Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

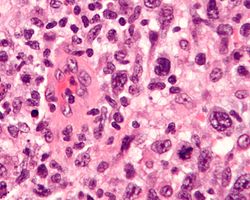

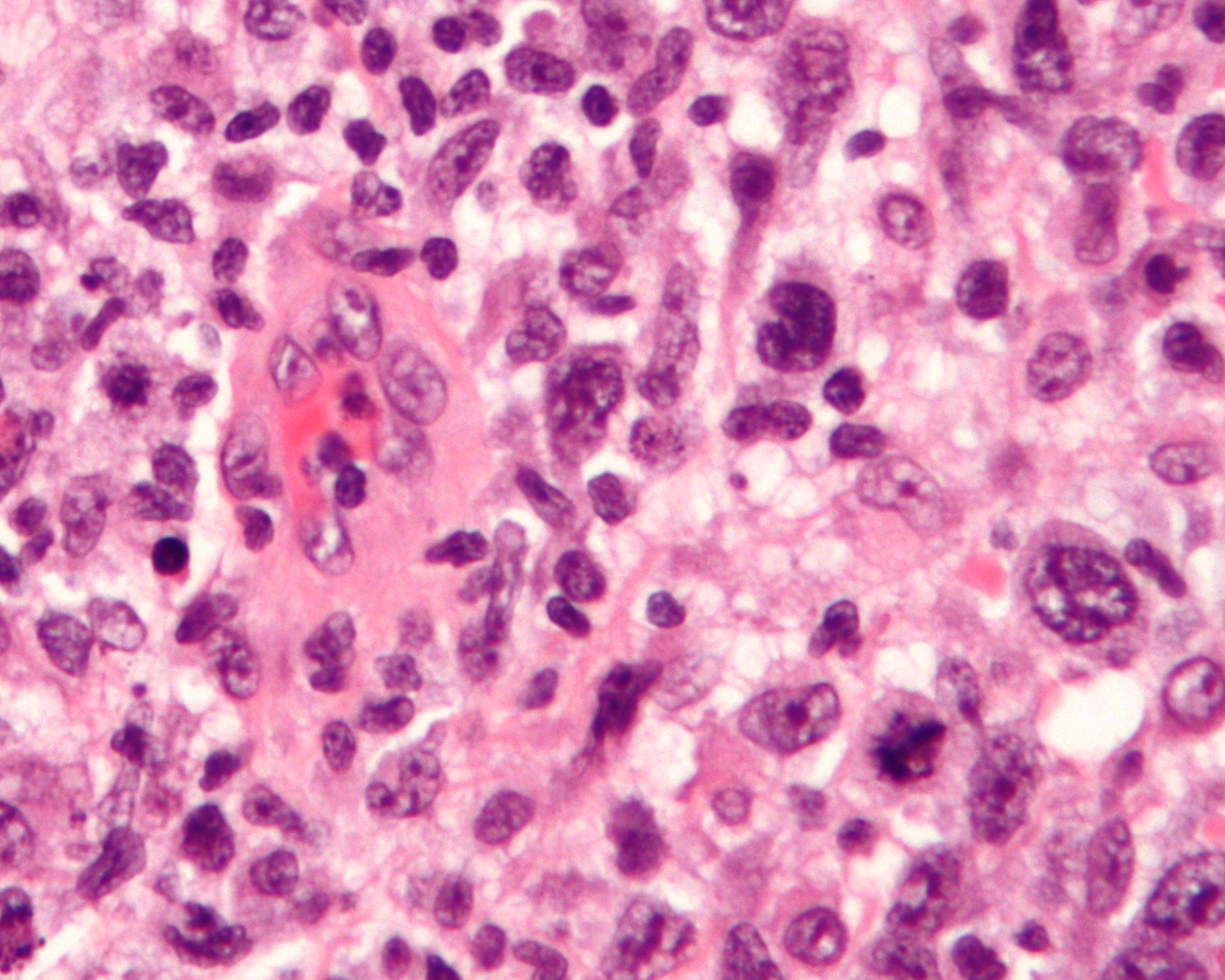

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of large, abnormal T-cells or null lymphocytes that express the CD30 antigen on their surface.[1][2] It is classified into systemic ALCL (which can be ALK-positive or ALK-negative), primary cutaneous ALCL (confined to the skin), and breast implant-associated ALCL (BIA-ALCL), with the ALK status reflecting the presence of anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene rearrangements that drive oncogenesis.[1][3] This aggressive malignancy accounts for approximately 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas in adults and up to 30% in children, predominantly affecting males and varying in presentation from localized skin lesions to widespread systemic involvement.[2][4]

Systemic ALCL, the most common form, often presents with B symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss, alongside lymphadenopathy and extranodal sites like skin, bone, or soft tissue.[1][2] ALK-positive cases, typically seen in younger patients (median age around 24 years), arise from the t(2;5)(p23;q35) chromosomal translocation resulting in the NPM-ALK fusion protein, which activates pathways like JAK/STAT and PI3K/AKT to promote cell survival and proliferation.[3] In contrast, ALK-negative systemic ALCL affects older adults (median age 61 years) and involves alternative genetic alterations, such as DUSP22 rearrangements or TP53 mutations, leading to a more heterogeneous and often poorer prognosis.[2][3]

Primary cutaneous ALCL manifests as solitary or multifocal reddish-brown nodules on the skin and has an indolent course, with about 25% of cases showing spontaneous regression and a 5-year survival rate exceeding 90%.[1][2] BIA-ALCL, a distinct entity linked to textured breast implants, usually develops 7-10 years post-implantation as a seroma or capsule mass, driven by chronic inflammation and STAT3 mutations, and is curable in over 90% of noninvasive cases through implant removal.[1][2] Diagnosis across subtypes relies on excisional biopsy with immunohistochemistry confirming CD30 positivity and ALK status, supplemented by imaging (PET/CT) and staging to guide therapy.[4][2]

Treatment strategies are subtype-specific: ALK-positive systemic ALCL responds well to multi-agent chemotherapy like CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) with or without brentuximab vedotin, achieving 5-year survival rates of 70-90%, while relapsed cases may require stem cell transplantation.[1][2] For ALK-negative disease, outcomes are inferior (5-year survival 15-45%), often necessitating intensified regimens or targeted therapies against CD30 or JAK/STAT pathways.[2][3] Cutaneous and BIA-ALCL typically require localized interventions like surgery or radiation, with systemic therapy reserved for advanced disease.[1] Overall, early detection and ALK stratification significantly improve prognosis in this T-cell lymphoma.[4][2]