Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Renaissance

View on Wikipedia

| Renaissance |

|---|

|

| Aspects |

| Regions |

| History and study |

The Renaissance (UK: /rɪˈneɪsəns/ rin-AY-sənss, US: /ˈrɛnəsɑːns/ ⓘ REN-ə-sahnss)[1][2][a] is a period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and surpass the ideas and achievements of classical antiquity. Associated with great social change in most fields and disciplines, including art, architecture, politics, literature, exploration and science, the Renaissance was first centered in the Republic of Florence, then spread to the rest of Italy and later throughout Europe. The term rinascita ("rebirth") first appeared in Lives of the Artists (c. 1550) by Giorgio Vasari, while the corresponding French word renaissance was adopted into English as the term for this period during the 1830s.[4][b]

The Renaissance's intellectual basis was founded in its version of humanism, derived from the concept of Roman humanitas and the rediscovery of classical Greek philosophy, such as that of Protagoras, who said that "man is the measure of all things". Although the invention of metal movable type sped the dissemination of ideas from the later 15th century, the changes of the Renaissance were not uniform across Europe: the first traces appear in Italy as early as the late 13th century, in particular with the writings of Dante and the paintings of Giotto.

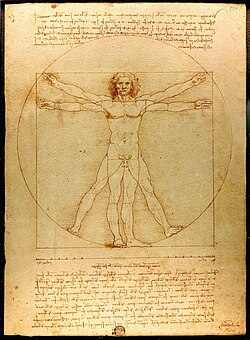

As a cultural movement, the Renaissance encompassed innovative flowering of literary Latin and an explosion of vernacular literatures, beginning with the 14th-century resurgence of learning based on classical sources, which contemporaries credited to Petrarch; the development of linear perspective and other techniques of rendering a more natural reality in painting; and gradual but widespread educational reform. It saw myriad artistic developments and contributions from such polymaths as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who inspired the term "Renaissance man".[5][6] In politics, the Renaissance contributed to the development of the customs and conventions of diplomacy, and in science to an increased reliance on observation and inductive reasoning. The period also saw revolutions in other intellectual and social scientific pursuits, as well as the introduction of modern banking and the field of accounting.[7]

Period

[edit]The Renaissance period started during the crisis of the Late Middle Ages and conventionally ends with the waning of humanism, and the advents of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, and in art, the Baroque period. It had a different period and characteristics in different regions, such as the Italian Renaissance, the Northern Renaissance, the Spanish Renaissance, etc.

In addition to the standard periodization, proponents of a "long Renaissance" may put its beginning in the 14th century and its end in the 17th century.[c]

The traditional view focuses more on the Renaissance's early modern aspects and argues that it was a break from the past, but many historians today focus more on its medieval aspects and argue that it was an extension of the Middle Ages.[11][12]

Italian Renaissance

[edit]The beginnings of the period—the early Renaissance of the 15th century and the Italian Proto-Renaissance from around 1250 or 1300—overlap considerably with the Late Middle Ages, conventionally dated to c. 1350–1500, and the Middle Ages themselves were a long period filled with gradual changes, like the modern age; as a transitional period between both, the Renaissance has close similarities to both, especially the late and early sub-periods of either.

The Renaissance began in Florence, one of the many states of Italy.[13] The Italian Renaissance concluded in 1527 when Holy Roman Emperor Charles V launched an assault on Rome during the war of the League of Cognac. Nevertheless, its impact endured in the art of renowned Italian painters like Tintoretto, Sofonisba Anguissola, and Paolo Veronese, who continued their work during the mid-to-late 16th century.[14]

Various theories have been proposed to account for its origins and characteristics, focusing on a variety of factors, including Florence's social and civic peculiarities at the time: its political structure, the patronage of its dominant family, the Medici,[15] and the migration of Greek scholars and their texts to Italy following the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire.[16][17][18] Other major centers were Venice, Genoa, Milan, Rome during the Renaissance Papacy, and Naples. From Italy, the Renaissance spread throughout Europe and also to American, African and Asian territories ruled by the European colonial powers of the time or where Christian missionaries were active.

The Renaissance has a long and complex historiography, and in line with general skepticism of discrete periodizations, there has been much debate among historians reacting to the 19th-century glorification of the "Renaissance" and individual cultural heroes as "Renaissance men", questioning the usefulness of Renaissance as a term and as a historical delineation.[19]

Some observers have questioned whether the Renaissance was a cultural "advance" from the Middle Ages, instead seeing it as a period of pessimism and nostalgia for classical antiquity,[20] while social and economic historians, especially of the longue durée, have instead focused on the continuity between the two eras,[21] which are linked, as Panofsky observed, "by a thousand ties".[22][d]

The word has also been extended to other historical and cultural movements, such as the Carolingian Renaissance (8th and 9th centuries), Ottonian Renaissance (10th and 11th century), and the Renaissance of the 12th century.[24]

Overview

[edit]The Renaissance was a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life in the early modern period. Beginning in Italy, and spreading to the rest of Europe by the 16th century, its influence was felt in art, architecture, philosophy, literature, music, science, technology, politics, religion, and other aspects of intellectual inquiry. Renaissance scholars employed the humanist method in study, and searched for realism and human emotion in art.[25]

Renaissance humanists such as Poggio Bracciolini sought out in Europe's monastic libraries the Latin literary, historical, and oratorical texts of antiquity, while the fall of Constantinople (1453) generated a wave of émigré Greek scholars bringing precious manuscripts in ancient Greek, many of which had fallen into obscurity in the West. It was in their new focus on literary and historical texts that Renaissance scholars differed so markedly from the medieval scholars of the Renaissance of the 12th century, who had focused on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural sciences, philosophy, and mathematics, rather than on such cultural texts.[citation needed]

In the revival of neoplatonism, Renaissance humanists did not reject Christianity; on the contrary, many of the Renaissance's greatest works were devoted to it, and the Church patronized many works of Renaissance art.[26] But a subtle shift took place in the way that intellectuals approached religion that was reflected in many other areas of cultural life.[27][better source needed] In addition, many Greek Christian works, including the Greek New Testament, were brought back from Byzantium to Western Europe and engaged Western scholars for the first time since late antiquity. This new engagement with Greek Christian works, and particularly the return to the original Greek of the New Testament promoted by humanists Lorenzo Valla and Erasmus, helped pave the way for the Reformation.[citation needed]

Well after the first artistic return to classicism had been exemplified in the sculpture of Nicola Pisano, Florentine painters led by Masaccio strove to portray the human form realistically, developing techniques to render perspective and light more naturally. Political philosophers, most famously Niccolò Machiavelli, sought to describe political life as it really was, that is to understand it rationally. A critical contribution to Italian Renaissance humanism, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola wrote De hominis dignitate (Oration on the Dignity of Man, 1486), a series of theses on philosophy, natural thought, faith, and magic defended against any opponent on the grounds of reason. In addition to studying classical Latin and Greek, Renaissance authors also began increasingly to use vernacular languages; combined with the introduction of the printing press, this allowed many more people access to books, especially the Bible.[28]

In all, the Renaissance can be viewed as an attempt by intellectuals to study and improve the secular and worldly, both through the revival of ideas from antiquity and through novel approaches to thought. Political philosopher Hans Kohn describes it as an age where "Men looked for new foundations"; some like Erasmus and Thomas More envisioned new reformed spiritual foundations, others. in the words of Machiavelli, una lunga sperienza delle cose moderne ed una continua lezione delle antiche (a long experience with modern life and a continuous learning from antiquity).[29]

Sociologist Rodney Stark plays down the Renaissance in favor of the earlier innovations of the Italian city-states in the High Middle Ages, which married responsive government, Christianity and the birth of capitalism.[30] This analysis argues that, whereas the great European states (France and Spain) were absolute monarchies, and others were under direct Church control, the independent city-republics of Italy took over the principles of capitalism invented on monastic estates and set off a vast unprecedented Commercial Revolution that preceded and financed the Renaissance.[citation needed]

Historian Leon Poliakov offers a critical view in his seminal study of European racist thought: The Aryan Myth. According to Poliakov, the use of ethnic origin myths are first used by Renaissance humanists "in the service of a new born chauvinism".[31][32]

Origins

[edit]

Many argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in Florence at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, in particular with the writings of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Petrarch (1304–1374), as well as the paintings of Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337). Some writers date the Renaissance quite precisely; one proposed starting point is 1401, when the rival geniuses Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi competed for the contract to build the bronze doors for the Baptistery of the Florence Cathedral (Ghiberti won).[33] Others see more general competition between artists and polymaths such as Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, and Masaccio for artistic commissions as sparking the creativity of the Renaissance.

Yet it remains much debated why the Renaissance began in Italy, and why it began when it did. Accordingly, several theories have been put forward to explain its origins. Peter Rietbergen posits that various influential Proto-Renaissance movements started from roughly 1300 onwards across many regions of Europe.[34]

Latin and Greek phases of Renaissance humanism

[edit]

In stark contrast to the High Middle Ages, when Latin scholars focused almost entirely on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural science, philosophy and mathematics,[e] Renaissance scholars were most interested in recovering and studying Latin and Greek literary, historical, and oratorical texts. Broadly speaking, this began in the 14th century with a Latin phase, when Renaissance scholars such as Petrarch, Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364–1437), and Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) scoured the libraries of Europe in search of works by such Latin authors as Cicero, Lucretius, Livy, and Seneca.[35] By the early 15th century, the bulk of the surviving such Latin literature had been recovered; the Greek phase of Renaissance humanism was under way, as Western European scholars turned to recovering ancient Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts.[36]

Unlike with Latin texts, which had been preserved and studied in Western Europe since late antiquity, the study of ancient Greek texts was very limited in medieval Western Europe. Ancient Greek works on science, mathematics, and philosophy had been studied since the High Middle Ages in Western Europe and in the Islamic Golden Age (normally in translation), but Greek literary, oratorical and historical works (such as Homer, the Greek dramatists, Demosthenes and Thucydides) were not studied in either the Latin or medieval Islamic worlds; in the Middle Ages these sorts of texts were only studied by Byzantine scholars. Some argue that the Timurid Renaissance in Samarkand and Herat, whose magnificence toned with Florence as the center of a cultural rebirth,[37][38] were linked to the Ottoman Empire, whose conquests led to the migration of Greek scholars to Italian cities.[16][39] One of the greatest achievements of Renaissance scholars was to bring this entire class of Greek cultural works back into Western Europe for the first time since late antiquity.

Muslim logicians, most notably Avicenna and Averroes, had inherited Greek ideas after they had invaded and conquered Egypt and the Levant. Their translations and commentaries on these ideas worked their way through the Arab West into Iberia and Sicily, which became important centers for this transmission of ideas. Between the 11th and 13th centuries, many schools dedicated to the translation of philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic to Medieval Latin were established in Iberia, most notably the Toledo School of Translators. This work of translation from Islamic culture, though largely unplanned and disorganized, constituted one of the greatest transmissions of ideas in history.[40]

The movement to reintegrate the regular study of Greek literary, historical, oratorical, and theological texts back into the Western European curriculum is usually dated to the 1396 invitation from Coluccio Salutati to the Byzantine diplomat and scholar Manuel Chrysoloras (c. 1355–1415) to teach Greek in Florence.[41] This legacy was continued by a number of expatriate Greek scholars, from Basilios Bessarion to Leo Allatius.

Social and political structures in Italy

[edit]

The unique political structures of Italy during the Late Middle Ages have led some to theorize that its unusual social climate allowed the emergence of a rare cultural efflorescence. Italy did not exist as a political entity in the early modern period. Instead, it was divided into smaller city-states and territories: the Neapolitans controlled the south, the Florentines and the Romans at the center, the Milanese and the Genoese to the north and west respectively, and the Venetians to the north east. 15th-century Italy was one of the most urbanized areas in Europe.[42] Many of its cities stood among the ruins of ancient Roman buildings; it seems likely that the classical nature of the Renaissance was linked to its origin in the Roman Empire's heartland.[43]

Historian and political philosopher Quentin Skinner points out that Otto of Freising (c. 1114–1158), a German bishop visiting north Italy during the 12th century, noticed a widespread new form of political and social organization, observing that Italy appeared to have exited from feudalism so that its society was based on merchants and commerce. Linked to this was anti-monarchical thinking, represented in the famous early Renaissance fresco cycle The Allegory of Good and Bad Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (painted 1338–1340), whose strong message is about the virtues of fairness, justice, republicanism and good administration. Holding both Church and Empire at bay, these city republics were devoted to notions of liberty. Skinner reports that there were many defences of liberty such as the Matteo Palmieri (1406–1475) celebration of Florentine genius not only in art, sculpture and architecture, but "the remarkable efflorescence of moral, social and political philosophy that occurred in Florence at the same time".[44]

Even cities and states beyond central Italy, such as the Republic of Florence at this time, were also notable for their merchant republics, especially the Republic of Venice. Although in practice these were oligarchical, and bore little resemblance to a modern democracy, they did have democratic features and were responsive states, with forms of participation in governance and belief in liberty.[44][45][46] The relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement.[47] Likewise, the position of Italian cities such as Venice as great trading centres made them intellectual crossroads. Merchants brought with them ideas from far corners of the globe, particularly the Levant. Venice was Europe's gateway to trade with the East, and a producer of fine glass, while Florence was a capital of textiles. The wealth such business brought to Italy meant large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned and individuals had more leisure time for study.[47]

Black Death

[edit]

One theory that has been advanced is that the devastation in Florence caused by the Black Death, which hit Europe between 1348 and 1350, resulted in a shift in the world view of people in 14th century Italy. Italy was particularly badly hit by the plague, and it has been speculated that the resulting familiarity with death caused thinkers to dwell more on their lives on Earth, rather than on spirituality and the afterlife.[48] It has also been argued that the Black Death prompted a new wave of piety, manifested in the sponsorship of religious works of art.[49] However, this does not fully explain why the Renaissance occurred specifically in Italy in the 14th century. The Black Death was a pandemic that affected all of Europe in the ways described, not only Italy. The Renaissance's emergence in Italy was most likely the result of the complex interaction of the above factors.[19]

The plague was carried by fleas on sailing vessels returning from the ports of Asia, spreading quickly due to lack of proper sanitation: the population of England, then about 4.2 million, lost 1.4 million people to the bubonic plague. Florence's population was nearly halved in the year 1348. As a result of the decimation in the populace the value of the working class increased, and commoners came to enjoy more freedom. To answer the increased need for labor, workers traveled in search of the most favorable position economically.[50]

The demographic decline due to the plague had economic consequences: the prices of food dropped and land values declined by 30–40% in most parts of Europe between 1350 and 1400.[51] Landholders faced a great loss, but for ordinary men and women it was a windfall. The survivors of the plague found not only that the prices of food were cheaper but also that lands were more abundant, and many of them inherited property from their dead relatives.

The spread of disease was significantly more rampant in areas of poverty. Epidemics ravaged cities, particularly children. Plagues were easily spread by lice, unsanitary drinking water, armies, or by poor sanitation. Children were hit the hardest because many diseases, such as typhus and congenital syphilis, target the immune system, leaving young children without a fighting chance. Children in city dwellings were more affected by the spread of disease than the children of the wealthy.[52]

The Black Death caused greater upheaval to Florence's social and political structure than later epidemics. Despite a significant number of deaths among members of the ruling classes, the government of Florence continued to function during this period. Formal meetings of elected representatives were suspended during the height of the epidemic due to the chaotic conditions in the city, but a small group of officials was appointed to conduct the affairs of the city, which ensured continuity of government.[53]

Cultural conditions in Florence

[edit]

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in Florence, and not elsewhere in Italy. Scholars have noted several features unique to Florentine cultural life that may have caused such a cultural movement. Many have emphasized the role played by the Medici, a banking family and later ducal ruling house, in patronizing and stimulating the arts. Some historians have postulated that Florence was the birthplace of the Renaissance as a result of luck, i.e., because "Great Men" were born there by chance:[54] Leonardo, Botticelli and Michelangelo were all born in Tuscany. Arguing that such chance seems improbable, other historians have contended that these "Great Men" were only able to rise to prominence because of the prevailing cultural conditions at the time.[55]

Lorenzo de' Medici (1449–1492) was the catalyst for an enormous amount of arts patronage, encouraging his countrymen to commission works from the leading artists of Florence, including Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo Buonarroti.[15] Works by Neri di Bicci, Botticelli, Leonardo, and Filippino Lippi had been commissioned additionally by the Convent of San Donato in Scopeto in Florence.[56]

The Renaissance was certainly underway before Lorenzo de' Medici came to power – indeed, before the Medici family itself achieved hegemony in Florentine society.

Characteristics

[edit]Humanism

[edit]In some ways, Renaissance humanism was not a philosophy but a method of learning. In contrast to the medieval scholastic mode, which focused on resolving contradictions between authors, Renaissance humanists would study ancient texts in their original languages and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and empirical evidence. Humanist education was based on the programme of Studia Humanitatis, the study of five humanities: poetry, grammar, history, moral philosophy, and rhetoric. Although historians have sometimes struggled to define humanism precisely, most have settled on "a middle of the road definition... the movement to recover, interpret, and assimilate the language, literature, learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome".[57] Above all, humanists asserted "the genius of man ... the unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind".[58]

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas More revived the ideas of Greek and Roman thinkers and applied them in critiques of contemporary government, following the Islamic steps of Ibn Khaldun.[60][61] Pico della Mirandola wrote the "manifesto" of the Renaissance, the Oration on the Dignity of Man, a vibrant defence of thinking.[citation needed] Matteo Palmieri (1406–1475), another humanist, is most known for his work Della vita civile ("On Civic Life"; printed 1528), which advocated civic humanism, and for his influence in refining the Tuscan vernacular to the same level as Latin. Palmieri drew on Roman philosophers and theorists, especially Cicero, who, like Palmieri, lived an active public life as a citizen and official, as well as a theorist and philosopher and also Quintilian. Perhaps the most succinct expression of his perspective on humanism is in a 1465 poetic work La città di vita, but an earlier work, Della vita civile, is more wide-ranging. Composed as a series of dialogues set in a country house in the Mugello countryside outside Florence during the plague of 1430, Palmieri expounds on the qualities of the ideal citizen. The dialogues include ideas about how children develop mentally and physically, how citizens can conduct themselves morally, how citizens and states can ensure probity in public life, and an important debate on the difference between that which is pragmatically useful and that which is honest.[citation needed]

The humanists believed that it is important to transcend to the afterlife with a perfect mind and body, which could be attained with education. The purpose of humanism was to create a universal man whose person combined intellectual and physical excellence and who was capable of functioning honorably in virtually any situation.[62] This ideology was referred to as the uomo universale, an ancient Greco-Roman ideal. Education during the Renaissance was mainly composed of ancient literature and history as it was thought that the classics provided moral instruction and an intensive understanding of human behavior.

Humanism and libraries

[edit]A unique characteristic of some Renaissance libraries is that they were open to the public. These libraries were places where ideas were exchanged and where scholarship and reading were considered both pleasurable and beneficial to the mind and soul. As freethinking was a hallmark of the age, many libraries contained a wide range of writers. Classical texts could be found alongside humanist writings. These informal associations of intellectuals profoundly influenced Renaissance culture. An essential tool of Renaissance librarianship was the catalog that listed, described, and classified a library's books.[63] Some of the richest "bibliophiles" built libraries as temples to books and knowledge. A number of libraries appeared as manifestations of immense wealth joined with a love of books. In some cases, cultivated library builders were also committed to offering others the opportunity to use their collections. Prominent aristocrats and princes of the Church created great libraries for the use of their courts, called "court libraries", and were housed in lavishly designed monumental buildings decorated with ornate woodwork, and the walls adorned with frescoes (Murray, Stuart A.P.).

Art

[edit]Renaissance art marks a cultural rebirth at the close of the Middle Ages and rise of the Modern world. One of the distinguishing features of Renaissance art was its development of highly realistic linear perspective. Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337) is credited with first treating a painting as a window into space, but it was not until the demonstrations of architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and the subsequent writings of Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) that perspective was formalized as an artistic technique.[64]

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend toward realism in the arts.[65] Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, human anatomy. Underlying these changes in artistic method was a renewed desire to depict the beauty of nature and to unravel the axioms of aesthetics, with the works of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael representing artistic pinnacles that were much imitated by other artists.[66] Other notable artists include Sandro Botticelli, working for the Medici in Florence, Donatello, another Florentine, and Titian in Venice, among others.

In the Low Countries, a particularly vibrant artistic culture developed. The work of Hugo van der Goes and Jan van Eyck was particularly influential on the development of painting in Italy, both technically with the introduction of oil paint and canvas, and stylistically in terms of naturalism in representation. Later, the work of Pieter Brueghel the Elder would inspire artists to depict themes of everyday life.[67]

In architecture, Filippo Brunelleschi was foremost in studying the remains of ancient classical buildings. With rediscovered knowledge from the 1st-century writer Vitruvius and the flourishing discipline of mathematics, Brunelleschi formulated the Renaissance style that emulated and improved on classical forms. His major feat of engineering was building the dome of Florence Cathedral.[68] Another building demonstrating this style is the Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua, built by Alberti. The outstanding architectural work of the High Renaissance was the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica, combining the skills of Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Sangallo and Maderno.

During the Renaissance, architects aimed to use columns, pilasters, and entablatures as an integrated system. The Roman orders types of columns are used: Tuscan and Composite. These can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was in the Old Sacristy (1421–1440) by Brunelleschi.[69] Arches, semi-circular or (in the Mannerist style) segmental, are often used in arcades, supported on piers or columns with capitals. There may be a section of entablature between the capital and the springing of the arch. Alberti was one of the first to use the arch on a monumental. Renaissance vaults do not have ribs; they are semi-circular or segmental and on a square plan, unlike the Gothic vault, which is frequently rectangular.

Renaissance artists were not pagans, although they admired antiquity and kept some ideas and symbols of the medieval past. Nicola Pisano (c. 1220 – c. 1278) imitated classical forms by portraying scenes from the Bible. His Annunciation, from the Pisa Baptistry, demonstrates that classical models influenced Italian art before the Renaissance took root as a literary movement.[70]

Science

[edit]

Applied innovation extended to commerce. At the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli published the first work on bookkeeping, making him the founder of accounting.[7]

The rediscovery of ancient texts and the invention of the printing press in about 1440 democratized learning and allowed a faster propagation of more widely distributed ideas. In the first period of the Italian Renaissance, humanists favored the study of humanities over natural philosophy or applied mathematics, and their reverence for classical sources further enshrined the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic views of the universe. Writing around 1450, Nicholas of Cusa anticipated the heliocentric worldview of Copernicus, but in a philosophical fashion.

Science and art were intermingled in the early Renaissance, with polymath artists such as Leonardo da Vinci making observational drawings of anatomy and nature. Leonardo set up controlled experiments in water flow, medical dissection, and systematic study of movement and aerodynamics, and he devised principles of research method that led Fritjof Capra to classify him as the "father of modern science".[g] Other examples of Da Vinci's contribution during this period include machines designed to saw marbles and lift monoliths, and new discoveries in acoustics, botany, geology, anatomy, and mechanics.[73]

A suitable environment had developed to question classical scientific doctrine. The discovery in 1492 of the New World by Christopher Columbus challenged the classical worldview. The works of Ptolemy (in geography) and Galen (in medicine) were found to not always match everyday observations. As the Reformation and Counter-Reformation clashed, the Northern Renaissance showed a decisive shift in focus from Aristotelean natural philosophy to chemistry and the biological sciences (botany, anatomy, and medicine).[74] The willingness to question previously held truths and search for new answers resulted in a period of major scientific advancements.

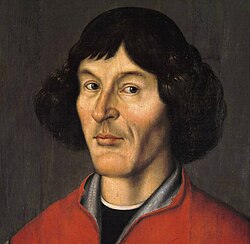

Some view this as a "Scientific Revolution", heralding the beginning of the modern age,[75] others as an acceleration of a continuous process stretching from the ancient world to the present day.[76] Significant scientific advances were made during this time by Galileo Galilei, Tycho Brahe, and Johannes Kepler.[77] Copernicus, in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), posited that the Earth moved around the Sun. De humani corporis fabrica (On the Workings of the Human Body) by Andreas Vesalius, gave a new confidence to the role of dissection, observation, and the mechanistic view of anatomy.[78]

Another important development was in the process for discovery, the scientific method,[78] focusing on empirical evidence and the importance of mathematics, while discarding much of Aristotelian science. Early and influential proponents of these ideas included Copernicus, Galileo, and Francis Bacon.[79][80] The new scientific method led to great contributions in the fields of astronomy, physics, biology, and anatomy.[h][81]

Navigation and geography

[edit]

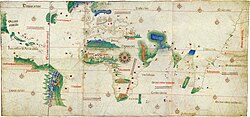

During the Renaissance, extending from 1450 to 1650,[82] every continent was visited and mostly mapped by Europeans, except the south polar continent now known as Antarctica. This development is depicted in the large world map Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula made by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu in 1648 to commemorate the Peace of Westphalia.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain seeking a direct route to India of the Delhi Sultanate. He accidentally stumbled upon the Americas, but believed he had reached the East Indies.

In 1606, the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon sailed from the East Indies in the Dutch East India Company ship Duyfken and landed in Australia. He charted about 300 km of the west coast of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland. More than thirty Dutch expeditions followed, mapping sections of the north, west, and south coasts. In 1642–1643, Abel Tasman circumnavigated the continent, proving that it was not joined to the imagined south polar continent.

By 1650, Dutch cartographers had mapped most of the coastline of the continent, which they named New Holland, except the east coast which was charted in 1770 by James Cook.

The long-imagined south polar continent was eventually sighted in 1820. Throughout the Renaissance it had been known as Terra Australis, or 'Australia' for short. However, after that name was transferred to New Holland in the nineteenth century, the new name of 'Antarctica' was bestowed on the south polar continent.[83]

Music

[edit]From this changing society emerged a common, unifying musical language, in particular the polyphonic style of the Franco-Flemish school. The development of printing made distribution of music possible on a wide scale. Demand for music as entertainment and as an activity for educated amateurs increased with the emergence of a bourgeois class. Dissemination of chansons, motets, and masses throughout Europe coincided with the unification of polyphonic practice into the fluid style that culminated in the second half of the sixteenth century in the work of composers such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Orlande de Lassus, Tomás Luis de Victoria, and William Byrd.

Religion

[edit]

The new ideals of humanism, although more secular in some aspects, developed against a Christian backdrop, especially in the Northern Renaissance. Much, if not most, of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Roman Catholic Church.[27] However, the Renaissance had a profound effect on contemporary theology, particularly in the way people perceived the relationship between man and God.[27] Many of the period's foremost theologians were followers of the humanist method, including Erasmus, Huldrych Zwingli, Thomas More, Martin Luther, and John Calvin.

The Renaissance began in times of religious turmoil. The Late Middle Ages was a period of political intrigue surrounding the Papacy, culminating in the Western Schism, in which three men simultaneously claimed to be true Bishop of Rome.[84] While the schism was resolved by the Council of Constance (1414), a resulting reform movement known as Conciliarism sought to limit the power of the pope. Although the papacy eventually emerged supreme in ecclesiastical matters by the Fifth Council of the Lateran (1511), it was dogged by continued accusations of corruption, most famously in the person of Pope Alexander VI, who was accused variously of simony, nepotism, and fathering children (most of whom were married off, presumably for the consolidation of power) while a cardinal.[85]

Churchmen such as Erasmus and Luther proposed reform to the Church, often based on humanist textual criticism of the New Testament.[27] In October 1517, Luther published the Ninety-five Theses, challenging papal authority and criticizing its perceived corruption, particularly with regard to instances of sold indulgences.[i] The 95 Theses led to the Reformation, a break with the Roman Catholic Church that previously claimed hegemony in Western Europe. Humanism and the Renaissance therefore played a direct role in sparking the Reformation, as well as in many other contemporaneous religious debates and conflicts.

Pope Paul III came to the papal throne (1534–1549) after the sack of Rome in 1527, with uncertainties prevalent in the Catholic Church following the Reformation. Nicolaus Copernicus dedicated De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) to Paul III, who became the grandfather of Alessandro Farnese, who had paintings by Titian, Michelangelo, and Raphael, as well as an important collection of drawings, and who commissioned the masterpiece of Giulio Clovio, arguably the last major illuminated manuscript, the Farnese Hours.

Self-awareness

[edit]

By the 15th century, writers, artists, and architects in Italy were well aware of the transformations that were taking place and were using phrases such as modi antichi (in the antique manner) or alle romana et alla antica (in the manner of the Romans and the ancients) to describe their work. In the 1330s Petrarch referred to pre-Christian times as antiqua (ancient) and to the Christian period as nova (new).[86] From Petrarch's Italian perspective, this new period (which included his own time) was an age of national eclipse.[86] Leonardo Bruni was the first to use tripartite periodization in his History of the Florentine People (1442).[87] Bruni's first two periods were based on those of Petrarch, but he added a third period because he believed that Italy was no longer in a state of decline. Flavio Biondo used a similar framework in Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire (1439–1453).

Humanist historians argued that contemporary scholarship restored direct links to the classical period, thus bypassing the Medieval period, which they then named for the first time the "Middle Ages". The term first appears in Latin in 1469 as media tempestas (middle times).[88] The term rinascita (rebirth) first appeared, however, in its broad sense in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists, 1550, revised 1568.[89][90] Vasari divides the age into three phases: the first phase contains Cimabue, Giotto, and Arnolfo di Cambio; the second phase contains Masaccio, Brunelleschi, and Donatello; the third centers on Leonardo da Vinci and culminates with Michelangelo. It was not just the growing awareness of classical antiquity that drove this development, according to Vasari, but also the growing desire to study and imitate nature.[91]

Spread

[edit]In the 15th century, the Renaissance spread rapidly from its birthplace in Florence to the rest of Italy and soon to the rest of Europe. The invention of the printing press by German printer Johannes Gutenberg allowed the rapid transmission of these new ideas. As it spread, its ideas diversified and changed, being adapted to local culture. In the 20th century, scholars began to break the Renaissance into regional and national movements.

England

[edit]

The Elizabethan era in the second half of the 16th century is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance. Many scholars see its beginnings in the early 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII.[92]

The English Renaissance is different from the Italian Renaissance in several ways. The dominant art forms of the English Renaissance were literature and music, which had a rich flowering.[93] Visual arts in the English Renaissance were much less significant than in the Italian Renaissance. The English Renaissance period in art began far later than the Italian, which had moved into Mannerism by the 1530s.[94]

In literature the later part of the 16th century saw the flowering of Elizabethan literature, with poetry heavily influenced by Italian Renaissance literature but Elizabethan theatre a distinctive native style. Writers include William Shakespeare (1564–1616), Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593), Edmund Spenser (1552–1599), Sir Thomas More (1478–1535), and Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586). English Renaissance music competed with that in Europe with composers such as Thomas Tallis (1505–1585), John Taverner (1490–1545), and William Byrd (1540–1623). Elizabethan architecture produced the large prodigy houses of courtiers, and in the next century Inigo Jones (1573–1652), who introduced Palladian architecture to England.[95]

Elsewhere, Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was the pioneer of modern scientific thought, and is commonly regarded as one of the founders of the Scientific Revolution.[96][97]

France

[edit]

The word "Renaissance" is borrowed from the French language, where it means "re-birth". It was first used in the eighteenth century and was later popularized by French historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874) in his 1855 work, Histoire de France (History of France).[98][99]

In 1495 the Italian Renaissance arrived in France, imported by King Charles VIII after his invasion of Italy. A factor that promoted the spread of secularism was the inability of the Church to offer assistance against the Black Death. Francis I imported Italian art and artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, Primaticcio, Rosso Fiorentino, Niccolò dell'Abbate and Benvenuto Cellini and built ornate palaces at great expense, like the Palace of Fontainebleau and the castle of Chambord. Writers such as François Rabelais, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay, and Michel de Montaigne, painters such as Jean Clouet and François Clouet, and musicians such as Jean Mouton also borrowed from the spirit of the Renaissance. French Renaissance sculptors include Michel Colombe, Jean Goujon, Pierre Bontemps, Ligier Richier and Germain Pilon while important architects of the time were Pierre Lescot, who built the Henri II aisle of the Louvre, Philibert Delorme and Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau.

In 1533, a fourteen-year-old Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589), born in Florence to Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino and Madeleine de La Tour d'Auvergne, married Henry II of France, second son of King Francis I and Queen Claude. Though she became famous and infamous for her role in the French Wars of Religion, she made a direct contribution in bringing arts, sciences, and music (including the origins of ballet) to the French court from her native Florence.

Germany

[edit]

In the second half of the 15th century, the Renaissance spirit spread to Germany and the Low Countries, where the development of the printing press (ca. 1450) and Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) predated the influence from Italy. In the early Protestant areas of the country humanism became closely linked to the turmoil of the Reformation, and the art and writing of the German Renaissance frequently reflected this dispute.[100] However, the Gothic style and medieval scholastic philosophy remained exclusively until the turn of the 16th century. Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg (ruling 1493–1519) was the first truly Renaissance monarch of the Holy Roman Empire.

Hungary

[edit]After Italy, Hungary was the first European country where the Renaissance appeared.[101] The Renaissance style came directly from Italy during the Quattrocento (1400s) to Hungary first in the Central European region, thanks to the development of early Hungarian-Italian relationships — not only in dynastic connections, but also in cultural, humanistic and commercial relations – growing in strength from the 14th century. The relationship between Hungarian and Italian Gothic styles was a second reason – exaggerated breakthrough of walls is avoided, preferring clean and light structures. Large-scale building schemes provided ample and long term work for the artists, for example, the building of the Friss (New) Castle in Buda, the castles of Visegrád, Tata, and Várpalota. In Sigismund's court there were patrons such as Pippo Spano, a descendant of the Scolari family of Florence, who invited Manetto Ammanatini and Masolino da Pannicale to Hungary.[102]

The new Italian trend combined with existing national traditions to create a particular local Renaissance art. Acceptance of Renaissance art was furthered by the continuous arrival of humanist thought in the country. Many young Hungarians studying at Italian universities came closer to the Florentine humanist center, so a direct connection with Florence evolved. The growing number of Italian traders moving to Hungary, specially to Buda, helped this process. New thoughts were carried by the humanist prelates, among them Vitéz János, archbishop of Esztergom, one of the founders of Hungarian humanism.[103] During the long reign of Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg the Royal Castle of Buda became probably the largest Gothic palace of the late Middle Ages. King Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–1490) rebuilt the palace in early Renaissance style and further expanded it.[104][105]

After the marriage in 1476 of King Matthias to Beatrice of Naples, Buda became one of the most important artistic centers of the Renaissance north of the Alps.[106] The most important humanists living in Matthias' court were Antonio Bonfini and the famous Hungarian poet Janus Pannonius.[106] András Hess set up a printing press in Buda in 1472. Matthias Corvinus's library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe's greatest collections of secular books: historical chronicles, philosophic and scientific works in the 15th century. His library was second only in size to the Vatican Library. (However, the Vatican Library mainly contained Bibles and religious materials.)[107] In 1489, Bartolomeo della Fonte of Florence wrote that Lorenzo de' Medici founded his own Greek-Latin library encouraged by the example of the Hungarian king. Corvinus's library is part of UNESCO World Heritage.[108]

Matthias started at least two major building projects.[109] The works in Buda and Visegrád began in about 1479.[110] Two new wings and a hanging garden were built at the royal castle of Buda, and the palace at Visegrád was rebuilt in Renaissance style.[110][111] Matthias appointed the Italian Chimenti Camicia and the Dalmatian Giovanni Dalmata to direct these projects.[110] Matthias commissioned the leading Italian artists of his age to embellish his palaces: for instance, the sculptor Benedetto da Majano and the painters Filippino Lippi and Andrea Mantegna worked for him.[112] A copy of Mantegna's portrait of Matthias survived.[113] Matthias also hired the Italian military engineer Aristotele Fioravanti to direct the rebuilding of the forts along the southern frontier.[114] He had new monasteries built in Late Gothic style for the Franciscans in Kolozsvár, Szeged and Hunyad, and for the Paulines in Fejéregyháza.[115][116] In the spring of 1485, Leonardo da Vinci travelled to Hungary on behalf of Sforza to meet King Matthias Corvinus, and was commissioned by him to paint a Madonna.[117]

Matthias enjoyed the company of Humanists and had lively discussions on various topics with them.[118] The fame of his magnanimity encouraged many scholars—mostly Italian—to settle in Buda.[119] Antonio Bonfini, Pietro Ranzano, Bartolomeo Fonzio, and Francesco Bandini spent many years in Matthias's court.[120][118] This circle of educated men introduced the ideas of Neoplatonism to Hungary.[121][122] Like all intellectuals of his age, Matthias was convinced that the movements and combinations of the stars and planets exercised influence on individuals' life and on the history of nations.[123] Martius Galeotti described him as "king and astrologer", and Antonio Bonfini said Matthias "never did anything without consulting the stars".[124] Upon his request, the famous astronomers of the age, Johannes Regiomontanus and Marcin Bylica, set up an observatory in Buda and installed it with astrolabes and celestial globes.[125] Regiomontanus dedicated his book on navigation that was used by Christopher Columbus to Matthias.[119]

Other important figures of Hungarian Renaissance include Bálint Balassi (poet), Sebestyén Tinódi Lantos (poet), Bálint Bakfark (composer and lutenist), and Master MS (fresco painter).

Low Countries

[edit]

Culture in the Netherlands at the end of the 15th century was influenced by the Italian Renaissance through trade via Bruges, which made Flanders wealthy. Its nobles commissioned artists who became known across Europe.[126] In science, the anatomist Andreas Vesalius led the way; in cartography, Gerardus Mercator's map assisted explorers and navigators. In art, Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting ranged from the strange work of Hieronymus Bosch[127] to the everyday life depictions of Pieter Brueghel the Elder.[126]

Erasmus was arguably the Netherlands' best known humanist and Catholic intellectual during the Renaissance.[34]

Northern Europe

[edit]The Renaissance in Northern Europe has been termed the "Northern Renaissance". While Renaissance ideas were moving north from Italy, there was a simultaneous southward spread of some areas of innovation, particularly in music.[128] The music of the 15th-century Burgundian School defined the beginning of the Renaissance in music, and the polyphony of the Netherlanders, as it moved with the musicians themselves into Italy, formed the core of the first true international style in music since the standardization of Gregorian Chant in the 9th century.[128] The culmination of the Netherlandish school was in the music of the Italian composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. At the end of the 16th century Italy again became a center of musical innovation, with the development of the polychoral style of the Venetian School, which spread northward into Germany around 1600. In Denmark, the Renaissance sparked the translation of the works of Saxo Grammaticus into Danish as well as Frederick II and Christian IV ordering the redecoration or construction of several important works of architecture, i.e. Kronborg, Rosenborg and Børsen.[129] Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe greatly contributed to turn astronomy into the first modern science and also helped launch the Scientific Revolution.[130][131]

The paintings of the Italian Renaissance differed from those of the Northern Renaissance. Italian Renaissance artists were among the first to paint secular scenes, breaking away from the purely religious art of medieval painters. Northern Renaissance artists initially remained focused on religious subjects, such as the contemporary religious upheaval portrayed by Albrecht Dürer. Later, the works of Pieter Bruegel the Elder influenced artists to paint scenes of daily life rather than religious or classical themes. It was also during the Northern Renaissance that Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck perfected the oil painting technique, which enabled artists to produce strong colors on a hard surface that could survive for centuries.[132] A feature of the Northern Renaissance was its use of the vernacular in place of Latin or Greek, which allowed greater freedom of expression. This movement had started in Italy with the decisive influence of Dante Alighieri on the development of vernacular languages; in fact the focus on writing in Italian has neglected a major source of Florentine ideas expressed in Latin.[133] The spread of the printing press technology boosted the Renaissance in Northern Europe as elsewhere, with Venice becoming a world center of printing.

Poland

[edit]The Polish Renaissance lasted from the late 15th to the late 16th century and was the Golden Age of Polish culture. Ruled by the Jagiellonian dynasty, the Kingdom of Poland (from 1569 known as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) actively participated in the broad European Renaissance. An early Italian humanist who came to Poland in the mid-15th century was Filippo Buonaccorsi, who was employed as royal advisor and councillor. The tomb of John I Albert, completed in 1505 by Francesco Fiorentino, is the first example of a Renaissance composition in the country.[134][135] Many Italian artists subsequently came to Poland with Bona Sforza of Milan, when she married King Sigismund I in 1518.[136] This was supported by temporarily strengthened monarchies in both areas, as well as by newly established universities.[137]

The Renaissance was a period when the multi-national Polish state experienced a substantial period of cultural growth thanks in part to a century without major wars, aside from conflicts in the sparsely populated eastern and southern borderlands. Architecture became more refined and decorative. Mannerism played an important part in shaping what is now considered to be the truly Polish architectural style – high attics above the cornice with pinnacles and pilasters.[138] It was also the time when the first major works of Polish literature were published, particularly those of Mikołaj Rey and Jan Kochanowski, and the Polish language became the lingua franca of East-Central Europe.[139] The Jagiellonian University transformed into a major institution of higher education for the region and hosted many notable scholars, chiefly Nicolaus Copernicus and Conrad Celtes. Three more academies were founded at Königsberg (1544), Vilnius (1579), and Zamość (1594). The Reformation spread peacefully throughout the country, giving rise to the Nontrinitarian Polish Brethren.[140] Living conditions improved, cities grew, and exports of agricultural products enriched the population, especially the nobility (szlachta) and magnates. The nobles gained dominance in the new political system of Golden Liberty, a counterweight to monarchical absolutism.[141]

Portugal

[edit]

Although Italian Renaissance had a modest impact in Portuguese arts, Portugal was influential in broadening the European worldview,[142] stimulating humanist inquiry. Renaissance arrived through the influence of wealthy Italian and Flemish merchants who invested in the profitable commerce overseas. As the pioneer headquarters of European exploration, Lisbon flourished in the late 15th century, attracting experts who made several breakthroughs in mathematics, astronomy and naval technology, including Pedro Nunes, João de Castro, Abraham Zacuto, and Martin Behaim. Cartographers Pedro Reinel, Lopo Homem, Estêvão Gomes, and Diogo Ribeiro made crucial advances in mapping the world. Apothecary Tomé Pires and physicians Garcia de Orta and Cristóvão da Costa collected and published works on plants and medicines, soon translated by Flemish pioneer botanist Carolus Clusius.

In architecture, the huge profits of the spice trade financed a sumptuous composite style in the first decades of the 16th century, the Manueline, incorporating maritime elements.[143] The primary painters were Nuno Gonçalves, Gregório Lopes, and Vasco Fernandes. In music, Pedro de Escobar and Duarte Lobo produced four songbooks, including the Cancioneiro de Elvas.

In literature, Luís de Camões inscribed the Portuguese feats overseas in the epic poem Os Lusíadas. Sá de Miranda introduced Italian forms of verse and Bernardim Ribeiro developed pastoral romance, while plays by Gil Vicente fused it with popular culture, reporting the changing times. Travel literature especially flourished: João de Barros, Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, António Galvão, Gaspar Correia, Duarte Barbosa, and Fernão Mendes Pinto, among others, described new lands and were translated and spread with the new printing press.[142] After joining the Portuguese exploration of Brazil in 1500, Amerigo Vespucci coined the term New World,[144] in his letters to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici.

The intense international exchange produced several cosmopolitan humanist scholars, including Francisco de Holanda, André de Resende, and Damião de Góis, a friend of Erasmus who wrote with rare independence on the reign of King Manuel I. Diogo de Gouveia and André de Gouveia made relevant teaching reforms via France. Foreign news and products in the Portuguese factory in Antwerp attracted the interest of Thomas More[145] and Albrecht Dürer to the wider world.[146] There, profits and know-how helped nurture the Dutch Renaissance and Golden Age, especially after the arrival of the wealthy cultured Jewish community expelled from Portugal.

Spain

[edit]

The Renaissance arrived in the Iberian peninsula through the Mediterranean possessions of the Crown of Aragon and the city of Valencia. Many early Spanish Renaissance writers come from the Crown of Aragon, including Ausiàs March and Joanot Martorell. In the Crown of Castile, the early Renaissance was heavily influenced by the Italian humanism, starting with writers and poets such as Íñigo López de Mendoza, marqués de Santillana, who introduced the new Italian poetry to Spain in the early 15th century. Other writers, such as Jorge Manrique, Fernando de Rojas, Juan del Encina, Juan Boscán Almogáver, and Garcilaso de la Vega, kept a close resemblance to the Italian canon. Miguel de Cervantes's masterpiece Don Quixote is credited as the first Western novel. Renaissance humanism flourished in the early 16th century, with influential writers such as philosopher Juan Luis Vives, grammarian Antonio de Nebrija and natural historian Pedro de Mexía. The poet and philosopher Luisa de Medrano, celebrated among her Renaissance contemporaries as one of the puellae doctae ("learned girls"), was the first female professor in Europe at the University of Salamanca.

Later Spanish Renaissance tended toward religious themes and mysticism, with poets such as Luis de León, Teresa of Ávila, and John of the Cross, and treated issues related to the exploration of the New World, with chroniclers and writers such as Inca Garcilaso de la Vega and Bartolomé de las Casas, giving rise to a body of work, now known as Spanish Renaissance literature. The late Renaissance in Spain produced political and religious authors such as Tomás Fernández de Medrano and artists such as El Greco and composers such as Tomás Luis de Victoria and Antonio de Cabezón.

Further countries

[edit]Historiography

[edit]Conception

[edit]

The Italian artist and critic Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) first used the term rinascita in his book The Lives of the Artists (published 1550). In the book Vasari attempted to define what he described as a break with the barbarities of Gothic art: the arts (he held) had fallen into decay with the collapse of the Roman Empire and only the Tuscan artists, beginning with Cimabue (1240–1301) and Giotto (1267–1337) began to reverse this decline in the arts. Vasari saw ancient art as central to the rebirth of Italian art.[147]

However, only in the 19th century did the French word renaissance achieve popularity in describing the self-conscious cultural movement based on revival of Roman models that began in the late 13th century. French historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874) defined "The Renaissance" in his 1855 work Histoire de France as an entire historical period, whereas previously it had been used in a more limited sense.[24] For Michelet, the Renaissance was more a development in science than in art and culture. He asserted that it spanned the period from Columbus to Copernicus to Galileo; that is, from the end of the 15th century to the middle of the 17th century.[98] Moreover, Michelet distinguished between what he called, "the bizarre and monstrous" quality of the Middle Ages and the democratic values that he, as a vocal Republican, chose to see in its character.[19] A French nationalist, Michelet also sought to claim the Renaissance as a French movement.[19]

The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897) in his The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), by contrast, defined the Renaissance as the period between Giotto and Michelangelo in Italy, that is, the 14th to mid-16th centuries. He saw in the Renaissance the emergence of the modern spirit of individuality, which the Middle Ages had stifled.[148] His book was widely read and became influential in the development of the modern interpretation of the Italian Renaissance.[149]

More recently, some historians have been much less keen to define the Renaissance as a historical age, or even as a coherent cultural movement. The historian Randolph Starn, of the University of California Berkeley, stated in 1998:

Rather than a period with definitive beginnings and endings and consistent content in between, the Renaissance can be (and occasionally has been) seen as a movement of practices and ideas to which specific groups and identifiable persons variously responded in different times and places. It would be in this sense a network of diverse, sometimes converging, sometimes conflicting cultures, not a single, time-bound culture.[21]

Debates about progress

[edit]There is debate about the extent to which the Renaissance improved on the culture of the Middle Ages. Both Michelet and Burckhardt were keen to describe the progress made in the Renaissance toward the modern age. Burckhardt likened the change to a veil being removed from man's eyes, allowing him to see clearly.[54]

In the Middle Ages both sides of human consciousness – that which was turned within as that which was turned without – lay dreaming or half awake beneath a common veil. The veil was woven of faith, illusion, and childish prepossession, through which the world and history were seen clad in strange hues.[150]

— Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

On the other hand, many historians now point out that most of the negative social factors popularly associated with the medieval period – poverty, warfare, religious and political persecution, for example – seem to have worsened in this era, which saw the rise of Machiavellian politics, the Wars of Religion, the corrupt Borgia Popes, and the intensified witch-hunts of the 16th century. Many people who lived during the Renaissance did not view it as the "golden age" imagined by certain 19th-century authors, but were concerned by these social maladies.[151] Significantly, though, the artists, writers, and patrons involved in the cultural movements in question believed they were living in a new era that was a clean break from the Middle Ages.[89] Some Marxist historians prefer to describe the Renaissance in material terms, holding the view that the changes in art, literature, and philosophy were part of a general economic trend from feudalism toward capitalism, resulting in a bourgeois class with leisure time to devote to the arts.[152]

Johan Huizinga (1872–1945) acknowledged the existence of the Renaissance but questioned whether it was a positive change. In his book The Autumn of the Middle Ages, he argued that the Renaissance was a period of decline from the High Middle Ages, destroying much that was important.[20] The Medieval Latin language, for instance, had evolved greatly from the classical period and was still a living language used in the church and elsewhere. The Renaissance obsession with classical purity halted its further evolution and saw Latin revert to its classical form. This view is however somewhat contested by recent studies. Robert S. Lopez has contended that it was a period of deep economic recession.[153] Meanwhile, George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike have both argued that scientific progress was perhaps less original than has traditionally been supposed.[154] Finally, Joan Kelly argued that the Renaissance led to greater gender dichotomy, lessening the agency women had had during the Middle Ages.[155]

Some historians have begun to consider the word Renaissance to be unnecessarily loaded, implying an unambiguously positive rebirth from the supposedly more primitive "Dark Ages", the Middle Ages. Most political and economic historians now prefer to use the term "early modern" for this period (and a considerable period afterwards), a designation intended to highlight the period as a transitional one between the Middle Ages and the modern era.[156] Others such as Roger Osborne have come to consider the Italian Renaissance as a repository of the myths and ideals of western history in general, and instead of rebirth of ancient ideas as a period of great innovation.[157]

The art historian Erwin Panofsky observed of this resistance to the concept of "Renaissance":

It is perhaps no accident that the factuality of the Italian Renaissance has been most vigorously questioned by those who are not obliged to take a professional interest in the aesthetic aspects of civilization – historians of economic and social developments, political and religious situations, and, most particularly, natural science – but only exceptionally by students of literature and hardly ever by historians of Art.[158]

Other Renaissances

[edit]The term Renaissance has also been used to define periods outside of the 15th and 16th centuries in the earlier Medieval period. Charles H. Haskins (1870–1937), for example, made a case for a Renaissance of the 12th century.[159] Other historians have argued for a Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries, Ottonian Renaissance in the 10th century and for the Timurid Renaissance of the 14th century. The Islamic Golden Age has been also sometimes termed with the Islamic Renaissance.[160] The Macedonian Renaissance is a term used for a period in the Roman Empire in the 9th-11th centuries CE.

Other periods of cultural rebirth in Modern times have also been termed "renaissances", such as the Bengal Renaissance, Tamil Renaissance, Nepal Bhasa renaissance, al-Nahda or the Harlem Renaissance. The term can also be used in cinema. In animation, the Disney Renaissance is a period that spanned the years from 1989 to 1999 which saw the studio return to the level of quality not witnessed since their Golden Age of Animation. The San Francisco Renaissance was a vibrant period of exploratory poetry and fiction writing in San Francisco in the mid-20th century.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ French: [ʁənɛsɑ̃s] ⓘ, meaning 'rebirth', from renaître 'to be born again'; Italian: Rinascimento [rinaʃʃiˈmento], from rinascere, with the same meanings.[3]

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary cites W Dyce and C H Wilson's Letter to Lord Meadowbank (1837): "A style possessing many points of rude resemblance with the more elegant and refined character of the art of the renaissance in Italy." And the following year in Civil Engineer & Architect's Journal: "Not that we consider the style of the Renaissance to be either pure or good per se." See Oxford English Dictionary, "Renaissance"

- ^ "Historians of different kinds will often make some choice between a long Renaissance (say, 1300–1600), a short one (1453–1527), or somewhere in between (the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as is commonly adopted in music histories)."[8] Or between Petrarch and Jonathan Swift, an even longer period.[9] Another source dates it from 1350 to 1620.[10]

- ^ Some scholars have called for an end to the use of the term, which they see as a product of presentism – the use of history to validate and glorify modern ideals.[23]

- ^ For information on this earlier, very different approach to a different set of ancient texts (scientific texts rather than cultural texts) see Latin translations of the 12th century, and Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe.

- ^ It is thought that Leonardo da Vinci may have painted the rhombicuboctahedron.[71]

- ^ Exhaustive 2007 study by Fritjof Capra shows that Leonardo was a much greater scientist than previously thought, and not just an inventor. Leonardo was innovative in science theory and in conducting actual science practice. In Capra's detailed assessment of many surviving manuscripts, Leonardo's science in tune with holistic non-mechanistic and non-reductive approaches to science, which are becoming popular today.[72]

- ^ Joseph Ben-David wrote:

Rapid accumulation of knowledge, which has characterized the development of science since the 17th century, had never occurred before that time. The new kind of scientific activity emerged only in a few countries of Western Europe, and it was restricted to that small area for about two hundred years. (Since the 19th century, scientific knowledge has been assimilated by the rest of the world).

- ^ It is sometimes thought that the Church, as an institution, formally sold indulgences at the time. This, however, was not the practice. Donations were often received, but only mandated by individuals that were condemned.

Citations

[edit]- ^ "renaissance". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ Wells, John (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1405881180.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary: "Renaissance"". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- ^ Brotton, Jerry (2006). The Renaissance: a very short introduction (1. publ ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-19-280163-0.

- ^ "BBC Science | Learn about Leonardo da Vinci". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 October 2025.

- ^ "BBC - History - Michelangelo". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 October 2025.

- ^ a b Diwan, Jaswith. Accounting Concepts & Theories. London: Morre. pp. 1–2. id# 94452.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music: Volume 1, p. 4, 2005, Cambridge University Press, Google Books.

- ^ See Rosalie L. Colie, quoted in Hageman, Elizabeth H., in Women and Literature in Britain, 1500–1700, p. 190, 1996, ed. Helen Wilcox, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521467773, Google Books.

- ^ "Renaissance Era Dates". encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Monfasani, John (2016). Renaissance Humanism, from the Middle Ages to Modern Times. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1351904391.

- ^ Boia, Lucian (2004). Forever Young: A Cultural History of Longevity. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1861891549.

- ^ Burke, P., The European Renaissance: Centre and Peripheries 1998

- ^ "The Renaissance: At a Glance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ a b Strathern, Paul The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance (2003)

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica, "Renaissance", 2008, O.Ed.

- ^ Harris, Michael H. History of Libraries in the Western World, Scarecrow Press Incorporate, 1999, p. 69, ISBN 0810837242

- ^ Norwich, John Julius, A Short History of Byzantium, 1997, Knopf, ISBN 0679450882

- ^ a b c d Brotton, J., The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction, OUP, 2006 ISBN 0192801635.

- ^ a b Huizanga, Johan, The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919, trans. 1924)

- ^ a b Starn, Randolph (1998). "Renaissance Redux". The American Historical Review. 103 (1): 122–124. doi:10.2307/2650779. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 2650779.

- ^ Panofsky 1969:6.

- ^ Trinkaus, Charles; Rabil, Albert; Purnell, Frederick (1990). "Renaissance Ideas and the Idea of the Renaissance". Journal of the History of Ideas. 51 (4): 667–684. doi:10.2307/2709652. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709652.

- ^ a b Murray, P. and Murray, L. (1963) The Art of the Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson (World of Art), p. 9. ISBN 978-0500200087. "...in 1855 we find, for the first time, the word 'Renaissance' used – by the French historian Michelet – as an adjective to describe a whole period of history and not confined to the rebirth of Latin letters or a classically inspired style in the arts."

- ^ Perry, M. Humanities in the Western Tradition Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Ch. 13

- ^ Kennedy, Lesley (27 September 2021). "How the Renaissance Challenged the Church and Influenced the Reformation". HISTORY. Retrieved 26 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d Open University, Looking at the Renaissance: Religious Context in the Renaissance (Retrieved 10 May 2007)

- ^ "The Open University". fass.open.ac.uk. 12 October 2025. Retrieved 26 October 2025.

- ^ Kohn, Hans (1944). The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ Stark, Rodney, The Victory of Reason, Random House, NY: 2005

- ^ Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2017). The Medieval Frontiers of Latin Christendom. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Leon Poliakov, The Aryan Myth: A History of Racist and Nationalist Ideas in Europe, trans. E. Howard (Basic Books, 1974), pp. 21–22, cited in Fernandez-Armesto (2017)

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert, The Feud that sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World (New York, Perennial-Harper Collins, 2003)

- ^ a b Rietbergen, P. J. A. N. (2000). A Short History of the Netherlands: From Prehistory to the Present Day (4th ed.). Amersfoort: Bekking. p. 59. ISBN 90-6109-440-2. OCLC 52849131.

- ^ Reynolds & Wilson 1974, pp. 113–123

- ^ Reynolds & Wilson 1974, pp. 123, 130–137

- ^ Truxillo, Charles A. (2008). Periods of World History: A Latin American Perspective. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89581-863-8.

- ^ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ^ Harris, Michael H. History of Libraries in the Western World, Scarecrow Press, 1999, p. 145, ISBN 0810837242.

- ^ Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, Margaret C. Jacob, James R. Jacob, 2008, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Reynolds & Wilson 1974, pp. 119, 131

- ^ Kirshner, Julius, Family and Marriage: A socio-legal perspective, Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300–1550, ed. John M. Najemy (Oxford University Press, 2004) p. 89 (Retrieved 10 May 2007)

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob, The Revival of Antiquity, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy Archived 7 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine (trans. by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878)

- ^ a b Skinner, Quentin, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol I: The Renaissance; vol II: The Age of Reformation, Cambridge University Press, p. 69

- ^ Stark, Rodney, The Victory of Reason, New York, Random House, 2005

- ^ Martin, J. and Romano, D., Venice Reconsidered, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University, 2000

- ^ a b Burckhardt, Jacob, The Republics: Venice and Florence, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy Archived 7 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine, translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878.

- ^ Barbara Tuchman (1978) A Distant Mirror, Knopf ISBN 0394400267.

- ^ The End of Europe's Middle Ages: The Black Death Archived 9 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine University of Calgary website. (Retrieved 5 April 2007)

- ^ Netzley, Patricia D. Life During the Renaissance. San Diego: Lucent Books, Inc., 1998.

- ^ Hause, S. & Maltby, W. (2001). A History of European Society. Essentials of Western Civilization (Vol. 2, p. 217). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning, Inc.

- ^ "Renaissance And Reformation France" Mack P. Holt pp. 30, 39, 69, 166

- ^ Hatty, Suzanne E.; Hatty, James (1999). Disordered Body: Epidemic Disease and Cultural Transformation. SUNY Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0791443651.

- ^ a b Burckhardt, Jacob, The Development of the Individual, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878.

- ^ Stephens, J., Individualism and the cult of creative personality, The Italian Renaissance, New York, 1990 p. 121.

- ^ Guido Carocci, I dintorni di Firenze, Vol. II, Galletti e Cocci, Firenze, 1907, pp. 336–337

- ^ Burke, P., "The spread of Italian humanism", in The Impact of Humanism on Western Europe, ed. A. Goodman and A. MacKay, London, 1990, p. 2.

- ^ As asserted by Gianozzo Manetti in On the Dignity and Excellence of Man, cited in Clare, J., Italian Renaissance.

- ^ Pico Della Mirandola. "Oration on the Dignity of Man". Reading About the World, Volume 1. Translated by Hooker, Richard. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011 – via World Civilizations at Washington State University.

- ^ Miller, John H. Ibn Khaldun and Machiavelli : an examination of paradigms. OCLC 11117374.

- ^ Religion and Political Development: Some Comparative Ideas on Ibn Khaldun and Machiavelli by Barbara Freyer Stowasser

- ^ Hause, S. & Maltby, W. (2001). A History of European Society. Essentials of Western Civilization (Vol. 2, pp. 245–246). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning, Inc.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 88.

- ^ Clare, John D. & Millen, Alan, Italian Renaissance, London, 1994, p. 14.

- ^ Stork, David G. Optics and Realism in Renaissance Art Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine (Retrieved 10 May 2007)

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio, Lives of the Artists, translated by George Bull, Penguin Classics, 1965, ISBN 0140441646.

- ^ Peter Brueghel Biography, Web Gallery of Art (Retrieved 10 May 2007)

- ^ Hooker, Richard, Architecture and Public Space Archived 22 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine (Retrieved 10 May 2007)

- ^ Saalman, Howard (1993). Filippo Brunelleschi: The Buildings. Zwemmer. ISBN 978-0271010670.

- ^ Hause, S. & Maltby, W. (2001). A History of European Society. Essentials of Western Civilization (Vol. 2, pp. 250–251). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning, Inc.

- ^ MacKinnon, Nick (1993). "The Portrait of Fra Luca Pacioli". The Mathematical Gazette. 77 (479): 143. doi:10.2307/3619717. JSTOR 3619717. S2CID 195006163.

- ^ Capra, Fritjof, The Science of Leonardo; Inside the Mind of the Great Genius of the Renaissance, New York, Doubleday, 2007.

- ^ "Columbus and Vesalius – The Age of Discoverers". JAMA. 2015;313(3):312. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.11534

- ^ Allen Debus, Man and Nature in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

- ^ Butterfield, Herbert, The Origins of Modern Science, 1300–1800, p. viii

- ^ Shapin, Steven. The Scientific Revolution, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 1.

- ^ "Scientific Revolution" in Encarta. 2007. [1]

- ^ a b Brotton, J., "Science and Philosophy", The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2006 ISBN 0192801635.

- ^ Van Doren, Charles (1991) A History of Knowledge Ballantine, New York, pp. 211–212, ISBN 0345373162

- ^ Burke, Peter (2000) A Social History of Knowledge: From Gutenberg to Diderot Polity Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, p. 40, ISBN 0745624847

- ^ Hunt, Shelby D. (2003). Controversy in marketing theory: for reason, realism, truth, and objectivity. M.E. Sharpe. p. 18. ISBN 978-0765609328.