Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

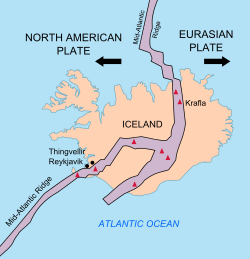

Krafla

View on WikipediaKrafla (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈkʰrapla] ⓘ) is a volcanic caldera of about 10 km (6.2 mi) in diameter with a 90 km (56 mi) long fissure zone. It is located in the north of Iceland in the Mývatn region and is situated on the Iceland hotspot atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which forms the divergent boundary between the North American Plate and the Eurasian Plate.[1] Its highest peak reaches up to 818 m (2,684 ft) and it is 2 km (1.2 mi) in depth. There have been 29 reported eruptions in recorded history.

Key Information

Overview

[edit]

Iceland sits astride the Mid-Atlantic Ridge; the western part of the island nation is part of the roughly westward-moving North American plate, while the eastern part of the island is part of the roughly eastward-moving Eurasian Plate. The north–south axis of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge splits Iceland in two, roughly north to south. Along this ridge many of Iceland's most active volcanoes are located; Krafla is one of these.[2]

Krafla includes the crater Víti [ˈviːtɪ], which contains a green lake. South of the Krafla area is Námafjall [ˈnauːmaˌfjatl̥], a mountain, at the foot of which is Hverir [ˈkʰvɛːrɪr̥], a geothermal area with boiling mudpools and steaming fumaroles.

History

[edit]

The Mývatn fires occurred between 1724 and 1729, when many of the fissure vents opened up. The lava fountains could be seen in the south of the island, and a lava flow destroyed three farms near the village of Reykjahlíð, although nobody was harmed.

Between 1975 and 1984, a series of volcanic events known as the Krafla fires took place within the Krafla caldera.[3] There were nine volcanic eruptions and fifteen uplift and subsidence events. During these events a large magma chamber was identified at depth by analysing the seismic activity. Some of the lava fountaining during these eruptions was caught on film by Maurice and Katia Krafft, and features in the 2022 film, Fire of Love.[4]

Since 1977 the Krafla area has been the source of the geothermal energy used by a 60 MWe power station. A survey undertaken in 2006 indicated very high temperatures at depths of between 3 and 5 kilometres (1.9 and 3.1 miles), and these favourable conditions led to the development of the first well from the Iceland Deep Drilling Project, IDDP-1, that found molten rhyolite magma 2.1 km (1.3 mi) deep beneath the surface in 2009.[5][6] The Krafla fires interrupted some of the geothermal drilling work in the area.

Krafla magma testbed

[edit]Following on from the encounter with molten rock during the drilling of IDDP-1, the Krafla Magma Testbed (KMT[7]) concept has been developed, which envisages the creation of an 'international magma observatory' and further scientific drilling at Krafla in order to deliberately drill into the magma body.[8][9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Krafla - Global Volcanism Program". Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Kious, W. Jacquelyne; Tilling, Robert I. (February 1996). "This Dynamic Earth: The Story of Plate Tectonics. Chapter 3: Understanding plate motions - Divergent boundaries". United States Geological Survey. USGS. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

The volcanic country of Iceland, which straddles the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, offers scientists a natural laboratory for studying on land the processes also occurring along the submerged parts of a spreading ridge. Iceland is splitting along the spreading center between the North American and Eurasian Plates, as North America moves westward relative to Eurasia.

- ^ "The Krafla fires: One of the largest volcanic eruptions of Iceland's modern history". Icelandmag.

- ^ "She fell in love with the majesty of volcanoes—and changed how science sees them". Science. January 9, 2023. Archived from the original on January 9, 2023.

- ^ http://www.iddp.is/ Iceland Deep Drilling Project

- ^ "Surprise magma pocket found in Iceland hints at more 'ticking time bombs'". Science. May 19, 2021. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021.

- ^ "Krafla Magma Testbed – Oficial Website – Krafla Magma Testbed".

- ^ Eichelberger, J. (June 25, 2019). "Planning an International Magma Observatory". Eos.

- ^ https://www.geothermal-energy.org/pdf/WGC/papers/WGC/2020/37027.pdf [bare URL PDF]

External links

[edit]- Krafla [1] in the Catalogue of Icelandic Volcanoes

- "Krafla". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- Volcanism

- Photos of Krafla and Reykjahlíð (among others)

- Univ. of Iceland: Information about Krafla

- Energy from magma at Krafla[permanent dead link]