Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kakuro

View on Wikipedia

Kakuro or Kakkuro or Kakoro (Japanese: カックロ) is a kind of logic puzzle that is often referred to as a mathematical transliteration of the crossword. Kakuro puzzles are regular features in many math-and-logic puzzle publications across the world. In 1966,[1] Canadian Jacob E. Funk, an employee of Dell Magazines, came up with the original English name Cross Sums [2] and other names such as Cross Addition have also been used, but the Japanese name Kakuro, abbreviation of Japanese kasan kurosu (加算クロス, "addition cross"), seems to have gained general acceptance and the puzzles appear to be titled this way now in most publications. The popularity of Kakuro in Japan is immense, second only to Sudoku among Nikoli's famed logic-puzzle offerings.[2]

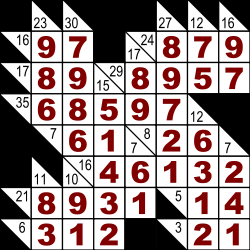

The canonical Kakuro puzzle is played in a grid of filled and barred cells, "black" and "white" respectively. Puzzles are usually 16×16 in size, although these dimensions can vary widely. Apart from the top row and leftmost column which are entirely black, the grid is divided into "entries"—lines of white cells—by the black cells. The black cells contain a diagonal slash from upper-left to lower-right and a number in one or both halves, such that each horizontal entry has a number in the half-cell to its immediate left and each vertical entry has a number in the half-cell immediately above it. These numbers, borrowing crossword terminology, are commonly called "clues".

The objective of the puzzle is to insert a digit from 1 to 9 inclusive into each white cell so that the sum of the numbers in each entry matches the clue associated with it and that no digit is duplicated in any entry. It is that lack of duplication that makes creating Kakuro puzzles with unique solutions possible. Like Sudoku, solving a Kakuro puzzle involves investigating combinations and permutations. There is an unwritten rule for making Kakuro puzzles that each clue must have at least two numbers that add up to it, since including only one number is mathematically trivial when solving Kakuro puzzles.

At least one publisher[3] includes the constraint that a given combination of numbers can only be used once in each grid, but still markets the puzzles as plain Kakuro.

Some publishers prefer to print their Kakuro grids exactly like crossword grids, with no labeling in the black cells and instead numbering the entries, providing a separate list of the clues akin to a list of crossword clues. (This eliminates the row and column that are entirely black.) This is purely an issue of image and does not affect either the solution nor the logic required for solving.

In discussing Kakuro puzzles and tactics, the typical shorthand for referring to an entry is "(clue, in numerals)-in-(number of cells in entry, spelled out)", such as "16-in-two" and "25-in-five". The exception is what would otherwise be called the "45-in-nine"—simply "45" is used, since the "-in-nine" is mathematically implied (nine cells is the longest possible entry, and since it cannot duplicate a digit it must consist of all the digits from 1 to 9 once). Both "43-in-eight" and "44-in-eight" are still frequently called as such, despite the "-in-eight" suffix being equally implied.

Solving techniques

[edit]Combinatoric techniques

[edit]Although brute-force guessing is possible, a more efficient approach is the understanding of the various combinatorial forms that entries can take for various pairings of clues and entry lengths. The solution space can be reduced by resolving allowable intersections of horizontal and vertical sums, or by considering necessary or missing values.

Those entries with sufficiently large or small clues for their length will have fewer possible combinations to consider, and by comparing them with entries that cross them, the proper permutation—or part of it—can be derived. The simplest example is where a 3-in-two crosses a 4-in-two: the 3-in-two must consist of "1" and "2" in some order; the 4-in-two (since "2" cannot be duplicated) must consist of "1" and "3" in some order. Therefore, their intersection must be "1", the only digit they have in common.

When solving longer sums there are additional ways to find clues to locating the correct digits. One such method would be to note where a few squares together share possible values thereby eliminating the possibility that other squares in that sum could have those values. For instance, if two 4-in-two clues cross with a longer sum, then the 1 and 3 in the solution must be in those two squares and those digits cannot be used elsewhere in that sum.[4]

When solving sums that have a limited number of solution sets then that can lead to useful clues. For instance, a 30-in-seven sum only has two solution sets: {1,2,3,4,5,6,9} and {1,2,3,4,5,7,8}. If one of the squares in that sum can only take on the values of {8,9} (if the crossing clue is a 17-in-two sum, for example) then that not only becomes an indicator of which solution set fits this sum, it eliminates the possibility of any other digit in the sum being either of those two values, even before determining which of the two values fits in that square.

Another useful approach in more complex puzzles is to identify which square a digit goes in by eliminating other locations within the sum. If all of the crossing clues of a sum have many possible values, but it can be determined that there is only one square that could have a particular value which the sum in question must have, then whatever other possible values the crossing sum would allow, that intersection must be the isolated value. For example, a 36-in-eight sum must contain all digits except 9. If only one of the squares could take on the value of 2 then that must be the answer for that square.

Box technique

[edit]A "box technique" can also be applied on occasion, when the geometry of the unfilled white cells at any given stage of solving lends itself to it: by summing the clues for a series of horizontal entries (subtracting out the values of any digits already added to those entries) and subtracting the clues for a mostly overlapping series of vertical entries, the difference can reveal the value of a partial entry, often a single cell. This technique works because addition is both associative and commutative.

It is common practice to mark potential values for cells in the cell corners until all but one have been proven impossible; for particularly challenging puzzles, sometimes entire ranges of values for cells are noted by solvers in the hope of eventually finding sufficient constraints to those ranges from crossing entries to be able to narrow the ranges to single values. Because of space constraints, instead of digits, some solvers use a positional notation, where a potential numerical value is represented by a mark in a particular part of the cell, which makes it easy to place several potential values into a single cell. This also makes it easier to distinguish potential values from solution values.

Some solvers also use graph paper to try various digit combinations before writing them into the puzzle grids.

As in the Sudoku case, only relatively easy Kakuro puzzles can be solved with the above-mentioned techniques. Harder ones require the use of various types of chain patterns, the same kinds as appear in Sudoku (see Pattern-Based Constraint Satisfaction and Logic Puzzles[5]).

Mathematics of Kakuro

[edit]Mathematically, Kakuro puzzles can be represented as integer programming problems, and are NP-complete.[6] See also Yato and Seta, 2004.[7]

There are two kinds of mathematical symmetry readily identifiable in Kakuro puzzles: minimum and maximum constraints are duals, as are missing and required values.

All sum combinations can be represented using a bitmapped representation. This representation is useful for determining missing and required values using bitwise logic operations.

Popularity

[edit]Kakuro puzzles appear in nearly 100 Japanese magazines and newspapers. Kakuro remained the most popular logic puzzle in Japanese printed press until 1992, when Sudoku took the top spot.[8] In the UK, they first appeared in The Guardian, with The Telegraph and the Daily Mail following.[9]

See also

[edit]- Killer Sudoku, a variant of Sudoku which is solved using similar techniques.

References

[edit]- ^ Timmerman, Charles (2006). The Everything Kakuro Challenge Book. Adams Media. p. ix. ISBN 9781598690576. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Kakuro history". Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Sudoku From Denksport". Keesing Group B.V. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Kakuro rules". Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Berthier, Denis (April 5, 2013). "Pattern-Based Constraint Satisfaction and Logic Puzzles". arXiv:1304.1628 [cs.AI].

- ^ Takahiro, Seta (February 5, 2002). "The complexities of puzzles, cross sum and their another solution problems (ASP)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Yato, Takayuki; Seta, Takahiro (2003). "Complexity and Completeness of Finding Another Solution and Its Application to Puzzles". IEICE Transactions on Fundamentals of Electronics, Communications and Computer Sciences. E86-A (5): 1052–1060.

- ^ "What is Kakuro". Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Kakuro History". Retrieved November 18, 2018.

External links

[edit]- The New Grid on the Block: The Guardian newspaper's introduction to Kakuro

- IAENG report on Kakuro

- Solve Kakuro puzzles online

Kakuro

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Overview

Kakuro is a logic-based puzzle that combines elements of crossword puzzles and numerical addition, often described as a "number crossword" or "cross-sum" puzzle.[1][2] It requires players to fill a grid with digits from 1 to 9, using clues that represent the sums of entries in horizontal and vertical runs, while adhering to constraints that prevent digit repetition within each run.[6] Unlike traditional crosswords that use letters and words, Kakuro emphasizes arithmetic and logical deduction, making it accessible yet challenging for a wide range of skill levels.[2] The puzzle's grid structure resembles a crossword, featuring black cells that separate white cells into defined runs or "entries," with clues provided in the black cells adjacent to each run.[6] These clues, typically displayed with a diagonal line separating horizontal (down) and vertical (across) sums, indicate the total value that the digits in the corresponding run must add up to.[1] Players must select unique digits for each run to satisfy the sum without reusing any number within that sequence, ensuring that intersecting runs across the grid are consistent.[6] Puzzles vary in size and difficulty, from small grids solvable in minutes to larger ones requiring hours of deduction.[1] Kakuro's appeal lies in its language-independent nature, relying solely on numbers and logic, which has contributed to its global popularity in print media, apps, and online platforms.[2] Variants such as "Holey Kakuro" or "Diamond Kakuro" introduce modifications like irregular shapes or additional constraints, but the core mechanics remain centered on sum-based filling and non-repetition.[1] This design promotes systematic problem-solving, blending simple arithmetic with combinatorial constraints to create uniquely solvable puzzles.[6]History

Kakuro, originally known as Cross Sums, was invented by Canadian Jacob E. Funk, a building constructor, and first published in the United States in 1950 in the April/May issue of Official Crossword Puzzles magazine, a publication by Dell Magazines.[3] The puzzle quickly became a regular feature in Dell's math and logic publications, where it was presented as a numerical equivalent to crosswords, emphasizing addition constraints across black and white cells.[3] In 1980, the puzzle was introduced to Japan by Maki Kaji, president of the puzzle company Nikoli, who adapted it and named it kasan kurosu, combining the Japanese words for "addition" (kasan) and "cross" (kurosu).[3][7] This version was shortened to kakuro for simplicity and began appearing in Japanese puzzle magazines published by Nikoli, gaining steady popularity among enthusiasts.[8][7] The puzzle's international breakthrough occurred in the mid-2000s, following the global Sudoku craze, with kakuro appearing in major newspapers and magazines worldwide under various names like Cross Sums or simply Kakuro.[8] By 2005, it had become a bestseller in puzzle books and online formats, solidifying its status as a staple logic game.[7]Rules and Gameplay

Grid Structure

A Kakuro puzzle is presented on a grid composed of black and white cells, resembling a crossword layout where black cells act as barriers to divide the grid into horizontal and vertical runs of white cells. The white cells are the ones to be filled with digits from 1 to 9, while black cells remain empty of digits but may contain clues. This structure ensures that the puzzle forms interlocking sequences, similar to words in a crossword, but focused on numerical sums rather than letters.[2][1] The core of the grid lies in the runs, which are contiguous sequences of two or more white cells aligned either horizontally or vertically, separated by black cells. Each run must be filled with distinct digits from 1 to 9, with no repetition allowed within the same run, though the same digit may appear in different runs. Runs vary in length from 2 to 9 cells, as longer sequences would require repeating digits within the run, which is not permitted. This design promotes logical deduction by limiting possibilities based on sum constraints and uniqueness rules.[9][10] Clues are embedded within certain black cells adjacent to the runs they define, typically displayed in a split format—often as two small numbers in a diagonal arrangement within the black cell—to indicate the required sum for the horizontal run to the right and the vertical run below. For instance, a black cell might show "15" and "\9" to clue a horizontal sum of 15 and a vertical sum of 9. These clues are always positive integers greater than 1 for runs of length 2 or more, and the maximum sum for a 9-cell run is 45, achieved by using digits 1 through 9.[9][1] Standard Kakuro grids are commonly 16 by 16 cells in size, though variations from 9 by 9 to larger formats exist to accommodate different difficulty levels. The layout is irregular, with black cells forming a non-uniform pattern that creates multiple intersecting runs, ensuring the puzzle's solvability relies on the global consistency of all sums. This asymmetrical structure distinguishes Kakuro from uniform grids like Sudoku, emphasizing cross-sum interdependencies.[2][9]Clues and Constraints

In Kakuro puzzles, clues are provided in the form of sum values placed within specially designated black cells, which are typically divided by a diagonal line to distinguish between horizontal (across) and vertical (down) entries. The number above the diagonal indicates the required sum for the adjacent horizontal run of white cells to its right, while the number below the diagonal specifies the sum for the vertical run of white cells below it. These clues guide the placement of digits such that the total of the digits in each run precisely matches the given value.[6][11] The primary constraints revolve around the use of digits from 1 to 9, with no digit permitted to repeat within the same across or down entry, ensuring that each run functions like a unique combination of distinct numbers. For instance, a clue of 4 for a two-cell entry can only be satisfied by 1+3 or 3+1, not 2+2, due to the no-repetition rule. Additionally, an unwritten but standard convention in puzzle construction requires that every clue corresponds to at least two white cells, preventing trivial single-digit solutions and maintaining the puzzle's logical challenge.[6][12][11] These constraints extend to the overall grid integrity, where black cells act as barriers, isolating entries so that digits may repeat across different runs in the same row or column only if separated by a black cell. Puzzles are designed to have a unique solution achievable through logical deduction, without guessing, and all white cells must be filled to satisfy every clue simultaneously.[6][12]Solving Techniques

Basic Methods

Basic methods for solving Kakuro puzzles begin with identifying runs—sequences of empty cells in a row or column bounded by black cells or the grid edge—where the sum of distinct digits from 1 to 9 must equal the provided clue without repetition within the run.[13][14] For short runs of two or three cells, many clues have limited or unique combinations, allowing immediate deductions; for example, a two-cell clue of 3 can only be filled with 1 and 2, while a three-cell clue of 6 must be 1, 2, and 3.[13][15] These "restricted blocks" form the foundation, as they restrict possible digits early and propagate solutions across the grid.[15] A core technique is cross-referencing intersections between horizontal (across) and vertical (down) runs sharing a cell, which narrows candidates to common digits across both clues.[14][16] For instance, if a cell lies in a two-cell across run summing to 16 (possible pairs: 7+9 or 8+8, but duplicates forbidden, so 7+9) and a two-cell down run summing to 17 (8+9), the intersection must be 9, filling that cell and updating adjacent possibilities.[16] This method exploits the no-duplication rule to eliminate invalid options, such as rejecting a 9 in a three-cell run summing to 11 if it forces two 1s elsewhere in the run.[13] Pencil marking, or listing candidate digits for each empty cell based on its run's possible combinations, aids systematic elimination as cells are filled.[16] For a five-cell run summing to 33, valid sets include {3,6,7,8,9} or {4,5,7,8,9}; if one cell is known to be 4, the first set is eliminated, restricting others to {5,7,8,9}.[16] Repeating this process—deriving partitions of clues into distinct 1-9 digits and cross-checking—progressively fills cells until the puzzle resolves, emphasizing logical deduction over trial and error for basic solvability.[17][15]Advanced Strategies

Advanced strategies for solving Kakuro puzzles extend beyond identifying unique digit combinations for clues by leveraging intersections, contradictions, and structural patterns in the grid. One such technique involves calculating implicit sums across overlapping runs, where the total of multiple vertical or horizontal clues minus an intersecting run yields a constrained sum for remaining cells. For instance, if two vertical runs sum to 24 and share cells with a horizontal run of 16, the shared pair must sum to 8, eliminating duplicates like two 4s due to the no-repeat rule.[18] Another approach uses differences between intersecting sums to pinpoint cell values directly. By subtracting the sums of crossing runs—such as (21 + 10) minus (11 + 13)—solvers can determine a unique digit like 7 for the intersection cell, bypassing exhaustive enumeration. This method, often called difference cells, exploits the grid's layout to create virtual constraints.[19] Mathematical modeling treats the puzzle as a system of linear equations with inequality constraints (1 ≤ x ≤ 9, no repeats), solvable via algebraic reduction. Representing cells as variables and clues as equations allows elimination of null-space solutions through templates that isolate subproblems, such as self-contained blocks where interlocking clues form independent mini-puzzles. These blocks can be solved separately and replaced with effective single values, dividing larger grids into manageable parts.[17] Pattern-based constraint propagation draws from logic puzzle theory, applying chains like bivalue-chains or whips to eliminate candidates without trial-and-error. In Kakuro, a whip—a loopless chain linking incompatible candidates—resolves non-binary sum constraints by identifying contradictions in sectors, such as magic sectors with unique digit sets (34 predefined cases). Generalized labels (g-labels) group candidates for stronger patterns like g-whips, enabling eliminations in complex intersections. These methods, formalized in intuitionistic logic, achieve confluence for efficient resolution.[20] For computational solving, Kakuro is formulated as a constraint satisfaction problem (CSP) using backtracking with heuristics like minimum remaining values (MRV), which prioritizes cells with fewest options. Forward checking prunes domains post-assignment, while local i-consistency computes min-max bounds (e.g., max value = sum - i(i-1)/2 for i cells) to reduce search space. Mixed integer linear programming (MILP) models cells with binary variables X_{i,j,k} (1 if digit k is placed) and constraints for uniqueness and sums, solvable via optimization solvers that presolve to cut variables significantly (e.g., removing over 60% in large grids).[21][22]Mathematical Aspects

Combinatorial Properties

Kakuro's combinatorial structure centers on the runs—sequences of contiguous white cells in horizontal or vertical directions—each assigned a sum clue ranging from 3 to 45 and filled with distinct digits from 1 to 9 within each run. For a run of length (where ), the possible sums range from the minimum (using the smallest digits) to the maximum (using the largest digits), ensuring all valid fillings are permutations of distinct subsets that achieve the clue. This setup creates a constrained permutation problem, where the total number of valid fillings for a single run depends on the clue and length, often computed via generating functions: the number of unordered subsets summing to the clue is the coefficient of in , multiplied by for ordered arrangements.[23] The number of possible combinations varies significantly by run length and sum, with shorter runs having fewer options that aid in solving. For instance, a length-2 run with sum 3 has only one unordered set and 2 permutations, while a length-4 run with sum 20 has 12 unordered sets and 288 permutations. Longer runs, such as length 9, permit up to permutations for the full set summing to 45, though specific clues reduce this sharply. These combinations form the building blocks of the puzzle, and their overlaps enforce global consistency through shared cells in intersecting runs.[23][24]| Run Length | Min Sum | Max Sum | Example: Max # Permutations (for min/max sum) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 17 | 2 (sum 3), 2 (sum 17) |

| 3 | 6 | 24 | 6 (sum 6), 6 (sum 24) |

| 4 | 10 | 30 | 24 (sum 10), 24 (sum 30) |

| 5 | 15 | 35 | 120 (sum 15), 120 (sum 35) |

| 9 | 45 | 45 | 362,880 (only possible sum) |