Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

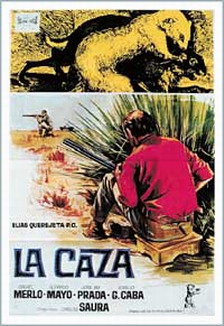

The Hunt (1966 film)

View on Wikipedia| The Hunt | |

|---|---|

Spanish film poster | |

| Directed by | Carlos Saura |

| Written by | Angelino Fons Carlos Saura |

| Produced by | Elías Querejeta |

| Starring | Ismael Merlo Alfredo Mayo José María Prada Emilio Gutiérrez Caba |

| Cinematography | Luis Cuadrado |

| Edited by | Pablo González del Amo |

| Music by | Luis de Pablo |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | Spain |

| Language | Spanish |

The Hunt (in Spanish La Caza) is a 1966 Spanish psychological thriller film directed by Carlos Saura, who co-wrote the screenplay with Angelino Fons. The film stars Ismael Merlo, Alfredo Mayo and José María Prada as three Spanish Civil War veterans who meet to go rabbit hunting. It was Saura's first international success, winning the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 16th Berlin International Film Festival. It is considered a classic of Spanish Cinema, and Sam Peckinpah has said that it was a major influence upon him.[1]

Plot

[edit]José, Paco and Luis, three middle-aged men, veteran Falangists, reunite in a provincial village of Castile, spending a hot summer's day drinking, reminiscing and hunting rabbits. José instigates the hunt. He is in debt because of an impending divorce and is living beyond his means with a younger woman. His main objective at the reunion is to secure a loan from Paco, a shrewd businessman, also unhappily in love and looking for younger women. Paco brings with him Luis, now employed at his factory. Luis is a weak, forlorn individual, an alcoholic addicted to wine, women and science fiction rather than social conviviality or male camaraderie. A fourth member of the group, Enrique, a teenage relative of Paco's, comes along for the thrill of the rabbit hunt.

Meeting at the local bar, the men proceed to a run-down farm house and hire Juan and his young niece Carmen to aid them in the hunt, as well as several ferrets to rout the rabbits from their holes. As the hunters prepare their guns, they reminisce about the Civil War and the excitement of hunting men instead of animals. After a few drinks, José asks Paco for a loan; it will cement their relationship, he says. Paco, who has grudgingly been expecting this, refuses, but instead offers José a job.

During the hunt, the men kill several rabbits and eventually lunch on them. Their relationships become more estranged as they fret over the past and rebuke each other in several ways. Luis becomes deranged and turns to practice-shooting with a mannequin; he also starts a fire that grows too large and has to be put out. Near the end, Paco kills a ferret; he claims he shot it accidentally, but José feels he did it maliciously. As the hunt gains in intensity, the gunfire becomes more rapid. The smoldering hatred and frustrations of the three men are triggered when Paco is hit by a blast from José's shotgun and falls mortally wounded, into a stream. Luis, enraged by the killing, tries to kill José by running him down with a land rover. José retaliates, shooting at Luis, but the latter manages to survive long enough to shoot at the escaping José and kill him before going down himself. Enrique, unhurt, is left alone in the midst of this carnage, trying to fathom the inexplicable behavior of the three wartime comrades. The movie ends in a freeze-frame as he runs away from the carnage.

Cast

[edit]- Ismael Merlo as José

- Alfredo Mayo as Paco

- José María Prada as Luis

- Emilio Gutiérrez Caba as Enrique (credited as Emilio G. Caba)

- Fernando Sánchez Polack as Juan

- Violeta García as Carmen

- María Sánchez Aroca as La Madre de Juan

Reception

[edit]The film was shot in a valley that once witnessed a Civil War battle similar to the one described in the dialogue. Saura won the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 16th Berlin International Film Festival in 1966.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Kinder, Marsha (2001). "the Cultural Reinscription of The Wild Bunch" (PDF). In Slocum, John David (ed.). Violence and American Cinema (PDF). Psychology Press. pp. 64–100. ISBN 9780415928106. ISSN 2577-7610. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Berlinale 1966: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

Notes

[edit]- D'Lugo, Marvin, The Films of Carlos Saura, Princeton University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-691-03142-8

- Schwartz, Ronald, The Great Spanish Films: 1950- 1990, Scarecrow Press, London, 1991, ISBN 0-8108-2488-4

External links

[edit]- La caza at IMDb

- La caza, Carlos Saura y el nuevo cine español Suite101 (Spanish)

The Hunt (1966 film)

View on GrokipediaLa caza (English: The Hunt) is a 1966 Spanish psychological thriller written and directed by Carlos Saura, centering on three middle-aged men—veterans of the Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War—who reunite for a rabbit hunt in rural Castile, where simmering personal and ideological tensions erupt into violence.[1][2]

The film, Saura's third feature, marked a breakthrough in his career, earning him the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 16th Berlin International Film Festival and establishing his reputation for probing the psychological scars of Francoist Spain under strict censorship.[3][4]

Critically acclaimed for its tense atmosphere and allegorical depth, La caza portrays the hunt as a microcosm of civil strife, with the characters' deteriorating camaraderie reflecting broader authoritarian repression and unresolved postwar divisions, though its overt critique of the regime's brutality evaded full suppression at the time.[1][5][6]

Produced amid the regime's controls, the film's unflinching examination of masculinity, aging, and latent aggression has since been hailed as a cornerstone of New Spanish Cinema, influencing interpretations of Franco-era society through motifs like myxomatosis-afflicted rabbits symbolizing national decay.[7][8]