Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Directional drilling

View on Wikipedia

Directional drilling (or slant drilling) is the practice of drilling non-vertical bores. It can be broken down into four main groups: oilfield directional drilling, utility installation directional drilling, directional boring (horizontal directional drilling - HDD), and surface in seam (SIS), which horizontally intersects a vertical bore target to extract coal bed methane.

History

[edit]Many prerequisites enabled this suite of technologies to become productive. Probably, the first requirement was the realization that oil wells, or water wells, do not necessarily need to be vertical. This realization was quite slow, and did not really grasp the attention of the oil industry until the late 1920s when there were several lawsuits alleging that wells drilled from a rig on one property had crossed the boundary and were penetrating a reservoir on an adjacent property.[citation needed] Initially, proxy evidence such as production changes in other wells was accepted, but such cases fueled the development of small diameter tools capable of surveying wells during drilling. Horizontal directional drill rigs are developing towards large-scale, micro-miniaturization, mechanical automation, hard stratum working, exceeding length and depth oriented monitored drilling.[1]

Measuring the inclination of a wellbore (its deviation from the vertical) is comparatively simple, requiring only a pendulum. Measuring the azimuth (direction with respect to the geographic grid in which the wellbore was running from the vertical), however, was more difficult. In certain circumstances, magnetic fields could be used, but would be influenced by metalwork used inside wellbores, as well as the metalwork used in drilling equipment. The next advance was in the modification of small gyroscopic compasses by the Sperry Corporation, which was making similar compasses for aeronautical navigation. Sperry did this under contract to Sun Oil (which was involved in a lawsuit as described above), and a spin-off company "Sperry Sun" was formed, which brand continues to this day,[when?][clarification needed] absorbed into Halliburton. Three components are measured at any given point in a wellbore in order to determine its position: the depth of the point along the course of the borehole (measured depth), the inclination at the point, and the magnetic azimuth at the point. These three components combined are referred to as a "survey". A series of consecutive surveys are needed to track the progress and location of a wellbore.

Prior experience with rotary drilling had established several principles for the configuration of drilling equipment down hole ("bottom hole assembly" or "BHA") that would be prone to "drilling crooked hole" (i.e., initial accidental deviations from the vertical would be increased). Counter-experience had also given early directional drillers ("DD's") principles of BHA design and drilling practice that would help bring a crooked hole nearer the vertical.[citation needed]

In 1934, H. John Eastman and Roman W. Hines of Long Beach, California, became pioneers in directional drilling when they and George Failing of Enid, Oklahoma, saved the Conroe, Texas, oil field. Failing had recently patented a portable drilling truck. He had started his company in 1931 when he mated a drilling rig to a truck and a power take-off assembly. The innovation allowed rapid drilling of a series of slanted wells. This capacity to quickly drill multiple relief wells and relieve the enormous gas pressure was critical to extinguishing the Conroe fire.[2] In a May, 1934, Popular Science Monthly article, it was stated that "Only a handful of men in the world have the strange power to make a bit, rotating a mile below ground at the end of a steel drill pipe, snake its way in a curve or around a dog-leg angle, to reach a desired objective." Eastman Whipstock, Inc., would become the world's largest directional company in 1973.[citation needed]

Combined, these survey tools and BHA designs made directional drilling possible, but it was perceived as arcane. The next major advance was in the 1970s, when downhole drilling motors (aka mud motors, driven by the hydraulic power of drilling mud circulated down the drill string) became common. These allowed the drill bit to continue rotating at the cutting face at the bottom of the hole, while most of the drill pipe was held stationary. A piece of bent pipe (a "bent sub") between the stationary drill pipe and the top of the motor allowed the direction of the wellbore to be changed without needing to pull all the drill pipe out and place another whipstock. Coupled with the development of measurement while drilling tools (using mud pulse telemetry, networked or wired pipe or electromagnetism (EM) telemetry, which allows tools down hole to send directional data back to the surface without disturbing drilling operations), directional drilling became easier.

Certain profiles cannot be easily drilled while the drill pipe is rotating. Drilling directionally with a downhole motor requires occasionally stopping rotation of the drill pipe and "sliding" the pipe through the channel as the motor cuts a curved path. "Sliding" can be difficult in some formations, and it is almost always slower and therefore more expensive than drilling while the pipe is rotating, so the ability to steer the bit while the drill pipe is rotating is desirable. Several companies have developed tools which allow directional control while rotating. These tools are referred to as rotary steerable systems (RSS). RSS technology has made access and directional control possible in previously inaccessible or uncontrollable formations.

Benefits

[edit]Wells are drilled directionally for several purposes:

- Increasing the exposed section length through the reservoir by drilling through the reservoir at an angle.

- Drilling into the reservoir where vertical access is difficult or not possible. For instance an oilfield under a town, under a lake, or underneath a difficult-to-drill formation.

- Allowing more wellheads to be grouped together on one surface location can allow fewer rig moves, less surface area disturbance, and make it easier and cheaper to complete and produce the wells. For instance, on an oil platform or jacket offshore, 40 or more wells can be grouped together. The wells will fan out from the platform into the reservoir(s) below. This concept is being applied to land wells, allowing multiple subsurface locations to be reached from one pad, reducing costs.

- Drilling along the underside of a reservoir-constraining fault allows multiple productive sands to be completed at the highest stratigraphic points.

- Drilling a "relief well" to relieve the pressure of a well producing without restraint (a "blowout"). In this scenario, another well could be drilled starting at a safe distance away from the blowout, but intersecting the troubled wellbore. Then, heavy fluid (kill fluid) is pumped into the relief wellbore to suppress the high pressure in the original wellbore causing the blowout.

Most directional drillers are given a blue well path to follow that is predetermined by engineers and geologists before the drilling commences. When the directional driller starts the drilling process, periodic surveys are taken with a downhole instrument to provide survey data (inclination and azimuth) of the well bore.[3] These pictures are typically taken at intervals between 10 and 150 meters (33 and 492 feet), with 30 meters (98 feet) common during active changes of angle or direction, and distances of 60–100 meters (200–330 feet) being typical while "drilling ahead" (not making active changes to angle and direction). During critical angle and direction changes, especially while using a downhole motor, a measurement while drilling (MWD) tool will be added to the drill string to provide continuously updated measurements that may be used for (near) real-time adjustments.

This data indicates if the well is following the planned path and whether the orientation of the drilling assembly is causing the well to deviate as planned. Corrections are regularly made by techniques as simple as adjusting rotation speed or the drill string weight (weight on bottom) and stiffness, as well as more complicated and time-consuming methods, such as introducing a downhole motor. Such pictures, or surveys, are plotted and maintained as an engineering and legal record describing the path of the well bore. The survey pictures taken while drilling are typically confirmed by a later survey in full of the borehole, typically using a "multi-shot camera" device.

The multi-shot camera advances the film at time intervals so that by dropping the camera instrument in a sealed tubular housing inside the drilling string (down to just above the drilling bit) and then withdrawing the drill string at time intervals, the well may be fully surveyed at regular depth intervals (approximately every 30 meters (98 feet) being common, the typical length of 2 or 3 joints of drill pipe, known as a stand, since most drilling rigs "stand back" the pipe withdrawn from the hole at such increments, known as "stands").

Drilling to targets far laterally from the surface location requires careful planning and design. The current record holders manage wells over 10 km (6.2 mi) away from the surface location at a true vertical depth (TVD) of only 1,600–2,600 m (5,200–8,500 ft).[4]

This form of drilling can also reduce the environmental cost and scarring of the landscape. Previously, long lengths of landscape had to be removed from the surface. This is no longer required with directional drilling.

Disadvantages

[edit]

Until the arrival of modern downhole motors and better tools to measure inclination and azimuth of the hole, directional drilling and horizontal drilling was much slower than vertical drilling due to the need to stop regularly and take time-consuming surveys, and due to slower progress in drilling itself (lower rate of penetration). These disadvantages have shrunk over time as downhole motors became more efficient and semi-continuous surveying became possible.

What remains is a difference in operating costs: for wells with an inclination of less than 40 degrees, tools to carry out adjustments or repair work can be lowered by gravity on cable into the hole. For higher inclinations, more expensive equipment has to be mobilized to push tools down the hole.

Another disadvantage of wells with a high inclination was that prevention of sand influx into the well was less reliable and needed higher effort. Again, this disadvantage has diminished such that, provided sand control is adequately planned, it is possible to carry it out reliably.

Stealing oil

[edit]In 1990, Iraq accused Kuwait of stealing Iraq's oil through slant drilling.[5] The United Nations redrew the border after the 1991 Gulf war, which ended the seven-month Iraqi occupation of Kuwait. As part of the reconstruction, 11 new oil wells were placed among the existing 600. Some farms and an old naval base that used to be in the Iraqi side became part of Kuwait.[6]

In the mid-twentieth century, a slant-drilling scandal occurred in the huge East Texas Oil Field.[7]

New technologies

[edit]Between 1985 and 1993, the Naval Civil Engineering Laboratory (NCEL) (now the Naval Facilities Engineering Service Center (NFESC)) of Port Hueneme, California developed controllable horizontal drilling technologies.[8] These technologies are capable of reaching 10,000–15,000 ft (3,000–4,600 m) and may reach 25,000 ft (7,600 m) when used under favorable conditions.[9]

Techniques

[edit]Wellbore Surveys

[edit]Specialized tools determine the wellbore's deviation from vertical (inclination) and its directional orientation (azimuth). This data is vital for trajectory adjustments. These surveys are taken at regular intervals (e.g., every 30–100 meters) to track the wellbore's progress in real time. In critical sections, measurement while drilling (MWD) tools provide continuous downhole measurements for immediate directional corrections as needed. MWD uses gyroscopes, magnetometers, and accelerometers to determine borehole inclination and azimuth while the drilling is being done.

Trajectory Control

[edit]- Bottom Hole Assembly (BHA): The configuration of drilling equipment near the drill bit (BHA) profoundly influences drilling direction. BHAs can be tailored to promote straight drilling or induce deviations.

- Downhole Motors: Specialized mud motors rotate only the drill bit, allowing controlled changes in direction while the majority of the drill string remains stationary.

- Rotary Steerable Systems (RSS): Advanced RSS technology enables steering even while the entire drill string is rotating, ensuring greater efficiency and control.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Development tendency of horizontal directional drilling". DC Solid control. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Technology and the "Conroe Crater"". American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Glossary of geo-steering terms". 26 August 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Maersk drills longest well at Al Shadeen". The Gulf Times. 21 May 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "How the Gulf Crisis Began and Ended (The Gulf Crisis and Japan's Foreign Policy)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Iraq to Reopen Embassy in Kuwait". ABC Inc. 4 September 2005. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Julia Cauble Smith (12 June 2010). "East Texas Oilfield". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Horizontal Drilling System (HDS) Field Test Report - FY 91

- ^ "Horizontal Drilling System (HDS) Operations Theory Report". Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

External links

[edit]- "Slanted Oil Wells, Work New Marvels" Popular Science, May 1934, early article on the drilling technology

- "Technology and the Conroe Crater" American Oil & Gas Historical Society

- Short video explaining horizontal drilling for gas extraction from oil shale. (American Petroleum Institute)

- A video depicting horizontal shale drilling can be seen here.

- "Mechanical Mole Bores Crooked Wells." Popular Science, June 1942, pp. 94–95.

- The unsung masters of the oil industry 21 July 2012 The Economist

Directional drilling

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Principles

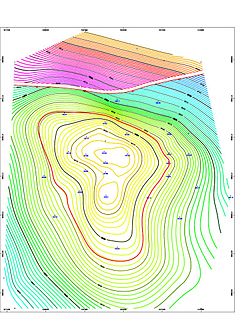

Directional drilling is the intentional deviation of a borehole from vertical alignment to follow a predetermined subsurface path, enabling access to hydrocarbon reservoirs laterally offset from the drilling rig's surface location. This technique contrasts with conventional vertical drilling by incorporating controlled changes in well inclination (angle from vertical) and azimuth (compass direction), typically starting with a vertical section followed by a kickoff point where deviation begins. The primary objective is to intersect specific targets, such as oil or gas deposits, that are inaccessible via straight vertical bores due to geological structures like faults or depleted vertical zones.[1][10] The core principles of directional drilling revolve around precise trajectory control and real-time surveying to maintain the planned well path. Trajectory planning defines the well as a three-dimensional curve in cylindrical coordinates: measured depth (along the borehole), true vertical depth, departure (horizontal offset), inclination, and azimuth. Deviation is induced by applying lateral forces to the drill bit using downhole tools, such as positive-displacement mud motors that rotate the bit independently of the drill string or whipstocks that sidetrack the borehole. Build rates, typically 2–5 degrees per 100 feet of measured depth in conventional applications, quantify the curvature, with dogleg severity (DLS) calculated as the angle change per unit length to assess tortuosity and potential drilling challenges like hole cleaning or torque.[1][11] Surveying underpins these principles through measurement-while-drilling (MWD) systems, which employ inclinometers, magnetometers, and gyroscopes to provide continuous data on position, orientation, and toolface (bit direction relative to high side). This enables adjustments via surface commands or downhole automation, minimizing deviation from the target. Error models, such as the minimum curvature method, propagate survey uncertainties to predict positional ellipse of uncertainty, ensuring the well reaches targets within tolerances often under 10 meters at depths exceeding 10,000 feet. These methods prioritize mechanical efficiency and formation stability, as excessive curvature can increase equivalent circulating density and risk stuck pipe, while precise control reduces overall drilling costs by up to 30% compared to multiple vertical wells.[1][11]Types and Classifications

Directional drilling is classified primarily by well trajectory profiles, deviation angles, and operational objectives, distinguishing it from vertical drilling where the borehole aligns perpendicular to the surface. Trajectory-based categories include Type 1 (minimal deviation with straight sections), Type 2 (S-shaped profiles with build and drop sections for crossing under obstacles), Type 3 (horizontal profiles exceeding 80° inclination for maximum reservoir exposure), and Type 4 (complex or multilateral configurations).[12] These profiles enable targeted access to subsurface reservoirs while mitigating geological challenges like faults or depleted zones.[1] Common types encompass sidetracking, where a deviated path branches from an existing wellbore to circumvent obstructions or tap adjacent pay zones, often initiated via whipstock tools at depths exceeding 1,000 meters.[12] Build-and-hold profiles, known as "J-type" wells, involve an initial vertical section followed by a gradual angle build to a stable inclination, typically 30°–60°, before holding course to intersect targets up to several kilometers offset.[13][12] In contrast, "S-type" wells add a drop-angle phase after the hold, returning toward verticality to facilitate multiple reservoir penetrations or surface exits, with build rates controlled at 2°–4° per 30 meters of drilled depth.[12] Horizontal directional drilling achieves near-90° deviation, maximizing lateral reservoir contact—often 1,000–3,000 meters horizontally—to enhance production rates by factors of 5–10 compared to vertical wells in thin formations.[13][14] Extended-reach drilling (ERD) extends this horizontally beyond 10 kilometers from the surface location, employing high-torque rotary steerable systems to maintain trajectories in challenging environments like offshore platforms, with step-out ratios (horizontal-to-vertical depth) surpassing 3:1.[1][15] Multilateral wells branch multiple lateral sections from a main bore, classified by junction complexity (e.g., Level 1: open hole without pressure isolation; Level 5: fully cased with selective access), enabling drainage of compartmentalized reservoirs and reducing surface footprints.[1][12] Deviation angles further classify wells: low-angle (<30° for sidetracks or relief wells), high-angle (30°–80° for slant or build profiles), and horizontal (>80°), with dogleg severity (change in inclination per 30 meters) limited to 3°–8° to avoid tool failures.[2] Short-radius drilling, a niche variant, uses articulated motors for tight turns (up to 90° per 10 meters), suited to re-entry scenarios but phased out in favor of rotary steerable systems since the 1990s due to wear issues.[1] These classifications prioritize causal factors like torque transmission, hole cleaning, and formation stability, with empirical data from field trials validating build rates and reach limits.[16]Historical Development

Early Innovations (1920s–1950s)

The recognition of unintended deviations in ostensibly vertical wells prompted the initial innovations in directional drilling during the 1920s, as surveyors measured inclinations up to 50 degrees using rudimentary tools like acid bottles and Totco's mechanical drift recorders.[4] In 1926, Sperry Corporation introduced gyroscopic surveying for precise inclination and azimuth measurements, while H. John Eastman developed magnetic single-shot and multi-shot instruments in 1929, employing compass needles and cameras to enable controlled deviation.[4][17] These advancements, patented by Eastman in 1930, marked the birth of intentional directional control, allowing drillers to steer boreholes rather than merely correct deviations.[18] The first deliberately deviated wells emerged in the late 1920s, utilizing hardwood wedges to offset the drill bit and induce curvature, with the inaugural horizontal petroleum well completed in 1929 at Texon, Texas.[4][19] Whipstocks—wedge-shaped devices lowered into the borehole, oriented, and anchored to deflect the bit—became the dominant method by the 1930s, evolving from early wooden forms to durable steel variants that facilitated sidetracking as a planned operation rather than a remedial fix.[4][1] Eastman's expertise culminated in 1934 when he drilled a precise relief well to intercept a blowout at Conroe, Texas, demonstrating directional drilling's reliability for high-stakes interventions.[17][4] Offshore applications accelerated adoption, with the first directionally controlled wells drilled from Huntington Beach, California, in 1930 to access subsea reservoirs onshore, followed by undersea deviations at Signal Hill, Long Beach, in 1933.[1][4] By the 1940s, stabilized rotary bottomhole assemblies incorporating drill collars and stabilizers emerged to manage inclination through weight-on-bit and rotary speed adjustments, enhancing predictability.[4] Whipstocks remained the primary steering tool through the early 1950s, though limitations in hard formations spurred mid-decade experiments with jetting bits featuring large nozzles for soft-ground deflection.[19] These techniques, grounded in empirical surveying and mechanical deflection, laid the foundation for scalable directional control despite challenges like toolface orientation via slide rules.[1]Expansion and Refinements (1960s–1990s)

In the 1960s, downhole mud motors gained widespread adoption for directional control in oil and gas wells, enabling operators to manage deviations more reliably than prior whipstock or jetting methods. These positive displacement motors, powered by drilling fluid, decoupled bit rotation from the drill string, allowing targeted trajectory adjustments while minimizing torque requirements.[4] The 1970s brought steerable configurations of these motors, such as bent-housing assemblies, which improved the efficiency of directional drilling for extended-reach and early horizontal applications. This period saw directional techniques applied to access bypassed reserves and sidetrack wells, with mud motors becoming standard for building angle without full drill string rotation. Positive displacement motors enhanced drilling rates and reduced wear, contributing to the viability of horizontal wells by the late decade.[20][21] Measurement-while-drilling (MWD) systems emerged in the late 1970s, providing real-time inclination, azimuth, and toolface data via mud-pulse telemetry, which transformed surveying from periodic wireline interruptions to continuous monitoring. Schlumberger performed the first commercial MWD operation in 1980 in the Gulf of Mexico, integrating sensors into the bottomhole assembly for immediate feedback on trajectory corrections.[22][23] Refinements in the 1980s included advanced steerable motors with adjustable bends and improved hydraulics, alongside logging-while-drilling (LWD) integration for formation evaluation during directional runs. By the 1990s, rotary steerable systems (RSS) were prototyped and field-tested, with early patents filed in 1985 and commercial systems enabling steering under continuous drill string rotation, which reduced tortuosity, enhanced hole cleaning, and supported longer horizontal laterals up to several thousand feet. These innovations expanded directional drilling's role in complex reservoirs, prioritizing mechanical reliability and data accuracy over empirical trial-and-error.[24]Shale Revolution and Modern Era (2000s–Present)

The shale revolution, commencing in the mid-2000s, represented a transformative phase for directional drilling, driven by the synergistic application of advanced horizontal drilling techniques and hydraulic fracturing to access previously uneconomic tight shale formations. Pioneering efforts by Mitchell Energy in the Barnett Shale of Texas during the late 1990s and early 2000s demonstrated viability, with widespread commercialization accelerating after 2005 as rotary steerable systems and improved mud motors enabled precise long-radius horizontal laterals exceeding 4,000 feet.[25] [26] This integration unlocked substantial natural gas reserves, propelling U.S. dry natural gas production from shale from 1.6 trillion cubic feet in 2000 to 23.5 trillion cubic feet by 2020, accounting for over 70% of total U.S. gas output.[27] By the late 2000s, horizontal directional drilling expanded into liquid-rich shale plays, notably the Bakken Formation in North Dakota and Eagle Ford in Texas, where shorter-radius builds and geosteering via real-time logging-while-drilling tools optimized reservoir contact. U.S. crude oil production, stagnant at around 5 million barrels per day in 2008, surged to 12.3 million barrels per day by 2019, with shale accounting for the majority of the increment through laterals often surpassing 10,000 feet.[28] [29] Horizontal wells comprised 96% of new shale oil wells by 2018, reflecting efficiency gains from multi-stage fracturing along extended horizontals that minimized surface footprints via multi-well pads.[27] Technological refinements in the 2010s, including electromagnetic telemetry and advanced measurement-while-drilling sensors powered by microchip progress, further reduced drilling times and costs, enabling operators to drill and complete wells in under 20 days compared to months earlier.[26] Into the 2020s, despite market volatility, U.S. shale output stabilized at record highs, with Permian Basin laterals averaging over 11,000 feet by 2023, supported by data analytics for predictive geosteering and enhanced recovery rates exceeding 10% of original oil in place in select plays.[30] These developments, rooted in iterative engineering rather than singular breakthroughs, have positioned the U.S. as the world's largest oil and gas producer, reshaping global energy dynamics through sustained technological iteration.[31]Technical Techniques

Well Trajectory Planning and Surveying

Well trajectory planning entails designing the borehole path to intersect a predetermined subsurface target, such as a hydrocarbon reservoir, while adhering to operational constraints like maximum dogleg severity (typically 3–8 degrees per 100 feet) and torque-and-drag limits.[32] This process integrates geological data, including fault locations and formation properties, to maximize reservoir exposure and avoid hazards like unstable zones or existing wellbores.[33] Advanced software, such as Petrel or WellArchitect, employs optimization algorithms to generate paths that balance reach, stability, and economic factors, often using 3D models derived from seismic surveys.[34] Real-time adjustments may occur based on updated geological insights during drilling.[35] Key parameters in planning include inclination (angle from vertical), azimuth (compass direction), measured depth (along-hole distance), and true vertical depth.[32] Anti-collision analysis uses ellipsoids of uncertainty—probabilistic volumes around the planned path—to ensure separation from offset wells, with minimum distances enforced per regulatory standards like those from the American Petroleum Institute.[36] Trajectory designs often incorporate build-hold-and-drop sections for horizontal wells, aiming for lateral displacements up to several miles from the surface location.[37] Well surveying measures the actual borehole position to verify adherence to the planned trajectory and enable corrections.[38] Surveys are conducted using measurement-while-drilling (MWD) tools, which provide real-time data on inclination, azimuth, and toolface orientation via magnetometers and accelerometers.[1] Gyroscopic surveys offer higher accuracy in magnetically disturbed environments, resolving positions to within 1-2 meters over thousands of feet.[39] The minimum curvature method dominates survey calculations, modeling the path as a smooth circular arc between consecutive survey stations to compute coordinates, northing, easting, and vertical displacement.[40] It applies a ratio factor derived from the dogleg angle (ΔMD × sin(ΔIncl/2) / (ΔIncl/2 in radians)) to interpolate positions accurately, outperforming tangential or average-angle methods by reducing cumulative errors in complex trajectories.[41] This method assumes constant curvature, validated empirically against actual well paths, and is implemented in industry software for anti-collision and volume calculations.[42] Survey frequency varies, typically every 30-90 feet in build sections, to maintain positional uncertainty below 5% of total depth.[43]Steering and Control Methods

Steering in directional drilling primarily relies on downhole tools that enable precise control of the well trajectory by altering the drill bit's path relative to the borehole. The two dominant modern methods are steerable mud motors, which use alternating sliding and rotating modes, and rotary steerable systems (RSS), which maintain continuous drill string rotation during steering.[1][44] These approaches integrate with measurement-while-drilling (MWD) tools for real-time feedback on inclination, azimuth, and toolface orientation, allowing adjustments without frequent trips out of the hole.[45] Steerable mud motors, also known as positive displacement motors (PDMs), power the bit using hydraulic energy from drilling mud circulated through a rotor-stator assembly, independent of drill string rotation.[1] A bent housing in the motor assembly tilts the bit axis at a fixed angle (typically 1–3 degrees), creating an offset that builds curvature when oriented correctly.[45] In sliding mode, the drill string is held stationary while mud flow rotates the bit, enabling steering by aligning the toolface (the bend's high side) toward the desired direction via MWD data; this mode achieves dogleg severities up to 10°/30 m but can lead to poor hole cleaning and stick-slip issues due to lack of rotation.[45][1] In rotating mode, the surface rotary table or top drive spins the entire string (50–80 RPM), superimposing rotation on the motor's action to drill straighter sections with improved borehole quality and reduced tortuosity.[45] Trajectory control depends on factors like bend angle, stabilizer placement (forming three tangency points for arc definition), and mud weight, with MWD enabling geosteering by monitoring formation properties.[45] Rotary steerable systems represent an advancement over mud motors by permitting full drill string rotation during directional control, which enhances rate of penetration (ROP), reduces drag in extended-reach wells, and produces smoother boreholes with lower tortuosity.[44] RSS achieve this through closed-loop automation using downhole sensors and mud-pulse telemetry to adjust steering in real time, supporting lateral-to-vertical depth ratios up to 13:1.[44] They are categorized into point-the-bit systems, which dynamically tilt or reorient the bit relative to the housing (e.g., via eccentric mechanisms), and push-the-bit systems, which apply lateral force to the borehole wall using extendable pads (often three, spaced 120° apart) to bias the bit sideways.[44][46] Point-the-bit designs, such as those using rotating housings, minimize side forces for better stability in hard formations, while push-the-bit pads generate doglegs up to 18°/30 m but may increase vibrations or wear in softer rocks.[1][46] Hybrid variants combine elements for versatility, though RSS tools cost 3–4 times more than mud motors due to complexity.[44] Older or specialized techniques include whipstocks, which deploy a wedge-shaped tool to deflect the bit for sidetracking, and jetting, where high-pressure mud nozzles erode formation in soft, unconsolidated zones to initiate bends.[1] These are less common in modern operations, supplanted by motor and RSS methods for their efficiency in controlled, real-time steering. Overall control integrates logging-while-drilling (LWD) data for geosteering, ensuring the trajectory intersects target reservoirs while avoiding faults or hazards.[1][44]Tools and Equipment

The bottom hole assembly (BHA) forms the core of directional drilling equipment, comprising heavy-walled components positioned above the drill bit to apply weight, provide rigidity, and house steering and measurement tools. Key BHA elements include drill collars, which supply axial load to the bit and resist buckling in deviated sections; stabilizers, which contact the borehole wall to control trajectory and prevent inadvertent deviation; and subs or crossovers for connecting dissimilar tools.[47][48] In directional applications, the BHA is configured for build, hold, or drop tendencies, such as fulcrum assemblies with a bent sub above stabilizers to initiate deviation via side-cutting tendencies.[49] Steering mechanisms within the BHA enable precise control of well path deviation. Positive displacement mud motors, powered by drilling fluid flow, rotate the bit independently of the surface string, allowing angled housings (typically 1-3° bend) to steer by orienting the tool face.[50] These motors achieve dogleg severities up to 10°/100 ft in soft formations but require periodic sliding, which reduces penetration rates and risks hole spiraling.[51] Rotary steerable systems (RSS) address these limitations by enabling continuous drill string rotation while applying directional force via pads, cams, or internal biases, sustaining rates of penetration 20-50% higher than mud motors in many cases.[52] RSS tools, such as push-the-bit or point-the-bit designs, have become standard for extended-reach wells exceeding 10,000 ft laterally since their commercial deployment in the late 1990s.[44] Surveying and telemetry tools integrate into the BHA for real-time trajectory monitoring. Measurement-while-drilling (MWD) systems use inclinometers, magnetometers, and gyroscopes to measure inclination, azimuth, tool face angle, and build rates, transmitting data via mud pulse telemetry at depths up to 30,000 ft.[53] These tools achieve survey accuracies of ±0.1° in inclination and ±1° in azimuth under ideal conditions, essential for hitting targets within 10-50 ft in complex reservoirs.[54] Logging-while-drilling (LWD) tools, often collocated with MWD, acquire formation properties like resistivity and porosity during drilling, reducing non-productive time compared to wireline logging.[48] Drill bits for directional drilling prioritize side-cutting aggression and durability, with polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) bits dominating horizontal sections for their shear efficiency in shales, achieving footage rates over 100 ft/hr in unconventional plays.[55] Drilling fluids, engineered with viscosifiers and lubricants, stabilize the borehole, power mud motors, and transmit MWD signals, with densities adjusted to 8-12 ppg to counter formation pressures.[47] Surface equipment includes top-drive rigs with automated pipe handling, capable of torques up to 50,000 ft-lb for handling extended laterals over 2 miles.[52]Applications

Oil and Gas Extraction

, where wellbores extend several miles laterally from offshore platforms to distant fields, reducing the need for additional subsea infrastructure.[1] Multilateral drilling branches the well into multiple paths from a single borehole to drain complex reservoirs, and short-radius drilling allows sharp turns for precise targeting in mature fields.[1] Combined with hydraulic fracturing, horizontal directional drilling has been pivotal in the U.S. shale revolution, enabling extraction from tight formations previously uneconomical with vertical wells.[7] For instance, horizontal sections can extend up to 10,000 feet, increasing production rates by exposing more reservoir surface area compared to vertical bores.[57] The adoption of directional drilling has significantly boosted extraction efficiency and output. In the U.S., shale oil production surged by over 7 million barrels per day from 2010 to 2019, driven largely by advancements in horizontal drilling techniques that improved reservoir drainage and recovery factors.[25] This method also allows multiple wells to be drilled from a single surface pad, minimizing land disturbance and infrastructure costs while accessing clustered reservoirs.[57] Overall, it enhances economic viability by targeting bypassed hydrocarbons and optimizing well paths based on seismic data, though success depends on accurate geosteering to maintain trajectory within productive zones.[16]Utility and Pipeline Installation

Horizontal directional drilling (HDD), a trenchless variant of directional drilling, enables the installation of underground pipelines and utilities such as water lines, sewer conduits, gas mains, electric cables, and fiber optic networks beneath obstacles including roadways, rivers, and railways without extensive surface excavation.[58][59] This method minimizes disruption to traffic, landscapes, and existing infrastructure, making it suitable for urban and environmentally sensitive areas.[60] The HDD process begins with drilling a small-diameter pilot hole along a predetermined curved trajectory using a steerable drill head guided by surface tracking systems for real-time adjustments.[61][60] The hole is then enlarged through successive reaming passes with progressively larger cutting tools to accommodate the product pipe diameter, followed by the pullback phase where the pipeline or utility conduit is attached to the drill string and pulled into the bored path while simultaneously circulating drilling fluid to stabilize the borehole and remove cuttings.[61][60] Drilling fluids, typically bentonite-based muds, aid in borehole stability and cuttings evacuation but require careful management to prevent inadvertent returns or frac-outs that could impact groundwater.[61] HDD supports installations of pipes up to 60 inches in diameter over distances exceeding 15,000 feet, particularly effective for crossing waterways and congested utility corridors.[59] In pipeline applications, it facilitates the placement of oil, gas, and product lines under barriers, with surveys indicating approximately 53% of HDD usage dedicated to such pipeline projects alongside 70% for general underground utilities.[62] The technique's adoption has driven market growth, with the global HDD sector valued at USD 7.93 billion in 2023 and projected to reach USD 19.15 billion by 2030, reflecting increasing demand for efficient infrastructure upgrades.[63] Pre-installation utility locates and geotechnical assessments are critical to mitigate risks of striking existing lines or encountering unstable soils.[64]Advantages

Economic and Operational Benefits

Directional drilling facilitates multi-well pad development, allowing multiple wells to be drilled from a single surface location, which minimizes the number of pads, access roads, and production facilities required.[65][66] This approach leverages economies of scale, shared infrastructure, and reduced rig mobilization times, lowering overall field development costs.[67][68] In the Permian Basin, such techniques have enabled drilling approximately 46 million feet with fewer than 300 rigs in 2021, compared to under 20 million feet with around 300 rigs in 2014.[69] Operationally, directional drilling enhances efficiency by increasing well footage per completion; in the U.S., average footage per well rose from 7,300 feet in 2010 to 15,200 feet in 2021, doubling productivity for crude oil while total drilled footage declined by 30%.[70] Longer laterals, such as 2-mile sections in the Midland Basin, reduce drilling times by nearly 30% to about 10 days per well.[69] Completion efficiencies further improve with methods like simul-fracs, which cut times by around 70% relative to traditional designs.[69] These advancements support higher initial production rates, with average Permian well productivity increasing from 850 to 1,000 BOE/D between 2019 and 2022.[69] Economically, the technique yields 15-20% reductions in drilling and completion costs for extended laterals like 15,000 feet, offsetting higher per-well upfront expenses through superior reservoir contact and recovery.[69] By 2021, horizontal and directional wells comprised 81% of U.S. completions, underscoring their role in enabling sustained production growth amid declining rig counts and footage.[70] In applications beyond oil and gas, such as utility installations, directional methods decrease surface restoration expenses and disruption by avoiding extensive trenching.[8]

Environmental and Land-Use Advantages

Directional drilling substantially reduces the surface footprint required for resource extraction by enabling multiple horizontal wellbores to be drilled from a single pad site, in contrast to vertical drilling which necessitates separate locations for each well. This approach can consolidate up to 90% fewer surface sites, minimizing the need for extensive access roads, pads, and support infrastructure.[71] In shale plays, such as the Marcellus Formation, this consolidation has allowed operators to access thousands of acres of reservoir from pads covering mere acres, thereby limiting soil compaction and vegetation removal. The technique preserves land use by avoiding direct surface penetration in fragmented or ecologically sensitive terrains, permitting well trajectories to navigate beneath obstacles like rivers, wetlands, or protected habitats without altering topography or introducing erosion risks. Horizontal directional drilling (HDD) methods, an extension of directional principles, have demonstrated this in utility installations crossing waterways, where subsurface paths reduce collateral damage to aquatic ecosystems compared to open-cut trenching.[72] Empirical assessments indicate that HDD lowers land management disturbances by factors of 5-10 times relative to traditional excavation, as subsurface operations eliminate widespread topsoil disturbance and facilitate site restoration post-drilling.[72] Environmentally, the diminished surface activity correlates with reduced fugitive emissions and energy inputs, as fewer rig setups and mobilizations cut fuel consumption during operations. Studies quantify that advanced directional technologies, including multilateral completions, decrease overall construction energy use by optimizing rig time and minimizing ancillary equipment deployment. Additionally, by concentrating activities, directional drilling limits habitat fragmentation—a key driver of biodiversity loss—allowing continuous landscapes to remain intact while enabling resource recovery, as evidenced in applications traversing urban or agricultural parcels without subdividing ownership or disrupting farming operations.[73] This targeted access also mitigates risks of surface spills or leaks propagating into groundwater, as entry points are centralized and more readily monitored.[72]Disadvantages and Challenges

Technical and Operational Limitations

One primary technical limitation in directional drilling is the increased torque and drag experienced by the drill string as wellbore deviation grows, which restricts the transmission of weight on bit and rotational torque, potentially halting progress before reaching the target depth. In extended-reach drilling (ERD), these frictional forces can limit horizontal displacements to ratios exceeding 2:1 relative to vertical depth, with maximum measured depths typically constrained to around 12,000 meters due to buckling risks and rig equipment capacities.[74][75] This issue is exacerbated in highly deviated sections, where contact forces between the string and borehole wall amplify drag, necessitating trajectory optimizations like catenary profiles to mitigate friction.[76] Hole cleaning poses another operational challenge, particularly in wells inclined beyond 67 degrees, where cuttings tend to settle on the low side of the borehole, forming beds that impede fluid circulation and increase the risk of stuck pipe or pack-off. Effective removal requires elevated annular velocities and optimized drilling fluids, but insufficient flow rates—often limited by pump capacities or equivalent circulating density concerns—can lead to non-productive time exceeding 20% in severe cases.[77][78] In horizontal sections, this limitation compounds with reduced gravitational assistance for cuttings transport, demanding specialized sweeps or rotary agitation to maintain borehole integrity.[79] Precision in trajectory control is constrained by dogleg severity (DLS) capabilities, typically limited to 8–17 degrees per 100 feet in build sections to avoid excessive stresses on bottomhole assemblies, casing, and logging tools. High DLS demands responsive steering systems, but formation heterogeneity, bit walk, and toolface orientation errors can result in tortuosity, deviating the wellbore from planned paths by several meters.[80][1] Operational surveys via measurement-while-drilling tools provide real-time data, yet magnetic interference or sensor limitations in complex geology reduce positional accuracy to within 1–2% of measured depth.[81] Geotechnical factors further limit feasibility, as unstable formations like shales or unconsolidated sands promote wellbore collapse, lost circulation, or inadvertent returns in horizontal directional drilling variants. In oil and gas applications, alternating shale-sand sequences heighten instability risks, often requiring reactive mud systems that elevate costs and environmental exposure.[82] Vibrational modes from aggressive drilling amplify equipment fatigue, with downhole tools susceptible to failure rates increasing by factors of 2–5 in deviated wells compared to vertical ones.[83] These constraints collectively elevate non-productive time, with industry data indicating directional wells experience 10–30% higher downtime from such issues than vertical counterparts.[78]Cost and Risk Factors

Directional drilling incurs higher upfront costs compared to conventional vertical drilling, primarily due to the need for specialized bottom-hole assemblies (BHAs), measurement-while-drilling (MWD) tools, and rotary steerable systems, which can increase expenses by a factor of 2 to 3.[84][14] For a modern horizontal well in oil and gas extraction, drilling-phase costs alone often exceed $4 million, driven by extended rig time, complex tool rentals, and requirements for highly skilled directional drillers whose day rates can surpass $1,000 per hour.[85] These elevated capital expenditures are compounded by operational challenges, such as longer drilling durations—typically 20-50% more time than vertical wells—leading to higher non-productive time (NPT) from issues like torque-and-drag management or hole cleaning in deviated sections.[86] Financial risks arise from the potential for inconsistent performance, which has historically cost the oil and gas industry billions in overruns, missed targets, and suboptimal reservoir contact.[87] Trajectory deviations or tool failures can necessitate sidetracks, adding 10-30% to total well costs, while market volatility in commodity prices amplifies exposure, as breakeven thresholds for horizontal wells often require oil prices above $40-50 per barrel to justify the investment.[88] In utility applications, such as pipeline installation, costs range from $25 to $50 per linear foot, escalating in challenging terrains like hard rock or unstable soils, where unplanned interventions can double budgets.[89] Key operational risks include borehole instability, stuck pipe, and inadvertent returns (frac-outs) of drilling fluids, which pose environmental hazards through soil and groundwater contamination if containment fails.[90] Safety concerns encompass machinery failures, high-pressure fluid handling, and worker exposure to noise exceeding 85 dB or confined-space entry during reaming, with historical incident rates for horizontal directional drilling (HDD) operations showing elevated potential for equipment tip-overs or line strikes.[91][92] Cross bores with existing utilities represent a subsurface risk, potentially leading to gas leaks or explosions if undetected, underscoring the need for pre-drill geophysical surveys to mitigate failure probabilities estimated at 5-15% in complex geologies.[93] Overall, while directional drilling's precision reduces surface disturbances, its technical demands heighten the likelihood of costly downtime, with NPT accounting for up to 20-40% of total drilling time in deviated wells.[94]Legal and Regulatory Aspects

Trespass and Resource Drainage Disputes

Directional drilling, particularly horizontal techniques, allows wellbores to cross subsurface property boundaries, raising disputes over trespass when operators access formations beneath unleased lands without consent.[95] Subsurface trespass occurs through physical invasion, such as the wellbore or hydraulic fractures extending into adjacent mineral estates, distinct from mere drainage where hydrocarbons migrate naturally.[96] Courts have ruled that intentional directional deviations creating direct intrusions constitute actionable trespass, rejecting claims of incidental crossings as defenses.[96] The rule of capture, a common law doctrine, permits landowners to extract oil and gas from beneath their surface without liability for draining neighboring reserves, provided no physical trespass invades the adjacent property.[97] This rule applies to hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling where production relies on reservoir migration rather than direct extraction from off-lease areas, as affirmed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in Briggs v. Southwestern Energy Production Co. (2019), which held that artificial stimulation does not negate capture protections absent boundary crossing.[98] However, when wellbores or fractures demonstrably trespass, the rule offers no shield, enabling claims for damages or injunctions, as in Texas where courts distinguish tight shale formations with minimal cross-tract drainage from conventional reservoirs.[99] Landmark cases illustrate evolving jurisprudence. In Lightning Oil Co. v. Anadarko E&P Onshore, LLC (Tex. App. 2016, affirmed 2017), the court determined that a mineral lease authorizes drilling only for extraction from leased formations, not mere traversal through unleased mineral-bearing zones to reach others, deeming such passage a trespass.[100] Similarly, Pennsylvania's Superior Court in Stone v. Antero Resources Corp. (2020) rejected rule of capture defenses in subsurface trespass suits, holding operators liable for removing shale hydrocarbons directly from beneath unleased properties via invasive well paths.[101] These rulings underscore that operators bear the burden to prove no trespass through geophysical evidence, such as microseismic data showing fracture containment, amid disputes in plays like the Marcellus Shale where horizontal laterals span thousands of feet.[102] Resource drainage claims often intersect with trespass allegations, but courts limit liability under capture doctrines unless plaintiffs demonstrate substantial depletion attributable to off-lease invasions, as in Murphy Exploration & Production Co. v. Adams (Tex. 2018), where the Supreme Court noted horizontal bores in low-permeability shales cause negligible drainage, obviating offset drilling mandates.[99] Regulatory bodies, like the Texas Railroad Commission, may deny forced pooling if drainage evidence is speculative, prioritizing verifiable production impacts over hypothetical losses.[103] Disputes persist due to technological precision limits, with survey errors or unintended deviations fueling litigation, though geophysical modeling and real-time steering mitigate risks in modern operations.[95]Environmental Regulations and Compliance

Directional drilling operations, whether for oil and gas extraction or utility and pipeline installation, are subject to federal and state environmental regulations primarily aimed at preventing groundwater contamination, surface water pollution, and habitat disruption. In the United States, the Clean Water Act (CWA) governs discharges of drilling fluids and requires National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits for any releases into waters of the U.S., including inadvertent returns of bentonite-based drilling mud during horizontal directional drilling (HDD). These returns, if unmanaged, can smother aquatic organisms and alter sediment dynamics in sensitive areas like wetlands or rivers.[104] For oil and gas applications, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) enforce 30 CFR Part 250, Subpart D, mandating that drilling protect natural resources, including conducting operations to avoid harm to aquatic life and requiring directional surveys to ensure well integrity.[105] On federal lands, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) policies encourage multi-well pads with directional drilling to minimize surface disturbance, thereby reducing cumulative impacts like soil erosion and habitat fragmentation, as clarified in 2018 guidance.[106] Hydraulic fracturing associated with horizontal wells benefits from exemptions under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) via the 2005 Energy Policy Act, which excludes fracturing fluids from underground injection control regulations unless diesel is used, shifting oversight largely to states. In utility and pipeline HDD projects, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) requires contingency plans for inadvertent returns, including real-time monitoring of drilling fluid pressure, groundwater sampling, and immediate response protocols to contain releases, as outlined in 2019 guidance developed under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).[107] State-level requirements, such as Ohio's HDD Contingency Plan Guidance, mandate pre-construction hydrogeological assessments and post-bore remediation if returns exceed thresholds, emphasizing compliance with wetland protections under Section 404 of the CWA.[108] Drilling fluid disposal must adhere to Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) standards for non-hazardous waste, with contractors documenting minimal soil releases as compliant if below regulatory action levels.[61] Compliance challenges include variable soil permeability leading to frac-outs, which occurred in approximately 5-10% of HDD crossings in some pipeline projects, necessitating mitigation like vacuum trucks for recovery and bioremediation.[109] NEPA reviews for federally permitted projects assess alternatives to open-cut methods, often favoring HDD for reduced erosion—studies show it disturbs up to 90% less surface area than trenching—though regulators scrutinize cumulative effects in high-density areas.[106] Violations can result in fines, such as EPA penalties under the CWA for unpermitted discharges exceeding $50,000 per day, underscoring the need for site-specific environmental impact statements. Overall, these frameworks prioritize risk-based mitigation, with directional drilling's subsurface focus enabling lower emissions and land-use impacts compared to vertical or surface-intensive alternatives when executed under strict protocols.[105]Recent Advancements

Technological Innovations

Advancements in rotary steerable systems (RSS) have enabled more precise control and extended drilling runs in challenging formations. In 2024, innovations such as automated well trajectory control and simplified components allowed RSS to achieve longer bit runs by optimizing rates of penetration and reducing vibrations, pushing boundaries in extended-reach drilling.[110] A 2025 review highlighted RSS evolution toward continuous rotation and smoother boreholes, essential for unconventional resource extraction in regions like China.[111] Integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation has transformed directional drilling by enabling autonomous trajectory adjustments and real-time decision-making. Halliburton demonstrated the first fully AI-driven horizontal well in an unspecified location, where machine learning algorithms analyzed bottomhole assembly tendencies, autonomously drilling 87.4% of the footage and improving reaction times.[112] Schlumberger's 2024 Neuro autonomous platform incorporates cloud and edge AI for geosteering, selecting optimal paths based on high-fidelity subsurface data to minimize tortuosity and enhance reservoir contact.[113] Similarly, a 2025 collaboration between Nabors and eDrilling leverages AI for enhanced performance, reliability, and efficiency in directional operations.[114] Measurement-while-drilling (MWD) and logging-while-drilling (LWD) technologies have advanced with improved signal transmission and data integration for real-time formation evaluation. Schlumberger's SlimPulse MWD system, updated as of 2022, provides continuous directional surveys and drilling optimization, reducing non-productive time through resilient mud-pulse telemetry.[115] These enhancements support AI-driven systems by delivering high-quality downhole data, enabling predictive modeling of lithology changes and geomechanical risks during directional paths. Digitalization and automation in drilling engineering, including AI-processed datasets, have further reduced human intervention while improving accuracy. Case studies from 2025 indicate that AI-enabled platforms analyze cloud-stored well data to monitor and automate directional control, achieving efficiencies in complex reservoirs.[116] Such innovations collectively lower operational risks and costs, with rotary steerable markets projected to grow at a 7% CAGR through 2030 due to these capabilities.[117]Industry Trends and Future Prospects

The directional drilling services market is projected to expand from USD 17.57 billion in 2025 to USD 25.05 billion by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 7.3%, driven primarily by sustained demand in onshore shale plays and increasing offshore exploration activities.[118] This growth aligns with broader energy sector dynamics, including the recovery of global oil demand and investments in unconventional resources, where directional techniques enable access to reserves inaccessible via vertical drilling.[119] In parallel, the horizontal directional drilling (HDD) segment, used extensively in utility installations and telecommunications, is anticipated to grow from USD 7.93 billion in 2023 to USD 19.15 billion by 2030, fueled by infrastructure expansions such as fiber optic networks and renewable energy projects.[63] Emerging trends emphasize automation and digital integration to enhance precision and efficiency. Industry reports highlight the adoption of AI-driven real-time trajectory optimization and advanced sensors, which have demonstrated potential for 28% faster drilling rates by minimizing deviations and improving bottom-hole assembly (BHA) performance.[120] Automated rod handling systems and telematics-enabled rigs, as seen in recent equipment releases from manufacturers like Ditch Witch and Vermeer, reduce operational downtime and labor requirements, addressing skilled workforce shortages in mature markets.[121] In oilfield applications, fully autonomous drilling systems—capable of self-steering across well sections—are advancing toward commercial viability, with prototypes from service providers like Schlumberger enabling consistent wellbore placement without continuous human intervention.[122] Future prospects hinge on technological convergence with sustainability imperatives. Enhanced materials, such as titanium drill collars for extended reach, and innovations like U-turn well profiles promise to unlock complex reservoirs while reducing environmental footprints through minimized surface disturbance.[123] Applications are expanding beyond hydrocarbons into geothermal energy extraction and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) projects, where precise subsurface targeting is critical for viability.[124] However, realization of these prospects depends on overcoming volatility in commodity prices and regulatory hurdles, with North American markets—projected to reach USD 14.5 billion by 2025—serving as a bellwether for global adoption amid shale production plateaus.[125] Overall, directional drilling's evolution toward data-centric, autonomous operations positions it as a cornerstone for resource-efficient energy development through 2035.[119]References

- https://wiki.seg.org/wiki/Measurement-while-drilling