 15th century had a population of up to 10,000, making it the most important city in the Midlands, and possibly the fourth largest in England behind London, York and Bristol.[28] Reflecting its importance, in around 1355, work began on a defensive city wall, which, when finally finished around 175 years later in 1530, measured 2.25 miles (3.62 km) long, at least 12 feet (3.7 m) high, and up to 9 feet (2.7 m) thick, it had two towers and twelve gatehouses. Coventry's city walls were described as one of the wonders of the late Middle Ages.[29] Today, Swanswell Gate and Cook Street Gate are the only surviving gatehouses and they stand in the city centre framed by Lady Herbert's Garden.[30]

Coventry claimed the status of a city by ancient prescriptive usage, and was granted a charter of incorporation and coat of arms by King Edward III in 1345. The motto "Camera Principis" (the Prince's Chamber) refers to Edward, the Black Prince.[31] In 1451 Coventry became a county in its own right, a status it retained until 1842, when it was reincorporated into Warwickshire.[32][33]

Coventry's importance during the Middle Ages was such, that on a two occasions a national Parliament was held there, as well as a number of Great Councils.[34] In 1404, King Henry IV summoned a parliament in Coventry as he needed money to fight rebellion, which wealthy cities such as Coventry lent to him. During the Wars of the Roses, the Royal Court was moved to Coventry by Margaret of Anjou, the wife of Henry VI, as she believed that London had become too unsafe. On several occasions between 1456 and 1459 parliament was held in Coventry, including the so-called Parliament of Devils.[35] For a while Coventry served as the effective seat of government, but this would come to an end in 1461 when Edward IV was installed on the throne.[36][37]

Tudor period

[edit]

In 1506 the draper Thomas Bond founded Bond's Hospital, an almshouse in Hill Street, to provide for 10 poor men and women.[38][39] This was followed in 1509 with the founding of another almshouse, when the wool merchant William Ford founded Ford's Hospital and Chantry on Greyfriars' Lane, to provide for 5 poor men and their wives.[40][41][42]

Throughout the Middle Ages Coventry had been home to several monastic orders and the city was badly hit by Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries. Between 1539 and 1542, monasteries, priories and other properties belonging to the Carmelites, Greyfriars, Benedictines and Carthusians, were either sold off or dismantled. The greatest loss to the city was of Coventry's first Cathedral, St Mary's Priory and Cathedral which was mostly demolished, leaving only ruins, making it the only English Cathedral to be destroyed during the dissolution. Coventry would not have another Cathedral until 1918, when the parish church of St Michael was elevated to Cathedral status, and it was itself destroyed by enemy bombing in 1940. Coventry therefore has had the misfortune of losing its Cathedral twice in its history.[43]

William Shakespeare, from nearby Stratford-upon-Avon, may have witnessed plays in Coventry during his boyhood or 'teens', and these may have influenced how his plays, such as Hamlet, came about.[44]

Civil War and aftermath

[edit]

During the English Civil War Coventry became a bastion of the Parliamentarians: In August 1642, a Royalist force led by King Charles I attacked Coventry. After a two-day battle, however, the attackers were unable to breach the city walls, and the city's garrison and townspeople successfully repelled the attack, forcing the King's forces to withdraw. During the Second Civil War many Scottish Royalist prisoners were held in Coventry; it is thought likely that the idiom "sent to Coventry", meaning to ostracise someone, derived from this period, owing to the often hostile attitude displayed towards the prisoners by the city folk.[45]

Following the restoration of the monarchy, as punishment for the support given to the Parliamentarians, King Charles II ordered that the city's walls be slighted (damaged and made useless as defences) which was carried out in 1662.[46]

Industrial age

[edit]

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, silk ribbon weaving and watch and clock making became Coventry's staple industries. In the 1780s, the silk ribbon weaving industry was estimated to employ around 10,000 weavers in Coventry, and its surrounding towns like Bedworth and Nuneaton. Coventry's growth was aided by the opening of the Coventry Canal in 1769, which gave the city a connection to the growing national canal network. Nevertheless, during the 18th century, Coventry lost its status as the Midlands' most important city to nearby Birmingham, which overtook Coventry in size.[47] During the same period, Coventry became one of the three main British centres of watch and clock manufacture and ranked alongside Prescot, in Lancashire and Clerkenwell in London.[48][49] By the 1841 census the population was 30,743.[50]

By the 1850s, Coventry had overshadowed its rivals to become the main centre of British watch and clock manufacture, which by that time employed around 2,000 people. The watch and clock industry produced a pool of highly skilled craftsmen, who specialised in producing precision components,[51] and the Coventry Watchmakers' Association was founded in 1858.[52]

As the city prospered industrially in the 18th and early 19th centuries, several Coventry newspapers were founded. These include Jopson's Coventry Mercury, first issued by James Jopson of Hay Lane in 1741; the Coventry Gazette and Birmingham Chronicle, first published in 1757; the Coventry Herald, first published in 1808; the Coventry Observer, first published in 1827; and the Coventry Advertiser, first published in 1852.[52]

The ribbon weaving and clock industries both rapidly collapsed after 1860, due to cheap imports following the Cobden–Chevalier free trade treaty, which flooded the market with cheaper French silks, and Swiss Made clocks and watches. For a while, this caused a devastating slump in Coventry's economy.[53]

A second wave of industrialisation, however, began soon after. Coventry's pool of highly skilled workers attracted James Starley, who set up a company producing sewing machines in Coventry in 1861. Within a decade, he became interested in bicycles, and developed the penny-farthing design in 1870. His company soon began producing these bicycles, and Coventry soon became the centre of the British bicycle industry. Further innovation came from Starley's nephew, John Kemp Starley, who developed the Rover safety bicycle, the first true modern bicycle with two equal-sized wheels and a chain drive in 1885.[54] By the 1890s Coventry had the largest bicycle industry in the world, with numerous manufacturers, however bicycle manufacture went into steady decline from then on, and ended entirely in 1959, when the last bicycle manufacturer in the city relocated.[55]

By the late-1890s, bicycle manufacture began to evolve into motor manufacture. The first motor car was made in Coventry in 1897, by the Daimler Company. Before long Coventry became established as one of the major centres of the British motor industry.[54] In the early-to-mid 20th century, a number of famous names in the British motor industry became established in Coventry, including Alvis, Armstrong Siddeley, Daimler, Humber, Jaguar, Riley, Rootes, Rover, Singer, Standard, Swift and Triumph.[56] Thanks to the growth of the car industry attracting workers, Coventry's population doubled between 1901 and 1911.[52]

For most of the early-20th century, Coventry's economy boomed; in the 1930s, a decade otherwise known for its economic slump, Coventry was noted for its affluence. In 1937 Coventry topped a national purchasing power index, designed to calculate the purchasing power of the public.[57]

Great War (1914–1918)

[edit]

Many Coventry factories switched production to military vehicles, armaments and ammunitions during the Great War. Approximately 35,000 men from Coventry and Warwickshire served during the First World War,[58] so most of the skilled factory workers were women drafted from all over the country.[59] Due to the importance of war production in Coventry it was a target for German zeppelin attacks and defensive anti-aircraft guns were established at Keresley and Wyken Grange to protect the city.[60]

In June 1921, the War Memorial Park was opened on the former Styvechale Common[61] to commemorate the 2587 soldiers[62] from the city who lost their lives in the war. The War Memorial was designed by Thomas Francis Tickner and is a Grade II* building.[63] It was unveiled by Earl Haig in 1927, with a room called the Chamber of Silence inside the monument holding the roll of honour.[64] Soldiers who lost their lives in recent conflicts have been added to the roll of honour over the years.[65]

Urban expansion and development

[edit]

With many of the city's older properties becoming increasingly unfit for habitation, the first council houses were let to their tenants in 1917. With Coventry's industrial base continuing to soar after the end of the Great War in 1918, numerous private and council housing developments took place across the city in the 1920s and 1930s to provide housing for the large influx of workers who came to work in the city's booming factories. The areas which were expanded or created in this development included Radford, Coundon, Canley, Cheylesmore and Stoke Heath.[66]

As the population grew, the city boundaries underwent several expansions, in 1890, 1928, 1931 and 1965,[67] and between 1931 and 1940 the city grew by 36%.[68]

The development of a southern by-pass around the city, starting in the 1930s and being completed in 1940, helped deliver more urban areas to the city on previously rural land. In the 1910s plans were created to redevelop Coventry's narrow streets and by the 1930s the plans were put into action with Coventry's medieval street of Butcher Row being demolished.[69] even before the war, the plans had been put in place to destroy the medieval character of Coventry.[70]

The London Road Cemetery was designed by Joseph Paxton on the site of a former quarry to meet the needs of the city.

German bombing of Coventry

[edit]

Coventry suffered severe bomb damage during the Second World War. The most severe was a massive Luftwaffe air raid that the Germans called Operation Moonlight Sonata. The raid, which involved more than 500 aircraft, started at 7pm on 14 November 1940 and carried on for 11 hours into the morning of 15 November. The raid led to severe damage to large areas of the city centre and to Coventry's historic cathedral, leaving only a shell and the spire. More than 4,000 houses were damaged or destroyed, along with around three quarters of the city's industrial plants. Between 380 and 554 people were killed, with thousands injured and homeless.[71]

Aside from London, Hull and Plymouth, Coventry suffered more damage than any other British city during the Luftwaffe attacks, with huge firestorms devastating most of the city centre. The city was probably targeted owing to its high concentration of armaments, munitions, aircraft and aero-engine plants which contributed greatly to the British war effort, although there have been claims that Hitler launched the attack as revenge for the bombing of Munich by the RAF six days before the Coventry Blitz and chose the Midlands city because its medieval heart was regarded as one of the finest in Britain.[72] Following the raids, the majority of Coventry's historic buildings were demolished by a council who saw no need of them in a modern city, although some of them could have been repaired and some of those demolished were unaffected by the bombing.

Post-Second World War

[edit]

Redevelopment

[edit]In the post-war years Coventry was largely rebuilt under the general direction of the Gibson Plan, gaining a new pedestrianised shopping precinct (the first of its kind in Europe on such a scale) and in 1962 Sir Basil Spence's much-celebrated new St Michael's Cathedral (incorporating one of the world's largest tapestries) was consecrated. Its prefabricated steel spire (flèche) was lowered into place by helicopter.[73]

Further housing developments in the private and public sector took place after the Second World War, partly to accommodate the growing population of the city and also to replace condemned and bomb damaged properties. Several new suburbs were constructed in the post-war period, including Tile Hill, Wood End, and Stoke Aldermoor.[73]

Boom and bust

[edit]

Coventry's motor industry boomed during the 1950s and 1960s and Coventry enjoyed a 'golden age'. In 1960 over 81,000 people were employed in the production of motor vehicles, tractors and aircraft in Coventry.[56] During this period the disposable income of Coventrians was amongst the highest in the country and both the sports and the arts benefited. A new sports centre, with one of the few Olympic standard swimming pools in the UK, was constructed and Coventry City Football Club reached the First Division of English Football. The Belgrade Theatre (named in recognition of a gift of timber from the Yugoslavian capital city[52]) was also constructed along with the Herbert Art Gallery. Coventry's pedestrianised Precinct shopping area came into its own and was considered one of the finest retail experiences outside London. In 1965 the new University of Warwick campus was opened to students, and rapidly became one of the country's leading higher-education institutions.[73]

Coventry's large industrial base made it attractive to the wave of Asian and Caribbean immigrants who arrived from Commonwealth colonies after 1948. In 1950, one of Britain's first mosques—and the very first in Coventry—was opened on Eagle Street to serve the city's growing Pakistani community.[74]

The 1970s, however, saw a decline in the British motor industry and Coventry suffered particularly badly, especially towards the end of that decade. By the 1970s, most of Coventry's motor companies had been absorbed and rationalised into larger companies, such as British Leyland and Chrysler which subsequently collapsed. The early 1980s recession dealt Coventry a particularly severe blow: By 1981, Coventry was in an economic crisis, with one in six of its residents unemployed. By 1982, the number of British Leyland employees in the city had fallen from 27,000 at its height, to just 8,000. Other Coventry industrial giants such as the tool manufacturer Alfred Herbert also collapsed during this time.[73]

In the late-1970s and early-1980s, Coventry also became the centre of the Two-tone musical phenomena. The two-tone style was multi-racial, derived from the traditional Jamaican music genres of ska, reggae and rocksteady combined with elements of punk rock and new wave. Bands considered part of the genre include the Specials, the Selecter, Madness, the Beat, Bad Manners, the Bodysnatchers and Akrylykz. Most famously the Specials 1981 UK no.1 hit 'Ghost Town' reflected the unemployment and desolation of Coventry at the time.[75][76]

21st century

[edit]Some motor manufacturing continued into the early 21st century: One of the research and design centres of Jaguar Land Rover is in the city at their Whitley plant and although vehicle assembly ceased at the Browns Lane plant in 2004, the head office of the Jaguar brand returned to the city in 2011, and is also sited in Whitley. The closure of the Peugeot factory at Ryton-on-Dunsmore in 2006, ended volume car manufacture in Coventry.[73] By 2008, only one motor manufacturing plant was operational, that of LTI Ltd, producing the popular TX4 taxi cabs. On 17 March 2010 LTI announced they would no longer be producing bodies and chassis in Coventry, instead producing them in China and shipping them in for final assembly in Coventry.[77]

Since the 1980s, Coventry has recovered, with its economy diversifying into services, with engineering ceasing to be a mass employer, what remains of manufacturing in the city is driven by smaller more specialist firms. By the 2010s the biggest drivers of Coventry's economy had become its two large universities; the University of Warwick and Coventry University, which between them, had 60,000 students, and a combined annual budget of around £1 billion.[73]

In 2021 Coventry became the UK City of Culture. A range of artistic and local history events and projects took place over the next year, including "Coventrypedia" and the creation of the Coventry Atlas local history map.

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]As with the rest of the British Isles and the Midlands, Coventry experiences a maritime climate with cool summers and mild winters. The nearest Met Office weather station is Coundon/Coventry Bablake. Temperature extremes recorded in Coventry range from −18.2 °C (−0.8 °F) in February 1947, to 38.9 °C (102.0 °F) in July 2022.[78] The lowest temperature reading of recent years was −10.8 °C (12.6 °F) during December 2010.[79][80]

| Climate data for Coventry (Coundon),[a] elevation: 122 m (400 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.4 (90.3) |

38.9 (102.0) |

35.1 (95.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

38.9 (102.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.7 (1.9) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61.4 (2.42) |

46.8 (1.84) |

45.6 (1.80) |

49.1 (1.93) |

52.7 (2.07) |

65.8 (2.59) |

61.2 (2.41) |

66.2 (2.61) |

54.9 (2.16) |

68.7 (2.70) |

64.6 (2.54) |

61.3 (2.41) |

698.3 (27.49) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.0 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 123.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61.4 | 84.0 | 115.1 | 147.1 | 191.6 | 184.7 | 197.6 | 179.6 | 137.1 | 100.6 | 63.1 | 61.0 | 1,507.2 |

| Source 1: Met Office[81] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BWS[82][83] RMetS[84] | |||||||||||||

- ^ Weather station is located 0.5 miles (0.8 km) from the Coventry city centre.

| Climate data for Coventry Airport, 6km from Coventry | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 83 | 79 | 75 | 74 | 73 | 72 | 74 | 78 | 83 | 87 | 88 | 79 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

3 (37) |

5 (41) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

8 (46) |

5 (41) |

3 (37) |

7 (44) |

| Source: Time and Date (between 1985–2015)[85] | |||||||||||||

City boundaries

[edit]Coventry forms the largest part of the Coventry and Bedworth Urban Area. The city proper covers an area of almost 100 km2 (39 sq mi).

The protected West Midlands Green Belt, which surrounds the city on all sides, has prevented the expansion of the city into both the administrative county of Warwickshire and the metropolitan borough of Solihull (the Meriden Gap), and has helped to prevent the coalescence of the city with surrounding towns such as Kenilworth, Nuneaton, Leamington Spa, Warwick and Rugby as well as the large village of Balsall Common.

Panoramic views of Coventry City Centre from the cathedral tower

Suburbs and other surrounding areas

[edit]- Alderman's Green

- Allesley

- Allesley Green

- Allesley Park

- Ash Green

- Ball Hill

- Bannerbrook Park

- Bell Green

- Binley

- Bishopsgate Green

- Brownshill Green

- Canley & Canley Gardens

- Cannon Park

- Chapelfields

- Cheylesmore

- Church End

- Clifford Park

- Copsewood

- Coundon

- Courthouse Green

- Daimler Green

- Earlsdon

- Eastern Green

- Edgwick (or Edgewick)

- Ernesford (or Ernsford) Grange

- Finham

- Fenside

- Foleshill

- Gibbet Hill

- Gosford Green

- Great Heath

- Hearsall Common

- Henley Green

- Hillfields

- Holbrooks

- Keresley

- Little Heath

- Longford

- Middle Stoke

- Monks Park

- Mount Nod

- Nailcote Grange

- Pinley

- Potters Green

- Radford

- Spon End

- Stoke

- Stoke Heath

- Stoke Aldermoor

- Stivichall (or Styvechale)

- Tanyard Farm

- Tile Hill

- Toll Bar End

- Upper Stoke

- Victoria Farm

- Walsgrave-on-Sowe

- Westwood Heath

- Whitley

- Whitmore Park

- Whoberley

- Willenhall

- Wood End

- Woodway Park

- Wyken

Compass

[edit]Places of interest

[edit]Cathedral

[edit]The spire of the ruined cathedral forms one of the "three spires" which have dominated the city skyline since the 14th century, the others being those of Christ Church (of which only the spire survives) and Holy Trinity Church (which is still in use).

St Michael's Cathedral is Coventry's best-known landmark and visitor attraction. The 14th century church was largely destroyed by German bombing during the Second World War, leaving only the outer walls and spire. At 300 feet (91 metres) high, the spire of St Michael's is claimed to be the third tallest cathedral spire in England, after Salisbury and Norwich.[86] Due to the architectural design (in 1940 the tower had no internal wooden floors and a stone vault below the belfry) it survived the destruction of the rest of the cathedral.

The new Coventry Cathedral was opened in 1962 next to the ruins of the old. It was designed by Sir Basil Spence. The cathedral contains the tapestry Christ in Glory in the Tetramorph by Graham Sutherland. The bronze statue St Michael's Victory over the Devil by Jacob Epstein is mounted on the exterior of the new cathedral near the entrance. Benjamin Britten's War Requiem, regarded by some as his masterpiece, was written for the opening of the new cathedral.[87] The cathedral was featured in the 2009 film Nativity!.[88]

Coventry Cathedral is also notable for being one of the newest cathedrals in the world, having been built following the Second World War bombing of the ancient cathedral by the Luftwaffe. Coventry has since developed an international reputation as one of Europe's major cities of peace and reconciliation,[89] centred on its cathedral, and holds an annual Peace Month.[90] John Lennon and Yoko Ono planted two acorns outside the cathedral in June 1968 to thank the city for making friends with others.[91]

Coventry also has a Baptist church named Queens Road Baptist Church, which was first established in 1723 and moved to its current building in 1884.

Cultural institutions

[edit]

The Herbert Art Gallery and Museum is one of the largest cultural institutions in Coventry. Another visitor attraction in the city centre is Coventry Transport Museum, which has the largest public collection of British-made road vehicles in the world.[92] The most notable exhibits are the world speed record-breaking cars, Thrust2 and ThrustSSC[93] The museum received a refurbishment in 2004 which included the creation of a new entrance as part of the city's Phoenix Initiative project. It was a finalist for the 2005 Gulbenkian Prize.

Historic Coventry Trust (previously known as The Charterhouse Coventry Preservation Trust) was founded in 2011. The Trust is a social enterprise aiming to regenerate Coventry's historic buildings and landscapes. Their sites across Coventry include the Charterhouse, the two surviving City Gates, Drapers' Hall, London Road Cemetery: Paxton's Arboretum and Priory Row.[94]

The £5 million Fargo Village creative quarter shopping precinct was open in 2014 on Far Gosford Street with a mixture of retail units.

About four miles (6.4 kilometres) from the city centre and just outside Coventry in Baginton is the Lunt Fort, a reconstructed Roman fort on its original site. The Midland Air Museum is situated just within the perimeter of Coventry on land adjacent to Coventry Airport and near Baginton.

Coventry was one of the main centres of watchmaking during the 18th and 19th centuries and as the industry declined, the skilled workers were key to setting up the cycle trade. A group of local enthusiasts founded the Coventry Watch Museum in Spon Street.[48]

The city's main police station in Little Park Street also hosts a museum of Coventry's police force. The museum, based underground, is split into two sections—one representing the history of the city's police force, and the other compiling some of the more unusual, interesting and grisly cases from the force's history. The museum is funded from charity donations—viewings can be made by appointment.

Coventry City Farm was a small farm in an urban setting. It was mainly to educate city children who might not get out to the countryside very often. The farm closed in 2008 due to funding problems.[95]

Demographics

[edit]

| Coventry ethnicity demographics from the 2021 census[1] | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Population |

| White (British, Irish, Other) |

226,246 |

| Asian (Indian, Bangladeshi, Chinese, Pakistani, Other) |

63,915 |

| Black (African, Caribbean, Other) |

30,723 |

| Mixed (White & Asian, White & Black African, White & Black Caribbean, Other) |

11,731 |

| Other | 12,706 |

Coventry has an ethnic minority population which represented 34.5% of the population at the 2021 census.[1] The ethnic minority population is concentrated in the Foleshill and the St Michael's wards.[96] Islam is the largest non-Christian religion, but the composition of the ethnic minority population is not typical of the UK with significant numbers of other South Asians. Both Sikh and Hindu religions are represented significantly higher than in the rest of the West Midlands in general.[97]

Coventry has a large student population (approximately 15,000 are non-UK[98]) who are in the UK for 12 months or longer that are included in these figures.

| Year | Total population[99] |

|---|---|

| 1801 | 21,853 |

| 1851 | 48,120 |

| 1901 | 88,107 |

| 1911 | 117,958 |

| 1921 | 144,197 |

| 1931 | 176,303 |

| 1941 | 214,380 |

| 1951 | 260,685 |

| 1961 | 296,016 |

| 1971 | 336,136 |

| 1981 | 310,223 |

| 1991 | 305,342 |

| 2001 | 300,844 |

| 2007 | 306,700 |

| 2009 | 309,800 |

| 2010 | 310,500 |

| 2011 | 316,960[100] |

| 2013 | 329,810[101] |

| 2014 | 337,428[102] |

| 2015 | 345,385[103] |

| 2016 | 352,911[104] |

| 2017 | 360,100[105] |

| 2018 | 366,785[106] |

| 2021 | 345,328[107] |

| Coventry religious demographics from the 2021 census[1] | |

|---|---|

| Religion | Population |

| Christian | 151,577 |

| No Religion | 102,338 |

| Muslim | 35,800 |

| Undeclared | 21,166 |

| Sikh | 17,297 |

| Hindu | 13,724 |

| Buddhist | 1,257 |

| Jewish | 259 |

| Other | 1,908 |

According to the 2021 Census, 43.9% (151,577) of residents identified themselves as Christian making Christianity the largest followed religion in the city. Islam was the second most followed religion with 10.4% (35,800) of residents identifying with the religion. 5.0% (17,297) of Coventry's population were Sikh, disproportionately larger than the national average in England of 0.8%. Hindus made up 4.0% (13,724) of the resident population followed by Buddhists at 0.4% (1,257) and Jews at 0.1% (259) respectively. The adherents of other religions made up 0.6% (1,908) of the city's population.

Almost a third of Coventry residents, 29.6% (102,338), identified themselves as having no religion and 6.1% did not declare any religion.[1]

Government and politics

[edit]Local and national government

[edit]

Traditionally a part of Warwickshire (although it was a county in its own right for 400 years), Coventry became an independent county borough in 1889. It later became a metropolitan district of the West Midlands county under the Local Government Act 1974 (c. 7), even though it was entirely separate to the Birmingham conurbation area (this is why Coventry appears to unnaturally "jut out" into Warwickshire on political maps of the UK). In 1986, the West Midlands County Council was abolished and Coventry became administered as an effective unitary authority in its own right.

Coventry is administered by Coventry City Council, controlled since 2010 by the Labour Party, and led since May 2016 by George Duggins.[108] The city is divided up into 18 Wards each with three councillors. The chairman of the council is the Lord Mayor, who has a casting vote.

Certain local services are provided by West Midlands wide agencies including the West Midlands Police, the West Midlands Fire Service and Transport for West Midlands (Centro) which is responsible for public transport.

In 2006, Coventry and Warwickshire Ambulance Service was merged with the West Midlands Ambulance Service. The Warwickshire and Northamptonshire Air Ambulance service is based at Coventry Airport in Baginton.

Coventry is represented in Parliament by three Members of Parliament (MPs). They are:

- Mary Creagh – (Coventry East)

- Zarah Sultana – (Coventry South)

- Taiwo Owatemi – (Coventry North West)

Up until 1997, Coventry was represented by four Members of Parliament, whereupon the Coventry South West and Coventry South East constituencies were merged to form Coventry South.

On Tuesday, 10 September 2024, Zarah Sultana, the Member of Parliament for Coventry South, was suspended from the Labour Party for voting in favour of a Scottish National Party amendment to end the two child benefit cap.[109]

On Thursday, 19 May 2016, Councillor Lindsley Harvard was inaugurated Lord Mayor of Coventry for 2016–17 as Coventry's 65th Lord Mayor. Councillor Lindsley Harvard has been a Labour Councillor serving on the council for fourteen years, for Earlsdon Ward (1996–2000) and for Longford Ward since 2006.[110] On Thursday, 19 May 2016, Councillor Tony Skipper was inaugurated as the Deputy Lord Mayor of Coventry for 2016–17. He has been a Labour councillor since 1995; representing Earlsdon Ward between 1995 and 2001, and then Radford Ward since 2001.[111]

The Bishop of Coventry is Christopher John Cocksworth, who was consecrated on 3 July 2008.[112]

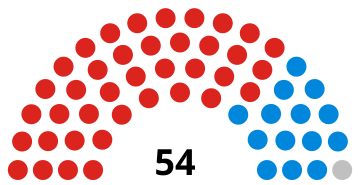

Council affiliation

[edit]In May 2016, it was as follows[113]

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Party | Councillors | |

| Labour Party | 39 | |

| Conservative Party | 14 | |

| Independent | 1 | |

| Total | 54 | |

Twinning with other cities; "city of peace and reconciliation"

[edit]Coventry and Stalingrad (now Volgograd) were the world's first 'twin' cities when they established a twinning relationship during the Second World War.[114][115] The relationship developed through ordinary people in Coventry who wanted to show their support for the Soviet Red Army during the Battle of Stalingrad.[116] The city was also subsequently twinned with Dresden, as a gesture of peace and reconciliation following the Second World War. Each twin city country is represented in a specific ward of the city and in each ward has a peace garden dedicated to that twin city.[citation needed] Coventry is now twinned with 26 places across the world:[117][118] On 22 March 2022, Coventry City Council voted unanimously to suspend the twinning arrangement with Volgograd in light of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[119]

| City | Country | Year twinned | Ward |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graz[117][118][120] | Austria | 1957 | Binley & Willenhall |

| Sarajevo[117][118] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1957 | Cheylesmore |

| Cornwall, Ontario[117][118] | Canada | 1972 | Earlsdon |

| Granby, Quebec[117][118] | 1963 | ||

| Windsor, Ontario[117][118] | 1963 | ||

| Jinan[117][118] | China | 1983 | Foleshill |

| Lidice[117][118] | Czech Republic | 1947 | Henley |

| Ostrava[117][118] | 1959 | ||

| Caen[117][118][121] | France | 1957 | Longford |

| Saint-Étienne[117][118][121] | 1955 | ||

| Dresden[117][118] | Germany | 1959 | Lower Stoke |

| Kiel[117][118] | 1947 | ||

| Dunaújváros[117][118] | Hungary | 1962 | Radford |

| Kecskemét[117][118] | 1962 | ||

| Bologna[117][118] | Italy | 1960 | Sherbourne |

| Kingston[117][118] | Jamaica | 1962 | St Michael's |

| Arnhem[117][118] | Netherlands | 1958 | Upper Stoke |

| Warsaw[117][118] | Poland | 1957 | Wainbody |

| Cork[117][118][122] | Ireland} | 1958 | Holbrooks |

| Galați[117][118] | Romania | 1962 | Westwood |

| Volgograd/Stalingrad[117][118] (suspended)[119] | Russia | 1944 | Whoberley |

| Belgrade[117][118] | Serbia | 1957 | Woodlands |

| Coventry, Connecticut[117][118] | United States | 1962 | Wyken |

| Coventry, New York[117][118] | 1972 | ||

| Coventry, Rhode Island[117][118] | 1971 |

Arts and culture

[edit]On 7 December 2017 it was announced that the city would be the 2021 UK City of Culture, being the third such place to hold the title after Derry in 2013 and Hull in 2017.[123] After the financial collapse of the Coventry City of Culture Trust,[124][125] set up to run legacy projects following Coventry's year as UK City of Culture in 2021, local MP Taiwo Owatemi raised an adjournment debate in the House of Commons.[126]

Literature and drama

[edit]- The African American actor Ira Aldridge managed Coventry Theatre after impressing the people of the city with his acting during a tour in 1828. He was born in New York in 1807, but moved to England when he was18, and is considered the UK's first black Shakespearean performer.[127]

- The poet Philip Larkin was born and brought up in Coventry,[128] where his father was the City Treasurer.

- During the early 19th century, Coventry was well known due to author George Eliot who was born near Nuneaton, Warwickshire. The city was the model for her famous novel Middlemarch (1871).

- The Coventry Carol is named after the city of Coventry. It was a carol performed in the play The Pageant of the Shearman and Tailors, written in the 15th century as one of the Coventry Cycle Mystery Plays. These plays depicted the nativity story, the lyrics of the Coventry Carol referring to the Annunciation to the Massacre of the Innocents, which was the basis of the Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors. These plays were traditionally performed on the steps of the (old) cathedral. The Belgrade Theatre brought back the Coventry Mystery Plays in 2000 to mark the city's millennium celebrations: the theatre now produces the Mystery Plays every three years.

- The Belgrade Theatre was Britain's first purpose-built civic theatre, opened in 1958. In 1965 the world's first Theatre-in-Education (TiE) company was formed to develop theatre as a way of inspiring learning in schools. The TiE movement spread worldwide, the theatre still offers a number of programmes for young people across Coventry and has been widely recognised as a leader in the field. It was reopened in 2007 following a period of refurbishment.[129]

- Novelist Graham Joyce, winner of the O. Henry Award is from Keresley. His World Fantasy Award-winning novel "The Facts of Life" is set in Coventry during the blitz and in the post-war rebuilding period.

- The playwright Alan Pollock[130] was brought up in Coventry. Other playwrights associated with the city include Nick Walker and Chris O'Connell – founder of the city's Theatre Absolute.

- Brian Saunders lived in Coventry and was featured, along with his partner Andrew Stuart Sutton and Pete and Les Cardy, in the series A Place In Greece in 2004 and 2005.

Music and cinema

[edit]During the late-1970s and early 1980s, Coventry was the centre of the Two Tone musical phenomenon, with bands such as The Specials and The Selecter coming from the city.[131] The Specials achieved two UK number 1 hit singles between 1979 and 1981, namely "Too Much Too Young" and "Ghost Town".

Coventry has a range of music events including an international jazz programme, the Coventry Jazz Festival, and the Godiva Festival. On the Saturday of the Godiva Festival, a carnival parade starts in the city centre and makes its way to War Memorial Park where the festival is held. Coventry's music is celebrated at The Coventry Music Museum, part of the 2-Tone Village complex.

In the 1969 film The Italian Job, the famous scene of Mini Coopers being driven at speed through Turin's sewers was actually filmed in Coventry, using what were then the country's biggest sewer pipes, that were accessible because they were being installed. The BBC medical TV drama series Angels, which ran from 1975 to 1983 was filmed at Walsgrave Hospital.[132]

More recently various locations in Coventry have been used in the BAFTA nominated film The Bouncer starring Ray Winstone, All in the Game, also starring Ray Winstone (Ricoh Arena), the BBC sitcom Keeping Up Appearances (Stoke Aldermoor and Binley Woods districts). In August 2006 scenes from "The Shakespeare Code", an episode of the third series of Doctor Who, were filmed in the grounds of Ford's Hospital. The 2013 ITV comedy-drama Love and Marriage was also set in the city. Coventry is home to three major feature films the Nativity! franchise which are all shot and set in the city.[133] These Christmas films have all reached top box office spots on their release in UK cinemas. Their writer and director the Bafta award-winning Debbie Isitt is resident in the city. In 2023, the 10 part TV series Phoenix Rise was set and filmed in Coventry.[134]

BBC Radio 1 has announced that its BBC Radio One's Big Weekend will take place in Coventry at the end of May 2022, as part of the closing ceremony for the UK City of Culture.[135]

Customs and traditions

[edit]Coventry Godcakes are a regional delicacy, originating from the 14th century and are still baked today.[136][137]

The Coventry Flag

[edit]

The Coventry Flag,[138] designed by Simon Wyatt,[139] was adopted through a popular vote on 7 December 2018. The Coventry Flag represents the unique identity of the Warwickshire city and its residents. It emerged as the winner in a competition organised by BBC Coventry & Warwickshire[139] and proudly flew during Coventry's tenure as the UK City of Culture in 2021. The design features Lady Godiva, a local heroine, depicted in black on a white pale, symbolising Coventry's history, principles, and its reputation as a city of peace. Sky blue panels on either side of Lady Godiva represent "Coventry Blue," reminiscent of the historic local textile industry and Coventry City Football Club, known as the "Sky Blues."

Venues and shopping

[edit]

There are several theatre, art and music venues in Coventry attracting popular sporting events and singing musicians. Along with this, the city has several retail parks located out of the city centre and its own shopping mall in the heart of the city:

- Warwick Arts Centre: situated at the University of Warwick, Warwick Arts Centre includes an art gallery, a theatre, a concert hall and a cinema.

- FarGo Village, a creative quarter with various independent businesses.

- Albany Theatre: is the city's main community theatre. It is housed at what used to be the Butts Centre of City College Coventry. Known as the Butts or College Theatre, it closed in 2009 with the sale of the college to private developers. The theatre re-opened in 2013 as the Albany Theatre, as part of the Premier Inn hotel on the site of the former Butts Technical College and is run as a charitable trust with support from the council.

- Belgrade Theatre: one of the largest producing theatres in Britain, the 858-seat Belgrade was the first civic theatre to be opened in the UK following the Second World War. The theatre underwent a huge redevelopment and reopened in September 2007; in addition to refurbishing the existing theatre, the redevelopment included a new 250-seat studio auditorium known as B2, a variety of rehearsal spaces and an exhibition space that traces the history of theatre in Coventry. It is surrounded by Belgrade Plaza.

Coventry Building Society Arena: located 4 miles (6.4 kilometres) north of the city centre, the 32,600 capacity sports stadium which is home to the city's only professional football team Coventry City, who play in the second tier of English football, and is also used to hold major concerts for some of the world's biggest acts, including Oasis, Bon Jovi, Coldplay, Lady Gaga, Rod Stewart, Kings of Leon and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. It was also one of the venues chosen for the footballing events at the 2012 Olympic Games. The adjacent Jaguar Exhibition Hall is a 6,000-seat events venue for hosting a multitude of other acts.

- SkyDome Arena, which is a 3,000 capacity sports auditorium, and has played host to artists such as Girls Aloud, Paul Oakenfold and Judge Jules. It is the home ground for Coventry Blaze ice hockey club, and has also hosted professional wrestling events from WWE, TNA and Pro Wrestling Noah.

- War Memorial Park—known by locals simply as the Memorial Park—which holds various festivals including the Godiva Festival and the Coventry Caribbean Festival, every year. It also host the weekly Parkrun event.

- Butts Park Arena, home of Coventry Rugby Football Club and Coventry Bears Rugby League Club, holds music concerts occasionally.

- Criterion Theatre, a small theatre, in Earlsdon.

- Coombe Country Park, although outside the city boundary, Coventry City Council's only country park. It surrounds the former Coombe Abbey which now operates as a hotel.

- The Wave – an indoor water park and spa, owned and operated by Coventry City Council, was opened in 2019.

- Herbert Art Gallery and Museum – a museum, art gallery, records archive, learning centre, media studio and creative arts facility on Jordan Well, Coventry.

- Coventry Transport Museum – one of the largest motor museums in the UK.

Sport

[edit]

On the sporting scene, Coventry Rugby Football Club was consistently among the nation's leading rugby football sides from the early 20th century, peaking in the 1970s and 1980s. Association football, on the other hand, was scarcely a claim to fame until 1967, when Coventry City F.C. finally won promotion to the top flight of English football as champions of the Football League Second Division.[140] They would stay among the elite for the next 34 years, reaching their pinnacle with FA Cup glory in 1987—the first and to date only major trophy in the club's history.[141] Their long stay in the top flight of English football ended in relegation in 2001,[142] and in 2012 they were relegated again to the third tier of English football. Highfield Road, to the east of the city centre, was Coventry City's home for 106 years from 1899. They finally departed from the stadium in 2005 on their relocation to the 32,600-seat Ricoh Arena some three miles (4.8 kilometres) to the north of the city centre, in the Rowleys Green district.[143] Since 2000, the city has also been home to one of the most successful ice hockey teams in the country, the Coventry Blaze who are four time Elite League champions, and play their home games at the SkyDome Arena.

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coventry City F.C. | Football | 1883 | EFL Championship | Coventry Building Society Arena |

| Coventry Sphinx L.F.C. | Football | 2012 | West Midlands Regional Women's Football League | Coventry Sphinx Sports and Social Club |

| Coventry United L.F.C | Football | 2015 | FA Women's Championship | Butts Park Arena |

| Coventry R.F.C. | Rugby union | 1874 | RFU Championship | Butts Park Arena |

| Coventry Bees | Speedway | 1928 | ||

| Coventry Blaze | Ice hockey | 2000 | Elite Ice Hockey League | SkyDome Arena |

| Broadstreet RFC | Rugby Union | 1929 | National League 2 (North) | Ivor Preece Field |

| Coventry Jets | American football | 2003 | BAFA National Leagues | Coventry Sphinx Sports and Social Club |

| Coventry Sphinx F.C. | Football | 1946 | Midland Football League Premier Division | Coventry Sphinx Sports and Social Club |

| Coventry United F.C. | Football | 2013 | Midland Football League Premier Division | Butts Park Arena |

Football

[edit]

There are two professional football teams representing the city: Coventry City F.C. of the EFL Championship in men's football and Coventry United L.F.C. of the FA Women's Championship in women's football.

Coventry City F.C., formed in 1883 as "Singers F.C.". Nicknamed the Sky Blues, the club competes in the EFL Championship (second tier of English football), but spent 34 years from 1967 to 2001 in the top tier of English football, winning the FA Cup in 1987. They were founder members of the Premier League in 1992. In 2005, Coventry City moved to the 32,600 capacity Ricoh Arena which opened in the Rowleys Green district of the city. The 2013–14 season saw the football club begin a ground share with Northampton Town F.C. at Sixfields Stadium, Northampton, which lasted until their return to the Ricoh Arena in September 2014. The 2019–20 season saw the Sky Blues once again playing their home fixtures out of Coventry, at Birmingham City's St Andrew's Stadium. This arrangement continued until August 2021, when Coventry moved back to the newly renamed Coventry Building Society Arena.

Coventry United L.F.C. play at the Butts Park Arena and were originally Coventry City Ladies before the Sky Blues discontinued their women's team, at which point they affiliated with Coventry United, and rose through the divisions to their current position in the second-tier of the women's game.

Aside from these clubs, there are several other clubs in the city playing non-league football. Coventry Sphinx, Coventry Alvis, Coventry Copsewood and Coventry United all play in the Midland Football League.

Both Coventry University and the University of Warwick compete in the British Universities and Colleges Sport (BUCS) football competitions. For the 2014–15 season, the Coventry University men's 1st team compete in BUCS Midlands 1a, while the University of Warwick men's 1st team competes in BUCS Midlands 2a. Both institutions' women's 1st teams both play in BUCS Midlands 2a.

Rugby Union

[edit]At the beginning of the 2014–15 season, there were 14 clubs based in Coventry, playing at various levels of the English rugby union system. However, on 21 December 2014, this rose to 15, when Aviva Premiership club Wasps RFC played their first home game at the Ricoh Arena, completing their relocation to the city. This followed Wasps' purchase of Arena Coventry Limited (the company which runs the Ricoh Arena). The club announced that they will build a new 'state of the art' training complex in the area by 2016.[144]

Wasps' stay in the City ended in 2022 after the club collapsed into administration and were forced to relinquish their ownership of the arena.[145] As it stands, Wasps currently have no plans to play in Coventry again.

Coventry Rugby Football Club play in the RFU Championship, the second tier of the English rugby union system. The club enjoyed national success during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, with many of its players playing for their countries, notable players include Ivor Preece, Peter Jackson, David Duckham, Fran Cotton and Danny Grewcock. From 1921 to 2004, the club played at Coundon Road Stadium. Their current home ground is the Butts Park Arena, which was opened in 2004.

Broadstreet R.F.C. are the only other club to play in a 'national league' currently playing in National Division 2 North.

There are a further 12 clubs playing in the Midland divisions of the English Rugby Union system. In 2015, they included Barkers Butts RFC, Dunlop RFC, Earlsdon RFC, Pinley, Old Coventrians, Coventrians, Coventry Welsh, Stoke Old Boys RFC, Copsewood RFC, Keresley RFC, Old Wheatleyans RFC and Trinity Guild RFC.

Both Coventry University and the University of Warwick compete in the British Universities and Colleges Sport (BUCS) Rugby competitions.

Rugby League

[edit]Midlands Hurricanes are the major rugby league team in the city. Originally known as Coventry Bears, the Hurricanes compete in the Betfred League 1, as a semi-professional team in the third tier of the game. They play their home matches at the Butts Park Arena.

In 2002, the club won the Rugby League Conference, and took the step up to the national leagues. In 2004, they won the National Division 3 title and have appeared in the Challenge Cup. In 2015 the Bears entered their reserve team into the Conference League South league, a level below the first team under the name Coventry Bears Reserves playing home games at the Xcel Leisure Centre.

Both Coventry University and the University of Warwick compete in the British Universities and Colleges Sport (BUCS) Midlands 1a competition.

Speedway

[edit]Coventry Speedway was based at Brandon Stadium (also known as Coventry Stadium). The stadium is located just outside the city in the village of Brandon, Warwickshire (6 miles (9.7 kilometres) to the east of the city). The stadium operated both sides of the Second World War. Before the Second World War speedway also operated for a short time at Foleshill Stadium, off Lythalls Lane in the city. Between 1998 and 2000, Coventry Stadium hosted the Speedway Grand Prix of Great Britain.

The Coventry Bees started in 1948 and operated continuously until the end of the 2018 season. They started out in the National League Division Three before moving up to the Second Division and, later to the top flight. The Bees were crowned League Champions on nine occasions (1953, 1968, 1978, 1979, 1987, 1988, 2005, 2007 and 2010).

Amongst the top speedway riders who represented Coventry teams were Tom Farndon, Jack Parker, Arthur Forrest, Nigel Boocock, Kelvin Tatum, Chris Harris, Scott Nicholls, Emil Sayfutdinov and World Champions Ole Olsen, Hans Nielsen, Greg Hancock, Billy Hamill, Ronnie Moore and Jack Young.

In 2007, the Bees won the domestic speedway treble of Elite League, Knock-out Cup and Craven Shield, while Chris Harris won both the Speedway Grand Prix of Great Britain and the British Championship. The Bees retained the Craven Shield in 2008, and Chris Harris added further British Championship victories in both 2009 and 2010. The Elite League Championship Trophy returned to Brandon in 2010 when the Bees convincingly beat Poole Pirates in the play-off finals.[146]

The Coventry Storm, an offshoot of the senior team, competed in the National League.

In 2017, the stadium became unavailable for motorsports, with new owners Brandon Estates pursuing planning permission for housing – thus, neither Coventry team was able to compete in the leagues, although a number of challenge matches were undertaken on opposition teams' tracks.

For 2018, Coventry Bees were entered into the National League, the third tier of British Speedway, riding their home meetings at the home of Leicester Lions. The team has not operated since then.

Ice hockey

[edit]

The Coventry Blaze are one of the founding teams of the Elite Ice Hockey League. They competed in the Erhardt Conference from 2012–13 to 2017–18 before moving to the Patton Conference playing in that conference until the conference system was removed at the end of the 2018–19 season.They play their matches at the SkyDome Arena. In 2002–2003, they won the British National League and Playoffs. They have won the Elite League Championship four times (2005, 2007, 2008 and 2010). The team has twice won the British Challenge Cup, in 2005 & 2007. The 2004–05 EIHL season saw the club win the Grand slam (namely the Championship, the Challenge Cup and the Playoffs). To date, they remain the only team since the formation of the Elite League to achieve this feat. Coventry Blaze celebrated their 10th anniversary season in 2009–10 by winning the Elite League.[147] The club also run a successful academy system, developing the young players of Coventry, Warwickshire and beyond. Scorch the dragon is the official Blaze mascot. The NIHL Coventry Blaze, an offshoot of the senior team and official affiliate of the Blaze, currently compete in the National Ice Hockey League.

The Coventry Phoenix is the city's only women's team; currently competing in Division One (North) of the British Women's Leagues. There are also several recreational ice hockey teams (male and female) that play in the city.

The Coventry and Warwick Panthers are members of the British Universities Ice Hockey Association. The 'A' team compete in "Checking 1 South", 'B' in "Non-Checking 1 South" and 'C' in "Non-Checking 2 South".

Stock car racing

[edit]Coventry Stadium held BriSCA Formula 1 Stock Cars from 1954 until 2016, the longest serving track in the UK to race continuously.[148] The first meeting was held on 30 June 1954, the first heat being won by Percy 'Hellcat' Brine, he also won the meeting Final. Up to the end of 2013, the stadium had held 483 BriSCA F1 meetings.[149] It held the BriSCA Formula 1 Stock Cars World Championship many times since 1960. As with speedway, Stock Car racing ceased in 2017 because of the unavailability of the stadium.

Cricket

[edit]The city's current leading cricket club is Coventry and North Warwickshire Cricket Club. Coventry & North Warwickshire CC is currently competing in the ECB Birmingham & District Premier Cricket League, having won the Warwickshire Premier Division in 2022, achieving promotion through the county league play-offs against the respective winners of the Worcestershire, Staffordshire and Shropshire premier leagues.

Historically, first class county games were played by Warwickshire County Cricket Club at the Courtaulds Ground from 1949 up to 1982. After Courtaulds Ground was closed, Warwickshire played several games at Coventry and North Warwickshire Cricket Club at Binley Road.

Coventry born Yvonne Dolphin-Cooper is a cricket umpire. She, alongside Anna Harris, made history in 2021 by becoming the first-all female umpiring duo ever in ECB Premier League history when they officiated together in a West of England Premier League match between Downend CC and Bedminster in Gloucestershire.[150]

Athletics

[edit]The Coventry Godiva Harriers, established in 1879, are the leading athletics club in the area. The club has numerous athletes competing for championships both nationally and internationally. Notable members[151] (past and present) include:

- Basil Heatley; former world record holder for the marathon and silver medalist in the 1964 Summer Olympics.

- David Moorcroft; Gold medalist in the 1500m at the 1978 Commonwealth Games and in the 5000m at the 1982 Commonwealth Games. He is the former World 5000m record holder and still holds the British 3000m record.

- Marlon Devonish; individually in his senior career, he won Gold for the 200m at the 2003 World Indoor Championship and silver at the 2002 Commonwealth Games. However, he has had great success as a relay runner in the 4 × 100 m, winning gold medals at the 2004 Summer Olympics, 1998 Commonwealth Games, 2002 Commonwealth Games and the 2010 Commonwealth Games. He also won bronze at World and European level at both his distances.

Field hockey

[edit]A field hockey club in the city is Coventry & North Warwickshire Hockey Club, which was established in 1895. Based at the Coventry University Sports Ground, the club runs four men's and two ladies' sides, as well as a junior section.

The men's first XI currently compete in Midlands Division 1 of the Midland Regional Hockey Association (MHRA), while the ladies' first XI compete in Warwickshire Women's Hockey League Division 1.

Other teams in the city include:

- Sikh Union: Men's 1st XI – (MHRA West Midlands Premier)

- Berkswell & Balsall Common Men's 1st XI – (MHRA East Midlands 1); Women's 1st XI – (Warwickshire Women's Hockey League Division 2)

The University of Warwick field men's teams both in the MHRA and the British Universities and Colleges Sport (BUCS) hockey competitions. They compete in MHRA Midlands 2 and in BUCS Midlands 2b. The women's first XI compete in BUCS Midlands 3a. Coventry University men's first XI play in BUCS Midlands 3b, while the women's first XI compete in BUCS Midlands 2a.

Golf

[edit]Dame Laura Davies DBE was born in Coventry and is among the most successful female golfers from Britain. She has had 87 tournament victories, including major wins at the Belgium Open in 1985, the Ladies British Open in 1986, and the US Women's Open in 1987.[152] From the early 90s she played in 12 consecutive Solheim Cups in the US.[152] Laura has won numerous accolades during her career and was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2015.[153]

In 1961, Ralph Moffitt, assistant professional at Coventry Hearsall G.C., was selected and played for Great Britain in the Ryder Cup against the U.S.A. at Royal Lytham St. Anne’s G.C.

Other

[edit]In 2005, Coventry became the first city in the UK to host the International Children's Games and three of the city sports teams won significant honours.[154] The Blaze won the treble consisting of Elite League, playoff and Challenge Cup; the Jets won the BAFL Division 2 championship and were undefeated all season; and the Bees won the Elite League playoffs.

In 2014 the all-female Coventry City Derby Dolls was founded, now called Coventry Roller Derby (CRD).[155] They were the first roller derby team in Coventry and Warwickshire,[156] train weekly and have a full bout team[157]

Economy

[edit]

Historically, Coventry was the most important seat of ribbon-making in the UK. In this industry it competed locally with Norwich and Leicester and internationally with Saint-Étienne in France.

Coventry has been a centre of motor and cycle manufacturing. Starting with Coventry Motette, The Great Horseless Carriage Company, Swift Motor Company, Humber, Hillman, Riley, Francis-Barnett and Daimler and Triumph motorcycles having its origins in 1902 in a Coventry factory. The Massey Ferguson tractor factory was situated on Banner Lane, Tile Hill, until it closed in the early 2000s.

Although the motor industry has declined almost to the point of extinction, Jaguar Land Rover has retained its Jaguar brand headquarters in the city (at Whitley) and an Advanced R&D team at the University of Warwick, while Peugeot still have a large parts centre in Humber Road despite the closure of its Ryton factory (formerly owned by the Rootes Group) just outside the city in December 2006 with the loss of more than 2,000 jobs – denting the economy of Coventry shortly before the onset of a recession which sparked further economic decline and high unemployment.

The Standard Motor Company opened a car factory at Canley in the south of the city in 1918, occupying a former munitions factory. This site was later expanded and produced Triumph cars after the Standard brand was phased out by BMC during the 1960s. In August 1980, however, it was closed down as part of British Leyland's rationalisation process, although the Triumph brand survived for another four years on cars produced at other British Leyland factories. The closure of the Triumph car factory was perhaps the largest blow to Coventry's economy during the early 1980s economic decline.

The famous London black cab taxis are produced by Coventry-based LEVC (formerly LTI); until its 2017 relocation from the historic Holyhead Road factory to a new plant at Ansty Park a few miles outside the city, these were the only remaining motor vehicles wholly built in Coventry.

The manufacture of machine tools was once a major industry in Coventry. Alfred Herbert Ltd became one of the largest machine tool companies in the world. In later years the company faced competition from foreign machine tool builders and ceased trading in 1983. Other Coventry machine tool manufacturers included A.C. Wickman, and Webster & Bennett. The last Coventry machine tool manufacturer was Matrix Churchill which was forced to close in the wake of the Iraqi Supergun (Project Babylon) scandal.

Coventry's main industries include: cars, electronic equipment, machine tools, agricultural machinery, man-made fibres, aerospace components and telecommunications equipment. In recent years, the city has moved away from manufacturing industries towards business services, finance, research, design and development and creative industries.

Redevelopment

[edit]

Major improvements continue to regenerate the city centre. The Phoenix Initiative, which was designed by MJP Architects, reached the final shortlist for the 2004 RIBA Stirling Prize and has now won a total of 16 separate awards. It was published in the book 'Phoenix : Architecture/Art/Regeneration' in 2004.[158] Further major developments are potentially afoot, particularly the Swanswell Project, which is intended to deepen Swanswell Pool and link it to Coventry Canal Basin, coupled with the creation of an urban marina and a wide Parisian-style boulevard. A possible second phase of the Phoenix Initiative is also in the offing, although both of these plans are still on the drawing-board. On 16 December 2007, IKEA's first city centre store in the UK was opened, in Coventry.[159][160]

On 4 February 2020, it was announced that IKEA's Coventry city centre store was to close the same year due to changing shopping habits and consistent losses at the store.[161]

The River Sherbourne runs under Coventry's city centre; the river was paved over during the rebuilding after the Second World War and is not commonly known. When the new rebuild of Coventry city centre takes place from 2017 onwards, it is planned that river will be re-opened, and a river walk way will be placed alongside it in parts of the city centre.[162] In April 2012, the pedestrianisation of Broadgate was completed.[163]

Media

[edit]Radio

[edit]Local radio stations include:

- BBC CWR: 94.8 FM

- Capital Mid-Counties (formerly Touch FM): 96.2 FM

- Hits Radio Coventry & Warwickshire (formally known as Mercia Sound, Mercia FM, Mercia and Free Radio Coventry & Warwickshire): 97.0 FM

- Greatest Hits Radio West Midlands: 1359 AM

- Fresh West Midlands: DAB

Written media

[edit]

The main local newspapers are:

- Coventry Telegraph: a paid for newspaper printed Monday to Saturday, owned by Reach.

- Coventry Observer

Television news

[edit]The city is covered on regional TV News by:

- BBC Midlands Today: run by the British public service broadcaster.

- ITV News Central

Digital-only media

[edit]- HelloCov: an online news website founded in 2018.[164]

- Coventry Times

Public services

[edit]Emergency services

[edit]Coventry is covered by West Midlands Police, the West Midlands Fire Service and the West Midlands Ambulance Service.

Healthcare

[edit]

Healthcare in Coventry is provided primarily by the National Health Service (NHS); the principal NHS hospital covering the city is the University Hospital Coventry, which was opened in 2006 as a 1,250 bed 'super hospital', funded by a private finance initiative (PFI) scheme.[165]

Electricity

[edit]Electricity was first supplied to Coventry in 1895 from Coventry power station off Sandy Lane adjacent to the canal (now Electric Wharf). A larger 130 MW power station was built at Longford in 1928, this operated until 1976, and was subsequently demolished.[166]

Waste management

[edit]

Coventry has an energy from waste incinerator[167] which burns rubbish from both Coventry and Solihull, producing electricity for the National Grid and some hot water that is used locally through the Heatline project.[168] Rubbish is still put into landfill.

- Many areas of Coventry have kerb-side plastic, metal (tins and cans), and paper recycling. Garden-green rubbish is collected and composted.

- Waste materials can be taken to the recycling depot, which is adjacent to the incineration unit.

- There are recycling points throughout the city for paper, glass recycling and metal / tin can recycling.

In October 2006, Coventry City Council signed the Nottingham Declaration, joining 130 other UK councils in committing to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of the council and to help the local community do the same.

Transport

[edit]Roads

[edit]Coventry is near to the M1, M6, M40, M45 and M69 motorways. The M45, which is situated a few miles to the south-east of the city, was opened in 1959 as a spur to the original section of the M1 motorway, which linked London with the Midlands. This was, in effect, the first motorway to serve Coventry, as the section of the M6 north of the city did not open until 1971 and the M69 between Coventry and Leicester opened five years later. The M40, which is connected to the city via the A46, is 12 miles (19 kilometres) south of the city centre, south of Warwick and gives the city's residents an alternative dual carriageway and motorway route to London.

It is served by the A45 and A46 dual carriageways. The A45 originally passed through the centre of the city, but was re-routed in the 1930s on the completion of the Coventry Southern Bypass, with westbound traffic heading in the direction of Birmingham and eastbound traffic in the direction of Northampton. The A46 was re-routed to the east of the city in 1989 on completion of the Coventry Eastern Bypass, which directly leads to the M6/M69 interchange. To the south, it gives a direct link to the M40, making use of the existing Warwick and Kenilworth bypasses.

Coventry has a dual-carriageway Ring Road (officially road number A4053) that is 2.25 miles long.[169] It loops around the city centre and roughly follows the lines of the old city walls.[170] The Ring Road began construction in the late 1950s, the first stretch was opened in 1962,[169] and it was finally completed in 1974. Ring Road junctions have all been numbered since the 1980s.[171] The road has a reputation for being difficult to navigate. A single street of Victorian terraces, Starley Road, remains inside the ring road after a campaign by residents prevented its demolition in the 1980s.[172]

Phoenix Way, a dual-carriageway running north–south completed in 1995, links the city centre with the M6 motorway.

Railway

[edit]

Coventry railway station is a principal stop on the West Coast Main Line; it is served by three train operating companies:

- Avanti West Coast operates inter-city services between London Euston, Birmingham New Street, Wolverhampton, Preston, Carlisle, Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Waverley[173]

- CrossCountry provides services between Manchester Piccadilly and Bournemouth, via Birmingham New Street, Reading and Southampton Central[174]

- London Northwestern (a trade name of West Midlands Trains) provides stopping services between London Euston and Birmingham New Street, via Rugeley. There are also services between Nuneaton and Leamington Spa.[175]

Coventry has also three suburban railway stations at Coventry Arena, Canley and Tile Hill. Coventry Arena, serving the north of city on the Coventry to Nuneaton Line, opened in January 2016 primarily for the Ricoh Arena where football, rugby matches and concerts take place.

Light rail

[edit]A light rail system is planned for Coventry, known as Coventry Very Light Rail. The first vehicle came off the production line in March 2021 and the first line, to University Hospital Coventry, was proposed to be operational by 2024.[176]

Buses

[edit]

Bus operators in Coventry include National Express Coventry, Arriva Midlands and Stagecoach in Warwickshire. Pool Meadow bus station is the main bus and coach interchange in the city centre. Coventry has a single Park and Ride service from War Memorial Park served by Stagecoach in Warwickshire. From Pool Meadow, there are national coach links to major towns and cities, seaside towns, ferry ports and events with National Express, with four stands (A, B, C and D).[177]

Coventry aims to have all of its buses powered by electricity by 2025.[178]

Air

[edit]The nearest major airport is Birmingham Airport, some 11 miles (18 km) to the west of the city. Coventry Airport, located 5 miles (8 km) south of the city centre in Baginton, is now used for general aviation only.[179]

Water

[edit]

The Coventry Canal terminates near the city centre at Coventry Canal Basin and is navigable for 38 miles (61 km) to Fradley Junction in Staffordshire.[180] The canal engineer James Brindley was responsible for the initial planning of the canal.[181] The Coventry Canal Society was formed in 1957.

Accent

[edit]Origins

[edit]Coventry in a linguistic sense looks both ways, towards both the 'West' and 'East' Midlands.[182] One thousand years ago, the extreme west of Warwickshire (what today we would designate Birmingham and the Black Country) was separated from Coventry and east Warwickshire by the forest of Arden, with resulting inferior means of communication.[182] The west Warwickshire settlements too were smaller in comparison to Coventry which, by the 14th century, was England's third city.[182] Even as far back as Anglo-Saxon times Coventry—situated as it was, close to Watling Street—was a trading and market post between King Alfred's Saxon Mercia and Danelaw England with a consequent merging of dialects.[183]

Coventry and Birmingham accents

[edit]Phonetically the accent of Coventry, like the perhaps better known accent of Birmingham, is similar to Northern English with respect to its system of short vowels. For example, it lacks the BATH/TRAP (Cov. /baθ/, Southern /bɑːθ/) and FOOT/STRUT (Cov. /strʊt/, Southern /strʌt/) splits.[183] Yet the longer vowels in the accent also contain traces of Estuary English such as a partial implementation of the London diphthong shift, increasingly so amongst the young since 1950. We also see other Estuary English features, such as a /l/-vocalisation whereby words such as 'milk' come to be pronounced as /mɪʊk/.[183] However, the distinction between Coventry and Birmingham accents is often overlooked. Certain features of the Birmingham accent (e.g. occasional tapping of prevocalic /r/ in words such as 'crack') stop starkly as one moves beyond Solihull in the general direction of Coventry, a possible approximation of the 'Arden Forest' divide perhaps. In any case, Coventry sits right at a dialectal crossroads, very close to isoglosses that generally delineate 'Northern' and 'Southern' dialects, exhibiting features from both sides of the divide.[183]

Coventry accent on television

[edit]The BBC's 2009 documentary The Bombing of Coventry contained interviews with Coventrians. Actress Becci Gemmell, played Coventry character Joyce in the BBC drama Land Girls.[184]

Honours

[edit]A minor planet, 3009 Coventry, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1973, is named after the city.[185]

Education

[edit]Universities and further education colleges

[edit]