Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cell division

View on Wikipedia

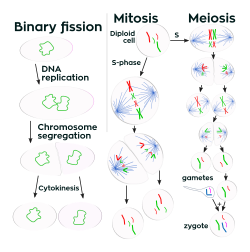

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells.[1] Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there are two distinct types of cell division: a vegetative division (mitosis), producing daughter cells genetically identical to the parent cell, and a cell division that produces haploid gametes for sexual reproduction (meiosis), reducing the number of chromosomes from two of each type in the diploid parent cell to one of each type in the daughter cells.[2] Mitosis is a part of the cell cycle, in which, replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is maintained. In general, mitosis (division of the nucleus) is preceded by the S stage of interphase (during which the DNA replication occurs) and is followed by telophase and cytokinesis; which divides the cytoplasm, organelles, and cell membrane of one cell into two new cells containing roughly equal shares of these cellular components. The different stages of mitosis all together define the M phase of an animal cell cycle—the division of the mother cell into two genetically identical daughter cells.[3]

To ensure proper progression through the cell cycle, DNA damage is detected and repaired at various cell cycle checkpoints. These checkpoints can halt progression through the cell cycle by inhibiting certain cyclin-CDK complexes. Meiosis undergoes two divisions resulting in four haploid daughter cells. Homologous chromosomes are separated in the first division of meiosis, such that each daughter cell has one copy of each chromosome. These chromosomes have already been replicated and have two sister chromatids which are then separated during the second division of meiosis.[4] Both of these cell division cycles are used in the process of sexual reproduction at some point in their life cycle. Both are believed to be present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor.

Prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) usually undergo a vegetative cell division known as binary fission, where their genetic material is segregated equally into two daughter cells, but there are alternative manners of division, such as budding, that have been observed. All cell divisions, regardless of organism, are preceded by a single round of DNA replication.

For simple unicellular microorganisms such as the amoeba, one cell division is equivalent to reproduction – an entire new organism is created. On a larger scale, mitotic cell division can create progeny from multicellular organisms, such as plants that grow from cuttings. Mitotic cell division enables sexually reproducing organisms to develop from the one-celled zygote, which itself is produced by fusion of two gametes, each having been produced by meiotic cell division.[5][6] After growth from the zygote to the adult, cell division by mitosis allows for continual construction and repair of the organism.[7] The human body experiences about 10 quadrillion cell divisions in a lifetime.[8]

The primary concern of cell division is the maintenance of the original cell's genome. Before division can occur, the genomic information that is stored in chromosomes must be replicated, and the duplicated genome must be cleanly divided between progeny cells.[9] A great deal of cellular infrastructure is involved in ensuring consistency of genomic information among generations.[10][11][12]

In bacteria

[edit]

Bacterial cell division happens through binary fission or through budding. The divisome is a protein complex in bacteria that is responsible for cell division, constriction of inner and outer membranes during division, and remodeling of the peptidoglycan cell wall at the division site. A tubulin-like protein, FtsZ plays a critical role in formation of a contractile ring for the cell division.[14]

In eukaryotes

[edit]Cell division in eukaryotes is more complicated than in prokaryotes. If the chromosomal number is reduced, eukaryotic cell division is classified as meiosis (reductional division). If the chromosomal number is not reduced, eukaryotic cell division is classified as mitosis (equational division). A primitive form of cell division, called amitosis, also exists. The amitotic or mitotic cell divisions are more atypical and diverse among the various groups of organisms, such as protists (namely diatoms, dinoflagellates, etc.) and fungi.[citation needed]

In the mitotic metaphase (see below), typically the chromosomes (each containing 2 sister chromatids that developed during replication in the S phase of interphase) align themselves on the metaphase plate. Then, the sister chromatids split and are distributed between two daughter cells.[citation needed]

In meiosis I, the homologous chromosomes are paired before being separated and distributed between two daughter cells. On the other hand, meiosis II is similar to mitosis. The chromatids are separated and distributed in the same way. In humans, other higher animals, and many other organisms, the process of meiosis is called gametic meiosis, during which meiosis produces four gametes. Whereas, in several other groups of organisms, especially in plants (observable during meiosis in lower plants, but during the vestigial stage in higher plants), meiosis gives rise to spores that germinate into the haploid vegetative phase (gametophyte). This kind of meiosis is called "sporic meiosis."[citation needed]

Phases of eukaryotic cell division

[edit]

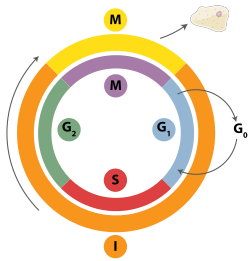

Interphase

[edit]Interphase is the process through which a cell must go before mitosis, meiosis, and cytokinesis.[15] Interphase consists of three main phases: G1, S, and G2. G1 is a time of growth for the cell where specialized cellular functions occur in order to prepare the cell for DNA replication.[16] There are checkpoints during interphase that allow the cell to either advance or halt further development. One of the checkpoint is between G1 and S, the purpose for this checkpoint is to check for appropriate cell size and any DNA damage . The second check point is in the G2 phase, this checkpoint also checks for cell size but also the DNA replication. The last check point is located at the site of metaphase, where it checks that the chromosomes are correctly connected to the mitotic spindles.[17] In S phase, the chromosomes are replicated in order for the genetic content to be maintained.[18] During G2, the cell undergoes the final stages of growth before it enters the M phase, where spindles are synthesized. The M phase can be either mitosis or meiosis depending on the type of cell. Germ cells, or gametes, undergo meiosis, while somatic cells will undergo mitosis. After the cell proceeds successfully through the M phase, it may then undergo cell division through cytokinesis. The control of each checkpoint is controlled by cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinases. The progression of interphase is the result of the increased amount of cyclin. As the amount of cyclin increases, more and more cyclin dependent kinases attach to cyclin signaling the cell further into interphase. At the peak of the cyclin, attached to the cyclin dependent kinases this system pushes the cell out of interphase and into the M phase, where mitosis, meiosis, and cytokinesis occur.[19] There are three transition checkpoints the cell has to go through before entering the M phase. The most important being the G1-S transition checkpoint. If the cell does not pass this checkpoint, it results in the cell exiting the cell cycle.[20]

Prophase

[edit]Prophase is the first stage of division. The nuclear envelope begins to be broken down in this stage, long strands of chromatin condense to form shorter more visible strands called chromosomes, the nucleolus disappears, and the mitotic spindle begins to assemble from the two centrosomes.[21] Microtubules associated with the alignment and separation of chromosomes are referred to as the spindle and spindle fibers. Chromosomes will also be visible under a microscope and will be connected at the centromere. During this condensation and alignment period in meiosis, the homologous chromosomes undergo a break in their double-stranded DNA at the same locations, followed by a recombination of the now fragmented parental DNA strands into non-parental combinations, known as crossing over.[22] This process is evidenced to be caused in a large part by the highly conserved Spo11 protein through a mechanism similar to that seen with topoisomerase in DNA replication and transcription.[23]

Prometaphase

[edit]Prometaphase is the second stage of cell division. This stage begins with the complete breakdown of the nuclear envelope which exposes various structures to the cytoplasm. This breakdown then allows the spindle apparatus growing from the centrosome to attach to the kinetochores on the sister chromatids. Stable attachment of the spindle apparatus to the kinetochores on the sister chromatids will ensure error-free chromosome segregation during anaphase.[24] Prometaphase follows prophase and precedes metaphase.

Metaphase

[edit]In metaphase, the centromeres of the chromosomes align themselves on the metaphase plate (or equatorial plate), an imaginary line that is at equal distances from the two centrosome poles and held together by complexes known as cohesins. Chromosomes line up in the middle of the cell by microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs) pushing and pulling on centromeres of both chromatids thereby causing the chromosome to move to the center. At this point the chromosomes are still condensing and are currently one step away from being the most coiled and condensed they will be, and the spindle fibers have already connected to the kinetochores.[25] During this phase all the microtubules, with the exception of the kinetochores, are in a state of instability promoting their progression toward anaphase.[26] At this point, the chromosomes are ready to split into opposite poles of the cell toward the spindle to which they are connected.[27]

Anaphase

[edit]Anaphase is a very short stage of the cell cycle and it occurs after the chromosomes align at the mitotic plate. Kinetochores emit anaphase-inhibition signals until their attachment to the mitotic spindle. Once the final chromosome is properly aligned and attached the final signal dissipates and triggers the abrupt shift to anaphase.[26] This abrupt shift is caused by the activation of the anaphase-promoting complex and its function of tagging degradation of proteins important toward the metaphase-anaphase transition. One of these proteins that is broken down is securin which through its breakdown releases the enzyme separase that cleaves the cohesin rings holding together the sister chromatids thereby leading to the chromosomes separating.[28] After the chromosomes line up in the middle of the cell, the spindle fibers will pull them apart. The chromosomes are split apart while the sister chromatids move to opposite sides of the cell.[29] As the sister chromatids are being pulled apart, the cell and plasma are elongated by non-kinetochore microtubules.[30] Additionally, in this phase, the activation of the anaphase promoting complex through the association with Cdh-1 begins the degradation of mitotic cyclins.[31]

Telophase

[edit]Telophase is the last stage of the cell cycle in which a cleavage furrow splits the cells cytoplasm (cytokinesis) and chromatin. This occurs through the synthesis of a new nuclear envelope that forms around the chromatin gathered at each pole. The nucleolus reforms as the chromatin reverts back to the loose state it possessed during interphase.[32][33] The division of the cellular contents is not always equal and can vary by cell type as seen with oocyte formation where one of the four daughter cells possess the majority of the duckling.[34]

Cytokinesis

[edit]The last stage of the cell division process is cytokinesis. In this stage there is a cytoplasmic division that occurs at the end of either mitosis or meiosis. At this stage there is a resulting irreversible separation leading to two daughter cells. Cell division plays an important role in determining the fate of the cell. This is due to there being the possibility of an asymmetric division. This as a result leads to cytokinesis producing unequal daughter cells containing completely different amounts or concentrations of fate-determining molecules.[35]

In animals the cytokinesis ends with formation of a contractile ring and thereafter a cleavage. But in plants it happen differently. At first a cell plate is formed and then a cell wall develops between the two daughter cells.[36]

In Fission yeast (S. pombe) the cytokinesis happens in G1 phase.[37]

Variants

[edit]

Cells are broadly classified into two main categories: simple non-nucleated prokaryotic cells and complex nucleated eukaryotic cells. Due to their structural differences, eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells do not divide in the same way. Also, the pattern of cell division that transforms eukaryotic stem cells into gametes (sperm cells in males or egg cells in females), termed meiosis, is different from that of the division of somatic cells in the body.

In 2022, scientists discovered a new type of cell division called asynthetic fission found in the squamous epithelial cells in the epidermis of juvenile zebrafish. When juvenile zebrafish are growing, skin cells must quickly cover the rapidly increasing surface area of the zebrafish. These skin cells divide without duplicating their DNA (the S phase of mitosis) causing up to 50% of the cells to have a reduced genome size. These cells are later replaced by cells with a standard amount of DNA. Scientists expect to find this type of division in other vertebrates.[39]

DNA damage repair in the cell cycle

[edit]DNA damage is detected and repaired at various points in the cell cycle. The G1/S checkpoint, G2/M checkpoint, and the checkpoint between metaphase and anaphase all monitor for DNA damage and halt cell division by inhibiting different cyclin-CDK complexes. The p53 tumor-suppressor protein plays a crucial role at the G1/S checkpoint and the G2/M checkpoint. Activated p53 proteins result in the expression of many proteins that are important in cell cycle arrest, repair, and apoptosis. At the G1/S checkpoint, p53 acts to ensure that the cell is ready for DNA replication, while at the G2/M checkpoint p53 acts to ensure that the cells have properly duplicated their content before entering mitosis.[40]

Specifically, when DNA damage is present, ATM and ATR kinases are activated, activating various checkpoint kinases.[41] These checkpoint kinases phosphorylate p53, which stimulates the production of different enzymes associated with DNA repair.[42] Activated p53 also upregulates p21, which inhibits various cyclin-cdk complexes. These cyclin-cdk complexes phosphorylate the Retinoblastoma (Rb) protein, a tumor suppressor bound with the E2F family of transcription factors. The binding of this Rb protein ensures that cells do not enter the S phase prematurely; however, if it is not able to be phosphorylated by these cyclin-cdk complexes, the protein will remain, and the cell will be halted in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.[43]

If DNA is damaged, the cell can also alter the Akt pathway in which BAD is phosphorylated and dissociated from Bcl2, thus inhibiting apoptosis. If this pathway is altered by a loss of function mutation in Akt or Bcl2, then the cell with damaged DNA will be forced to undergo apoptosis.[44] If the DNA damage cannot be repaired, activated p53 can induce cell death by apoptosis. It can do so by activating the p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA). PUMA is a pro-apoptotic protein that rapidly induces apoptosis by inhibiting the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members.[45]

Degradation

[edit]Multicellular organisms replace worn-out cells through cell division. In some animals, however, cell division eventually halts. In humans this occurs, on average, after 52 divisions, known as the Hayflick limit. The cell is then referred to as senescent. With each division the cells telomeres, protective sequences of DNA on the end of a chromosome that prevent degradation of the chromosomal DNA, shorten. This shortening has been correlated to negative effects such as age-related diseases and shortened lifespans in humans.[46][47] Cancer cells, on the other hand, are not thought to degrade in this way, if at all. An enzyme complex called telomerase, present in large quantities in cancerous cells, rebuilds the telomeres through synthesis of telomeric DNA repeats, allowing division to continue indefinitely.[48]

History

[edit]

At the beginning of the 19th century, various hypotheses circulated about cell proliferation, which became observable in plant and animal organisms as a result of advances in microscopy. While the proliferation of cells on the inner side of old cells,[49][50] the attachment of vesicles to existing cells,[51] or crystallization in the intercellular space[52] were postulated as mechanisms of cell proliferation, proponents of cell division itself had to fight for its acceptance for decades.

The Belgian botanist Barthélemy Charles Joseph Dumortier must be regarded as the first discoverer of cell division. In 1832, he described cell division in simple aquatic plants (French 'conferve') as follows (translated from French to English):

"The development of the conferve is as simple as its structure; it takes place by the attachment of new cells to the old, and this attachment always takes place from the end. The terminal cell elongates more than the deeper cells; then the production of a lateral bisector takes place in the inner fluid, which tends to divide the cell into two parts, of which the deeper one remains stationary, while the terminal part elongates again, forms a new inner partition, and so on. Is the production of the middle partition originally double or single? It is impossible to determine this, but it is always true that it later appears double when united, and that when two cells naturally separate, each of them is closed at both ends."[53]

In 1835, the German botanist and physician Hugo von Mohl described plant cell division in much greater detail in his dissertation on freshwater and seawater algae for his PhD thesis in medicine and surgery:[54]

"Among the most obscure phenomena of plant life is the manner in which the newly developing cells are formed. [...] and so there is no lack of manifold descriptions and explanations of this process. [...] and that gaps that were found in the observations were filled in by overly bold conclusions and assumptions." (translated from German to English)

In 1838, the German physician and botanist Franz Julius Ferdinand Meyen confirmed the mechanism of cell division at the root tips of plants.[55] The German-Polish physician Robert Remak suspected that he had already discovered animal cell division in the blood of chicken embryos in 1841,[56] but it was not until 1852 that he was able to confirm animal cell division for the first time in bird embryos, frog larvae and mammals.[57]

In 1943, cell division was filmed for the first time[58] by Kurt Michel using a phase-contrast microscope.[59]

See also

[edit]- Cell fusion

- Cell growth

- Cyclin-dependent kinase

- Labile cells, cells that constantly divide

- Mitotic catastrophe

References

[edit]- ^ Martin EA, Hine R (2020). A dictionary of biology (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920462-5. OCLC 176818780.

- ^ Griffiths AJ (2012). Introduction to genetic analysis (10th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 978-1-4292-2943-2. OCLC 698085201.

- ^ "10.2 The Cell Cycle – Biology 2e | OpenStax". openstax.org. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000), "Meiosis", Developmental Biology. 6th edition, Sinauer Associates, retrieved 2023-09-08

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). "Spermatogenesis". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). "Oogenesis". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Maton, Anthea (1997). Cells: building blocks of life (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. pp. 70–74. ISBN 978-0-13-423476-2. OCLC 37049921.

- ^ Quammen D (April 2008). "Contagious Cancer". Harper's Magazine. ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ^ Golitsin, Yuri N.; Krylov, Mikhail C. C. (2010). Cell division: theory, variants, and degradation. New York: Nova Science Publishers. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-61122-593-8. OCLC 669515286.

- ^ Fletcher, Daniel A.; Mullins, R. Dyche (28 January 2010). "Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton". Nature. 463 (7280): 485–492. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..485F. doi:10.1038/nature08908. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 2851742. PMID 20110992.

- ^ Li, Shanwei; Sun, Tiantian; Ren, Haiyun (27 April 2015). "The functions of the cytoskeleton and associated proteins during mitosis and cytokinesis in plant cells". Frontiers in Plant Science. 6: 282. Bibcode:2015FrPS....6..282L. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00282. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 4410512. PMID 25964792.

- ^ Hohmann, Tim; Dehghani, Faramarz (18 April 2019). "The Cytoskeleton—A Complex Interacting Meshwork". Cells. 8 (4): 362. doi:10.3390/cells8040362. ISSN 2073-4409. PMC 6523135. PMID 31003495.

- ^ Hugonnet JE, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Monton A, den Blaauwen T, Carbonnelle E, Veckerlé C, et al. (October 2016). "Escherichia coli". eLife. 5. doi:10.7554/elife.19469. PMC 5089857. PMID 27767957.

- ^ Cell Division: The Cycle of the Ring, Lawrence Rothfield and Sheryl Justice, CELL, DOI

- ^ Marieb EN (2000). Essentials of human anatomy and physiology (6th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-4940-5. OCLC 41266267.

- ^ Pardee AB (November 1989). "G1 events and regulation of cell proliferation". Science. 246 (4930): 603–8. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..603P. doi:10.1126/science.2683075. PMID 2683075.

- ^ Molinari M (October 2000). "Cell cycle checkpoints and their inactivation in human cancer". Cell Proliferation. 33 (5): 261–74. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2184.2000.00191.x. PMC 6496592. PMID 11063129.

- ^ Morgan DO (2007). The cell cycle: principles of control. London: New Science Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920610-0. OCLC 70173205.

- ^ Lindqvist A, van Zon W, Karlsson Rosenthal C, Wolthuis RM (May 2007). "Cyclin B1-Cdk1 activation continues after centrosome separation to control mitotic progression". PLOS Biology. 5 (5) e123. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050123. PMC 1858714. PMID 17472438.

- ^ Paulovich AG, Toczyski DP, Hartwell LH (February 1997). "When checkpoints fail". Cell. 88 (3): 315–21. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81870-X. PMID 9039258. S2CID 5530166.

- ^ Schermelleh L, Carlton PM, Haase S, Shao L, Winoto L, Kner P, et al. (June 2008). "Subdiffraction multicolor imaging of the nuclear periphery with 3D structured illumination microscopy". Science. 320 (5881): 1332–6. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1332S. doi:10.1126/science.1156947. PMC 2916659. PMID 18535242.

- ^ Griffiths AJ, Gelbart WM, Miller JH, Lewontin RC (1999). "The Mechanism of Crossing-Over". Modern Genetic Analysis. W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 152.

- ^ Keeney S (2001). Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Vol. 52. Elsevier. pp. 1–53. doi:10.1016/s0070-2153(01)52008-6. ISBN 978-0-12-153152-2. PMID 11529427.

- ^ Lian, A.T.Y.; Chircop, M. (2016). "Mitosis in Animal Cells". Encyclopedia of Cell Biology. pp. 298–313. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-821618-7.30064-5. ISBN 978-0-12-821624-8.

- ^ "Researchers Shed Light On Shrinking Of Chromosomes". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ^ a b Walter P, Roberts K, Raff M, Lewis J, Johnson A, Alberts B (2002). "Mitosis". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

- ^ Elrod S (2010). Schaum's outlines: genetics (5th ed.). New York: Mcgraw-Hill. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-07-162503-6. OCLC 473440643.

- ^ Brooker AS, Berkowitz KM (2014). "The Roles of Cohesins in Mitosis, Meiosis, and Human Health and Disease". Cell Cycle Control. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1170. New York: Springer. pp. 229–66. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0888-2_11. ISBN 978-1-4939-0887-5. PMC 4495907. PMID 24906316.

- ^ "The Cell Cycle". www.biology-pages.info. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- ^ Urry LA, Cain ML, Jackson RB, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Reece JB (2014). Campbell Biology in Focus. Boston (Massachusetts): Pearson. ISBN 978-0-321-81380-0.

- ^ Barford, David (2011-12-12). "Structural insights into anaphase-promoting complex function and mechanism". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 366 (1584): 3605–3624. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0069. PMC 3203452. PMID 22084387.

- ^ Dekker J (2014-11-25). "Two ways to fold the genome during the cell cycle: insights obtained with chromosome conformation capture". Epigenetics & Chromatin. 7 (1) 25. doi:10.1186/1756-8935-7-25. PMC 4247682. PMID 25435919.

- ^ Hetzer MW (March 2010). "The nuclear envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (3) a000539. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMC 2829960. PMID 20300205.

- ^ Gilbert SF (2000). "Oogenesis". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Guertin DA, Trautmann S, McCollum D (June 2002). "Cytokinesis in eukaryotes". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 66 (2): 155–78. doi:10.1128/MMBR.66.2.155-178.2002. PMC 120788. PMID 12040122.

- ^ Smith, Laurie G (December 1999). "Divide and conquer: cytokinesis in plant cells". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2 (6): 447–453. Bibcode:1999COPB....2..447S. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(99)00022-9. PMID 10607656.

- ^ The Cell, G.M. Cooper; ed 2 NCBI bookshelf, The eukaryotic cell cycle, Figure 14.7

- ^ "Phase Holographic Imaging of Cell Division". Internet archive. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013.

- ^ Chan KY, Yan CC, Roan HY, Hsu SC, Tseng TL, Hsiao CD, et al. (April 2022). "Skin cells undergo asynthetic fission to expand body surfaces in zebrafish". Nature. 605 (7908): 119–125. Bibcode:2022Natur.605..119C. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04641-0. PMID 35477758. S2CID 248416916.

- ^ Senturk, Emir; Manfredi, James J. (2013). "p53 and Cell Cycle Effects After DNA Damage". P53 Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.). Vol. 962. pp. 49–61. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-236-0_4. ISBN 978-1-62703-235-3. ISSN 1064-3745. PMC 4712920. PMID 23150436.

- ^ Ding, Lei; Cao, Jiaqi; Lin, Wen; Chen, Hongjian; Xiong, Xianhui; Ao, Hongshun; Yu, Min; Lin, Jie; Cui, Qinghua (2020-03-13). "The Roles of Cyclin-Dependent Kinases in Cell-Cycle Progression and Therapeutic Strategies in Human Breast Cancer". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (6): 1960. doi:10.3390/ijms21061960. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 7139603. PMID 32183020.

- ^ Williams, Ashley B.; Schumacher, Björn (2016). "p53 in the DNA-Damage-Repair Process". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 6 (5) a026070. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a026070. ISSN 2157-1422. PMC 4852800. PMID 27048304.

- ^ Engeland, Kurt (2022). "Cell cycle regulation: p53-p21-RB signaling". Cell Death & Differentiation. 29 (5): 946–960. doi:10.1038/s41418-022-00988-z. ISSN 1476-5403. PMC 9090780. PMID 35361964.

- ^ Ruvolo, P. P.; Deng, X.; May, W. S. (2001). "Phosphorylation of Bcl2 and regulation of apoptosis". Leukemia. 15 (4): 515–522. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2402090. ISSN 1476-5551. PMID 11368354. S2CID 2079715.

- ^ Jabbour, A. M.; Heraud, J. E.; Daunt, C. P.; Kaufmann, T.; Sandow, J.; O'Reilly, L. A.; Callus, B. A.; Lopez, A.; Strasser, A.; Vaux, D. L.; Ekert, P. G. (2009). "Puma indirectly activates Bax to cause apoptosis in the absence of Bid or Bim". Cell Death & Differentiation. 16 (4): 555–563. doi:10.1038/cdd.2008.179. ISSN 1476-5403. PMID 19079139.

- ^ Jiang H, Schiffer E, Song Z, Wang J, Zürbig P, Thedieck K, et al. (August 2008). "Proteins induced by telomere dysfunction and DNA damage represent biomarkers of human aging and disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (32): 11299–304. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511299J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801457105. PMC 2516278. PMID 18695223.

- ^ Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O'Brien E, Sivatchenko A, Kerber RA (February 2003). "Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older". Lancet. 361 (9355): 393–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12384-7. PMID 12573379. S2CID 38437955.

- ^ Jafri MA, Ansari SA, Alqahtani MH, Shay JW (June 2016). "Roles of telomeres and telomerase in cancer, and advances in telomerase-targeted therapies". Genome Medicine. 8 (1) 69. doi:10.1186/s13073-016-0324-x. PMC 4915101. PMID 27323951.

- ^ Charles F. B. de Mirbel, 1813

- ^ Pierre J. F. Turpin, 1825

- ^ Matthias Jacob Schleiden, 1838

- ^ Theodor Schwann, 1839

- ^ B. C. Dumortier: Recherches sur la structure comparée et le développement des animaux et des végétaux. Bruxelles 1832.

- ^ Hugo von Mohl: Ueber die Vermehrung der Pflanzen-Zellen durch Theilung. Tübingen 1835.

- ^ Franz Julius Ferdinand Meyen: Neues System der Pflanzenphysiologie. Berlin 1838.

- ^ Robert Remak: Bericht über die Leistungen im Gebiete der Physiologie. Hrsg.: Arch. Anat., Physiol. und wiss. Med. 1841.

- ^ Robert Remak: Ueber extracellulare Entstehung thierischer Zellen und über Vermehrung derselben durch Theilung. Hrsg.: Arch. Anat., Physiol. und wiss. Med. 1852.

- ^ Masters BR (2008-12-15). "History of the Optical Microscope in Cell Biology and Medicine". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0003082. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^ ZEISS Microscopy (2013-06-01), Historic time lapse movie by Dr. Kurt Michel, Carl Zeiss Jena (ca. 1943), archived from the original on 2021-11-07, retrieved 2019-04-15

Further reading

[edit]- Morgan HI. (2007). "The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control" London: New Science Press.

- J.M.Turner Fetus into Man (1978, 1989). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-30692-9

- Cell division: binary fission and mitosis

- McDougal, W. Scott, et al. Campbell-Walsh Urology Eleventh Edition Review. Elsevier, 2016.

- The Mitosis and Cell Cycle Control Section from the Landmark Papers in Cell Biology (Gall JG, McIntosh JR, eds.) contains commentaries on and links to seminal research papers on mitosis and cell division. Published online in the Image & Video Library of The American Society for Cell Biology

- The Image & Video Library Archived 2011-06-10 at the Wayback Machine of The American Society for Cell Biology contains many videos showing the cell division.

- The Cell Division of the Cell Image Library

- Images : Calanthe discolor Lindl. – Flavon's Secret Flower Garden

- Tyson's model of cell division and a Description on BioModels Database

- WormWeb.org: Interactive Visualization of the C. elegans Cell Lineage – Visualize the entire set of cell divisions of the nematode C. elegans